Mustafa Serdar Palabıyık

TOBB Economics and Technology University

This article intends to analyze the use of comparative historical analysis (CHA) in the discipline of International Relations (IR). After describing the historical evolution and fundamental premises of CHA, the article continues with the classification of CHA. Then the strengths and weaknesses of the method as well as its utilization by various theories of IR are discussed. The second part of the article deals with the employment of CHA by the author of this article in his own research design, in order to give an idea that how CHA might contribute to a better understanding of the “international”. In doing that, the advantages and disadvantages of the method are revisited in a way to show the contributions provided as well as the difficulties encountered in practice. The article concludes that CHA might contribute to the study of IR by enhancing interdisciplinary approaches and by adding a socio-historical depth to the ‘international’, which helps to overcome historicism and presentism at the same time.

1.Introduction

The nineteenth century positivist turn resulted in a strict departmentalization in social sciences, which led to the emergence of clear-cut but artificial boundaries among various disciplines. Although the discipline of International Relations (IR) was a latecomer considering the establishment of the first IR department in 1919, particularly after the World War II, it attempted to distinguish itself particularly from the disciplines of history and political science. The scholars of IR have claimed that this new discipline would examine ‘the present’ contrary to history and ‘the international’ contrary to political science, which has traditionally dealt with ‘domestic’ politics.[1] Drawing such boundaries by this ‘American social science’[2] was criticized by traditional European schools of IR to a great extent, which have argued that trapping international relations within these artificial boundaries would create an explanatory poverty that neglects historical background and domestic elements of foreign policy making.[3] These schools argued that in order to understand ‘the international’, one should consider not only the domestic factors contributing to foreign policy making but also the historical evolution of the institutions and processes; hence they advocated an inter-disciplinary approach.

A second defect of this new discipline of IR was its perception of the nation-state almost as the sole major actor in the international system. The critiques of IR underlined that the nation-state itself is a construct that should be contextualized in history. Moreover, according to them, there have been other actors at the sub-state and supra-state levels that should be taken into consideration as well.

Comparative historical analysis (CHA) can be perceived as a methodological cure for these two problems of IR namely its ahistoricism and the neglect of actors other than the nation-state. Indeed, CHA is also a criticism against traditional historiography, which has been organized as a ‘national’ field emphasizing the uniqueness of its subjects and explaining their development by presenting an evolutionary narrative of the institutions and processes.[4] Thus CHA attempted to broaden the horizons of IR by historicizing it and of history by undermining its claim to examine what is unique and unrepeatable.

Most basically defined, CHA “is concerned with similarities and differences; in explaining a given phenomenon, it asks which conditions, or factors, were broadly shared, and which were distinctive”.[5] Therefore it attempts to put forward a causal understanding of why certain cases in history have resemblances considering a certain social phenomena, whereas others have differences. Such a comparative account would increase the explanatory power of any analysis, since it allows the researcher to test his/her hypotheses on other cases.

In this introductory article on CHA, I attempt to describe this method briefly in a way to demonstrate its fundamental characteristics in two major parts. In the first part, after historicizing the method itself, in other words, introducing the evolution of CHA to the reader, I define the basic premises and the uses of this method as well as various types of comparative analysis. Then, I analyze the strengths and weaknesses of CHA and focus on the alternative approaches, which have been developed to overcome the shortcomings of this method. Finally, I evaluate the relationship between IR theory and CHA in a way to show how CHA has already been employed by some IR theories to overcome the deficiencies of the dominant realist paradigm. The second part of the article is devoted to my own employment of CHA in three of my recent studies. In this part, I try to show how I use comparative method, how I choose the cases that I compared and the practical difficulties that I encountered during my research.

2. CHA in a Nutshell

2.1. The historical background of CHA

Comparison has always been a significant part of social inquiry, because even the simplest definition of ‘the self’ vis-à-vis ‘the other’ require some degree of comparison. Therefore, it is not surprising that a comparative outlook has always been present in historiography. From Herodote’s dichotomy between the Greeks and the barbarians to the classification of peoples in the writings of al-Tabari, from the comparative analysis of nomadic and settled communities by Ibn Khaldun to Vico’s perception of philosophy of history as a “new science”, comparative understanding of actors, cases and processes have been embedded in classical texts of history.[6] The inclination towards comparative methodology was enhanced with the positivist turn in the nineteenth century, which directed historians to seek for a more systematic understanding of history via employing comparison in their writings.[7] From Georg William Friedrich Hegel to Karl Marx, from Max Weber to Nikolay Danilevsky, all these philosophers and historians referred to comparative analogies to demonstrate the complexity of the social phenomena.[8] In the first decades of the twentieth century, eminent European historians, such as Oswald Spengler, Arnold Toynbee and Fernand Braudel praised the virtues of comparison particularly in enriching the historical analysis and in overcoming the detriments of nationalist histories.[9]

Although comparative accounts have always been present in historiography, it was with the works of the French historian Marc Bloch that CHA emerged more or less as a well-defined method of historical inquiry. His famous article entitled “Pour une histoire comparée des sociétés européennes” (Towards a comparative history of European societies) put forward the basic principles of comparative history, on which historians have built an efficient methodological toolkit.[10] He was inspired by John Stuart Mill’s distinction between ‘the method of agreement’ and ‘the method of difference’; the former underlining “a common cause among cases when the cases share the same outcome and have different scores for all of the independent variables but one”; whereas the latter highlighting “a cause of divergent outcomes among cases […] when all of the independent variables but one are the same.”[11] Based on this distinction, Bloch argued that the historian must first choose cross-cultural themes, recurring patterns, global processes or theoretical propositions that are worthy of studying. Then he/she has to decide on the case studies that best reflect the comparative approach and the hypotheses that are aimed to be proved. For Bloch, the selected societies should share historical connections and cultural commonalities in order to make comparison possible. Moreover, the historian must have an expert knowledge of archival research and a significant “proficiency in languages appropriate for the societies, periods and issues to be explored”.[12]

Bloch’s pioneering studies were followed after the end of the World War II by those of other historians, which also weakened the nationalist/historicist historiography vis-à-vis comparative history. As Steinmetz argues, the post-war scientific turn in social inquiry urged the historians “to adopt a comparative approach patterned on natural science experiments and rooted in positivist philosophies of science”.[13] Even some historians like Rushton Coulborn, perceived the comparative method as one of the most important criteria for a study of history to be scientific. Coulborn once wrote that “[s]ince comparison is the most elementary theoretical process and is thereby distinguished from simple description, this study [in which a comparative method is employed] is a scientific study.”[14] This emphasis on scientificity was epitomized by the foundation of a particular journal on comparative history in 1958, namely Comparative Studies in Society and History, by an American historian, Sylvia L. Thrupp, from the University of Chicago.[15] This journal, published by Cambridge University Press, is still a significant forum for comparative historians.

From the 1980s onwards, a promising as well as challenging period for CHA began. On the one hand, comparative history was very much popularized by the works of Charles Tilly and Theda Skocpol, who initiated a very fruitful collaboration between history and sociology, as well as by the works and long editorship of Raymond Grew over Comparative Studies in Society and History between 1973 and 1997.[16] On the other hand, CHA was strongly criticized by two intellectual movements of the 1980s. First, the “cultural turn” in social sciences criticized comparative history for neglecting cultural peculiarities of cases in the name of comparison and emphasized “the specificity of the local focusing on differentiated functioning of societies and cultures within a relativist setting”.[17] Second, the “post-modern turn” criticized CHA for its extreme emphasis on causality and its embrace of metahistorical categories which had been rejected by postmodernist historians as ‘dangerous fictions’.[18] These criticisms forced the comparative historians to take into account these new trends in history and there emerged novel approaches such as transnational or entangled histories, which attempted to overcome the weaknesses of the comparative approach. Today, CHA is still widely used, although the culturalist and post-modernist critiques also continue to display the approach’s shortcomings.

2.2. Defining CHA and its basic functions

Most simply defined, CHA is the systematic study of two or more historical phenomena to put forward similarities and differences in order to contribute to the description, explanation and interpretation of these phenomena.[19] It is not a single method, but rather a generic name for some methodological approaches of social sciences as well as history, which:

[…] inquires how cultural and social differences and similarities were constructed, institutionalized and represented in the past. It examines comparatively historical experiences, recollections, views of history, master narratives, paths of development and structural patterns, in order to comprehend, understand and explain past and present differences and similarities between different societies and cultures.[20]

However, not all comparative analogies can be considered as comparative history. According to Carl Degler, “it is only when the job of explaining differences is undertaken that comparative history begins”, meaning that the study of the phenomena should be comparative rather than simply using sporadic comparisons in a particular historiography.[21] This emphasis on systematic and scientific study of history brings us to the first significant use of comparative history, namely hypothesis testing. According to William Sewell, the historian should be able to check the hypothesis that he/she designed via the comparative method he/she employed:

If an historian attributes the appearance of phenomenon A in one society to the existence of condition B, he can check this hypothesis by trying to find other societies where A occurs without B or vice versa. If he finds no cases which contradict the hypothesis, his confidence in its validity will increase, the level of his confidence depending upon the number and variety of comparisons made. If he finds contradictory cases, he will either reject the hypothesis outright or reformulate and refine it so as to take into account the contradictory evidence and then subject it again to comparative testing. By such a process of testing, reformulating, and retesting, he will construct explanations which satisfy him as convincing and accurate.[22]

Theda Skocpol and Margaret Somers also argue that the comparative method can be used to engage in macro-causal analysis, which is more quantitative than qualitative. For them, macro-causal analysis resembles statistical analysis, “which manipulates groups of cases to control sources of variation in order to make causal inferences when quantitative data are available about a large number of cases”. Moreover, comparative macro-causal analysis is a type of multivariate analysis with which scholars can validate their causal statements about macro-phenomena.[23]

The comparative historical understanding of the ‘scientific’ differs both from traditional theories of history and from sociology. As Hannes Siegrist writes, comparative history is located somewhere between the generalizing tendencies of sociology and individualizing tendencies of history and cultural studies, which is an important contribution of this approach:

[C]omparative historical science differs from those tendencies in the social and cultural sciences which are primarily aimed at checking universalistic statements and developing universally valid theories indifferent to space and time. Whereas genetically individualizing approaches in historical science focus on detecting and representing the particular and thus frequently nurture a cult of what is unique and special, systematic sociology frequently focuses on identifying institutions and regularities which are independent of space and time. Systematically comparative historical science rather stands between these two poles, examining, theoretically, the tension between the general and the particular, the interdependence of the local and the universal and the relation between identity and hybridity, by means of several comparative cases, using quantifying and qualitative methods.[24]

In addition to hypothesis testing, the second use of comparative history is to discover the uniqueness of different societies via comparison. In other words, in order to understand what is peculiar to a particular culture or society, comparison with other cultures and societies is required. This sounds a bit confusing if not contradictory, because comparative history criticizes nationalist/historicist accounts, which prioritize a particular culture/society and neglects the interactions among different actors; but on the other hand, comparative historians are also aware that it is only through comparison that these peculiarities can be underlined. As Skocpol and Somers write, comparative historians “make use of comparative history to bring out the unique features of each particular case included in their discussions, and to show how these unique features affect the working-out of putatively general social processes”.[25]

The third use of comparative history is formulating further problems for research. By employing CHA, uncharted or under-researched themes can be discovered and analyzed thoroughly. Even historians agree that Marc Bloch himself discovered the enclosure movement in southern France—which had been underestimated by historians before him—via his familiarity with the research on the English enclosure system and through his comparative method.[26]

All in all, comparative historical analysis contributes to the different aspects of a researcher’s work. Heuristically, it allows the researcher to identify problems and questions that would otherwise be very difficult to pose. Descriptively, it helps to apply a clear profile to individual cases. Analytically, it serves to criticize pseudo-explanations and help to test hypotheses. Paradigmatically, it transforms one case into one among many possible cases and leads to de-provincialization of historical observation.[27] As Raymond Grew aptly summarized, “[d]eliberately used, comparison can aid historians at four stages of their work: (1) in asking questions, (2) in identifying historical problems, (3) in designing the appropriate research, and (4) in reaching and testing significant conclusions.”[28]

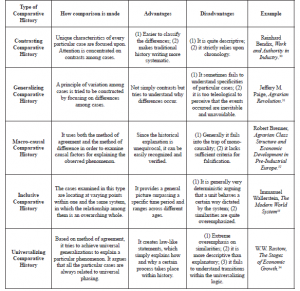

As mentioned above, CHA is not a single method; rather it is a generic name for a variety of methods that have the common characteristic of dealing with different cases via comparing and contrasting them. Based on the works of Skocpol/Somers and Charles Tilly, van den Braembussche classified these methods under five categories. The table below summarizes his classification by focusing on the mode of comparison as well as the advantages and the disadvantages of the method in concern. The examples that van den Braembussche provided are also shown in the table.

Table 1- Classification of CHA[29]

In sum, the categorization of CHA is based on the mode and the aim of comparison. On the one hand, the comparative study might focus either on differences or similarities or both of them; on the other hand, its purpose might be creating a relatively specific comparison between a small number of cases or reaching at grand narratives and universal generalizations by reviewing a large number of cases at a particular period or across different temporal scales. Whatever method is chosen, what is central in CHA is to define the units of comparison and to set the similarities and/or differences among them.

2.3. Strengths and weaknesses of comparative historical analysis

CHA has some promising contributions in designing a systematic and analytic research project. First of all, the comparative method forces the researcher to seek for deeper contextualization, which could prevent him/her from confining himself/herself to dull and simple descriptions. In other words, undertaking such a complex method enhances the analytical premises of the research instead of limiting that research into a descriptive study. Secondly, CHA directs the researcher to underline causal connections among events and processes, and therefore makes him/her avoid strict adherence to story-telling or mere chronological accounts. Third, CHA makes the researcher focus not only on resemblances but also on differences; therefore, it not only leads him/her to refrain from historicism, but also allows him/her to reveal the peculiar conditions resulting in unique responses for some cases.[35] As Friberg [et. al.] argues, CHA compels the historian to engage with at least two separate historiographical traditions and by exposing assumptions about his/her national case to the questions posed by another, it leads to a reexamination of these assumptions, which would ultimately result in undermining the link between history-writing and nation building.[36] Finally, as Michael Adas writes, CHA might be a cure for Eurocentrism, because of the deep immersion of the researcher in diverse and multiple cases.[37]

Besides these advantages, there are several weaknesses of CHA as well. One weakness may be related with the cases chosen. Those, who criticize CHA underscore that the cases chosen by most of the historians employing this method are still more or less territorially-bound; in other words, most of the comparative historical studies tend to compare nation-states. On the one hand, this is not much surprising since the nation-state has been the dominant actor of international relations for at least some centuries. On the other hand, considering CHA’s criticism towards the ahistoricism of a realist understanding of IR, which focuses on the failure to understand the historical evolution of nation-states as actors in the international system and their naturalization as eternal entities, the widespread choice of nation-states as units of comparison seems to be contradictory.[38]

To overcome this weakness, some historians have offered ‘transnational history’ as the solution. Unlike CHA, which is based on the selection of cases to be compared, transnational history seeks to understand the historicization of contacts between communities, polities and societies as a way to understand global trends, instead of digging for specific cases. Therefore, As Glenda Sluga argues, it helps to conceptualize an alternative spatial framework to the nation. She writes that “[h]istories that focus on border regions, historical studies of travel and empire, or of international movements, are all potentially transnational”.[39] Secondly, transnational history might contribute to a focus on actors other than nation-states, including religious communities, regions, civilizations, cities, etc. Finally, transnational history allows the researcher to understand trends, patterns, organizations and individuals, since it has a broader perspective than the comparative approaches.[40]

The second criticism directed against CHA has been a relatively novel approach to historical analysis known as the histoire croisée (entangled history).[41] According to those defending histoire croisée vis-à-vis CHA, the latter has to separate between the units of comparison in order to bring them together under the viewpoints of similarity and difference, which may result in generalizations that might be misleading. Contrarily, instead of categorizing the actors as distinct units, histoire croisée stresses the connections, continuities and hybridities among them; therefore, it rejects distinguishing them clearly.[42] According to Werner and Zimmermann, histoire croisée is not a single theory but an approach “associated with the idea of an unspecified crossing or interaction”.[43] It is a ‘relational’ approach meaning that it examines the links, the transfers and cross-cultural exchanges between various historically constituted formations. It criticizes CHA for its perception of the historian as a detached observer to the cases that he/she examines, which is, according to histoire croisée impossible. It also perceives that CHA suffers from the problem of accepting the actors, institutions or concepts as given and thereby neglecting their historical constitution and evolution. Instead, what histoire croisée offers is diverting from:

[…] one-dimensional perspective that simplifies and homogenizes, in favor of a multidimensional approach that acknowledges plurality and the complex configurations that result from it. Accordingly, entities and objects of research are not merely considered in relation to one another but also through one another, in terms of relationships, interactions, and circulation.[44]

Although comparative historical analysis and histoire croisée were generally perceived as rivals to each other, Kocka and Haupt argue that this is not necessarily the case. According to them, these two approaches may and should feed each other, since without comparison it is difficult to find out the connections and without connections it is difficult to compare and contrast different cases.[45]

All in all, CHA can be considered as a fruitful method allowing interdisciplinary studies among history, sociology, economics, anthropology, etc. Its wide applicability over social phenomena contributes to a deeper contextualization of cases and overcoming historicism. However, at the same time CHA has been criticized for being state-centric and for underestimating the cross-cultural exchanges among cases. These criticisms have given way to the emergence of alternative methods including transnational history and histoire croisée.

2.4. CHA and IR theory

The disciplines of History and IR are so interrelated that it is very difficult to simplify them as history deals with the past and international relations deals with the present. Rather, these two disciplines should be considered as interrelated fields feeding each other. As Thomas Smith argues, when international theory is constructed from the bottom up, history provides the building blocks and when it is built from the top down, history serves to test or falsify theoretical concepts.[46]

The distance between the disciplines of History and IR has generally been represented as if there are dichotomical differences between them. Colin Elman and Miriam F. Elman summarize these dichotomical differences in a way to show how the students of these two disciplines develop prejudices against each other. Accordingly, the first illusionary difference between History and IR is that historians deal with narrative-based explanations, whereas IR scholars deal with theory-based explanations. Secondly, their teleology is assumed to be different; while the historians seek to ‘understand’ the past, the scholars of IR tend to ‘comment’ on the present to ‘predict’ the future. Third, IR scholars criticize the historians for explaining single unique events, while their own works, focusing on classes of events and multiple cases, are claimed to be more explanatory. Finally, it is argued that IR scholars tend to focus on mono-causality for the sake of simplicity by ruling out weaker causal factors, whereas historians accept the plausibility of complex multi-causal explanations underlining different factors leading to a process or event. As Elman and Elman argue, these distinctions, which have been embedded in these two disciplines, are stereotyped fallacies that draw an artificial boundary between them that should be crossed via interdisciplinary approaches.[47]

The dominant paradigm of IR theory, namely realism, has generally been criticized for being ahistorical; in other words, concepts and premises of realist IR theory have been regarded as if they have been always present as they were throughout history. As Smith mentions, “in international relations […] the historical problem is often glossed over or ignored.”[48] He argues that the reason for this neglect is that IR has evolved along positivist lines, which makes the students of this discipline question the validity of the use of historiography.[49] Despite this, some IR theories criticized the ahistoricity problem and argue that history should be brought back into international relations for a better understanding of the contemporary international affairs, structures and processes.

One of the earliest reactions to the ahistorical nature of IR theory came from the English School, which has criticized the behaviouralist methodology dominating the American school of IR, and by extension, the lack of historical depth in the construction of the IR theory.[50] Two studies of the English School are of great significance in terms of employing CHA. The first one is Martin Wight’s Systems of States[51], in which, according to Barry Buzan, he put forward “the theoretical and empirical beginnings of a comparative historical project”. What Wight attempted in this work was constructing “an analytical scheme with a taxonomy of types and then to pursue a comparative analysis via case studies.”[52] The second major work employing a comparative historical method was Adam Watson’s The Evolution of International Society.[53] It is a huge project sketching international societies from ancient Mesopotamian polities to ancient Greek, Roman, Indian and Chinese civilizations, from the Byzantine Empire to the Islamic system and ending with the emergence and evolution of the European international society. The comparative method, although much downgraded in the evolutionary/chronological path of the study, was still visible in Watson’s discussions of various civilizations based on their similarities and differences.

The second major theoretical approach to IR using CHA as a methodological tool, namely historical sociology, is not originally an IR theory. However, John M. Hobson and Stephen Hobden attempted to define a ‘historical sociology of IR’ in order to add a socio-historical dimension to the IR theory that is very much absent in realist understanding.[54] According to Hobson, realism is defected by two forms of ahistoricism, named as chronofetishism and tempocentrism. Chronofetishism is based on “the assumption that the present can adequately be explained only by examining the present (thereby bracketing or ignoring the past)” and it leads to three illusions defined as the reification illusion (making the present appear as a static, self-constituting, autonomous and reified entity), the naturalization illusion (arguing for the emergence of the present spontaneously in line with natural human imperatives), and the immutability illusion (the eternalization of the present in a way to prevent an understanding of change).[55] In order to overcome these illusions, Hobson offered the employment of historical sociology in IR theory in order to (1) reveal the present as a construct embedded in a historical context; (2) denaturalize the present in a way to show that the present is emerged through processes of power, identity and norms; (3) and underline that the present is continuously reconstituted and transformed.[56]

The second form of ahistoricism is tempocentrism, which is described as a “methodology, in which theorists look at history through a ‘chronofetishist lens’”.[57] This methodological concept resulted in a fourth illusion added to the three illusions of chronofetishism, the isomorphic illusion, in which the naturalized and reified present is extrapolated backwards in time to present all historical systems as the same. To overcome this illusion, historical sociology might offer tracing the differences between the past and present international systems, which also require a comparative historical analysis.[58]

In sum, history is an indispensable part of international relations not only in terms of providing data for understanding contemporary world affairs but also in terms of enriching the methodological toolkit for studies of the ‘international’. Through employing methods of history, such as CHA, one can overcome the illusions that emerge out of the chronofetishist and tempocentrist accounts developed by the realist paradigm. Moreover adding historical depth to the ‘contemporary’ can contextualize international relations in a way to provide a better explanatory style.

3. Employing CHA: A Personal Experience

My personal encounter with CHA started when I was writing my dissertation entitled “Travel, Civilization and the East: The Ottoman Travelers’ Perception of the ‘East’ in the Late Ottoman Empire”.[59] In this dissertation, I criticized what is called the ‘Ottoman Orientalism’ and argued that the Ottoman perception of ‘the East’[60] cannot be generalized and simplified in a way to claim that the Ottomans perceived ‘the East’ in an Orientalist fashion as the Westerners had done. In order to substantiate this criticism, I utilized CHA at various levels, in comparing (1) the Western and Ottoman perceptions of civilization as well as ‘the East’; (2) the perception of Ottoman intellectuals, who had never been to ‘the East’, with those of the Ottoman travelers, who had visited parts of ‘the East’; and (3) different perceptions of Ottoman travelers with regard to the region that they had travelled. Indeed, before this decision of employing CHA as my research design, I had not taken any formal methodological education specifically on this particular method. Although in my graduate level IR courses on research methods different methods of social inquiry had been taught, comparative historical analysis was not included in the curriculum, probably because it was perceived as a method of historical inquiry. Therefore, using a comparative method emerged in my mind out of necessity for organizing the geographical, temporal as well as actor-based categories properly. I decided that a comparative approach would not only facilitate criticizing the generalizations and simplifications made by the proponents of the argument of Ottoman Orientalism, but also allow me to clarify my hypotheses and how to tackle them. Therefore, first I noticed and determined the methodological problem and then I chose comparative historical analysis as a method to solve this problem better.

The first level of comparison in my dissertation was on the Ottoman and European conceptualization of civilization. As an ‘Eastern’ people, the Ottomans approached the concept of civilization in an eclectic way by arguing for a synthesis of material elements of ‘Western culture’ and moral elements of ‘Eastern culture’. Such a perception was different from the European perception of civilization, which had generally distinguished between Western civilization and Eastern lack of civilization. Secondly, there are significant differences between the narratives of ‘the East’ by those Ottoman intellectuals who had learned about ‘the East’ from Western resources without actually experiencing any presence there, and the writings of the Ottoman travelers who had visited several parts of ‘the East’. While the former group had more Orientalist credentials, the latter group had perceived ‘the East’ as a space where they also belonged. Finally, a comparative account of Ottoman narratives about different regions of the East, including Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, South/South East Asia, and the Far East demonstrated that for the Ottoman travelers, there was no single and monolithic entity that could be defined as the ‘East’. The Orientalist tone of the travelers might be stronger in some regions than others depending on the personal background of the traveler, the time of travel, and the nature of the region travelled. I noticed during my research that the most Orientalist travelogues were written on Iran, whereas the travelogues on Central Asia had the least Orientalist tone. In sum, CHA allowed me to contextualize the literary genre of travel writing, the conceptualization of civilization and the perception of ‘the East’ in a more explanatory mood by criticizing stereotyping and generalizing attitudes of the advocates of Ottoman Orientalism. Of course, comparative historical analysis is not the sole method that I employed in my dissertation. Indeed I also employed both content analysis for evaluating the secondary sources and discourse analysis for a deeper contextualization of the travelogues. However, it was CHA that I employed the most to ‘construct’ the dissertation; in other words, CHA allowed me to establish a comparative structure to show the similarities and differences between the categories that I had already constructed by utilizing this very method.

Following my dissertation, my research agenda has split into two methodologically. The first track I studied, namely the Ottoman perception of international law, required not a comparative but an entangled approach, since I was attempting to demonstrate the interactions between the Ottoman Empire and the European state system in a way to shape the Ottoman perception of international law. The histoire croisée approach that I utilized in my two articles on the Ottoman recognition of European international law principles and on the education of international law in the Ottoman higher education facilities focused more on cross-cultural interactions, conceptual and perceptional transfers, exchange of ideas, etc. What I claimed in the first article was that the Ottoman ‘entry’ to the European international law system cannot be confined to the Treaty of Paris (1856); the process of Ottoman recognition of European international law and European recognition of the Ottoman Empire as a part of the European state system had occurred much earlier, even as early as the late seventeenth century.[61] The second article, on the other hand, focused on Ottoman intellectuals’ interest in international law starting from the early nineteenth century onwards. It analyzed how the ideas of European international law infiltrated into the Ottoman intellectual circles, first through translations and then via the manuscripts written by Ottoman bureaucrats, who later became scholars of international law in the emerging imperial higher education institutions.[62] These two articles underlined the transfer of concepts and ideas instead of their comparative analysis.

The second track of my research agenda, in which I utilized CHA, includes three recent articles published in various books and journals. The first article entitled “Comparative Narratives of “Catastrophe”: Ottoman Perception of the Balkan Wars and Greek Perception of the Asia Minor Campaign” once again allowed me to engage in an interdisciplinary endeavor, in which I benefitted from the conceptual/methodological toolkit of the disciplines of history, anthropology, literature and international relations.[63] This article emerged out of my interest in the memoirs of statesmen and soldiers written before, during and after World War I. When I was reading the memoirs of Ottoman and Greek statesmen/soldiers, I noticed that there are significant similarities between their narratives. What I needed was a concept that could be utilized to compare and contrast similar historical processes experienced by the Ottoman Empire and Greece in that particular time period. The concept I borrowed from anthropology was ‘catastrophe’, since there are some incidents in Ottoman and Greek histories defined as catastrophe, namely the Balkan Wars described in the literature as ‘the great catastrophe’ (büyük felaket in Turkish) and the Asia Minor campaign of the Greek Army between 1919 and 1922 defined as the ‘Asia Minor catastrophe’ (Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή in Greek). Then I focused on how this concept was utilized by the authors of these memoirs and how the divine and man-made reasons for these two catastrophes were narrated. The similarities that I have found were quite conspicuous, because despite religious differences, some Ottoman and Greek accounts defined similar divine reasons (punishment by God and fate) for the emergence of these catastrophes. The man-made reasons (inability of commanders, political division of the army, lack of preparation, etc.) described particularly by soldier accounts, were also more or less the same. Therefore, the comparative method I employed demonstrated that regardless of political, religious or ethnic differences, the statesmen/soldiers’ narratives of catastrophe were very much similar considering the Ottoman and Greek cases.

In the second article for which I utilized CHA, I returned to the concept of civilization. This time, I decided to compare and contrast the Ottoman and Japanese conceptualization of civilization in the late nineteenth century.[64] Indeed, these two cases were very distant not only concerning the geographical distance that resulted in different modes of relationship with the West, but also with regard to political, social and cultural differences. Therefore, I had some doubts whether there were similarities with regard to the concept of civilization. The starting point of my research was Selçuk Esenbel’s and Rene Worringer’s books[65], in which the Ottoman and Japanese modernization processes were compared. From these I became convinced that these two cases could be compared via the conceptual tool I employed, namely the concept of civilization. The reason I chose this concept was that while writing my dissertation I had already reviewed the literature on civilization as well as the literature on Ottoman-Japanese relations and the Ottoman travelers’ accounts on Japan. On top of this, I wanted to test whether there were similarities and differences between Ottoman and Japanese perceptions of civilization and to what extent these similarities and differences resulted in different outcomes in the Ottoman Empire and Japan. When I compared the Ottoman and Japanese perceptions of civilization, I found out that this concept was perceived as an ideal by the Ottoman and Japanese intellectuals and it was thought that without achieving that ideal, it would be impossible to survive the European encroachment. Both empires suffered from unequal treaty systems and they were aware that unless they adopted the European civilization, they could not get rid of the capitulations imposed by the European powers. Therefore, the issue was not whether Ottoman and Japanese civilizations should be civilized, the intellectuals had already accepted that importing European civilization was inevitable. The question was to what extent the European civilization should be imported. In answering this question, the Westernist intellectuals in these two empires argued for total adoption of the European civilization, whereas most of the conservative intellectuals opted for a partial adoption synthesizing material/technological elements of the European civilization and moral elements of Islamic/Confucian tradition. Although the Westernist and conservative intellectuals had diverse opinions, the general tendency that was adopted by the state was the conservative understanding. This comparative study showed that despite different political, historical and religious backgrounds, when being encountered with a similar threat, the responses developed by Ottoman and Japanese intellectuals were similar, because both of them employed Western concepts to resist against European penetration such as civilization and international law. However, despite the similar conceptualization of civilization, the Ottoman and Japanese Empires followed a very divergent path. While the perception of civilization acquired a more total adoptionist tone via incorporation of Turkish nationalism with the establishment of the Turkish Republic in the Turkish case, in the Japanese case the perception of civilization led to an imperialist expansionism with the pretext of bringing civilization to the un-civilized regions of East Asia.

The most recent article in which I employed CHA was a kind of synthesis of the literature that I produced since my dissertation. It not only combined travel literature and the search by non-European societies for being part of the European state system via the concepts of civilization and international law, but also added another conceptual tool, namely ‘the fraternity of monarchs’, to demonstrate how different non-European monarchs responded similarly to European colonial penetration attempts. In this article, entitled “The Sultan, the Shah and the King in Europe: The Practice of Ottoman, Persian and Siamese Royal Travel and Travel Writing”, I examined the travels of Sultan Abdülaziz of the Ottoman Empire, Shah Nasser al-Din of Iran, and King Chulalongkorn of Siam towards Europe undertaken in the second half of the nineteenth century.[66] These travels were compared and contrasted both in terms of the motives and practice of travel and in terms of the travelogues that emerged out of them. The result was that these travels fulfilled three significant purposes: political; educational; and representational. These travels not only allowed the Ottoman, Persian and Siamese monarchs to engage in alliance formation vis-à-vis their rivals and enemies politically but also contributed to their perception of European civilization in general and the European countries that they visited in particular, thus serving an educational purpose. However, the most significant outcome of these travels was representational, formulated with the concept of the ‘fraternity of monarchs’.[67] These Eastern monarchs perceived themselves and made the European monarchs perceive them as equally sovereign. This was a very significant achievement not only blurring the artificial boundary between the East and the West, but also contributing to the preservation of sovereignty of their respective states.

Considering all these experiences, I can speak to both advantages and practical difficulties encountered while making these researches. The first advantage is that CHA allows me to open up new questions in relatively under-researched fields of Ottoman political and diplomatic history. Rather than simply narrating or explaining a particular process or event, through CHA the Ottoman case can be contextualized within a broader spectrum via comparison with neighboring or distant countries. This brings us to the second advantage; through CHA, I have been able to avoid historicist accounts that make the Ottoman Empire a specific case without locating it in the European, Middle Eastern or Asian regional systems. Ottoman political/diplomatic history cannot be understood properly if such a comparative approach is not employed. Finally, CHA was useful for testing the hypotheses of my research. My claims of similarity between the Ottoman and Greek approaches towards the reasons for national catastrophes, between the Ottoman and Japanese approaches towards the concept of civilization, and between the Ottoman, Persian and Siamese approaches towards royal travel and travel writing, could to a great extent be tested by CHA. Moreover, the use of conceptual tools to link these cases was a novel approach; instead of simply comparing and contrasting the cases, the concepts such as catastrophe, civilization or fraternity of monarchs served well for demonstrating that even distant units might have developed similar conceptual understandings when exposed to similar conditions.

Besides these advantages there are several practical problems that should be resolved during such comparative studies. One such problem is choosing the units of analysis. In all my comparative studies, I choose units from different political entities; in other words, I did not employ CHA for comparing units under the same political entity. However, the units I chose for comparing were not nation-states; rather politicians/soldiers, intellectuals or monarchs. Since these units are not monolithic a degree of generalization is required. Here the balance between making generalizations and focusing on the peculiarities is very important. If one considers the peculiarities too much, then comparison might not be possible. On the other hand, if one makes too many generalizations for the sake of comparison, crucial peculiarities might be neglected. The second practical problem is the difficulty of managing a vast literature. The more cases one chooses, the more languages he/she has to command to search for the literature, if there is not enough translations or secondary literature to make accurate comparison. In my case, I have no knowledge of Greek, Japanese, Persian or Siamese languages; however, there was a vast secondary literature in European languages. Moreover, a sufficient amount of the state documents, memoirs of statesmen, or the writings of the intellectuals on the questions I was asking and hypotheses I was attempting to test had been translated into European languages that I can master. Of course, the ‘sufficient amount’ depends of the capability of putting forward a substantiatable argument, and this requires a careful selection of the literature. Since comparative studies have a tendency to generalize in order to find out matters of comparison, not all peculiarities can be dealt with; therefore, the literature must be analyzed and chosen in a way to substantiate the arguments in concern.

4. Conclusion

CHA is a promising methodological tool for students of IR for several reasons. First of all, it allows a great deal of interdisciplinarity, which is essential in the discipline of IR. With CHA, disciplines like history, political science, sociology, anthropology, literature, etc. can be collaborated with to broaden the horizons of international relations. Secondly, CHA can reconciliate between the qualitative vs. quantitative methods debate in IR. As discussed above, despite its qualitative background CHA employs also datasets, statistical methods and even multi-variate analysis. Therefore, those who are searching for an inter- or multi-methodological approach, may also utilize CHA for testing their hypotheses. Third, CHA helps to overcome the ahistoricist deficiencies of the realist paradigm by adding a socio-historical dimension. It not only eliminates the presentist accounts that perceive current actors and structures of international relations as eternally given, but also cures the problems that emerge out of state-centrism by adding sub- and supra-state actors as units of comparison.

Despite these advantages, researchers should also be careful about some sensitive aspects with regard to CHA. To start with, if not used properly, the method might be so eclectic as to lead to a lack of a clear method in a particular study. In other words, researchers should use CHA not simply for making comparative analogies; rather they should employ the method systematically to test their hypotheses. Secondly, CHA requires a sufficient command of the languages of the literatures in concern as well as the knowledge of how to make proper archival studies. Both primary and secondary resources, written and published in the languages required to make comparative studies, are essential. This means a tiresome research project compared to many of the other methods of social science. Third, the researcher should take into consideration the degree of generalization and specification. The balance between these two is very important in making comparative studies. A comparison should be specific enough to enlighten the peculiarities of the cases in concern and general enough to make comparison possible.

Students of international relations have the tendency to see history as irrelevant to understanding contemporary world affairs, whereas students of history perceive international relations as being outside the focus of their own research agenda, since IR, according to them, deals with the present. This reciprocal prejudice and illusion impoverishes both disciplines. Therefore, CHA might undermine these illusionary prejudices by creating an interdisciplinary toolkit that can allow the students of both disciplines to widen the fields of research as well as to strengthen their explanatory capacity. The outcome of this interdisciplinary approach is a historicized international relations and an internationalized history, which makes the studies of both disciplines better-formulated and well-contextualized.

Mustafa Serdar Palabıyık, Assoc. Prof., TOBB Economics and Technology University, Department of History. Email: spalabiyik@etu.edu.tr.

Adas, Michael. “Comparative History and Challenge of the Grand Narrative.” In A Companion to World History, edited by Douglas Northrop, 229–43. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2012.

Aston, T. H., and C. H. E. Philpin, ed. The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Baldwin, Peter. “Comparing and Generalizing: Why All History is Comparative, Yet No History Is Sociology.” In Comparison and History: Europe in Cross-National Perspective, edited by Deborah Cohen and Maura O’Connor, 1–22. New York and London: Routledge, 2004.

Bendix, Reinhard. Work and Authority in Industry: Managerial Ideologies in the Course of Industrialization. New York: Transaction Publishers, 1963.

Bloch, Marc. “Pour une histoire compare des sociétés européennes.” Revue de synthèse historique 46 (1928): 15–50.

Brenner, Robert. “Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe.” Past and Present 70 (1976): 30–75.

Buzan, Barry. An Introduction to the English School of International Relations: The Societal Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014.

Cohen, Deborah, and Maura O’Connor. “Introduction: Comparative History, Cross-National History, Transnational History – Definitions.” In Comparison and History: Europe in Cross-National Perspective, edited by Deborah Cohen and Maura O’Connor, ix–xxiv. New York and London: Routledge, 2004.

Coulborn, Rushton. “A Paradigm for Comparative History?” Current Anthropology 10, no. 2–3 (1969): 175–78.

Degler, Carl N. “Comparative History: An Essay Review.” The Journal of Southern History 34, no. 3 (1968): 425–30.

Dunne, Tim. “A British School of International Relations.” In The British Study of Politics in the Twentieth Century, edited by Jack Hayward, Brian Berry, and Archie Brown, 395–424. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Elman, Colin, and Miriam Fendius Elman. “Diplomatic History and International Relations Theory: Respecting Difference and Crossing Boundaries.” International Security 22, no. 1 (1997): 5–21.

Esenbel, Selçuk. Japon Modernleşmesi ve Osmanlı: Japonya’nın Türk Dünyası ve İslam Politikaları. 2nd ed. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2015.

Gills, B. K. “International Relations Theory and the Processes of World History: Three Approaches.” In The Study of International Relations: The State of the Art, edited by Hugh C. Dyer and Leon Mangasarian, 103–54. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989.

Grew, Raymond. “The Case for Comparing Histories.” The American Historical Review 85, no. 4 (1980): 763–78.

Friberg, Katarina, Mary Hilson, and Natasha Vall. “Reflections on Trans-national Comparative History from an Anglo-Swedish Perspective.” Historisk Tidskrift 127, no. 4 (2007): 717–37.

Hobson, John M. “What’s at Stake in ‘Bringing Historical Sociology Back into International Relations’? Transcending ‘Chronofetishism’ and ‘Tempocentrism’ in International Relations.” In Historical Sociology of International Relations, edited by Stephen Hobden and John M. Hobson, 3–41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Hobden, Stephen, and John M. Hobson, ed. Historical Sociology of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3, Discoveries and Interpretations: Studies in Contemporary Scholarship, Volume I (1977): 41–60.

Iriye, Akira. Global and Transnational History: The Past, Present and Future. London and New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2013.

Kocka, Jürgen and Heinz-Gerhard Haupt. “Comparison and Beyond: Traditions, Scope and Perspectives of Comparative History.” In Transnational History: Central European Approaches and New Perspectives, edited by Heinz-Gerhard Haupt and Jürgen Kocka, 1–32. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009.

Lange, Matthew. Comparative-Historical Methods. London: Sage, 2013.

Levine, Philippa. “Is Comparative History Possible?” History and Theory 53 (2014): 331–47.

Mahoney, James, and Dietrich Rueschemeyer. “Comparative Historical Analysis: Achievements and Agendas.” In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer, 3–38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Paige, Jeffery M. Agrarian Revolution: Social Movements and Export Agriculture in the Underdeveloped World. New York: Free Press, 1975.

Palabıyık, Mustafa Serdar. “Comparative Narratives of ‘Catastrophe’: Ottoman Perception of Balkan Wars and Greek Perception of Asia Minor Campaign.” In 100. Yılında Balkan Savaşları (1912–1913): İhtilaflı Duruşlar, Vol. I, edited by Mustafa Türkeş, 477–92. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, 2014.

———. “The Emergence of the Idea of 'International Law' in the Ottoman Empire before the Treaty of Paris (1856).” Middle Eastern Studies 50, no. 2 (2014): 233–51.

———. “İngiliz Okulu.” In Uluslararası İlişkiler Teorileri, edited by Ramazan Gözen, 217–56. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2014.

———. “International Law for Survival: Teaching International Law in the Late Ottoman Empire (1859–1922).” Bulletin of School of Oriental and African Studies 78, no. 2 (2015): 271–92.

———. “Osmanlı ve Japon Entelektüellerinin Modernleşme ve Medeniyet Algılarının Mukayesesi.” In Ortadoğu Barışı İçin Türk-Japon İşbirliği, edited by Masanori Naito, İdiris Danışmaz, Bahadır Pehlivantürk, M. Serdar Palabıyık, 3–18. Kyoto: Doshisha University Press, 2015.

———. “The Sultan, the Shah and the King in Europe: The Practice of Ottoman, Persian and Siamese Royal Travel and Travel Writing.” Journal of Asian History 50, no. 2 (2016): 201–34.

———. “Travel, Civilization and the East: The Ottoman Travellers’ Perception of the “East” in the Late Ottoman Empire.” PhD diss., Middle East Technical University, 2010.

Paulmann, Johannes. “Searching for a ‘Royal International’: The Mechanics of Monarchical Relations in Nineteenth Century Europe.” In The Mechanics of Internationalism: Culture, Society and Politics from the 1840s to the First World War, edited by Martin H. Geyer and Johannes Paulmann, 145–76. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Rosenthal, Franz. A History of Muslim Historiography. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1952.

Rostow, W.W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960.

Saunier, Pierre-Yves. Transnational History. London and New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2013.

Sewell, Jr., William H. “Marc Bloch and the Logic of Comparative History.” History and Theory 6, no. 2 (1967): 208–18.

Siegrist, Hannes. “Comparative History of Cultures and Societies: From Cross-Societal Analysis to the Study of Intercultural Interdependencies.” In “Comparative Methodologies in the Social Sciences: Cross-Disciplinary Inspirations.” Special issue, Comparative Education 42, no. 3 (2006): 377–404.

Sluga, Glenda. “The Nation and the Comparative Imagination.” In Comparison and History: Europe in Cross-National Perspective, edited by Deborah Cohen and Maura O’Connor, 103–14. New York and London: Routledge, 2004.

Smith, Thomas W. History and International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Steinmetz, George. “Comparative History and Its Critics: A Genealogy and a Possible Solution.” In A Companion to Global Historical Thought, edited by Prasenjit Duara, Viren Murthy and Andrew Sartori, 412–36. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Skocpol, Theda. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Skocpol, Theda, and Margaret Somers. “The Uses of Comparative History in Macrosocial Inquiry.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 22, no. 2 (1980): 174–97.

Tilly, Charles. As Sociology Meets History: Studies in Social Discontinuity. New York: Academic Press, 1981.

———. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York: Sage, 1984.

Van Den Braembussche, A. A. “Historical Explanation and Comparative Method: Towards a Theory of the History of Society.” History and Theory 28, no. 1 (1989): 1–24.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System, Vol. I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press, 1974.

———. The Modern World-System, Vol. II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. New York: Academic Press, 1980.

———. The Modern World-System, Vol. III: The Second Great Expansion of the Capitalist World-Economy, 1730–1840s. San Diego: Academic Press, 1989.

———. The Modern World-System, Vol. IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Watson, Adam. The Evolution of International Society. London: Routledge, 1992.

Werner, Michael, and Bénédicte Zimmermann. “Beyond Comparison: Histoire Croisée and CHAllenge of Reflexivity.” History and Theory 45 (2006): 30–50.

Wight, Martin. Systems of States. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1977.

Williams, Andrew J., Amelia Hadfield, and J. Simon Rofe. International History and International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

Worringer, Renée. Ottomans Imagining Japan: East, Middle East and Non-Western Modernity at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan, Transnational History Series, 2014.