1.Introduction

Foreign aid has been among the “real innovations which the modern age has introduced into the practice of foreign policy,” according to Hans Morgenthau. This innovation in the developing world constitutes a large claim on government budgets. For many, foreign aid constitutes a significant part, on average ten percent, of the average recipient’s national income. With this amount, aid has been used as an interesting tool of change in recipient countries. It is also a focal point of debate and an issue of contention in academic and policy circles alike. Preoccupied with foreign aid’s effect on economic growth, democratization, civil war and many other areas, economists and political scientists have paid much less attention to other potentially important dimensions of aid’s effect on recipient countries, particularly its effect on interstate conflicts.

Foreign aid, unlike other explanatory parameters of interstate conflict, is a highly flexible tool for policy making. This flexibility in character may do as much harm as good to recipient countries, as it creates a higher level of responsibility for policy makers, as well as a need for a broad understanding of whether, where, and how foreign aid is effective in promoting peace or war among recipient countries. Moreover, many studies in various research programs within political science and economics have suggested the use of aid to improve conditions related to their variables of interest without paying specific attention to how aid intake in itself changes the value of other important variables. This study criticizes this frictionless conception of foreign aid and analyzes how aid receipt induces a change in various domestic actors’ behaviors, which in turn translates into foreign policy outcomes.

To date, only a few studies analyze foreign aid’s effect on interstate conflicts, and they focus on how foreign aid affects a recipient’s conflict behavior toward a donor. The link between aid and interstate peace among recipient countries receives almost no attention, save for some mention by area specialists, and has not been analyzed through large-N analysis. Moreover, although previous analyses stress a supply-specific effect of aid on interstate peace and employ donor motives as a main driving force of peace, how foreign aid enters into the state machine and produces foreign policy outcomes for recipient countries with differing domestic structures is not well known. In addition, an extensive literature developed in recent years indicates foreign aid’s tenure-prolonging effect for recipient governments.

The impact of foreign aid on domestic power balances, hence, requires going beyond a supply-specific approach, and calling for a second-image explanation of how varying domestic factors condition the use of aid, which in turn affects leaders’ decisions during crisis bargaining. It is the intent of this study to fill this identified gap in the literature. In doing so, this paper juxtaposes the domestic politics and foreign policy nexus by interweaving insights from various areas of comparative politics, international security, and international political economy.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: The next section reviews previous research on the politics of effective aid. Section 3 develops the theoretical model. Section 4 constructs the procedures for creating a suitable setting for testing the proposed theory. Section 5 presents the results of the empirical enquiry. The concluding section focuses on the broader implications of the study.

2. Politics as a Friction on Aid Effectiveness

Since Griffin and Enos’ influential analysis of how aid affects growth in receiving countries, a large literature has developed over whether, how, and why aid affects various economic phenomena such as growth, quality of life, inequality, and poverty in target countries. Since then, aid effectiveness has been an issue of contention among scholars, and the literature has been divided into two broad camps: aid optimists and aid pessimists. Griffin and Enos’ findings of a negative bivariate correlation between foreign aid and growth were later overturned by Gulati, who finds a significant positive relationship with a better sample (almost doubling the size of country coverage). Boone’s highly influential study raises the bar both by increasing country coverage to 96, and year coverage to 21 (1971-1990), as well as accounting for the effect of aid in countries with different political regime types, and finds a null effect of aid on investment and growth. Since then, responses (what we today call aid effectiveness literature) to Boone’s influential work constitute two main strands: an orthodox economic approach, which analyzes aid-growth nexus, and a politics approach, which conditions effectiveness to the compatible interests of domestic political actors. In the first strand, scholars utilize/develop cutting-edge econometric models, generating new data to show aid has a positive, null, or negative effect on the well-being of people in recipient countries. The politics approach focuses on incentives facing the key decision makers in recipient countries and assesses aid effectiveness using various important dependent variables such as economic growth, quality of life, poverty alleviation, and inequality reduction. Although this literature does not address foreign aid’s effect on interstate war, it has insights on how aid directly and indirectly affects political leaders’ incentives, which in turn, affect the conflict behavior of recipient countries. Previous research within this literature finds that aid effectiveness in promoting economic growth, poverty alleviation, and quality of life in recipient countries is conditional on the presence of democratic institutions; whereas in autocratic countries, aid is highly fungible and used for economically non-productive goals.

Building on Boone’s analysis and correcting errors in his model specification, Svensson argues that the effect of aid on economic growth depends on the accountability of government policies. In a conceptual model, he shows that governments’ incentives are shaped by the degree of political accountability in a polity. Where governments are accountable to their voters, they risk defeat if they divert aid resources to policies that are valuable to the government but not to voters. As accountability increases, governments must use aid resources for productive public investment in order to remain in office. In the alternative scenario, where accountability is low, governments’ optimal strategy is to divert resources to areas that only benefit its members. The results of empirical analyses show that as a regime becomes more democratic, aid has an increasingly positive impact on growth. Similarly, Kosack finds that aid is effective and significantly increases quality of life in democracies; whereas it is ineffective and potentially harmful in autocracies. Kosack argues that the tendency of democratic governments to meet the popular demands of their constituents will have no discernible effect on quality of life if the country is poor and not receiving foreign aid. If a democratic government has sufficient resources, its investments in quality of life will translate into better living standards for voters. In contrast, for autocracies, aid is ineffective in enhancing quality of life and may even have an adverse effect. Isham et al. find that World Bank-financed government investment projects are more likely to be effective in countries with strong civil liberties. They argue that the freedom of dissent and criticism and citizens’ ability to organize protests facilitate greater citizen voice and hence more-effective government policies. Bjella shows aid effectiveness with a different dependent variable: poverty alleviation. She notes that not only accountability, but also political inclusiveness affects whether aid is used as a means to improve living conditions within the recipient countries. Building on the selectorate theory, Bjella shows that aid is more effective in democracies than in autocracies because the leaders of the former rely predominantly on the provision of public goods to remain in office, which necessitates the use of aid money for poverty alleviation; whereas leaders of the latter seek to distribute private goods to key supporters in order to remain in office. However, whether aid is effective or fungible has important implications on how leaders make foreign policy, which I elaborate in the next section.

3.Aid Effectiveness as a Friction in Crisis Bargaining

War is costly and risky; yet, it recurs. Given its costs and risks, rational actors should be able to locate a negotiated settlement preferable to the gamble of war. As long as there are costs to fighting, war is ex-post inefficient because parties in a dispute could be better off if they achieve the same outcome through negotiation. Fearon, however, shows that rational leaders may not be able to reach a mutually preferable negotiated settlement due to private information about relative capabilities or resolve as well as the parties’ incentives to misrepresent this information. This means that leaders know their own resolve and their capabilities but are uncertain about their opponent’s willingness to fight and their capabilities.

Given this uncertainty, both parties have incentives to misrepresent their capabilities and resolve to get a better deal on the table; that is, they may exaggerate their true willingness or capability to fight and hide their vulnerabilities. These incentives create disagreements about parties’ relative capabilities. Hence, states face a dilemma: Normal forms of diplomatic communication will prove useless to reach a mutually preferable bargaining outcome because these methods do not lift the uncertainty about parties’ true preferences. Schelling suggests that the central way leaders address this dilemma is by making their threats credible through costly signals. He summarizes the essence of costly signaling as the “irreversible sacrifice of freedom of choice,” in other words, the power to communicate informative signals to an opponent depends on one’s ability to issue a threat that carries high costs for failure to follow through. That is, backing down from a previous threat that meets resistance is associated with a cost at least as large as the cost of war for the issuing party. As a result, a more credible signal brings better information, which in turn increases the likelihood that the dispute is resolved on the table rather than in a battle.

The audience-cost theory suggests that leaders in democratic regimes can send informative signals and allow their opponents to learn their resolve by making public threats in international crises. They do so by tying their own hands through public threats, which makes backing down a costly option because of the domestic audience’s ability to punish leaders who are caught bluffing. As a result, the domestic political structure influences leaders’ abilities to signal their willingness to fight and to make credible threats against their opponents by putting their own tenure at stake. This situation leads to the substantial conclusion that democracies can signal their willingness to fight to other states more credibly than authoritarian states can, which explains the separate peace we observe between democracies.

In Fearon’s model, audience costs are exogenous and they can take any mechanism that may increase the domestic political cost of retreat once a challenge is issued, because failure to follow through on a threat gives the opposition an opportunity to deplore the international loss of credibility, face, or honor. However, the fact that leaders misrepresent their resolve and issue a challenge they may not follow through on is done to derive greater benefit on behalf of the domestic audience; a successful bluff means higher benefits for the audience as a whole. As a result, there is no rational incentive for the audience to punish; hence, the threat issued by those leaders should not separate them from unresolved types. In turn, a peaceful solution cannot be the equilibrium. So the question turns to reasons for the audience to punish leaders caught bluffing. Why should backing down result in punishment? Smith suggests that citizens want to retain competent leaders and thus remove incompetent ones. The domestic audience uses crisis bargaining outcomes as a signal of the leader’s competence, and since following through on a threat is less costly for a competent leader, those who do not carry out their threats signal incompetence. This main conclusion, however, is not without a caveat. Leaders with high ex-ante probability of re-election will have difficulty generating audience costs. Hence, citizens’ positive bias toward a leader decreases her ability to tie hands, and thus, diminishes her ability to send costly signals to opponents.

Juxtaposing these insights with those in the aid effectiveness literature allows us to address how foreign aid shapes the incentives facing leaders in the domestic arena and how this situation leads to changes in outcomes during crisis bargaining. Aid scholars show that aid effectiveness in promoting economic growth, poverty alleviation, and quality of life in recipient countries is conditional on the presence of democratic institutions. These findings in the aid effectiveness literature have important implications for audience cost and democratic peace. Foreign aid effectiveness sends strong signals about a leader’s competence in improving citizen welfare, hence, increases her ex-ante chances of re-election. This creates problems for foreign policy in general and interstate crises in particular: As citizens’ perception of their government’s competence increases in areas other than the current dispute during peace years, the government continues to stay in power until this surplus increase in the competence of the leader is undone through serious foreign policy failures. As a result, given the surplus increase in ex-ante re-election probabilities, aid-recipient democratic governments will have difficulty generating credible threats. As a result, as the amount of aid increases, the ability of leaders in democratic regimes to send informative signals is likely to decrease, hence, foreign aid is likely to retard leaders’ ability to commit themselves to following through on previous threats.

Hypothesis 1: Foreign aid decreases the ability of democratic regimes to generate audience costs.

Hence, when a state is targeted by a democratic initiator, we should observe that the targeted state will be less likely to resist that challenge compared to a challenge issued by a non- democratic state. As the amount of aid to the initiator increases, the targeted state should not be less likely to resist a challenge issued by a democratic initiator. The main implication of this deduction is profound: As aid flows increase, democracies lose the informational advantage, which audience-cost theorists argue is responsible for democratic peace.

Hypothesis 2: Foreign-aid-recipient democracies are not significantly more peaceful to each other.

In the next section, I explain the procedures for a test of these two hypotheses on audience costs and interstate conflict onset.

4. Research Design

4.1. Audience cost

Given that the first hypothesis focuses on the role of aid on audience-cost generation, I assess the role of foreign aid on dispute reciprocation through a directed-dyadic level of analysis.

In this setting, the implications of the hypothesis are two-fold: Democratic states face less resistance once they initiate a conflict. However, as aid flows to the democratic initiator increase, we should observe an insignificant relationship between democracy and resistance behavior by the targets. To test this hypothesis, I investigate the impact of foreign aid on targets’ reciprocation propensity for the period 1961 to 2001. Given the hypothesis is related to the potential behavior of a target once it is challenged, I use a sample of cases where an initiator challenged the status quo and I analyze the target’s behavior depending on the regime type of the initiator and the amount of aid it receives. As a result, the dependent variable is whether the target state chooses to resist the initiator’s challenge. Following Schultz, I code the dependent variable as 1 if the target reciprocates a given challenge in kind or escalates the dispute to a fatal battle or full-scale warfare, and as 0 if the target takes no militarized action. The data for reciprocation is acquired from the Correlates of War project.

4.1.1. Foreign aid

Foreign aid is the disbursed amount of net official development assistance and official aid (constant 2009 US$) for each country for any given year, and data is acquired from the World Bank. To avoid biases that may be a result of the list-wise deletion method, I follow several imputation rules: If countries have missing data for the entire period of analysis, I treat these as MNAR (missing not at random) and impute them with a 0, assuming that these countries received no aid for the entire period. Next, I treat the remaining missing data as MCAR (missing completely at random) and interpolate between missing observations. To account for the role of foreign aid in altering the actor’s pay-off from negotiation and conflict, I introduce aid variables in terms of per capita and as a percentage of GDP. For example, we cannot think the same amount of aid has the same impact in a country like Kenya, with a population around USD 40 million and GDP around USD 70 billion, and in a country like Niger, with a population around USD 15 million and GDP around USD 15 billion. The data for population and GDP are acquired from Gleditsch. To account for the potential endogeneity between conflict and foreign aid and the underlying lagged effect of foreign aid on conflict behavior, I incorporate a lag structure in all models. Following the standard employed in other conflict studies, I lag all independent variables by one year.

The reciprocation model includes a variable, Democracy , indicating whether an initiator is democratic or not. I also include a variable, Democracy , indicating whether a target is democratic or not, as well as another variable, Both Democratic, indicating whether both the initiator and the target are democratic or not. The data for regime type comes from the Polity IV dataset, which ranges from -10 to 10; a state is coded as democratic if it achieves a score of 6 or higher in the composite index

4.1.3. Control variables

Following the practices in the literature, I also consider various other factors relating to reciprocation behavior: I create three dummy variables to account for relative military power, Major Power-Major Power, which is coded as 1 if both states in a dyad are major powers; Major Power-Minor Power, which is coded as 1 if the initiator is a major power and the target is not; and Minor Power-Major Power, which is coded as 1 if the initiator is not a major power but the target is. Reciprocation is not meaningful if the initiator cannot reach the target. Thus, I include Distance, measuring inter-capital proximity, and Contiguity, a measure that equals 1 if two states are directly contiguous by land or water. I also account for the presence of an alliance between the initiator and the challenger. Moreover, I control for the nature of the demand made by the initiator; hence, I code whether the demand involves a revision of the territorial status quo, a policy, the target’s regime type or government, or something else. For each revision type, I include four dummy variables: Territory, Policy, Government or Regime, and Other. Data for major power status, distance, contiguity, and revision types are generated by EUGene Software 3.204.

4.2. Interstate peace

Given that the second hypothesis concerns the role of aid inflows on democratic peace, I assess the role of foreign aid on conflict onset at a non-directed dyadic level. Following the implications of Hypothesis 1, the implications of Hypothesis 2 are two-fold. Two democratic states should be peaceful towards one another. However, as aid inflows increase in a given pair, the informational advantage of democratic pairs should disappear; hence, democracy should have an insignificant effect on conflict onset. In order to analyze the implications of the theory on conflict onset, I utilize three measures of conflict onset: the Correlates of War project’s definition of militarized interstate disputes (MIDs), Fatal MIDS (MIDs with at least one battle-related death), and the International Crisis Behavior project’s definition of interstate crisis.

4.2.1. Foreign aid

Similar to the reciprocation analyses, I utilize two operationalizations of foreign aid, Aid Per Capita and Aid/GDP. The non-directed dyadic implications of the hypothesis are, however, different: Consider two democratic states S1 and S2. S1 receives less aid than S2 does. Hence,

the leader of S2 can increase the welfare of her fellow citizens better than the leader of S1. In this case, S1 sends more-informative signals to S2 than S2 to S1 does. The quality of the signal in a given pair decreases as S1 starts to receive more aid, given that S2 still receives more aid than S1. As a result, following the weak-link assumption, aid variables indicate the lowest aid inflows in a given pair: Aid per CapitaL and Aid/GDPL.

4.2.2. Dyadic regime

The models also include DemocracyL, the smaller democracy score in a dyad. The data comes from the Polity IV dataset and the variable ranges from -10 to 10. Larger values of this variable indicate a higher democracy score for both members of a dyad. Moreover, to account for the conflict-inducing effect of regime distance, the model includes Regime Difference, calculated as the absolute value of the difference between the higher and smaller democracy score in a dyad. This operationalization is adopted over the standard higher democracy score in a dyad – DemocracyH – because DemocracyH conflates both the allegedly conflict-dampening impact of joint democracy and the conflict-exacerbating impact of political distance, making it difficult to distinguish between the competing processes. Moreover, DemocracyH implies that if the regime difference is 0, that is, the democracy scores for state A and B are identical, countries will be more conflict prone as they democratize. This implication obviously contradicts the core hypothesis that the more democratic two countries are, the more likely peace exists between them.

4.2.3. Control variables

Capability Ratio, defined as the natural logarithm of weaker states’ capabilities (composed of military, economic, and demographic capabilities by computing each state’s average share of system-wide capability) in relation to the stronger state’s capabilities, is included to account for the distribution of capabilities, as power preponderance deters conflict, while equal distribution increases the risks of conflict. The models also take into account the dramatic growth in the number of sovereign nations since WWII. In addition, a conflict is unthinkable if at least one state cannot reach the other. Thus, I include Distance, measuring inter-capital proximity, and Contiguity, a measure that equals 1 if two states are directly contiguous by land. For the same reason, I add Major Power status, coded as 1 if a dyad includes at least one great power. The data for the Polity IV score, number of states, capability ratio, contiguity, distance, and major power status are generated by EUGene Software 3.204.

5.Results

5.1. Audience cost

The empirical analyses reveal strong evidence that foreign aid reduces leader ability to generate audience costs. As the amount of aid received by a state increases, the disputes it initiates do not systematically differ from those initiated by autocratic states. I begin by examining the rate at which democracies face resistance once they initiate a MID. The Correlates of War dataset records 971 disputes between 1961 and 2001. In 450 of these cases, the targets reciprocated in kind or escalated the dispute to a higher hostility level (46.3% of total cases). In 521 cases, the targets took no recordable action (53.6% of total cases). The democratic advantage becomes visible when we compare the percentage of targets who reciprocated against democratic initiators and the percentage of those who reciprocated against non- democratic initiators. There were 361 democratic initiators and only 36.8% of these initiators faced resistance by their targets. This quantity for non-democracies is 51.9%. As a result, we clearly see that democratic regimes are less likely to face resistance from their targets than non-democratic regimes. However, when we take into account the foreign aid received by

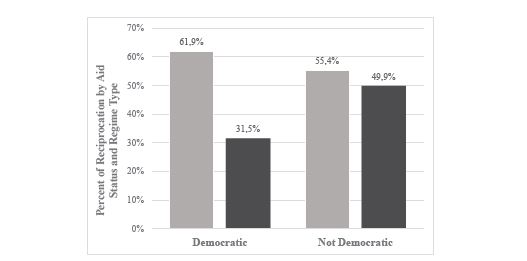

the initiator state, a dramatic pattern surfaces. Figure 1 plots the percentage of reciprocation by distinguishing whether the initiator is democratic or non-democratic and an aid recipient or not an aid recipient based on a cut-off of Aid/GDP being equal to or greater than 1%. The light gray bars show the percentage of reciprocation against aid-recipient initiators and the dark gray bars show the percentage of reciprocation against non-aid-recipient initiators. The difference between non-aid-recipient democracies and the other three categories is evident: Non-aid-recipient democracies faced resistance only in 31.5% of cases, whereas aid-recipient democracies faced resistance from their targets in 61.9% of cases. On the other hand, the difference between non-democracies that received aid and those that did not is not as high: Disputes initiated by aid-recipient non-democracies were reciprocated 55.4% of the time, whereas those initiated by non-aid-recipient democracies were reciprocated at a rate of 49.9%. As we can see, non-aid-recipient democratic initiators are starkly different from the other three categories, whose threats face similar resistance rates by their targets.

Figure 1: Percentage of Dispute Reciprocation by Aid Status and Regime Type

Notes: Light gray indicates reciprocation rates for aid-recipient states in the sample. Dark gray indicates reciprocation rates for non-aid-recipient states.

Controlling for potential confounders is important to partial out the effect of foreign aid on the ability of democracies’ audience-cost generation. For one thing, the observed relationship might be driven by factors that may complicate the causal relationship in a way that the observed relationship has nothing to do with audience-cost generation. As a result, I include various control variables utilized in the audience-cost literature: major power status, distance, contiguity, and alliance between the initiator and the target, as well as the nature of the revision sought by the initiator. I test the hypothesis with multiple regressions. Given that the dependent variable, reciprocation, is dichotomous, I employ a logit model.

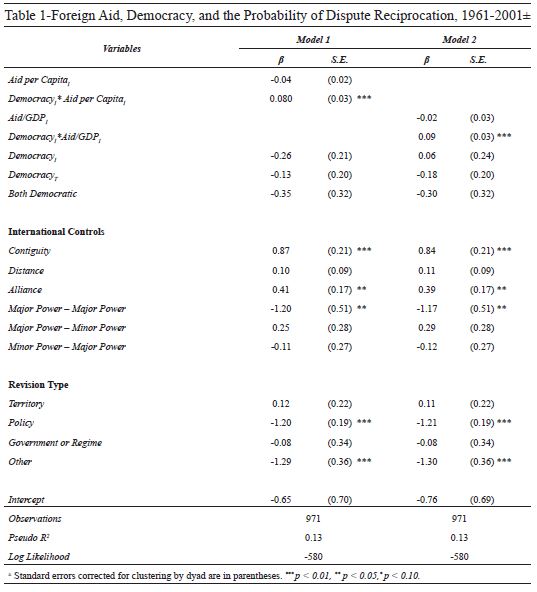

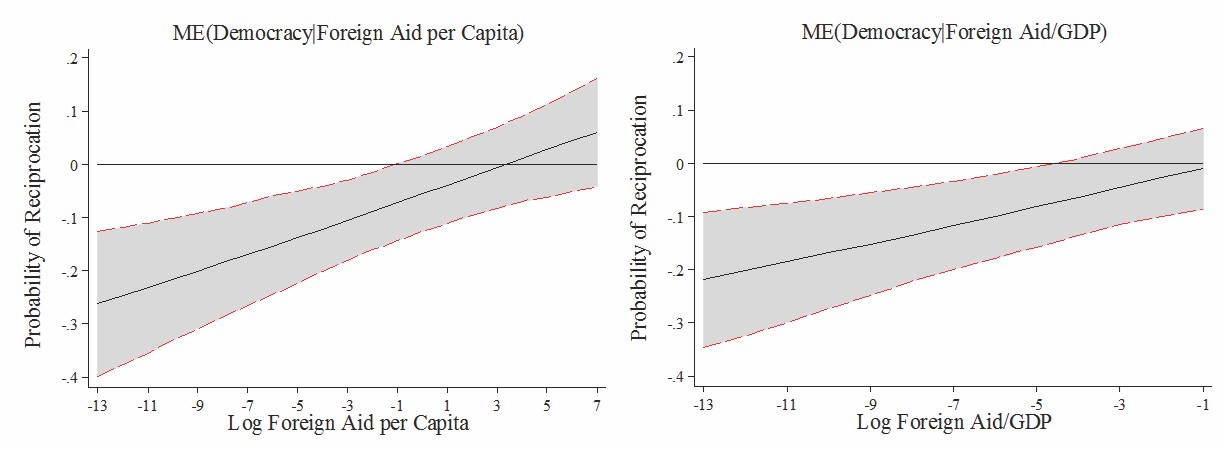

Table 1 reports the empirical results of analyzing all the reciprocation behavior of targets over the period 1961 to 2001. As the model includes an interaction term, the coefficients are not illuminating on their own, and we have to calculate substantively meaningful marginal effects and standard errors for each specification. Following the practice suggested by Kam and Franzese, I report the effect initiator regime type on reciprocation at different values of Aid per CapitaI and Aid/GDPI. In calculating the marginal effect of democracy on different values of aid on the probability of reciprocation, I set all other variables to their observed values. The observed-value approach varies only the parameters of interest, while keeping the other variables at their observed values, and averages out the political quantities of interest. Moreover, to calculate the uncertainty around these estimates, I create 1000 simulations of the probability of dispute initiation to approximate the distribution of the marginal effect of regime type at different levels of aid flows.

Figure 2: Foreign Aid, Regime Type, and Probability of Dispute Reciprocation

Notes: The figures present the marginal effect of changing regime type from a non-democracy to a democracy on the probability of reciprocation at different values of foreign aid and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The quantities of interest are extracted from Table 1, Model 1, and Model 2 by setting all other variables to their observed values.

The main results are reported in Figure 2, and they provide strong support for Hypothesis 1. Confirming the descriptive statistics presented in Figure 1, we observe that if a democratic state does not receive foreign aid, the disputes it initiates are significantly less likely to face resistance by the target. More substantively, if a state does not receive aid, a change in regime type from non-democratic to democratic decreases the probability of a reciprocation by 26% (Model 1 in Table 1) and by 21% (Model 2 in Table 1). However, as aid to a state increases, reciprocation behavior ceases to be different between democratic and non-democratic challengers, confirming the robustness of the bivariate relationship presented in Figure 1 to the inclusion of various control variables.

To summarize, for foreign aid to be effective in promoting aid growth, poverty alleviation, and improving quality of life, the presence of democratic institutions is essential. However, the very quality that increases aid effectiveness has important consequences during crisis bargaining: Foreign aid decreases the ex-ante probability of leader removal, hence, this surplus decrease due to aid makes it difficult to convince the target that the government’s re-election is at stake if it fails to follow through on its threat. This finding implies that the issued threat has no informational value for the target to distinguish resolved-type challengers from non-resolved types. As a result, both parties’ incentives to extract a larger concession on the table will prevent them from reaching a mutually preferable negotiated settlement. Thus, democratic states are not more peaceful to each other than other types of pairs as the aid flows they receive increase.

I now turn to the implications of the study for interstate peace.

5.2. Interstate peace

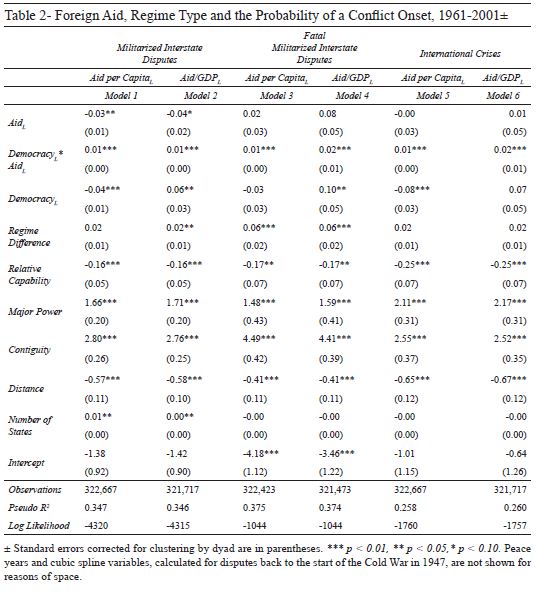

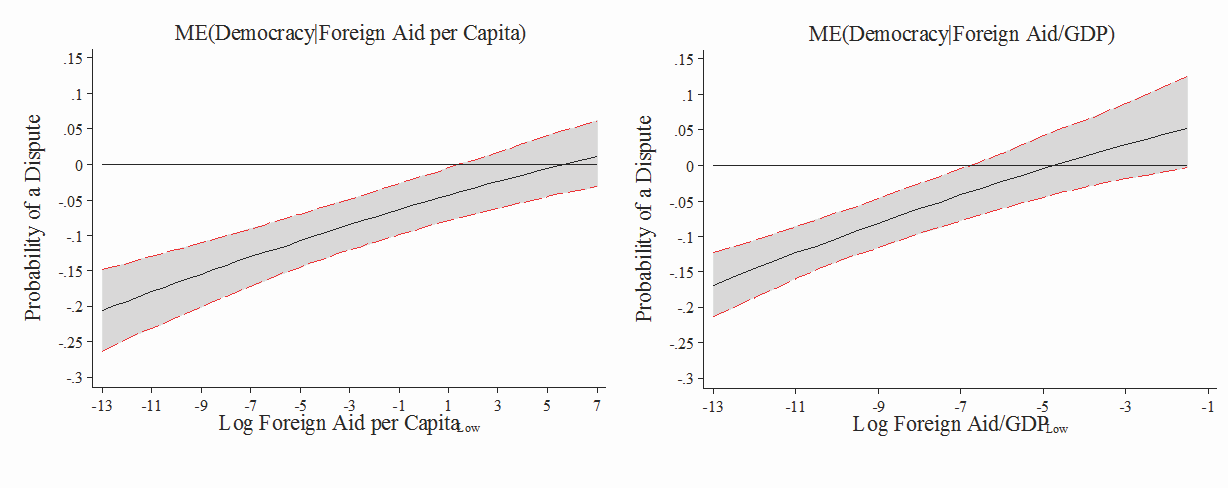

The results presented in Table 2 provide strong support for Hypothesis 2. Model 1 and Model 2 in Table 2 analyze the impact of foreign aid on the likelihood of an onset of all types of MIDs for the period 1961-2001. Militarized interstate disputes involve explicit threats, displays, or actual uses of military force. As the logistic regression coefficients are not illuminating on their own, Figure 3 reports the predicted probability of a MID onset in year t+1 by setting all other variables to their observed values. As evident in Figure 3, the marginal effect of changing the regime type of both states from the lowest democracy score (-10) to the highest democracy score (10) significantly decreases the probability of a MID onset by 20.6% in Model 1 and by 16.9% in Model 2 if both states do not receive foreign aid and if we set all other variables at their observed values. Holding aid at 0, the same amount of shift in DemocracyL decreases the conflict propensity of the dyad by around 48% when we consider the most conflict-prone scenario. However, as aid received by both states increases, the effect of democracy on the probability of a MID onset becomes statistically indistinguishable from 0, as predicted by Hypothesis 2.

Figure 3: Foreign Aid, Regime Type, and Militarized Interstate Dispute Onset

Notes: The figures present the marginal effect of changing regime type from a non-democracy to a democracy on the probability of a dispute onset at different values of foreign aid and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The quantities of interest are extracted from Table 2, Model 1, and Model 2 by setting all other variables to their observed values.

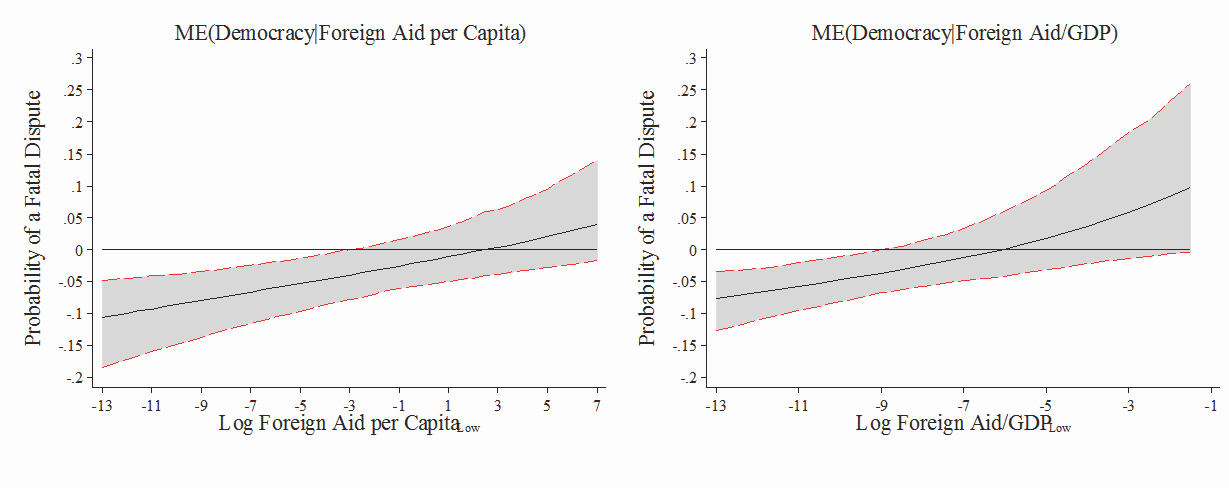

Audience-cost theory indicates that democracies can communicate resolve to each other without resorting to an actual fight. Hence, a reduction in audience-cost generation capacity is more relevant for bargaining failure if we observe an outcome that involves battle-related fatalities rather than ones involving only an exchange of explicit threats. As a result, to increase the leverage in testing the theoretical dependent variable, Table 3 adopts an alternative operationalization of conflict. Rather than analyzing all MID types, it analyzes the conflicts that result in battle-related fatalities: Fatal MIDs. Shifting attention to Fatal MIDs also allows us to avoid biases in MID reporting. For example, the media may be more likely to report non-fatal MIDs occurring in Europe than those occurring in Central Asia. However, if a MID involves at least one battle-related death, it is less likely to go unannounced in the international media regardless of its geographic location. Moreover, testing Hypothesis 2 in the context of Fatal MIDs serves as an additional robustness check for the findings reported here so far.

Models 3 and 4 in Table 2 replicate the first two models, except the dependent variable is now Fatal MIDs. The results reported using Fatal MIDs also confirm the findings in the specification using MIDs of all levels. Figure 4 presents the impact of the relationship between aid and dyadic democracy on the probability of a Fatal MID onset. As evident in Figure 4, the marginal effect of changing the regime type of both states from highly autocratic (-10) to highly democratic (10) significantly decreases the probability of a Fatal MID onset by 10.7% in Model 3 and by 7.6% in Model 4 if both states do not receive foreign aid. However, as the amount of foreign aid allocated to both states within the pair increases, the effect of democracy on the probability of a violent conflict onset becomes statistically indistinguishable from 0.

Figure 4: Foreign Aid, Regime Type, and Fatal Militarized Interstate Dispute Onset

Notes: The figures present the marginal effect of changing regime type from a non-democracy to a democracy on the probability of a fatal dispute onset at different values of foreign aid and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The quantities of interest are extracted from Table 2, Model 3, and Model 4 by setting all other variables to their observed values.

One last point warrants discussion: The Correlates of War project does not distinguish between conflicts that are intentionally initiated by key decision makers from those initiated without the direct authorization of the government, that is, those initiated by low-rank military officials operating at borders. Even though MIDs and Fatal MIDs record the non- authorized category as a conflict onset, the logic of audience-cost theory begs a more nuanced research design that allows analyzing conflicts that are intentionally initiated or escalated by the respective governments. Fortunately, the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) project’s dataset on interstate crises allows us to disentangle the conflicts initiated by key decision makers from those initiated by others. For the ICB project, a crisis occurs when key decision makers in a state “perceive a threat to one or more basic values, along with an awareness of finite time for response to the value threat and a heightened probability of involvement in military hostilities.” In addition to its value in testing the empirical implications of audience- cost theory, Hewitt suggests that when theories are supported in both MID and ICB settings, the results can be viewed more confidently and not as a function of any idiosyncrasies in one particular conceptualization, which further ensures result robustness across various definitions of conflict.

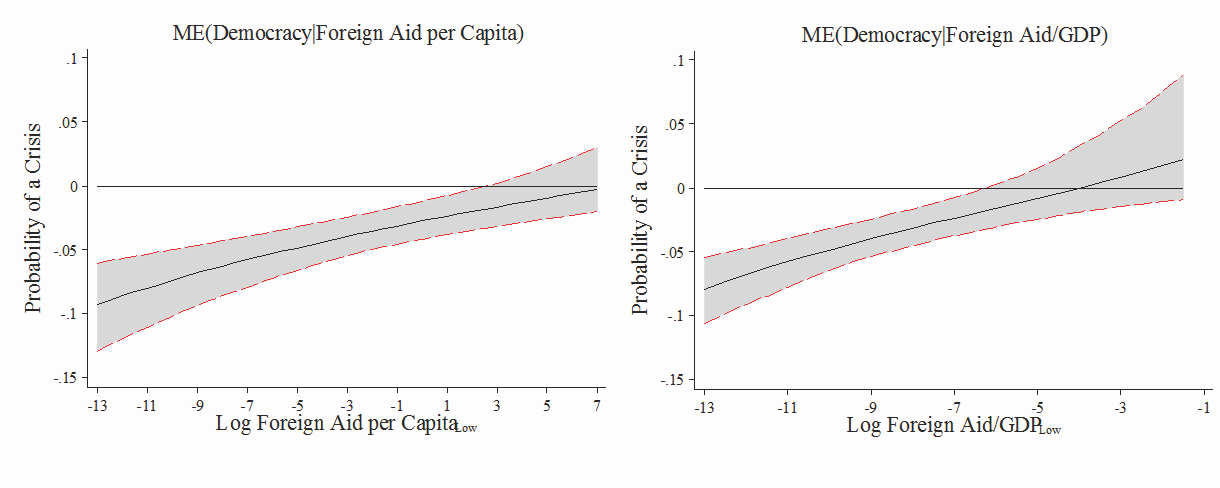

Hence, Models 5 and 6 go beyond MIDs and adopt the ICB project’s definition of crisis onset. The results are starkly similar to those reported in Models 1 to 4. All the variables have the expected signs and significance levels. Figure 5 presents the impact of the relationship between foreign aid and a dyadic democracy on ICB crises. As evident, changing DemocracyL from its minimum to maximum significantly decreases the probability of a crisis onset by 9.3% in Model 5 and 8% in Model 6 if both members of the dyad do not receive aid. Moreover, if we consider the most conflict-prone scenario, holding aid at 0, a shift in DemocracyL from its minimum to maximum decreases conflict propensity of the dyad from 93.31% to 19.87%, meaning a 73.4% decrease in crisis onset. However, as the amount of aid both parties receive increases, the effect of DemocracyL approaches 0 and becomes statistically insignificant, meaning that democratic peace does not operate as aid flows to both parties increase

Figure 5: Foreign Aid, Regime Type, and Crisis Onset

Notes: The figures present the marginal effect of changing regime type from a non-democracy to a democracy on the probability of a crisis onset at different values of foreign aid and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The quantities of interest are extracted from Table 2, Model 5, and Model 6 by setting all other variables to their observed values.

6.Conclusions

I began this study by recognizing that foreign aid, unlike the vast majority of explanatory variables used in conflict studies, is highly flexible for policy making. Therefore, scholars in the aid effectiveness literature as well as policy makers have focused on directing foreign aid to improve certain independent variables such as economic growth and poverty and inequality alleviation. In doing so, they overlook the fact that setting these variables at their most favored values sets other variables to undesirable and often the least intended values.

Drawing on the aid-effectiveness and audience-cost literatures, I show that foreign aid is highly fungible and the victim of grabber activities in non-democratic settings, whereas it is highly effective in improving citizen welfare in the presence of democratic institutions. Although this fact should be celebrated as an achievement in itself, the findings in this study indicate that not all good things go hand in hand: Autocratic leaders’ propensity to amass aid resources and keep them undistributed is dramatically higher than that of democratic leaders. Aid in democracies is almost completely spent on development projects, which increase citizens’ welfare and citizens’ perceptions of their respective government’s performance. As this surplus performance due to aid increases, governments remain in power until the surplus increase is undone through serious foreign policy failures. The implications of such situations are profound: Democratic governments lose their edge in credibly communicating their resolve to their opponents. As a result, targets cannot glean information about the willingness of an initiator by observing the initiator’s explicit threats because the surplus increase in governments’ re-election prospects decreases their ability to put their political survival at stake.

The analysis of reciprocation behavior indicates that targets resist less often against challenges issued by non-aid-recipient democratic states than those issued by non-aid- recipient non-democracies: The net average effect of changing the regime type of a non-aid-recipient polity from a non-democracy to a democracy decreases the target’s probability of reciprocating in kind or of escalating the dispute to a higher hostility level by 26% percent. However, as aid flows increase, the effect of initiator regime type becomes statistically indistinguishable from 0, meaning that foreign aid retards democracies’ ability to generate audience costs, hence, removes their ability to send informative signals to their opponents during crisis bargaining. This situation, in turn, removes the ability of democratic governments to reduce uncertainty about their relative resolve, which prevents them from reaching a mutually preferable negotiated settlement. The logical conclusion of this effect is straightforward: Democracy does not operate as a cause of peace among aid-recipient states; the net average effect of changing the regime type of two non-aid recipient states from autocratic to democratic decreases the probability of a MID onset by 20.6%, a Fatal MID onset by 10.7%, and a crisis by 9.3%. However, as the amount of aid both states receive increases, the effect of democracy becomes statistically indistinguishable from 0.

This study is not only of theoretical relevance, but also suggests practical implications for policy makers. In order to aid peace among democracies, aid donors should at least condition foreign aid to posterior annual public announcements of how each cent of aid money is consumed within the recipient country. In that way, the average citizen in democracies will be able to differentiate between the actual performance of the government and the surplus benefits they enjoy due to foreign aid. Otherwise, unable to make this separation, citizens will be more tolerant of government foreign policy failures as long as they enjoy the surplus benefits that come as a result of aid, as they would assume the real cause was the government’s domestic policy performance. Failure to adopt this policy suggestion will not only make domestic politics less competitive, but also give the government with a higher level of foreign policy failure threshold, therefore more likely to adopt more risky foreign policies.

This option is, however, not the only one available to policy makers. There are two others that may also prove helpful to reach the desired outcome of peace. First, aid donors should place a non-belligerence condition on the recipient country and require peaceful resolution of the dispute of interest. For example, after the Baltic States achieved independence in 1991, the Estonian and Latvian governments’ non-recognition of Russian minorities’ citizenship status brought both countries to the brink of war with Russia. Western bilateral donors and regional organizations prevented a war through promises of aid in exchange for recognition of citizenship status and the associated rights and privileges.

Apart from this opportunity-cost perspective, conditioning aid disbursement to non- belligerence of the recipient countries can also prove useful in compensating for the problems aid poses during interstate crisis bargaining. On the one hand, foreign aid reduces leader ability to put their survival at stake if they fail to follow through on their previous threats, as discussed throughout the study. On the other hand, aid-recipient governments can use foreign aid commitments, the disbursement of which is conditioned on non-belligerence, as a way to credibly communicate their resolves through costly signaling without resorting to violent conflict. If both parties know the initiator will have to face drastic cuts in foreign aid in response to its belligerence, a recipient government can reveal private information about its resolve by issuing a threat that will be retaliated by its donors. However, for this mechanism to work, the donor should (1) have a very high sensitivity to a threat to use force, (2) be clear about the types of threats that will face punishment in aid disbursements, and (3) ensure that the amount of aid is high, so that it has a signaling value.

However, the main policy implication proposed in this study, an annual announcement of what portion of aid resources are responsible for a surplus increase in an average citizen’s welfare in a given year, is the least costly option for donors and recipients. This policy implication may not only keep recipient governments more peaceful, but also increase positive attitudes toward the aid donor. To conclude, these findings on the relationship between foreign aid and crisis bargaining is novel, yet profound knowledge. To serve the cause of peace, international relations scholars and policy makers must heed the lasting effects of this powerful and highly malleable instrument of war and peace.