1.Introduction

When we look at the ‘grand theories’ to explain social and economic crises, such as those postulated by Marx, Schumpeter, Polanyi, and to some extent Keynes, all, even if they have different world views, agree on the ‘self-destructive’ power of capitalism that surfaces during these crises. The common ground among these theories is the institutional problems and imbalances that are created by unharnessed and expansionist capitalism. According to Marx and Schumpeter, this feature of capitalism will result in capitalism terminating itself endogenously. While Keynes advocates government intervention to eliminate these imbalances, Polanyi asserts that protectionist movements and regulatory policies must emerge endogenously to protect capitalism from destroying itself and from deteriorating society, a concept he calls double movement.

According to Polanyi, double movement is the end result of self-regulating markets, whose functioning requires commodification of labor, land, and money. Polanyi explains this process as an unnatural and inhumane procedure. For example, in the course of labor commodification, human beings become agents who sell their labor, which is only possible through the separation of economic life from social life. Economic life necessitates rational, self-interested, atomized hermits isolated from their social lives, for example, as fathers and mothers, friends, and citizens. This division results in constant struggle between these two roles, which leads to rising social problems and to fundamental changes in the economic and social structure as a counter movement. Similarly, the environment is being destroyed as a result of this commodification process. Although at first glance, protectionism, and for this purpose, regulating capitalism, looks like a remedy for such problems, intervention creates many problems of its own and much tension in self-regulating markets. Interference contradicts with the workings of capitalist institutions, creates new crises, and leads to catastrophe, such as occurred with the rise of fascism in the 1930s.

To summarize, the continuous tendency to expand self-regulating markets, and reaction to that expansion to then protect human beings and society from its effects, creates ongoing counter movements between liberalism and protectionism. Indeed, when global economic policies are examined as swings of a pendulum between protectionism and liberalism, three eras since the Industrial Revolution can be identified, both at the domestic and at the international level:

- First Globalization: 1870-1914 and the Interwar Years: 1914-1944;

- Postwar Period and the Rise of the Welfare State: 1944-1973;

- Collapse of the Bretton Woods System and Second Globalization: 1973 onwards

The paper continues as follows: First, the periods are explained from the perspective of the double movement notion, with an emphasis on swings of the pendulum between liberal and protectionist economic policies. For this purpose, Section II explains the swings by categorizing the above-noted eras as liberal between 1870 and 1914, protectionist between 1944 and 1973, and liberal from the early 1970s until today. The second part of the paper shows that the recent European crisis and political formations are not independent events. On the contrary, they are just a continuation of the latest liberal swing, in accord with Polanyi’s double movement notion. To elucidate this point, Section III questions the EU economic imbalances by focusing on the relationship between the periphery and core countries, which started with the introduction of liberalization procedures to become a single, big, homogenous market. The main aim of this section is to study the reasons for the imbalances that triggered the European crisis by examining the flaws of the Maastricht Treaty as a design for the region’s monetary union. The last part of the article connects Polanyi’s ideas to the consequences of the Euro crisis.

2.Swings of the Pendulum

Polanyi himself explains the first era (between 1870 and 1930) as the struggle between liberal and protectionist ideologies. He starts with the industrial revolution and the enormous welfare and growth increase that also resulted in major social problems over the following 60 years.

The four main institutions of nineteenth-century Western civilization – the so-called four pillars, which helped encourage capitalism until the 1930s – began to collapse under capitalist expansion. The first pillar was the balance-of-power system, which prevented the occurrence of long and devastating wars among the Great Powers. The second was the international gold standard, which symbolized a unique organization of world economy. Financial and capital liberalization across nations was guaranteed mainly by this system. The third was the liberal state, which ensured the workings of self-regulating markets, themselves the fourth pillar.

2.1.The first globalization and the interwar years: A liberal era

During the first pendulum swing, the domestic and international institutions noted above worked well in the service of self-regulating market economies. Core European countries were growing steadily and avoiding big wars. This stability lasted for 100 years, until the beginning of the twentieth century, when the four pillars began crumbling. The balance of power was changing because of colonial rivalries among strong nations. Within nations, liberal ideologies were losing ground due to a counter movement in the form of socialism, and the international gold standard system was creating instabilities. Still, the gold standard would wait until the 1930s to collapse, which would bring down the unharnessed, free markets. Under these conditions, the First World War was inescapable.

After the war, big changes occurred in the world order. Countries had suspended the gold standard system to finance the war, and after the war, they wanted to return to that system, despite economic obstacles. Because of excessive war spending, inflation rates had increased in many countries. Thus, returning to the gold standard at pre-war prices required deflation, which meant unemployment. While citizens, and therefore government, had accepted deflation and unemployment before the war, the spread of democracy, socialism, and powerful trade unions meant that governments could no longer ignore such issues. These institutional changes were the result of the counter movement to liberal markets at the class struggle level as part of the double movement notion, which occurred gradually during the liberal era. Under the new circumstances, deflation was creating adverse effects on the economy because wage cuts were not viable in labor markets but prices were decreasing. Consequently, labor was becoming expensive and output was declining. The changing and developing institutions, i.e. labor unions and minimum wage regulations, built up as a counter movement to self-regulating markets and were hampering the latter’s smooth functioning. After great efforts to resurrect the gold standard in the 1920s, by the dawn of the 1930s, beginning with the UK, countries began to discard it.

2.2.The postwar period: The rise of the state

In 1929, the Great Depression further shocked the world economy, lasting until the mid- 1940s. Polanyi explains the Depression as one of the consequences of the hopeless efforts of the world’s main economies to save the gold standard: The US was trying to back up the British pound by decreasing its interest rate to avoid capital flow from the UK. However, this triggered a credit expansion and boom that led to the bust of 1929. All global economies were badly affected by this crisis and trust in liberalism was losing ground, which led to the rise of totalitarian regimes in 1930s’ Europe, such as in Germany and Italy. At this point, we can turn to Polanyi’s important idea that the “rise of fascism was the result of the liberal utopia of self regulating markets.” These events prepared the ground for the Second World War, which ended the liberal era: the pendulum began to swing toward protectionism.

After World War I, Keynesian economics, which advised harnessing capitalism, gained popularity around the world. Thus, in the second swing of the pendulum, the liberal focus was replaced by a protectionist movement and the welfare state idea. This wave continued until the late 1970s in Europe. The Keynesian idea pinpointed government engagement and regulations in economic management, and this advice was followed in many economies. A new international monetary system, Bretton Woods, was established during this time.

Bretton Woods was another fixed exchange rate system, yet quite different than the international gold standard. The open economy trilemma asserts that fixed exchange rate regimes can only be combined with monetary autonomy at the expense of unrestricted capital mobility. It follows, therefore, that unrestricted capital mobility can only be combined with monetary autonomy at the expense of a fixed exchange rate regime. To put it another way, the international gold standard regime was a fixed exchange rate regime, and it was combined with unrestricted capital mobility and no monetary autonomy. Thus, there was no monetary policy application among the rules of the game. During the heyday of this system, liberal ideas prevailed, which did not advocate economic policy applications anyway. After the 1940s, however, together with protectionism and regulations, monetary policy implementations began to gain importance. Keynes himself, as the British representative at the Bretton Woods, New Hampshire conference that developed (and was a namesake for) the new system, wanted a much more flexible system than the gold standard, in which monetary policies would be an important tool. Because Bretton Woods was a fixed exchange rate system combined with monetary autonomy, consequently, according to the trilemma, capital controls must be restricted. In these respects, – flexibility and capital controls – Bretton Woods was different than the international gold standard system. However, these properties were also the causes of its instability. Although capital mobility was restricted, speculators found ways around this by borrowing from abroad, by delaying payment for goods, or by lending by forwarding money in advance.

Nevertheless, the main problem for Bretton Woods came from the US. In Bretton Woods, the US dollar was the only currency fixed against the price of gold: 1 ounce of gold was $35. All other currencies in this system were fixed in value against the dollar. Although the US committed to preserve the dollar price of gold, it could not uphold that promise. Its involvement in the Vietnam War doubled inflation in the country, which meant overvaluation of the dollar. Eventually, the US devalued the dollar to preserve the system but it could not stop inflation, and gold convertibility was finally abandoned in 1973. This was the end of the Bretton Woods international monetary system. This event, along with other problems that we touch upon briefly in the next section, created a loss of confidence in Keynesian ideas and directed the pendulum toward liberal policies again.

2.3.The swing toward the second globalization and liberalization: 1973 to today

Although the Bretton Woods system was prone to destabilizing properties, with the help of some convenient recovery conditions after World War II, such as high profits and investments and technology transfers, Keynesian policies delivered almost 25 years of growth around the world, between 1950 and 1973. This period was called the Golden Age. However, the political economy of demand management tended to make politicians more willing to increase spending in difficult times than to raise taxes in good times, and as a consequence, most Western economies built up considerable debt in the 1970s, which increased their inflation rates. Another problem in this period was the supply shock due to the increasing price of petrol, and for the first time, stagnation and inflation were seen together. The name of this crisis was stagflation. Liberals agreed that it was the consequence of too much government regulation, which resulted in increasing inefficiencies, i.e., increasing production costs, because of constant intervention in markets. According to this thinking, another counter movement was necessary to allow self-regulating markets to function smoothly again. These ideas began the most recent swing to liberalization, but this era has also witnessed important crises: the global crisis of 2007 and 2008 and the Eurozone crisis. These crises shared some similar sources, such as monetary expansion after the 1990s. The general glut of savings in developing Asian countries, which provided ‘cheap money’ for the world, especially affected both crises. This point was underlined by economist Ben Bernanke in a speech about financing the US current account deficit. From this standpoint, we cannot think of the Eurozone crisis as an independent event from the global crisis. On the contrary, it is a continuation of the events that started with financial deregulations and affected the US and other countries in the world in terms of easy access to other countries’ savings. Nevertheless, the Euro crisis also had its own and different stimuli. It can be said that even if the global crisis had not played a catalyzing role, the Eurozone would still have been prone to crisis.

Some studies of the Eurozone crisis focus on the fiscal debt created by the periphery countries.However, other studies show that, except for Greece and Italy, governmental fiscal debt was not endemic to the periphery in the Eurozone. If we look only at the GIPSI countries (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy) their average debt/GDP ratio had declined from 88% to 75% between 1999 and 2007, before the Eurozone crisis. In addition, increasing indebtedness of many of the European periphery countries since the early 2000s stemmed not from government debt but from private debt. These findings suggest looking for alternative views to the Eurozone crisis rather than focusing only on the fiscal debts of some countries as the sole reason for it.

3.Euro Zone Deregulation and Imbalances

3.1.Liberalization in the EU toward a single market

After the collapse of Bretton Woods and with liberalization beginning in the second globalization era, around the world nominal deregulations were accelerating in Europe as well. During the1980s and 1990s most countries in the EU lifted capital controls and deregulated interest rates to achieve a ‘single market’ in the financial system (Table 1). These regulations were the antecedent of the Maastricht Treaty (1992), before the introduction of the Euro in 1999. The Maastricht Treaty focused on the economic convergence necessary before the EU countries could undertake a common currency. The idea of the convergence criteria adopted in the EU and the EMU (European Monetary Union) was followed by postulates of the “theory of optimum currency area.” Optimum currency area requires both real and nominal convergences among regions that form the Union. Yet, in the Maastricht Treaty, mostly only nominal convergence criteria were laid down, such as convergence in inflation, exchange rate, and interest rate. Budget deficit-to-GDP ratio and government debt-to-GDP ratio were confıned to three percent and 40% respectively among the member countries.

Convergence in real terms, such as productivity rates, were overlooked and probably left to the workings of the market forces. Or perhaps, if convergence in real terms was considered, examining it was postponed, given the difficult and long-term nature of the issues, such as fiscal convergence.

Table 1- EU Chinn-Ito Index of Capital Account Liberalization for Selected Country Groupings (1990-2009)

|

1990-1994 |

1995-1999 |

2000-2004 |

2005-2009 |

| Core Countries |

83.2 |

96.1 |

97.4 |

100 |

| Non-Core Countries |

19.5 |

80.5 |

96.6 |

100 |

| Other Euro Countries |

-37.9 |

-9.5 |

24.7 |

81.3 |

| Non-Euro Countries |

8.8 |

39 |

66.9 |

87.9 |

Source: E.P. Caldentey and M. Vernengo “The Euro Imbalances”. According to the Chinn-Ito index, a value of 100 means complete liberalization. Core countries: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Non-core countries: Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Other Euro countries: Estonia, Malta, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia. Non-Euro countries: Sweden and the United Kingdom.

3.2. Intra-area imbalances

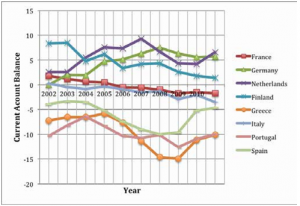

The adverse economic effects of the Maastricht Treaty and other issues in attaining a single market stemmed from two intertwined channels. One problem was fixing exchange rates among member countries to eliminate competitive exchange rate devaluations. However, devaluating exchange rates is not the only way of becoming competitive. If a country’s wages are lower than its productivity, wage deflation is created, and decreasing production costs increases a country’s competitiveness. Bibow convincingly explains how this strategy has been applied by Germany since the 2000s to boost its exports and consequently create current account imbalances in the EU. Importantly, the decline in labor cost was not due to any acceleration in productivity growth, but in wage restraint, which gave an extra push to German exports. Austria, Finland, and the Netherlands were other countries with relatively low labor costs and thus current account surpluses. Bibow adds that these countries used the surpluses to consolidate their own public finances to match the Maastricht Treaty regulations.24 However, labor costs were higher in periphery countries such as Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. With the regulations after Maastricht, these countries lost the ability to devaluate their exchange rates to compete with core countries. This situation directly decreased their exports and increased imports within the union, and they started to run current account deficits, in contrast to the core countries that had current account surpluses (Graph 1). The labor market convergence thus did not occur as it was supposed to.

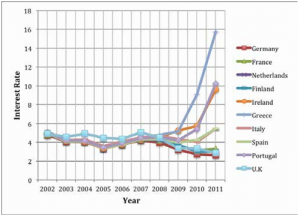

The second problem was credit expansion. Together with interest rate convergence, which lowered interest rates, and deregulation of capital movements in European countries, borrowing became easy (Graph 2). Consequently, core countries’ surpluses were flowing to periphery countries to fund their deficits. Capital inflow to the periphery was decreasing interest rates even further and hence increasing the likelihood of bubbles, as had happened in the US. The reckless global adventures of European banks were also increasing the possibility of crisis. Indeed, housing bubbles were created in Ireland, Spain, and Italy. Between 1996 and 2006, house prices increased as much as 182% in Ireland, 115% in Spain, and 51% in Italy. The private indebtedness of these countries increased till the bubble burst and gave way to the European crisis following the global crisis. Not all countries were subject to bubbles, but they were still put in a fragile position because of their current account deficits. Especially for countries such as Greece, that also had problems such as high public debts, the global crisis created detrimental effects. Worst of all, countries’ abilities to use countercyclical policies were hampered by the Maastricht Treaty and there was no supranational institution to instill proper fiscal policies when the system failed.

Graph 1: Current Account Balance in Selected Eurozone Countries.

Source: Eurostat yearbook 2012

Graph 2: Interest Rate Convergence in Selected Countries.

Source: Eurostat yearbook 2012.

4.Final Thoughts

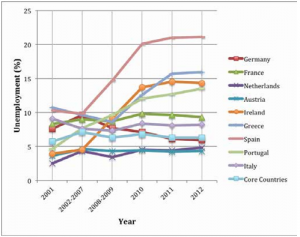

The 2007 crisis exacerbated the economic conditions of the Eurozone. Increasing sovereign debt due to bailouts reached an all-time high of 92.2% of the zone’s GDP in 2013. Production decreased by 1.8% in 2009. Increasing unemployment rates (Graph 3), austerity measures, and decreasing wages and social benefits also ensued. As Feldstein mentions, some of the countries would clearly have had lower unemployment, a smaller national debt, a more- competitive international position, and better prospects for the future had they had never been part of the EMU. Also, political relations within Europe would be less confrontational. Indeed, the recent picture reflects disintegration, rather than integration, especially for the periphery. However, negative economic effects are not the only outcomes; other important implications for the future of Europe and the world also must be noted. The recent European Parliament Elections showed that far-right movements with similarities to 1930s fascism received a significant number of votes: The Front National in France (25%), Golden Dawn in Greece (10%), the Danish People’s Party in Denmark (27%), Party for Freedom in the Netherlands (12%), the Freedom Party in Austria (20%), and Jobbik in Hungary (15%). Members of Jobbik have called for Jews to sign a special register on the grounds that they might pose a “national security risk.”

Since the Second World War, Europe has been the citadel of individual freedom, multiculturalism, tolerance, social progress, and welfare. So what is happening in Europe now? Seeking an answer to that question leads to Polanyi: When liberal ideas start to lose ground because of economic problems, fascism resurfaces. Indeed, the last crisis did just that. The center right has been discredited while the left has either colluded with austerity or lost its proletarian soul, which paves the way for the far right.

How did Europe reach this point? Polanyi’s double movement mechanism can be traced quite explicitly in the history of the Eurozone crisis. With the last swing, after the liberalization of the 1970s, the Eurozone began to regulate for deregulation to be a competitor in the globalizing world. There was great faith and trust in free markets. If Europe could become one big market excessive advantages such as increasing trade, demand, and growth would be realized. However, deregulation with the purpose of establishing a monetary union, but without taking into account countries’ heterogeneity, was a grave error. By leaving the real convergence to the workings of the free markets, the EU implemented the same currency with a common Central Bank, but did not establish fiscal centralization. Free markets did not work as predicted, as we saw in the labor markets and current account situations. On the contrary, imbalances occurred and led to the crisis. We can think of this procedure from the point of view of Polanyi’s double movement mechanism. According to Polanyi, free markets do not have a solution for this type of crisis; government institutions must do the work, but in the Eurozone situation, government hands were tied because of EU regulations. Consequently, corrective fiscal and monetary policies could not be implemented, which exacerbated the problems. Thus, the consequences of the Eurozone crisis were political as much as economic.

Do people learn from their mistakes? As Caldentey and Vernengo state,

Imbalances in a Monetary or Currency Union are bound to occur when its state members are economically heterogeneous and different. Recognition of this fact requires that the establishing Union must create, as part of its constituent, charter mechanisms to solve and clear the imbalances―rather than making them cumulative over time.

This kind of approach may soften the pressures that are created by difficult economic conditions that generate crisis, which is also implied by Polanyi. For each country, instead of only pursuing their self-interests and becoming rival atoms at the national level, pursuing solidarity and interlocking with each other would be much more beneficial in the long run.

Graph 3: Unemployment Rates.

Source: Adapted from Caldentey and Vernengo, “The Euro Imbalances.

Appendix of Tables

Table 1- Current Account Balance in Selected Eurozone Countries

|

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

France |

1,8 |

1,2 |

0,7 |

0,5 |

-0,5 |

-0,6 |

-1 |

-1,7 |

-1,5 |

-1,7 |

|

Germany |

0 |

2 |

1,9 |

4,7 |

5,1 |

6,3 |

7,5 |

6,3 |

5,6 |

5,7 |

|

Netherlands |

2,6 |

2,6 |

5,5 |

7,6 |

7,4 |

9,3 |

6,7 |

4,3 |

4,2 |

6,6 |

|

Finland |

8,4 |

8,5 |

4,8 |

6,2 |

3,4 |

4,2 |

4,3 |

2,6 |

1,8 |

1,4 |

|

Greece |

-7,2 |

-6,5 |

-6,5 |

-5,8 |

-7,6 |

-11,4 |

-14,6 |

-14,9 |

-11,1 |

-10,1 |

|

Italy |

0,3 |

-0,4 |

-0,8 |

-0,3 |

-0,9 |

-1,5 |

-1,3 |

-2,9 |

-2 |

-3,5 |

|

Portugal |

-10,3 |

-8,2 |

-6,4 |

-8,3 |

-10,3 |

-10,7 |

-10,1 |

-12,6 |

-10,9 |

-10 |

|

Spain |

-3,9 |

-3,3 |

-3,5 |

-5,2 |

-7,4 |

-9 |

-10 |

-9,6 |

-5,2 |

-4,6 |

Source: Eurostat yearbook 2012

Table 2- Interest Rate Convergence and Decrease before and during the Crisis for Selected Countries

|

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

| Germany |

4.78 |

4.07 |

4.04 |

3.35 |

3.76 |

4.22 |

3.98 |

3.22 |

2.74 |

2.61 |

| France |

4.86 |

4.13 |

4.10 |

3.41 |

3.80 |

4.30 |

4.23 |

3.65 |

3.12 |

3.32 |

| Netherlands |

4.89 |

4.12 |

4.10 |

3.37 |

3.78 |

4.29 |

4.23 |

3.69 |

2.99 |

2.99 |

| Finland |

4.98 |

4.13 |

4.11 |

3.35 |

3.78 |

4.29 |

4.29 |

3.74 |

3.01 |

3.01 |

| Ireland |

5.01 |

4.13 |

4.08 |

3.33 |

3.76 |

4.31 |

4.53 |

5.23 |

5.74 |

9.60 |

| Greece |

5.12 |

4.27 |

4.26 |

3.59 |

4.07 |

4.50 |

4.80 |

5.17 |

9.09 |

15.75 |

| Italy |

5.03 |

4.25 |

4.26 |

3.56 |

4.05 |

4.49 |

4.68 |

4.31 |

4.04 |

5.42 |

| Spain |

4.96 |

4.12 |

4.10 |

3.39 |

3.78 |

4.31 |

4.37 |

3.98 |

4.25 |

5.44 |

| Portugal |

5.01 |

4.18 |

4.14 |

3.44 |

3.91 |

4.42 |

4.52 |

4.21 |

5.40 |

10.24 |

| UK |

4.91 |

4.58 |

4.93 |

4.46 |

4.37 |

5.06 |

4.50 |

3.36 |

3.36 |

2.87 |

Source: Eurostat yearbook 2012