1. Introduction

Over the years, various debates, multiple paradigms, a number of new methods and forms of data, as well as the incorporation of input from other disciplines, have given International Relations (IR) a remarkable level of sophistication. Indeed, there are few other disciplines that are more open to fundamental criticism, inter-disciplinarity, and input from non-academic sources than is IR. IR has also been widened as some formerly understudied--mostly non-Western--phenomena have found their way into mainstream scholarship.

IR’s inclusiveness, however, does not apply to International Relations Theory (IRT), which remains imperfect as a tool for understanding and explaining the newest and often more problematic parts of contemporary international relations. Overwhelmed by an expanding ontology, IRT has failed to explain and foresee the most momentous international events of recent decades. Consider the surprise over the Iranian revolution, over the irrationality of suicide attacks after 9/11, or more recently, over ISIS’ efficiency. Being under-theorized, such novel phenomena are approached using concepts usually alien to the context, and ultimately unhelpful in understanding or addressing the needs surrounding these issues.The incongruence is not limited to rationalist/positivist IRT, but extends to post-positivist theories. Our supposedly revolutionary new concepts and approaches remain largely insufficient in explaining what happens globally and in offering lessons for improvement.

This deficiency can only be addressed by building more relevant theories. For theory to be relevant in accounting for contemporary international relations, we argue, it should not only apply to, but also emanate from different corners of the current political universe. The main obstacle for IRT, then, is arguably the exclusion of the periphery from original theory production. A growing literature points to the conditions augmenting this exclusion. The impediments range from peripheral conditions and attitudes such as skepticism/indifference towards social sciences in general and theory in particular, or lack of resources and institutional support, to the global “hegemonic status of Western IR theory that discourages theoretical formulations by others”. The global hegemonic structure of the discipline pushes periphery scholars to be consumers of theory, rather than producers of it.

Despite the general agreement on the need and ongoing efforts to enrich IRT with periphery voices, there is a major divide in terms of how this can and should be done. Many argue that the best way is to have periphery IR scholars tackle with the primary questions of the core and try to modify, criticize, and improve upon existing theories. This view is advocated by more positivist leaning scholars, since they see no fundamental difference between theorizing in the core and in the periphery, except in the material conditions of scholarship. Hence, their suggestion is to improve those conditions for the periphery scholar. Interestingly, this is also the route preferred by advocates of “post-Western” theory, who share an “intuition that greater incorporation of knowledge produced by non-Western scholars from local vantage points cannot make the discipline of IR more global or less Eurocentric.” They usually point to the role of underlying nationalistic ideology in bringing about distinctively ‘non-Western’ theories, and they argue that such endeavors only serve to recreate the relationship between the core and periphery. They warn against any project that is self-admittedly ‘non-Western’ but emulates the dominant forms of thinking (including methodology) in the West. This conviction also emanates from a belief in the falseness of the West/non-West dichotomy, hence the preference for the term ‘post-western’.

The proponents of this first route are missing a few major points. First, submerging oneself within mainstream concepts and debates and trying to work from within the system, is not particularly viable for periphery theorists. It is extremely hard for the periphery scholar to find a spot for herself/himself within the core theory circles, requiring at minimum a fully Western post-graduate education and training in Western methodologies and language. Socializing into this competitive environment requires imitation and utilization of those core ideas as reference points; for otherwise periphery scholars are regarded as less than competent. Therefore, for the voice of a periphery scholar to be heard in the core debates, whether to criticize or otherwise, s/he has to be fully immersed within that community and forego any periphery perspective.

Secondly, core theoretical debates are, frankly, not generally open to empirical input from the periphery. Even when they are, the expectation for periphery-inspired work is that it support the core theories, rather than amend or correct them. Thus periphery scholars become “social-science socialized” producers of local data, who are expected to support mainstream theories, and operate as “native informants”. Becoming a “theorist” in the periphery means risking “becoming nobody” in the global community. In the rare instances when a periphery scholar nevertheless attempts to “do theory,” their work is likely to be dismissed as not being “theory”. This attitude highlights the dichotomy between “theory” and “local” that is imposed on the periphery scholar. Under these conditions, this first option degenerates into hiring new labor for the same task and the same purpose. Indeed, such a course of action sounds like a perfect recipe for the perpetuation of marginalization under the guise of pluralism, akin to the self-promotion of 'ethnic food' or 'world music' in contemporary Western societies.

Lastly, attempts by a few very competent periphery scholars to take up the first route have met with little success. For example, Ayoob actually tried to amend realist understandings of security by bringing in input from the Third World, but his ideas did not resonate. Similarly, Xuetong’s attempts to revise realism did not lead to substantial debate within the core. Such efforts have not managed to enrich ‘core’ theory with widened perspectives.

We see more merit in the second option, i.e. to build directly on the richness of these periphery lands, their history, practices and experiences. A genuine attempt to widen the world of IRT requires periphery voices acquiring their theorizing agency first, and this can only be done if their experience can serve as a source for unique new theorizing efforts and perspectives. Before trying to cram periphery feet in the core’s glass shoes, the discipline needs to see what those in the periphery themselves have to offer. Neither does it help to relegate the periphery’s voice to one of criticism only. Such a shattering of the glass shoes, i.e. showing that core concepts do not fit in the periphery, does not itself provide a wearable, efficient pair of shoes. In other words, “post-Western” perspectives often offer little to move beyond ‘the West and the non-West’. Diversity and dialogue can only come about when periphery scholars do not just ‘meta-theorize’ but also ‘theorize.’

Therefore, the increasing irrelevance of IRT needs to be addressed by a new form of theorizing, one which effectively blends peripheral outlooks with theory production. We call this form “homegrown theorizing,” which is defined here as original theorizing in the periphery about the periphery.

This definition may warrant further definitions. We deal with them in more detail in the next section, but can summarize our criteria as follows. First, for any idea/approach/perspective to be considered as theory it should propose a relationship between at least two concepts. This is a methodologically neutral definition acceptable by both positivists and post-positivists, even though they disagree on the nature of the relationship: for positivists it must be causal, for post-positivists it is constitutive, at best. Second, for any theory to be original at least one of these concepts must be either novel or redefined. While suggestions for new methods to operationalize extant concepts are also inventive, they remain in the purview of the original theory, and as such do not warrant substantial revision. Finally, for any original theory to be homegrown, it should be based on indigenous ideas and/or practices. It is our conviction that the disciplinary culture values scholarly work that fulfills the originality criteria, but is oblivious to the diversity that might be achieved by fulfilling the third one. This paper intends to highlight that potential.

Two caveats are in order. First, to label something as ‘homegrown’ we are not concerned with the ethnic/national identity of the author, rather, with various aspects of how the non-core experience is drawn on and conceptualized. Second, we prefer to use ‘periphery’ over ‘non-Western’ despite the ambiguous meaning of ‘periphery’ because it inherently evokes the subaltern agency in a hegemonic relationship. So the criteria we propose can be used with respect to theorizing anywhere that has been considered as peripheral in some respect. For example, it can be applied to IRT in Western Europe –considered peripheral in comparison with the US, but part of the core in comparison to elsewhere. Nonetheless, in this article, we focus on homegrown theorizing from outside of both North America or Western Europe, as that is what is generally seen as underdeveloped or even non-existent, mostly under-recognized, yet increasingly important.

A typology of homegrown theories based on the differences in their production serves three purposes. First, it makes dealing with homegrown theories a more systematic endeavor by providing a guide for recognizing original theory building in the periphery—not necessarily an easy endeavor for a phenomenon that is considered “hidden” or “unrecognizable”. Most of the extant reviews of theorizing outside of the core currently rely on geo-cultural categorizations, such as “Chinese” or “Japanese” international relations theory or independent theorizing in “emerging powers”, or in a specific country. These geo-cultural categorizations may be helpful from a “sociology of the discipline” perspective but are inadequate in identifying the most valuable efforts to theorize international relations stemming from outside the US/Europe. For example, “pure theory” in the periphery refers to discussions about mainstream theories and may not translate into original theorizing. An article on game theory and rational choice that is written by a Chinese scholar may be original but “bear no traces whatsoever of ‘local theorizing’”. However, by defining what is actually ‘homegrown’ in any theory, and categorizing theories accordingly, we can explain just how original and homegrown theorizing is. Focusing on the homegrownness of the idea, rather than on the background of the theorist, we identify degrees of being original as well as identifying the elements of a theory that can be original, adapted or borrowed. By contrast, saying only that a particular theory is “hybrid” tells us little about in what ways it is the same as or different from mainstream theory.

The second purpose of having a typology of homegrown theories is to reveal that different forms of original theory building are not only possible, but have already taken place. By offering a typology, we aim to move beyond general categorizations of approaches to homegrown theorizing--such as “particularism,” “provincialization,” or “denationalization” --to suggesting specific methods for building homegrown theories.

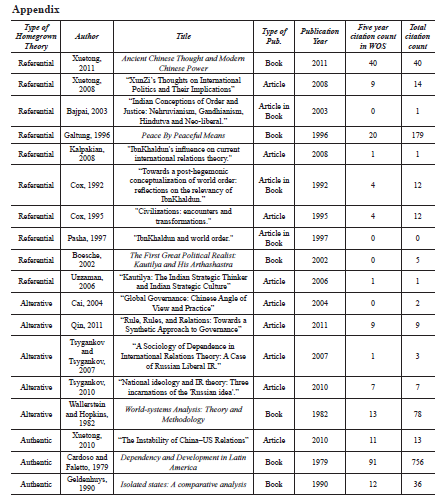

Our third purpose is to identify the prospects and challenges associated with different types of homegrown theories in terms of their potential for recognition. To do this, we collected a sample of 18 works (six books, nine journal articles, and three book chapters) that we identified as examples of homegrown theory based on the above criteria, and obtained their citation scores through the Web of Science, Cited Reference Search to assess their level of global recognition. The sample was established using a form of chain-referral technique, i.e. going through reference lists of works on the state of IR in different parts of the world and then checking individual studies to see whether they fit our criteria. The sample is by no means exhaustive but heuristically valuable. On average, the works in our sample are cited 12.4 times in the first five-year period after publication. The highest record is Cardoso and Faletto’s Dependency and Development in Latin America, which had 91 citations in the first five years. Comparing this to 5-year citation scores of, for example, Alexander Wendt’s Social Theory of International Politics or Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics, it might appear that homegrown theories do not fare too badly. However, there is very wide discrepancy within our sample, since four of the homegrown theories we found were not cited at all within the first five-year period and all but two of the others received fewer than 15 citations over five years. Such lack of recognition is a major impediment for theoretical enrichment of the discipline. An emergent theory should be applied, and confirmed or disconfirmed by other researchers, so that it undergoes continuous refinement and development. This makes theory building a collective exercise. Without recognition, the development of any emergent theory is hindered.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The next section introduces the proposed definition of homegrown theory and puts forward a typology. The subsequent three sections assess each type’s potential for global acceptance and further development by relying on an analysis of citations they receive. The article concludes by considering a number of critical factors in opening up space for different voices in the world of IR.

2. What is Homegrown Theory?

What distinguishes homegrown theories from mainstream theories is their origination from a geo-cultural standpoint, whether this be at the stage of concept formation or at the stage of inference. This standpoint however, marks the background of the ideas, not the theorists: National conceptualizations of IR are not the same as indigenous conceptualizations of international relations. The national identity of a group of closely collaborating non-Western scholars, or research by non-Westerners, is sometimes related to, but not the same as the identity of the “theory.” Phrases such as ‘Chinese School’, ‘Indian School’, or ‘Russian School’, cannot constitute homegrown theories in their own right if they refer exclusively to the community of scholars who work or live in these countries or are of these nationalities. It is only if such labels refer to those works which rely on practices, customs and phrases distinctively prevalent among the respective societies, that they become homegrown theories. An example is the English School, which does not refer to English-born scholars, but to the approach characterized by Britain’s experience and diplomatic practice, or the Copenhagen school, which does not comprise only Danish IR scholars, or those affiliated with the Copenhagen Peace Research Institute, but rather is made up of those sharing a philosophical and a normative concern on limiting state monopoly on defining security. A crucial step then is to identify where to look for the identity of theory.

There are basically two places to look for a theory’s “homegrownness”: the concepts can be homegrown, if they were specifically built by relying on a geo-culturally specific standpoint (whether it be a culture, civilization, religion, customs or traditions); and/or the theory can be inferentially homegrown, if the data used in the inference come from observation of geo-culturally specific phenomena, provided that such data are used for building or altering theories, not for testing them. Theorists either build on a local philosophical standpoint in their production of novel concepts and/or particularly draw their data from the part of the world they experience to invent new concepts or alter existing ones.

From these distinctions, three groups of theories emerge. Some scholars build on works by local thinkers, writers or scholars from different disciplines, and use their concepts with an IR outlook. Since most of them have indigenous intellectual and/or philosophical approaches as their starting point, we call them referential homegrown theories. A second group of scholars transforms mainstream Western ideas or concepts in such a manner that they reflect indigenous meanings attached to them by particular societies. These can be called homegrown alterations, with the level and type of alteration differing from one theory to another. Finally, some theorists develop original concepts out of geo-culturally specific experience and commonly used idioms of daily life, and use them in an IRT framework. Since they do not borrow from any pre-existing conceptualization either in the core or in the periphery, we call these authentic homegrown theories. The following sections address each type of homegrown theory individually and assess their prospects for recognition by the global IR disciplinary community.

2.1.Referential homegrown theory building

Referential homegrown theories are what come to mind first in thinking about homegrown theories. In this type of theory building, a homegrown thinker’s ideas or concepts of an indigenous culture, religion, civilization, etc. are used as a reference point to make inferences about observed phenomena. Thinkers such as Kautilya, Xun Zi and Ibn Khaldun, or cultures such as Hinduism, Confucianism, Buddhism or Islam, are examples. Usually the observed phenomena come from within the same geo-cultural sphere, rather than the ideas or concepts being applied to elsewhere. In other words, a non-Western standpoint is used both in concept formation and inference. Referential homegrown theories investigate empirical implications of homegrown ideas -particular cultures and thinkers-, and empirically and/or conceptually engage with these thinkers and cultures. As such, they move beyond mere suggestions of relevance of for IRT. Generally, referential homegrown theories redefine ideas of a homegrown thinker/culture in order to make homegrown ideas more accessible to a wider audience and more relevant for studying contemporary phenomena. Thus, they are instrumental in incorporating non-core ontologies into global IR.

There are a few attempts in which Xun Zi’s thought are considered as a source for understanding and explaining Chinese foreign policy behavior. In particular his thoughts on types of great powers and international order have inspired frameworks to explicate China’s “peaceful rise”. Xuetong redefines power in line with Xun Zi’s ideas to account for China’s “peaceful” rise. He particularly refers to Xun Zi’s Five Ordinance System, which is a hierarchy of power between nations that are under the rule of the emperor. The obligations of nations are based on their geographical proximity to the emperor and their individual power status. More distant and less powerful nations have fewer responsibilities, whereas closer and more powerful nations take on more responsibilities. Such redefinition of power that comes with higher responsibility, as well as Xun Zi’s renunciation of power as solely based on military strength, helps to explain why China’s accumulation of power has not led to conflictual balancing behavior.

Like China, India is also very rich in sources for homegrown conceptualizations. Three Indian perspectives on world order stand out: Nehruvian internationalism, Gandhian cosmopolitanism, and political Hinduism or Hindutva. Bajpai argues that Nehruvian internationalism is very similar to a Westphalian conception of order, yet it is differentiated by non-alignment. While Nehruvianism is not naïve about the use of force in international relations, “Jawaharlal Nehru rejected power-politics and the Western concept of maintaining security and international order through balance of power”. Therefore, non-alignment was both a principle of exercising autonomy in foreign affairs, and an ‘order-building’ instrument through which a ‘third’ area of peace outside the two power blocs was to be created to secure the establishment of a just and equitable world order. Behera argues that aside from its policy implications, “non-alignment was never accorded status or recognition as a ‘systemic’ IRT because it did not suit the interests of the powers that be”.

Gandhian cosmopolitanism emphasized non-violence (ahimsa) and presented a world order in which the rights of individuals, emancipation, and freedom are prioritized. In Gandhian thought, nation-state and nationalism were only instruments to ensure human liberation from imperial powers, and states should be radically decentralized bodies. The international system was important to the extent that it gave way to a world order, where small, autonomous groups of people interact on the basis of non-violence, truth power and economic equity. The Gandhian conception of world order was ontologically original in that it placed small communities as the primary actors of world politics. Inspired by Gandhi’s focus on non-violence, Galtung redefined peace as the absence of structural violence, and proposed a theory of conflict transformation through non-violent means. Galtung’s theory of structural violence was widely recognized, as he was regarded as the founder of Peace Studies. He also established the Peace Research Institute in Oslo (PRIO) and published the Journal of Peace Research. Although his inspiration by Gandhi was evident and self-proclaimed, it was somehow downplayed and in his later years, when Galtung focused more on peace activism, his impact in the scholarly community waned. This was partly because his wide adoption of Gandhi’s philosophy was alien to academics and researchers, as what he proposed “move[d] too far outside the usual interpretations” into what was no longer deemed peace research.

The peace research community’s wider attitude toward Galtung’s later work is illustrative of the first major risk associated with referential homegrown theories. If homegrown ideas are used in their original form, and redefinition of concepts is either non-existent or minimal, the resulting homegrown theory becomes insular. Although, referential homegrown theories appear to be the most common form of homegrown theorizing, (10 out of 19 in our sample are referential homegrown theories), and a few prominent scholars have in fact engaged in indigenous thinking, they do not do particularly well in terms of citation compared to other works in our sample. On average, referential homegrown theories have 7.9 citations in the first five years--below the overall average of 12.4. This lower citation rate may be because even if the resulting homegrown theory is original, its empirical implications may remain vague to non-indigenous researchers, which results in a diminished understanding of the theory’s potential to be applicable elsewhere. Another explanation may be the rather exclusionary nature of some of these conceptualizations. For example, Hindu nationalism, or Hindutva presupposes a regional hierarchy of civilizations, in which Hindu civilization occupies the first place among other civilizations. Based on its implications, Hindutva was deemed as a form of Indian fascism. At other times, theories maybe evaluated on the grounds of their practical consequences, i.e. the effectiveness that they hold for determining successful policy, as opposed to their explanatory power. For example, Nehru disregarded the ideas of Gandhi, which he found dangerous to the sovereignty and security of the nascent Indian state. Therefore, even when including rich tradition and innovative practice, referential homegrown theorizing attempts may not realize their full potential in terms of global reception, if they remain insular and largely prescriptive.

The second major risk associated with referential homegrown theories is the opposite of insularity: assimilation by mainstream theories. In these cases, homegrown concepts are redefined in a way that the resulting explanation is subsumed under a mainstream theory. When theorists fall short of assessing the empirical implications of referential homegrown ideas independently from preconceived paradigmatic lenses, homegrown concepts are “translated” in a way to correspond to one or more terms in current international relations lexicon. Such “translation” by subsuming the homegrown concept, usually serves as a confirmation of mainstream approaches.

Assimilation with respect to homegrown philosophers/philosophies is most often done through comparing homegrown ideas to those of “fathers of political theory,” and considering them as versions of mainstream paradigms. For example, Hassan points out 67 thinkers ranging from Herakleitos to Sartre whose ideas have been compared with or likened to those of the 14th century North African scholar, Ibn Khaldun. In international relations, he is alternatively depicted as a realist, postmodernist, or historical materialist. His ideas on group unity, asabiyah, have also been likened to constructivist accounts of identity.

Some of the works inspired by Indian philosopher Kautilya, who was regarded as an “Indian Machiavelli,” are also examples of assimilation. For example, Modelski asks whether Kautilya’s state system (mandala) was one of international order, where some sort of mutual understanding prevails. He argues that Kautilya’s system of states does not resemble an international order, but an anarchy, which is remedied by relative stability in the domestic sphere. Uzzaman refers to Kautilya’s thinking to explain India’s contemporary foreign policy and argues that Indian strategic culture espouses a “Kautilyan brand of realism”.

While the above examples of assimilations border on anachronism, other forms of assimilation are less direct: scholars incorporate homegrown philosophers’ inferences as empirical findings and make use of them to support their own (mainstream) conceptualizations. Gilpin, focusing on the relationship between physical environment and social life, is inspired by Khaldun’s explanation of the rise of the Islamic empire. Ibn Khaldun argued that the desert operated like the sea for Arabs and eased the empire’s expansion. Gilpin also uses Khaldunian insights on the relationship between internal composition of a state and its propensity to expand, as well as its decline because of corruption and luxury. Similarly, Deudney refers to Ibn Khaldun as one of the sources of his conceptualization of environment and its consequences on social and political life. Strange refers to Ibn Khaldun’s empirical findings, while Cox and Pasha refer to Khaldun as a potential source for conceptualization of change and world order in international relations.

Referential theories are easily identifiable as “homegrown” because they openly refer to a non-Western source of knowledge. Their level of acceptance by the global discipline might vary, however, depending on the acceptability of their policy implications on the one hand, and the theorist’s effort to articulate the novelty it brings when understanding and explaining contemporary phenomena. Insularity is particularly likely if the homegrown theory is applied to the same geo-cultural sphere from which it originates and can be overcome by applying it to other geo-cultural spheres. Assimilation is also unfruitful especially when it is anachronistic, e.g. treating Kautilya’s ideas as if he had written in a time where “realism” or “international order” meant the same as they do today. Anachronistic assimilation does not introduce novelty and basically fails to achieve anything more than just informing the reader that ‘an indigenous/non-Western thinker has thought similar ideas before.’ In our sample, examples of this type of work, i.e. work focusing on conceptual correspondences, were cited just once at most. This is not very surprising as they offer little guidance as to how those concepts would be applied to today’s affairs. The non-anachronistic form, i.e. introducing old works as new empirical evidence for modern IR theories, are more scientifically fruitful as they increase the travelling ability of mainstream concepts not only across places but also time. Yet it is an equally deficient strategy in terms of homegrown theory building, because the indigenous thinkers’ ideas are used to confirm or support an already existing theory, without any alteration. Cox’s two different pieces on Khaldun receive four citations each, while Pasha’s article is not cited at all.

2.2.Alterative homegrown theories

Alterative homegrown theories are built by restructuring mainstream theories based on evidence from indigenous experiences. It can be done in two ways: either different definitions for mainstream concepts are suggested or they are applied in a different level of analysis. Unlike referential theories, relying on local evidence is a requisite characteristic for alterative theories to be called homegrown. The resulting theory offers novel insights, but since it alters an extant mainstream theory, alterative homegrown theories are corrective, rather than innovative theories.

A rather globally acknowledged example of alterative homegrown theories is world-systems theory. Wallerstein extended Marx’s depiction of class and division of labor, and applied it on a global level. World-systems theorists’ innovation consists of having world-systems as the unit of analysis, not the states, since they argue that the agents in the world-system are not confined to any state’s borders. Crucial to this innovation is their use of evidence about a wide geographical area to account for the historical rise of the West, and continuing poverty of the most non-Western societies. Luxembourg’s earlier work on Turkey, Russia, India, China and North Africa as well as Wallerstein’s own work on Africa, provided the multiregional empirical background. While Wallerstein’s work was mostly qualitative, other world-system researchers also incorporated quantitative data to show worldwide patterns.

World-systems analysis’ reception is quite wide. Although we only included in our sample Wallerstein and Hopkins, a work that was cited 13 times in the first five years of its publication, Wallerstein and his colleagues subsequently produced a substantial number of works based on the theory, which augmented its recognition. Another factor in bolstering its reception was its institutionalization in distinguished universities and research centers in North America. Although the theory was inferentially homegrown (devised based on inferences from a non-Western experience of capitalism) most of the theorists were Western, and were linked to an extensive network in the core. Further factors might have been the familiarity of the global discipline with Marxist concepts, and the wide use of quantitative data, at a time when positivism was popular. Lastly, World-systems theory has strong connections to the disciplines of history and economy, and was able therefore to generate appeal in a wide range of disciplines.

Another attempt to apply mainstream concepts in other levels of analysis is Cai Tuo’s work on global governance. Cai defines global governance as a cooperation of official and non-official agents over a global problem within the borders of a country, i.e. transnational cooperation on national territory. This definition is inspired by conditions prevalent in developing countries: first, civil society is usually too weak to project its influence transnationally; second, there is a general distrust towards “non-territorial politics and globalism”, and finally there is a preference for dealing with global problems through established intergovernmental institutions and mechanisms. Therefore, civil society takes part in transnational networks only when the global problem in question is addressed locally with involvement of the local government. Transnational cooperation is a learning mechanism for both civil society and domestic government, where a top-down understanding of management is slowly giving way to a more open one.

Cai’s correction to the global governance literature is to apply a supposedly global level concept at the domestic level, which reveals the discrepancy between the developing societies and developed societies in terms of both attitude and ability. His analysis also offers practical guidance as to the improvement of civil society and argues that involvement of host state institutions may serve to improving global consciousness and global values.

Similarly, Qin Yaqing finds fault in the mainstream global governance literature in explaining East Asian governance practice. Most theories of governance rely on rule-based governance, with the underlying assumption that individuals are rational, cost-calculating actors with exogenous self-interests. But in East Asian communitarian societies, he argues, the essence of governance is relational, and it highlights morality, and trust, all of which are drawn from Confucian philosophy. While rule-based governance takes tangible results as the objective, relational governance emphasizes process, i.e. maintaining a relationship which makes participation, strengthening of ties, and developing a shared understanding possible. Consequently, he argues that judging ASEAN and APEC as ineffective in comparison to the EU or NATO is misleading, since the merit of the former may not be in achieving tangible results, but in maintaining continuous dialogue and negotiation.

Qin Yaqing is not the first to introduce a “relational” and “processual” ontology to the study of IR, but his conceptualization differs from mainstream theories in terms of his understanding of trust as a genuine social norm, rather than as another cost-reducing mechanism. Moreover, he reconceptualizes “relational” in the domain of governance. Despite his emphasis on Confucian values, he does not directly refer to Confucius in his concepts or inferences, but he highlights the distinctive experience of East Asian subjects, whose daily life is infused with Confucianism.

Compared to the above, some other attempts involving a less substantive correction, i.e. homegrown improvements, redirect the application range of mainstream theories, by offering alternative operationalizations. For example, late socialist and then post-socialist Russian scholars incorporated a few Western-derived concepts, which gave way to the development of a “national liberal school” of IR in Russia. The school combines “nationalism” and “liberalism”, terms which acquire a different meaning in the Russian context than that employed by Western theorists. For example, they point to the importance of international institutions and a non-unipolar world as a means to achieve peace, they emphasize the risks of globalization, while not denying the opportunities associated, and argue that the democratization process must reflect local conditions.

In a similar vein, Kuznetsov builds on Toynbee’s and more recently Huntington’s theory of “clash of civilizations,” in his theory of “grammatological geopolitics”. While Huntington’s theory proposes that the potential zones of conflict run along the fault lines of nine largely denominational civilizations, Kuznetsov’s grammatological geopolitics defines civilizations in terms of the alphabets the nations use and argues that a more accurate prediction of conflicts can be attained by the resulting fault lines. In addition to Huntington’s, he identifies seven more, “smaller” sub-cultures: Greek, Hebrew, Armenian, Georgian, Mongolian, Korean and Ethiopian. These subcultures are more prone to conflicts than are broader civilizations because of their rather fast developmental potential. As evidence, he particularly refers to conflicts in and around the post-Soviet states, such as between Serbia (Cyrillic) and Croatia (Latin) in 1991-1995, as well as Georgia’s (Georgian) war with Russia (Cyrillic) in 2008, South Ossetia (Cyrillic) in 1991-1992, 2004, and 2008, and with Abkhazia (Cyrillic) in 1992-1993, 1998 and 2008.

Homegrown alterations of mainstream theories may reflect a) interdisciplinary approaches, b) sensitivity to changing meanings of concepts in different settings, and c) experimentation with respect to level of analysis. Through these strategies, the resultant theorizing becomes more than a simple application of the existing theory, and acquires a certain degree of originality. Other forms of engaging with mainstream concepts are less substantial, often employing only one of the above strategies. These homegrown improvements of mainstream theories are important in advancing the “traveling ability” of mainstream concepts or point out their limitations in doing so. In consequence, they are valuable for expanding the application range, i.e. “globalness”, of mainstream International Relations. Although they are hypothetically more advantageous in terms of reception, as other scholars already have familiarity with the concepts, in actuality they are the least cited form of homegrown theorizing in our sample. On average, each alterative homegrown theory work is cited six times in the first five years, which is only half of the overall average. One particular reason may be their inherent position on “the fringes” of mainstream theory, rather than being “out” of mainstream theory: taking a corrective stance by pointing out the shortcomings of an established paradigm, may be regarded as more threatening to hegemony than either referential or authentic homegrown theories. This also highlights the tremendous difficulty faced by periphery scholars when they attempt to challenge the core theories: they are not refuted, but are simply ignored.

2.3. Authentic homegrown theory building

Authentic homegrown theory building essentially relies on scrutinizing available or newly collected data and focusing on the incongruencies between what has been observed and what has been expected based on extant conceptualizations. Authentic homegrown theory building begins with putting forward empirical puzzles and coming up with original concepts to explicate these puzzles. Authentic concepts are coined with little or no reference to either homegrown ideas or mainstream theories.

Focusing on empirical puzzles for theory development is a common strategy among inductively oriented researchers. Consequently, systematic collection and/or analysis of (usually a large magnitude of) data is tremendously important to not only homegrown, but any authentic theory building. Since authentic homegrown concepts are not redefined or refined forms of indigenous conceptualizations, what makes them homegrown is the origin of the data used while making inferences. In other words, authentic homegrown theory is not conceptually, but inferentially homegrown.

One example of authentic homegrown theory building out of the periphery comes from the latest Chinese efforts to analyze China-US bilateral relations from 1950 onwards using event data. Yan Xuetong tries to explain the “sudden deteriorations followed by rapid recoveries [which] have been the norm in China–US relations since the 1990s”. He proposes that fluctuating relations, characterized by “short-term improvements in China–US relations that have followed each short-term dip” are neither attributable to rising nationalism in China nor to Chinese overconfidence built upon China’s fast economic growth, but rather to the discrepancy between heightened expectations of the two sides and the actual policy inclinations derived by their interests. He states that the good will by both sides actually worsens the balance in their bilateral relations, because it impedes their ability to pinpoint realistic policies based on their interests. It actually gives way to the establishment of a “superficial friendship” in which both countries imagine they have more common interests than they actually have. The resulting inconsistency leads to instability.

Xuetong extends his argumentation by building a typology of bilateral interests with respect to different sectors of China-US relations. While in security matters, US and Chinese interests are mostly “mutually unfavourable,” in economy and culture, they have more mutually favorable interests, so much so that he calls them “cultural friends”.

Observing different fluctuation patterns in different time periods, Xuetong’s theory explains them with the (in)congruence between expectations and interests. At the same time, he addresses the contemporary Chinese problematique: finding peaceful yet assertive ways to engage with the outside world. Accordingly, his theory can also be regarded as prescriptive; too much optimism, i.e. heightened expectations with respect to US-Chinese relations, can actually impede rather than boost stability.

Another example of authentic homegrown theory building out of the periphery is Latin American dependency theory, which is inferred from the Latin American experience in development and international trade in the 1950s. It also originates from an empirical puzzle: In contrast to David Ricardo’s thesis that free trade would benefit both parties because of the comparative advantage, terms of trade for underdeveloped countries relative to the developed countries had deteriorated over time. Raul Prebisch, an Argentinian economist, argued that there were “declining terms of trade” for Third World states, because peripheral nations had to export more of their primary goods to get the same value of industrial exports. Through this system, all of the benefits of technology and international trade transfer to the core states.

Dependency theorists integrated Prebisch’s thesis with their observations regarding global relations of production in Latin America. Contra modernization theory, they argued that looking at domestic determinants of economic growth and development is not sufficient to understand the patterns of (under)development. An international outlook, which takes into account historical and sociological variables, along with interactions between and across domestic and international realms is also needed.

For Latin American structuralists Fernando H. Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, dependency and development were not mutually exclusive: dependency and autonomy were two ends of a political continuum, as development and underdevelopment were two ends of the economic continuum. They argued that the local political elites in peripheral states have structured their domestic rule on a coalition of internal interests favorable to the international economic structure. Therefore, international capitalist structure, by itself, does not lead to a single form of dependency; it is rather the sociological consequences and the subsequent alliances which shape the dependent status of the South.

Although originated in Latin America, structuralist dependency theory could be applied to a wider scope of countries, from economically developed ones in East Asia to underdeveloped countries in Africa. The emphasis on alliances and struggles within and across national borders makes the theory more historically nuanced and more conducive to social change albeit at the expense of predictive power.

A final example of authentic homegrown theorizing is from South Africa. Geldenhuys focuses on the South African experience of being an isolated state for four decades, and puts forward a descriptive theory of isolation. Analytically differentiating isolation from other forms of estrangement, such as short-term alienation, obscurity of a state (being ignored), or armed isolation during war, he defines isolation as either a long term, voluntary and deliberate policy by a state (self-isolation) or a deliberate policy by other states (enforced isolation) to diminish one’s level of international interaction. He gives a detailed list and description of 30 indicators of isolation and investigates questions pertaining to targets and implementers of isolation, its means, causes, objectives and effects. His framework is original in pointing out a rather understudied phenomenon in international relations, but one which dominated South African domestic and international politics for decades. On the other hand, Geldenhuys’ theory of isolation is mostly a descriptive rather than explanatory theory.

Both Xuetong and the dependency theorists pointed out patterns in the data, unforeseen or under-explained by the existing theories. Similarly, Geldenhuys’ operationalization of isolation required extensive data on several spheres of international interaction. Authentic homegrown theories seem to rely on extensive collections of data, either to reveal empirical puzzles, or to describe a situation. This is probably due to the lack of a conceptual reference point to justify their arguments. While theorists in the core can write purely theoretical pieces with little or no reference to systematically collected data, a similar option appears untenable to homegrown theorists, since it would jeopardize their acceptance by the global discipline. Such data collection, however, requires substantial time and effort, which might be one of the reasons authentic homegrown theories are rare to find. At the same time though, extensive data collection seems to augment their citation scores. The average citation score for the above three examples is 38, and even when Cardoso and Faletto, 1979 is removed as an outlier, the average score is 11.5.

3. Conclusion

Homegrown theories are by definition local, i.e. attached to a particular geo-cultural sphere. A theory, on the other hand, is presumably universal, applicable to classes of phenomena that can be found anywhere, anytime. Accordingly, claims for homegrown theorizing are often rebuffed or downplayed on the basis of their supposed parochialism or exceptionalism. Despite the claim for universality however, mainstream IR theories are also parochial, a phenomenon that became increasingly evident over the years since Hoffmann’s declaration of IR as an American social science. If all of the supposedly ‘universal’ theories are parochial as suggested, then it would be unfair to dismiss a self-admittedly homegrown theory on the basis of parochialism. It would rather be more accurate to state that all theorizing is homegrown, with the potential for universal recognition, if not application. Such a stance can pave the way forward to a more inclusive discipline. As one scholar puts it, it might indeed be the only way for International Relations to be more inclusive and hence truly “international”.

Our review suggests that despite the inequality in the social and political sphere, there is great potential in terms of periphery-based, homegrown IRT. There are voices out of the larger world, but they are not incorporated successfully into larger literature. The supposed universalism of any theory depends on its acceptance by the wider community of scholars. All the major theories of today were once a homegrown theory, and the material and discursive power of these theories came from the power of the object they studied. As these theories grew into becoming universal, the discursive sphere was shut down to outsiders to keep the hegemony intact. Their monopoly on the scholarly imaginations of international relations has become the major obstacle to a true globalization of IR. The power of actors (whether they are states, nations, groups, civilizations or even theorists) is still the determining factor in identifying whose voices will be globally heard and integrated into the global scientific discipline. Structural and institutional factors, such as discrepancies in material capabilities, network structures and publication opportunities between the core and the periphery have a huge effect on whose theory will be popular. The theories and conceptualizations of international relations of an international system under Chinese, Russian or Indian hegemony would greatly differ from the current ones in ontology and epistemology.

A closer look at the types of publications, suggests that there remains a major packaging, production, and marketing problem, which inhibits the contribution homegrown theorizing might make to the wider discipline. On average, from our sample, books presenting examples of some form of homegrown theorizing are cited 35 times, articles 4.8 times, and book chapters 1.3 times. Clearly, publishing books instead of articles appears to pose an advantage for homegrown theorists. The prestige of the publishing house and its range of distribution network may facilitate its recognition. Additionally, the depth of elaboration permitted by the relative length of a whole book might be instrumental in augmenting an idea’s reception. On the other hand, compared to articles, publishing books, especially by a well-known publishing house, requires a higher level of pre-existing recognition by the scholar. Therefore the books may be cited more because the authors of those books are already well-known and hence already have wider access—Cardoso, Galtung and Xuetong are already well-known figures. Nevertheless, comparing citations to specific book chapters to citations for the whole book, suggests an interesting pattern. Order and Justice in International Relations is cited 29 times in total, but only one of these is to Bajpai’s chapter. Most of the citations are to chapters written either by the editors, or to the chapter that focuses on Europe. Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics is cited 548 times, but only 12 of them are to Cox’s piece on Ibn-Khaldun. Again the most citations in this volume are directly to the editors’ chapters or to works on the Western international system from a critical perspective. Similarly, Innovation and Transformation in International Studies is cited 36 times, none of which is to Pasha’s chapter. The most cited chapter in the volume is that of Stephen Gill’s piece on Karl Polanyi. Therefore, even when the material obstacles to wider access are surmounted, or even when the articles are published by well-known and elsewhere abundantly cited scholars, homegrown conceptualizations’ reception is relatively low.

Beyond the above factors that are exogenous to the process of theory building, a few observations can be made about the substantial differences between the theories themselves, which may account for how these differences reflect on their acceptance. The foremost quality of a new theory is that it can be understood and applied by other researchers. Therefore, insularity and vagueness are both fatal to homegrown theories. Accordingly, the concepts used should be adequately defined and clarified. As Lynham points out, “an important function and characteristic of theory building is to make these explanations and understandings of how the world is and works explicit and, by so doing, to make transferable, informed knowledge for improved understanding and action in the world tacit rather than implicit”. If theorists fall short of transmitting to the mind of the reader, how and where one can test the suggested theory, or how one can infer from the empirical observations that the proposed mechanism is at work, then the theory will not be engaged. Original concepts are good, but those whose meaning is too blurry for others to understand will remain unproductive. If nobody else is able to apply the concept, then the theory is doomed to isolation, and its development will halt. In particular, a poor clarification of concepts used in Referential Homegrown Theories may limit their transferability to the people cognizant of the referent culture or ideas. Limited transferability may confine such theories to discussions within communities of culturally homogenous scholars, which will deny the global IR community the fundamental benefit of referential homegrown theories, i.e. incorporation of non-core ontologies.

Insularity and policy dependence inhibit reception; assimilation and anachronism threaten originality and diversity. Comparisons across thinkers, or studies on a non-Western thinker, may be fruitful in familiarizing the global discipline with periphery theorists’ ideas, but from a theory building purpose, assessing and testing empirical implications of their ideas independently from preconceived paradigmatic lenses, is paramount. In other words, the concepts should not simply be “translated,” a practice which usually serves as an implicit confirmation of mainstream approaches. Deriving implications out of those ideas, and testing them against the data is what makes any theory stronger.

Finally, a closer look at the most cited of the theories explored here, reveals that the most efficient way of building both original and recognized theories appears to be through systematic collection of data. Xuetong relied on quantitative data on US-China bilateral relations, dependency theorists based their theoretical innovation on foreign trade data, and Geldenhuys made an extensive collection of qualitative data on levels of international interaction. It is impossible to ignore the irony in this, as empirical work is often considered in dichotomous terms with theory, and those who are empirically oriented, i.e. “native informants,” “area specialists,” or “historians” are seen as “non-theorists.” Such a starting perspective is a major obstacle in overcoming the broader hegemonic division of labor. Better theories cannot be built out of philosophical and meta-theoretical discussions, they can only be built through hands-on empirical work. Still better theories can only be built through the hands-on work of a wider, global scholarly community.

Appendix