1.Introduction

In the last two decades, peace efforts and endeavours to deal with conflicts have been billed as either a “process of national unity,” a “national peace process,” or a “national reconciliation process.” In addition to national reconciliation initiatives, there has also been a global outburst in practical variations, such as UN peace operations (i.e. post-conflict peace-building operations), ad hoc international criminal tribunals, truth commissions, negotiations, and traditional rituals of integration, which are some of the array of practices employed to validate peace. Our era, thus, might be called “the age of peace-building”; even though we don’t live in an age of peace.

Despite an abundance of theoretical and methodological peace efforts, the contemporary world is not as peaceful as it should be, since large-scale conflicts persist in Afghanistan, Syria, Nigeria, Congo, Iraq, and several other locales. The old paradigm of industrial inter-state war no longer exists; the new trend is “war amongst the people,” and the most pressing troubles are violent acts that human beings commit against each other.There are two implications of the “war amongst the people”: first, in intra-state conflict, nearly 80% of the casualties are civilians rather than professional armies or militia, and second, after peace, former enemies, perpetrators, and victims must continue living side by side. In these circumstances, without a well-thought out and implemented reconciliation, peace can only be in a negative form, and the resumption of hostilities is imminent. This fact makes reconciliation, rather than peace, extremely important, since the former provides alternative platforms to prevent the re-emergence of conflict by bringing parties under the framework of shared values. Notably, national reconciliation has emerged as a societal conflict resolution strategy that seeks to transform attitudes through reparations, truth-telling, and healing amongst former adversaries. Although Lederach prefers to use “comprehensive” rather than “national” for this approach, national, in this sense, infers the participation of political leaders or groups whose influence over a given nation-state is accepted to shift the society ravaged by various forms of internal violence toward a non-violent structure.To support this paper’s argument of a leader’s strategic function in national reconciliation (as per Ratil Alfonsin in Argentina, Patricio Aylwin in Chile, and Aniceto Longuinhos Guterres Lopes in East Timor), Nelson Mandela’s efforts as a forerunner in South Africa will be identified.

The theoretical framework of this article is based on Galtung’s Conflict Triangle. Since national reconciliation is the formulation or demonstration of either the attitude or behaviour of national political leaders, throughout the article, Mandela’s reconciliation-oriented efforts (from 1989 to 1999) will be identified by two indicators: 1) normative statements (measuring attitudes) and 2) symbolic and judicial acts (measuring behaviours).

This article is organized in four parts. The first contains an extensive conceptual analysis of reconciliation, of which definitions and types are identified. To this extent, a broad understanding of the term reconciliation is explained. The next part provides the article’s theoretical background, that is, the “Conflict Triangle” developed by Johan Galtung on the bases of “conflict attitude (A),” “conflict behaviours (B),” and “contradictions, [the] conflict issue itself(C).”Galtung’s analytical framework is an applicable method for structuring the analysis of national reconciliation in this study. The third rubric of the article handles Mandela’s reconciliation-oriented characters (forgiveness, removing vindictiveness, and empathetic capacities), which favourably affected South Africa’s national reconciliation process. The final part of the article analyses Mandela’s reconciliation initiatives through “Normative Statements,” “Symbolic Acts,” and “Judicial Acts” to illustrate the tangible implications of his work toward intergroup coexistence. The importance of Mandela’s overall implications is supported by three essential facts that made his reconciliation-oriented initiatives more strategic and durable: South Africa’s historical background, the heterogeneous structure of South African society, and the potential power of the white community in South Africa.

2. Reconciliation as Conflict Resolution: A Conceptual Scaffold

Although the background of reconciliation goes back as far as the eighteenth century, the term’s involvement in political studies and international relations by Peace Theory has only recently gained significance. For decades, political thinkers have considered the term an irrelevant concept due to its religious connotation. After the Cold War, however, literature studies on reconciliation notably increased, which helped to disassociate the term from a religious context, but much more critical discussion is needed. For instance, Susan Dwyer’s piece on Reconciliation for Realists, in contrast to religious affiliation, provides an image that is wholly distinct from the religious standpoint.

In the contemporary perception, reconciliation is a complex, vague, contested, and often slippery term with many possible meanings made up of various components that all play apart;as a result there is little agreement on the term’s definition. This situation is largely because reconciliation is considered both a goal ‒ something to achieve ‒ and a process ‒ a means to achieve that goal. The goal of reconciliation is to create a common future, a permanent solution, perhaps even an ideal state to hope for. But the process, on the other hand, is very much a precursor, a way of dealing with how things are. Building a reconciliation process develops the means to work effectively and practically to access the goals. In contrast, however, Rosoux asserts that reconciliation is a process rather than a goal and that this process is not linear but a continuously evolving relationship between perpetrators and victims. Similarly, Goodman says reconciliation is an incremental and nonlinear process that involves replacing fear with non-violent coexistence. To widen the discussion, Michael Hardimon’s book, Hegel’s philosophy of reconciliation, is noteworthy. According to Hegel, reconciliation as it is ordinarily used, is systematically ambiguous between the process of reconciliation and the state that is its results. Further, reconciliation means different things to different people in different levels of conflict, such as between wife and husband, offender and victim, or nations and communities.

J. Paul Lederach, who has developed one of the rare theoretical conceptualisations of reconciliation, suggests that the “peacemaking paradigm of reconciliation involves the creation of social space where truth, justice, mercy and forgiveness are validated where justice and peace have kissed”. Even though the reconciliation process contains paradoxes and contradictions, Lederach writes most eloquently about it. He says reconciliation can be seen as dealing with three specific paradoxes. First, while reconciliation searches for the articulation of a long term and independent future, it provides an encounter between the open expressions of sorrowful past. Second, reconciliation ensures a platform for mercy and truth to meet, in which past suffering is explored for letting go in favour of a renewed relationship. Third, reconciliation requires a time to sustain peace and justice in which redressing the wrong is held together with the envisioning of a mutual, connected future.

On the other hand, Johan Galtung formulates reconciliation as Reconciliation = Closure + Healing. Closure means not reopening hostilities, and healing is used in the sense of being rehabilitated. In this vein, Danish peace researcher Jan Öberg writes: “reconciliation is synonymous with saying goodbye to revenge”. Sampson emphasizes that “reconciliation is synonymous with coexistence,” simply saying that reconciliation is “the absence of violence or a departure from violence.” Brounéus’ and Bloomfield’s remark that reconciliation is a societal process that consists of accepting past suffering, and while not necessarily loving them or forgiving the perpetrators), changing destructive behaviours and attitudes into constructive means by convincing society that we will all have better lives together than we have had separately.

The strength of this definition lies in the centrality of the following components: changes in emotion (mutual acknowledgment of suffering), attitude, and behaviour. From all of the definitions, we see that reconciliation is a societal, incremental, and non-linear process that involves mutual acknowledgment of past suffering and the changing of destructive attitudes and behaviour into constructive relationships. We do not necessarily become friends with those we disagree with, but we construct a relationship through and in a non-violent setting. Therefore, reconciliation can be delineated into three parts: emotions, attitudes, and behaviours, all of which involve reparations, truth-telling, and healing among former adversaries.

Looking at the varieties of reconciliation we see that the empirical research of reconciliation occurs on three levels: the individual level focuses on trauma and how victims experience participating in a truth-telling process for reconciliation; the social level focuses on how former conflicting parties perceive each other before, during, and after this process; and the national level focuses on how governments and rebel groups act during reconciliation. Simply put: national reconciliation represents the macro level, which includes the attitudes and behaviours of national political leaders (government and/or opposition) and those in power.

3. Galtung’s Triangle of Conflict

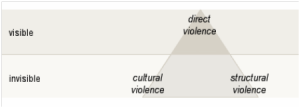

Peace is more than the absence of war, says Howard,so the ultimate goal of reconciliation is to maintain both negative and positive peace through creating newly defined social relations between the formerly oppressed and their oppressors. From this perspective, Johan Galtung developed a “Conflict Triangle.” Its three corners consist of the following: (A) conflict attitudes, (B) conflict behaviours, and (C) contradictions, [the] conflict issue itself. Accordingly, reconciliation urges a change in attitude and behaviour as well as being concerned about incompatibility. Galtung’s analytical framework therefore proves useful for structuring an analysis of national reconciliation.

In fact, the ABC conflict triangle model was originally aimed to operate in war situations, but over the years, it has been used to resolve other conflicts, such as family violence, racial discrimination, and human rights abuses, in addition to reconciliation. In general, the method deals with destructive or violent conflicts and reflects the normative aim of preventing, managing, limiting, and overcoming violence; in Galtung’s view, violence begins with cultural and structural repression.

Figure 1: Galtung’s Conflict Triangle

According to Galtung, there are various types of violence that could roughly be classified into three categories: the first category is cultural violence (or conflict attitudes‒ A), which involve assumptions, cognitions and emotions that one party may have about itself and the other, such as self-righteousness or superiority, and these factors represent the invisible part of the conflict. The second category is direct violence (or conflict behaviours ‒ B), which represents the visible category and contains mental, verbal, or physical insults and expressions put forth in a conflict, such as the actions, thoughts, and words demonstrated when a conflict occurs. The third category is structural violence (contradictions; the conflict issue itself ‒ C), which is the perceived incompatibility or clash between the goals of two or more parties that represents the invisible part of the Triangle. Contradiction causes violent attitudes and behaviours. Each angle of the triangle can serve as a gateway to peacefully influencing the conflict.Galtung emphasises attitudes and behaviours, which are identified by two indicators: measuring attitudes (normative and strategic policy statements) and measuring behaviours (symbolic and judicial acts). Therefore, in this paper, Galtung’s conflict triangle is applied to Mandela’s initiatives under the rubric of normative statements, symbolic acts, and judicial acts.

4. Reconciliation-oriented Leadership: Nelson Mandela’s Peace Characteristics

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. My ideal is a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunity. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and achieve, but, if need be, an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

Nelson Mandela, 1963

South Africa has made surprising strides in race relations, and Mandela can be credited with the lion’s share of that success. The name of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela is synonymous with South Africa’s liberation struggle, freedom, peace, and reconciliation. Without Mandela, South African history would have taken a completely different turn. After the collapse of apartheid in early 1990, the response to South Africa’s nation-building challenge was most visibly adopted through Mandela’s own mythology and became intertwined with that of the “new nation”.

Despite the prophetic name he had been given – Rolihlahla; “trouble-maker”‒Mandela became a person of integrity and sound principles, and a peace-making leader. His last quality is exceptionally rare in the world of politics. He also became a fighter for equal rights, describing himself as having a “stubborn sense of fairness,” where the terms inferior and superior did not exist for him. One of Mandela’s fundamental character traits is “unitive” leadership, which embraces all diversities. He moved from a self-focused responsibility (such as his own freedom) to a socially oriented responsibility (i.e., freedom for all), so he remarks that “my hunger for the freedom of my own people became the hunger for the freedom of all people, white and black.” He did not speak as a dissident representative of a minority view, but projected a national vision to the people of South Africa and the world at large. While in prison, he always used the word ‘We’ rather than ‘I,’ which is further proof of his dedication to his people. Although Mandela has several distinctive peace traits, for the purposes of this paper, we list three relating to the reconciliation process: forgiveness, dissolving vindictiveness, and empathetic capacities.

If forgiveness were applied as a distinction to Nelson Mandela it would seem that he was a man of forgiveness, says Shawn O’Fallon. However, forgiveness by itself is not an often-used term in Mandela’s writings and speeches. For instance, in his second autobiography and in nearly 1200 electronically collected speeches and interviews, there are just 19 examples of the uses of forgive or forgiveness. Due to the constructed nature of the boundaries around the term forgiveness, Mandela instead talks about the spirit of forgiveness. As is evident by Mandela’s symbolic acts, he himself was able to treat those that unjustly imprisoned him for 27 years with the spirit of forgiveness.

Due to South Africa’s historical background, forgiveness was needed as various emergent acts to achieve success in reconciliation. Racial conflict began with the first white settlers in 1652. When the National Party came to power in 1948, the apartheid regime was accepted as official state policy, although it had been de facto policy since 1910. Therefore, colour-based societal disintegration ideology was accommodated with several oppressive legislations which left deep-seated challenges to reconciliation. For oppressed blacks, the historical background caused an accumulated hatred with a strong drive for vengeance. This situation could have resulted in mass executions or a bloody civil war once the black community gained power. Therefore, Mandela’s great achievement was to transform that anger into peaceful and non-violent protest despite fierce opposition. Integrating isolated blacks into the new peaceful system, convincing them to live side by side with white minorities and building a colour-blind society could not have been achieved without the forgiveness-oriented character of Nelson Mandela.

The lack of outward vindictiveness toward adversaries is another characteristic of Mandela’s. Saths Cooper, who shared a cellblock with Mandela for five years, says:

Mandela was able to get on with every person he met...Despite having ideological disagreements, he was always able to maintain personal contact, it doesn’t matter if you differ, he is always polite. He never gets angry. All he will do is try to have the discussion as amicably as possible.

According to Stengel, who worked with Mandela on his autobiography, the latter’s great achievement as leader is his ability to show the smiling face of reconciliation rather than frowns of bitterness and lost opportunity.

Mandela also has an empathetic capacity, which helped him in his political efforts and makes him more likely forgive others. Tom Lodge, one of the respected historians who worked on Mandela’s life, says, “Mandela possesses a genuine capacity for empathy, to shift from one kind of social etiquette to another, an ability that indicates an unusually imaginative capacity for empathy.” Empathy became part of Mandela’s life philosophy; thus he believed that the Afrikaners had a right to be in South Africa, and never threatened to drive them from the country. He was able to understand how isolated whites were in the situation, and that they tended to know blacks only as servants. While applying the skill of empathy, he always sought mutual ground that united the nation in sharing anti-colonial Afrikaner/African identity.

In a nutshell, Mandela was an exceptionally motivated, philosophically pragmatic, and intellectually creative leader who exhibited the merits of gentleness, compassion, hospitality, openness to others and knowing that one’s life is closely bound to all other lives. Thus, he always spoke of ubuntu, an African concept of human brotherhood, mutual responsibility, and compassion, which infers that ‘a person is a person through other people.’ Consequently, Mandela’s reconciliation-oriented characters helped to transcend the anger, bitterness, and vindictiveness that existed between the white and black community.

4.1.Mandela’s reconciliation initiatives through normative statements

Normative statements made by those in power, representing measuring attitudes in Galtung’s conflict triangle, disclose the ambience and perception regarding the atmosphere for reconciliation. J. Paul Lederach emphasises the necessity of this category for setting the space to envision a commonly shared future.A general picture of society is painted through normative statements, yet no moral or ethical considerations are taken into account. In this regard, we analyse three of Mandela’s essential statements that had a watershed effect on national reconciliation.

The first statement occurred when Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990. South Africans and the world had been waiting for this iconic moment, to hear his vision for South Africa. Therefore, his first address to the crowd carried the codes of the new nation’s metaphor. The final part of his first speech was particularly significant:

We call on our white compatriots to join us in the shaping of a new South Africa. The freedom movement is a political home for you too....I wish to quote my own words during my trial in 1964.... ‘I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But, if need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.’

This speech sent a striking message to the white and black community to ensure that Africa belongs to all, irrespective of race, sex, ethnicity, and stature.

The second strategic discourse was made during the Hani crisis. In the early days of the 1994national election, the biggest threat to the country’s transition came with the assassination of Chris Hani on April 10, 1993. Hani was General Secretary of the South African Communist Party and considered to be Mandela’s successor. He was immensely popular, and his death was followed by riots in which70 people died. After the assassination, serious tensions led to fears among whites and blacks alike, so Mandela played a key role in calming the situation through a television broadcast:

Now is the time for all South Africans to stand together against those who, from any quarter, wish to destroy what Chris Hani gave his life for ‒ the freedom of us all. Now is the time for our white compatriots, from whom messages of condolence continue to pour in, to reach out with an understanding of the grievous loss to our nations.... This is a watershed moment for all of us, to every single South African black and white.

Thanks to Mandela’s appeal, the ensuing protest was peaceful and calm returned. The Chris Hani issue shows that no other single event in the reconciliation process provoked such a dramatic shift in the balance of power, proving how significant Mandela’s statement was. One of Mandela’s biographers notes that no other event revealed to the white community how significant Mandela was to their future security.

The third landmark statement was occurred in the aftermath of the first all-races election on April 27, 1994. At the time, the situation was quite dismal; the night before the election many supermarkets ran short of long-life milk and similar products as many whites prepared for war-like conditions.The Mandela-led African National Congress (ANC) won South Africa’s first democratic election, and in his inaugural address on May 10, 1994, Mandela made a remarkable speech:

The time for the healing of wounds has come, the moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come, and the time to build is upon us.... We know it well that none of us acting alone can achieve success. We must therefore act together as a united people, for national reconciliation, for nation-building, for the birth of a new world. Let freedom reign. We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity ‒ a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.

Mandela selected a truly cross-cultural cabinet, with white and black ministers, illustrating that the country belongs to all. Fifteen politicians who had served in the apartheid era were re-elected. De Klerk himself, the last head of state of the apartheid era, and who worked to end it, became one of Mandela’s deputy presidents.

4.2. Mandela’s reconciliation initiatives through symbolic acts

Symbolic acts accommodate measuring behaviours, and can be in the form of apologising, establishing a truth commission, introducing new national symbols or a flag that represent unity to create positive spirals of behaviour. Aware of the importance of such acts, the Mandela-led government introduced new symbols, notes and coins, and a new national flag and anthem. The anthem combined the popular African liberation song Nkosi Sikelel’i Africa (God Bless Africa) and parts of the old anthem Die Stem, and was a strategic implementation that reflected hope in a peaceful post-apartheid society.The merger of symbols was harmonised via several legal adaptations which illustrated a new national identity linked to reconciliation, non-racialism, rebirth, and unity.

Mandela also pursued an array of symbolic gestures that paved the way for the reconciliation process. He paid a visit to Percy Yutar, the prosecutor who had sent him to jail for 27 years, held a tea party with former (white) politicians, hosted a dinner party for the former commander of Robben Island (where Mandela was imprisoned for most of his sentence), and met with H.F. Verwoerd’s (prime minister of South Africa from 1958 to 1966) widow Betsie Verwoerd, and former president Botha.Despite fierce opposition in the ANC leadership towards Mandela’s unilateral symbolic acts, he believed in the significance of such initiatives for reconciliation. Mandela believed that given time, the Afrikaners would accept the new South Africa and make a significant contribution to the Rainbow Nation. These gestures had a tremendous impact on building national trust between parties.

Building reconciliation through sports has been in place for many years, and Mandela included some in his symbolic acts. In South Africa, soccer was perceived as black, cricket as white and English, and rugby as white and Afrikaans, therefore the sport’s influence on the country was beyond dispute. In June 1995, the South African rugby team, the Springboks, defeated New Zealand in Johannesburg in the World Cup. Hosting the World Cup presented an opportunity to demonstrate the government’s commitment to support a cause close to Afrikaners’ hearts and bring black and white together. For Mandela, it was the right place and moment to lead the country into a further reconciliation process, although many black leaders called on Mandela to boycott the games. In addition, South African rugby authorities were famously conservative and did not buy into Mandela’s strategy due to insufficient trust. Despite the unfavourable circumstances, Mandela attended the game wearing a Springbok rugby jersey and presented the winner’s trophy to the Springbok captain. His visits to players were well publicised, which opened a new page in national reconciliation. At the end of the game, the new national anthem was sung and the handshake between team captain Francois Pienaar and President Nelson Mandela was widely portrayed throughout South African society. Mandela’s intrepid action received wild applause from all circles of Afrikaner rugby fans, who started to chanting ‘Nel-son, Nel-son.’ After that, the white singer P.J. Powers wrote new lyrics echoing the official slogan, “One team, one country/Gathering together/One mind, one heart/Every creed, every colour/Once joined, never apart.”Inevitably, this action took the process of reconciliation into another dimension. Through Mandela’s symbolic acts, interaction between people of different races was transformed from alienation to an intended search for dialogue and contact, particularly amongst youngsters.

The social fabric of the country made Mandela’s symbolic behaviours that much more significant. South Africa’s complex history has bequeathed to the present day a rich ethnic, racial, linguistic and religious diversity. Nearly 79 percent of people classified themselves as black African (which includes ethnic groups such as Zulu, Xhosa, Basotho, Bapedi, Venda, Tswana, Swazi, and Tsonga); nearly 9.6 percent of people are white; 8.9 percent are “coloured” (mixed-race people) and 2.5 percent are Indian/Asian. This complexity encompasses 11 languages plus several dialects. This heterogeneity has evolved into a homogenous framework through Mandela’s reconciliation efforts.

4.3. Mandela’s reconciliation initiatives through judicial acts

Judicial acts are one of the most significant indicators of reconciliation initiatives; therefore law has a pivotal role to play in the reconstruction and empowerment of society. As John Hatch states that “justice equals reconciliation” and W. Zartman remarks that “there is no lasting peace without justice,”emphasising the significance of equal justice for all. However, maintaining justice in peace-building represents a sensitive part of the process, so a balance must be found between the necessity for tribunals to punish perpetrators and granting perpetrators amnesty to avoid disturbing a fragile peace. In the early days of the Mandela government, the primary issue was how to deal with the human rights abuses committed during apartheid. After long negotiations, the parties accepted an Interim Constitution (1993-1999), which allowed institutions to confront the legacy of human rights abuses and contained an amnesty provision for those who were responsible for offenses committed for political reasons. A centralized constitutional court model was chosen for the Interim Constitution to make a distinct break from the previous constitutional dispensation. The main principle was to protect basic human rights without discrimination; therefore it contained a chapter on fundamental rights to invalidate any law that might restrict basic human freedoms, irrespective of which party had political power in the country.

Other important judicial acts included the Land Restitution and the Affirmative Action Programme. The former intended to grant access to farming land for the black population, which has been prohibited from such land since 1913, and was quite successful. The latter aimed to introduce black people into areas of labour and the economy that had not been accessible to them in the past. The land restitution programme was prepared to tackle land issues and produced some encouraging results; for instance, by 2005 nearly 58, 000 of the 79, 000 claims that had been brought forth were solved amicably.Although there has been further improvement, one of the strong criticisms of Mandela’s government has been land restitution, the overall results of which have not satisfied black society. Several other programmes have achieved a huge measure of social engineering in the process of reconciliation. However, the most well-known action is the 1995 Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act No.34, which established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Most of the cases dealing with reconciliation in practice accept the TRC as a suitable model. Thus, truth commissions have usually emerged as part of transitions from authoritarian regimes to democratic political systems. These commissions are non-judicial bodies that generally prepare a report of their investigation with recommendations for future reform. However, some truth commissions have implemented additional activities, including naming perpetrators, granting amnesty, or providing reparations. Since the 1970s, nearly 40 truth commissions have been established to uncover the truth about human right abuses. However, the best known among these is South Africa’s. Although commissions do not have prosecutorial powers, the South African TRC had the power to grant amnesty.

By far, the most important and controversial of all Mandela’s initiatives was establishing the TRC. In November 1995, Mandela was selected as head of the TRC, with Archbishop Tutu as chair and Alex Boraine (South African Politician) as vice-Chair. The TRC’s overarching goal was to promote national reconciliation and unity in a spirit of understanding. The TRC objectives were to investigate the gross human rights violations committed between March 1, 1960 and May 10, 1994, which was the period of legalized apartheid. The specific violations under investigation were killing, torture, abduction, and severe ill-treatment. The TRC allocated the conflicts and divisions of the past to one of three sub-commissions: human Rights Violations (HRV), Amnesty, and Reparation and Rehabilitation (R&R).The TRC also had an investigative unit and witness protection programme.

The HRV Committee was authorized to take, investigate, and verify victim testimony; to establish the identity of individual and institutional perpetrators; and to designate accountability for gross human rights violations.The Committee was responsible for collecting statements from witnesses and victims recording the extent of these violations, and the Committee invited victims to speak in a public forum about their suffering. The Committee took the testimony of over 21,000 victims, with nearly 10% of these testimonies being given at public hearings on TV, in churches, and at town halls. The public hearings started on April 15, 1996 and lasted for two years.

The Amnesty Committee considered granting amnesty to apartheid perpetrators under strict conditions: 1) the crime had to have been committed between May 1, 1960 and May 10, 1994; 2) the crime had to be “associated with a political objective,” so the applicant had to have been an affiliate of one of the political parties during the conflict; and 3) “the perpetrator had to admit fault” (but a justification such as self-defence) and thus he/she had to disclose the full truth. If any person was deemed eligible for amnesty, the committee had to consider the person’s motive as well as the nature of the act. The TRC Act specifies that any person who acted for personal gain would not qualify for amnesty. If the crime was a gross violation of human rights, the Amnesty Committee had to conduct a public hearing before granting amnesty. The amnesty programme was a highly controversial issue and the ANC faced a massive dilemma in this regard.

The task of the R&R Committee was to provide recommendations on victim reparation. The Committee members were medical doctors and mental healthcare professionals was charged with the responsibility of evaluating the statements and applications provided by the HRV Committee and the Amnesty Committee. If the HRV Committee approved applicants as victims, then those people and their families could apply to the R&R Committee for reparation. The R&R Committee then made recommendations to the president of TRC about how to restore the victims’ human and civil dignity. The Committee recommended that each victim or family receive approximately $3,500 USD each year for six years.As balancing the inequality and degrees of suffering would be difficult to price, the committee recommended the same reparation for each individual. As a general point, the R&R Committee could not meet expectations of the victims. In the payment of reparations, long delays took place and the amount of reparations paid to 21.000 victims was quite lower than what it has been recommended. Additionally, government refused to announce the amount of remaining money that was reserved for reparations, therefore R&R is seen as the least successful, but also the least contested of the three committees.

The mission of the HRV Committee finished in June 1998. The proceedings of the Amnesty Committee continued until 2001 due to the overwhelming number of amnesty applications. The TRC’s Final Report was presented to then-President Thabo Mbeki in 2003. The HRV Committee documented more than 22,000 registered victims, of which 2,500 received the opportunity to testify. Over 8,000 South Africans (including members of the South African government and resistance groups) applied for amnesty, and the TRC pardoned several hundred of these applicants.Regarding aspects of reconciliation, both whites and blacks confessed to apartheid crimes of police brutality and collective punishment during the apartheid years. Though the ANC initially refused to seek amnesty for any of its own members, 22 ANC members who confessed to killing and maiming were tried and pardoned. Truth telling, seeking forgiveness, and confronting past suffering was essential in achieving reconciliation.

Although the TRC’s overall contribution to South Africa’s national reconciliation process is irrefutable, several criticisms have been raised against its structure, implications, and expected outcomes. To cover all criticisms is beyond the scope of this article; however, substantial ones are underlined. First, the TRC was accused by activists and scholars for re-traumatising victims and denying them true justice, especially by granting amnesty to perpetrators. Lerche maintains that the TRC favoured perpetrators over victims and that the perpetrators had more to gain by receiving amnesty than victims had through reparation. As some claim that when punishment is denied it leads to resentment and vigilantism, they say that the TRC failed to save victims’ respect and dignity when it encouraged them to forgive and reconcile with perpetrators. Pursuing reconciliation without punitive justice was a controversial and explosive issue which further underscored the inequality between perpetrators and victims. It has also been argued that pursuing reconciliation was fundamentally illiberal, and several questions about the achievements of the TRC and national reconciliation initiatives have not been resolved. All these criticisms have some sort of legitimacy; however, given its situational constraints of the time and atmosphere, the TRC still made great strides in reconciliation. The process may have resulted in less than perfect justice, but releasing the truth (from both the black and white perspective) and seeking forgiveness smoothed the process; the TRC in South Africa resulted in more reconciliation in less time and at a lower cost than war crimes tribunals have, such as those of the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

As a result, contrary to the expectations of the many who predicted conflict and chaos after apartheid, South Africa has come through the process with minimum losses thanks to the reconciliation efforts of Mandela. The question of whether these efforts really had an influence on interracial coexistence is outside the scope of this study, but Gibson’s survey provides a general answer. Gibson analysed the replies of 3727 respondents to nine survey statements about racial reconciling in 2004. Nearly half of the black respondents scored as “less reconciled.”In the same research, he found that more than half the white and coloured South Africans expressed some form of reconciliation, while only one third of black South Africans did so. From these results, although reconciliation efforts appear to have had more of a positive impact on non-black society than on black society, there are still positive effects.

Mandela’s success cannot be fully understood without knowing the potential power of white minorities. At the time of democratic transition, white minorities were still influential in all spheres of society, which could have made them capable of sustaining the apartheid regime for at least a few more decades. Mandela was well aware that there would be no solution and progress without the consent of the whites, and he through there may be two outcomes: white minorities would leave the country or, if they felt there was no future for them within South Africa, they would try to set up a separate state. While their economic, military, and human capabilities were quite sufficient to maintain the latter, Mandela’s reconciliation-oriented efforts gave whites a sense of belonging in the new South Africa. Such persuasion was no mean feat; preventing a massive exodus of white people and convincing black people of the merit of reconciliation instead of retribution was the key to success in the new democratic South Africa.

5. Conclusion

This article has scrutinized the national reconciliation of South Africa and the role of Nelson Mandela through his normative statements and symbolic and judicial acts. Instead of investigating the results of reconciliation-oriented efforts on society, the paper points out Mandela’s strategic function in orchestrating intergroup coexistence. Throughout this article, we claim that grassroots leaders play a strategic role in maintaining national reconciliation. As illustrated in the case of South Africa, no leader but Mandela, especially within his/her lifetime, could have eradicated the legacy of racial acts that left a society suffering from psychological and physical injuries for nearly a century. Considering Mandela’s situational constraints, his contributions toward national reconciliation are irrefutable; and it is precisely these that turned South African history in a positive direction. Abolishing long-lasting apartheid rules, enforcing the Truth and Reconciliation process, implementing restitution, and in particular affirmative action, land restitution, black economic empowerment, constitutional development, ending political violence, and transforming the educational system are some of Mandela’s initiatives that occurred within the first decade of the new nation.

This article has also underlined three essential facts for understanding the strategic importance of Mandela’s efforts: 1) South Africa’s historical background; 2) the society’s heterogeneous structure; and 3) the potential power of the white community. Being aware of the difficulty of reconciliation right after apartheid, Mandela’s endeavours stand as a great example of success despite of his social, economic, and political constraints, even if the degree of reconciliation thus far achieved is considerably less than complete. It is clear that the process of national reconciliation was well-established in the Mandela era. Before the 1999 general election, public satisfaction with Mandela’s performance stood at 80 percent; even 59 percent of white South Africans believed that Mandela was doing his job well. However, when Mandela stepped down from government in 1999, reconciliation began to lose its impetus and motivation. Subsequent leaders have not carried on his legacy; they have not implemented effective measures to continue to address South Africa’s problems. Today, although South Africa has one of the world’s most advanced democratic constitutions; the apartheid era’s racial classification has been replaced by economic classification. Currently, South African society faces an increasingly widening gap between rich and poor, a high level of corruption in the private and public spheres and a less-than- effective administration of justice.