Yasemin Akbaba

Gettysburg College

Jonathan Fox

Bar-Ilan University

This study examines shifts in governmental religion policy and societal discrimination against religious minorities in Muslim-majority states after the Arab Uprisings by using the Religion and State round 3 (RAS3) dataset for the years 2009-2014 and by focusing on 49 Muslim-majority countries and territories. We build on threads of literature on religious pluralism in transitional societies to explain the changes in governmental religion policy and societal discrimination against religious minorities after the Arab Uprisings. This literature predicts a rise in all forms of discrimination in Arab Uprising states as compared to other Muslim-majority states, and an even more significant rise in societal religious discrimination since societal behavior can change more quickly than government policy, especially at times of transition. The results partially conform to these predictions. There was no significant difference in the shifts in governmental religion policy between Arab Uprising and other Muslim-majority states, but societal religious discrimination increased substantially in Arab Uprising states as compared to non-Arab Uprising states. Understanding the nature of religion policies and religious discrimination provides further opportunities to unveil the dynamics of regional politics as well as conflict prevention in the region.

1.Introduction[1]

The Arab Uprising, by demanding social justice and freedom, inspired hopes of change in a region where democratic prospects have been in short supply.[2] While demonstrations led to a stable political transformation in Tunisia, uprisings escalated from acts of violence into civil war in Syria, Libya, and Yemen. With the notable exception of Tunisia, a short-lived era of optimism in each region gave way to a state of chaos, confusion, and eventually what has come to be termed the “Arab Winter”.[3] To a large extent, the goals of the Arab Uprisings were lost before they were realized. In the following months of protests, restrictions on freedom such as continuing or escalating discrimination against religious minorities surfaced.[4]

In the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings, tensions remain high in the region as religious tolerance deteriorates in societies with already deep sectarian divides. However, scholarship on religious liberty has yet to capture the changing landscape of governmental religion policies (such as religious discrimination) since the Arab Uprisings. Although various studies suggest the deteriorating treatment of religious minorities in Arab Uprising states, Fox in his analysis of the treatment of religious minorities from 1990 to 2008 demonstrates that “religious discrimination is present and increasing” in both Christian and Muslim majority states, “including Western democracies which are supposed to be among the most tolerant in the world.” [5] With the exception of the Pew report, none of the relevant work compares religious discrimination trends in the pre- and post-Arab Uprising Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region with a cross-sectional, quantitative methodology.[6] The Pew report covers only one Arab Uprising year (2011) and it does not provide detailed information on discrimination trends in different sub-categories, such as core Arab Uprising countries as compared to others. In addition, the Pew data does not differentiate between the religious freedom of religious minorities and the religious freedom of members of a country’s majority religion.[7]

This study asks the following questions: Has governmental and/or societal religious discrimination against religious minorities changed since the Arab Uprisings? Are governmental religious policy patterns different in Arab Uprising countries compared to non-Arab Uprising countries in the MENA or non-MENA Muslim-majority states? We build on the threads of literature on religious pluralism in transitional societies to provide a viable theoretical framework that explains the changes in religion policies and discriminations against religious minorities after the Arab Uprisings.

Transition periods present an opportunity for governments to update formal and informal policies of the state. One prominent example of this is governmental religious discrimination. Previous scholarship on regime transition suggests that restrictions targeting religious minorities tend to increase at times of political transition. This literature predicts that all forms of religious discrimination against religious minorities will increase (alongside other governmental religious policies) in transitional regimes such as the Arab Uprising states as compared to non-Arab Uprising states in the region, as well as in other Muslim-majority states outside of MENA. Societal behavior can change more quickly than governmental policy at times of transition since it takes longer to update the legal framework of a state than the attitudes of a society.[8] Therefore, we predict that societal religious discrimination will escalate more than governmental religious discrimination in Arab Uprising states.

We utilize round three of the Religion and State (RAS) dataset, which includes data on governmental religion policy and societal discrimination between 2009 and 2014. In this study we focus on 49 Muslim-majority countries and territories. The analysis shows that there is no evidence that government policy in Arab Uprising states changed significantly in a manner different from other Muslim-majority states. This applies to government-based discrimination against religious minorities, regulation of the majority religion and all religions in the country, and support for religion. The results indicate that societal discrimination increased substantially in Arab Uprising states as compared to other Muslim-majority states. Taking into consideration identity-based divides that shape regional politics, these results present implications for conflict prevention in the region.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: Section two reviews the existing literature on religious freedom in transitional regimes in the context of the Arab Uprisings. The research design section, presents the data and operationalization of the variables. We will then report our findings, and finally, present our conclusions.

2. Religious Pluralism in Transitional Societies

Regime transitions are known to be complex experiences that yield a diverse set of political outcomes. Scholarship on transitional regimes finds democratization attempts to produce intolerant governmental and social attitudes that welcome nationalist and religious outbidding tendencies.[9] Transitional regimes tend to restrict religious freedom as religion revives and religious regulations increase.[10] In addition, in a transitional regime, the desire for legitimacy leads to the creation of religion policies that aim to strengthen the government’s authority and power. Interestingly, a government’s yearning for legitimacy does not yield a single form of religious policy. As Fox suggests, states may “seek religious legitimacy” or simply “fear its use against the state.” [11] Egypt’s political adventures since the Arab uprisings present an example of this complexity. Right after the uprisings, the Muslim Brotherhood, as a significant political force, highlighted its legitimacy through religious policies that expanded the role of religion in politics. Since the toppling of Morsi and political marginalization of the Muslim Brotherhood, legitimacy of the government is centered on control of religion. Simply put, aspects of government religion policy may emerge as governmental religious discrimination, religious support or restrictions placed on all religions.

This paper situates post-Arab Uprising governmental religion policies under the transitional regime scholarship to understand how religious liberty has changed in a region where the “robustness of authoritarianism”[12] and “democratic deficit”[13] had been defining attributes for many years.

There are several bodies of literature that examine transitional regimes and democratization.[14] Part of this scholarship identifies the likely conditions and characteristics of transitional systems, such as the “politicization of ethnicity and the rise of nationalist movements,”[15] as well as the increasing tendencies toward violence and war.[16] Mansfield and Snyder[17] suggest “institutional capacity”, “severe ethnic divisions”, “democratic character of the surrounding international neighborhood”, and “availability of an effective power sharing system” to be important factors that shape the outcome of a transition.

Transitional regime scholarship also explores how the transition process impacts ethnic and religious minorities. Embracing ethnic and religious pluralism has proven to be a common challenge to most transitional societies. It is frequently observed that minorities get “the short end of the stick” at times of transition due to the collective mindset of the majority. This mindset tends to focus on preserving the national unity of the state, which is perceived to be weak, fragile and unstable, at the expense of pluralism. Anderson,[18] referring to survey data from “post-Soviet societies”, reveals peoples’ perception of democratic rights:

…for many people strong leadership and the restoration of ‘order’ were more important than democratic niceties, and that society and elites had yet to imbibe the values of tolerance and acceptance of diversity that tend to underpin mature democratic states.

Although it does not focus on transitional regimes, securitization scholarship suggests a similar dynamic. Securitization theory suggests a state representative can securitize an issue by invoking security.[19] Securitized issues are prioritized since they pose a threat to national security. The urgency of eliminating a threat opens the possibility of using unusual strategies.[20] In some cases, these strategies are not guided by democratic norms and principles even in democratic states. A religion or a religious group could be securitized. For instance, Cesari examines the securitization of Islam. [21] This theory is also used to explain restrictions on religious freedom. Fox and Akbaba use securitization theory to study religious discrimination against Muslims in comparison to other religious minorities in Western Democracies.[22]

Patriotic sentiments tend to strengthen exclusionary policies as competition among political actors facilitates the marginalizing political rhetoric that targets ethnic and/or religious minorities.[23] In addition, harsh responses to the demands of minority groups are normalized as ethnic and religious outbidding tendencies increase.[24]

Outbidding scholarship advances our understanding of societies in transition and what this means for pluralism. According to Snyder’s[25] work on nationalist outbidding, political elites utilize outbidding tendencies to improve their nationalistic qualifications[26]. Mansfield and Snyder[27] suggest transitions to democratic regimes with “weak domestic institutions” can be violent, and that tensions across ethnic groups can be high at these times.[28] Since countries with “weak domestic institutions” are not equipped to accommodate the increasing political demands of previously marginalized groups, these countries often end up with “belligerent ethnic nationalism or sectarianism” that then inspires either civil strife or outside intervention.[29]

Much like in the nationalist outbidding process, in religious outbidding, political elites use religious outbidding to better qualify for their position. Toft[30] outlines the dynamics and conditions of religious outbidding and explains why it is common in transitional regimes. In the process of religious outbidding, political elites try to outbid the opposition by reframing “secular domestic threats to their tenure … as religious threats.”[31] She suggests that religious outbidding frequently takes place in transitional regimes as it presents an opportunity for political actors to boost their credentials domestically and internationally.[32]

Posen[33] highlights a similar mechanism as he applies the security dilemma concept of international relations theory to ethnic conflict scholarship. Posen[34] suggests that “the collapse of imperial regimes can be profitably viewed as a problem of ‘emerging anarchy.’” As groups try to address security concerns due to the disintegration of a central government, they could create security concerns for others that then lead to a security dilemma. In other words, much like international actors, ethnic groups could challenge the security of other groups as they try to advance their own security. Posen’s application is expanded to understand the role of discrimination in the context of the ethnic security dilemma. [35]

Political transitions in Southern and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and South Africa (among others), ushered in a research agenda on democratic consolidation and religious pluralism in transitional regimes.[36] Although commitment to religious freedom and high democratic performance appear to be a challenge, transitional societies do not treat religious communities in a uniform manner. Numerous attributes of states, such as dominant religious affiliation, overlap of national and dominant religious identity, fears of instability, and competition among religious actors within a state, are discussed as explanatory factors for this variation. However, despite this variation, previous research suggests a common pattern running across transitional societies regarding the treatment of religious minorities. Anderson[37] examines the nature of religious freedom at times of change and how attitudes towards religious pluralism are shaped and guided by the need for national unity during unstable times by focusing on five transitional societies: Spain, Greece, Poland, Bulgaria, and the former USSR.[38] Although there is variation in religious freedom in these cases, the author discusses the presence of “broad types or families of arguments” across the five transitional regimes.[39] One of these arguments focuses on “a general need in transitional societies for order and stability in the face of uncertainty” which opens the way to “regulation of inappropriate or divisive religious activity.”[40] Anderson[41] successfully demonstrates the challenge of creating a democratic mentality in transitional societies and the implications of this process for religious minorities.

Anderson reports that in most of the cases he examined, religion’s significance in politics increased due to “its role in discourses about national identity and models of future developments.”[42] He claims that

the politics of religious liberty in transitional societies has a significance that transcends the narrowly religious. It suggests that religion will periodically erupt into the public domain, that the ‘privatization’ of religion is far from complete, and that historical legacies and contexts will continue to shape the ways in which politicians and political systems handle the public role of religion.[43]

Religious legitimacy scholarship echoes this argument. Religion is known to be a double-edged sword when used as a tool for political legitimacy. Faith and religious actors could boost or weaken the legitimacy of a government.[44] Therefore, in transitional regimes we might observe a broad spectrum of religious policies, including governmental religious discrimination, religious support, or restrictions placed on all religions. Among different forms of religious policies, discrimination emerges as a prominent one. Anderson suggests that “the countries where intolerance is more prominent are also countries where identity questions remain to the fore.”[45] Moreover, he observes “a correlation between the broader level of societal tolerance and the degree of restriction or freedom available to minority religious groups.”[46] Similarly, Sarkissian[47] finds tendencies of religious discrimination in transitional societies as she explores the “stalled progress in the realm of religious freedom” in post-communist states. More specifically, she suggests that “the benefits allotted to formally and informally established churches are often accompanied by legislation that attempts to curb minority religious rights. Moreover, minority religious groups often suffer from campaigns intended to instill fear in local populations, and are perceived as a threat to ‘traditional’ religions and national culture.”[48]

However, there is no study that situates the ebb and flow of post-Arab Uprising religion policies under the broader transitional regime literature. Prior to the uprisings, discrimination against religious minorities was considered to be “the rule rather than the exception” in the region.[49] For instance, the Pew Research Center reported that governmental restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion scores have been higher in the Middle East and North Africa than in any other region over the 2007-2011 time frame.[50] The same report also noted an increasing trend of social hostilities involving religion in the Middle East and North Africa for 2011.[51] Moreover, various studies suggested worsening treatment of religious minorities in Arab Uprising states.[52] Studies on the causes of discrimination identify various factors in order to explain variations in restrictions such as regime type, past discrimination of the state, and population dynamics.[53]

Findings on regime type suggest that democracies discriminate less than non-democracies.[54] Economic development is known to influence the dynamics of discrimination, but the direction of its impact is not clearly established.[55] It is also commonly argued that regimes with a history of discrimination are likely to repeat similar policies.[56] In addition, recent research on religious restrictions highlights the rise of religious discrimination over time. Fox[57] shows that there is a worldwide rise in different forms of governmental religion policy including support for majority religions and regulation of religion in general. Thus, any post-Arab Uprisings rise in religious discrimination or other forms of religion policy in Arab Uprising states may be part of a larger worldwide trend rather than due to the events of the Arab Uprisings.

These works provide useful guideposts for highlighting scope of change in the region for religious groups. However, scholarship on religious minorities is yet to capture the changing landscape of religious discrimination since the Arab Uprisings. More specifically, shifts in governmental and/or societal religious discrimination against religious minorities as well as other types of government religion policy need to be examined.

The transitional-society literature we outline above predicts an increase in both societal and governmental religious discrimination against religious minorities as well as an increase in other types of government religion policy in Arab Uprising states as compared to other Muslim-majority states both inside and outside of the MENA. Furthermore, we anticipate societal religious discrimination to escalate more than governmental religious discrimination in Arab Uprising states. In their study on societal discrimination, Grim and Finke[58] expand the conventional focus of religious discrimination literature, i.e. simply examining a state’s restriction of religious freedom, to include “social restrictions that inhibit the practice, profession, or selection of religion.” Their central argument is that societal restrictions are often a precursor to government-based restrictions on religious minorities. Implicit in this argument is that societal attitudes toward religious minorities change quickly based on current events and that these changes in societal attitudes, if they remain stable, eventually result in government policies which reflect them. However, policy change is slow and often lags behind societal change by a considerable margin. Finke and Martin suggest that this lag-time exists because changing government policy through social pressure requires some organization:

Working through social and political movements, as well as more formal political and religious institutions and leaders, the majority groups can reduce religious freedoms by advocating formal legislation or by applying informal pressures to local institutions. [59]

We suggest that the political environment that emerged during the instability and regime change caused by the Arab Uprisings created opportunities for changes to develop in societal attitudes toward religious minorities, as well as the emergence of latent negative attitudes toward religious minorities. This then resulted in an increase in societal religious discrimination against religious minorities in the Arab Uprising states. However, the organization necessary for this to translate into government policy, assuming such a transition occurs, is likely to take more time.

For instance, after drawing parallels between a long history of state-level intolerance and societal-level intolerance in the case of Egypt, Rieffer-Flanagan suggests that “the societal discrimination, harassment and violence that prevents freedom of religion and belief from being realized in Egypt arises from intolerant messages in civil society, in the media and in educational settings”.[60] The tendencies to perceive religious diversity as a threat to national unity increase with the marginalizing rhetoric that divides these societies along religious lines.

As outlined in the previous paragraphs, the fragile condition of transitioning states, combined with religious outbidding tendencies and the impact of political openings for actors that were previously oppressed, facilitate and justify the tendencies of social religious discrimination against religious minorities. Times of transition involve social tension and polarization. Moreover, new institutional infrastructures tend to be weak at times of transition.

In the same vein, we expect social hostilities to be more prominent than governmental discrimination. In other words, we expect social discrimination to be more visible than governmental discrimination since the political context can be more forgiving of social hostilities at times of transition and political upheaval. Therefore, various groups and actors might display discrimination through societal discrimination rather than with governmental discriminatory policies. In addition, long-lasting discriminatory policies at the state level make societal discrimination more acceptable at times of transition. Societal discrimination has a lower cost since often, during times of transition, the state fails to protect or ignores the security concerns of religious minorities.[61] What is more, societal behavior changes more quickly than government policy at times of transition since it takes longer to update the legal framework of a state. The “rules of the game” are defined more rapidly by social norms than by government in transitional societies, and shape social interactions more dominantly. Therefore, in the aftermath of the uprisings, we expect an increase in social religious discrimination against religious minorities in Arab Uprising countries.

3. Research Design

3.1. Which countries are Arab Uprising countries?

While the Arab Uprisings is an often-discussed term, there are different perceptions of which countries are considered to have experienced the Arab Uprisings. Moreover, there are variations in the nature of the Arab Uprising movements and their outcomes.[62] In addition, various terms such as unrest, uprising, protest, and demonstration are used to explain the diverse set of social mobilizations that have changed the political landscape of Middle East and North Africa. We draw from eight sources to determine which countries should be included in the study as Arab Uprising countries.[63] We designated countries identified by at least seven of these sources as core Arab Uprising states (Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen). Syria codings are available only through 2012 because after that year there was no effective government. Countries that are included in at least three of these sources are designated as other Arab Uprising states (Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, and Saudi Arabia). All other Muslim-majority MENA states and territories are considered separately as a basis for comparison, as are all Muslim-majority countries outside the MENA.

3.2. The religion and state (RAS) round 3 dataset

This study uses data from 49 Muslim-majority countries in the RAS3 dataset and covers the years 2009-2014. This time period uses 2009 and 2010 as baselines for the years previous to the Arab Uprisings. As the first Arab Uprising began in late December 2010, most of its influence should begin in 2011. 2014 is the most recent year available in the RAS3 dataset.

RAS3 was collected using the same methodologies as previous rounds of the RAS dataset. Each country was examined using multiple sources, including government reports, NGO reports, media reports (primarily from the Lexis-Nexis database), primary sources such as constitutions and laws, and academic sources. These reports were the basis for coding the variables.[64]

We use four variables from the RAS3 dataset, three which measure aspects of governmental religion policy, and one which measures societal discrimination against minority religions. In this section we briefly discuss the variables.[65]

The first three focus on policies by governments that include laws, formal and informal government policies, and actions taken by government representatives and officials. First we measure governmental religious discrimination. This is defined as restrictions placed by the government or its representatives on the religious institutions or practices of religious minorities that are not placed on the majority religion. [66] Fox argues that the distinction between restrictions placed on minorities and those placed on the majority religion “is critical because actions that can be quite similar have considerably different implications depending on the object of these policies”. [67] For example, if restrictions on places of worship are applied to all religions, this implies a regime that is generally anti-religious; if this restriction is applied only to minority religions it implies a regime that is not necessarily opposed to all religion, just to minority religions. This measure looks at 36 types of restrictions placed on religious minorities, each coded individually, including 12 types of restrictions on religious practices, eight types of restrictions on religious institutions and clergy, seven types of restrictions on conversion and proselytizing, and nine other types of restrictions. Each individual type is coded on a scale of zero to three based on severity, resulting in a measure that ranges from zero to 108.

We then measure restrictions that are placed on all religions, including the majority religion. This measure includes 29 such restrictions, each coded individually, including five types of restrictions on religion’s role in politics, ten types of restriction on religious institutions, seven types of restriction on religious practices, and eight other types of restrictions. Each type is coded on a scale of zero to three based on severity, resulting in a measure that ranges from zero to 87.

Third, we measure religious support—the extent to which a government actively supports religion. This measure includes 52 types of support, each individually coded on a scale of zero to one, with ‘one’ meaning the type of support is present. The types of support in the measure include 21 types of religious law or precepts that are enforced by the government, five types of institution or government activity intended to enforce religion (e.g. religious courts), 11 ways the government can fund religion, six ways in which religious and government institutions can become entangled, and nine additional types of support. This measure ranges from zero to 52.

The fourth variable measures acts of discrimination, harassment, prejudice, or violence against members of minority religions by members of society who are not representatives of the government. This measure is intended to measure societal attitudes toward religious minorities. While many, such as Grim and Finke,[68] focus on attitudes, we posit that attitudes are difficult to measure in a comparable manner across countries and societies, but measuring concrete actions is far more feasible. This measure includes 27 types of actions, each coded individually on a scale of zero to three and based on severity, and including multiple types of public speech acts, vandalism, harassment, and violence (both against people and property). The resulting variable ranges from zero to 81.

We examine each of these four variables on a yearly basis, dividing all countries into four categories (described in more detail above): core Arab Uprising states, other Arab Uprising states, other MENA Muslim-majority states, and non-MENA-Muslim majority states.

4.Analysis

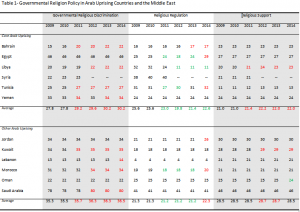

Tables one and two show governmental religion policy between 2009 and 2014 in 49 Muslim-majority countries. Governmental religious discrimination is rising overall in all four categories of the states examined. Among the core Arab Uprising states it increased in Bahrain, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen, and remained stable in Egypt and Syria. In Bahrain this was largely due to increased limitations of public expressions of religion by Shi’a Muslims and the destruction of Shi’a Mosques in 2011 during the Arab Uprising protests. In Libya and Tunisia it was due to the government’s inability or unwillingness to protect religious minorities from societal violence. In Yemen it was due to increased restrictions on the operating hours of Shi’a mosques.

Table 1- Governmental Religion Policy in Arab Uprising Countries and the Middle East

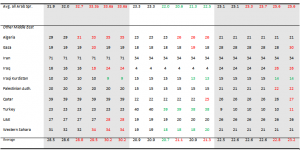

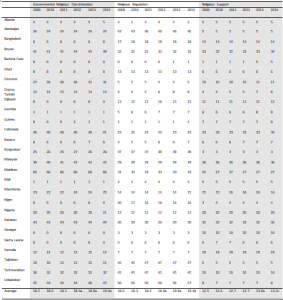

Table 2- Governmental Religion Policy in Muslim-Majority Countries outside the Middle East

Similarly, in four of the other six states experiencing Arab Uprising, religious discrimination increased. In 2011, Kuwait began arresting non-Muslims for eating and smoking during Ramadan. In Lebanon in 2015, the mayor of Tripoli began requiring that non-Muslim restaurants and cafés close during the fasting hours of Ramadan. In 2012, Morocco’s local authorities began closing unofficial house-churches where foreigners met to pray. In the same year, two Ahmadi brothers in Saudi Arabia were arrested and sent to a prison after refusing to recant their beliefs. This is the first recorded incidence of a governmental attempt at forced conversion in Saudi Arabia. In Jordan and Oman, levels of religious discrimination remained stable.

However, as noted above, these increases were not unique to Arab Uprising Muslim-majority states. Average levels of governmental discrimination increased in other MENA states as well as in Muslim-majority states outside the MENA. Of these 49 states it decreased only in Iraqi Kurdistan, and only slightly at that; Iraqi Kurdistan, while having an independent government, is not an officially recognized country. The results were statistically significant for all Arab Uprising states combined, and for all non-MENA Muslim–majority states combined.

Religious support also does not distinguish the Arab Uprising states. Overall, religious support increased slightly in core Arab Uprising states but this was mostly due to Libya, where Islamic extremists set up religious courts and began applying Sharia criminal law and enforcing religion-specific laws such as dress codes for women. Increased support for religion was also evident in several MENA non-Arab Uprising states as well as in several Muslim-majority countries outside the MENA.

Superficially it appears that the regulation majority religions decreased in core Arab Uprising states as opposed to remaining stable or increasing in all three other categories of state. This is primarily due to a severe decrease in the regulation of Islam after the fall of Kaddafi’s regime in Libya. Also, by 2014, regulation of majority religions had increased overall in more states than it had decreased; the measurement of government regulation of majority religions is at best inconclusive.

Thus, overall, there is no evidence in this descriptive analysis that government policy in Arab Uprising states changed significantly in a manner differently from any other Muslim-majority states.

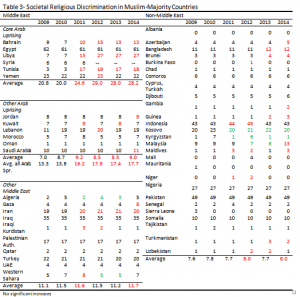

The results for the occurrence of societal religious discrimination presented in table three, however, are different. Overall, core Arab Uprising countries have experienced an increase in societal discrimination, despite a lack of statistical significance in the average score. Societal discrimination increased in three of the core Arab Uprising states, with a dramatic increase in Libya. This includes an increase in non-violent activities, such as desecrations of Christian and Jewish cemeteries, anti-Christian and Jewish demonstrations, and the occurrence of property damage (such as an arson attack on the Coptic Church in Benghazi). It also includes violent actions by civilian gangs and Islamic militia. Many of these attacks have been lethal, including the shooting of seven Coptic Christians in 2013, and beheadings in areas controlled by ISIS. In Tunisia the increase was dramatic, but less violent. It consisted of anti-Shi’a, anti-Sufi, anti-Christian, and anti-Semitic sermons by clergy, vandalism of Jewish and Christian religious sites, and the harassment of some members of these groups. Between 2011 and 2013 there was also a series of arson attacks against Sufi and Jewish religious sites. In Bahrain, the increase was modest and consisted of an increase of vandalism on Jewish and Shi’a property.

While these results are not statistically significant, they also do not include Syria because the RAS3 dataset does not code countries with no effective government. Had Syria been included, the violent actions taken against Christians in the country would likely have resulted in a large increase in the score for societal discriminations. In addition, the societal discrimination scores for Egypt are the highest in the world for each year between 1999 and 2014, making an increase less likely. Thus, it is arguable that the results for Syria and Egypt are skewing the average into a false negative.

The levels in the rest of the Muslim world remain relatively stable though societal discriminations increased as well as decreased by small amounts in several countries. The only non-Arab Uprising countries in which the score for societal discrimination increased by more than one point were Malaysia and the Maldives.

Table 3- Societal Religious Discrimination in Muslim-Majority Countries

5. Conclusion

The Arab Uprising was extraordinary series of events that destabilized regimes across the MENA. Outcomes of the uprisings are still unfolding and the transition process taking place in Arab Uprising states is far from complete. Based on the literature on religious pluralism in transitional societies, such a transitional period should lead to increases of societal and governmental religious discrimination as well as in other types of governmental religion policy. However, our findings show that governmental discrimination, as well as governmental support for and regulation of religion, did not change significantly in comparison to other Muslim-majority states, either inside or outside of the MENA. However, societal discriminations did increase substantially in the Arab Uprising states in comparison to other Muslim-majority states.

One of the potential explanations for the findings on governmental religious discrimination is related to the fact that religious discrimination is on the rise globally.[69] Another potential explanation involves the political traditions of Arab Uprising countries in comparison to those in post-Communist Europe, the latter having shaped transitional regime scholarship. As Romdhani[70] puts it,

Picking their way through the wreckage of Communism, the leaders of the 1989 European revolutions were able to tap into their own deep-rooted democratic traditions. The post-Arab Spring political classes had no such foundation, and were faced instead with a dreary and forbidding legacy of autocratic rule.

A quick look at tables one and two reveals high governmental religious discrimination trends in Muslim-majority states. Our results show that governmental discrimination increased in Arab Uprising states, but not in a manner different from other Muslim-majority states. However, the average scores of all the MENA states were already high before the Arab Uprising and although slightly lower, it was still high in Muslim majority states outside of the MENA. Similarly, Fox suggests that although there are notable exceptions, “[t]he Muslim world differs from the Christian world in that religious discrimination is considerably more common and severe, on average”. [71] In other words, in the short term, the societal dynamics of Muslim-majority states could more accurately measure the impact of the Arab Uprisings than government religion policies.

Alternatively, increasing religious discrimination in other Muslim-majority states may be due to the reactionary policies of non-Arab Uprising States that are concerned with a diffusion of the Arab Uprisings movement into their countries. It may also be related to the refugee crisis caused by a high number of citizens fleeing their homes in Syria. For instance, Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon receive many Syrian refugees. [72] In other words, although labeled as non-Arab Uprising Muslim-majority states, other states in the region may be indirectly impacted by the uprisings.

Although consistent with previous scholarship on transitional regimes, our findings on societal discrimination may be the canary in the coal mine. Anderson[73] suggests that

the cultural context in the countries undergoing transition may be important to determining outcomes in the religious sphere. Most studies of societies undergoing transition in a liberal or democratic direction suggest that in the long term the evolution of a democratic mind-set or democratic political culture is important. In the first instance this may simply require that elites agree to play by the new ‘rules of the game’ and that they accept the legitimacy of the emerging system, but in the longer term it is argued that stability requires some form of mass acceptance of the political system and, if the democracy is to be truly ‘liberal’, the emergence of mass values accepting of difference and tolerant of alternative viewpoints.

Similarly, Grim and Finke find that societal discrimination is often a precursor to governmental discrimination.[74] Therefore, further research is not only helpful in understanding regional politics, but in preventing conflict in the region as well.

This study adds to the literature on transitional regime and religious pluralism by incorporating the governmental religion policy trends in the Arab Uprising states. This is particularly true of our findings on societal discrimination in the Arab Uprising states. Our findings on governmental religious policies also advance our understanding of global religious policy. Although the long-term consequences of the uprisings are still unfolding, this study shows that the Arab Uprisings did not usher in an era of religious pluralism and social acceptance of religious minorities.

Akbaba, Yasemin, Patrick James, and Zeynep Taydas. “The Chicken or the Egg? External Support and Rebellion in Ethnopolitics.” In Intra-State Conflict, Government and Security: Dilemmas of Deterrence and Assurance, edited by Stephen M. Saideman and Marie-Joelle Zahar, 161-81. London; New York: Routledge, 2008.

Arar, Rawan, Lisel Hintz, and Kelsey P. Norman. “The real refugee crisis is in the Middle East, not Europe.” Washington Post, May 14, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/14/the-real-refugee-crisis-is-in-the-middle-east-not-europe/?utm_term=.7eb198775d41.

Anderson, John. Religious Liberty in Transitional Societies: The Politics of Religion. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

——— . “Social, Political, and Institutional Constraints on Religious Pluralism in Central Asia.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 17, no. 2 (2002): 181-96.

——— . “The Treatment of Religious Minorities in South-Eastern Europe: Greece and Bulgaria Compared.” Religion, State & Society 30, no. 1 (2002): 9-31.

Bellin, Eva. “Reconsidering the Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Lessons from the Arab Spring.” Comparative Politics 44, no. 2 (2012): 127-49.

——— . “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Politics 36, no. 2 (2004): 139-57.

Boogaerts, Andreas. “Beyond Norms: A Configurational Analysis of the EU’s Arab Spring Sanctions.” Foreign Policy Analysis (2016): 1-12. doi: 10.1093/fpa/orw052.

Brownlee, Jason. Authoritarianism in the Age of Democratization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Cesari, Jocelyne. “The Securitization of Islam in Europe.” CEPS Challenge, Research Paper No. 15, April 2009.

Chandra, Kanchan. “Ethnic Parties and Democratic Stability.” Perspectives on Politics 3, no. 2 (2005): 235-52.

Chaney, Eric, George A. Akerlof, and Lisa Blaydes. “Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present.” Brooking Papers on Economic Activity 42, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 363-414.

Črnič, Aleš. “Religious Freedom and Control in Independent Slovenia.” Sociology of Religion 64, no. 3 (2003): 349-66.

du Plessis, Lourens M. “The Protection of Religious Rights in South Africa’s Transitional Constitution.” Koers 59, no. 2 (1994): 151-68.

el-Issawi, Fatima. “The Arab Spring and the Challenge of Minority Rights: Will the Arab Revolutions Overcome the Legacy of the Past?” European View 10 (2011): 249-58.

Findley, Michael G., and Joseph K. Young. “More Combatant Groups, More Terror?: Empirical Tests of an Outbidding Logic.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24, no. 5 (2012): 706-21.

Finke, Roger, and Robert R. Martin. “Ensuring Liberties: Understanding State Restrictions on Religious Freedoms.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53, no. 4 (2014): 687-705.

Fox, Jonathan. “Are Middle East Conflicts More Religious?” Middle East Quarterly 8, no. 4 (2001): 31-40.

——— . An Introduction to Religion and Politics: Theory and Practice. Oxon: Routledge, 2013.

——— . “Is Ethnoreligious Conflict a Contagious Disease?” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 27, no. 2 (2004): 89-106.

——— . Political Secularism, Religion, and the State: A Time Series Analysis of Worldwide Data. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

——— . The Unfree Exercise of Religion: A World Survey of Religious Discrimination against Religious Minorities. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

———, and Yasemin Akbaba. “Securitization of Islam and Religious Discrimination: Religious Minorities in Western Democracies, 1990 to 2008.” Comparative European Politics 13 (2015): 175-97.

Frye, Timothy. “Ethnicity, Sovereignty and Transitions from Non-Democratic Rule.” Journal of International Affairs 45, no. 2 (1992): 599-623.

Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Gurr, Ted R. Peoples versus States: Minorities at Risk in the New Century. Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2000.

Hussain, Muzammil M., and Philip N. Howard. “What Best Explains Successful Protest Cascades? ICTs and the Fuzzy Causes of the Arab Spring.” International Studies Review 15 (2013): 48-66.

Huysmans, Jef. “Security: What do you mean? From Concept to Thick Signifier.” European Journal of International Relations 4, no. 2 (1998): 226-55.

Kamrava, Mehran, ed. Beyond the Arab Spring: The Evolving Ruling Bargain in the Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Lausten, Carsten Bagge, and Ole Wæver. “In Defense of Religion: Sacred Referent Objects for Securitization.” In Religion in International Relations: The Return from Exile, edited by Fabio Petito and Pavlos Hatzopoulos, 147-80. Palgrave: Macmillan, 2003.

Linz, Juan, and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Jack Snyder. “Democratization and the Arab Spring.” International Interactions 38, no. 5 (2012): 722-33.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Jack Snyder. “Prone to Violence: The Paradox of the Democratic Peace.” 82 The National Interest (2005/06): 39-45.

Neugart, Felix. “Uncertain Prospects of Transformation: The Middle East and North Africa.” Strategic Insights 6, no. 12 (2005). Accessed December 21, 2016. http://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/11342/Uncertain%20Prospects%20of%20TransformationThe%20Middle%20East%20and%20North%20Africa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Nossett, James Michael. “Free Exercise after the Arab Spring: Protecting Egypt’s Religious Minorities under the Country’s New Constitution.” Indiana Law Journal 89, no. 4, Article 8 (2014).

O’Donnell, Guillermo A., Phillippe C. Schmitter, Laurence Whitehead. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Prospects for Democracy. Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Posen, Barry R. “The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict.” Survival 35, no. 1 (1993): 27-47.

Rieffer-Flanagan, B. “Statism, Tolerance and Religious Freedom in Egypt.” Muslim World Journal of Human Rights 13, no. 1 (2016): 1-24. Accessed January 4, 2017. doi:10.1515/mwjhr-2015-0013.

Romdhani, Oussama.“The Next Revolution: A Call for Reconciliation in the Arab World.” World Affairs 176, no. 4 (2013): 89-96.

Sarkissian, Ani. “Religious Reestablishment in Post-Communist Polities.” Journal of Church and State 51, no. 3 (2009): 472-501.

Seiwert, Hubert. “Freedom and Control in the Unified Germany: Governmental Approaches to Alternative Religions since 1989.” Sociology of Religion 64, no. 3 (2003): 367-75.

Snyder, Jack. From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict. New York: W.W Norton, 2000.

Toft, Monica D. “The Politics of Religious Outbidding.” The Review of Faith and International Affairs 11, no. 3 (2013): 10-19.

Wæver, Ole. “Aberystwyth, Paris, Copenhagen: New 'Schools' in Security Theory and their Origins between Core and Periphery.” Paper Presented at annual meeting for ISA Conference, Montreal, March 2004.

———. “Securitization and Desecuritization.” In On Security, edited by Ronnie Lipschutz, 46-87. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.