Senem Aydın-Düzgit

Sabancı University

Bahar Rumelili

Koç University

Discourse analysis is a much-favoured textual analysis method among constructivist and critically minded International Relations scholars interested in the impact of identity, meaning, and discourse on world politics. The aim of this article is to guide students of Turkish IR in their choice and use of this method. Written by two Turkish IR scholars who have employed discourse analysis in their past and present research, this article also includes a personal reflection on its strengths and shortcomings. The first section of the article presents an overview of the conceptual and epistemological underpinnings of discourse analysis, while charting the evolution of discourse analysis in IR since the late 1980s in three phases. The second section offers insight into the personal history of the researchers in employing discourse analysis in their previous and ongoing research, while the third section provides a how-to manual by performing discourse analysis of an actual text. The concluding section focuses on the challenges faced in the conduct of discourse analysis and the potential ways to overcome them, also drawing from the researchers’ own experiences in the field.

1.Introduction*

Since the 1980s, discourse analysis has become a much-favoured method of empirical analysis, especially among constructivist and critical International Relations scholars. It is necessary to clarify at the outset that there is not a single method of discourse analysis. A wide range of scholars employ discourse-analytical tools in various ways—some more loosely and illustratively, others more systematically—and while doing so, operate from different theoretical vantage points. An even a wider set of scholars claim to be using discourse analysis while conducting in fact other forms of textual analysis. The purpose of the article at hand is not to impose a particular way of doing discourse analysis. Yet at the same time, we consider it important to situate discourse analysis as a distinct form of textual analysis, and clarify its key aspects so that not any reading of documents, speeches, and texts qualifies as discourse analysis.

In the first section of the article, we chart the evolution of discourse analysis in IR in three phases, and while doing so, introduce its theoretical underpinnings as well as the diverse ways of doing discourse analysis. In the first phase, discourse analysis was introduced to the discipline through the works of poststructuralist scholars, starting in the late 1980s. In these works, the use of discourse analysis was closely linked to poststructuralist theory, its assumptions regarding absence of agency, historicity and contingency of discourse, and post-positivist epistemology. In the second phase, discourse analysis was carried from the margins to the mainstream of the IR discipline through the works of constructivist scholars, who sought to employ discourse analysis in a more systematic manner in order to engage in competitive hypothesis testing with their rationalist counterparts. More specific discourse analytical methodologies developed drawing on linguistic analysis, such as predicate analysis, metaphor analysis, and critical discourse analysis. Scholars took greater care to clarify and justify text selection and developed analytical templates to guide their research. Greater emphasis was placed on demonstrating the effects of discourse, which led scholars to employ discourse analysis as part of an interpretive epistemology, often in combination with other interpretive methodologies, and relax the strict poststructuralist assumptions regarding lack of agency and intentionality. In the third and current phase, discourse analysis is experiencing both consolidation and greater engagement with other methodologies. It is now employed by a broader range of scholars, in some cases in tandem with quantitative approaches to textual analysis, as part of a wider mixed-methodological toolkit.

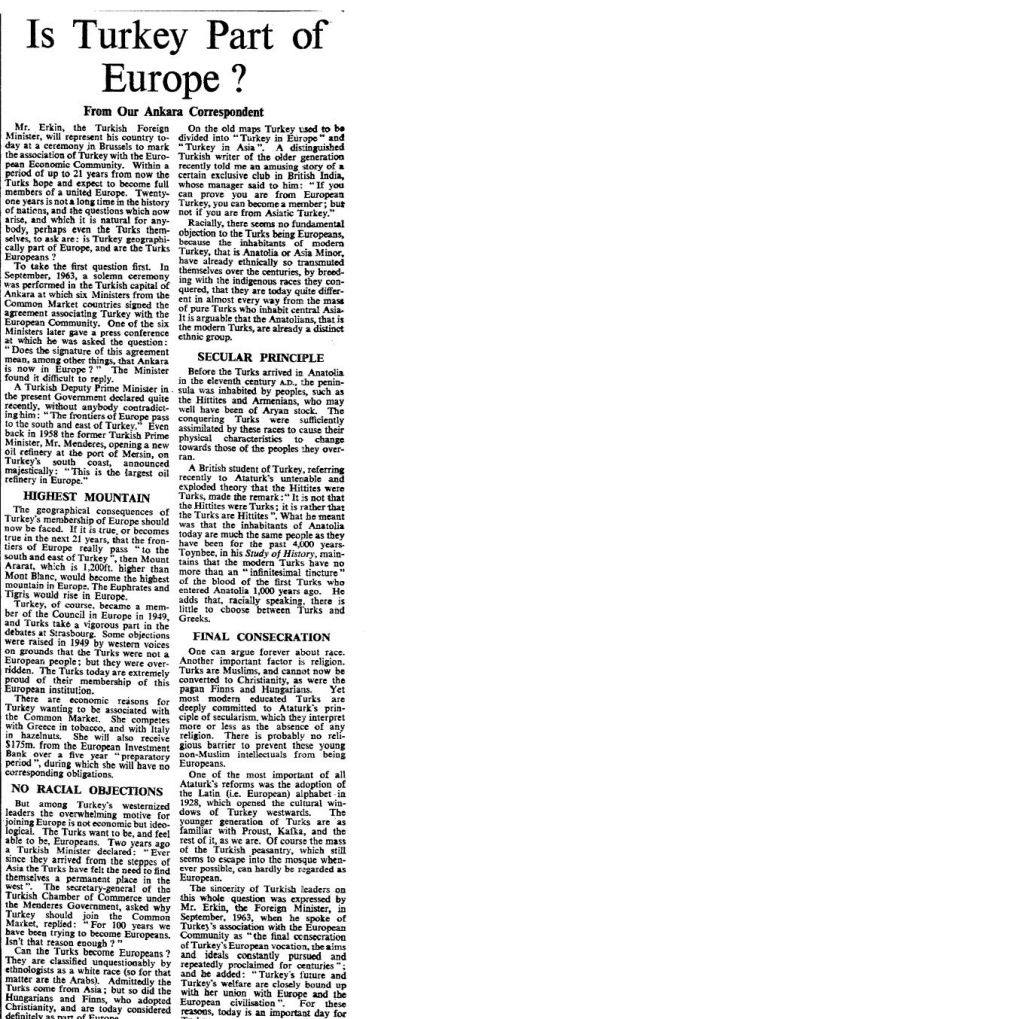

In the second section of the article, we discuss our personal experiences with employing discourse analysis in our own research, followed in the third section by a how-to manual performing discourse analysis of an article entitled ‘Is Turkey Part of Europe?’ published in the Times in 1963. The analysis follows the methodological template of critical discourse analysis, by identifying the nomination, predication, and argumentation strategies employed in the text. In conclusion, we briefly reflect on the strengths and shortcomings of this methodology, also drawing from our own experiences in the field.

2. Discourse Analysis in IR: Evolution and Key Premises

Neither discourse nor discourse analysis has a standard definition. For example, Reisigl[1] has argued that Michel Foucault used the concept of discourse in twenty-three different meanings during his famous College de France speech on discourse. Broadly speaking, discourse refers to taken-for-granted structures of shared meaning. In the Foucauldian approach, discourse determines what can and cannot be said, constitutes subjects, ascribes identities, and defines the boundaries of rational/irrational, legitimate/illegitimate action. For example, the discourse on Europe determines what can and cannot be said about Europe (e.g., a continent, an organization, an order, but not a company), who is European and who is not, and who can speak on Europe. In order to identify structures of shared meaning, discourse analysis analyses discursive practices[2]—for example, the discourse on Europe is analysed through what is said on Europe.

There are important theoretical differences between scholars employing discourse analysis, in terms of whether and how much individual discursive practices can shape and alter discourse. Whereas in the Foucauldian tradition, actors ‘articulate’ elements of a discourse within the subject positions constituted by discourse, IR scholars drawing on Wittgenstein’s language games and Austin’s speech act theories assume a greater degree of discursive agency, and consider discourse a product of individual discursive practices in the context of social rules and norms.[3] There are also important theoretical differences among discourse analysts on the degree to which discourses are susceptible to change and contestation. Derridaean-inspired discourse analysis emphasizes the contingency and inconsistency within discourse and the inability to fix meanings once and for all.[4] Habermasian-inspired discourse analysis, on the other hand, focuses on the consensual and consensus-generating aspects of discourse, and analyses discourse as a system of socially agreed justifications.[5]

The adoption of discourse analysis by IR scholars coincided with wide-ranging meta-theoretical debates in the discipline on ontology and epistemology at the end of the 1980s. During what is widely known as the Third Debate, a diverse group of scholars inspired by poststructuralist approaches challenged the widespread positivist assumptions in the discipline about objectivity, fact/value distinction, and the independent existence of truth.[6] Viewing the social world as constituted through language and discourse, poststructuralist IR theorists set out to analyse the traditional concepts of IR—such as anarchy, sovereignty, and foreign policy—as discourses of global politics; that is, as taken-for-granted structures of meaning that do not describe an independently existing state of global politics, but actually serve to constitute it as such.[7] In poststructuralist theory, discourse is closely interwoven with power.[8] Through their constitutive effects on reality, discourses exert power through rendering certain understandings as hegemonic and marginalizing others. For example, when anarchy is analyzed as a discourse of global politics, the pertinent question is no longer the validity of the anarchy assumption, i.e. whether or not the international system is indeed anarchical, but what the anarchy assumption does in terms of, for example, hiding various asymmetries in global politics. Thus, discourse analysis, for this earlier group of critical IR scholars, was not a methodological choice; it was embedded in their very conception of the IR discipline as a set of discourses and in their wholesale challenge to it. Hence, discourse analysis was employed to serve critical purposes, to de-naturalize dominant understandings by showing their historicity, to reveal relations of domination and power that are masked by the discipline, and to delegitimize claims to absolute truth.

One very well-known contribution to poststructuralist IR theory is David Campbell’s book Writing Security, which highlights the inextricable discursive link between foreign policy and the constitution of state as an actor with an identity. Against the conventional definition of foreign policy as the external behaviour of a pre-existing state with a pre-given identity, Campbell contends that state identity is constituted through foreign policy, which comprises both conventional foreign policy in the form of external behaviour as well as representations of Self and Other in state documents. Briefly put, according to Campbell, discourses on foreign policy constitute the state and its identity through constructing Others and representing these Others as antithetically different and threatening to Self. In order to show the prevalence and continuity of these representational practices, Campbell subjects a select number of key texts from different domains of US foreign policy across time to in-depth critical reading, such as the NSC-68, immigration forms and documents, etc.

In these critical endeavours, some poststructuralist IR theorists adopted the genealogical method of analysing the evolution of discourses in broader historical perspective. For example, Iver Neumann historically traced the representations of Russia in Europe, and pointed out the continued dominance of the representations of Russia as a threat.[9] Richard Ashley and Rob Walker showed how discourses on anarchy, geopolitical discourses, and inside/outside distinctions came to be constitutive features of the ways in which we conceive of International Relations.[10] Contemporary discourses acquire and maintain their hegemonic status through establishing artificial continuities with the past. Historicizing contemporary hegemonic discourses serves to reveal the specific socio-political contexts in which these discourses emerged and exposes their contingent evolution through challenges from and suppression of various alternatives. Thereby, the genealogical method serves to deconstruct the historical continuities that contemporary discourses rely on to maintain their hegemonic status.

Another important methodological tool employed by poststructural theorists is the juxtapositional method, which relies on the juxtaposition of a particular discursive construction with alternative narratives or with events and phenomena which cannot be accounted for by dominant narratives.[11] The juxtapositional method also serves to denaturalize dominant discourses and discredit their claims to absolute truth. For example, in his critical analysis of the American foreign policy discourse on the war on drugs, David Campbell juxtaposed the claims of the dominant discourse to statistical data in order to show that the same facts could equally well be used to advance competing claims.[12]

In general, this first wave of postructuralist discourse analysts focused on identifying hegemonic discourses and demonstrating the historical continuities, rather than on potential for change and contestation. As noted earlier, in poststructuralist theory, discourse has a complicated relationship to agentic representational practices. On the one hand, by determining what can and cannot be said, ‘discourse transcends the generative and critical capacities of any individual speaker or speech act’.[13] Discourses construct subject positions, and direct actors into speech acts and practices allowed by those subject positions. For example, the state is produced through discourses of insecurity, while nationalist discourses construct imagined communities linked by ethnicity, language and culture. No representational practice can be outside of discourse and hence totally contest a discourse without at the same time reproducing it. Quite often, oppositions and struggles against hegemonic practices end up reproducing the categories and hierarchies that are implicit in the dominant discourses that justify these practices in the first place. On the other hand, discourses are not fixed, and are continuously and gradually transformed through agentic representational practices, as each articulation adds new linkages to fluid discursive structures while subtracting others.[14]

The rationalist mainstream of the IR discipline generally dismissed discourse analysis in this earlier form as lacking methodological rigor.[15] In particular, it was claimed that the analyses offered by poststructuralists relied on subjective interpretations of a limited range of texts, and hence are neither replicable nor generalizable. Poststructuralist discourse analysts were equally dismissive of these criticisms, claiming that discourse analysis does not aim at producing new truth claims, because doing so would merely replace one regime of truth with another, and thus be contrary to postmodern sensibilities.

Starting with the 1990s, discourse analysis slowly transitioned from the margins to the mainstream of the IR discipline via constructivist scholars. Unlike the pioneers of the third debate, constructivist scholars were more interested in mounting an ontological rather than an epistemological challenge to the discipline,[16] and thus focused on demonstrating the socially constructed nature of IR phenomena. Positioning themselves as via media between rationalist mainstream and its poststructuralist challengers,[17] constructivists’ main interest lay with demonstrating that ideational factors such as ideas, norms, identity, culture, and other intersubjectively shared meanings matter in shaping outcomes in international relations. In order to identify these sets of shared meanings and to demonstrate their impact, constructivist scholars relied on a variety of methodologies, often combining discourse analysis of specific illustrative texts with interviews, process tracing, and counterfactual analysis.[18]

Apart from a group of critical constructivist scholars discussed below, it is fair to say that constructivist scholars employed discourse analysis as an interpretive rather than a critical methodology. In other words, discourse was analysed in order more to identify structures of shared meaning in a specific social context and less to reveal their historicity and complicity in domination. In crude terms, whereas Ashley was interested in what anarchy does, Wendt focused on identifying what states make of anarchy.[19] In addition, constructivist scholars aimed to address the criticism that poststructuralist discourse analysts of the earlier phase had faced from the rationalist mainstream, by clarifying and justifying their text selection, and outlining the steps of empirical analysis. They also devoted greater attention to outlining the methodology of discourse analysis in IR, and consciously adopted analytical methods from linguistics, such as predicate analysis, metaphor analysis, and critical discourse analysis.

Good examples representing more systematic discourse analysis of this form include Ted Hopf’s[20] study of Russian identity and foreign policy, which, in comparison to Campbell’s analysis of US foreign policy, relied on the analysis of a wider range of Russian texts, including official documents, speeches, newspaper articles, and popular culture. In addition, Hopf studied dominant and competing discourses in order to show how different identity narratives compete over the construction of Russian foreign policy. Scholars also developed elaborate analytical frameworks to typologize different representational practices. Both Rumelili and Hansen built on Campbell’s conception of IR as Self/Other relations, but argued that these relations take different forms, and developed typologies for representations of Self and Other in discourse.[21]

Simultaneously, in Europe, securitization theory, which concerned itself specifically with the question of how certain issues get to be represented as security issues, developed.[22] While also interested in linguistic construction of reality and the political effects of linguistic representations, securitization theory, like Wittgenstein’s speech act theory it drew upon, focused more on the purposive act of representing an issue as a security issue rather than on the structuring effects of security discourses. Hence, in comparison to poststructuralist theory which inspired the first wave of discourse analysis in IR, securitization theory operated from more relaxed assumptions regarding agency and strategic action in and through discourse. This more relaxed approach is also visible in Iver Neumann’s Uses of the Other, where he discusses how East European states in the 1990s employed identity strategies to position themselves in Central Europe while relegating their Eastern neighbours to the East, to strengthen their bid for membership in the EU.[23]

As discourse analysis transitioned from the margins to the mainstream of the IR discipline, it incorporated more detailed and systematic guidelines on textual analysis, mainly from linguistics. In particular, three specific and interrelated methodologies of discourse analysis developed in this period: predicate analysis, metaphor analysis, and critical discourse analysis.

In one of the earliest methods articles on discourse analysis, Jennifer Milliken had outlined various steps of a type of discourse analysis, referred to as ‘predicate analysis’, where discourses are treated as systems of signification, meaning that the relational differences and hierarchies that are established through discourse are displayed through an analysis of the linguistic practices in texts.[24] Predicate analysis with its empirical focus on the ‘language practices of predication: the verbs, adverbs and adjectives that attach to nouns’ quickly became one of the commonly used discourse analysis methods in the drive towards a more empirically rigorous discourse analysis in this second period.[25]

Doty also utilized this method of discourse analysis to demonstrate the continuity in representations of the South in colonial and contemporary discourses on modernization and development, and while doing so, outlined different effects of discourse, such as negation and denial.[26] By taking the cases of the US discourse on the Philippines and Britain’s discourse on Kenya, she demonstrated the ways in which binary dichotomies between the North/South such as modern/traditional, developed/less developed, and first world/third world have been naturalized through the use of predicates in discourse.

In addition to these classic works, predicate analysis has also been employed in more recent studies focusing on contemporary developments in international relations. Rumelili has subjected Turkish and Greek official and media discourse to predicate analysis to show how by situating Turkey and Greece in different and also liminal/precarious positions with respect to ‘Europe’, the community-building discourse of the European Union (EU) reinforced and legitimized the two states’ representations of their identities as different from and also as threatening to each other.[27] Barnutz took on the larger question of how a ‘logic of security’ has been constructed in the EU through an analysis of the EU’s discursive practices on security, by employing predicate analysis alongside other tools of discourse analysis.[28] In an influential study, Jackson has shown how the concept of ‘Islamic terrorism’ which became widespread in the West after September 11 was naturalized through certain predicates used in Western political and academic discourse.[29] In his later works, Jackson has utilized predicate analysis, in combination with other methods of discourse analysis, to show how academic discourse in the West has contributed to a certain ‘knowledge’ on ‘terrorism’ serving to reify particular power relations within and between states.[30]

Another discourse analysis method commonly used in the field of international relations and which also treats discourses as systems of signification is ‘metaphor analysis’. In this method, metaphors are conceptualized as ‘structuring possibilities for human reasoning and action’ and are analysed to discover the various regular frames used to make sense of the world.[31] These works did not treat metaphors as ‘objective mediators’ between two pre-established subjects with pre-established similarities.[32] Instead, metaphors were taken to play a crucial role in constructing our knowledge of the world by becoming sedimented in discourse as ‘common sense’ and hence structuring the way we think and act by allowing us to focus more specifically on certain aspects of what is being referred to and excluding alternative ways of thinking and acting beyond the metaphorical constraints.[33]

In metaphor analysis, the international system is conceptualized as a discursive structure which rests on the use of certain metaphors. Language is hereby treated not as a mirror of reality, but as an instrument in its construction. In this sense, metaphor analyses that are employed in international relations studies conceptually overlap to a great extent with other forms of poststructuralist discourse analysis.

Various works of international relations which use metaphor analysis have shown that many of the widespread assumptions in international politics are in fact ‘sedimented metaphors’.[34] For instance, Chilton and Lakoff have argued that international politics have traditionally been built on metaphoric expressions where states are treated as persons or as bounded containers, in turn serving to naturalise certain dominant practices between states and marginalizing others.[35] Others like Little have chosen to focus on a historical analysis of a central metaphor, the ‘balance of power’, which has shaped international relations thinking and scholarship over decades.[36] Milliken has put forward the argument that the reason realist analysts failed to propose alternative policies to the US policy in the Vietnam War, despite their criticism of US policy, was that they viewed international politics through the lens of the same metaphoric structures as the US administration of the time.[37] In a similar vein, Hülsse has argued that the EU has discursively constructed a European identity through its enlargement policy, showing that in cases where the EU’s metaphoric representation as a ‘container’ has been dominant in enlargement policy, the EU has been much less tolerant of identity-based differences situated in culture and religion.[38]

Responding to criticisms that the existing discourse analytical methodologies relying on linguistic tools did not sufficiently address the naturalizing/marginalizing effects of discourse, critical discourse analysis (CDA) brought together analysis of systems of signification with a focus on broader representational practices, and also began to be utilized in the study of international relations.[39] CDA offers linguistic methods that make it possible to empirically analyse the relations between discourse and social and cultural developments in different social domains. CDA approaches in general view discursive practices as an important form of social practice which contributes to the constitution of the social world, including social identities and social relations. CDA broadly shares the concerns of poststructuralist discourse analysis regarding a critical approach to taken-for-granted knowledge, the historical and cultural specificity of discourse, and the role of social interaction in the construction of the world. Nonetheless, it differs from poststructuralist approaches by accounting for non-discursive practices in the construction of social reality. In doing this, it argues for the existence of social reality outside of discourse (such as institutions) in a constant dialectical relationship with discourses.

Although CDA has been widely used in studies of social change and nationalism in the past, its entry into international relations has been more recent. Kryzanowski and Kryzanowski and Oberhuber were among the first to employ CDA in showing how ‘Europe’ is being discursively constructed by EU institutions and EU member states.[40] Tekin employed CDA in displaying the representation of Turkey in French political discourse on EU enlargement.[41] Others, despite CDA’s conceptual differences with poststructuralism, have used the linguistic and argumentative tools of CDA in poststructuralist analyses. Torfing for instance has argued that many of CDA’s ‘analytical notions and categories for analysing concrete discourse and distinguishing between different types and genres of discourse can be used in conjunction with concepts from poststructuralist discourse theories’.[42] Along these lines, Larsen has demonstrated how a specific linguistic tool of CDA (namely the use of the ‘we’ pronoun) could be employed in a poststructuralist study of nation-state foreign policies.[43] Similarly, Aydın-Düzgit has explored the utility of CDA’s analytical tools in both mainstream social constructivist and poststructuralist study of EU foreign policy, while Cebeci and Schumacher have used CDA in showing how the EU represents the Mediterranean.[44]

Among the different strands of CDA, many of the empirical works in this field adhere to the discourse-historical approach (DHA). DHA is a type of CDA that is particularly distinguishable by its specific emphasis on identity construction, where the discursive construction of ‘us’ and ‘them’ is viewed as the basic fundament of discourses of identity and difference.[45] After presenting the historical background and the context of the analysed texts, DHA proceeds in three main steps. The first step involves outlining the main content of the themes and discourses, namely the discourse topics in the narrative on a given subject.[46] The second step explores discursive strategies deployed in the narrative to answer the selected empirical questions directed at the texts.[47] The third step of analysis looks at the linguistic means that are used to realize these discursive strategies.

Following this period of methodological development and diversification, discourse analytical methodologies in IR appear to be entering into a third phase, characterized by greater engagement with quantitative methodologies of textual analysis on the one hand, and internal consolidation on the other. In terms of consolidation, a significant number of textbooks and textbook chapters devoted to discourse analysis in IR have been published in recent years.[48] Consolidation has gone hand in hand with an acceptance of pluralism in discourse analysis. In that vein, Holzscheiter has provided a very useful typology of different types of discourse analysis in IR, distinguishing between interactionist, structural, deliberative, and productive approaches and situating the contemporary discourse analytical scholarship in IR within these types.[49] On the theoretical front, scholars have focused more on the link between discursive and non-discursive realms; practice theory has asserted the unity of the two.[50] The theoretical foundations of discourse analysis in IR have expanded beyond Foucault, Derrida, and Habermas toward more explicit engagement with Lacan, Wittgenstein’s language games, and Laclau and Mouffe.[51]

Alongside these consolidation processes, a number of scholars are attempting to combine discourse analysis with quantitative methods of textual analysis, such as content analysis, while acknowledging the epistemological incompatibilities. In general, content analysts are more comfortable in the positivist assumption of a fixed and objective reality existing independently of the researcher; they seek replicable findings concerning patterns of meaning by measuring the frequency of certain key terms in a large volume of texts. On the other hand, both the more interpretivist and critical variants of discourse analysis question the possibility of objectivity and replicability because they claim that prior understandings of the researchers ultimately shape their interpretations of texts. In addition, they insist on the necessity of in-depth analysis of texts because the same words can denote different things in different social and temporal contexts. Despite these differences, Hardy et al. have argued that content analysis may be used within a discourse analytic approach, by making the social construction of reality and fluidity of meaning shared assumptions of both methodologies.[52] Andrew Bennett argues that computer-assisted content analysis can be a good complement to discourse analysis in identifying the relevant texts, the frequency of certain keywords in greater samples of texts, and patterns of change across different bodies of texts and across time.[53] Hopf and Allan have developed a systematic discourse analysis template which can be used by different researchers to analyse the construction of national identities in different national contexts and across time.[54]

3. Why Did We Choose Discourse Analysis?

Methodology is a critical choice to make in addressing a research topic. Although the authors of this article were trained in different universities in different time periods, they have both chosen discourse analysis as the best methodology to study the identity dimension of EU–Turkey relations and have employed different forms of discourse analysis in their previous and ongoing research.

Bahar Rumelili was introduced to constructivist IR theory during her PhD studies at the University of Minnesota (1996–2002) and was immediately drawn to the study of identity in international relations upon first reading David Campbell’s Writing Security. As she developed her dissertation[55], EU–Turkey relations were at their nadir; the EU’s decision not to consider Turkey as a candidate during its 1997 Luxembourg summit had caused widespread disappointment in Turkey and accusations levelled at the EU that it was excluding Turkey on identity grounds. In order to make this case theoretically relevant for a US academic audience, she built on Iver Neumann’s work on Self and Other in international relations and framed EU/Turkey relations as a case of Self/Other relations. The methodological choice of discourse analysis was a product of her theoretical commitments and the theoretical contribution she sought to make. Alternative methodologies, such as surveys, would not do justice to her conception of identity as socially constructed, relational, and structured by existing structures of meaning. In the late 1990s, there were only a handful of method articles on discourse analysis, and specific methodologies of discourse analysis were yet to be developed. So for methodological guidance, she drew on other studies employing discourse analysis at the time, such as Roxanne Doty’s Imperial Encounters and Karen Litfin’s Ozone Discourses. She focused on identifying different predicates of Self and Other in European Parliament debates on Turkey (1995–2002) and coverage in European and Turkish media of critical developments in EU–Turkey relations. Out of these different predicates, she developed a typology of Self/Other relations that has been adopted by many scholars to make sense of identity relations in other contexts.

Aydın-Düzgit has mainly used critical discourse analysis in her work on identity representations in EU–Turkey relations and European foreign policy[56]—and more recently, on the analysis of the relationship between foreign policy and identity change.[57] Her acquaintance with CDA came at a time when she was beginning to take interest in the role of identity in the EU–Turkey relationship, in the early years of this century when relations between Turkey and the EU intensified after Turkey’s candidacy for membership and the opening of accession negotiations. As she decided to embark on the identification and analysis of the EU’s identity representations in relation to Turkey in her PhD dissertation, the methodology to be utilized became a focal point from the early stages of the research onwards.

While her survey of the literature at the time presented her with different types of discourse analysis potentially suitable to use in her research, her choice of the discourse-historical strand of CDA largely stemmed from her concern with the discursive construction of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomy which is a central focus of this method, the rich analytical toolkit provided by CDA in studying identity representations, and the discourse-historical approach’s emphasis on the historical context, which was highly relevant for the contemporary identity representations in the EU–Turkey relationship. Identity representations in the context of EU–Turkey relations rarely take explicit forms, thus requiring the use of linguistic tools to discern the patterns in representations. As a researcher who lacks specific training in linguistics, Aydin-Düzgit was at first intimidated by the linguistics-inspired analytical toolkit which CDA offers. Thanks to the guidance of her PhD supervisor who was a historian and an expert on CDA, she was introduced at an early stage of her research to a vast array of empirical studies which employed CDA in various fields ranging from political science to history, sociology, media and cultural studies, which helped her overcome this concern. Furthermore, identities can be (re)produced through different genres of texts, which, for the purposes of her research, increased the utility of CDA as a method that takes into account the concept of intertextuality (relations between texts) in the analysis of discourses as well as being applicable across a variety of genres, be it European Parliament and national parliament debates, in-depth interviews, or (as were used in her later work) focus group discussions.

4. How Do We Employ Discourse Analysis Now?

More recently, the two scholars have embarked on a collaborative research project that builds on their shared interests and methodological approach. As part of an EU-funded Horizon 2020 project on the Future of EU–Turkey relations,[58] they examine the identity relations between Europe and Turkey, as these have evolved over two and a quarter centuries. In this section, a brief exemplary discourse analysis from this larger project will be presented.

The project studies cultural and identity interactions between Europe and Turkey from 1789 to 2016 in four key periods in the EU–Turkey relationship (1789–1922, 1923–1945, 1946–1998, 1999–2016). Conceptualizing identity as discursive and relational, it aims at analysing how representations of the European and the Turkish Other varied and evolved through cultural exchanges and political interactions in different historical periods. A number of political and cultural drivers, namely significant historical milestones that have influenced the relationship between Turkey and Europe and that have in turn shaped the mutual perceptions and representations in these given periods, are assigned to selected focal issues, defined as the issues with respect to which Europe (or Turkey) constitutes its identity by comparing itself with and/or differentiating itself from its significant Other. Both the drivers and the focal issues (namely nationalism, civilization, status in international society, and state–citizen relationship) are determined via expert consultation and an extensive literature review.

Concerning text selection, primary sources which encompass a combination of different genres such as memoirs, writings, and private letters of diplomats, other bureaucrats, and intellectuals; newspapers and editorials; literary texts; travel journals; and political speeches are first identified. The texts selected for analysis either explicitly or implicitly illustrate identity discussions on Turkey–EU relations, and reflect the peculiarities of the periods under scrutiny. Further, they are selected with reference to their temporal proximity and relevance to the chosen drivers. DHA, which is a type of CDA, is then employed in discerning the main characteristics of the discursive structures in these texts, and in analysing how they vary over time in terms of their association with the selected focal issues, and in relation to the different cultural and political drivers.[59]

Below we present the discourse analysis of a newspaper article entitled “Is Turkey Part of Europe?”[60] published in the Times in 1964. Here, as in our analysis of each of the texts in this project, we first provide an overview of the historical context, then identify the discourse topics, and finally discuss in detail the discursive strategies of nomination, predication, and argumentation.

4.1. Historical context of the selected text

CDA assumes that all discourses are historical and thus need to be analysed against their context. So the first step in the analysis of a particular text should be situating it in its historical context. The selected article “Is Turkey Part of Europe?” was published by the Times on 1 December 1964. The author of the text is the Ankara correspondent of the newspaper. The publication of the article corresponds with the entry into force of the Association Agreement (also known as the Ankara Agreement) between Turkey and the European Economic Community (EEC) on 1 December 1964. The Agreement aimed towards the establishment of a customs union which was supposed to pave the way for the accession of Turkey into the EEC.

Text 1: “Is Turkey Part of Europe?,” Times [London, England] December 1, 1964, 11, The Times Digital Archive, accessed December 8, 2016.

4.2. Contents and topics of the discourse

The second step is to identify the main topics of discourse in a particular text. In the context of the rapprochement between the EEC and Turkey and the possibility of Turkey’s membership, the author of the article discusses two questions: ‘Is Turkey geographically a part of Europe?’ and ‘Are the Turks Europeans?’. Hence the text is constituted by a discourse on Turkey’s geographical affiliation, but also on Turkish identity in relation to Europe and Europeanness.

4.3 Discursive strategies

Following Reisigl and Wodak, in each text we identify the discursive strategies of nomination, predication, and argumentation.[61]

4.3.1. Referential/nomination strategies

With regard to the discursive construction of social actors, the author only uses a few proper names: s/he refers to ‘the Turkish Foreign Minister Mr. Erkin’, the ‘former Turkish Prime Minister Mr. Menderes’, and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as well as two writers, Marcel Proust and Franz Kafka.

However, the Times correspondent also makes use of many ethnic, national, and religious collectives: Turks, the younger generation of Turks, European people, Europeans, Greeks, Arabs, Hungarians, Finns, Hittites, Armenians, Muslims, young non-Muslim intellectuals, and Christianity. He also refers to the political actors of the European Economic Community and the Council of Europe. Similarly, there is a wide range of ideological anthroponyms such as Turkey’s westernized leaders, inhabitants of modern Turkey, indigenous races, mass of pure Turks, Anatolians, modern Turks, Turkish peasantry, European civilization, and western voices.

In a similar vein, the nomination strategies in the text show a clear binary demarcation between ‘us’ and ‘them’, namely between Europe/Europeans and Turkey/Turks. Binary demarcations not only divide, they also entail an asymmetrical relationship in favour of one component of the divide, which in this context is Europe/EEC/Europeans.

In the context of a possible accession of Turkey to the EEC, the author equates the EEC with Europe and EEC membership with being European. For instance, s/he talks about the consequences of ‘Turkey’s membership to Europe’. Hence becoming a member of the EEC/EU implicates Europeanness on the part of the country in question. At the same time, Europe is constructed as a homogenous entity in relation to the Turkish Other, with no visible scope for diversity. Turkey, on the other hand, is presented as a more heterogeneous entity with a binary community existent within itself, between the European ‘younger generations’ and a ‘mass peasantry’ in Anatolia that cannot be considered European.

4.3.2. Predication strategies

The discursive construction of in- and outgroups usually goes hand in hand with the attachment of positive attributes to the Self and negative ones to the Other. The Times correspondent does not write much about Europe itself, just describing it as ‘united’ in one instance. However, much is said about the outgroup which strives to become part of the European ingroup. The author generalizes that all Turks are Muslims ‘and cannot now be converted to Christianity’. Furthermore, the correspondent states that Turks belong to the ‘white race’. Hence in relation to Europe, Turks are essentialized and homogenized with respect to religion and ethnicity, where their Europeanness is more contested on religious rather than ethnic grounds, and are attributed an overarching wish, particularly on the part of the ruling elite, to become ‘European’.

Subsequently, the writer of the Times article divides Turkish citizens into two subgroups, predicating each differently. The so-called ‘modern Turks’ are considered capable of becoming European; they are described as young, non-Muslim, intellectual, secular, and familiar with Proust and Kafka. This subgroup is attached to positive values because the author considers them as possible members of the ingroup. However, the second subgroup is characterized negatively, even derogatorily. This group consists of a ‘mass of peasantry’ which is religious and ‘escape[s] into the mosques whenever possible’ and thus is not European. Taking identity as a relational concept where representations of the Other entail the conceptions of the Self, these stereotypical predicates provide insight into the imagined content of Europe and Europeanness which excludes practiced Islam and rests on the presence of a white race and a shared intellectual heritage.

4.3.3. Argumentation strategies

The Times correspondent follows two basic argumentation lines in discussing Turkey’s potential accession to the EEC and its Europeanness. One is related to the discourse about Turkey’s geographical affiliation, and the other to the discourse about Turkish identity in Europe.

Concerning Europe’s geographical borders, the author uses the topos of authority to justify the claim that Turkey can geographically be considered a European country. This is done via quoting from a Turkish politician that ‘the frontiers of Europe pass to the south and east of Turkey’, adding that no one was contradicting this statement, and from former prime minister Adnan Menderes, who referred to a newly opened oil refinery in Mersin as ‘the largest oil refinery in Europe’.

Below the subheading ‘No Racial Objections’, the author uses arguments based on essentialist racial discrimination to promote Turkey’s accession to the EEC. The correspondent once again resorts to the topos of authority, with reference to the racial classifications of ethnologists, to justify his/her conviction that Turks are ‘racially Europeans’. Through the topos of comparison, the author rebuts the argument that because Turks originated from the Asian regions they cannot be considered European, by claiming that Hungarians and Finns also originated from Asia.

However, the Times correspondent also distinguishes between two groups of Turks: ‘modern Turks’ and ‘pure Turks’. The former ‘have already ethnically so transmuted themselves over the centuries, by breeding with the indigenous races they conquered, that they are today quite different in almost every way from the mass of pure Turks who inhabit central Asia’. The author uses ‘modern Turks’ and ‘Anatolians’ synonymously and describes them as a distinct ethnic group. By indigenous races, s/he means Armenians and Hittites ‘who may well have been of Aryan stock’ and who inhabited the region before the Turks came to Anatolia.

Following the racial reasoning examined above, religion is the second argumentation strategy used with regard to the identity question. Despite the assumption that ‘Turks are Muslims’, religion does not play an important role in the lives of those ‘modern Turks’ who are ‘deeply committed to Atatürk’s principle of secularism’. The author describes these young Turks as ‘non-Muslim intellectuals’ and regards them as Europeans. Just like ‘us’, this younger generation knows famous Western writers such as Kafka and Proust. However, the article makes clear that practicing Muslims cannot be regarded as Europeans: ‘Of course the mass of the Turkish peasantry, which still seems to escape into the mosque whenever possible, can hardly be regarded as European’. In this sense, such argumentation allows for the discursive construction of ‘Europeanness’ as a trait to be acquired as long as there is no substantive contestation over race and geography, and as long as the essentially European intellectual heritage is adopted.

5. Conclusion

Discourse analytic methods with all their variants face certain similar challenges in displaying representational practices. Any form of discourse analysis requires the existence of texts. The texts selected for analysis differ depending on the research topics and questions adopted by the researcher. Discourse analyses in the field of international relations typically analyse official speeches, declarations, parliamentary debates, diplomatic documents, interviews, newspapers, and editorials as primary documents. In addition to these, other academic works, novels, and conceptual histories can also be analysed. Although less common in international relations, visual materials such as photos and television programmes[62] or ethnographic data[63] can also be put to analysis as forms of multi-modal discourse.

Whichever type of text is selected for analysis, the selection needs to be justified in line with the goals of the research, a key matter which brings us to the issue of sampling in discourse analysis.

Since discourse analysis is largely a qualitative method, the reliability and validity of the analyses cannot be ascertained in exactly the same way as in quantitative approaches. Sampling is usually a common area of criticism directed at discourse analysis. Although most studies analyse typical texts, the definition of typical remains ambiguous and can thus be contested. Sampling may also be based around certain key events and developments concerning the research question at hand. However, there are certain criteria that are offered to increase the reliability and validity of discourse analytic research. DHA, for instance, adopts the principle of triangulation in the analysis of texts. This principle refers to the endeavour to work interdisciplinarily, multimethodically, and on the basis of a variety of different empirical data as well as background information.[64] For instance, in a study on the discursive construction of national identity, the principle of triangulation requires that historical, sociopolitical, and linguistic perspectives on national identity be coupled with an analysis of a wide array of data including political speeches, newspaper articles, posters and brochures, interviews, and focus groups.[65]

It is also crucial that the researcher continues to gather new data until the data reach a saturation point where no new findings are revealed. The ideal analysis would thus require extensive reading from a variety of genres. In practice, it is not possible to read every relevant text on a given issue. What is usually done is to make sure that representations are constantly repeated in a wider textual network and that the analysis and texts are revised upon encountering a text which cannot be accounted for by the discursive positions identified in other analysed texts.[66] It makes the analysis much easier if the analyst already possesses a certain degree of prior knowledge of the general topic of the analysis. This facilitates the identification of meanings that are used in creating common reference points.[67]

Despite these efforts, discourse analytic approaches can still be criticized for not being objective and for engaging in political argumentation rather than rigorous academic research. Yet, the theoretical bases of these approaches generally deny the possibility of full objectivity in the first place. Especially in critical approaches such as CDA, the researcher is not assumed to be purely objective, but instead is entrusted with the task of revealing social mechanisms of oppression, domination, and exclusion through discourse from a critical perspective, provided that s/he is guided by theoretical premises, systematic analysis, and constant self-reflection during the course of the research. Hence the critical dimension in some of these approaches presupposes a certain political stance on the part of the researcher, which points to the crucial significance of self-reflexivity where the analyst does not exist independently of the discursive (and/or non-discursive) context within which society operates. In a similar vein, one other criticism directed at some of these approaches is that they state the obvious. This criticism has been countered by claims that even politically informed individuals may not be able to see through the complex dynamics behind the (re)production and effects of discourse.

Although not a criticism per se, one difficulty that is often voiced especially with reference to CDA is that it requires a certain level of linguistic expertise in the analysis of texts. Indeed, a fundamental difference between CDA and other forms of discourse analysis lies in the former’s emphasis on the micro-level, thus linguistic, analysis of texts. This can be a challenge for scholars coming from different disciplines who would like to apply CDA in their fields of research, and thus in turn imposes an indirect limit on the fields where CDA is employed. Linguistic limitations often limit CDA to individual case studies, because researchers may lack linguistic capacity to study other comparable cases. Nonetheless, the recent successful applications of CDA in fields such as foreign policy and the study of international organizations like the EU demonstrate that this difficulty can be overcome, primarily by an extensive prior reading in empirical studies which employ this method in various different fields.

Our experience with the FEUTURE project has also introduced us to challenges that are more specific to historical forms of discourse analysis. One specific difficulty concerns the issue of censorship. For instance, during our research of the nineteenth-century representations, while we had no problem finding press sources in English, French, and German, press censorship in the Ottoman Empire suppressed evaluative discussion of all domestic and/or international politics in this period. To resolve this issue, we turned to alternative sources which included newspapers published by dissidents outside the Ottoman Empire in Ottoman Turkish as well as private letters, memoirs, and memoranda written by prominent bureaucrats. Historical discourse analysis, by definition, relies heavily on archival research. Besides the problem of censorship, we have sometimes encountered institutional obstacles to accessing the necessary documents. For instance, our universities lacked institutional access to some of the newspaper databases before a certain time, which necessitated collaboration with colleagues from other institutions in different countries. Another challenge was a linguistic one. Particularly in DHA, it is important that all texts are read and analysed in their original languages. In our case, this entailed proficiency in German, French, English, Turkish, and Ottoman Turkish. We managed to overcome this difficulty by working with a team of researchers possessing the necessary linguistic skills (hence also including a historian) for the project. This has shown us the importance of working with an international and interdisciplinary team when undertaking discourse analyses that are ambitious in terms of time and scope. In order to achieve the necessary coordination among members of the team, we developed a common textual analysis template, and conducted periodic meetings.

In sum, since its introduction to the IR discipline in the late 1980s, discourse analysis has developed into an established methodological approach. It is important for IR scholars attempting to analyse textual material, such as speeches and documents, to employ discourse analysis consciously and systematically, taking into account the full range of its theoretical premises and methodological tools.

Adler, E. “Seizing the Middle Ground: Constructivism in World Politics.” European Journal of International Relations 3, no. 3 (1997): 319–63.

Ashley, K. Richard. “Foreign Policy as Political Performance.” International Studies Notes 13 (1987): 51–54.

———. “Untying the Sovereign State: A Double Reading of the Anarchy Problematique.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 17, no. 2 (1988): 227–62.

Aydın-Düzgit, Senem. Constructions of European Identity: Debates and Discourses on Turkey and the EU. London: Palgrave, 2012.

———. “Critical Discourse Analysis in Analysing European Foreign Policy: Prospects and Challenges.” Cooperation and Conflict 49, no. 3 (2014): 354–67.

———. “European Security and the Accession of Turkey: Identity and Foreign Policy in the European Commission.” Cooperation and Conflict 48, no. 4 (2013): 522–41.

———. “Foreign Policy and Identity Change: Analysing Perceptions of Europe among the Turkish Public.” Politics 38, no. 1 (2018): 19–34.

Barnett, Michael, and Raymond Duvall. “Power in International Politics.” International Organization 59, no. 1 (2005): 39–75.

Barnutz, Sebastian. “The EU’s Logic of Security: Politics through Institutionalised Discourses.” European Security 19, no. 3 (2010): 377–94.

Bennett, Andrew. “Found in Translation: Combining Discourse Analysis with Computer Assisted Content Analysis.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 43, no. 3 (2015): 984–97.

Campbell, David. Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

Cebeci, Münevver, and Tobias Schumacher. “The EU’s Constructions of the Mediterranean (2003–2017).” MEDRESET Working Papers no. 3, April 2017. http://www.medreset.eu/?p=13294.

Chilton, Paul. Security Metaphors: Cold War Discourse from Containment to Common House. New York: Peter Lang, 1996.

Chilton, Paul, and George Lakoff. “Foreign Policy by Metaphor.” In Language and Peace, edited by Christina Schaffner and Anita L. Welden, 37–61. Aldershot: Dartmouth, 1995.

Chouliaraki, Lilie. “Spectacular Ethics: On the Television Footage of the Iraq War.” Journal of Language and Politics 4, no. 1 (2005): 143–59.

Diez, Thomas. “Europe as a Discursive Battleground.” Cooperation and Conflict 36 (2001): 5–38.

Doty, Roxanne. Imperial Encounters. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Drulak, Petr. “Motion, Container and Equilibrium: Metaphors in the Discourse about European Integration.” European Journal of International Relations 12, no. 4 (2006): 499–532.

Dunn, Kevin, and Iver B. Neumann. Undertaking Discourse Analysis for Social Research. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

Epstein, Charlotte. “Who Speaks? Discourse, the Subject, and the Study of Identity in International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 17, no. 2 (2011): 327–50.

Hansen, Lene. Security as Practice: Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War. London: Routledge, 2006.

Hardy, Cynthia, Bill Harley, and Nelson Phillips. “Discourse Analysis and Content Analysis: Two Solitudes?” Newsletter of the American Political Science Association’s Organized Section on Qualitative Methods 2, no. 1 (2004): 19–22.

Holzscheiter, Anna. “Between Communicative Interaction and Structures of Signification: Discourse Theory and Analysis in International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 15 (2014): 142–62.

Hopf, Ted. “Identity Relations and the Sino-Soviet Split.” In Measuring Identity: A Guide for Social Scientists, edited by Rawi Abdelal, Yoshiko M. Herrera, Alastair Iain Jonston, and Rose McDermott, 279–315. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Hopf, Ted. Social Construction of Foreign Policy: Identities and Foreign Policies, Moscow, 1955, 1999. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Hopf, Ted, and Bentley B. Allan. Making Identity Count: Building a National Identity Database. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hülsse, Rainer. Metaphern der EU-Erweiterung als Konstruktionen Europäischer Identität. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2003.

Jackson, Richard. “Constructing Enemies: ‘Islamic Terrorism’ in Political and Academic Discourse.” Government and Opposition 42, no. 3 (2007): 394–426.

———. “Knowledge, Power and Politics in the Study of Political Terrorism.” In Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda, edited by Richard Jackson, Marie Breen Smith, and Jeroen Gunning, 66–84. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

Keohane, Robert. “International Institutions: Two Approaches.” International Studies Quarterly 44, no. 1 (1988): 83–105.

Krzyzanowski, Michal. “European Identity Wanted! On Discursive and Communicative Dimensions of the European Convention.” In A New Research Agenda in CDA: Theory and Multidisciplinarity, edited by Ruth Wodak and Paul Chilton, 137–65. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2005.

Krzyzanowski, Michal, and Florian Oberhuber. (Un)doing Europe: Discourse and Practices in Negotiating the EU Constitution. Brussels: P.I.E.-Peter Lang, 2007.

Laffey, Mark, and Jutta Weldes. “Beyond Belief: Ideas and Symbolic Technologies in the Study of International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 3, no. 2 (1997): 193–237.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1980.

Lapid, Yosef. “The Third Debate: On the Prospects of International Theory in a Post-Positivist Era.” International Studies Quarterly 33, no. 3 (1989): 235–54.

Larsen, Henrik. “Discourses of State Identity and Post-Lisbon National Foreign Policy: The Case of Denmark.” Cooperation and Conflict 49, no. 3 (2014): 368–85.

Litfin, Karen. Ozone Discourses: Science and Politics in Global Environmental Cooperation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Little, Richard. The Balance of Power in International Relations: Metaphors, Myths, and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Milliken, Jennifer. “Discourse Study: Bringing Rigor to Critical Theory.” In Constructing International Relations: The Next Generation, edited by Karin M. Fierke and Knud Erik Jorgensen, 136–60. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2001.

———. “Prestige and Reputation in American Foreign Policy and American Realism”. In Post-realism: The Rhetorical Turn in International Relations, edited by Francis Beer and Robert Hariman, 217–38. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1996.

———. “The Study of Discourse in International Relations: A Critique of Research and Methods.” European Journal of International Relations 5, no. 2 (1999): 225–54.

Musolff, Andreas. Metaphor and Political Discourse: Analogical Reasoning in Debates about Europe. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Neumann, Iver B. “Discourse Analysis.” In Qualitative Methods in International Relations: A Pluralist Guide, edited by Audie Klotz and Deepa Prakash, 61–77. Houndsmills: Palgrave, 2009.

———. “Returning Practice to the Linguistic Turn: The Case of Diplomacy.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 31, no. 3 (2002): 627–51.

———. Russia and the Idea of Europe: A Study in Identity and International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

———. “To Be a Diplomat.” International Studies Perspectives 6 (2005): 72–93.

———. Uses of the Other: The East in European Identity Formation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Price, Richard. “A Geneaology of the Chemical Weapons Taboo.” International Organization 49, no. 1 (1995): 73–103.

Reisigl, Martin. “Wie man eine Nation herbeiredet. Eine diskursanalytische Untersuchung

zur sprachlichen Konstruktion österreichischen Nation und österreichischen Identität in politischen Fest- und Gedenkreden.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Vienna, 2004.

Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Antisemitism. London and New York: Routledge, 2001.

Rumelili, Bahar. “Constructing Identity and Relating to Difference: Understanding EU’s Mode of Differentiation.” Review of International Studies 30 (2004): 27–47.

———. Constructing Regional Community and Order in Europe and Southeast Asia. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007.

———. “Liminality and Perpetuation of Conflicts: Turkish-Greek Relations in the Context of Community Building by the EU.” European Journal of International Relations 9, no. 2 (2003): 213–48.

———. “Producing Collective Identity and Interacting with Difference: The Security Implications of Community-Building in Europe and Southeast Asia.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Minnesota, 2002.

Schaffner, Christina. “The ‘Balance’ Metaphor in Relation to Peace.” In Language and Peace, edited by Christina Schaffner and Anita L. Wenden, 75–92. Aldershot: Dartmouth, 1995.

Tekin, Beyza Ç. Representations and Othering in Discourse: The Construction of Turkey in the EU Context. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2010.

Van Dijk, Teun A. Prejudice in Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1984.

Waever, Ole. “Discursive Approaches.” In European Integration Theory, edited by Thomas Diez and Antje Wiener, 163–81. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

———. “Securitisation and Desecuritisation.” In On Security, edited by Ronnie D. Lipschutz, 46–87. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Walker, Rob B. J. Inside/Outside: International Relations as Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Wendt, Alexander. “Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics.” International Organization 46, no. 2 (1992): 391–425.

———. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Wigen, Einar. “Two-Level Language Games: International Relations as Interlingual Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 21, no. 2 (2015): 427–50.

Wodak, Ruth. “The Discourse-Historical Approach.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer, 63–95. London: Sage, 2001.

———. “Introduction: Discourse Studies - Important Concepts and Terms.” In Qualitative Discourse Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by Ruth Wodak and Michal Krzyzanowski, 1–29. London: Palgrave, 2008.

Wodak, Ruth, et al. The Discursive Construction of National Identity, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.