Eric Cox

Texas Christian University

This paper analyzes recommendations made to states under the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in order to determine whether or not the UPR is making meaningful recommendations to states under review. The UPR reviews the human rights of all UN Member States every four years. During the review, each state receives a number of recommendations from other UN member states. This paper uses data from UPR Info to determine if states with better human rights performance as measured by the CIRI human rights data project receive fewer recommendations than states with worse performance. It finds that, even when controlling for other factors, states with worse records on civil and political rights generally receive more recommendations than states with better records. States with lower scores from CIRI on women's economic and political rights receive more recommendations regarding women's issues than states with higher scores. These findings hold regardless of region, suggesting that, at a minimum, the UPR process is identifying violators of human rights.

1.Introduction

On 15 March 2006, the United Nations General Assembly passed General Assembly Resolution A/RES/60/251 to officially create the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC), replacing the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and requiring the HRC to implement a Universal Periodic Review (UPR), a process to regularly review the human rights of every UN Member State. Unlike the process used by treaty bodies such as the Committee against Torture and the Human Rights Committee, the UPR applies to all Member States, regardless of treaty ratifications, and can encompass discussion of any aspect of a state’s rights performance.[1] While the General Assembly required the creation of such a mechanism, the details of the mechanism itself were left to the HRC, which, in 2007, passed A/HRC/RES/5/1 which, among, other things, established the mechanism the UPR would follow. Each year, 42 Member States are subject to review.[2] The UPR process itself was not specified by the General Assembly; rather, the HRC itself created the overall mechanism. As will be discussed below, the mechanism includes self-reports by states, contributions from civil society organizations, statements by other states, and a public discussion of each state’s rights record at which other UN Member States can provide comments or questions to states under review. All Member States have now completed two full reviews. This article examines the nature of the recommendations made to Member States in an attempt to answer the question of whether or not these recommendations reflect states’ actual human rights practices.

Much of the scholarly work on the UPR to date has focused on country or region-specific interactions with the process[3] or a focus on a particular subcategory of rights.[4] More systematic work has been done by the NGO UPR-Info, which is compiling information about the recommendations made under the UPR. Scholars using this dataset have provided more systematic accounts of the UPR.[5] This article uses data from UPR-Info to examine the degree to which recommendations made under the UPR reflect a state’s actual human rights practice. To do so, it examines reports from the first full cycle of the UPR and reviews made through 2014 under the second cycle, totaling 126 additional states.[6] The article finds that a state’s human rights performance does impact the recommendations made to it even when controlling for time, region, and economic size. In short, as a state’s human rights performance gets worse, it receives more recommendations through the UPR. While this article makes no claims regarding whether or not these recommendations lead to improvement in human rights outcomes, the finding that, despite criticisms of the UPR, it is resulting in recommendations being made to states in a manner that is reflective of their human rights performance, is important.

This article will proceed by first providing background on the UPR process itself, followed by a discussion both of existing UPR research and human rights research more generally before presenting the data and conclusions.

2. The Universal Periodic Review

Essentially, the UPR consists of three main stages, an initial review of a state’s current human rights situation, implementation of accepted recommendations, and a report on progress made since the previous review.[7] The review is conducted by the UPR Working Group, which consists of all 47 members of the Human Rights Council. The Working Group then uses three documents to guide the review of a Member State: 1) the State Report, a self-critique submitted by the national government under review; 2) the UN Summary Report, which is organized by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and contains reports of treaty bodies and special procedures concerning the state under review; and 3) the Stakeholder Summary Report, a report compiled by the OHCHR containing additional information provided by appropriate stakeholders, including national human rights institutions, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations.

During the UPR Working Group session, the state under review first presents its national report on the human rights situation in the country. The state under review also has the opportunity to address questions submitted in advance. After the national government’s presentation, an interactive dialogue takes place. During this time, any UN Member State is allowed to ask questions and make recommendations to the state under review. The state under review is then allowed to respond to oral questions, comments and recommendations made. Additionally, the state under review may make specific commitments to improve human rights.

Following the UPR Working Group session, the troika, a committee made up of three Human Rights Council members, prepares the Outcome Report. This document contains a summary of the recommendations made during the UPR Working Group session and the state under review’s responses to those recommendations – states have the option of accepting recommendations, taking them under advisement, or rejecting them. Within two weeks after the Working Group session, the UPR Working Group meets to adopt the Outcome Report. Finally, the UN Human Rights Council must also adopt the Outcome Report before the UPR process is complete.

Over the next four years, the state reviewed has the duty to implement the recommendations contained in the final Outcome Report that it has accepted. According to the OHCHR, “the state has the primary responsibility to implement the recommendations contained in the final outcome.” During the following review of a state, the state must provide evidence of how the recommendations made during the previous review have been implemented.[8]

2.1. Current research

Current reviews of the UPR are mixed regarding its effectiveness, noting both strengths and weaknesses. For example, Human Rights Watch (HRW) noted that early in the process certain states, including Saudi Arabia and Mexico, made either significant commitments to improve specific rights or seriously considered comments from civil society regarding the existing rights conditions in their countries during the process. At the same time, HRW also discusses certain shortcomings, including the weakness of having a review that is essentially conducted by peer states. The problem is that the subsequent review tends to be very general with little meaningful inclusion of human rights experts in the final report of the committee. Additionally, states under review need not provide immediate responses – or any response at all – to suggestions made during the process.[9] Amnesty International echoed these problems early in the process, particularly noting that the quality of the reviews depended in large part on the states under review.[10] The reviews of the UPR by HRW and Amnesty have largely been anecdotal, though they have provided useful insight on individual country reports. They have not released broad data examining trends in the reports.[11]

As noted above, scholars examining the UPR have examined its effectiveness in different ways. Dominguéz Redondo praised the first session of the UPR for working to depoliticize the process, noting the active participation of so many members of the HRC during the interactive dialogue with Member States.[12] Sweeney and Saito, alternatively, expressed frustration with Member States that stacked the speakers’ list during their review session with supporters, thereby limiting the number of critical voices during the process, a frustration echoed by Abebe and McMahon and Ascherio.[13] This theme is also picked up by Davies, who discusses the challenges involved in shifting to a more cooperative approach in dealing with human rights enforcement.[14] A common theme in critiques – and praise – of the new mechanisms is that it is not intended as a review of specific rights practices, but rather is intended to provide advice and assistance to states on how to address human rights concerns.[15]

This early work provided critiques (or support) of the process generally without delving deeply into particular topics or the totality of the review process. More recent works have looked more particularly at the process of the review for particular countries, regions and issues. Smith tests the argument that the UPR treats all states equally. She compares the first cycle review of China and Nauru, finding significant overlap in the countries commenting on their rights practice and the substantive process followed.[16] In a subsequent work, Smith argues that the UPR exposed that the permanent five members of the UN Security Council (the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, France and China), are not paragons of human rights performance as demonstrated by their reviews and that they have not been great champions of the UPR.[17] Landolt uses Egypt’s review to argue that the UPR has provided domestic NGOs a new institutional tool to affect rights discourse and practice in their home country.[18]

Other works have looked at the UPR’s effect on particular categories of rights and the interplay of the UPR with other human rights institutions. For example, Desmond examines the use of the UPR to spread awareness and promote ratification of the UN Migrant Convention,[19] while Patel uses the frame of universalism versus cultural relativism to analyze the approach states have made regarding polygamy in the review process.[20] McMahon, et. al. compare the UPR to the African Peer Review Mechanism.[21] In considering the institutional attributes of the UPR, Baird explores the challenges NGOs in the Pacific region have in being heard in the face of participation by international NGOs that submit more information than the local NGOs.[22] Milewicz and Goodin discuss the capacity of the UPR to improve the deliberative capacity of the UN on human rights issues, including dialogue with states that have poor human rights records.[23] Cowan and Billaud examine the particulars of the three hour review process itself, finding that the manner of review has made it easier for western countries to participate than countries in the developing world, particularly those with limited resources such as small island states. They argue that the UPR is in danger of falling into an “older model of tutelage in which an enlightened West guides a backward non-West in its efforts to ‘catch up’ with the norms that the West has set.[24] Echoing this more ethnographic study, Carraro uses a survey of member state delegations and interviews that find that the UPR is commonly perceived as highly politicized.[25]

Fewer works have taken a more systematic approach to looking at the recommendations as a whole. McMahon and Acherio, in a first cut of descriptive data, provided a breakdown of the number of recommendations made overall, the strength of those recommendations, as well as the responses to them, all broken down by region, work continued by McMahon and Johnson.[26] More recently, Terman and Voeten and Hong have explored specific types of recommendations on a more systematic scale.[27] Terman and Voeten are concerned with the shaming power of rights; in their study they examine the strength of recommendations states make to strategic partners versus other states as well as the types of responses those recommendations generate. They find that states are more lenient with their strategic partners, but also that states under review are more likely to accept recommendations from those partners. Hong finds that both democratic and non-democratic states that have ratified more human rights treaties are more likely to make recommendations encouraging states to make greater commitments to human rights instruments, while only democracies are more likely to call for specific domestic reforms.

The overall picture painted of the UPR is that it is a politicized process beset by many problems, including the possibility that it makes participation by both developing states and NGOs difficult. The larger scale analyses demonstrate that many Member States concur with the view that the process is politicized, and the finding that states are more lenient to their strategic partners (and that states are more willing to listen to strategic partners) does nothing to dispel that possibility. What these studies have not done is to determine whether or not the recommendations made to states under review are reflective of their human rights practice. This article fills that gap by answering the question of whether or not states with worse human rights records receive more recommendations than states with better human rights records.

2.2. Examining the UPR

This article is not making a broad theoretical claim – it is driven by the simple question of whether or not a state’s human rights record impacts the results of its review. If the critics of the UPR are correct and states are able to manipulate the system by arranging for friendly speakers who prevent meaningful discussion of a state’s rights practice, we should see that reflected in the recommendations made to states. In particular, we should find that there is little relationship between a state’s human rights practices and the recommendations made to it during the process. If the proponents of the UPR are correct, we should find that a relationship does indeed exist. This leads to the paper’s primary hypothesis.

H1: A state’s human rights record will have little impact on the number of recommendations made to it during the UPR process.

A second question the paper attempts to answer is related to the first: what kind of recommendations are being made to states? UPR info categorizes each recommendation made on a five-point scale reflecting the reality that not all recommendations call for states to take action; indeed some recommendations actually reaffirm poor human rights practices.[28] It is possible that a state may receive a large number of recommendations, but that many of those recommendations are not serious. For example, if a state is able to stack the speakers’ list with supportive allies, it may receive a large number of recommendations, but a relatively low percentage of action-oriented recommendations. This leads to hypothesis two:

H2: A state’s human rights record will not affect the percentage of action-oriented recommendations it receives during the UPR process.

2.3. Data

To test this hypothesis, this paper analyzes recommendations made during the first cycle of the UPR in which every Member State of the UN – including the most recent member, South Sudan – went under review, and the first 126 reviews under the second cycle.[29] While the UPR quickly evolved during the first several sessions, this study includes all sessions. As will be discussed later, however, the study will introduce a control for earlier sessions in the statistical analysis. The analysis compares a state’s human rights record based on select indicators from the CIRI dataset to recommendations made during the UPR.

To determine how many recommendations states received during the UPR, this paper draws on data from UPR-Info.[30] UPR-Info has catalogued every recommendation made under the UPR through both cycles of the process thus far. Each recommendation is categorized according to the thematic issue covered, the nature of the response to the recommendation, and the type of action recommended. The thematic issue coverage is comprehensive: each recommendation is given at least 1 of 54 tags, and a recommendation that references multiple issues may be given more tags.[31]

To prepare the data for analysis, reports for every country were downloaded. If a recommendation was tagged with multiple issues, I counted it as a recommendation for each issue for which it was tagged. If a recommendation had two tags, it was counted as two recommendations. I then summed the number of recommendations in each category.[32] Finally, I totaled all the recommendations made (using the expanded number), then created a subcategory of civil and political recommendations using a summation of eighteen of the categories used by UPR-Info.[33]

To categorize each state’s human rights performance, I use the CIRI dataset.[34] In particular, I used the Empowerment Rights Index (new) indicator, which sums seven indicators and ranges from 0 (no government respect for these rights) to 14 (full government respect),[35] and created a summative variable from the Women’s Economic Rights and Women’s Political Rights indicators. This indicator runs from 0 (no respect for women’s rights) to 6 (full respect for women’s rights). For all but two states during the first cycle, I used the CIRI indicator for the year prior to their review rather than the year of review under the theory that most information collected for the review will occur prior to the year of the review. The first exception is South Sudan, which first appears in CIRI’s dataset in 2011 – its first year of existence and the year it underwent review. The other exception is Ethiopia. Data for the Women’s Political Rights indicator was missing for the year prior to its review; however, Ethiopia scored a 2 the year before and the year after data was missing. Therefore, I assigned Ethiopia a 2 for that year. For the second cycle, I used data for 2011, the last year for which CIRI data was available.

Finally, each state was placed into its UN region based on CIRI’s categorization. While imperfect, this categorization system uses large enough regions so that each region can be individually analyzed with the exception of North America, which only contains three states. The regions are: Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and Caribbean, North America, and Oceania. While these regions do not overlap perfectly with the UN system of categorization, the two are similar.

2.4. Testing the hypotheses

To test hypothesis one positing that a state’s human rights performance is not associated with the number of recommendations made to a state, this paper uses simple linear regression models. These models are designed to determine if, at a base level, a state’s human rights performance as measured by data from a major human rights index is in any way related to the number of recommendations received by a state.

2.5. Primary independent and dependent variables

Models 1-6 are primarily concerned with civil and political rights. The primary independent variable of interest is the CIRI Empowerment Rights Index mentioned above for the state under review. The dependent variable is the summative total of civil and political rights recommendations rated as a four or five for action for each state under review calculated from UPR-Info’s data. The dependent variable focuses on action-oriented recommendations rather than all recommendations in order to ensure that what is being measured are reasonable critiques of a state’s human rights practice rather than disingenuous or non-specific recommendations made to states so that they can avoid scrutiny.[36] The subset of civil and political recommendations is used rather than using total recommendations as the CIRI Empowerment Rights Index is more concerned with civil and political rights than with other rights covered during the review, including economic and social rights and recommendations related to international institutions.[37]

Models 6-12 are primarily concerned with a similar analysis of recommendations regarding women’s issues. In this case, the summative variable from CIRI for Women’s Economic Rights + Women’s Political Rights is used as the independent variable, with the single category of Women’s Rights from UPR-Info being used as the dependent variable. Models 1-12 are primarily concerned with testing hypothesis one regarding a state’s human rights performance and the number of recommendations it receives.

Finally, Models 13-18 revert to using CIRI’s Empowerment Rights Index as the primary independent variable while using the percentage of recommendations a state receives that are categorized as an action category (receiving a 4 or 5) as the dependent variable. This model tests hypothesis two regarding whether or not a states human rights performance affects its likelihood of receiving a higher percentage of strong recommendations.

2.6. Control variables

Following Achen,[38] this study uses only limited control variables that I have reason to believe may have some impact on the variables of interest. The first set of control variables relates to a state’s relative size and influence in the global community. While it is not necessarily the case that influential states will draw more attention, it is not implausible. For example, in 2010, the United States of America received 507 total recommendations while the average number of recommendations for the other 46 states under review was 222.5. To measure the relative size and importance of a country, two variables will be used: the log of state population and log of state GDP. GDP is used instead of per capita GDP as the control is for the state’s overall size rather than the per capita distribution of wealth. As an example, Luxemburg’s per capita income is approximately three times that of China’s, but I would expect China to draw more attention. For both variables, the number used will be from the year prior to the review, just as with the independent variables from CIRI. These control variables will be used both for the models testing civil and political rights and women’s rights. Both variables are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

The second set of control variables is focused on the regions under review. One criticism noted above of the UPR is that states are able to “stack” the review process with friendly states. We may find that some regions are better able to manipulate the results of the process than other regions, or that regions with higher levels of human rights performance may be more likely to make recommendations related to human rights performance. To address this, a separate dummy variable is created for each region in the CIRI database, scored 0 if the state is not in the region and 1 if it is. A separate model is run controlling for each region other than North America.[39]

A final control variable relates to whether the review was in an early or late session of the UPR. As a new institution, the number of recommendations made in early sessions of the UPR was much lower than in later sessions. For example, in the first session, states received an average of 47.4 recommendations, while by session 4 states received an average of 191.3 recommendations. After a slight dip in session 5 to 176.6 recommendations, the average number of recommendations per session rose above 200 and has been fairly stable. This variable codes the first 8 sessions as 0, while the subsequent sessions studied here (9-21) are coded as 1.

3. Results

3.1. Models 1-6

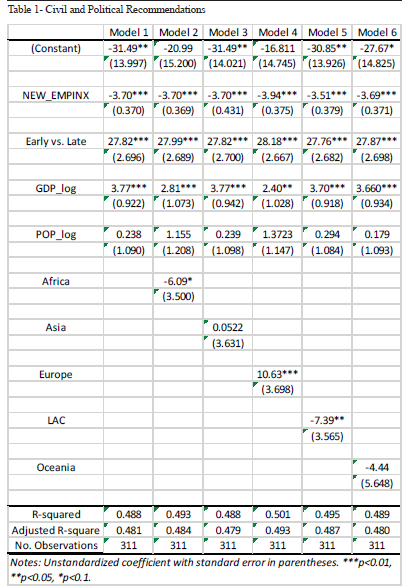

Table one presents results for the first six models which examine the relationship between the Empowerment Rights Index and the number of strong Civil and Political Rights recommendations a state receives. Model 1 contains no regional controls, but does contain the controls for early vs. late sessions, GDP log, and Populations log. Models 2-6 each contain a regional control. No model is run for North America as the region contains only three states.

The way the Empowerment Rights Index is coded, if states with worse records receive more recommendations, the coefficient for that variable should be negative as a higher Empowerment Rights score from CIRI equates to better performance. As can be seen, in each model, the coefficient is negative and is significant at the 99% confidence level. The effect size stays relatively consistent across models; in general, for each point of improvement on CIRI’s scale, a state receives almost four additional recommendations.

Turning to the controls, as expected, states with later reviews receive significantly more recommendations, with a significance at the 99% confidence level in models. Likewise, GDP Log is significant in every model, though the effect is slightly smaller in Europe. Population, on the other hand, is not significant in any model.[40] The most interesting control given criticisms of the UPR are probably the regional controls. African and Latin American States receive significantly fewer recommendations than other regions, while European states receive more. The difference in recommendations for both Asia and Oceania was not significant.

3.2. Models 7-12

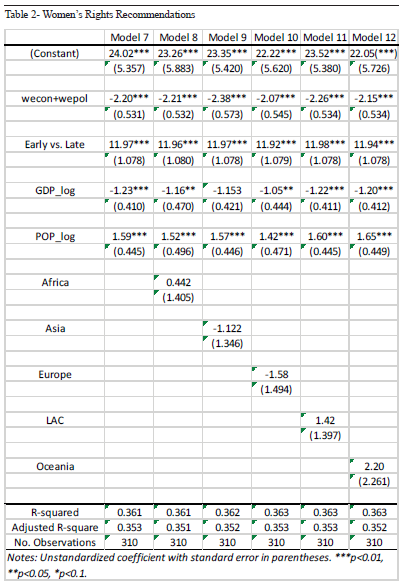

Table two shows results for models 7-12. In each of these models, the primary explanatory variable is the combined Women’s Rights index calculated from CIRI, while the dependent variable is the number of recommendations coded as Women and receiving an action category of 4 or 5 by UPR-Info. All models contain the early vs late, GDP log and Population log controls. As above, models 8-12 each test a different regional control.

The results here are similar to the results in Models 1-6. In every model, the effect of improved women’s rights in the CIRI scale leads to fewer women’s rights recommendations. The controls are somewhat different, however. While GDP is significant for most models, it is not in Model 9 which uses Asia as a control. Interestingly, in every model, the Population log variable is significant and positive, suggesting states with higher populations receive more recommendations regarding women’s rights. No region, however, receives a significantly different number of women’s rights recommendations.

3.3. Models 13-18

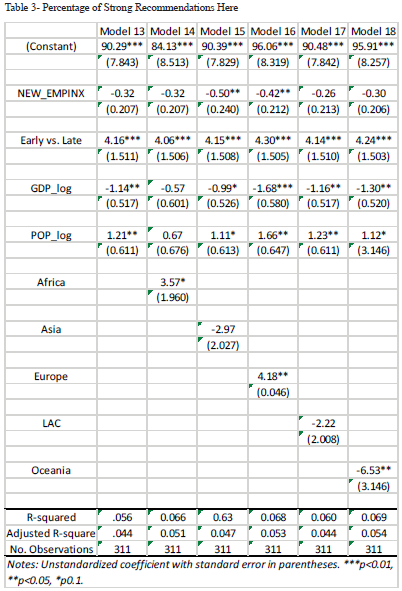

Table three contains results for Models 13-18 which examine the relationship between the Empowerment Rights Index and the percentage of strong recommendations a state receives, introducing the same controls as the previous models. These models have mixed results. While Models 15 and 16 (introducing controls for Asia and Europe respectively), do show that states with a better Empowerment Rights score receive a lower percentage of strong recommendations, the effect is small. The data do suggest that in early vs. late matters in every model, as do both GDP and Population, except in the model looking at Africa. The only two regions that show significance are Africa (Model 14) and Europe (Model 15), both of which have a higher percentage of states receiving strong recommendations at a significant level. Importantly, however, none of these models have a particularly strong fit.

3.4. Discussion

The initial read of the data suggests that the UPR process is providing recommendations to states based on their human rights performance at least to an extent. When looking at civil and political rights in particular, states with a higher score on empowerment rights do receive fewer recommendations, contrary to hypothesis one. The control variables do improve the overall fit of the models addressing civil and political rights, particularly the timing of the session and the size of a state’s GDP. This second variable suggests that states that are larger parts of the global economy may draw more attention than smaller states, consistent with the expected direction of the control variable.

The regional controls also provide mixed news. While a state’s human rights record continues to play a role in determining the number of recommendations a state gets, fears about states “stacking the deck” appear to be supported by the data.[41] African and Latin American states in particular received fewer strong civil and political recommendations than other regions, while European states received more. As noted, however, human rights performance still mattered in determining the number of recommendations a state received.

The data on women’s rights also leads us to reject hypothesis one regarding a state’s human rights performance and the number of recommendations received. In every region, states with better scores from CIRI on women’s rights received fewer women’s rights recommendations in the UPR. Further, in this set of models, no region was significant. Stacking the deck on women’s rights appears not to be occurring. Unlike the civil and political rights models, population was significant, with larger states receiving more attention. At the same time, GDP worked in the opposite direction; states with larger GDPs received significantly fewer recommendations in all models except that controlling for Asia. Any argument about why these two variables operated in separate directions is speculative; while one could surmise that a stronger GDP results in more respect for women’s rights and fewer recommendations, that should be captured by the human rights performance variable and would be better tested using GDP per capita. The control for population, on the other hand, works in the expected direction: larger states receive more attention.

In contrast to the models testing hypothesis one, the models testing hypothesis two find no strong relationship between a state’s human rights performance and the percentage of “strong” recommendations it receives. Even in the models where the variable is significant, the effect is small. While this finding could be discouraging to the idea that a state’s human rights performance leads it to receive stronger recommendations, the finding for this paper does suggests that the absolute number of strong recommendations does go up for states with worse human rights records.

Finally, though the results are not provided here, all the civil and political models were run with a dependent variable using all civil and political recommendations, not just those ranked 4 or 5. All models using women’s rights were similarly run using all women’s recommendations as a dependent variable. The findings were essentially unchanged – states with worse human rights records receive more recommendations.

4. Conclusion and Next Steps

The UPR has not been perfect. In addition to the anecdotal evidence of states attempting to thwart the system or not engage it fully, the process itself has gone through growing pains. Particularly in the early phases of the UPR, few standards appeared to exist as to how to conduct the reviews. Beyond the results reported here, the early outcome reports from the UPR were rarely written in a consistent format potentially leading to considerable inconsistency between reports. Even the writing style used for each report changed over time. Additionally, for the full first cycle and part of the second, states could essentially ignore recommendations or simply choose not to respond. As noted above, this process has already evolved; for example, after the initial sessions the number of recommendations per state began to stabilize.[42] Additionally, the HRC itself has made changes to the process making it more likely that states will engage the recommendations made.

This study also does not consider whether or not the actual recommendations are being implemented. While the NGO UPR-Info released a mid-term report in 2014 that indicated that more than half of accepted recommendations had led to a response by states under review in their mid-term implementation assessments, this report does not necessarily demonstrate that human rights conditions have measurably been improved in states due to the UPR.[43]

The UPR is an imperfect mechanism; its creation was inherently political, a result of the negotiations surrounding the replacement of the Commission on Human Rights. The final review itself is conducted primarily by fellow members of the UN, not necessarily experts, though other stakeholders do have some input. The process itself continues to evolve. Nonetheless, the data presented here suggest that the results of a state’s review do somewhat reflect the actual practice of human rights in a state. Future research should examine the degree to which participation in the UPR and the addressing of recommendations leads to measurable improvement in human rights conditions in member states of the UN.

Abebe, Allehone Mulugeta. “Of Shaming and Bargaining: African States and the Universal Periodic Review of the United Nations Human Rights Council.” Human Rights Law Review 9, no. 1 (2009): 1–35.

Achen, Christopher H. “Let's Put Garbage–can Regressions and Garbage–can Probits Where they Belong.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 22, (2005): 327–39.

Baird, Natalie. “The Role of International Non–Governmental Organizations in the Universal Periodic Review of Pacific Island States: Can “Doing Good” be done Better?” Melbourne Journal of International Law 16, no. 2 (2015): 1–37.

Carraro, Valentina. “The United Nations Treaty Bodies and Universal Periodic Review: Advancing Human Rights by Preventing Politicization?” Human Rights Quarterly 39, no. 4 (2017): 943–70.

Cassayre, Mark. “Statement by the Delegation of the United States of America Delivered by Mark Cassayre.” accessed 9/21, 2018. https://geneva.usmission.gov/2009/06/12/item6unhrc/.

Cingranelli, David L., and David L. Richards. “The Cingranelli and Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Data Project.” Human Rights Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2010): 401–24.

Cingranelli, David L., David L. Richards, and K. C. Clay. “The CIRI Human Rights Dataset. Version 2014.04.14.” Accessed September 21, 2018. http://www.humanrightsdata.com.

Cowan, Jane K., and Julie Billaud. “Between Learning and Schooling: The Politics of Human Rights Monitoring at the Universal Periodic Review.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 6 (2015): 1175–190.

Davies, Mathew. “Rhetorical Inaction? Compliance and the Human Rights Council of the United Nations.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 35, no. 4 (Oct, 2010): 449–68.

Desmond, Alan. “The Triangle that could Square the Circle? The UN International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, the EU and the Universal Periodic Review.” European Journal of Migration and Law 17, no. 1 (2015): 39–69.

Hong, Mi Hwa. “Legal Commitments to United Nations Human Rights Treaties and Higher Monitoring Standards in the Universal Periodic Review.” Journal of Human Rights (2018): 1–14.

Landolt, Laura K. “Externalizing Human Rights: From Commission to Council, the Universal Periodic Review and Egypt.” Human Rights Review 14, no. 2 (2013): 107–29.

McMahon, Edward, and Elissa Johnson. Evolution Not Revolution: The First Two Cycles of the UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review Mechanism. Germany: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2016.

McMahon, Edward, and Marta Ascherio. “A Step Ahead in Promoting Human Rights? the Universal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 18, no. 2 (2012): 231–48.

McMahon, Edward, Kojo Busia, and Marta Ascherio. “Comparing Peer Reviews: The Universal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council and the African Peer Review Mechanism.” African and Asian Studies 12, no. 3 (2013): 266–89.

Milewicz, Karolina M., and Robert E. Goodin. “Deliberative Capacity Building through International Organizations: The Case of the Universal Periodic Review of Human Rights.” British Journal of Political Science 48, no. 2 (2018): 513–33. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000708.

Patel, Gayatri. “How ‘Universal’ is the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review Process? An Examination of the Discussions Held on Polygamy.” Human Rights Review 18, no. 4 (2017): 459–83.

Redondo, Elvira Domínguez. “The Universal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council: An Assessment of the First Session.” Chinese Journal of International Law 7, no. 3 (2008): 721–34.

Smith, Rhona K. M. “‘To See Themselves as Others See Them’: The Five Permanent Members of the Security Council and the Human Right Council's Universal Periodic Review.” Human Rights Quarterly 35, no. 1 (2013): 1–32.

———. “Equality of 'Nations Large and Small': Testing the Theory of the Universal Periodic Review in the Asia–Pacific.” Asia–Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law 12, no. 2 (2011): 36–54.

Sweeney, Gareth, and Yuri Saito. “An NGO Assessment of the New Mechanisms of the UN Human Rights Council.” Human Rights Law Review 9, no. 2 (2009): 203–23.

Terman, Rochelle, and Erik Voeten. “The Relational Politics of Shame: Evidence from the Universal Periodic Review.” Review of International Organizations 13, no. 1 (2018): 1–23.

Víegas–Silva, Marisa. “El Nuevo Consejo De Derechos Humanos De La Organización De Las Naciones Unidas: Algunas Consideractiones Sobre Su Creación y Su Primer Año De Funcionamiento.” Revista Colombiana De Derecho Internacional 12 (10, 2008): 35–66.