Ali Balcı

Sakarya University

İbrahim Efe

Kilis 7 Aralık University

Do leadership attributes change/persist with experience in office, and after a dramatic event? Answers to this agent-structure question represent the main division line between situational and dispositional theorists. While the first posits that leader’s actions are a product of configuration imposed by experience, and traumatic events, the latter focuses on persistent set of beliefs in leaders. This paper aims at testing the role of these two variables, experience, and traumatic event, on the personality of political leaders with a special focus on Recep Tayyip Erdogan. To recover the personality attributes of Erdogan, and measure their resilience or weakness against experience and traumatic events, the paper uses Leadership Trait Analysis (LTA) developed by Margaret Hermann. LTA assumes that leaders’ choice of certain words in public speeches reflects their personality traits, through which they can be compared with other leaders, and even themselves in different roles and times.

1.Introduction

The last decade has witnessed the renaissance of leadership psychology research in the fields of political science and international relations.[1] As part of this renaissance, scholarly publications using assessment-at-distance methods to measure the personality of leaders have burgeoned. This new interest, using large-scale computerized text, pays careful attention to the issue of when and why leaders’ characters change, and undermines the conventional wisdom of political psychology, according to which politicians are driven by consistent attributes.[2] Political psychology scholars have only recently begun to display interest in this topic, amid extensive research on trait changes in social psychology.[3] While one body of research has focused on incremental dynamics such as experience, aging, and learning, others have looked at sudden dynamics such as political shock and role change in order to understand how leaders’ personality attributes change. However, these two sets of variables, incremental and sudden dynamics, have been studied in isolation. It would thus be prudent to examine interactions between these two sets of exogenous dynamics in a similar case.[4]

The theoretical objective of this study, therefore, is to further our knowledge of the role of exogenous dynamics in leadership traits. Inspired by Renshon’s stimulating study of George W. Bush’s strategic and operational beliefs, this paper will empirically evaluate whether situational factors affect the personality traits of political leaders by using the Leadership Trait Analysis (LTA) method.[5] Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the former prime minister and the incumbent president of Turkey, provides an excellent case for a study aiming to measure the effect of experience in office and traumatic events on a leader’s personality attributes.[6] Not only has Erdoğan remained in office for a long time (18 years now), he has even experienced traumatic events of differing magnitudes at various times during his ruling career.

In April 2007, when Erdoğan was relatively less seasoned in office, he was confronted with an e-memorandum from the military (Traumatic Event 1, henceforth TE1), resulting in snap elections in July. Later, during the summer of 2013, he faced a series of demonstrations known as the Gezi Park protests (TE2) after he had gained a considerable amount of experience in office, a time which Erdoğan himself referred to as his ‘master’ (ustalık) period. Finally, the July 2016 military coup attempt orchestrated by the Gulenist cadres in the army led to the deaths of 248 civilians and threatened Erdoğan and his rule (TE3). All of these events were existential threats to Erdoğan’s political survival.[7]

Studying the effect of exogenous dynamics via the case of Erdoğan presents a major methodological challenge, i.e., making generalizations from a single case.[8] The aim of this paper, however, is not to arrive at generalized conclusions about the effects of traumatic events on leadership traits. Rather, it will unearth testable hypotheses regarding exogenous dynamics from the current literature on leadership psychology and bring them to the test in the case of Erdoğan (the congruence method).[9] The paper, then, unfolds as follows. First, it will introduce the LTA methodology and how it is used to measure the change in political leaders’ traits. Second, the related hypotheses are derived from the reviewed literature on the role of traumatic events on leaders’ personalities. Third, the paper will reflect on Erdoğan’s personality attributes and the changing scores of these attributes over time. Finally, the paper will assess theoretical ramifications of the empirical findings.

2. Measuring Change in Leaders’ Traits

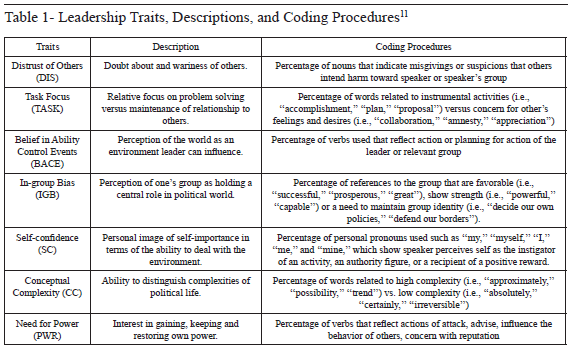

One of the most prominent and enduring techniques for studying political leaders’ personality traits is the Leadership Trait Analysis (LTA) method, developed by Margaret Hermann after decades-long research. Assuming that the personalities of leaders have important effects on foreign policy outcomes, the LTA technique primarily assesses the individual characters of political leaders according to seven traits (see Table 1).[10] In LTA, it is assumed that spontaneous speeches of political leaders (leaders’ instinctive choice of certain words) before the public can reveal the presence of certain personality traits in leaders. The application ProfilerPlus (developed by Social Science Automation) is used to count certain words and phrases leaders use in their interview responses and to determine the individual scores of political leaders in each of the seven traits. In order to interpret the meaning of the results, scores for individual leaders are compared with the average result of 284 world leaders.

Most of the LTA scholarship looks at how specific leadership traits shape leaders’ perceptions of the external environment, crises, and significant events. Reviewing scholarship using at-a-distance techniques for measuring personal characteristics, Kille and Scully come to the conclusion that “strong support now exists for the argument that leaders have particular and identifiable traits that predispose them to behave in certain ways”.[12] Instead of looking at how pre-office variables,[13]such as a leader’s age, gender, military background, business experience, education, and inherited biology, form the traits of leaders, the LTA scholarship measures traits by looking at leaders’ time in office and the effects of traumatic events on leaders, arguing that those traits shape political preferences and outcomes. To cite an example, Yang determines two different stable scores of conceptual complexity for both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Leaving aside the question of how those traits come to be formed, he finds that Clinton’s higher score in conceptual complexity made him open to new information throughout his experience in office, resulting in a change in his previous policy towards China.[14] On the other hand, Bush’s lower score in conceptual complexity made him more vulnerable to traumatic events, causing a fundamental shift in his perception of China after the 9/11 attacks.

Like Yang, the majority of LTA scholars take leadership traits as a casual variable when it comes to the effects of experience in office and traumatic events on foreign policy changes.[15] That means it is neither experience nor a traumatic event that first alters leadership traits to later produce a foreign policy change. Rather, it is some stable leadership traits that make experience or a traumatic event the cause of change in foreign policy. Although Hermann emphasizes the “effects of events and tenure in office” on leadership traits,[16] there is a dearth of systematic LTA studies answering the question of whether a leader’s personality scores (dispositional) are more/less affected by situational factors such as traumatic events or experience in office. Instead of these two factors, recent LTA research has examined the effect of role change on leaders’ personality traits and found that when leaders experience a role change in their political careers, some of their traits undergo statistically significant changes.[17] In addition to role change, the LTA scholarship has also examined the impact of experience and significant events, but only in passing. For example, in their study, based on the assumption that traits are stable, Cuhadar et al.[18] touched on the effect of experience on leadership traits, but they found no significant correlation between change in traits and experience in office.

To assess the effect of exogenous dynamics on leaders’ personality traits, we need fine-grained divisions in time. One approach is to split the time in question into equivalent periods, such as one-year intervals or half-year segments. Another way is to divide time by case, whose effects on leaders’ traits will be measured. Both are found in existing literature in the Turkish context. On the one hand, Cuhadar at al.[19] look at how role changes altered Turkish leaders’ traits and therefore they divide the time according to the moments when role changes occurred. On the other, Gorener and Ucal[20] split the time Erdoğan stayed in office between 2004 and 2009 into one-year intervals to determine whether there have been any changes in Erdoğan’s trait scores as time passes. While the former is useful to measure the impact of significant events on leaders’ traits, the latter is helpful in measuring the change ‘experience in office’ imposes on traits.[21] In addition to these two methods, a comparison between two different groups of years is also useful to assess the impact of experience. For leaders who remain in power long enough, a comparison of the first four years in office with the next four can help with measuring the effect of experience, rendering the role of sudden events irrelevant.[22]

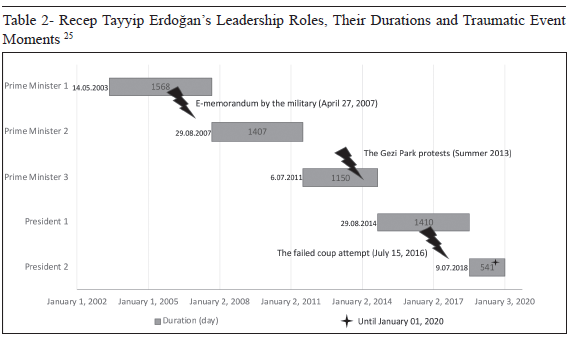

To isolate the effect of traumatic events from other exogenous dynamics such as role change and experience, we use multiple divisions for Erdoğan’s tenure in office. First, we generate two-year groups before and after all three traumatic events in order to measure the effect of traumatic events on the changing traits of Erdoğan.[23] A two-year interval provides ample data for covering a sufficient amount of words, and it also naturalizes the effect of other situational factors such as experience. Second, we divide Erdoğan’s time in office into five groups of years, making it possible to isolate the effects of traumatic events from those of other exogenous dynamics such as experience and role change.[24] Erdoğan served as prime minister from 14 March 2003 to 29 August 2014, more than 11 years in total. Thus, we also split this 11-year period into three intervals according to government changes, because a comparison of Erdoğan’s traits in three different premiership periods will provide useful data to measure the effect of experience. If experience involves changes in leadership traits, we need another measurement design to isolate the effects of traumatic events. Third, we measure together the effects of experience and traumatic events during Erdoğan’s presidency from 29 August 2014 to 24 June 2018. In this specific time span, Erdogan was not only president but also an experienced leader, a factor excluding the effect of role change and time in office. Moreover, he encountered a traumatic event in the middle of this time span. In order to generate two equal intervals before and after TE3, we extend the end of the first presidency term to September 2018 when Erdogan was still the president. All in all, Table 2 demonstrates Erdoğan’s time in office and the three traumatic events occurring during his tenure.

3. Theoretical Framework

In political psychology literature, three exogenous dynamics have attracted the most attention: traumatic events, tenure in office, and role change. With a special focus on traumatic events, we debate the effect(s) of three exogenous dynamics in interaction with each other. In this regard, we define traumatic events as large shocks “in terms of visibility and immediate impact on the recipient”.[26] Rather than as a psychological disorder, we treat “trauma” as a political one that is shattering and “results from human behavior that is politically motivated and has political consequences”.[27] Acknowledging the fact that other significant events can be categorized as ‘traumatic’ and included in the analysis, we have focused on the three aforementioned traumatic events given their relative severity in the context of Turkey.

Political shock stemming from a traumatic event[28] is an experience, however, unlike experience, it occurs in a specific moment. Therefore, it is different from experience acquired from being in office for a period of time. In politics, as Robert Jervis argued in 1976, “sudden events influence images more than do slow developments”.[29] Although Jervis provides historical examples, he does not put his hypothetical argument to an empirical test. Two decades later, Paul F. Diehl, and Gary Goertz[30] looked at the role of “political shocks” at the system and state levels in the beginning and at the termination of rivalries. While they left individual shocks less examined, Diehl and Goertz posit in passing that “some stronger individual shocks are also statistically significant” in explaining the onset and end of rivalries.[31] Before studies using the Operational Code technique were conducted, the linkage between traumatic events and policy decisions remained a hypothetical assumption based on historical narratives.[32] By looking at George W. Bush’s operational code before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Renshon finds that “traumatic shocks do have the capacity to effect fundamental change in individuals’ belief systems”.[33] In a similar vein, by looking closely at how the NATO military exercise ‘Able Archer’ transformed President Reagan’s mental construction of the Soviet Union in November 1983, DiCicco concludes that “dramatic events can help policymakers break free of [their] mental constructs, consequently making possible first step toward peacemaking”.[34]

Both Bush (8 months) and Reagan (less than 2 years) were comparatively less experienced in presidential office when they encountered their respective traumatic events. Although Renshon and DiCicco leave readers uninformed about how traumatic events shape the character or mentality of experienced leaders, we can deduce from their research that leaders with less experience in office are particularly vulnerable to traumatic events. Similarly, Jimmy Carter’s philosophical beliefs underwent a dramatic shift when he faced significant international turmoil, including the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the hostage affair in Iran, during his second year in office.[35]On the other hand, when Helmut Kohl, German chancellor, encountered the fall of communism and German reunification, he had been in office for almost eight years. Closer analysis of Kohl’s belief system indicates that although he shifted his priorities regarding European integration from economic issues to political ones, he continued his pro-European convictions after such traumatic events, resulting in no substantive change in his belief.[36] Similarly, Malici and Malici[37] find that the fall of Soviet socialism had no discernable effect on the control-over-historical-development attribute of Kim II-Sung and Fidel Castro, two long-standing communist leaders.

H1: traits of novice leaders are more vulnerable to traumatic events

Are all leaders the same when it comes to the effect of traumatic events? In other words, what is the relation between leadership traits and traumatic events when the experience variable remains constant? For van Esch, openness to information is logically connected to the level and direction of belief change[38], and thus the lesson drawn from a traumatic event is most likely to change two attributes of a leader, cognitive complexity and self-confidence. Since openness to information largely shapes how leaders make sense of crises, the effect a traumatic event has on a leader is primarily conditioned by traits associated with crisis sense-making.[39] Then, leaders who score higher on conceptual complexity than on self-confidence are open to information, leaving them more vulnerable to traumatic events no matter how experienced they are in office. Rosati, however, finds that being relatively open to new information is not sufficient in itself to produce change in leadership traits.[40]

H2: leaders open to new information are likely to change after traumatic events.

Renshon, in his study of the former US President George W. Bush, finds that traumatic events can permanently alter fundamental attributes of leaders, rather than simply causing a fleeting shift.[41] This finding indicates that leaders who continue to stay in office do not change their attributes imposed by traumatic events. According to Renshon’s findings, experience can only change leaders’ scores on the control-over-historical-development attribute, which is interestingly resistant to traumatic events.[42] On the other hand, Ziv finds that interaction with information flows over time and learning in office leads political leaders to better internalize this information, and in turn, reassess their beliefs.[43] This happens because a significant amount of disconfirming evidence indicates that the preferences resulting from a traumatic event may not be having the desired effect.[44] Therefore, traits consolidated by experience are the main obstacle before learning from traumatic events. These two findings, taken together, propose that when traits are influenced by experience or a traumatic event, they become more resistant to new exogenous factors.

H3: traits once changed by exogenous factors are more resistant to new situational effects.

4. Measuring Erdoğan’s Leadership Traits

In gathering and assessing data, the LTA scholarship follows specific guidelines.[45] First, the LTA scholars select data from media interviews and Q/A sessions of a press conference, both of which are spontaneous. Second, those spontaneous speeches, available from different sources such as newspapers’ archives, leaders’ webpages, and transcripts of TV interviews, are collected. Third, if the leaders are non-English speaking, one can collect their English-translated responses to questions in interviews and press conferences across his time in office.[46] Finally, an adequate analysis requires at least 5000 words from those sources. When the data collection is complete, researchers use ProfilerPlus, developed as a computerized ‘at-a-distance’ method, for the assessment of leadership traits. This computerized program calculates each leadership trait according to a coding scheme and gives them a value between 0 and 1; the higher the value, the more leaders exhibit one trait. At this point, researchers focusing on change in traits through time use ‘t-tests’ and ANOVA in order to assess if changes in scores are statistically significant.[47]

To measure all leadership traits of Erdoğan, his responses to questions in interviews and press conferences from March 2003, when he was elected to the parliament, until September 2018, were collected. The data was retrieved from Lexis Nexis with the search terms “Erdoğan” and “interview”. In addition, independent research was conducted to find interviews absent in the Lexis Nexis search. This data-gathering process resulted in an initial corpus of more than 70 million words that had to be downsized. A group of 7 research assistants and a researcher scanned all of the data to retrieve the most pertinent segments. Only interviews and Q/A sections of press conferences with President Erdoğan were included in the data in order to reduce the potential effects of speechwriters on the usage of language. The interviews were coded according to date considering that the primary aim of this study is to compare Erdoğan’s scores across his time in office. Eventually, we compiled a corpus consisting of interview transcripts from March 2003 to September 2018, amounting to a corpus of 202,724 words. 204 texts were included in the corpus. Since the paper’s primary objective is to assess whether the changes in Erdoğan’s scores across time are statistically significant, a t-test was employed to analyze the data.

5. Results and Discussion

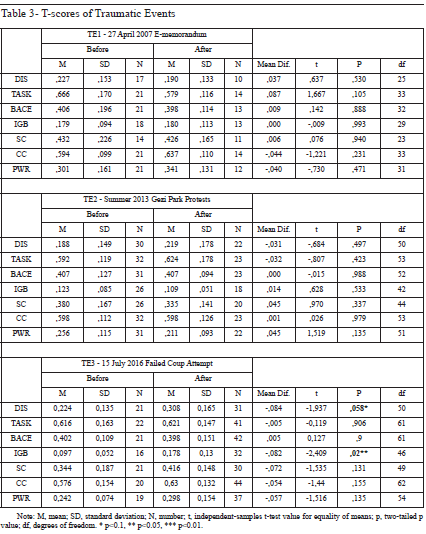

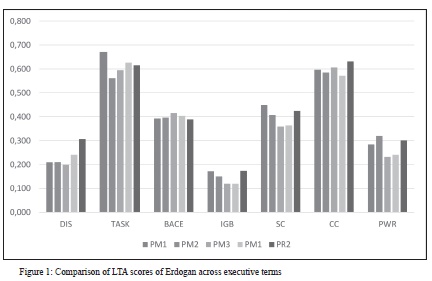

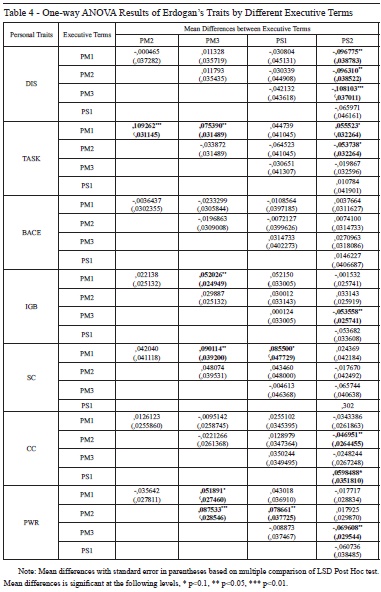

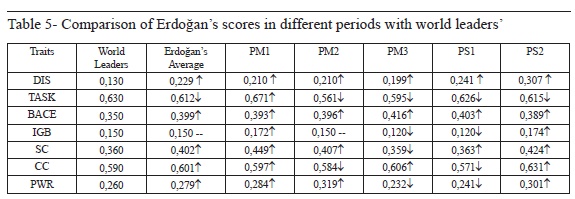

To measure the effect of the selected traumatic events on the leadership traits of Erdoğan, we generated four different charts below. The first one (Table 3) contains trait scores calculated according to the effect of three traumatic events (TE1, TE2, and TE3). The table presents before and after scores for each traumatic event in order to show which traumatic event changed Erdoğan’s trait scores by a significant margin. The second (Figure 1) and third charts (Table 4) include trait scores calculated according to five different groups of years (PM1, PM2, PM3, PS1, and PS2). Variances among three groups of years (PM1, PM2, and PM3) show the effect of experience because these three periods are neutralized from both role change and traumatic event. If TE1 and TE2 had no effect on Erdoğan’s traits, this might be because his traits remained stable during the period in question. If we find any effect of experience and role change on his traits, this may increase the confidence level of our findings about TE1 and TE2. The last chart (Table 5) compares Erdogan’s trait scores in different periods with the average scores of world leaders.

Table 3 shows that TE3 changes two different traits (DIS, and IGB) on a statistically significant scale. This finding has four significant implications for the hypotheses set out in this paper. First, the findings in Table 3 reveal that the magnitude of TE3 is comparatively higher than the other two because only this traumatic event has a significant effect on Erdoğan’s traits. More importantly, only TE3 is confirmed as a traumatic event while our preliminary assumption that TE1 and TE2 are also traumatic remains unconfirmed. Second, the results of the analysis of TE3 show that traumatic events can dramatically influence traits of political leaders with a long experience in office. This finding clearly contradicts H1 positing that expert leaders are impregnable against traumatic events. Third, the results in Table 3 partly refute H3 because traits imposed by experience (see Figure 1 and Table 4) are dramatically changed by TE3. Moreover, in the case of IGB, the more a trait is influenced by time in office, the more it is displaced by TE3. Table 3, however, does not provide enough data to test whether traits imposed by traumatic events are altered by time in office simply because we do not observe any change in trait scores as a result of TE1 and TE2.

The last implication is about H2. In three groups of years, including 2 years before TE1, 2 years after TE1 (see Table 3), and five years during PM1 (see Figure 1), novice Erdoğan’s scores for CC are higher than his scores for SC, making him open to new information. Also, the fact that his average scores for both CC and SC during the periods in question are higher than the scores of world leaders again makes Erdoğan open to new information. Therefore, our results seem to contradict H2 because TE1 has no significant effect on Erdoğan’s traits, despite his openness to new information. Since Table 3 does not confirm that TE1 is a traumatic event, however, it may be misleading to judge from these results whether novice leaders open to new information are more vulnerable to traumatic events. On the other hand, the findings in Table 3 confirm H2 because TE3 alters some traits of Erdoğan, who maintained his openness to new information during his late time in office. But unlike van Esch’s findings, TE3 has no effect on traits associated with a leader’s openness to new information, namely conceptual complexity and self-confidence.[48]

Score variances in three premiership periods as shown in Figure 1 and Table 4 suggest that leadership traits are influenced by time in office. Four leadership traits of Erdoğan, TASK, IGB, SC, and PWR, undergo significant changes in the absence of a traumatic event and role change. Figure 1 and Table 4 also show that BACE and CC are the most robust traits against the effect of experience. The score of SC steadily decreases as Erdoğan gains experience. The t-test for the SC scores of PM1 and PM3 shows that there is a statistically significant change (p=0,023, p<0.05) as a result of spending time in office (Table 4). Although TASK and PWR undergo significant variations from one period to another during Erdoğan’s premiership (Table 4), the effect of experience is not in one direction (Figure 1). Therefore, we cannot easily attribute variations in TASK and PWR to the effect of experience.

Figure 1 and Table 4 are also telling more about PWR. When we exclude PM1, we observe that scores steadily decrease from PM2 to PM3 and from PM3 to PS1 (Figure 1), and changes from PM2 to PM3 and PS1 are statistically significant (Table 4). Unlike 2 years before and after comparison (Table 3), Table 4 also shows that TE3 changes experience-imposed scores of PWR during PM3 and PS1. From this, we can infer that experience and traumatic events have opposite effects on PWR scores, as in IGB and SC. The PM3 and PS1 scores of PM3 and PS1 periods for IGB, SC, and PWR are moved back to the scores of novice Erdoğan after the traumatic event of the 15 July coup attempt. Therefore, changes imposed by experience are not resistant to the effect of traumatic event, rendering H3 unconfirmed.

In view of the above findings, it appears that the interpretation approach to LTA scores in most of the existing studies are problematic simply because scores that ignore one of the two exogenous dynamics, traumatic event and tenure in office, might be misleading. If these two exogenous dynamics have a significant effect on traits as this study reveals, it is misleading to use average trait scores for leaders who stay in power for a long period of time. To test this, we generate Table 5, comparing average scores of Erdoğan with his scores in different periods. For example, if we use Erdoğan’s average scores in explaining his political decisions during the periods of PM3 and PS1, we will expect Erdoğan’s scores in IGB and PWR to be higher than those of world leaders. However, his scores for IGB and PWR are lower than those of world leaders when we look at these two periods. Depending on which scores we use, our inferences about Erdoğan’s decisions will be completely different. Therefore, the main task for LTA scholars is to solve the problem stemming from the tension between dispositional and situational effects.

6.Conclusion

Recent scholarship has shown convincingly that foreign policy change is not solely determined by international and domestic factors, but also by the prism of individual leaders’ personal beliefs.[49] Instead of explaining policy change by comparing leaders in power with their predecessors or successors,[50] this study posits that personality shifts in a specific leader can lead to varying analytical implications. When a leader’s behavior is studied over time, however, stable traits fall short of explaining why the same leaders behave remarkably differently. Therefore, it is misleading to attribute fixed traits to leaders, especially those who stay in office for relatively long periods of time, leaving the change in foreign policy preferences in the course of an incumbent’s term of office inadequately explained. In the case of Erdoğan, our findings prove that using the average scores of political leaders who stay in office for a long time and experience a traumatic event can be misleading. Instead of viewing traits as situation-free, LTA scholars should allow for the effects of experience and traumatic events as exogenous dynamics alongside role change.

Where might these new scores of traits originate? This paper looked at the most ‘formative’ factors in office, experience and traumatic events. However, as traits are also formed by pre-office factors in complicated and nonlinear ways, change in leaders’ traits during their time in office might be influenced by numerous factors at play in a complicated way. Family affairs of incumbent leaders might be more important than traumatic events experienced in political life. If leader age does matter as some studies have proven, getting older in office makes the impact tenure has on traits more complicated. [51] In methodological terms, this leaves us with two challenging tasks. On the one hand, it is a herculean task to put all factors in an empirical analysis. The main task of future studies, then, is to determine which situational factor is more relevant. However, the effect of exogenous dynamics is not free of dispositional traits. Leaders with specific characters might be influenced more by some situational factors. This is the second challenge for future studies.

Dispositional (focusing on leaders’ cognitive properties) and situational (looking at leaders’ differing environments and background experiences) studies in political psychology within the IR discipline occasionally talk to one another.[52] However, a study of leaders’ dispositional traits together with leader-level situational variables can demonstrate that the dispositional characteristics of leaders are fluid rather than fixed.[53] Especially for leaders who remain in power for a long time, the combination of dispositional traits with situational factors can provide a deeper understanding of leadership personality. Although this finding is based solely on the case of Erdoğan, the effect of situational dynamics on dispositional traits can be tested by new studies examining traits of leaders who stay in office for a very long time, such as Vladimir Putin of Russia and Angela Merkel of Germany. Such new research may not only test results from the Erdoğan case, but can also potentially update the relevance of some hypotheses in this paper and add more important ones into the hypothesis catalogue.

Acknowledgement

Bak, Daehee, and Glenn Palmer. “Testing the Biden Hypotheses: Leader Tenure, Age, and International Conflict.” Foreign Policy Analysis 6, no. 3 (2010): 257–73.

Bleidorn, Wiebke, Christopher J. Hopwood, and Richard E. Lucas. “Life Events and Personality Trait Change.” Journal of Personality 86, no. 1 (2018): 83–96.

Boin, Arjen, Bengt Sundelius, and Eric Stern. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Cagaptay, Soner. The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey. London: IB Tauris, 2017.

Cuhadar, Esra, Juliet Kaarbo, Baris Kesgin, and Binnur Ozkececi‐Taner.“Changes in Personality Traits and Leadership Style Across Time: The Case of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting, International Society of Political Psychology, Edinburgh, 29 June -3 July 2017.

———. “Examining Leaders’ Orientations to Structural Constraints: Turkey’s 1991 and 2003 Iraq War Decisions.” Journal of International Relations and Development 20, no. 1 (2017): 29–54.

———. “Personality or Role? Comparisons of Turkish Leaders Across Different İnstitutional Positions.” Political Psychology 38, no. 1 (2017): 39–54.

DiCicco, Jonathan M. “Fear, Loathing, and Cracks in Reagan’s Mirror Images: Able Archer 83 and an American First Step toward Rapprochement in the Cold War.” Foreign Policy Analysis 7, no. 3 (2011): 253–74.

Dille, Brian, and Michael D. Young. “The Conceptual Complexity of Presidents Carter and Clinton: An Automated Content Analysis of Temporal Stability and Source Bias.” Political Psychology 21, no. 3 (2009): 587–96.

Dyson, Stephen Benedict. “Alliances, Domestic Politics, and Leader Psychology: Why Did Britain Stay out of Vietnam and Go into Iraq?” Political Psychology 28, no. 6 (2007): 647–66.

———. “Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling, and the Great Financial Crisis: Leadership Traits and Policy Responses.” British Politics 13, no. 2 (2018): 121–45.

———. “Personality and Foreign Policy: Tony Blair's Iraq Decisions.” Foreign Policy Analysis 2, no. 3 (2006): 289–06.

Erisen, Cengiz. “The Political Psychology of Turkish Political Behavior: Introduction by the Special Issue Editor.” Turkish Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 1–12.

Feng, Huiyun. “The Operational Code of Mao Zedong: Defensive or Offensive Realist?” Security Studies 14, no. 4 (2005): 637–62.

George, Alexander L. Presidential Decision-making in Foreign Policy: The Effective Use of Information and Advice. Boulder: Westview Press, 1980.

George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

Goertz, Gary, and Paul F. Diehl. “The Initiation and Termination of Enduring Rivalries: The Impact of Political Shocks.” American Journal of Political Science 39, no. 1 (1995): 30–52.

Goldsmith, Benjamin E. Imitation in International Relations: Observational Learning, Analogies, and Foreign Policy in Russia and Ukraine . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Görener, Aylin Ş., and Meltem Ş. Ucal. “The Personality and Leadership Style of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan: Implications for Turkish Foreign Policy.” Turkish Studies 12, no. 3 (2011): 357–81.

Gustavsson, Jakob. “How Should We Study Foreign Policy Change?” Cooperation and Conflict 34, no. 1 (1999): 73–95.

Hafner-Burton, Emilie M., D. Alex Hughes, and David G. Victor. “The Cognitive Revolution and the Political Psychology of Elite Decision Making. ” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 2 (2013): 368–86.

Hermann, Charles F. “Changing Course: When Governments Choose to Redirect Foreign Policy.” International Studies Quarterly 34, no. 1 (1990): 3–21.

Hermann, Margaret G. “Assessing Leadership Style: A Trait Analysis.” In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders, edited by J. M. Post, 178-212. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2003.

———. “Explaining Foreign Policy Behavior Using the Personal Characteristics of Political Leaders.” International Studies Quarterly 24, no. 1 (1980): 7–46.

———. “William Jefferson Clinton’s Leadership Style.” In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders, edited by J. M. Post, 313–23. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Horowitz, Michael, Rose McDermott, and Allan C. Stam. “Leader Age, Regime Type, and Violent International Relations.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 5 (2005): 661–85.

Horowitz, Michael C., and Matthew Fuhrmann. “Studying Leaders and Military Conflict: Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 10 (2018): 2072–086.

Jervis, Robert. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Johnston Conover, Pamela, and Stanley Feldman. “How People Organize the Political World: A Schematic Model.” American Journal of Political Science 28, no. 1 (1984): 95–126.

Keller, Jonathan W. “Constraint Challenger, Constraint Respecter, and Crisis Decision Making in Democracies: A Case Study Analysis of Kennedy versus Reagan.” Political Psychology 26, no. 6, (2005): 835–66.

Kertzer, Joshua D. Resolve in International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Kertzer, Joshua D., and Dustin Tingley. “Political Psychology in International Relations: Beyond the Paradigms.” Annual Review of Political Science no. 21 (2018): 319–39.

Kille, Kent J., and Roger M. Scully. “Executive Heads and The Role of Intergovernmental Organizations: Expansionist Leadership in the United Nations and the European Union.” Political Psychology 24, no. 1 (2003): 175–98.

Malici, Akan, and Johnna Malici. “The Operational Codes of Fidel Castro and Kim Il Sung: The Last Cold Warriors?” Political Psychology 26, no. 3 (2005): 387–412.

Nye, Joseph S. “Nuclear Learning and U.S.-Soviet Security Regimes.” International Organization 41, no. 3 (1987): 371-402.

Preston, Thomas. The President and His Inner Circle: Leadership Style and the Advisory Process in Foreign Policy Making. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Renshon, Jonathan. “Stability and Change in Belief Systems: The Operational Code of George W. Bush.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52, no. 6 (2008): 820–49.

Rosati, Jerel A. “Continuity and Change in the Foreign Policy Beliefs of Political Leaders: Addressing the Controversy over the Carter Administration.” Political Psychology 9, no. 3 (1988): 471–505.

Roberts, Brent W., Jing Luo, Daniel A. Briley, Philip I. Chow, Rong Su, and Patrick L. Hill. “A Systematic Review of Personality Trait Change through Intervention”. Psychological Bulletin 143, no. 2 (2017) 117–41.

Shannon, Vaughn P., and Jonathan W. Keller. “Leadership Style and International Norm Violation: The Case of the Iraq War.” Foreign Policy Analysis 3, no. 1 (2007): 79–104.

Tetlock, Philip E. Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Van Esch, Femke. “A Matter of Personality? Stability and Change in EU Leaders’ Beliefs During the Euro Crisis.” In Making Public Policy Decisions: Expertise, Skills, and Experience, edited by D. Alexander and J. M. Lewis, 53–72. London: Routledge, 2014.

———. “Why Germany Wanted EMU: The Role of Helmut Kohl's Belief System and the Fall of the Berlin Wall.” German Politics 21, no. 1 (2012): 34–52.

Vertzberger, Yaacov Y.I. “The Antinomies of Collective Political Trauma: A Pre‐Theory.” Political Psychology 18, no. 4 (1997): 863–76.

Walker, Stephen G., Mark Schafer, and Michael D. Young. “Systematic Procedures for Operational Code Analysis: Measuring and Modeling Jimmy Carter's Operational Code.” International Studies Quarterly 42, no. 1 (1998): 175–89.

Yang, Yi Edward. “Leaders’ Conceptual Complexity and Foreign Policy Change: Comparing the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush Foreign Policies toward China.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 3 (2010): 415–46.

Yavuz, M. Hakan, and Bayram Balci. Turkey's July 15th Coup: What Happened and Why. Salt Lake: Utah State University Press, 2018.

Ziv, Guy. “Simple vs. Complex Learning Revisited: Israeli Prime Ministers and the Question of a Palestinian State.” Foreign Policy Analysis 9, no. 2 (2013): 203–22.