Hakan Mehmetcik

Marmara University

Hasan Hakses

Selcuk University

Global International Relations (IR) research promotes more spaces for a broader spectrum of histories, insights, and theoretical perspectives beyond the conventional dominant Western ones in the IR discipline. The primary goal of this paper is to highlight that the study of Regionalism has a significant role in supporting the initiative of ‘globalizing IR’ by representing a sub-discipline that is open to new ideas, theories and methods, especially those emanating from non-Western contexts. As such, Regionalism is one of the sub-disciplines of IR and International Political Economy (IPE) with a tremendous potential to showcase global-IR trends. This article utilizes a bibliometric analysis as a proxy for mapping out the diverse and complex intellectual structure of Regionalism as a sub-discipline of IR. Our findings indicate that the remarkable rise in the total number of contributions from non-Western scholars to the Regionalism literature in the last decade suggests that unlike the theory generating mainstream studies Regionalism studies have become dominated by non-European/non-Western contexts.

1. Introduction

International Relations (IR) is largely accepted as a science rather than an art, even though there is no strong consensus about what the field/discipline might constitute.[1] When IR is considered a social science discipline, two points draw our attention. The first is that the discipline contains debates on almost any topic, rather than having general integrity or harmony. Indeed, we see that this extends even to debates over the very meaning of discipline itself.[2] What is IR? What should the core field of interest and unit of analysis be? Who or what are the major actors in world politics? At what levels should we perform our analyses of these actors? Where do we draw the boundaries between IR and other social sciences, such as history, political science or economics? Finally, where should we look to find the origins of this discipline? These are the first few questions that come to mind in defining IR as a field of social inquiry. Since these controversies are so ubiquitous in the discipline, “IR scholars clarify the theoretical evolution of the discipline through major debates (Great Debates) whose very existence is not entirely clear”.[3] Based on these and many other related debates, we may refer to IR as ‘a discipline of debates’.[4]

Secondly, aside from its argumentative nature, the field seems to be an American social science.[5] One dimension of this claim is about its unhealthy and biased structure in regarding the production of theories (knowledge claims) or the ‘privileg[ing of]] epistemic ways of knowing’ (methodologies).[6] Despite almost half a century of attempts at reducing American-centrism in the discipline, American IR remains a global agenda-setting force.[7] Via a sequence of constantly repeated narratives, the prevailing academic orthodoxy has made IR incapable of opening spaces for non-western inferences.[8] In this structure, American and European academics are responsible for the development of concepts and theories, while the burden of providing case studies and testing theories in non-Western contexts is carried out by others. Similarly, global agenda-setting—the process of originating, legitimizing and successfully lobbying for a specific policy issue in the economic or security realm—is widely perceived as a Western-only activity. Non-Western thought is rarely regarded as a viable source for constructing authentic IR knowledge.[9] That is, the American/Western theorists set the agenda by having a privileged position that amplifies their epistemic voice in deciding what knowledge is useful for IR and how we can (re)produce it. In Acharya’s words:

IR scholarship has tended to view the non-Western world as being of interest mainly to area specialists, and hence a place for "cameras," rather than of "thinkers" for fieldwork and theory-testing or “when considering the ideas that have shaped IR thinking, why do we make so much of Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, and Kant, but not Ashoka, Kautilya, Sun Tzu, Ibn Khaldun, Jawaharlal Nehru, Raul Prebisch, Franz Fanon, and many others.[10]

In addition to this type of Eurocentrism,[11] there are exclusionary practices that also manifest themselves in the arbitrary publication standard-setting, gatekeeping, and the marginalizing of alternative narratives, ideas, and methodologies.[12] Overall, IR is a fragmented discipline and its fragmentation is frequently attributed to intra-disciplinary differentiation along epistemological, theoretical, methodological, topical and national/regional dividing lines.[13] Although more diversity and plurality dominate IR today than did in the years when the discipline first developed in the early 1920s, there is still much to do in order to address such examples of ethnocentrism and exclusion.[14]

Global IR, sometimes referred to as Non-Western IR or post-Western IR, is one of the important visions in IR scholarship in its departure from the practices of eurocentrism, ethnocentrism and exclusion.[15] Global IR scholars’ point of departure is instigated by the IR discipline itself being too Western-centric.[16] Global IR scholars aim at facilitating greater inclusivity and diversity in IR by opening up spaces for a broader variety of histories, perceptions and theoretical insights, particularly those beyond the West. [17] Therefore, Global IR is not a theory, but rather an aspiration. Acharya notes that the key challenge for Global IR scholarship in this vision is to develop original homegrown concepts and approaches and to apply them to other contexts, including Western cases,[18] which overall requires going beyond the ideal types of normative reference points provided by Western typologies, conceptions and theories.

Global IR is also an aspiration for a more diverse and plural discipline that goes beyond the unequal and unjustified division of labor (theory building in the West, theory testing in the Rest), and it envisages an agenda-setting role for non-Western scholarship. There has been a growing awareness of, and discontent with, the limited and Euro-American–centric framing of dominant ideas in IR.[19] In this sense, Regionalism is one of the sub-fields that epitomizes the Global IR aspiration in real life, as ‘regional worlds’ provides a better understanding of global politics by bringing many diverse insights, practices and perspectives into IR.[20] In view of globalizing/pluralizing/diversifying the disciplinary agenda, regional worlds are ‘broader, inclusive, open and interactive’. Hence, the concept of ‘regional worlds’ is not only a demand for increased attention to regions but also a critical step toward a better understanding of world politics by highlighting the diverse experiences and perspectives of various actors on the international stage. In a way, Regionalism serves as a means for expanding and enhancing existing knowledge, including concepts, methodologies and empirical underpinnings. [21]

When Regionalism first appeared as an intellectual sub-field in the aftermath of the Second World War,[22] it was more about ‘European Integration’ than anything else.[23] Though the European experience has been essential to the study of Regionalism, both history and modern practices demonstrate that it is not the only model to draw upon.[24] Retrospectively, Latin American, Middle Eastern or Asian Regionalism have earlier roots compared to the European journey. Following their independence in the nineteenth century, South American nations were among its early supporters. One of the first works on Regionalism was written not by a European, but by an Indian academic.[25] In 1945, there were only two regional organizations in the world (the Southern African Customs Union established in 1910 and the Arab League established in 1945). Despite the fact that research and practice on European regionalism is one of the most significant and elaborated on in Regionalism studies, Regionalism Studies are not a uniform, unique or linear process; rather, it has evolved through phases, influenced by a variety of causes and actors. Rather than solely studying European integration, since the 1990s many researchers have intentionally included non-European contexts and cases, seeing them as more relevant to the study of Regionalism.[26] Accordingly, Regionalism as a practice and theory has since grown into a truly diverse and complex phenomenon with contributions from different parts of the world. Thus, the non-Western world also has a greater influence on the Regionalism literature by making significant contributions to the discipline.

The remainder of the article discusses why Regionalism is an exemplary sub-field in terms of globalizing IR studies. This is achieved by way of reviewing the literature on Regionalism and conducting an empirical analysis with the use of bibliometric data collected from the Web of Science (WoS) database.

2. Regionalism as a Practice and a Field of Study

As a polysemic term, Regionalism refers both to practices of region formation and to a subfield of IR.[27] Since the early 1990s, globalization of trade and investment flows has been accompanied by increased efforts at regional economic governance. As a practice, Regionalism now constitutes an element of an increasingly complex system of governance operating at a variety of levels in which questions about public goods, welfare, economic organization and political participation are addressed. Yet, as a practice, Regionalism is generally associated with regional organizations (ROs). Indeed, there has long been a global upsurge in various forms of regionalist projects in different parts of the world. By now, almost every country in the world has formal relations with at least one form of regional organization.[28] In nearly every part of the world, regional organizations have been created or have acquired fresh impetus. Many regionalist projects have been revitalized or expanded, including, among others, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the Southern Common Market (Mercosur). ASEAN survived the Asian crisis and became the center of East Asian regional cooperation, while other regional organizations were established in Eurasia (the Eurasian Economic Union, EEU) and South America (the Union of South American Nations, UNASUR). Most significantly, with the initiation of African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Africa and the African Union are on track to provide for continental free trade and regional integration.[29] In terms of contemporary regionalism practices, we should pay greater attention to Africa, Asia, Eurasia and Latin America rather than Europe. Furthermore, governments not only formally engage in some kind of regionalism, but actively participate in regionalist processes with the engagement of a multitude of corporate and civil society players through the phenomenon we call regionalization.[30]

Economy and trade are important drivers of regionalism.[31] In this sense, Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) are one of the most important aspects of regionalism practices today. As modern RTAs have become more and more complex in their scope and content, they have grown significantly in recent years and are now a key trade policy feature for almost every country. Over time, the history of RTAs also indicates that negotiations are increasingly cross-regional and exist between developed and developing countries, while today a large proportion of agreements also take place between developing countries. Although RTAs were originally driven mainly by the European Union and the United States, today's RTAs, especially RTA negotiations, are concentrated in Asia[32]

In addition to these various aspects and insights in practice, Regionalism as a theory represents the body of ideas, values and policies that aim to create a region or, in another sense, a type of unique and geographically-limited world order. The phenomenal growth in numbers of ROs and the range of their activities over the last century has correspondingly generated much interest in the study of Regionalism itself. However, its meaning and content have evolved substantially since its inception in the early 1950s. Over the years, Regionalism has increasingly shifted away from Europe (both as a place of academic development and as an analytical case study) to address non-European and, more generally, non-Western and postcolonial domains, questioning theoretical and epistemological eurocentric concepts in IR. In this sense, Regionalism today is defined using post-neo-liberal,[33] post-hegemonic,[34] porous-regionalism[35] terminologies.

We often contextualize and historicize Regionalism in various clusters. Early Regionalism, new Regionalism, and comparative Regionalism are the common names for these clusters.[36] Yet, today we have arrived at inter-trans-cross Regionalism as increasing contacts between different regions have grown into a significant phenomenon in recent decades.[37] This is a very significant development as granting regions agency in IR along with nation-states requires whole new sets of thinking and theories. Many of these new sets of ideas, perspectives and theories derive from non-Western contexts or an amalgam of Western and non-Western interactions.

However, inter-trans-cross Regionalism is still a poorly understood phenomenon and the literature on these new forms is scant,[38] with much of it concerning intra-regional dynamics and relations while the inter-trans-cross regional relations remain neglected. Further study on these concepts and re-thinking regions themselves and Regionalism are required in light of contemporary global transformations.[39]

3. Regionalism and Globalizing IR

When it comes to the task of globalizing IR, Regionalism studies offer a very distinct example. Even though deep-rooted Eurocentrism and a certain degree of exclusionary practices still guide substantial research clusters in this sub-field, it is more dynamic than ever and reflects a position that is more conceptually aware of non-Western thinking and practices.

Today, there is a broad consensus that the Global South presents distinct social, political, economic and security challenges that necessitate a set of regional knowledge different from Western typologies, conceptions and theories. In general, non-Western Regionalism is full of concerns about the ability to preserve boundaries, while regional systems tend to have low levels of formality and light bureaucracy, ultimately resulting in non-binding results in certain cases.[40] Moreover, structural and extra-regional influences are more to the fore and are conceptualized by non-European Regionalism studies.[41] Furthermore, Regionalism is not so much about liberalizing trade and fostering democracy in many areas of the world today, nor is it geared strictly toward security goals when it comes to non-Western cases.[42] Recognizing that Western and, in particular, European concepts and theories have been of little use in making sense of these predicaments, heterogeneity in knowledge production along epistemological, theoretical and methodological lines is an indispensable development. Indeed, researchers of the new Regionalism have firmly rejected the 'Eurocentrism' of the classic theories of integration since the 1990s and created better theoretical approaches to explore regionalism in regions other than Europe.[43]

However, as underlined in the introduction, it is no longer enough to state that IR is suffering from Eurocentrism. The second-order challenge for those who wish to drive IR forward is to show that ideas and theories originating from non-Western contexts can be extended beyond their particular national or regional contexts.[44] That’s why, the argument here is that this type of practice and theory of Regionalism has important ramifications beyond the respective geography of each. To map out emerging non-Western contributions to the Regionalism literature, we have conducted a bibliometric analysis.

4. Bibliometric Analysis

4.1. Material and method

Bibliometric analysis is a statistical classification and examination of the contents of publications in a journal, book or other types of field directory. It was first named ‘Statistical Bibliography’ by E. Wyndham Hulme in 1923[45] and later brought to the literature as ‘bibliometric’ by Pritchard and Gross with the idea that the term would be more understandable.[46] Bibliometric studies allow quantitative evaluation of literature through a number of indicators and can be used to assess the incidence of different fields of study. By considering the citations mentioned in any of a series of articles, bibliometrics may also be used to evaluate the importance of a given article to a specific area.[47] In any case, most of these quantitative field inputs are based upon existing publications in indexed science databases. It is possible to analyze the development in any scientific literature through main parameters such as most frequently used keywords, most cited publications, inter-author relations, country of origin, etc.[48]

This article conducts an explanatory statistical analysis using bibliometric data collected from the WoS database, which is among the most widely used tools for generating bibliometric data in the Arts and Humanities and Social Sciences. WoS initially consists of three ISI citations indeces (Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Scientific Citation Index, and Social Sciences Citation Index), and its coverage extends back to 1956 for the Social Sciences Citation Index and 1975 for the Arts & Humanities Citation Index.[49] To identify all potential matches of the relevant works in the database, we used a precise match search approach that uses a single search term and locates all exact matches in the recorded field. Our search term was ‘Regionalism’ since it hints at all the relevant works in the database.

In our study, 883 documents on Regionalism were examined in the WoS database. These were all published from 1980 through 2021. When the non-field studies in the category of area studies were cleared from the data set, 866 documents were examined. There remained 852 documents when unrelated or missing contents were removed. Of these, 385 were articles and 27, books. There were 802 authors, with 1.08 documents per author. The annual average number of publications was 10.8.

4.2. Result and discussion

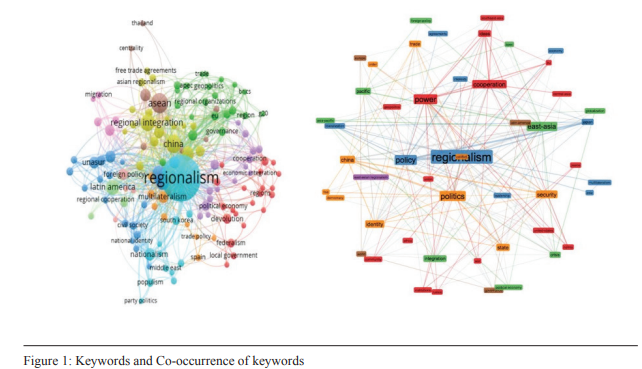

With any keywords, the search results from WoS consist of a list of articles ordered by keyword significance. To reveal patterns and developments in the literature on Regionalism, a co-word analysis was used, which can be seen in Figure 1. This analysis consisted of all of the articles and their respective keywords such as regional integrations, regional order, regional organizations, etc. The co-word analysis shows that ‘Regionalism’ as a keyword is the most representative keyword among others when it comes to overall Regionalism studies.

Conventional bibliometric approaches such as author and journal co-citation analyses lead to insightful findings. For example, co-word analysis, which counts and analyzes the co-occurrence of keywords in publications on a given subject, can provide an immediate picture of the actual content of the overall literature. From this point, it can be argued that the content of the literature on Regionalism has now broadened to reflect the Global South's social, political, economic and security predicaments.

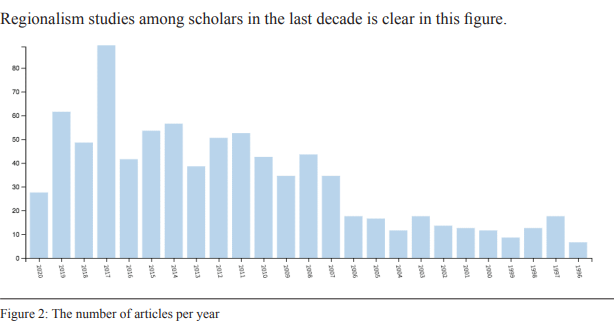

The number of documents per year related to the given keyword ‘Regionalism’ is listed in Figure 2. There were 866 published articles indexed by the WoS between 1980 and 2020, and after data clearance, 852 entries were included in our analysis. The growing interest in Regionalism studies among scholars in the last decade is clear in this figure.

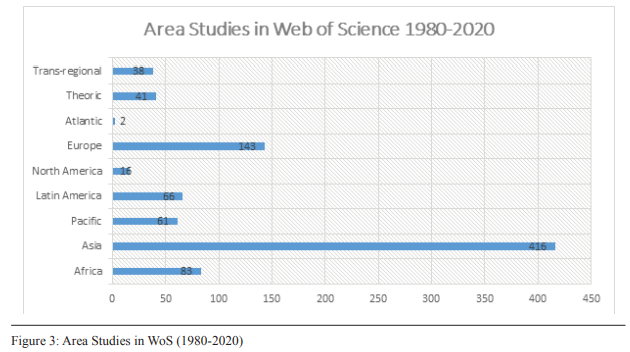

One critical purpose of this research is to classify which regions these papers are studying. This information is reflected in Figure 3 above. Concerning the study of Regionalism, the bibliometric data distinguishes the following applications: Trans-regional studies (38), Regionalism theories (41), US-European dynamics (2), EU-related research (143), North American Regionalism (16), Latin American Regionalism (66), Pacific (61) and Asian Regionalism (416), and finally, African Regionalism (83). According to the compiled data, only 145 (Europe+Atlantic) articles were in the European context. The rest deal with the non-European context. Almost half of the entire 883 published articles indexed by the WoS between 1980 and 2020 are on Asia and Asia-related topics. Given the dominance of Latin American, African and Asian related research in the literature, we can verify our earlier contention that Regionalism studies are no longer dominated by the EU per se, but are now mostly non-European/non-Western in context, and particularly Asian.

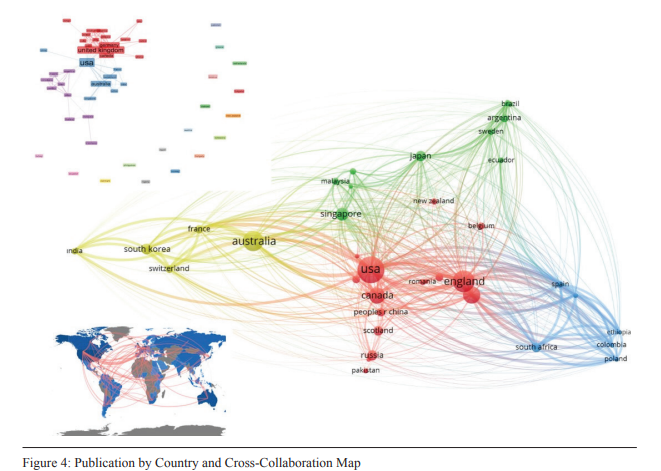

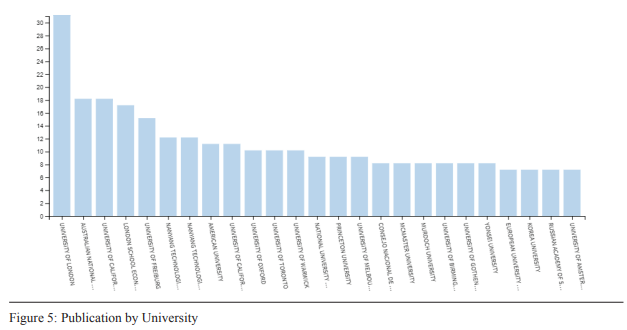

Figures 4 and 5 below provide the number of articles on Regionalism in terms of country of origin and by institution. From the figures, we see that most studies still originate from Western countries and institutions. Similarly to the dominant trend in IR literature, many of these publications originate in the US. Yet, a closer look at current cross-national collaborative publications on Regionalism indicates that despite asymmetries between the amount of knowledge production between Western (American and British) and Non-Western countries, several non-Western institutions have come more to the fore over the years. In particular, the extent of cross-national collaboration indicates that Regionalism has become a global literature that flows extensively beyond borders.

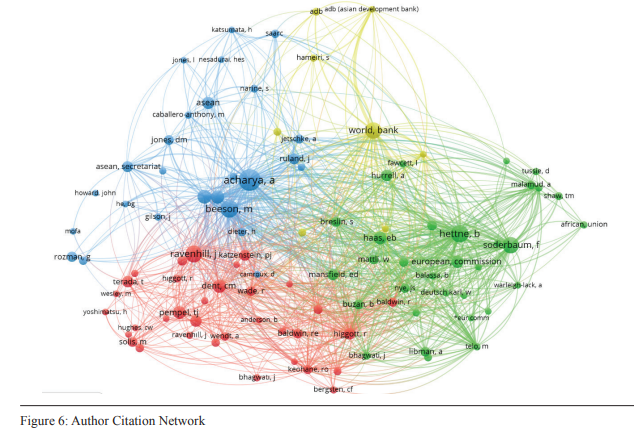

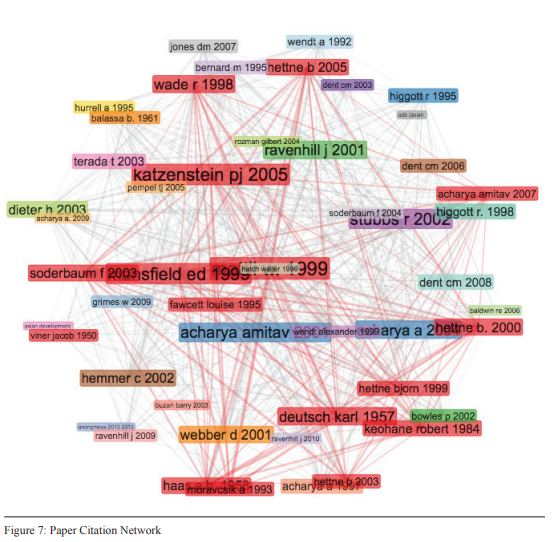

Co-citation analyses are a good way of analyzing the discipline's intellectual structure. We conducted an author- and paper-based approach in building the co-citation networks. When it comes to authors, Western domination can be seen. Figure 6 shows publication by authors and Figure 7 illustrates the impact of specific papers within a citation network. Both figures are informative about the contribution to the literature from Western and non-Western areas. While some of these authors are originally from the South, they study and work in Western countries, and therefore they are listed as Western scholars in the publication by country and other collaborative study maps.

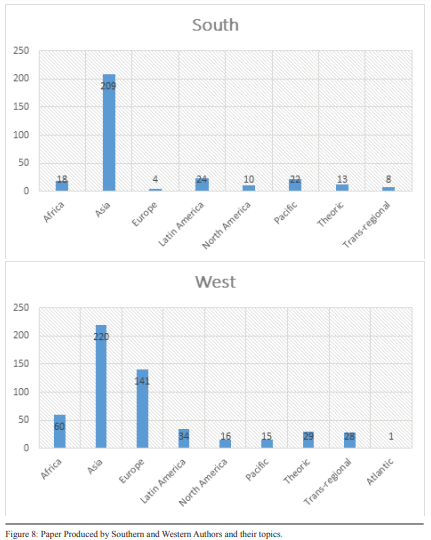

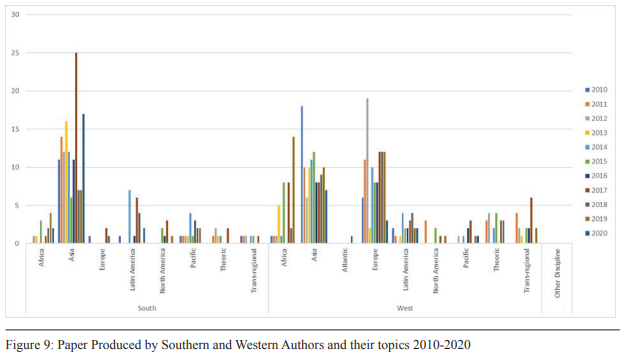

In order to find out the exact picture of the South’s contribution, we have organized the data to visualize the Western and Southern contribution to Regionalism literature as separate entries. Figures 8 and 9 are two important figures from which we can attribute specific contributions coming from the South. In these figures, the left-hand side of Figure 8 shows how many papers were produced by Southern names independent of where they study and work. The right-hand side of Figure 8 does the same for Western names. These two figures also reveal what topics are studied by these Regionalism scholars. It is clear from these figures that both Southern and Western scholars overwhelmingly work on Asia. Figure 9 illustrates the increasing interest in Asian studies from both Southern and Western scholars in the last decade. African and Latin American subjects are common for Western scholars along with more dominant European Regionalism. This is one indicator that Regionalism is a field where Global IR trajectories are relatively well-met not just in terms of growing attempts to challenge Western centrism and to give more room and voice to the Global South, but also in terms of developing concepts and approaches from the latter’s unique context and applying them in other places.

5. Conclusion

IR is a hierarchical discipline, and diversity along theoretical, topical and national/regional dividing lines is not always apparent. The simplest way to detect diversity is to look for contributions from non-Western scholarship. However, it would be naïve to try and understand the extent of diversity in IR scholarship by looking at how many knowledge claims exist. Contrary to general expectations, research trends in IR communities (both Western and non-Western) are quite similar in terms of epistemology and methodology.[50]

Global IR scholars are encouraging greater IR inclusiveness and diversity by opening up spaces for a wider spectrum of histories, perspectives, and theoretical insights, particularly those beyond the West. The primary driver for this paper is to illustrate that the study of Regionalism is in a prime position to promote the ‘Global IR vision’ since it genuinely represents such a field that is open to new thoughts, theories and approaches from non-Western societies in particular.

We conducted a bibliometric analysis as a proxy to chart the diverse and complex intellectual structure of the literature on Regionalism with contributions from various areas of the world. The first observation of the paper is that Regionalism studies are more diverse than ever, evolving, self-innovating, and becoming more conceptually conscious of non-Western theory and practice, even though some study clusters are still driven by deep-rooted Eurocentrism along with some degree of exclusionary practices. Secondly, the specific bibliometric analyses, such as the co-word approach, show that Regionalism literature is now conscious of the problems related to the social, political, economic and security predicament of the Global South. That trend is also verified by the number of contributions from Southern scholars on Regionalism. Correspondingly, the phenomenal rise in the total number of submissions from non-Western academics and publications in the last decade has created enormous interest in problems of the South in Regionalism studies.[51] Therefore, we see that Regionalism studies are now overwhelmingly in non-European/non-Western contexts, particularly in Asia, rather than in European contexts.

Finally, the results extracted from the data also indicate that the curiosity of both Southern and Western academics in non-Western regions has risen over the last decade. Asian, African and Latin American issues have become popular among Western academics as well. This is one of the metrics that show us that Southern issues and theories are not just studied by Southern scholars but also by their Western counterparts.

Acharya, Amitav. “Comparative Regionalism: A Field Whose Time Has Come?” The International Spectator 47, no. 1 (2012): 3–15.

———. “The Emerging Regional Architecture of World Politics.” World Politics 59, no. 4 (2007): 629–52.

———. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

———. “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organization 58, no. 2 (2004): 239–75.

———. “An IR for the Global South or a Global IR?” E-International Relations (blog), October 21, 2015. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://www.e-ir.info/2015/10/21/an-ir-for-the-global-south-or-a-global-ir/.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. “Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? Ten Years On.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17, no. 3 (2017): 341–70.

Acharya, Amitav, Melisa Deciancio, and Diana Tussie, eds. Latin America in Global International Relations. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Al, Arzu, and Hakan Mehmetcik. “Economic Regionalization and Black Sea in a Comparative Perspective.” Siyasal Bilimler Dergisi 5, no. special issue (2017): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.14782/sbd.201.54.

Alejandro, Audrey. “Eurocentrism, Ethnocentrism, and Misery of Position: International Relations in Europe–A Problematic Oversight.” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 4 (2017): 5–20.

Andrews, Nathan. “International Relations (IR) Pedagogy, Dialogue and Diversity: Taking the IR Course Syllabus Seriously.” All Azimuth 9, no. 2 (2020): 267–81.

Aris, Stephen. “Fragmenting and Connecting? The Diverging Geometries and Extents of IR’s Interdisciplinary Knowledge-Relations.” European Journal of International Relations (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120922605.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing. Routledge, 2018.

Baert, Francis, Tiziana Scaramagli, and Fredrik Söderbaum, eds. Intersecting Interregionalism: Regions, Global Governance and the EU. United Nations University Series on Regionalism, volume 7. Dordrecht; New York: Springer, 2014.

Baldwin, Richard. “21st Century Regionalism: Filling the Gap between 21st Century Trade and 20th Century Trade Rules.” WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-08, no. 56, 2011.

Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “Identity Politics, Core State Powers, and Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies n/a, no. n/a. Accessed November 10, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12982.

———. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Breslin, Shaun, ed. New Regionalisms in the Global Political Economy: Theories and Cases. 1 edition. London ; New York: Routledge, 2002.

Breslin, Shaun, and Richard Higgott. “Studying Regions: Learning from the Old, Constructing the New.” New Political Economy 5, no. 3 (2000): 333–52.

Briceno-Ruiz, Jose, and Isidro Morales. Post-Hegemonic Regionalism in the Americas: Toward a Pacific–Atlantic Divide? Taylor & Francis, 2017.

Buranelli, Filippo Costa, and Aliya Tskhay. “Regionalism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, August 28, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.517.

Buzan, Barry, and Richard Little. “Why International Relations Has Failed as an Intellectual Project and What to Do About It.” Millennium 30, no. 1 (2001): 19–39.

Cusack, Asa K. “Venezuela, ALBA, and the Limits of Postneoliberal Regionalism.” In Venezuela, ALBA, and the Limits of Postneoliberal Regionalism in Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Asa K. Cusack, 191–212. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2019.

———. Venezuela, ALBA, and the Limits of Postneoliberal Regionalism in Latin America and the Caribbean. Springer, 2018.

Eun, Yong-Soo. “Opening up the Debate over 'Non-Western' International Relations.” Politics 39, no. 1 (2019): 4–17.

Fawcett, Louise. “The History and Concept of Regionalism.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 2012. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2193746.

Futák-Campbell, Beatrix. Globalizing Regionalism and International Relations. Bristol University Press, 2021.

Gardini, Gian Luca, and Andrés Malamud. “Debunking Interregionalism: Concepts, Types and Critique–With a Pan-Atlantic Focus.” In Interregionalism across the Atlantic Space, edited by Frank Mattheis and Andréas Litsegård, 15–31. Springer, 2018.

Gelardi, M. “Moving Global IR Forward—A Road Map.” International Studies Review 22, no. 4 (2020): 830–52.

Hänggi, Heiner. “Interregionalism: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives.” Paper prepared for the Workshop “Dollars, Democracy and Trade: External Influence on Economic Integration in the Americas,” Los Angeles, CA, May 18, 2000.

He, Baogang, and Takashi Inoguchi. “Introduction to Ideas of Asian Regionalism.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 12, no. 2 (2011): 165–77.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus (1977): 41–60.

Hulme, Edward Wyndham. Statistical Bibliography in Relation to the Growth of Modern Civilization. London: Butler&Tanner, 1923.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus. “Must International Studies Be a Science?” Millennium 43, no. 3 (2015): 942–65.

———. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. 1st ed. London; New York: Routledge, 2011.

Kaplan, Morton A. “Is International Relations a Discipline?” The Journal of Politics 23, no. 3 (1961): 462–76.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and Takashi Shiraishi, eds. Beyond Japan: The Dynamics of East Asian Regionalism. Cornell University Press, 2006.

Kilicoglu, Ozge, and Hakan Mehmetcik. “Science Mapping for Radiation Shielding Research.” Radiation Physics and Chemistry 189 (2021). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109721.

Lawani, Stephen Majebi. “Bibliometrics: Its Theoretical Foundations, Methods and Applications.” Libri 31 (1981): 294.

Leslie, Helen, and Kirsty Wild. “Post-Hegemonic Regionalism in Oceania: Examining the Development Potential of the New Framework for Pacific Regionalism.” The Pacific Review 0, no. 0 (2017): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1305984.

MacKay, Joseph, and Christopher David LaRoche. “The Conduct of History in International Relations: Rethinking Philosophy of History in IR Theory.” International Theory 9, no. 2 (2017): 203–36.

Maghroori, Ray, and Bennett Ramberg. Globalism versus Realism: International Relations’ Third Debate. Westview Press, 1982.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Etel Solingen. “Regionalism.” Annual Review of Political Science 13, no. 1 (May 2010): 145–63.

Maxwell, Alexander. “Regionalism and the Critique of 'Eurocentrism': A Europeanist’s Perspective on Teaching Modern World History.” World History Connected 9, no. 3 (2012): 49.

Mehmetcik, Hakan. “Bölgeselcilik çalışmalarında bölgeler üstü ve bölgeler arası ilişkiler: Avrupa Birliği ve Afrika Birliği ilişkileri örneği.” International Journal of Political Science and Urban Studies 7 (2019): 72–84.

Mehmetçik, Hakan. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler çalışmaları ve 'neden Batılı olmayan bir uluslararası ilişkiler teorisi yok?' sorusuna cevap aramak.” Journal of Faculty of Political Science 50 (2014): 243–58.

Meho, Lokman I., and Kiduk Yang. “A New Era in Citation and Bibliometric Analyses: Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar.” ArXiv:Cs/0612132, December 23, 2006. http://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0612132.

Pritchard, Alan, and Ole V. Groos. “Documentation Notes.” Journal of Documentation 25, no. 4 (1969): 344–49.

Riggirozzi, Pia, and Diana Tussie, ed. “Rethinking Our Region in a Post-Hegemonic Moment.” In Post-Hegemonic Regionalism in the Americas. Towards a Pacific vs. Atlantic Divide, 16–31. Routledge, 2017.

Sever, Aysegul, and Hakan Mehmetcik. “Regional Organizations and Legitimacy.” In The Crises of Legitimacy in Global Governance, edited by Gonca Oguz Gok and Hakan Mehmetcik. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

Söderbaum, Fredrik. “Early, Old, New and Comparative Regionalism: The Scholarly Development of the Field.” KFG Working Paper Series No. 64, Freie Universität Berlin, 2015. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2687942.

Stuenkel, Oliver. Post-Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking Global Order. 1st edition. Malden, MA: Polity, 2016.

Tickner, Arlene B., ed. International Relations Scholarship Around the World. 1st edition. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2009.

Voskressenski, Alexei D. “Introduction.” In Non-Western Theories of International Relations: Conceptualizing World Regional Studies, edited by Alexei D. Voskressenski, 1–15. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

Wæver, Ole, and Arlene Tickner. “Geocultural Epistemologies.” In Vol. 1, International Relations Scholarship around the World: Worlding Beyond the West, 1–31. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2009.

Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Wiebke, Nicholas J. Bell, Mariana Navarrete Morales, and Michael J. Tierney. “The IR of the Beholder: Examining Global IR Using the 2014 TRIP Survey.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 16–32.

Wight, Martin. “Why Is There No International Theory?” International Relations 2, no. 1 (1960): 35–48.