James M. Scott

Texas Christian University

Charles M. Rowling

University of Nebraska

Timothy M. Jones

Bellevue College

Democracy promotion emerged as a US foreign policy priority during the late 20th century, especially after the Cold War. Scarce resources, however, require policymakers to make difficult choices about which countries should receive democracy aid and which ones should not. Previous studies indicate that a variety of factors shape democracy aid allocations, including donor strategic interests and democratic openings within potential recipient states. Research has also shown that media coverage plays a significant role in these decisions. We model the conditional effects of media attention and regime shifts on US democracy aid decisions, controlling for other recipient and donor variables. We argue that these factors are contingent on the salience, in terms of broad interest profiles, of a particular country for policymakers. The donor’s overall level of interest in a potential recipient systematically shapes the effects of media attention on democracy assistance. Broadly speaking, low-interest conditions elevate the agenda-setting impact of media attention and regime conditions/shifts while high-interest conditions reduce that effect. To assess these contingent relationships, we examine US democracy aid from 1975-2010. Our results support our argument and present a more nuanced explanation of the relationship between the media’s agenda-setting role, recipient characteristics and donor interests.

1. Introduction

For years, the United States has been allocating targeted packages of democracy assistance to foreign governments, political parties, and non-governmental organizations. However, such resources are scarce, forcing policymakers to make difficult choices about recipients. Previous studies by numerous scholars indicate that determinants such as strategic interests, ideational considerations, and the likelihood of success of democratization shape these decisions. Research has also shown that media coverage affects these decisions by increasing the visibility of the dynamics within potential recipient countries.

In this study, while controlling for other recipient and donor variables, we advance the novel argument that policymakers’ broad interest profiles of a particular country shape the conditional effects of media attention and regime shifts in US democracy aid decisions. As we explain, the donor’s overall interest in a potential recipient – defined as level of engagement and cooperation – systematically shapes the effects of media attention on democracy assistance. Broadly speaking, low-interest conditions elevate the impact of media attention and regime conditions/shifts while high-interest conditions reduce that effect. Examining US democracy aid from 1975-2010, we find support for our nuanced explanation of the relationship between donor interests, the media’s agenda-setting role, and recipient characteristics.

2. Foreign Aid, Democracy Aid and Allocation Decisions

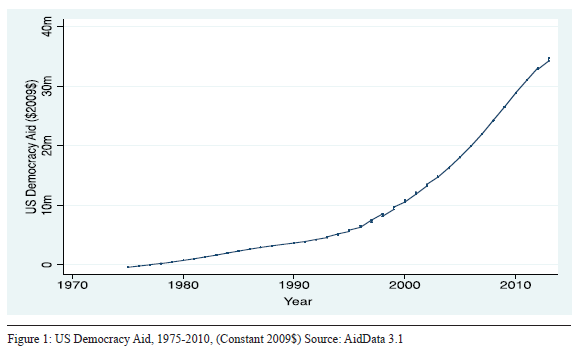

A component of foreign aid, democracy assistance targets civil society organizations and political institutions to promote democratization. From 1975–2010, US democracy assistance grew from negligible amounts to $3-4 billion annually (about 14% of foreign aid), on par with aid priorities such as health, emergency response, and agriculture. The US provides roughly a third of this aid directly to NGOs.

Most empirical research on democracy aid focuses on its outcomes or the determinants of its allocation. On its effects, numerous studies conclude that democracy aid has positive consequences for democratization.[1] On the allocation side, studies concerned with democracy aid (and foreign aid more generally) find varying influence from recipient regime characteristics; human rights behavior; recipient development and humanitarian needs; economic, political and security interests of donors; considerations of feasibility; colonial legacies; situational factors such as economic crises, conflict and political changes; and bargaining between donors and recipients.[2] Significantly, in both democracy and foreign aid, donor interests are central: because scholarship has found positive relationships between aid and alliances/military relationships, foreign policy affinity/ideological alignment, and other interests, it is clear that “donors expect political benefits from their aid.”[3]

Studies of democracy aid, thus, build on the foreign aid literature to emphasize three central findings, which serve as the foundation of our argument. First, studies have shown that political, economic, and strategic interests are significant factors in determining democracy aid allocations, though their effects are often different on foreign aid.[4] Second, along with other recipient characteristics, recipient democratic conditions and trajectories also shape democracy aid decisions as policymakers look for situations in which democratization is underway, most promising, or likely.[5] Third, a country’s visibility in the news affects the extent to which it is prioritized. In general, the more visible a country is in news coverage, the more foreign aid – including democracy assistance – it tends to receive.[6] However, we argue that these pieces do not operate independently of one another. We, therefore, construct a novel argument that better captures the nuances, interactions, and contingencies of these pieces and offers an improved and more comprehensive explanation of US democracy aid allocations.

3. Targeting Democracy Aid: Democratic Change, Media Attention, and Donor Interests

To begin, we build on research showing that democratic conditions and trajectories in potential recipient states significantly shape US democracy assistance decisions. Specifically, regime conditions and regime shifts serve as the basis for assessing democratic demand and feasibility. Because donors are concerned about the efficacy of democracy aid, they look for evidence of demand and feasibility in regime conditions exhibiting democratic features. More promising recipients garner more assistance. In this context, regime shifts – democratic openings demonstrated by shifts toward democracy – signal opportunities and increase donor confidence in the potential efficacy of democracy assistance. Thus, regimes that possess democratic features and are experiencing a shift toward democracy tend to receive more democracy assistance than those that do not.[7]

Media attention also influences which countries receive foreign aid, and democracy aid is no exception. As Linsky has argued: “The press has a huge and identifiable impact... Officials believe that the media do a lot to set the policy agenda and to influence how an issue is understood by policymakers.”[8] The news media are central to the creation, reinforcement and promotion of ways the public and policymakers see the world, and studies have shown that country salience in the media affects the prioritization of that country among policymakers.[9] High levels of media attention signal to donors that a potential recipient is important and, therefore, tend to correlate with an increase in foreign aid.[10] For example, media attention is a key factor in donors’ decisions to impose foreign aid sanctions on repressive regimes and can increase public attentiveness to some situations, contribute to accountability, and generate electoral concerns for policymakers in democratic governments.[11] Thus, those countries that are highly visible in news coverage tend to receive more attention from policymakers and, in combination with other factors, are more likely to receive democracy aid.[12]

Moreover, the impact of media attention on democracy aid allocations becomes even more consequential when it interacts with regime shifts, especially those toward democracy.[13] Specifically, the media shine a spotlight on those countries undergoing shifts toward democracy, cueing policymakers to allocate democracy assistance. Visibility in news coverage validates democratic openings and increases confidence in the feasibility of democracy assistance. Conversely, without media attention, such shifts are potentially less salient and more uncertain, resulting in less democratic assistance. In part, a lack of visibility reinforces the wariness of US policymakers about the uncertainty surrounding such regime changes.

Donor interests, broadly conceived, are also important factors in democracy aid decisions. We argue, however, that they systematically condition the effects of other determinants and their interaction. Consistent with other scholarship, we regard donor interests as the broad material benefits – specifically, those related to engaged and cooperative security relationships, political alignment and support, and economic interactions such as trade – associated with aid allocations.[14] As noted, research indicates that greater donor interests in a potential recipient tends to result in more foreign aid. Such aid tends to enhance and sustain the relationship between the donor and the recipient.

On democracy aid, however, we argue that these dynamics function differently. Democratization entails regime change, or at least the altering of institutions and political processes. Thus, while donor interests remain important to democracy aid decisions, their impact on these decisions is likely to be the opposite of how they tend to affect foreign aid decisions. Indeed, US policymakers are likely to be more inclined to promote democracy in places perceived to be less important for donor interests simply because there is less risk that such action could potentially undermine US relationships and interests there. Put another way, in democracy aid decisions, US policymakers are likely to be wary of destabilizing regimes with whom the United States already has an established, beneficial, and cooperative relationship.[15] Moreover, when media attention is absent, regime shifts tend to reduce US democracy aid.[16] We extrapolate from and extend these findings to offer our first hypothesis:

H1: Low-interest potential recipients are more likely to receive democracy assistance than high-interest potential recipients.

Although studies have found that donor interests play a role alongside media attention, regime conditions/shifts, their interaction, and other factors, our novel argument is that such interests first condition the effects of these dynamics. Specifically, we contend that media attention, regime conditions/shifts, the interaction of these variables, and other factors operate differently depending on donors’ specific interests. While previous studies offer valuable insight into US democracy aid allocations, the picture remains incomplete because the factors shaping these decisions, especially the role and influence of democratic openings, media visibility and their interactions, are contingent on donor interest profiles. Thus, the way in which US democracy aid allocators respond to increased media attention and regime shifts in a potential recipient country depends on broad levels of US interest in that country.

Specifically, we argue that when the broad profile of US interests is high – when engagement and cooperative/beneficial relationships are more extensive – policymakers pay more attention to and have more knowledge about potential aid recipients. In such high-interest profiles, policymakers will depend much less on media attention when making democracy aid decisions. There is also likely to be preference for preserving a stable relationship with high-interest potential recipients. Increased media attention and regime shifts within high-interest potential recipients are, therefore, unlikely to shape donor calculations or cause a substantial shift in the prioritization of these potential recipients. In effect, the agenda-setting power of the press diminishes in the context of established relationships and high interest profiles.

By contrast, when the broad interest profile of potential recipients is low – when engagement and cooperative/beneficial relationships are less extensive – the potential recipients in question are less salient to US policymakers. Increased media attention and regime shifts in low-interest potential recipients should, therefore, play more consequential roles in bringing policymakers’ attention to bear on those situations. The low-interest nature of these situations involves less saliency, lower awareness, and fewer sunk costs and existing commitments. The opportunity afforded by regime shifts is thus more likely to attract attention when the media helps to bring visibility to the situation. Where the media does not bring attention to bear, the low-interest profile of the situation is likely to reduce aid commitments, given the uncertainty and perceived risk. While specific kinds of US interests (e.g., strategic, political, economic) are likely to remain important – albeit in different ways – for aid decisions in either profile, the broad differences in interest profile set the context for critical variance in the impact of media attention and regime shifts. This leads to our central hypothesis, which reflects this three-way relationship:

H2: Potential recipients of low (high) interest experiencing regime shifts toward democracy and greater media attention will receive more (less) democracy aid than other potential recipients.

4. Data and Methods

To test our argument, we examine US democracy aid to the developing world from 1975-2010, using AidData 3.1 project-level aid.[17] We thus examine country-year data for the 36-year period of our analysis. From AidData 3.1, we extract US democracy aid and aggregate it to annual commitments to each country. Using AidData project codes, we disaggregate aid into democracy assistance (purpose codes 15000-15199) and other development aid (all other purpose codes). Using annual Penn World Tables population data, we then compute annual per capita democracy aid for each country. The average annual per capita democracy aid for the period of our analysis is $574.5 (s.d. 4187.3), ranging from 0 to a high of $164,198.8.

Four independent variables form the foundation of our argument: regime conditions, regime shifts, media attention, and donor interest profiles. In all our models, these independent variables are lagged one year behind our democracy aid measures to ensure that they precede the aid allocations.[18]

Media Attention. Our measure of country visibility derives from coverage of foreign nations by major US news outlets. We select the New York Times and CBS Evening News to represent print and television news. The New York Times is recognized as the “newspaper of record” within the United States and CBS Evening News has the largest viewing audience among television news networks during our study’s time frame.[19] We collect New York Times content from abstracts in the historical New York Times Index and CBS Evening News content from the Vanderbilt Television News Index. Scholars routinely use print and television news abstracts as proxies to analyze news content: attention devoted to a topic in an abstract is roughly equivalent to attention given to that same topic in a full story.[20] We use computer-aided content analysis to count country mentions, focusing on the number of news stories about a foreign nation, rather than the number of mentions for a foreign nation within each news story. Thus, each country is given a 0 or 1 based on whether it is mentioned within each news story. We relied on the names of each country as our search terms, taking into account usage and context (thus avoiding conflating “turkey” and “Turkey,” or “Jordan” and “Michael Jordan” for example) and multiple versions of some country names. Average annual mentions are 56.1 for the NYT (s.d. 120.2), ranging from 0 to 2723.5, and 10.5 for CBS (s.d. 35.2), ranging from 0 to 655. In all our models, our measures for media mentions are lagged one year behind our democracy aid measures to ensure that they precede the aid allocations.

Regime Conditions and Regime Shifts. We measure regime conditions and regime shifts with the Polity2 variable, a composite score (-10, least democratic, to 10, most democratic) in Polity IV data (Marshall and Jaggers 2012; Munck and Verkuilen 2002).[21] Following Plumper and Neumayer, we substitute Freedom House scores (2-14, transposed to set lower values as less free, adjusted to the Polity2 scale, and rounded to the lower value) for the missing variable for interruptions (-66) in Polity2, while keeping the interpolated scores in Polity2 for transitions (-88) to improve face validity.[22] This approach avoids artificial changes to the Polity2 score derived from substituting 0 for the interregnum. Because we recognize that different measures of democracy have varying strengths and limits, we also conducted our tests substituting Freedom House scores for the Polity scores. Our results were fully consistent, and we do not report those tests here.[23]

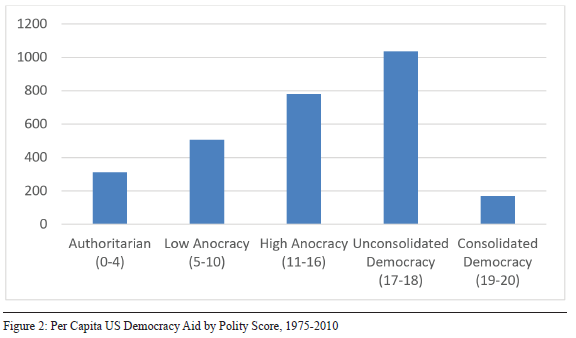

Our adjusted Polity2 score is the basis for our measure of regime conditions. We reset the adjusted scores to 0-20 (0=the most autocratic conditions). Consolidated democracies receive little to no democracy assistance (see Figure 2), chiefly because of a “graduation” effect: donors reduce or eliminate democracy aid to consolidated democracies, potentially replacing the aid with other forms of support and assistance. To avoid biasing our results by including situations in which democracy aid reductions are driven by this graduation effect, we drop consolidated democracies (scores of 19-20) from the data.[24] Regime conditions average 7.8 (s.d. 6.2). In all our models, we lag our measure for regime conditions one year behind our democracy aid measures to ensure that they precede the aid allocations.

We measure regime shifts by subtracting the adjusted score at time t-2 from time t to calculate shift over the two-year period. Our results range from a 15-point shift toward autocracy to a 16-point shift toward democracy; our data thus measure both shifts toward and away from democracy. Regime shifts average 0.4 (s.d. 2.7), ranging from -15 to 16 points of change on our adjusted polity measure (0-18). In all our models, the measure of regime shift is lagged one year behind the dependent variable. Thus, in effect, for aid allocations in year t, the regime shift variable measures the change in adjusted score from t-3 to t-1. For the key variable in our study, we interact our measures of regime shifts and media attention (MEDIA ATTENTION*REGIME SHIFTS) to gauge the conditional effects of media attention at different levels of regime shifts. In all our models, we lag this interaction term one year behind the dependent variable.

Donor (US) interest profiles. We argue that the conditional effects of media attention and regime shifts are contingent on donor interest profiles. We begin with individual measures for economic, political, and security interests. For US economic interests, we include US trade as the sum of imports and exports (in current dollars) between the United States and a potential recipient.[25] For US political interests, we use affinity scores (s-score) from Strezhnev and Voeten, a measure commonly used for similar interests/political affinity.[26] These affinity scores are based on UN General Assembly voting data in which higher scores indicate similar voting (affinity) between a potential recipient and the United States. We also operationalized political interests with idealpoint measures.[27] Our results were consistent, and we do not report those tests here.[28] For US security interests, we code a dichotomous measure for the presence of an alliance between a potential recipient and the United States for each year using Correlates of War Alliance data.[29] Because this is a simple, though widely used, measure, we also used Bell et al’s security salience measure, substituting it for the dichotomous alliance measure. Our results were fully consistent, and we do not report those tests here.[30]

From these data, we compute an overall measure for the broad interest profile of the United States and a potential recipient, differentiating between low and high interests in each interest variable. For economic (trade) and political (s-score) interests/affinity, we identify the mean value of each measure in our dataset and designate potential recipients above the mean as “high-interest” and those below as “low-interest.” For security (alliance) interests/affinity, we designate potential recipients with an alliance with the United States as “high-interest” and those without as “low-interest.” We argue that high interest profiles require positive connections across multiple dimensions, so we compute an ordinal variable in which 0 = low interest in all three areas; 1 = high interest in 1 of 3 areas; 2 = high interest in 2 of 3 areas; 3 = high interest in 3 of 3 areas. From this ordinal measure, we recode for the overall US interests profile with a dichotomous variable where High Interests (1) = values 2 and 3 and Low Interests (0) = values 0 and 1 on the ordinal scale. In the main tests of our argument, we use this measure to distinguish between broad interest profiles, but we also include the individual economic, political, and security interest variables to capture and control for variation in and effects of these more specific interests on democracy assistance. In all our models, we lag our measures for high and low interest profiles behind democracy aid allocations by one year.

Control Variables. We include several control variables. In the models using subsamples, we include trade, political interests, and alliances, as identified in the preceding discussion. Also, in all models, we include a measure of “other aid” to control for general US aid commitments to a recipient. We subtract democracy aid from total aid and calculate its logarithm in constant 2009 dollars. Finally, we control for size of a potential recipient with a variable for population from the Penn World Tables.[31] Diagnostics indicate that we do not need to be concerned with collinearity. In all our models, we lag our control variables one year behind our democracy aid measures to ensure that they precede the aid allocations.

To test our argument, we first present some descriptive data on the patterns of democracy aid during the period of our study. Then, consistent with the country-year structure of our data, we use Generalized Least Squares regression with random effects and corrections for a first-order autoregressive (AR1) process. Fixed effects are often the appropriate choice, but random effects are more appropriate for our study because they account for variations unique to a country but constant over time, and variance over time but constant across countries.[32] However, we also tested our GLS models with fixed effects. The results were fully consistent with our random effects findings, and we do not report them here.[33] We present a general test in which our dichotomous interest profile (low-high) variable is included with the other explanatory variables. Then, in what is the most important part of our analysis, we test the three-way conditional relationship in our argument by using this interest profile measure to split our sample into high and low interest subsamples to examine the effects of media attention, regime conditions and regime shifts, along with other factors. Splitting the samples is the appropriate step because our explanatory variables may vary by whether the potential recipient is of high or low interest, and using subsamples allows coefficients for all the explanatory variables to vary in each interest-level condition. In these tests, we include the measures for political, economic, and security interests. However, for robustness, and to ensure that our results are not a function of splitting the sample, we also conduct tests with the full sample and a three-way interaction among media attention, regime shift, and high-low interest profile.

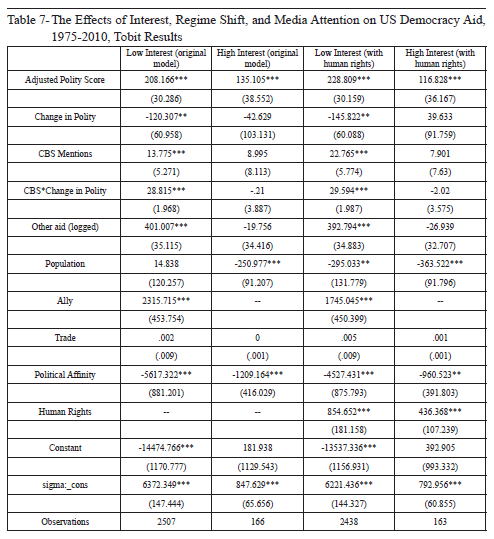

For robustness and to account for selection effects, we also conducted Tobit analyses of our models to further improve our confidence in the results. As a technique for addressing selection effects and censored data, Tobit is a useful option, especially for dealing with right- and left-censored data (ours is left-censored, with aid values bounded at 0). To further increase our confidence in our results, we also conducted this same suite of tests with Heckman selection models. These results were also consistent with our central findings, and we do not report them here.[34]

For both the GLS and Tobit models, we tested our original measures of media attention (New York Times and CBS Evening News), as well as a different measure of media attention: Gorman and Sequin’s (2015) measure of New York Times mentions of country leaders from 1950-2008. While this measure is narrower than ours, it provides another useful robustness check. All results are from STATA, version 14.

5.Results: Media Attention and US Democracy Aid

Our results support our novel argument. First, donor interest profile is consequential for democracy aid allocations (H1). Low-interest potential recipients received more democracy assistance than high-interest potential recipients. Second, media attention, regime conditions/shifts, and their interaction, along with other recipient characteristics and donor concerns, operate differently under specific conditions of donor interest, as we theorized (H2). Donor interests play a role alongside media attention, regime conditions/shifts, and their interaction, in shaping democracy aid allocations, but, most importantly, they first condition the effects of these dynamics. This three-way relationship is the central innovation of our study.

We begin with some general descriptive information for context.[35] Figure 1 provides context for US democracy aid, showing its marked increase after 1989. Figure 2 shows allocations of US democracy aid to different regime conditions (Polity IV measure of democracy-autocracy). The most autocratic regimes received only $312 per capita, while low and high anocratic regimes received $506 and $780 per capita, respectively. The most assistance went to unconsolidated democracies ($1036 per capita), while consolidated democracies received minimal democracy aid ($170 per capita). These simple results provide initial support for a key strand of our argument. They also further support our decision to exclude consolidated democracies from our analysis.

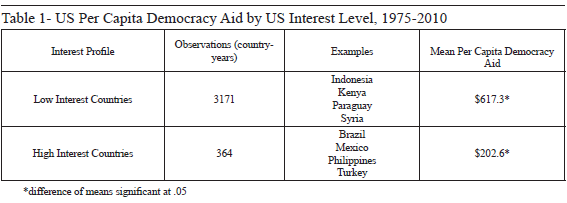

Table 1 presents a simple difference of means test of the relationship between interest profiles and per capita US democracy aid. Overall, countries of low interest receive more than three times the per capita democracy assistance than countries of high interest. This result provides initial support for our argument (H1).

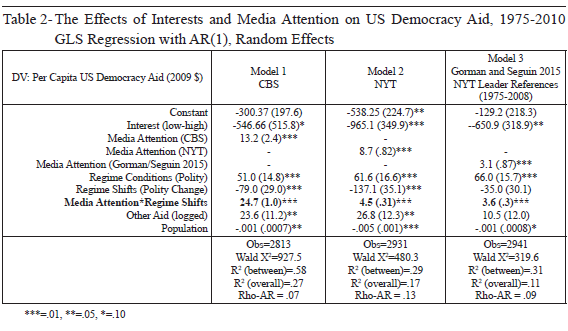

Table 2 presents the results of the first test of our model, with interest profile (low-high) included as an explanatory variable with our measures of media attention, regime conditions, regime shifts, and the interaction of media attention and regime shifts (controlling for other US aid and recipient population). These results provide support for H1. Overall, Table 2 shows good model fit and explanatory power. For our control variables, receipt of other aid generally results in greater democracy assistance (other aid is not statistically significant in Model 3 only), while larger countries (population) receive less. Even after controlling for these factors, the effects of our key variables are statistically significant and support our argument. Overall, there are four findings we wish to highlight.

First, the results show that the broad interest profile is a good predictor of per capita democracy aid allocations. In all three models, as we expected, countries of high interest receive less democracy aid than countries of low interest. Those effects range from $550 per capita to $965 per capita, depending on the model/measure of media attention.

Second, our results indicate that regime conditions, regime shifts, and media attention affect democracy aid. For regime conditions, the coefficients in all models are significant at the .05 level or better, indicating that, when media attention to a country is at zero, more democratic regime conditions tend to attract about $51-66 more in democracy aid per capita. Regime shifts are also significant at the .01 level in two of our three models, indicating that, in the absence of media attention, democratic changes reduce US democracy aid. Each point of shift toward democracy results in about $80-137 less per capita in democracy aid. This lends support to a stability argument: in the absence of visibility, political change appears to be regarded as a potential threat to other US interests and is, therefore, approached with caution.

Third, the results reveal that media attention has a statistically significant effect on democracy aid allocations when a potential recipient is not experiencing any regime shift. Models using our original measures of media attention as well as Gorman and Seguin’s measure show that increased media attention tends to result in greater allocation of democracy aid in the absence of regime shifts. The coefficients for media attention in Models 1-3 indicate that each mention results in between $3 and $13 more per capita in democracy aid.

Fourth, and most importantly, the results show that the interaction effects of media attention with regime shifts significantly affect democracy aid allocations, even when interest level (low-high) is included in the model. Whether our two original measures of media attention or that of Gorman and Seguin were used, the variable MEDIA ATTENTION*REGIME SHIFTS is significant at the .01 level in each model: additional media mentions at each point of regime shift toward democracy results in an additional $3-25 in per capita democracy aid, depending on the measure of media attention in the model.

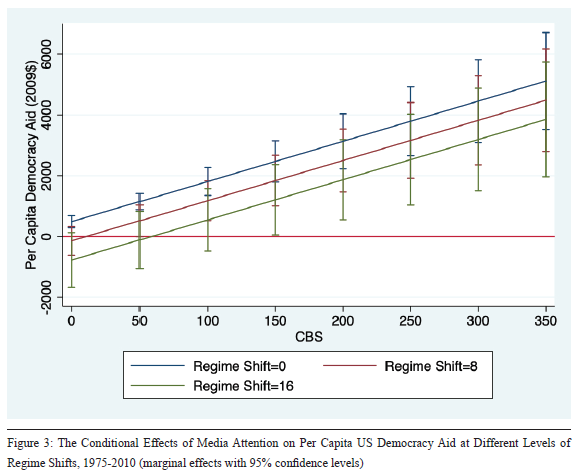

In Figure 3, we clarify and illustrate these results. The figure shows the marginal effects of media attention at specified values of regime shifts for both our original measures. As Figure 3 indicates, for countries experiencing regime shifts toward democracy, greater media attention results in more per capita democracy aid. Countries experiencing such shifts without media attention, however, do not. Increased media attention also appears to change democracy aid allocation strategies during regime shifts, moving allocations from negative to positive at certain thresholds of media attention (about 50 mentions by CBS, or 100 by the NYT).

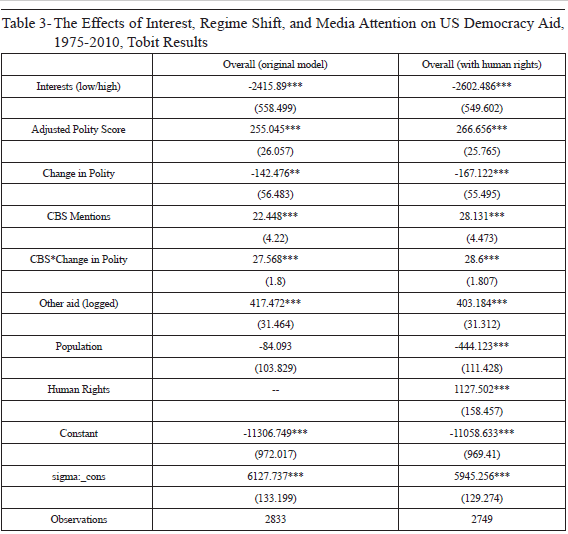

In Table 3, we present the results of our Tobit tests for this same basic model for our original measures of media attention. Even when modeling for selection effects, the same basic relationships hold. Interest level (low-high) is a statistically significant predictor of democracy assistance allocations, as is our critical media attention-regime shift variable. These results indicate the robustness of our results and increase our confidence in the findings. As previously noted, the fact that our supplemental tests using Heckman selection models produces the same results and inferences further reinforces our confidence in our results.

However, our central argument specifies a three-way relationship: the fundamental relationship between democracy aid allocations and the regime conditions, regime shifts, and media attention variables works differently in situations of diverging interest levels. Tables 2-3 and Figure 3 show that broad interest profile, media attention, regime conditions, and regime shifts affect the allocation of US democracy aid, and that the combination of regime shifts and media attention is a particularly potent cue, as we expected. But, as we argue in H2, interest profile (low-high) is not so much a factor shaping democracy aid allocations alongside these other variables as it is the factor that conditions the effect of these variables on democracy aid decisions. Indeed, we expected media attention to be a more powerful cue for democracy aid allocations in low-interest situations than high-interest situations. To gauge the conditioning effect of US interests, Tables 4-6 present the tests of our models in low-interest and high-interest subsamples, along with a three-way interaction model using the full sample. Across all the models in these tables, our results support our main argument (H2).

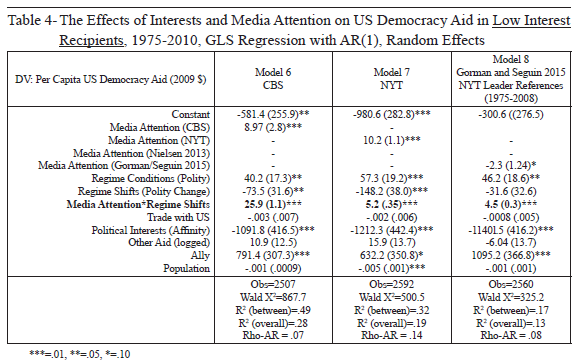

Table 4 shows the results of our model for low-interest potential recipients. Again, we test our model using both our original measures of media attention and Gorman and Seguin’s measure for robustness. These results strongly support our argument: media attention, regime conditions, regime shifts, and the interaction of media attention and regime shifts all provide powerful cues for the allocation of democracy aid in low-interest recipients.

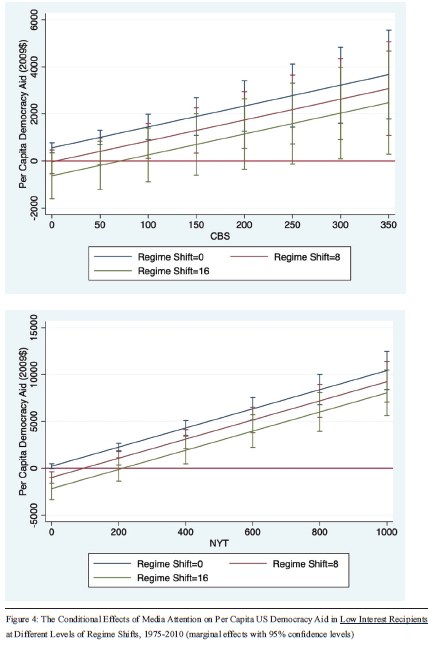

After controlling for factors related to US economic, political, and strategic interests in these low interest countries, the results in Table 4 show that democracy aid goes to countries with more democratic regime conditions. In addition, MEDIA ATTENTION (without regime shifts) generates greater democracy aid while REGIME SHIFTS (without media attention) generate less democracy aid. Most importantly, our key variable – MEDIA ATTENTION*REGIME SHIFTS – has a statistically significant and positive impact on democracy aid allocations. Notably, in all three model specifications in this low-interest subsample, additional media mentions at each point of regime shift toward democracy results in an additional $4.5-26 in per capita democracy aid. Thus, where US interests are low, media attention highlights, clarifies and amplifies the nature of regime shifts, interacting with them to provide aid allocators with cues that lead them to allocate more democracy aid.

For these low-interest countries, the two panels of Figure 4 show the marginal effects of media attention on democracy aid at different levels of regime shift. Even big changes – normally a cause for hesitation for US policymakers because of stability concerns – are eventually met with increased democracy aid when media attention is greater, with 65-70 (CBS) or 200 (NYT) media mentions being the thresholds at which aid increases start for those countries experiencing the largest, most dramatic regime shifts.

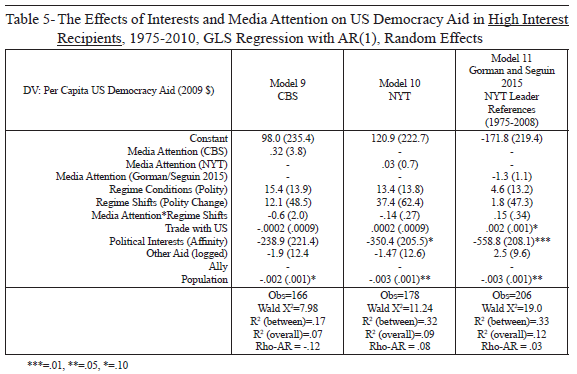

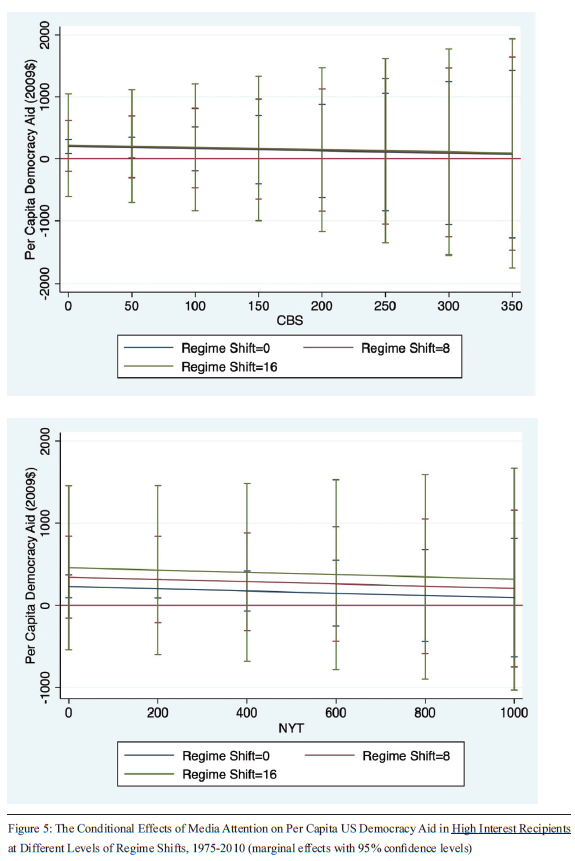

We do not expect this same dynamic to occur in high-interest countries, where policymakers are already engaged and attentive and do not rely on media attention for cues about whether or not to provide democracy aid. Thus, we do not expect to see our key measures impact democracy aid allocations in this positive fashion. Table 5 presents the results of our tests in our high-interest subsample. As these results show, our key variables no longer have any statistically significant effect on democracy assistance, as expected. Regime conditions, regime shifts, media attention, and the interaction of media attention with regime shifts all fail to reach standard levels of statistical significance in this subsample. As the two panels of Figure 5 show, the positive conditional effects of media attention on democracy aid at different levels of regime shift for low-interest recipients simply disappear for high-interest countries.

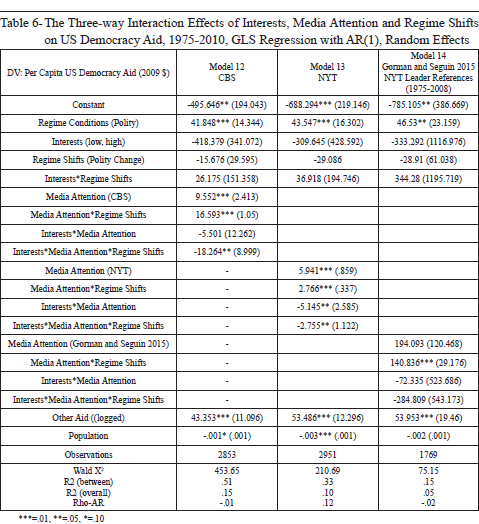

As previously discussed, we believe a split-sample approach is the correct approach given our argument. However, to ensure that this decision has not unduly influenced our results, we also conducted tests with the three-way interaction, which we present in Table 6. As Table 6 shows, these results also support our findings and inferences. The key variables (bolded in the table) all remain statistically significant and in the theorized direction: in particular, the interactions show that MEDIA ATTENTION*REGIME SHIFTS increases democracy assistance in low interest countries but decreases it in high interest countries.

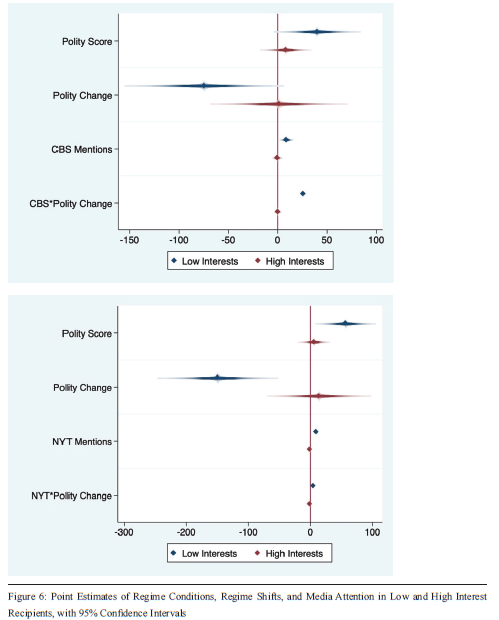

The two panels in Figure 6 present point estimates of the key variables in side-by-side comparison of low-interest recipients (blue points) and high-interest recipients (red points), with smoothed error bands for each. As this figure shows, our variables of interest – regime conditions (polity score), regime shifts (polity change), media attention (CBS and NYT mentions), and the interaction of media attention and regime shifts (CBS/NYT mentions*Polity change) – are significant indicators in low-interest situations, but not in high-interest situations. This further confirms the central hypothesis (H2) of our theory.

Finally, Table 7 presents the results of our tests with Tobit models for the CBS and NYT measures of media attention in the two subsamples. These results further support our argument. In the low-interest subsample, our Tobit models perform as expected, consistent with the results for the low-interest subsample in Table 4. In the high interest subsample, once again the media-attention-regime shift interaction is not a statistically significant predictor at either stage. Again, the consistency of our results in this technique increases our confidence in the robustness of our argument.

6. Conclusions: Donor Interests, Media Attention and Democracy Aid

Our examination of US democracy assistance from 1975-2010 demonstrates the conditioning effects of donor interest profile on the relationship between media attention and democratic demand/feasibility concerns. Overall, the results extend previous studies concluding that democracy aid allocations are strategic bets affected by regime conditions/shifts and media attention, which serve as important cues on the likelihood of progress toward/consolidation of democracy and the potential for democracy aid to impact democratization positively. As others have concluded, the visibility generated by media attention works in tandem with indicators of movements toward democracy to trigger increased democracy aid allocations.

However, our results clearly and robustly show that this central dynamic functions very differently in low-interest versus high-interest profiles. This is the central focus and the primary contribution of our study. Put another way, it is not simply that donor interests shape democracy aid allocations, it is that differentials in donor interests condition the way that media attention and regime shifts shape democracy aid allocations. When potential democracy aid recipients have high interest profiles for donors such as the United States, the cueing effect of media attention and regime shifts is far less important to aid allocations than in low interest profiles. In effect, when US policymakers are most engaged (high interest profiles), democracy aid allocations are driven by cues other than movements toward democracy and media attention.

Our results reinforce findings that US policymakers strategically consider the likelihood of successful democratization along with regime conditions and regime shifts as critically important indicators when allocating democracy aid. Moreover, the evidence shows that how US democracy aid allocators respond to increased media attention and regime shifts within a potential recipient country primarily depends upon the level of US interest. This underscores an important dynamic: the agenda-setting power of the media is most pronounced when potential recipient states are less salient for US policymakers, but less pronounced when potential recipient states are more salient. Thus, the power and influence of the news media in democracy aid decisions depends upon the extent to which a potential recipient is already on the radar for US policymakers.

Future studies might include other sources of media attention (especially given the dramatic changes in the nature of the media over the past two decades or so), other forms of agenda-setting (i.e., non-media), and other donors beyond the United States. Research should also examine the context (and valence) of country mentions in news coverage to better assess the relationship between media attention and democracy aid decisions. Not all country mentions are equal and unpacking such context is potentially important.

Additionally, future research might consider disaggregating the data to account for the following dynamics. First, different foreign policy and global contexts may well be significant, so examining the Cold War, post-Cold War, and post-9/11 periods might reveal variation in the linkages between democracy aid and the interests-media-regime factors on which we focus. Further study of our key conditional variable – interests – might prove fruitful as well. Our analysis and modeling focus on broad interest profiles constructed by indexing across economic, political and security interest areas. However, examination of each of these interest areas individually might reveal more subtle nuances and variations in the central relationships of our study. Does media attention work the same way in areas of high(low) economic, political and security interests? Furthermore, regional variations in these allocation decisions might also be investigated as well. Finally, select case-studies might scrutinize the process and causal mechanisms at work in these dynamics.

Nevertheless, our results indicate that donor interest profiles are a crucial conditioning factor shaping the impact of media attention. Thus, while the link between media attention and regime shifts could be interpreted as a modified version of the “CNN Effect” in which the media plays an important role in shaping policymaker decisions on democracy aid, this cueing function is substantially muted when donor interests are high. In those circumstances, US officials do not appear to look to or rely upon media attention to shape how they allocate democracy aid to potential recipients around the world.

Alesina, Alberto, and David Dollar. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why.” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (2000): 33–63.

Apodaca, Clair, and Michael Stohl. “United States Human Rights Policy and Foreign Assistance.” International Studies Quarterly 43 (1999): 185–98.

Askarov, Zohid, and Hristos Doucouliagos. “Does Aid Improve Democracy and Governance? A Meta-regression Analysis.” Public Choice 157 (2013): 601–28.

Balla, Eliana, and Gina Yannitell Reinhardt. “Giving and Receiving Foreign Aid: Does Conflict Count?” World Development 36 (2008): 2566–585.

Bailey, Michael A., Anton Strezhnev, and Erik Voeten. “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. 61, no. 2 (2017): 430–56.

Barbieri, Katherine, and Omar M. G. Keshk. “Correlates of War Project Trade Data Set Codebook.” Version 3.0. 2012. http://correlatesofwar.org.

Baum, Matthew, and Philip B. K. Potter. War and Democratic Constraint: How the Public Influences Foreign Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. Agendas and Instability In American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Beck, Nathaniel. “Time-Series-Cross-Section Methods.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier. London: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bell, Sam R., K. Chad Clay, and Carla Martinez Machain. “The Effect of US Troop Deployments on Human Rights.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 10 (2017): 2020–042.

Blanton, Shannon Lindsey. “Foreign Policy in Transition: Human Rights, Democracy, and U.S. Arms Exports.” International Studies Quarterly 49 (2005): 647–67.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. “Foreign Policy and Policy Concessions.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (2007): 251–84.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: Mit Press, 2003.

Cingranelli, David L., and Thomas E. Pasquarello. “Human Rights Practices and the Distribution of U.S. Foreign Aid to Latin American Countries.” American Journal of Political Science 3 (1985): 539–63.

Demirel-Pegg, Tijen, and James Moskowitz. “U.S. Aid Allocation: The Nexus of Human Rights, Democracy, and Development.” Journal of Peace Research 46 (2009): 181–98.

Dietrich, Simone. “Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocations.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2013): 698–712.

–––. “Donor Political Economies and the Pursuit of Aid Effectiveness.” International Organization 70 (2016): 65–102.

Dietrich, Simone, and Joseph Wright. “Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa.” Journal of Politics 77 (2015): 216–34.

Drury, A. Cooper, Richard Olson, and Douglas Van Belle. “The CNN Effect, Geo-Strategic Motives and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance.” Journal of Politics 67 (2005): 454–73.

Edy, Jill A., Scott L. Althaus, and Patricia F. Phalen. “Using News Abstracts to Represent News Agendas.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82, no. 2 (2005): 434–46.

Fariss, Christopher J. “Respect for Human Rights has Improved Over Time: Modeling the Changing Standard of Accountability.” American Political Science Review 108, no. 2 (2014): 297–318.

Finkel, Steven E., Aníbal Pérez-Liñán and Mitchell A. Seligson. “The Effects of U.S. Foreign Assistance on Democracy-Building, 1990-2003.” World Politics 59 (2007): 404–39.

Gibler, Douglas M. International Military Alliances, 1648-2008. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2009.

Gibney, Mark, Linda Cornett, Reed Wood, and Peter Haschke. “Political Terror Scale 1976-2012.” 2013. http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/.

Gilboa, Eytan, Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert, Jason Miklian and Piers Robinson. “Moving Media and Conflict Studies beyond the CNN Effect.” Review of International Studies 42, no. 4 (2016): 654–72.

Golan, Guy. “Inter-Media Agenda-Setting and Global News Coverage: Assessing the Influence of the New York Times on Three Network Television Evening News Programs.” Journalism Studies 7, no. 2 (2006): 323–34.

Gorman, Brandon, and Charles Seguin. “Reporting the International System: Attention to Foreign Leaders in the US News Media, 1950–2008.” Social Forces 94, no. 2 (2015): 775–99.

Heinrich, Tobias. “When is Foreign Aid Selfish, When is it Selfless?” Journal of Politics 75, no. 2 (2013): 422–35.

Heinrich, Tobias, and Matt W. Loftis. “Democracy Aid and Electoral Accountability.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63 (2017): 139–66.

Heinrich, Tobias, Yoshiharu Kobayashi, and Leah Long. “Voters Get What They Want (When They Pay Attention): Human Rights, Policy Benefits, and Foreign Aid.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (2018): 195–207.

Kalyvitis, Sarantis, and Irene Vlachaki. “Democratic Aid and the Democratization of Recipients.” Contemporary Economic Policy 28 (2010): 188–218.

Kersting, Erasmus, and Christopher Kilby. “Aid and Democracy Redux.” European Economic Review 67 (2014): 125–43.

Kono, Daniel Yuichi, and Gabriella R. Montinola. “Does Foreign Aid Support Autocrats, Democrats, or Both?” Journal of Politics 71 (2009): 704–18.

Lebovic, James H. “National Interests and U.S. Foreign Aid: The Carter and Reagan Years.” Journal of Peace Research 25 (1988): 115–35.

Linsky, Martin. Impact: How the President Affects Federal Policymaking. New York: W.W. Norton, 1986.

Livingston, Steven, and Todd Eachus. “Humanitarian Crises and U.S. Foreign Policy: Somalia and the CNN Effect Reconsidered.” Political Communication 12, no. 4(1995): 413–29.

Marshall, Monty, and Keith Jaggers. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2011.” 2012. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm.

McKinlay, Robert D., and Richard Little. “A Foreign Policy Model of U.S. Bilateral Aid Allocation.” World Politics 30 (1977): 58–86.

McNelly, John T., and Fausto Izcaray. “International News Exposure and Images of Nations.” Journalism Quarterly 63, no. 3(1986): 546–53.

Meernik, James. U.S. Foreign Policy and Regime Instability. US Army War College: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008.

Meernik, James, Eric L. Krueger and Steven C. Poe. “Testing Models of U.S. Foreign Policy: Foreign Aid During and after the Cold War.” Journal of Politics 60 (1998): 63–85.

Munck, Gerardo L., and Jay Verkuilen. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (2002): 5–35.

Nielsen, Richard. “Rewarding Human Rights? Selective Aid Sanctions against Repressive States.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (2013): 791–803.

Nielson, Richard, and Daniel Nielson. “Triage for Democracy: Selection Effects in Governance Aid.” Paper presented at the Department of Government, College of William & Mary, February 5, 2010.

Norris, Pippa. “The Restless Searchlight: Network News Framing of the Post-Cold War World.” Political Communication 12 (1995): 357–70.

Palmer, Glenn, Scott B. Wohlander, and T. Clifton Morgan. “Give or Take: Foreign Aid and Foreign Policy Substitutability.” Journal of Peace Research 39 (2002): 5–26.

Paquin, Jonathan. A Stability-Seeking Power: U.S. Foreign Policy and Secessionist Conflicts. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2010.

Peksen, Dursun, Timothy M. Peterson, and A. Cooper Drury. “Media-driven Humanitarianism? News Media Coverage of Human Rights Abuses and the Use of Economic Sanctions.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (2014):855–66.

Peterson, Timothy, and James M. Scott. “The Democracy Aid Calculus: Regimes, Political Opponents, and the Allocation of U.S. Democracy Assistance, 1975-2009.” International Interactions. 44, no. 2 (2018): 268–93.

Pew Research Center 2009. “State of the news media 2009.” Accessed May 15, 2012.

http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1151/state-of-the-news-media-2009.

Plumper, Thomas, and Eric Neumayer. “The Level of Democracy during Interregnum Periods: Recoding the polity2 Score.” Political Analysis 18 (2010): 206–26.

Poe, Steven C. “Human Rights and Economic Aid Allocation under Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (1992): 147–67.

Scott, James M., and Carie A. Steele. “Sponsoring Democracy: The United States and Democracy Aid to the Developing World, 1988-2001.” International Studies Quarterly 55, no. 1(2011): 47–69.

Scott, James M., Charles M. Rowling, and Timothy M. Jones. “Democratic Openings and Country Visibility: Media Attention and the Allocation of US Democracy Aid, 1975-2010.” Foreign Policy Analysis 16, no. 3 (2020): 373–96.

Scott, James M., and Ralph G. Carter. “Distributing Dollars for Democracy: Changing Foreign Policy Contexts and the Shifting Determinants of U.S. Democracy Aid, 1975-2010.” Journal of International Relations and Democracy 22, no. 3(2019): 640–75.

Strezhnev, Anton, and Erik Voeten. “United Nations General Assembly Voting Data.” Harvard Dataverse, V7, 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/12379.

Swedlund, Haley. The Development Dance: How Donors and Recipients Negotiate the Delivery of Foreign Aid. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Tierney, Michael J., Ryan Powers, Dan Nielson, Darren Hawkins, Timmons Roberts, Mike Findley, Brad Parks, Sven Wilson, and Rob Hicks. “More Dollars than Sense: Refining Our Knowledge of Development Finance Using AidData.” World Development (2011): 1891–906.

Van Belle, Douglas A. “Bureaucratic Responsiveness to the News Media: Comparing the Influence of New York Times and Network Television News Coverage on U.S. Foreign Aid Allocations.” Political Communication 20 (2003): 263–85.

Van Belle, Douglas, Jean Sebastien Rioux, and David M. Potter. Media, Bureaucracies and Foreign Aid. Palgrave: New York, 2004.

Wang, Xiuli, Pamela J. Shoemaker, Gang Han, and E. Jordan Storm. “Images of Nations in the Eyes of American Educational Elites.” American Journal of Media Psychology 1, no. 1/2 (2008): 36–60.

Zhang, Cui, and Charles William Meadows III. “International Coverage, Foreign Policy, and National Image: Exploring the Complexities of Media Coverage, Public Opinion, and Presidential Agenda.” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 76–95.

Ziaja, Sebastian. “More Donors, More Democracy.” Journal of Politics 82, no. 2 (2020): 433– 47.