Ioannis Nioutsikos

University of the Peloponnese

Konstantinos Travlos

University of the Peloponnese, Özyeğin University

Magdalini Daskalopoulou

University of the Peloponnese

The most recent surveys on the study of the connection between mutual military buildups, arms races, and military interstate disputes (MID) warn of research projects, especially in the case of the Greece-Turkey dyad, that have reached a stalemate. This is due to the difficulty of capturing motivations, which constitute the main variable that turns mutual military buildups into arms races. Using the Greece-Ottoman Empire and Greece-Turkey dyads as proof-of-concept cases, we advance a novel approach for analyzing the interrelation between mutual military buildups, arms races, and MIDs that can overcome that stalemate. We suggest a two-stage approach that focuses on the dyad as a unit of analysis. In the first stage, which we preset here, we use rivalry to divide dyad history into periods of differing subsistence military spending. We then locate periods of mutual military buildups in the different rivalry periods of a dyad history. We argue that this process provides a more nuanced and detailed grasp on the presence of mutual military buildups in a dyad. It also provides the foundation for the future second stage of analysis, where qualitative research can focus on the specific periods of mutual military buildups to unearth indicators of motivation.

1. Introduction*

The debate on the interaction of arms races and mutual military buildups with the onset of militarized interstate disputes (MID) and their escalation to war seems to have reached a stalemate.[1] The use of strategic rivalry as a proxy for the motivations that transform mutual military buildups to arms races seems to have settled the task of capturing the relationship between these variables.[2] And yet, it does not answer the question of how strategic rivalry transforms mutual military buildups to arms races. To assume that strategic rivalry denotes arms-race motivations in mutual military buildups would be to wield a brush too broad to permit us to advance the study of the relationship between arms races, mutual military buildups, militarized interstate disputes, and war. In this article, we use a case-focused analysis to present an alternative way to leverage rivalry analysis to locate mutual military buildups. Our method provides a richer picture of the distribution of mutual military buildups within the history of a dyad, one accounting for variation in rivalry intensity. This, in turn, can be a foundation for qualitative studies that can locate those mutual military buildups which are characterized by arms race motivations.

We use the Greece-Turkey/Ottoman Empire dyads as our case study. Rather than proxy motivation for arms races via strategic rivalry, we argue that rivalry levels, as conceptualized within the Peace Scale, can facilitate the capture of different levels of subsistence spending within a dyad.[3] As we argue based on a review of the econometric Arms Race literature on the Greece-Turkey case, this is an important basic threshold to account for when looking for the above-average spending that might indicate arms races.[4] Using military expenditures, military expenditures per capita of military personnel, and data based on the National Military Capability data set from Correlates of War, we calculate within each period of the dyad for each party the annual average rate of change.[5] This way, we capture the variation in subsistence military spending as driven by variation in rivalry intensity. Then we locate increases in the rate of change that were above the rivalry period average. Where those overlap between the dyad members, we argue that we have a mutual military buildup. We then use that data to provide a descriptive analysis of the contemporaneity of militarized interstate dispute onset with periods of mutual military buildups in the Greece-Turkey/Ottoman Empire dyads.

The resulting data captures some cases of mutual military buildups missed in previous operationalizations. It also covers a much larger period of interest than previous research by including the 19th century (1828–1900). Our descriptive findings concerning the presence of periods of mutual military buildups largely agree with the existing literature, and we aim to advance the research on the subject by offering more precision and flexibility. That said, we argue that our method is but the start for the process of locating arms races. We argue that quantitative methods by themselves simply cannot differentiate those mutual military buildups that become arms races from those that do not. A review of the econometric literature on arms races in the Greece-Turkey case reveals the limits of such an endeavor. Instead, our method provides a much more precise and rich foundation for qualitative work that will unearth the motivations that render statistical mutual military buildups into arms races.

Our argument is laid forth as follows. We first review the existing literature on mutual military buildups, arms races, and their associations with MIDs and war. We also review the econometric arms races literature on the Greece-Turkey dyad. We then discuss our use of the concept of rivalry, our operationalization of rivalry periods, and then our operationalization of mutual military buildups. We then present the descriptive analysis of the data and conclude with remarks on further research.

2. Arms Races, Military Buildups, and Militarized Interstate Disputes

One of the first definitions of arms races offered was by Samuel Huntington, who defined them as “a progressive, competitive peacetime increase in armaments by two states or coalitions of states resulting from conflicting purposes and mutual fears.” Huntington also made an original contribution to the literature by distinguishing arms races in the quantity from those in the quality of armaments.[6] In addition, fundamental to the idea of arms races is their strategic character: arms races are purposeful and targeted.

A central debate in the research on the relationship between arms races and war onset exists between those scholars that argue that wars are the result of a process of deterrence failure and those that argue that they are the result of a process of conflict spiral.[7] For the first group, arms races become a secondary variable within the process that leads to war, but do not cause war per se, which is instead driven by structural factors. The exception may be an association of arms races with preventive war motivations concerning the timing of war.[8] It is in this role that arms races also concern the power-transition scholarly tradition.[9] For the second group, any discussion of arms races became absorbed into debates about the offense/defense balance, a debate that has now lost a lot of its luster since no breakthrough has been made on the question of how to define a weapon system as defensive or offensive.[10]

An important research strand has been the examination of the theoretical dimensions of the arms race phenomenon and its relationship with the outbreak of war from a historical standpoint. For instance, David Stevenson explored the competition in armaments procurement of six European Powers and how it inhibited the management of the crisis prior to the outbreak of the First World War.[11] David Herrmann focused on the land armaments race during the same period and described how it made war a more probable outcome.[12] Joseph Maiolo examined the arms race among the great powers between 1931 and 1941 and explained how it contributed to the outbreak and the expansion of the Second World War.[13] Finally, the collective volume Arms Races in International Politics re-examined the theoretical foundations of arms races studies through a primarily historical body of research that explored cases from around the globe from before 1914 until the post-Cold War period.[14]

The difficulty of ascertaining arms race motivations in the study of international relations has meant that many scholars have opted to focus more on the observable elements of a potential arms race rather than on the unobservable motivations. This strand of research began with the work of Lewis Richardson.[15] The advent of the Correlates of War data set permitted a new generation of scholars to work on arms races based on quantitative indicators, though initial studies were inconclusive.[16] A central concept in this literature was the move from the idea of arms races to “mutual military buildups.”[17] This was a result of the inability of quantitative methods to capture the motivation element of arms races.

The central difference between the concept of arms race and the concept of mutual military buildup is the confidence we have in the presence of strategic motivations. An arms race is a mutual military buildup that we know is driven by competitive strategic motivations between the two sides. If we do not know this, then all we can speak of is a quantitative mutual military buildup. Thus, the mutual military buildups we see among countries might not be driven by strategic concerns but may just be the result of coincidence. This is especially likely with cases of states with multiple opponents, or during periods of general increases in arms spending globally due either to major multiparty wars or to changes in military doctrine and technology.

The independence of the concept of mutual military buildups from motivations has made them the preferred tool for quantitative studies. This is especially the case in research conducted under the conflict-spiral model of war onset, where inadvertent war onset is possible. In this case, the pursuit of security by two states via arming leads to the exacerbation of the security dilemma and the rise of preventive war motivations among decision-makers due to psychological effects captured by stimulus-response theory.[18] A fundamental element of these approaches is that mutual military buildups and the arms races they give rise to, can foster willingness for war independently of other factors that lead to war.[19] Working within the Steps to War analytical framework, Vasquez and Senese found indicators that arms races in the pre-nuclear era had a strong independent influence on the escalation of militarized disputes (MID) to war.[20]

The measurability of military buildups sparked a robust debate on their association with the onset of war. The conclusion was that without a theory that can clarify exactly when arms races have an independent influence on war onset, little traction could be gained on this research.[21] That said, the work of Susan Sample provided important findings on the statistical association of arms races with war onset. First, among major powers, arms races are associated with war onset within the logic of the conflict spiral model of war, but only for the pre-1945 period.[22] The later inclusion of minor powers largely reinforced her findings about the different association of arms races with war onset before and after 1945, but also found that, statistically, arms races between minor and major powers were unlikely to be associated with war onset.[23]

The findings by Sample were a great contribution to the field but did not resolve the question of motivation. Indeed, we can criticize the existing literature of “jumping the gun” by treating mutual military buildups as the result of arms race motivations and seeking to proxy motivations via the presence of other conflict-fostering factors, or conditions that cause both arms races and war onset. The most important such factor used is interstate rivalry.[24] In this approach, mutual military buildups do not lead to arms races that contribute to the onset of war. Instead, the transformation of mutual military buildups to arms races is an epiphenomenon of underlying conflictual conditions encapsulated in the concept of interstate rivalry.

This school of thought has located findings that arms races are highly associated with the onset of MIDs and war when they take place within a strategic rivalry.[25] These findings address both the willingness element (rivalry) and the opportunity element (arms races) leading to war.[26] The evolution of this research led to findings that arms races have a secondary but still important role in fostering war within rivalry.[27] On the other hand, Sample found indicators that before 1946, mutual military buildups have an association with escalation of MIDs to war, independent from rivalry.[28] Her work indicates that operationalization of rivalry and periodization between and within dyads are crucial elements in any explanation.

Further research found indicators that point to an interactive effect were rivalries are sometimes associated with mutual military buildups, but are not caused by them.[29] That said, a major review of the field noted that there is a lack of theory about why arms races can lead to war and how arms races and rivalry might be associated, as well as a widespread lack of empirical testing of any articulated theories, such as stimulus-response theory.[30] Furthermore, there has not been enough connection between the studies of what Huntington calls quantitative and qualitative arms races.

The general findings of the mutual military buildup literature already have established at least some statistical association between mutual military buildups and the escalation of MIDs to war. If one accepts that the presence of strategic rivalry resolves the issue of motivations, then a question arises regarding what extra insights are gained by bringing in qualitative research to clarify motivations. First, as we argue throughout the paper, we cannot rely on strategic rivalry as a proxy for motivations for arms races. Rivalry, instead, permits us to capture variations in subsistence spending. Second, motivations are paramount in the analysis of the path to war when using the conflict spiral framework. The dangers of arms races are that they feed into preventive war motivations, or lead decision-makers down the path of inadvertent war. Quantitative studies can provide the framework telling us where to look for motivations, but only qualitative studies can make the persuasive case of whether the mutual military buildups were motivated by dyadic strategic interaction, and how they impacted decision-making.

Let us give an example of this dynamic. The defeat of the Ottoman Navy by the Greek Navy in the First Balkan War was the direct motivation for an ambitious naval procurement program aimed at gaining two dreadnought battleships. The successful signing of contracts led to a crisis for Greek decision-makers. This led to two results, one that might be caught by quantitative analysis and one that would be hidden. The Greek government, in turn, also made its own orders. However, because the Greek dreadnoughts would arrive after the Ottoman ones, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos and Chief of the General Headquarters Staff Ioannis Metaxas began seriously exploring a preventive war option against the Ottoman Empire.[31] The only reason the war did not take place is because of the onset of the First World War, which saw the ready Ottoman dreadnoughts confiscated by the UK for its own fleet. Here we have a classical stimulus-response dynamic, where military procurement is driven by the activity of a rival, and in turn, that procurement leads to the rise of preventive war motivations. Quantitative analysis would only capture part of the story, missing the crucial preventive war motivations, which did not lead to war only due to random luck.

When it comes to the specific cases of Greece and the Ottoman Empire, and Greece and Turkey, the existing quantitative research has produced different results concerning the existence of mutual military buildups. One set of scholars has located mutual military buildups preceding MIDs in the 1975–1978 period, which they consider possible candidates for being arms races.[32] Another period of mutual military buildups in the 1934–1936 period is not considered a possible arms race. On the other hand, others have not found any indicators of mutual military buildups in the whole history of the Greece-Turkey/Ottoman Empire dyad.[33] A recent study focusing on the 1985–2020 period did argue that at least Turkish air incursions into Greek airspace, a form of MID, are driven by increased Turkish military capabilities, positing some connection between military buildups, mutuality, and increased MID engagement.[34]

The suggestion that the Greek-Ottoman Empire dyad is relatively free of arms races, despite the four interstate wars, multiple MIDs, and some clear examples of qualitative arms races (the 1912–1914 dreadnought naval race), is surprising. This ambiguity in findings is also characteristic of a more robust econometric tradition studying the post-1950 Greek-Turkish relationship.

This tradition developed independently of the mutual military buildups debate, and neither literature cited the other. The most important review of the literature produced by the econometric tradition was conducted by Brauer, who reviewed a decade’s worth of work on the Greek-Turkish case based on Richardson’s Action-Reaction Model.[35] Their review is not thorough, as it excludes the earlier foundational works by Antonakis and Majeski, which are partly reviewed by Avramides.[36] Brauer concluded that the econometric literature exploring arms race dynamics since the 1950s–1960s had reached the point of diminishing returns, and any future breakthroughs would have to rest on enriching the political, strategic, and economic factors considered. Indicators of an arms race in the period starting from 1960 and going on to the mid-1980s are there, as well as further indicators that Greece was reacting to Turkish spending in that period, but that is all that has been found.[37]

We are not addressing this econometric arms race tradition in this paper. The reasons for that are that a) it is almost exclusively focused on the post-1960s period of the Greece-Turkey dyad, and b) there is little to add to the findings. As Brauer pointed out, that literature has reached the point of diminishing returns. Instead, our interest here is to take the concepts of mutual military buildups, and using the Greece-Ottoman Empire and Greece-Turkey dyad cases, propose a different way to locate mutual military buildups within varying conditions of interstate rivalry.

But there are key insights from that literature that we will also use in our approach in this paper. This includes the use of military expenditures per capita (of military personnel) as a proxy for spending on qualitative elements of military power, and the need to account for subsistence spending.[38] Using per capita military expenditures is the tool the econometric literature used in order to capture qualitative spending in military forces, such as training or spending on command-and-control reform. While not a perfect measure, it is the one used by the literature. Subsistence spending is important because domestic factors other than international security concerns, as well as more general trends in military technology and technique, may lead to multiple states increasing their military expenditures at the same time for reasons other than potential security competition. The threshold is needed in order to help locate those mutual expenditure increases that may be driven by attempts to gain military advantages over other states and are thus more likely to lead to arms races.

From the mutual military buildups literature, we find the attempt to proxy arms race motivations in mutual military buildups via the concept of strategic rivalry a useful but problematic waypoint.[39] We find it problematic because the way the concept of strategic rivalry is built can lead to extremely long periods of rivalry, as is the case in the Greek-Ottoman/Turkish cases. The lack in variation of motivation contrasted with the variation in the presence of mutual military buildups tends to weaken the motivational connection between strategic rivalry and escalation of mutual military buildups into arms races. We do accept that integrating rivalry into the exploration of the occurrence of mutual military buildups and their escalation to arms races is a key to moving forward in the study of the connection between arms races and onset of military conflict. We only suggest a different way of doing it.

In the next section, we discuss the concept of rivalry and how we use it in the Greece-Ottoman Empire and Greece-Turkey cases.

3. Rivalry as a Catalyst

The two dominant ways to operationalize interstate rivalry are the one pioneered by Goertz and Diehl, and the Strategic Rivalry concept pioneered by Thompson, Colaresi, and Rasler.[40] The main difference in the two concepts is operationalization. The Goertz-Diehl concept is based on observed behavior, as well as the presence of factors that foster conflict in a relationship, including but not limited to frequent MIDs. The strength of the Goertz-Diehl concept is that it is a replicable measure. The main problem is that because occurrence of disputes is part of the operationalization process, this concept cannot be used to explain dispute occurrence, only escalation to war. The Strategic Rivalry concept, on the other hand, is based on qualitative estimations of perceptions of enmity among decision makers. The problem with this is that the operationalization process is not easily replicable. However, it does permit the evaluation of the relationship between rivalry and onset of disputes, not just wars.

The Goertz-Diehl concept received further progressive development, with the two concepts of interstate and strategic rivalry becoming integrated in the Peace Scale, the most up-to-date operationalization of the concepts.[41] In the Peace Scale, the Goertz-Diehl conception of Rivalry falls within the category of Severe Rivalry, the most war-prone condition, while strategic rivalries are part of the concept of Lesser Rivalry.[42] After that, there are the conditions of Negative Peace, Warm Peace, and Security Community. These conditions will facilitate the periodization of the present study and will provide good testing grounds for the effect of rivalry on mutual military buildups and arms races.

A prominent theme in both the qualitative and the quantitative literature of arms races is the study of specific countries during a particular timeframe.[43] In a similar fashion, the present study focuses on the case of Greece and the Ottoman Empire/Turkey from 1828 until the present. Under the Goertz-Diehl concept of rivalry, the interstate history of Greece and the Ottoman Empire, and then Turkey, was characterized by two periods of Severe Rivalry. Between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, this is the period 1866–1925. The period from 1925 to 1934 is categorized as a period of transformation in the relationship. The period from 1934 to 1957 is considered a period of Negative Peace. Then, from 1957 to the present, we again have a period of Severe Rivalry. Do note that the Peace Scale is coded for the 1900–2015 period. But prior work by Goertz and Diehl had noted a Severe Rivalry active between 1866 and 1925.[44]

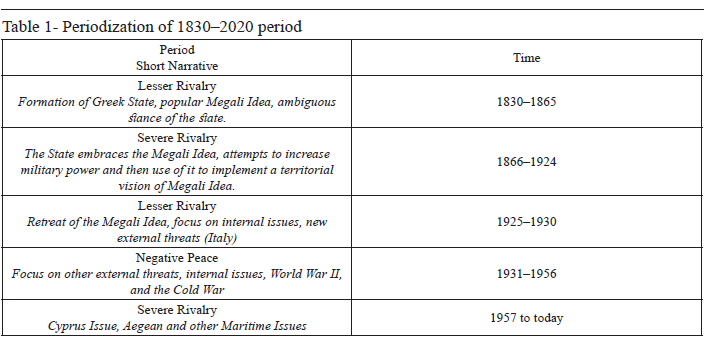

What about the period before 1866? Here, the concept of Strategic Rivalry provides an answer, which can be integrated into the Peace Scale. Again, two periods exist. From 1827 to 1930, there was a Strategic Rivalry between Greece and the Ottoman Empire/Early Turkish Republic, and then, between 1955 and today, there was one between Greece and Turkey. The strategic rivalry from 1955 to today is absorbed by the Severe Rivalry concept for the same period, but the earlier Strategic Rivalry nicely captures a reality of early Greek politics. The Ottoman Empire was seen as the foe, but until the Great Cretan Revolution of 1866–1869, willingness to pursue a military policy for this goal was absent or weak. We can thus separate the interstate period of Greek-Turkish relations as follows:

Table 1- Periodization of 1830–2020 period

There is thus a good deal of variation in the presence or absence of the rivalry condition within the case study that can provide good testing grounds for the effect of rivalry on mutual military buildups. This periodization also provides a natural control variable for the influence of rivalry on the onset of mutual military buildups, and the onset of arms races. We thus break from the post-1950 focus of most existing studies of the Greek-Turkish case. We do this because we are confident that the pre-1950 period could be a useful control period for dynamics of the post-1950 period. More importantly, the pre-1950 period, and especially the 1865–1924 Severe Rivalry and the 1925–1930 Lesser Rivalry, may not be independent from the 1954–present Severe Rivalry. Instead, we may be dealing with a case of an interrupted rivalry that started in 1828 and continues with interruptions.[45]

4. Measuring Mutual Military Buildups

Our approach to locating mutual military buildups is based on the military expenditures and military personnel data within the Correlates of War National Military Capabilities data set.[46] This is the military expenditure data used by the quantitative literature focusing on mutual military buildups. It is not used in the econometric literature on arms races. We use this for the following reasons: 1) we want to make sure that the method we are proposing here can be applied to dyads outside the Greece-Ottoman Empire/Turkey cases, and that the data covers many states in the interstate system; 2) the data covers the pre-1945 period and thus the whole period of interest for us. The coverage of Greece is fairly complete, and adequate for Turkey, while for the Ottoman Empire, there is information lacking for stretches of time during the 19th century, but not to the point of rendering the data unusable.

Using that data, we built a data set with a county year unit of observation for Greece, Turkey, and the Ottoman Empire starting from 1828. The level of analysis is the Greece-Turkey/Ottoman Empire dyad. Using that data set, we then calculate the annual rate of change ([(quantity of increase on t+1)/(value of milexp in t)]*100)) in military expenditures and military expenditures per capita (based on military personnel). These variables permit us to gauge periods of increase in military expenditures for each state. The next step is to differentiate spending increases in subsistence spending from those likely to be part of conscious attempts to increase military capabilities.

To capture this, we mobilized the logic of rivalry. We argue that subsistence-level spending will vary depending on the underlying rivalry conditions, as the variation in the strength of enmity will impact the role that the presence of the other state plays in the minimum required military expenditures each state sets. It is not so much that rivalry intensity drives mutual military buildups as it is that rivalry intensity increases the threshold at which military expenditures are likely to trigger arms race motivations. One of the central effects of rivalry is normalizing a state of military emergency in the minds of decision-makers and the public such that it justifies increased military spending. The stimulus-response logic means that the reaction of the other side at some point will also be normalized. This means that in severe rivalry conditions, what counts as subsistence spending is much higher than under other conditions. This means the threshold at which military expenditures will spark mutual military buildups and potential arms races is also increased.

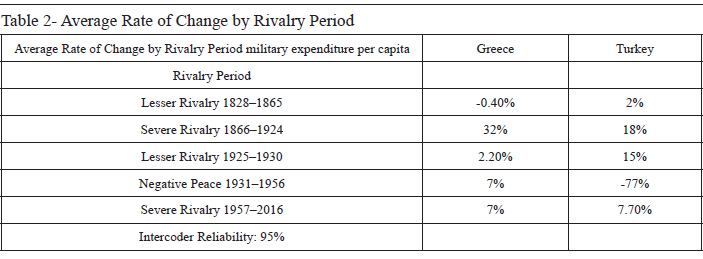

To control for this, we calculate the average rate of change in military expenditures or military expenditures per capita for each rivalry period. We then locate those years within each rivalry period that saw rates of change above the average for the rivalry period. We consider such years to be characterized by military expenditure increases above the norm, and perhaps indicating strategic arming in reaction to the decisions of potential opponents. The average rate of change per rivalry period for Greece and the Ottoman Empire/Turkey can be found in Table 2. The information is encouraging. For all states, the highest average rates of change in military expenditures are during either periods of Severe Rivalry, or during the period straddling the Second World War.

The next step is to locate years of mutual military buildups. Comparing the years characterized by above-average positive rates of change between each dyad member, we build a variable that captures periods of mutual military buildups. We code periods in two versions. One version considers periods of mutual buildups in three-year sets. If the majority of years within each three-year set was characterized by above-average rates of changes for both states in the dyad, then we consider that three-year period to feature a mutual military buildup. This condition lasts until a subsequent three-year set in which the majority of the years is not characterized by above-average rates of increase for both sides. The other version follows the same exact logic, but with five-year period sets. The three- and five-year duration of sets is not chosen on the basis of any theoretical or statistical reason, but to provide a range that should satisfy those who wish to avoid counting as mutual military buildups periods of preparation for war.

Finally, because not all readers will agree with our method in attempting to control for subsistence spending, we also code a version of the mutual military buildups variable that sees a period of mutual military buildup take place when there is an overlap of periods with continuously positive rates of increase “in general” for the two states, even if those rates of increase are not above the average in the rivalry period. “In general” means that most of the overlapping years were characterized by positive rate-of-change scores for both sides and come to an end when three consecutive years are not characterized so. We do not ascribe explanatory power to this variable, but still code it out of ideographic interest.

We are also interested in the temporal association between periods of mutual military buildups and MID onset. We take the years of MID onset from the Correlates of War MID data set.[47] We then code the number of MIDs that began within the mutual military buildup periods in each rivalry period, and then how many began within the five-year period after the termination of a mutual military buildup period. The first variable permits us to see if mutual military buildups and MID onsets are contemporaneous, indicating a potential interactive association. The second variable permits us to gauge if MID onsets are more likely to follow periods of mutual military buildups, indicating a potential causative association.

Here we need to address the issue of multiple rivalries. Both Greece and the Ottoman Empire, and its successor, Turkey, faced other rivalries concurrent to their bilateral ones. In the case of Greece, especially important were rivalries with Bulgaria and Italy, while in the case of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, we have the looming threat of Russia and the USSR. This raised the issue of the effect of multiple rivalries on military expenditures. We argue that this effect is not relevant in this analysis. First, the issue of multiple rivalries becomes relevant at the point of analysis where we are trying to discern the motivation for increased military expenditures. As we have noted, the concept of mutual military buildup is agnostic to motivations. It may very well be that all rivals in a rivalry network increased their military expenditures at the same time, for example, during periods of a general crisis like the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–1885). But that does not negate that those are mutual military buildups for each specific dyad.

Ascertaining which rival the buildups were targeting is the job of qualitative studies that use our catalogue of mutual military buildups in order to explore motivations. Mutual military buildups in which we know there is strategic motivation against a specific rival are arms races. We are not seeking to, and indeed methodologically cannot, ascertain those here. Second, not all platform purchases are equally usable against all opponents. Thus, there is some element in all military buildups that is opponent-specific, though locating what part is for which foe is a task for qualitative research. At this point, all this means is that we are justified in focusing on the role of mutual military buildups between two specific rivals, even if there were also similar conditions at the same time with other rivals. For example, while Greece had a rivalry with both Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire in the 1908–1912 period, the Greek naval expenditures could not be fully used against Bulgaria. The Greek navy’s capital ships were only strategically useful against the Ottoman Empire.

While we do not seek to test any explanatory hypothesis in this analysis, we do approach our descriptive analysis with some expectations derived from existing studies. First, there is the expectation that periods of mutual military buildups should be concentrated in periods of the dyad history that are characterized by Severe or Lesser Rivalry. If mutual military buildups are part of a realpolitik policy program in reaction to threats, we should expect them to take place in periods where conceptions of threat (as encapsulated by rivalry) are more salient. Second, we expect MID onsets to concentrate in periods of mutual military buildups. This comes from the Steps to War literature, in which militarized disputes and mutual military buildups have an interactive role in pushing rival dyads up the Steps to War. Thirdly, we should expect some MIDs to follow periods of mutual military buildups due to the literature on opportunity and willingness, as mutual military buildups permit the competing states to use military options that were not available previously. This expectation does not clash with our second one. The same phenomenon may have a constitutive influence on factors that explain subsequent manifestations.

4.1. Taking stock of the data

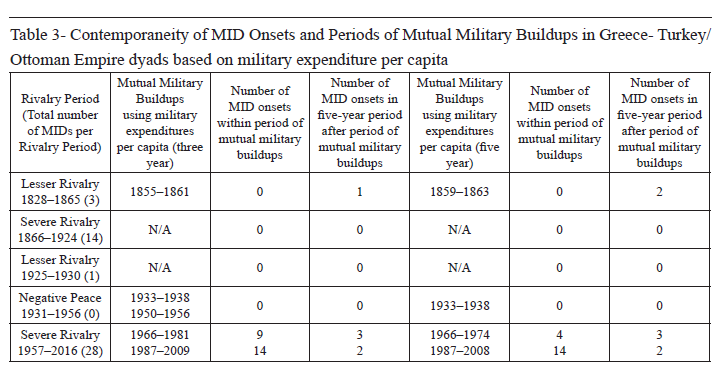

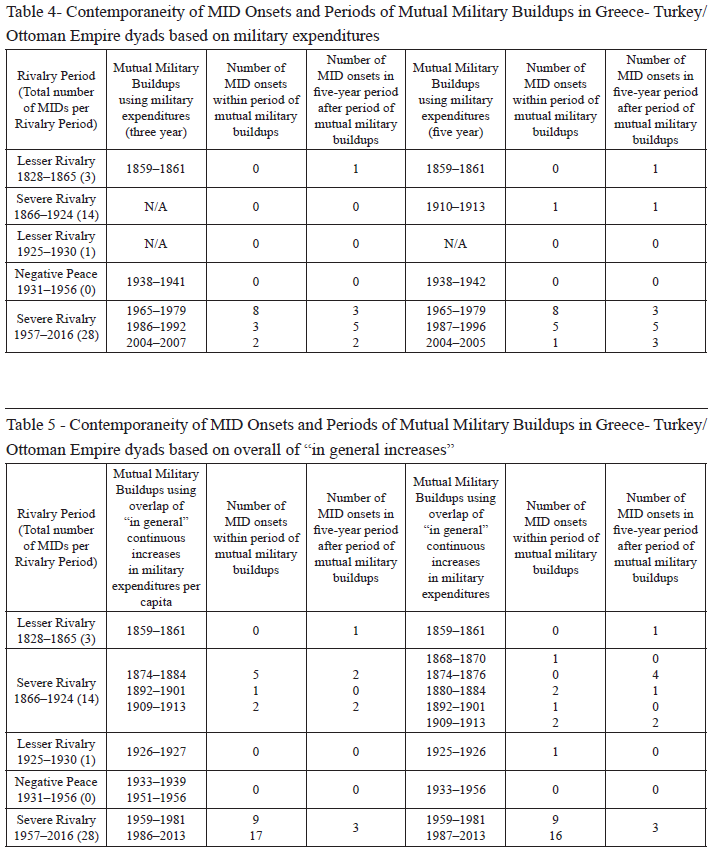

We present the distribution of the data in Tables 3 through 5. Intercoder reliability was 95%. In Table 3, we focus on the contemporaneity of periods of mutual military buildups in each rivalry period, based on military expenditures per capita, with the onset of MIDs. We also explore whether periods of mutual military buildups tend to be followed by MID onsets within five years of their end. In Table 4, we explore the same exact relationships, but with data based on military expenditures. Finally, in Table 5, we do the same, but based on data that includes periods of continuous increases “in general.”

The findings raise interesting questions about our understanding of the role of mutual military buildups, rivalry, and militarized dispute onset, at least for the Greece-Turkey and Greece-Ottoman dyads. In all three tables, the data for the Lesser Rivalry period of 1828–1865 indicate that none of the three MIDs of that period took place during the single period of mutual military buildup. On the other hand, one MID did begin within five years of the end of that mutual military buildup period. This was the inaugural military dispute of the Severe Rivalry period of 1866–1924.

It is also interesting that the mutual military buildup (based on all three versions of the data used) during the 1828–1865 rivalry period began almost right after the 1854 Militarized Dispute. We can hypothesize that the 1854 militarized dispute, and indeed the general Crimean War crisis, led both states to increase military expenditures, which may have played a role in the inauguration of the severe rivalry period beginning with the Cretan Crisis of 1866–1868. In other words, perhaps the mutual military buildup played a role as an additional factor not so much in the eruption of any specific MID after 1865, but of the escalation of the rivalry from Lesser to Severe. From a qualitative point of view, there is no question that what was seen as a humiliation in the 1854 crisis led to serious efforts to strengthen the Greek Navy, which in turn facilitated a more active role for Greece in the Great Cretan Revolt of 1866–1868.

The data on the Severe Rivalry period of 1866–1924 challenges the expectations of the literature on the relationship between mutual military buildups, rivalry, and militarized dispute onset. This is the rivalry period associated with three interstate wars between the Ottoman Empire and Greece (1897, 1912, 1919) and the bulk of MIDs (14 out of 18 MIDs) before the 1930 Ankara Accords that de jure ended a 100-year period of rivalry and conflict. Using the data based on above-average rates of change in military expenditures, there is only one period of a possible mutual military buildup (1910–1913). That one period does see the onset of the 1912 First Balkan War during its duration, and is quickly followed by the 1914 Aegean Islands Crisis. But those are only two of fourteen MIDs that took place in the 1866–1924 period. In other words, the majority of MIDs and wars that erupted between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Greece in the period of Severe Rivalry had no temporal association with mutual military buildups. Indeed, if we focus on above-average rates of change in military expenditures per capita, it is very hard to locate any mutual military buildups.

We can hazard an explanation for this. While the 1866–1924 period was the inflation of the Greece-Ottoman rivalry that had begun in 1828, it was also a period of both states facing multiple rivalries. The creation of Bulgaria posed a foe for both states, while the Ottomans had to also deal with the Russian Empire (a rivalry that would lead to wars in 1828, 1853, 1877, and 1914). Thus, the military expenditures of both states were reacting to potentially diverse external stimuli, which made it less likely that their periods of military buildup would coincide. Furthermore, this was also a period of economic instability for both states, with both Greece and the Ottoman Empire facing economic defaults, many times associated with periods of increased military expenditures. If we combine the multiple external stimuli, as well as the domestic economic instability, we can hint to an answer of why the Severe Rivalry period of the Ottoman-Greece dyad does not see the usual association of mutual military buildups with MID onset.

In Table 5, we present, only for informative purposes, the distribution of data when we relax our stipulation that mutual military buildups can only result from rates of increase in military expenditures (per capita or not) that are above the rivalry period’s average rate of increase. If we do this, then the 1866–1924 period is characterized by three clusters of periods of mutual military buildups, which account for 40–57% of all MID onsets in the period, with 30–50% of MIDs following them within five years of the end of mutual military buildup periods. While more in line with the narrative of rivalry, these findings are based on an ideographic operationalization that has no bearing on explanatory questions.

The de-escalation of the Severe Rivalry period of 1866–1924 after the Greek defeat in the Greek-Turkish War of 1919–1922 into a period of Lesser Rivalry between 1925 and 1930 saw only one MID. It also saw no periods of mutual military buildups if we use data based on above-average values. If we use data increasing “in general,” then there is a short period of mutual military buildups (either 1926–1927 or 1925–1926), which saw the onset of the only MID of the period. This makes sense as the period 1923–1927 saw a period of tension between the two states, both busy rebuilding their militaries, which came to an inflation point with the Pangalos Dictatorship of 1925–1926.[48]

The Ankara Accords of 1930 ushered a period of Negative Peace lasting from 1930 to 1956. No Greece-Turkey MIDs took place in this era, despite the presence of periods of mutual military buildups. In this case, we know those buildups were part of the broader European crisis leading to the Second World War and the early Cold War periods. These dynamics validate the argument that mutual military buildups, and perhaps arms races, outside of a context of rivalry will not be associated with increased tensions.[49] It validates those schools of thought that argue that intentions are more important than capability as correlates of conflict.[50]

The Cyprus issue gave rise to the current Severe Rivalry period in Greece-Turkey relations. Our data largely confirms existing findings on the presence of arms races or reciprocal armament. Depending on the operationalization of military expenditures per capita, 70–80% of MIDs began during periods of mutual military buildups. Five of 28 total MIDs in the period began within five years of the termination of a period of mutual military buildups. Depending on the operationalization of military expenditures, about 50% of MIDs in the period took place during mutual military buildups, and about 40% began within the five-year period after the termination of mutual military buildup periods. The “in general” increase findings are similar. The majority of MIDs in the 1957–2016 Severe Rivalry Period began during periods of mutual military buildups (which cover most of the period). While which of these count as arms races is a question for subsequent qualitative analysis, our findings validate the existing literature that sees elements of arms racing in the post-1957 Greece-Turkey case.

5. Conclusion

In this manuscript we suggested an alternative way to mobilize the concept of interstate rivalry in order to capture periods of mutual military buildups in a dyad. We use the Greece-Turkey and Greece-Ottoman Empire dyads as proof-of-concept examples. We use rivalry intensity, as captured by the Peace Scale in conjunction with military expenditure data from Correlates of War, to capture the variation in subsistence military spending. We argue that this will vary depending on the intensity of rivalry relations in a dyad. Unlike existing studies that use rivalry as proxy for motivations that turn mutual military buildups into arms races, we argue that large-n studies can only locate periods of mutual military buildups and will have to be supplemented by deep qualitative studies of such periods in order to ascertain arms race motivations. Our method presents more nuanced information about periods of mutual military buildups.

Using our method, we locate periods of mutual military buildups in the Greece-Ottoman Empire/Turkey dyads from 1828 to 2014. We focus on both military expenditures and military expenditure per capita (of military personnel). Post-1945, our findings corroborate those of the largely econometric literature on a Greece-Turkey arms race. Our novel findings are about the pre-1945 period, which is understudied in the past literature on mutual military buildups. There, we find that depending on the way we capture military expenditures, more mutual military buildups took place in periods of Lesser Rivalry than Severe Rivalry. The case-specific explanation is that the period of Severe Rivalry in the Greece-Ottoman Empire dyad was also a period of multiple rivalries for both states, meaning multiple opponents acted as external stimuli for spending, making it less likely that the military increases of both states would overlap in time. That said, the more interesting findings arise when we overlay the onset of dyad militarized disputes over periods of mutual military buildups.

In the post-1945 period, most MIDs start in periods of mutual military buildups or in the five-year period after them. In the pre-1945 period, this association is not as strong, though still present. Instead, it seems that the presence of mutual military buildups is a factor that fosters the transition of Lesser Rivalry to Severe Rivalry. We posit that this is a potential role of mutual military buildups that the existing literature had not unearthed. Within Severe Rivalry, the effect of mutual military buildups might be muted due to the increased level of subsistence spending by both sides. What this means is that the rivalry condition makes mundane what before would have been extraordinary, as both states increase their military preparedness. Purchases that in the past might have triggered a crisis for decision-makers are now accepted as the price of rivalry. This means that the threshold for military procurement causing crisis conditions among decision-makers is higher. In a way, Severe Rivalry increases the threshold at which arms race motivations appear by normalizing a state of emergency.

Future research will move along the following paths. First, it is worth applying the methodology to other dyad cases. Second, within the Greece-Turkey and Greece-Ottoman Empire dyad cases, qualitative research can focus on the periods of mutual military buildups in order to discern which ones are arms races and which ones are not. All arms races are mutual military buildups, but not all mutual military buildups are arms races. It is qualitative research that can discern that. Third, the conduct of multivariate analysis to unearth causal patterns between mutual military buildups and MID onset. Fourth, exploring further the potential role of mutual military buildups in the transition of Lesser Rivalry to Severe Rivalry.

Adams, Karen Ruth. “Attack and Conquer? International Anarchy and the Offense-Defense-Deterrence Balance.” International Security 28, no. 3 (2003/04): 45–83.

Aksakal, Mustafa. The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The Ottoman Empire and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Aktar, İsmail, and Abdulkadir Civan. “Is There Any Cointegration between Turkey's And Greece's Military Expenditures?” Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 21 (2008): 241–51.

Antonakis, Νikolaos. Amyntikes Dapanes kai Ethniki Oikonomia: E Periptosi tis Elladas kai ton Choron-Melon tis EOK (Defence Expenditures and National Economy). Athens: Eurokoinotikes Ekdoseis, 1989.

–––. “Military Expenditure and Economic Growth in Greece, 1960-90.” Journal of Peace Research 34, no. 1 (1997): 89–100.

–––. “Oikonomiki Analysi ton Amyntikon Dapanon stin Ellada (Economic Analysis of Defense Expenditures in Greece).” Spoudai 35, no. 3-4 (1985): 205–34.

Avramides, Christos A. “Alternative Models of Defence Expenditures.” Defence and Peace Economics 8, no. 2 (1997): 145–87.

Bae, Jun Sik. “An Empirical Analysis of the Arms Race between South and North Korea.” Defence and Peace Economics 15, no. 4 (2004): 379–92.

Brauer, Jurgen. “Survey and Review of the Defense Economics Literature on Greece and Turkey: What Have We Learned?” Defence and Peace Economics 13, no. 2 (2002): 85–107.

Cashman, Greg. What Causes War? An Introduction to Theories of International Conflict. New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield, 2013.

Choulis, Ioannis, Marius Mehrl, and Kostas Ifantis. “Arms Racing, Military Build-Ups and Dispute Intensity: Evidence from the Greek-Turkish Rivalry, 1985-2020.” Defence and Peace Economics (2021). doi: 10.1080/10242694.2021.1933312.

Colaresi, Michael P., Karen Rasler, and William R. Thompson. Strategic Rivalries in World Politics: Position, Space and Conflict Escalation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Diehl, Paul F. “Arms Races and Escalation: A Closer Look.” Journal of Peace Research 20, no. 3 (1983): 205–12.

Diehl, Paul F., and Mark J. Crescenzi. “Reconfiguring the Arms Race-War Debate.” Journal of Peace Research 35, no. 1 (1998): 111–18.

Diehl, Paul F., and Gary Goertz. War and Peace in International Rivalry. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Diehl, Paul F., Gary Goertz, and Yahve Gallegos. “Peace Data: Concept, Measurement, Patterns, and Research Agenda.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 38, no. 5 (2021): 605–24.

Dritsakis, Nikolaos. “Defense Spending and Economic Growth: An Empirical Investigation for Greece and Turkey.” Journal of Policy Modelling 26, no. 2 (2004): 249–64.

Dunne, Paul J., Eftychia Nikolaidou, and Ron P. Smith. “Arms Race Models and Econometric Applications.” In Arms Trade, Security and Conflict, edited by Paul Levine and Ron Smith, 178–94. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Emen, Gözde. “Turkey’s Relations with Greece in the 1920s: The Pangalos Factor.” Turkish Historical Review 7, no. 1 (2016): 33–57.

Evaghorou, Evaghoras L. “The Economics of Defence of Greece and Turkey: A Contemporary Theoretical Approach for States Rivalry and Arms Race.” In Proceedings of the 10th Annual International Conference on Economics & Security, edited by Eftychia Nikolaidou, 145–71. Thessaloniki: South-East European Research Center, 2006.

Fotakis, Zisis. Greek Naval Strategy and Policy 1910-1919. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Georgiou, George M., Panayotis T. Kapopoulos, and Sophia Lazaretou. “Modelling Greek-Turkish Rivalry: An Empirical Investigation of Defence Spending Dynamics.” Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 2 (1996): 229–39.

Gibler, Douglas M., Toby J. Rider, and Marc L. Hutchison. “Taking Arms against a Sea of Troubles: Conventional Arms Races During Periods of Rivalry.” Journal of Peace Research 42, no. 2 (2005): 131–47.

Glaser, Charles. “The Causes and Consequences of Arms Races.” Annual Review of Political Science 3, no. 1 (2000): 251–76.

Goertz, Gary, Paul F. Diehl, and Alexandru Balas. The Puzzle of Peace: The Evolution of Peace in the International System. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Günlük-Şenesen, Gülay. “An Analysis of the Action-Reaction Behavior in the Defense Expenditures of Turkey and Greece.” Turkish Studies 5, no. 1 (2004): 78–98.

Herrmann, David G. The Arming of Europe and the Making of the First World War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Huntington, Samuel. P. “Arms Races-Prerequisites and Results.” Public Policy 8, no. 1 (1958): 41–86.

Jervis, Robert. “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30, no. 2 (1978): 167–214.

Klapsis, Antonis. “Attempting to Revise the Treaty of Lausanne: Greek Foreign Policy and Italy during the Pangalos Dictatorship, 1925–1926.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 25, no. 2 (2014): 240–59.

Klein, James P., Gary Goertz, and Paul F. Diehl. “The New Rivalry Dataset: Procedures and patterns.” Journal of Peace Research 43, no. 3 (2006): 331–48.

––– . “The Peace Scale: Conceptualizing and Operationalizing Non-Rivalry and Peace.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25, no. 1 (2008): 67–80.

Kollias, Christos G. “Greece and Turkey: The Case Study of an Arms Race from the Greek Perspective.” Spoudai 41, no. 1 (1991): 64–81.

–––. “The Greek-Turkish Conflict and Greek Military Expenditure 1960-92.” Journal of Peace Research 33, no. 2 (1996): 127–228.

Kollias, Christos G., and Stelios Makrydakis. “Is There a Greek-Turkish Arms Race?: Evidence from Cointegration and Causality Tests.” Defense and Peace Economics 8, no. 4 (1997): 355–79.

Kollias, Christos G., and Suzanna-Maria Paleologou. “Is There a Greek-Turkish Arms Race?: Some Further Empirical Results from Causality Tests.” Defence and Peace Economics 13, no. 4 (2002): 321–28.

Leng Russell J., and Robert A. Goodsell. “Behavioral Indicators of War Proneness in Bilateral Conflicts.” In Sage International Yearbook of Foreign Policy Studies Volume 2, edited by Patrick J. McGowan, 191–226. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1974.

Levy, Jack S. “The Offensive/Defensive balance of Military Technology: A Theoretical and Historical Analysis.” International Studies Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1984): 219–38.

Looney, Robert E. “Arms Races in the Middle East: A Test of Causality.” Arms Control 11, no. 2 (1990): 178–90.

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. “Offense-Defense Theory and its Critics.” Security studies 4, no. 4 (1995): 660–91.

Mahnken, Thomas, Joseph Maiolo, and David Stevenson, eds. Arms Races in International Politics: From the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Majeski, Stephen J. “Expectations and Arms Races.” American Journal of Political Science 29, no. 2 (1985): 217–45.

Maiolo, Joseph. Cry Havoc: How the Arms Race Drove the World to War 1931-1941. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Mearsheimer, John J. Conventional Deterrence. Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1983.

––– . The Tragedy of Great Power politics. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Michail, Mary and Nicholas Papasyriopoulos. “Investigation of the Greek-Turkish Military Spending Relation.” International Advances in Economic Research 18, no. 3 (2012): 259–70.

Mitchell, David F., and Jeffrey Pickering. “Arms Buildups and the Use of Military Force.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics 27. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Mitchell, David F., and Jeffrey Pickering. “Arms Build-Ups and the Use of Military Force.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Foreign Policy Analysis, edited by Cameron G. Thies, 61–71. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Most, Benjamin A., and Harvey Starr. Inquiry, Logic and International Politics. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989.

Organski, Abramo F. K. and Jacek Kugler. The War Ledger. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Palmer, Glenn, Vito D’Orazio, Michael Kenwick, and Matthew Lane. “The MID4 Data Set, 2002-2010.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 32, no. 2 (2015): 222–42.

Richardson, Lewis Fry. Arms and Insecurity: A Mathematical Study of the Causes and Origins of War. Pittsburgh, PA: Boxwood, 1960.

Rider, Toby J., Michael G. Findley, and Paul F. Diehl. “Just Part of the Game? Arms Races, Rivalry, and War.” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 1 (2011): 85–100.

Rudkevich, Gennady, Konstantinos Travlos, and Paul F. Diehl. “Terminated or Just Interrupted? How the End of a Rivalry Plants the Seeds for Future Conflict.” Social Science Quarterly 94, no. 1 (2013): 158–74.

Şahin, Hasan and Onur Özsoy. “Arms Race between Greece and Turkey: A Markov Switching Approach.” Defence and Peace Economics 19, no. 3 (2008): 209–16.

Sample, Susan G. “Arms Races and Dispute Escalation: Resolving the Debate.” Journal of Peace Research 34, no. 1 (1997): 7–22.

–––. “Furthering the Investigation into the Effects of Arms Buildups.” Journal of Peace Research 35, no. 1 (1998): 122–26.

––– . “Military Buildups, War, and Realpolitik: A Multivariate Model.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 42, no. 2 (1998): 156–75.

––– . “Military Buildups: Arming and War.” In What do we Know about War 1st Edition, edited by John A. Vasquez, 167–96. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000.

––– . “The Outcomes of Military Buildups: Minor States vs. Major Powers.” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 6 (2002): 669–691.

Senese, Paul D., and John A. Vasquez. The Steps to War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Sert, Deniz Ş., and Konstantinos Travlos. “Making a Case over Greco-Turkish Rivalry: Major Power Linkages and Rivalry Strength.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi-Journal of International Relations 15, no. 59 (2018): 105–27.

Singer, David J., Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965.” In Peace, War, and Numbers, edited by Bruce Russett, 19–48. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972.

Slayton, Rebecca. “What is the Cyber Offense-Defense Balance? Conceptions, causes, and assessment.” International Security 41, no. 3 (2016/17): 72–109.

Smith, Ron P., Paul J. Dunne, and Eftychia Nikolaidou. “The Econometrics of Arms Races.” Defence and Peace Economics 11, no. 1 (2000): 31–43.

Stevenson, David. Armaments and the Coming of War: Europe, 1904-1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Thompson, William R. and David R. Dreyer, eds. Handbook of International Rivalries. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2011.

Valeriano, Brandon. “The Steps to Rivalry: Power Politics and Rivalry Formation.” PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 2003.

Vasquez, John A. “What Do We Know about War?” In What do we Know about War, 2nd Edition, edited by John A. Vasquez, 301–30. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012.

Walt, Stephen M. The Origins of Alliances. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987.

Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Werner, Suzanne and Jacek Kugler. “Power Transitions and Military Buildups: Resolving the Relationship between Arms Buildups and War.” In Parity and War: Evaluations and Extensions of The War Ledge, edited by Jacek Kugler and Douglas Lemke, 187–207. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Yildirim, Jülide and Nadir Öcal. “Arms Race and Economic Growth: The Case of India and Pakistan.” Defence and Peace Economics 17, no. 1 (2006): 37–45.

Zinnes, Dina A. Research in International Relations: A Perspective and a Critical Perspective. New York, NY: Free Press, 1976.