İrem Karamık

Hacettepe University

Erman Ermihan

Kadir Has University

The International Relations (IR) discipline is ascendant because of the theoretical and methodological divisions and controversies within. As it is mostly placed in the Non-Western IR category, Turkish IR is an interesting case in that it reveals the temporal changes of theoretical debates in IR and their local resonance from the purview of a geography that is jammed between the West and the rest. For this reason, this paper examines the literature on the Turkish School of IR (if there is any) and draws some conclusions regarding its current state. This research first utilizes the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) surveys conducted by the International Relations Council of Turkey (IRCT) between 2007 and 2018. More extensively, the top 20 journals categorized under Google Scholar’s “Diplomacy and International Relations” list are coded based on their titles containing “Turkey.” Articles from the 1922–2021 period are then analyzed considering their authors, abstracts, and keywords. From this analysis, the study finds that studies focusing on Turkey have improved over the years, although there is a need for more theoretical and methodological advancements. As a “peripheral” country in IR, Turkey is still a subject of study by the “center” countries.

In tandem with the developments and changes in global politics, IR has also been going through significant theoretical and methodological phases. During this transition, IR scholars have been discussing ways of transcending the Western dominance in the discipline. In doing so, recent studies have put forward various propositions under Post-Western IR, Non-Western IR, Global IR, and the like.[i] However, scant attention has been given to the intricacies between global and local developments. To this end, Turkey represents an interesting case to investigate the connection between local and regional developments in IR. For this reason, this article will attempt to unravel Turkey’s position in these discussions by studying articles focusing on Turkey in the top twenty journals that appear in the Google Scholar database. Thus, this article will uncover the relationship between Turkish IR and Global IR, which would enable a better understanding of the discipline’s path forward.

Along with the developments of critical perspectives towards IR, the increasing focus on non-Western, post-Western, and Global IR reflects a need for progressive change in the discipline. Subsequently, such new perspectives pave the way for new discussions on IR’s different localities within the global. Those discussions highlight Turkey as an interesting case study given that the country represents different theoretical and methodological variations of IR, especially over the last two decades. Thus, focusing on and studying countries such as Turkey will enable researchers to see the different contributions to IR.

We begin with a brief review of the literature to study and locate Turkish IR in relation to the broader discipline and within the burgeoning Global and Non-Western IR discussions. We follow this up with a brief historical reflection on the development of the IR discipline in Turkey. This will help to contextualize our empirical study of Turkish IR, which we will discuss in the succeeding section. Along with the results of the analysis, the final sections present the main conclusions of this study while offering several suggestions for further research.

The development of International Relations (IR) as a discipline in Turkey could be traced back to the Tanzimat period, during which civil servants were trained under public administration programs, leading to the creation of Mülkiye in 1859.[ii] Such a historical account takes the first IR department, founded in 1919 at Aberystwyth, further back in history by highlighting different localities within the discipline. Thus, by focusing on the contributions of other localities such as Turkey, this study aims at locating Turkey in the broader discussions on center-periphery in IR. Back then at Mülkiye, the focus was mostly on “hukuk-ı düvel”/International Law. In the following period, there were significant changes in the discipline. For instance, there were idealistic attempts to move IR beyond simply the study of states.[iii] With the rise of the influence of the United States over Mülkiye, however, IR became a separate discipline in the Faculty of Political Science in the 1960s.

Until the 1980s, IR in Turkey was studied in close relation to Turkish foreign policy, international relations, and international law. After the 1980 coup, many IR faculty members were fired and imprisoned, causing the discipline to loom up activity-wise. Entering the 1990s, the discipline in Turkey witnessed a period of rich theoretical and methodological research, and an increase in the scholars who conducted research on IR. In other words, more studies with theoretically and methodologically rich and sophisticated research started to be produced. As of August 2021, according to Yükseköğretim Bilgi Yönetim Sistemi (Higher Education Information Management System) of the Council of Higher Education (YÖK) in Turkey, there are currently a total of 1,602 scholars in the departments of International Relations.[iv]

Currently, scholars of IR in Turkey pose certain theoretical, methodological, and structural criticisms of the current state of IR in Turkey. One such criticism is about getting lost in big theoretical debates.[v] Köstem argues that knowledge of relevant facts is crucial to building theoretical arguments around them, urging the need for familiarity with non-Western political theory as well as Western political theory. It is further argued that although the recent emphasis on constructivism and critical theories in Turkish IR scholarship is promising, there is a considerable tendency to disregard theoretical perspectives from the mainstream Western IR.[vi] In other words, there is a lack of theoretical debate among scholars who are militating against field consolidation.[vii] In addition, it is underlined that there are hardly any theoretical contributions to the grand theories of IR from Turkish IR scholars. This is likely aggravated by a systemic problem of low support for those scholars who aim to bring a new breath to the field.[viii]

One of the recent criticisms drawn to the Turkish School of IR is the lack of quantitative research. Aydınlı and Biltekin argue that the Turkish School of IR has a fragmented nature, and that one way of overcoming such fragmentation is to produce more research in the quantitative field.[ix] Moreover, a recent study observing 7,792 articles in the top twelve journals in the field dating between 1980 and 2014 has shown that quantitative research is more likely to get published, creating fault lines and divides within the IR and Political Science disciplines.[x] The analysis suggests that the discipline now faces top journals following a one-method-only tradition: the researches in the field are either only quantitative or only qualitative. For scholars from the Turkish School of IR, publishing more quantitative studies might strengthen the presence of the scholars on the one hand, while contributing to the existing divides in the discipline on the other. Another recent criticism posed to the Turkish School of IR is that the regional studies produced in Turkey on the Middle East and Europe mostly remain as case studies on Turkey and receive citations largely from Turkey. Thus, the study argues that the knowledge produced on the IR discipline in Turkey stays within Turkey and cannot reach the rest of the world.[xi]

Rather differently, Bilgin and Tanrısever develop another argument about the Turkish School of IR and explain it in its dualities.[xii] For instance, while scholars of Turkish IR choose different topics for their Ph.D. research, their international publications remain limited to the scope of Turkish foreign policy. Such duality is an example that could be sought in the “disciplinary politics of IR” and the “dynamics of international politics.”[xiii] In the disciplinary politics of IR, scholars such as those from Turkey are expected to apply the universal theories to their areas and collect data as if they are “native informants.”[xiv] The dynamics of international politics, moreover, aim at explaining Turkey’s Western state identity in scholarly works. With the 1980s’ liberalization attempts, the authors argue that IR in Turkey became a separate discipline, decreasing its interdisciplinary nature and reducing interest in homegrown theory-building. In addition, the lack of internal debates among Turkish scholars of IR and the debates revolving around Turkey’s national interest in becoming a European Union (EU) member contributed to the existing dualities of the Turkish School of IR.

Turkey’s position in the Western–Non-Western IR debate was observed from a variety of perspectives in several studies. Mentioning this debate on Western–Non-Western IR also requires references to the developing Global South arguments, which might be tied to the Turkish School of IR as well. Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan discuss this issue in two studies published in the ten years between 2007[xv] and 2017.[xvi] They argue that some reasons for the lack of a non-Western IR theory could be found in the hegemony of Western IR, asymmetry in scholarly resources, and the like.[xvii] When they revisit their work ten years later, they find out that there is an increasing interest in theory in Asian IR. Such interest in theory is argued to be challenging Western IR. Moreover, there is hope in non-Western IR that scholars relying on middle-range theories use more inductive approaches. Such scholars also benefit from classical traditions and civilizations when challenging Western IR, such as those coming from the “Turkish-Islamic world.”[xviii] However, the authors suggest that developing a regional school of IR is unlikely.

Having examined some of the recent debates about the status of IR, Turkey, and Turkish IR within the wider IR discipline, it is appropriate to observe how the field of IR developed in Turkey. Outlining the milestones during the development of Turkish IR would pave the way for a better understanding of this paper’s analysis and its empirical results. Thus, the next section briefly focuses on how the discipline of IR was shaped in academia in Turkey.

As stated above, the Turkish School of IR coalesced under Mülkiye, which was established to provide education on diplomatic history and international law. Mülkiye was primarily an “elitemaking institution,” which aimed at producing diplomats and cadres for the political elite in Turkey.[xix] Until the 1980s, it could be argued that the discipline was limited to the academic engineering made under the roof of Mülkiye, which was highly influenced by the national social and political atmosphere. Imagining a Western-influenced IR education in Turkey was, before all, an identity-building tool on the path to Turkey’s Westernization attempts.[xx] Moreover, because the main purpose was to train future diplomats, theory education was not a primary concern. However, with the liberalization attempts in the 1980s, students from various backgrounds found the opportunity to acquire the relevant skills to contribute to the discipline.[xxi]

In the aftermath of the 1980 coup, a significant number of faculty members lost their jobs, and IR was placed under the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences in several universities. After the coup, it is argued that YÖK was formed to work in parallel with the aims of the coup and become one of the key actors who would enable Turkey to transition to a neoliberal economy.[xxii] Meanwhile, IR education in Turkey had been degraded so much that in 1986, the number of IR scholars in Turkey was only 13.[xxiii] Gradually, as the number of scholars in the IR discipline in Turkey increased, they were sent to Anglo-Saxon universities to learn the core theoretical debates and apply them to their studies in Turkey as the emphasis on history was sidelined.

After the end of the Cold War, the transition from a bipolar to a unipolar international system had an impact on the IR discipline as well. The discipline started to discuss issues such as globalization, economic dependency, organized crime, global terrorism, and environmental degradation.[xxiv] The increasing number of non-state actors also contributed to uncertainty both in the international structure and the IR discipline. Moreover, as Aydın further argues, at the beginning of the 2000s, the Turkish School of IR witnessed an increase in the methodological debates and studies beyond Turkey. Concomitantly, novel global developments and extant disciplinary trends began to gain traction. Scholars began to question the scientific integrity of the discipline that is increasingly marked by a division of labor in which Anglo-Saxon scholars engaged in the prestigious task of theory-building. At the same time, the application of those theories was left to scholars in non-Western IR.[xxv]

To understand the recent interactions between the Turkish School of IR and mainstream IR in the last decade, the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) survey conducted by the International Relations Council of Turkey (IRCT) surveys are indispensable. The first two studies in 2007 and 2009 were directly conducted by IRCT. The three studies in 2011, 2014, and 2018 were conducted in cooperation with the Institute for the Theory and Practice of International Relations at the College of William and Mary. In the 2007 research conducted only with Turkish scholars, there are some questions regarding IR theories.

In the 1990s, the scholars who participated in the survey indicated that realism was given the most emphasis, followed by constructivism and liberalism. When asked about the most dominant theoretical approach in the discipline, the respondents indicated neorealism by 47%, followed by neoliberalism (27%) and constructivism (24%). In the 2009 survey, the respondents stated that they use a blend of different theoretical approaches in their courses or when they try to explain the incidents in IR. When they are asked about the current theoretical approaches in the IR discipline, they state the mainstream approaches more and weigh the critical theories less. For instance, 66.3% of the respondents state that the Marxist approach is used between 1–20%, while 45.2% think that the liberal/neo-liberal approach is used between 21–40%.

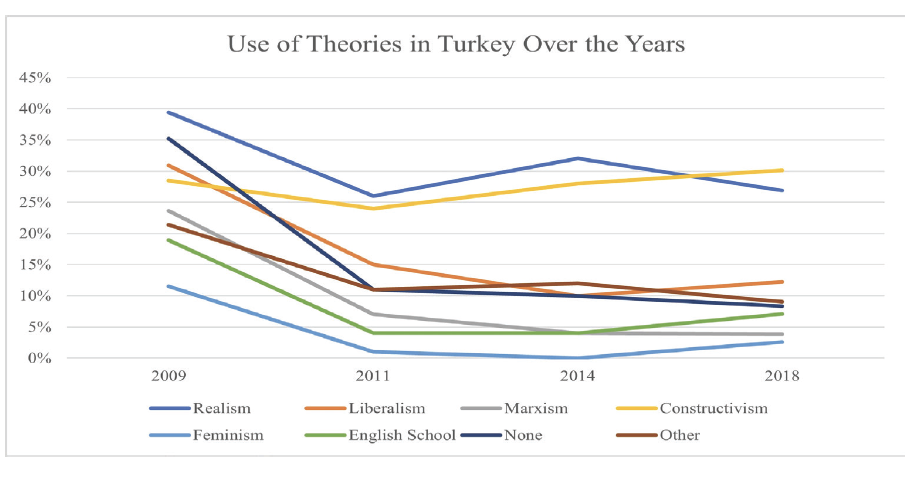

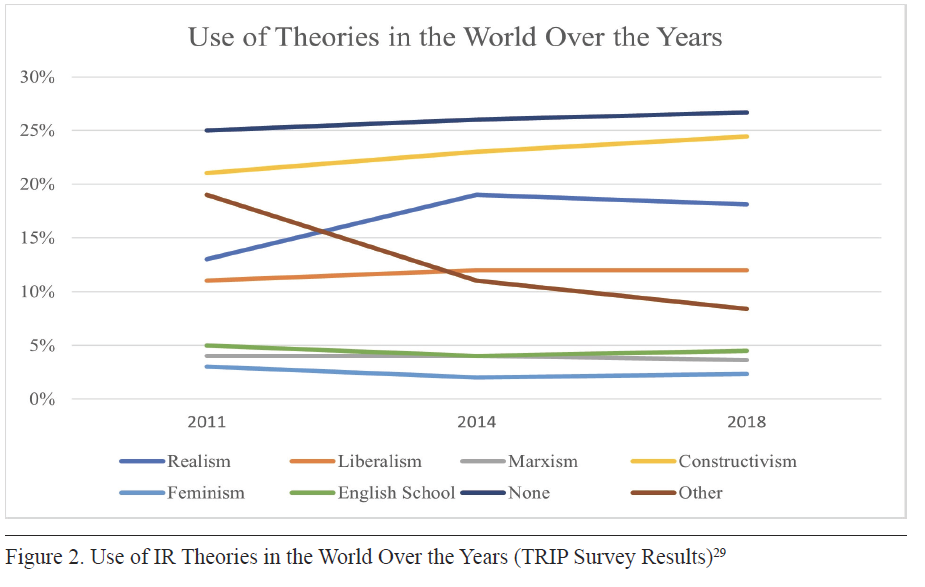

In the 2011 TRIP survey, the results offer more nuanced conclusions about the Turkish School of IR. In 20 countries involved in the research, constructivism is seen to be the most common theoretical approach. On the other hand, the respondents who do not use any theoretical approach have the same ratio with constructivism. In Turkey, realism is the most common approach, followed by constructivism and liberalism. Compared to this study, the 2014 TRIP survey[xxvi] reveals that IR scholars around around the world use constructivism the most. However, 26% of those scholars state that they use no theoretical approaches. In Turkey, constructivism is the second most common theoretical approach after realism. The percentage of Turkish scholars that do not use a theoretical approach in their research is much lower than the world average (10%). This percentage decreases more in the 2018 TRIP survey (8.3%), while the world percentage increases slightly (26.7%).[xxvii] Furthermore, constructivism is placed at the top in this survey both by international and Turkish scholars. The Turkish scholars who use constructivism and realism are higher than the world average by 5.7% and 8.8%, respectively (Figure 1; Figure 2).[xxviii]

Figure 1. Use of IR Theories in Turkey Over the Years (TRIP Survey Results)

Figure 2. Use of IR Theories in the World Over the Years (TRIP Survey Results)[xxix]

The five TRIP surveys mentioned above are peculiar and highly beneficial both for the Turkish School of IR and global IR because they reveal decades-long tendencies and shifts in the discipline. As could be observed, the Turkish School of IR is following the global theoretical trend, which gives primacy to the constructivist approach. What is significant is the divergence of the Turkish School of IR from global IR in terms of the absence of mid-range and grand theory use. While a considerable number of global IR scholars persist in not using any theoretical approaches, the Turkish School of IR generally benefits from them. Coined due to the criticisms of the lack of theoretical contributions by the Turkish School of IR, this could create a dilemma that could prevent the Turkish School from reaching its potential. Such critical approaches are presented in the next section in more detail.

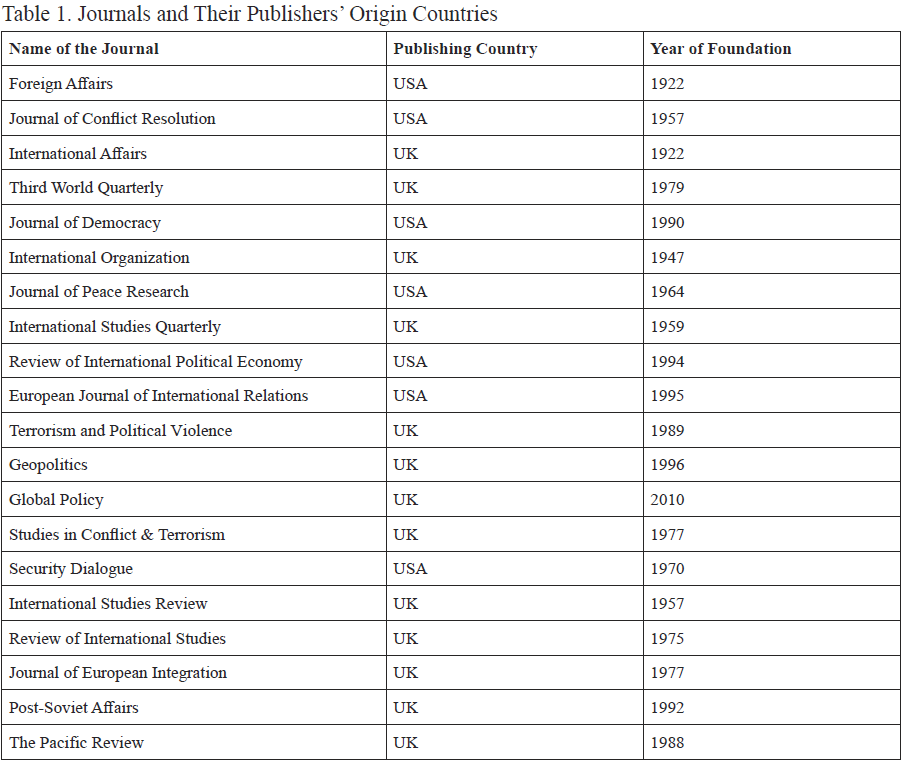

Based on the aforementioned literature, this study offers an analysis of Turkish IR’s global position. To this end, this paper utilizes Google Scholar’s “Diplomacy and International Relations” list that showcases twenty of the top journals in the field. By analyzing the articles written on Turkey in these journals (Table 1), this article aims to locate both how Turkey is studied in the international journals (if they are international) and how many of the studies on Turkey are of Turkish or international origin. In addition, the study also aims to analyze the scholars’ institutional backgrounds to see whether scholars publishing on Turkey in the mentioned journals come from and/or work at Turkish or international universities.

To avoid data loss, we scrutinized all twenty journals’ websites and searched for the keyword “Turkey” in all relevant fields since their foundation dates, making the database span between 1922 and 2021. In 417 articles that are gathered through the analysis of the journals listed in the Google Scholar, the search, titles, abstracts, and keywords are accumulated based on whether they contain “Turkey” and words related to “Turkey,” such as “Turks” or “Turkish.” Then, the relevant articles are classified based on their respective authors, their institutional affiliations, and their regional location at the time of publication. Moreover, the articles are classified by their titles, keywords, and their stated use of any theory, methodology, and case topic. We did not introduce any temporal limitations to these searches so as to find all scholarly articles in top IR journals related to Turkey because as demonstrated in Table 1, there is a large gap in time between the foundations of the 20 journals included in the dataset. As Turkish IR academia started to show more progress during the 1980s and 1990s, and as the study of Turkey became more widespread with the effects of neo-liberalization and globalization, the dataset is aimed to be as inclusive as possible to avoid skewing the data toward only contemporary articles and, instead, reveal the current state of IR studies on Turkey.

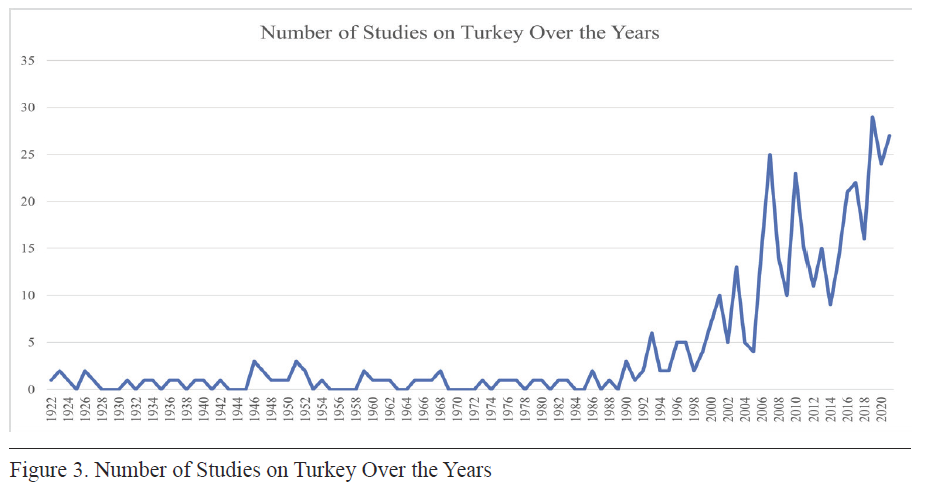

Our coding of a total of 417 articles offers seminal conclusions about the state of the discipline and Turkey’s position within. First of all, while the publications on Turkey had a steady rhythm until the 1990s, they enjoyed a dramatic upsurge in popularity in the following years and decades. Moreover, as can be seen in the figure, the number of studies on Turkey has been increasing, especially since the early 2000s (Figure 3). This period coincides with Turkey's new domestic and foreign policy with the election of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) as it had new regional ambitions, willingness to pursue the European Union (EU) candidacy process, and the like.

Figure 3. Number of Studies on Turkey Over the Years

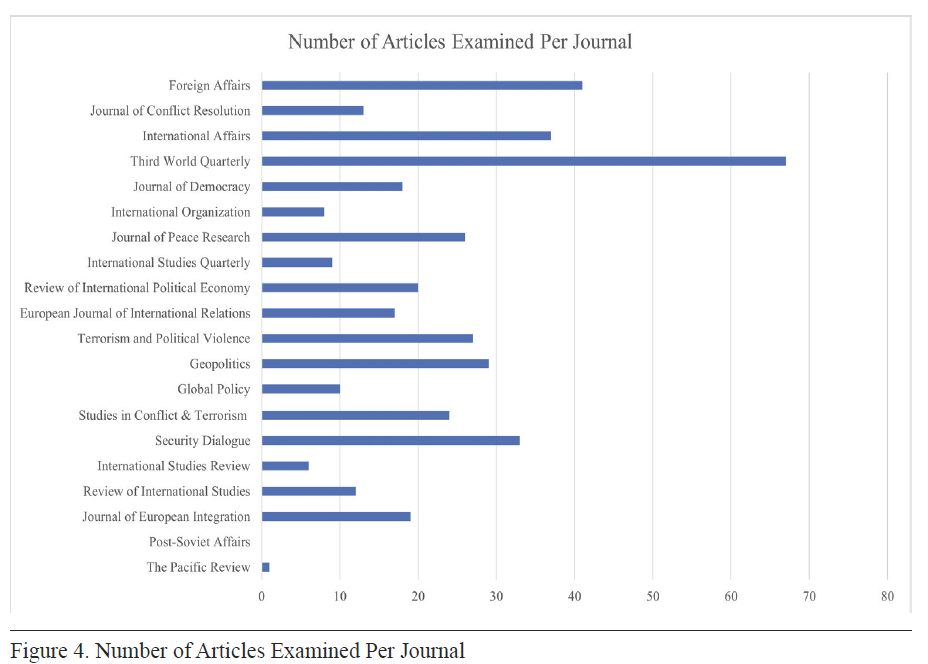

Figure 4. Number of Articles Examined Per Journal

The articles written on Turkey are hosted by distinct journals of differing density. As can be observed in Figure 4, most articles on Turkey found a home in Third World Quarterly, Foreign Affairs, and International Affairs. This could be a result of the journals’ scopes and aims; however, being commemorated as a matter of the Third World comes into conflict with Turkey and Turkish IR’s aim of Westernization, or First Worldization, in this context. It is worth noting that these journals are in the top five list of Google Metrics. Thus, it could be argued that Turkey receives scholarly attention in high-ranking journals based on their impact factors.

Table 1. Journals and Their Publishers’ Origin Countries

Table 1 shows that out of the 20 journals examined in this research, 13 journals are published in the UK, whereas seven are published in the USA. This is also an issue in the ongoing post-Western IR debates as well. As problematic as it is, there is a dominance of US- and UK-based journals in academia. In the last few years, publishing in top journals has also become challenging, as could be seen by their acceptance rates.[xxx] However, academic visibility and performance criteria are still heavily based on publishing in top journals, having high impact factors, and citation scores, which are still considerably low in Turkish academia.[xxxi] Moreover, the very database used in this study is Google Scholar’s journal metrics, which are impacted by top publishers and indexes rooted in the Anglo-American academic tradition that also determines the authors’ citation scores and academic rankings. In addition, many journals host a tradition of theirs in terms of their specific issue areas, theoretical focuses, and methodological standards, which engraves Third Worlders in their current status and prevents them from developing a globally visible tradition of their own. Nevertheless, this very issue could be a matter of another article that might reveal the gatekeeping mechanisms in the academic publishing industry.

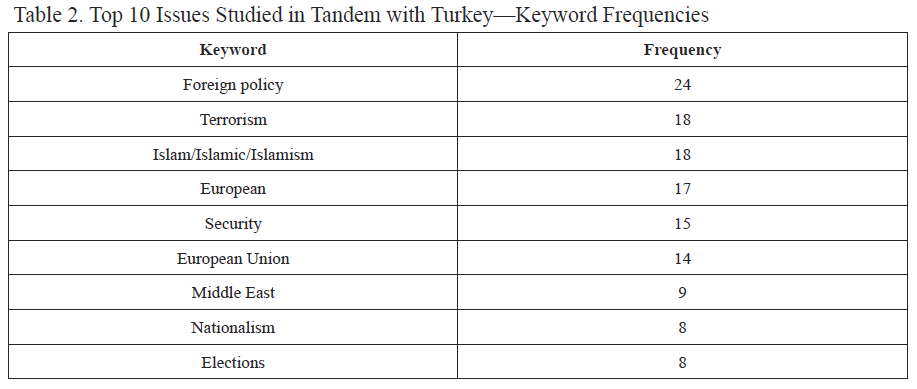

Table 2. Top 10 Issues Studied in Tandem with Turkey—Keyword Frequencies

Based on the articles analyzed for this research, it is also vital to observe the issues and/or cases studied in tandem with Turkey. This is done by collecting the keywords of the articles and creating a frequency list. As shown in Table 2, the issues of the European Union, terrorism, identity politics, religion, conflict, and democracy/elections are studied the most. It is also worth noting that as derived from the results of this study, many articles do not indicate any keywords and hence give a blurry idea of what the matter at hand is. The results of “foreign policy” and the geopolitical keywords such as “European,” “European Union,” and “Middle East” follow Turkey’s foreign policy footsteps, and these results are not surprising to the authors, who expected as much. What is striking is that studies about Turkey are often associated with “terrorism,” “Islam/Islamism/Islamic,” and “security.” For studies on security, conflict, and terrorism, Turkey constitutes a significant case study due to its ongoing counterterrorism measures and security agenda that encapsulates the Syrian conflict. Following the global counterterrorism context that occurred after 9/11 and the War on Terror approach, Turkey, under the AKP government, aimed at coining Islam and democracy, especially through its efforts in the “Alliance of Civilizations” initiative, which also paved the way for constructivist ideational analyses on Turkey’s possible soft power attempts.

Furthermore, four of the selected journals directly subjectify security, terrorism, and conflict. Hence, these keywords are emphasized in studies on Turkey. In tandem with the global post-9/11 structure, Turkey’s domestic conflict with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which led to a short interval of peace negotiations especially between 2009 and 2015, inspired several studies on conflict resolution, peace studies, and terrorism. Moreover, after 2011, with the start of the Syrian Civil War and the creation of the Islamic State (ISIL/ISIS), Turkey’s conflict with other organizations, called the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the People’s Defense Units (YPG), came into question in several studies.

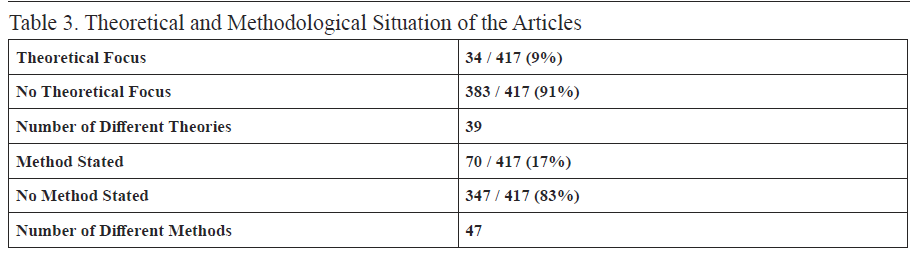

Another aspect of the articles is their interaction with theories and methods. As a serious limitation of the study, of the articles that focus on Turkey, 383 out of 417 articles (91%) do not express a theoretical focus, as stated in their abstracts.[xxxii] The articles that have a theoretical focus, on the other hand, are diverse in their use of theories. In addition, some of the articles utilize more than one theory. When the theories are analyzed closely, the securitization theory and the constructivist theories are used three times each, making them the most used theories in the articles. Including the different varieties of constructivism, 39 different theories are utilized in the articles. Such results demonstrate that the articles that study Turkey refrain from using and/or specifically indicating their theoretical approaches. This finding corroborates existing studies by revealing that Turkish IR is indeed trapped in the mainstream theoretical approaches, and there is no effort for a local, original theoretical contribution in sight.[xxxiii]

The articles’ use of various methodologies also highlights significant issues regarding studies on Turkey. Of the articles that focus on Turkey, 347 out of 417 articles (83%) do not make any references to methods or methodologies in their abstracts. This percentage is slightly lower than that of the use of theories. As in the case of theories, some articles employed more than one methodology. Moreover, compared to theories, articles that focus on Turkey showcase a more diverse set of methodologies. In those articles, 47 different methods are utilized when the different variants of the same method are also included. In such methods, interviews and surveys are the most common (12 times and 10 times, respectively), followed by discourse analysis (5 times). Although the most frequently employed methods are qualitative, quantitative methods, regression analysis, synthetic control method, and the like are also used. Overall, similar to the case for the use of theories, there is still room for progress for the studies focusing on Turkey in terms of their utilization of methods (Table 3).

Table 3. Theoretical and Methodological Situation of the Articles

As discussed by Çiğdem Kentmen-Çin and Ebru Canan-Sokullu[xxxiv] on the data gathered in 2014, 67 out of 101 Turkish universities who teach International Relations accommodate at least one quantitative methods class in their curriculum. However, surveys conducted in the same study display that students associate IR with qualitative methods and shy away from quantitative methodology. In a similar vein, Göçer and Şenyuva’s study[xxxv] on the research of migration in Turkey reveals that unlike dominant migration studies, Turkish IR studies approach the migration issue from the context of security; however, method-wise, they are restrained compared to the rest of the world. Göçer and Şenyuva clearly underline that the methodological shortage salient in Turkish IR is also evident in migration research, and, in many cases, the tools used in quantitative research, such as interviews and surveys, are not executed correctly. Şatana[xxxvi] reassures us that despite some methods and theories being preferred, in Turkish IR, no approach will expire, and every method and theory will find its followers. She also highlights Turkish IR’s capability of adopting itself to the emerging approaches in the field. However, it is also open for discussion since the field is impacted widely by Western approaches, and local studies hardly find a home within IR.

Besides the theoretical and methodological focus of the articles, there are also other critical points to highlight. First of all, there is a lack of interdisciplinary work regarding the case of Turkey. Although there needs to be more rigorous work on this point, it could be argued that an overwhelming majority of the articles is rooted in the discipline of IR. It should also be underlined that the articles published on Turkey in these journals are not confined to the ones produced only by the scholars coming from the discipline of IR. Although it is possible to argue that these journals constitute a common ground for IR to become interdisciplinary both theoretically and methodologically, one of the jarring omissions is the lack of interdisciplinary studies on Turkey in the coded journals. Similarly, international law remains on the margins of studies on Turkey, although it is an often-debated field regarding Turkey’s disputes with terrorist organizations and maritime borders.

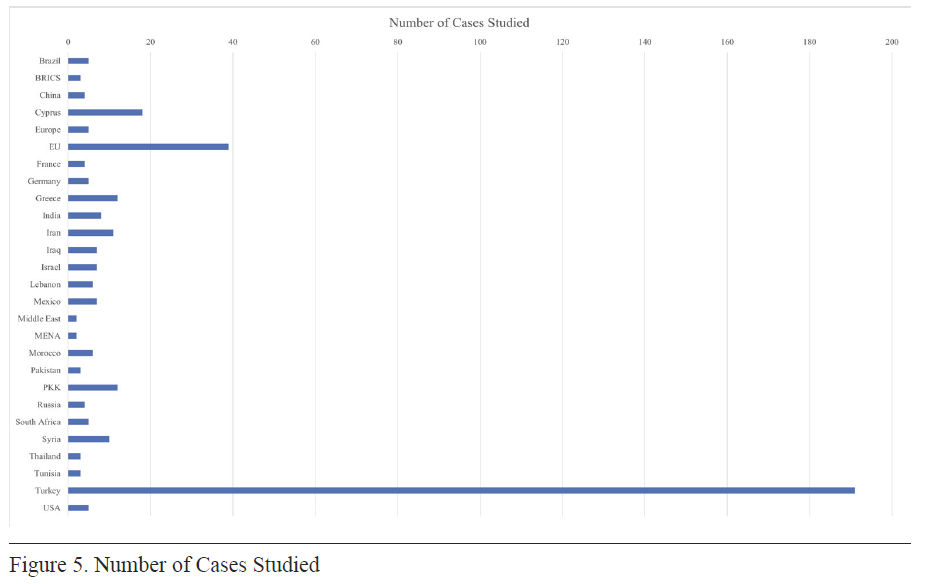

Figure 5. Number of Cases Studied

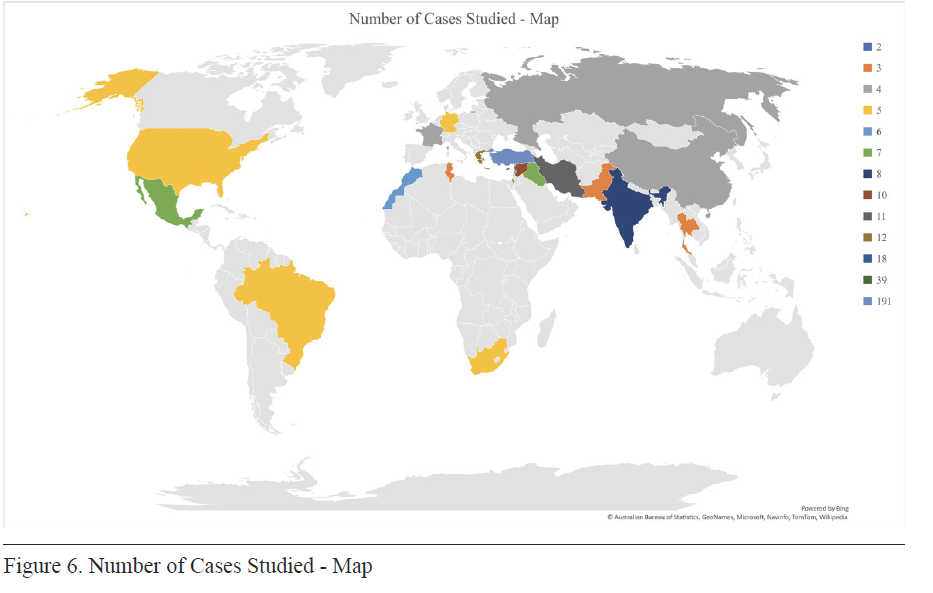

When we correlate Turkey with specific regions and case studies, the European Union emerges as the most popular topic that appears in Turkey-related articles (Figure 5). It should also be noted that several articles dealt with more than one case. In order to discern broader trends, Figure 4 below does not contain all the cases found in the studies because their number of uses is less than three. Geographically, most of the cases focused on are Turkey’s neighbors, especially in the Middle East and Mediterranean (Figure 6), or the prevalent issue areas that Turkey is known for: the Kurdish issue, Cyprus conflict, or Syrian migratory flows of 2015. However, though the Cyprus issue has become prevalent again in recent years, there are very few articles that focus on it, along with the case of Turkey. More importantly, there is a gap in the literature that focuses on Turkey, which does not take the Global South much into account. In addition, China and Russia also stay in the margins of the studies that focus on Turkey.

Figure 6. Number of Cases Studied - Map

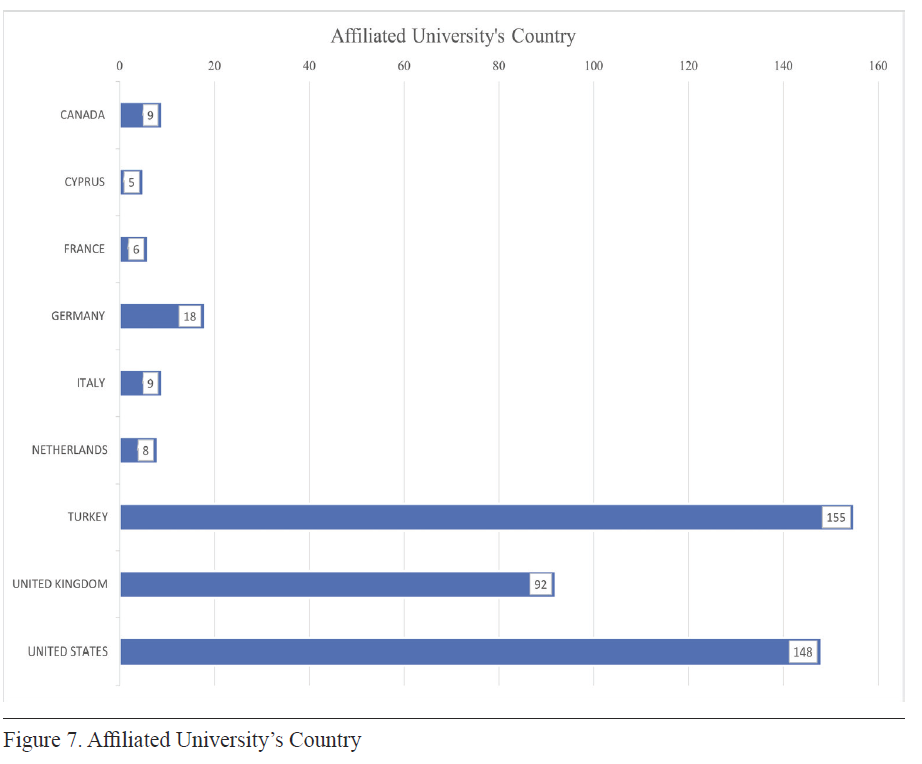

Figure 7. Affiliated University’s Country

Another dimension of the analysis focuses on the authors’ affiliated universities. Observing the scholars’ affiliated universities reveals their schools of employment at the time of submitting the coded articles. The universities at which the scholars are employed may reveal their theoretical and methodological backgrounds and preferences. After coding the authors’ universities as they are indicated in their articles at the date of publication, it is possible to argue that there is Western domination, as was the case in the observed journals in this article (Figure 7). Conversely, the scholars who contribute to Turkish IR and are employed in the USA are almost equal to those in Turkish universities, as seen in Figure 7. Contrary to our hypothesis, Cyprus hosts the fewest scholars that publish in Turkey. Moreover, as indicated in Figure 6, Germany has a mix of scholars that have Turkish affiliations (such as heritage), which are reflected in the results. All in all, these very factors should be studied further to compare the differences between non-Western and Western training in IR.

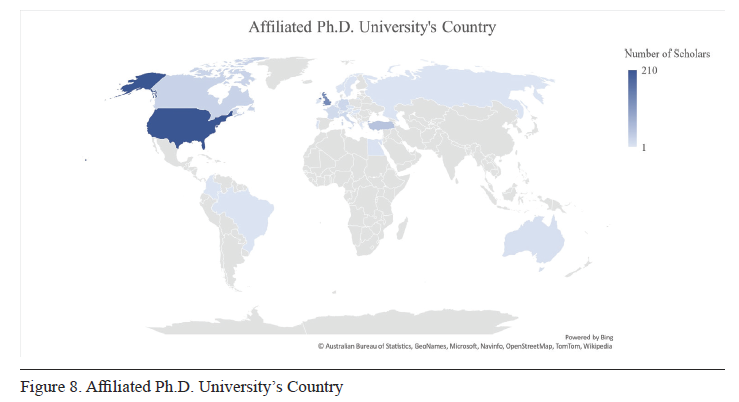

Figure 8. Affiliated Ph.D. University’s Country

The study's final dimension highlights the universities where authors received their Ph.D. degrees. Using official open-source information on the authors, the universities and countries are coded based on the number of frequencies. As a methodological note, there are minor double-coding cases, i.e., if an author published multiple articles. However, it does not affect the overall finding of this particular data. As can be observed in Figure 8, the authors received their Ph.D.s predominantly from Anglo-Saxon universities in the USA (210) and the UK (128). Such a finding is similar to the one in Figure 6, revealing the Anglo-Saxon domination in authors’ affiliated universities. After the USA and UK, Turkey (46), Canada (24), Germany (20), Italy (19), and France (14) follow suit, respectively. This is also similar to what Figure 6 suggests. For this reason, it is possible to argue that the authors who have published on Turkey circulate among Western institutions in their educational and vocational careers.

For the discipline of IR in particular, drawing influences from Acharya’s recent study,[xxxvii] which calls for the creation of “Global IR,” it could be suggested that much could come from the Turkish School of IR in creating Global IR, which respects diversity and aims at benefitting from different theoretical and methodological approaches as well as histories, cultures, and experiences of different nations and societies. While doing so, Acharya notes the risk of “neo-marginalization,” which means the respect of diversity being drawn to other outcomes that might damage the status of creating a Global IR. Thus, the scholars of the Turkish School of IR would make more solid contributions if they take this risk into account.

In addition, as highlighted by this study, Turkey, as a subject of study, is still in the margins of the broader center-periphery debate. Although the study of Turkey has expanded in the last two decades with new theoretical and methodological approaches, there is still more room to grow for the scholarship in Turkey. In addition, the scholars who study Turkey are educated in the institutions located at the center, which brings the question of “neo-marginalization” to the fore. Moreover, the studies on Turkey are published in journals that belong to Anglo-Saxon publishing companies, which necessitates a closer look into where Turkey is situated among the post-non-Western debates and localities. For this reason, the scholars coming from Turkey might reduce such obstacles and limitations by highlighting why different localities matter in IR and bringing Turkey to the fore as a case study.

These results reopen the discussions on academic imperialism,[xxxviii] academic dependency,[xxxix] and knowledge hegemonies.[xl] As Alatas[xli] reminds, “Today, academic imperialism is more indirect than direct.” It is concerning that what is valuable to study and research, who studies it, and what kind of knowledge produced is still controlled by the West. In our case, it is salient that the articles on Turkey that are published in Western journals, the authors that studied in the West, and the knowledge produced outside of Turkey are more visible and significant. Furthermore, when the theories and the concepts utilized in articles and dissertations[xlii] are considered, it is evident that Turkey’s academic dependency[xliii] and acknowledgement of its academic “vulnerability”[xliv] are still on the table. Studies on Turkey are still not equipped with their own theoretical and intellectual tools, and despite showing intellectual acceptance to new approaches and methods, they are constantly shopping these approaches from the West.

Research has shown that the IR discipline in Turkey and the studies that focus on Turkey have more to accomplish. For this reason, this paper aims to contribute to the Turkish School of IR by taking stock of the literature on the evolution and the current state of the discipline in Turkey by empirically analyzing all publications concerning Turkey in top-ranked IR journals.

As uncloaked by the literature, it could be argued that the Turkish School of IR[xlv] has made considerable progress in terms of theoretical and methodological contributions until the end of the Cold War. As seen in Figure 3, the considerable rise in interest in Turkey as the subject of study is also paving the way for scholars from the Turkish School of IR to reach out to a wider audience with their studies. Considered as a part of the “periphery,” Turkey is now a part of the areas of study in the “hegemonic” and “dominant” academic circles rooted in the Anglo-Saxon tradition. With the rise of Global IR, “peripheral” countries such as Turkey may be studied more in-depth not only by the “hegemon,” but also by the “periphery” itself. However, this is dependent on whether the “core” is ready to yield its dominance to the “periphery” and accept it to become an “equal” or “hegemonic.” As a further study, aiming to situate Turkish IR scholars in the wider discipline with their collegial ties, theoretical and methodological orientations, and approach to the discipline would be valuable to observe the core-periphery debates in IR.

Although the debut of IR to Turkey was immensely fresh and exciting, Turkish IR is non-visible in the Global, and Turkey is solely a hot case spot to provide newsworthy analysis for the Global. Furthermore, there is room for more progress in both theoretical and methodological areas. As shown by the analysis, the studies focusing on Turkey stay limited in utilizing theories and methodologies. As the discipline progresses along with new interdisciplinary and methodological innovations, studies focusing on Turkey and scholars from Turkey have numerous possible offerings to advance the discipline. As the discipline currently engages in the Global and Post-Western discussions, comparative studies using Turkey and scholars using new theoretical and methodological tools from Turkey can contribute significantly, as shown by this article.

The results of the analysis reveal several gaps and caveats for Turkish IR within the global. First and foremost, studies that focus on Turkey have been rapidly increasing over the last two decades. Secondly, Turkey is being studied in the top twenty IR journals, especially in the top ten journals, which show the increasing attention given to Turkey as a case study. However, the top IR journals are published either by the US or the UK, revealing the Western-centric dynamics of the discipline. Nevertheless, the issues studied in tandem with the case of Turkey center around the EU, identity, conflict, and terrorism. Moreover, this study also shows a lack of utilizing theoretical and methodological novelty in the study of Turkey. Thus, Turkish IR would benefit from attempting to fill those gaps. Finally, the number of other cases studied along with Turkey also highlights significant lacunae. For instance, Turkish IR would progress by conducting more comparative case studies, especially with understudied countries and/or issues within Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

Having noted such recent discussions in the field, it would be efficient to conclude this paper by pointing out some remarks on the limitations of this research and some possible further research items. First of all, although the observed journals’ databases offer a large dataset for the articles on Turkey, there are issues with the search filters. The filters within journals’ websites were often inefficient, which prevented relevant results from being prioritized. This could be a point of further improvement that needs to be addressed by journal administrators to give room for more convenient research. Moreover, on the authors’ side, the use of relevant keywords was sometimes misleading. For this reason, some articles might have been omitted from the analysis just because some articles focus on Turkey, although it is not stated in their keywords. Lastly, the focus on abstracts is also another limitation in this study, as they might have skewed the data in favor of the aforementioned findings. For instance, the majority of the articles may not have indicated their theoretical focus in their abstracts, which might have caused a high percentage of the lack thereof.

Further research might explore the recent studies produced by the Turkish School of IR by providing concrete data focusing on the journals the scholars of the Turkish School of IR published in, the theoretical approaches, and the methodologies they used. In addition, more research on the structural factors shaping the evolution of the Turkish School of IR could be an asset. Finally, to triangulate the data collected for this research, Google Scholar’s other relevant ranking list titled “Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies,” which consists of more journals that focus on Turkey, could be analyzed to garner more data on the issue.

Notes

[i] Amitav Acharya, “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds,” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647; Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan, “Why is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 287; Giorgio Shani, “Toward a Post-Western IR: The Umma, Khalsa Panth, and Critical International Relations Theory,” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 722.

[ii] Nilüfer Karacasulu, “International Relations Studies in Turkey: Theoretical Considerations,” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 8, no. 29 (2012): 147.

[iii] Boğaç Erozan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplininin Uzak Tarihi: Hukuk-ı Düvel (1859-1945),” Uluslararası İlişkiler 11, no. 43 (2014): 74.

[iv] The data covers all the departments carrying the name of International Relations: Middle East Political History and International Relations, Political Science and International Relations, International Relations, International Relations and European Union, and International Relations and Public Administration. The report was accessed online on August 3, 2021, through the following website: https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr/

[v] Seçkin Köstem, “International Relations Theories and Turkish International Relations: Observations Based on a Book,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 4, no. 1 (2015): 63.

[vi] Mustafa Aydın and Cihan Dizdaroğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 16, no. 64 (2019): 13.

[vii] Karacasulu, “International Relations Studies in Turkey,” 154.

[viii] İlter Turan, “Progress in Turkish International Relations,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 7, no. 1 (2018): 139.

[ix] Ersel Aydınlı and Gonca Biltekin, “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline,” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 283; Ersel Aydınlı, “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-reflections on Dialogue with the Core,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13, no. 2 (2020): 287; İsmail Erkam Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey: Methodology, Data Collection, and Data Repository,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no. 1 (2022): 123.

[x] Quan Li, “The Second Great Debate Revisited: Exploring the Impact of the Qualitative-Quantitative Divide in International Relations,” International Studies Review 21, no. 3 (2019): 1.

[xi] Emre İşeri and Nevra Esentürk, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları: Merkez-Çevre Yaklaşımı,” Elektronik Mesleki Gelişim ve Araştırma Dergisi 2, (2016): 29.

[xii] Pınar Bilgin and Oktay F. Tanrısever, “A Telling Story of IR in the Periphery: Telling Turkey About the World, Telling the World About Turkey,” Journal of International Relations and Development 12 (2009): 174.

[xiii] Ibid., 176.

[xiv] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations,” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 289; Peter Marcus Kristensen, “How Can Emerging Powers Speak? On Theorists, Native Informants and Quasi-Officials in International Relations Discourse,” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2015): 637-653.

[xv] Acharya and Buzan, “Why is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory?” 287.

[xvi] Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan, “Why is There no Non-Western International Relations theory? Ten Years On,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17, no. 3 (2017): 341.

[xvii] Vincent Larivière, Stefanie Haustein and Philippe Mongeon. “The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era,” PloS one 10, no. 6 (2015): 0-15; Steve Smith, “The United States and the Discipline of International Relations: ‘Hegemonic Country, Hegemonic Discipline’,” International Studies Review 4, no. 2 (2002): 67; Ole Wæver, “The Sociology of a Not so International Discipline: American and European Developments in International Relations,” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 687.

[xviii] Mehmet Akif Okur and Cavit Aytekin, “Non-Western Theories in International Relations Education and Research: The Case of Turkey/Turkish Academia,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 19-44.

[xix] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory Out of Anatolia,” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 697.

[xx] Karacasulu, “International Relations Studies in Turkey,” 148.

[xxi] Rahime Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm, “The Sociology of Diplomats and Foreign Policy Sector: The Role of Cliques on the Policy-Making Process,” Political Studies Review 19, no. 4 (November 1, 2021): 558–73.

[xxii] Simten Coşar and Hakan Ergül, “Free-Marketization of Academia Through Authoritarianism: The Bologna Process in Turkey,” A Journal of Critical Social Research 26, (2015): 106.

[xxiii] Simten Coşar and Hakan Ergül, “Free-Marketization of Academia through Authoritarianism,” 151.

[xxiv] Mustafa Aydın, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenlerinin Bilimsel Araştırma ve Uygulamaları ile Disipline Bakış Açıları ve Siyasi Tutumları Anketi,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 15 (2007): 2.

[xxv] Mathis Lohaus, Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and Olivia Ding, “Bifurcated Core, Diverse Scholarship: IR Research in Seventeen Journals Around the World,” Global Studies Quarterly 1, no. 4 (2021): 1; Mustafa Aydın and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Araştırma, Eğitim ve Disiplin Değerlendirmeleri Anketi – 2009,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 7, no. 25 (2010): 5; eds. Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, International Relations Scholarship Around the World (New York: Routledge, 2009): 5.

[xxvi] Mustafa Aydın, Fulya Hisarlıoğlu, and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Alana Yönelik Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir İnceleme: TRIP 2014 Sonuçları,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 14.

[xxvii] Mustafa Aydın and Cihan Dizdaroğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları,” 12.

[xxviii] The figures include the responses to the question on “the use of theories” by the survey respondents.

[xxix] The 2009 survey was not conducted in other countries and therefore is omitted from the graph.

[xxx] Resul Ümit, “Turnaround Times and Acceptance Rates in Political Science Journals,” Blog. July 6, 2021. https://resulumit.com/blog/polisci-turnaround-acceptance/

[xxxi] Hakan Mehmetcik and Hakan Hakses, “Turkish IR Journals Through a Bibliometric Lens,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 61-84.

[xxxii] As the TRIP survey indicates, the respondents use theories quite frequently. However, the abstract analysis of this study shows that many of them lack a theoretical focus in their abstracts. This might have arisen from TRIP’s use of survey methodology, while we manually code the abstracts. Secondly, as a limitation of this study, although some of the articles might have used a theoretical lens, they were not mentioned in the abstract.

[xxxiii] Ersel Aydınlı, “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 8, no. 2 (2019): 109-115; İsmail Erkam Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey,” 123-42.

[xxxiv] Çiğdem Kentmen-Çin and Ebru Canan-Sokullu, “Uluslararası İlişkiler Öğrencisinin Sayılardan Korkusu ve Bu Korkuyu Aşmanın Yolları,” in Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Eğitimi: Yeni Yaklaşımlar, Yeni Yöntemler [International Relations Education in Turkey: New Approaches, New Methods], ed. Ebru Canan-Sokullu (İstanbul, Turkey: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2018): 209-32.

[xxxv] Derya Göçer and Özgehan Şenyuva, “Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplini ve Niteliksel Yöntem: Türkiye’de Göç Çalışmaları Örneği,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 18, no. 72 (2021): 19-36.

[xxxvi] Nil S. Şatana, “Uluslararası İlişkilerde Bilimsellik, Metodoloji ve Yöntem,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 46: 11-33.

[xxxvii] Amitav Acharya, “Global International Relations,” 656.

[xxxviii] Calvin W. Stillman, “Academic Imperialism and Its Resolution: The Case of Economics and Anthropology,” American Scientist 43, no. 1 (1955): 77–88; Esmaeil Zeiny, “Academic Imperialism: Towards Decolonisation of English Literature in Iranian Universities,” Asian Journal of Social Science 47, no. 1 (2019): 88–109; Syed Hussein Alatas, “Academic Imperialism,” the History Society (class lecture, University of Singapore, Queenstown, SG, 1969).

[xxxix] Syed Farid Alatas, “Academic Dependency and the Global Division of Labour in the Social Sciences,” Current Sociology 51, no. 6 (2003): 599-613; Fernanda Beigel, “Academic Dependency,” Alternautas 2, no. 1 (2015): 60-2; Jinba Tenzin and Lee Chengpang, “Are We Still Dependent? Academic Dependency Theory After 20 Years,” Journal of Historical Sociology 35, no. 1 (2022): 2-13.

[xl] Syed Farid Alatas, “Knowledge Hegemonies and Autonomous Knowledge,” Third World Quarterly (2022): 1-18.

[xli] Syed Farid Alatas, “Academic Imperialism.”

[xlii] Özge Özkoç and Pınar Çağlayan, “The Trajectory of International Relations Dissertations in Turkish Academia Between 2000 and 2020,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 107-128.

[xliii] Academic dependency refers to intellectually dependent societies who need to borrow the academic tools of Western social science in order to make sense of their own sociality (Alatas, 2003).

[xliv] Kyriakos Mikelis, “Lessons Learned from the Development of Turkish IR: A View from Greece,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 45-60.

[xlv] It would also be beneficial to reiterate that the term “Turkish School of IR” is solely used to denote the community of scholars contributing to the International Relations discipline by focusing on Turkey. For this reason, this paper does not aim at establishing judgmental claims on whether there is a Turkish School of IR or not.

Acharya, Amitav. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647-659.

Acharya, Amitav and Barry Buzan. “Why is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 287-312.

Acharya, Amitav and Barry Buzan.“Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? Ten Years On.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17, no. 3 (2017): 341-370.

Alatas, Syed Farid. “Academic Dependency and the Global Division of Labour in the Social Sciences.” Current Sociology 51, no. 6 (2003): 599-613.

Acharya, Amitav and Barry Buzan. “Knowledge Hegemonies and Autonomous Knowledge.” Third World Quarterly (2022): 1-18.

Acharya, Amitav and Barry Buzan. “Academic Imperialism.” The History Society. Class lecture, University of Singapore, Queenstown, SG, 1969.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenlerinin Bilimsel Araştırma ve Uygulamaları ile Disipline Bakış Açıları ve Siyasi Tutumları Anketi [Survey of Turkish International Relations Scholars’ Scientific Research and Practices Based on their Disciplinary Perspectives and Political Dispositions].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 15 (2007): 1–31.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Cihan Dizdaroğlu. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme [International Relations in Turkey: An Assessment of the Results of the 2018 TRIP Survey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16, no. 64 (December 1, 2019): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.33458/uidergisi.652877.

Aydın, Mustafa, Fulya Hisarlioğlu, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Alana Yönelik Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir İnceleme: TRIP 2014 Sonuçları [An Investigation of International Relations Academics and their Approaches to the Field: TRIP 2014 Results].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 3–35.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Araştırma, Eğitim ve Disiplin Değerlendirmeleri Anketi-2009 [Survey of Turkish International Relations Academics’ Assessment on Research, Education and the Discipline -2009].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 7, no. 25 (2010): 3–42.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Eğitim, Araştırma ve Uluslararası Politika Anketi-2011 [International Relations Scholars in Turkey Education, Research, and International Politics Survey-2011].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 9, no. 36 (2013: 3-44.

Aydınlı, Ersel. “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 8, no. 2 (2019): 109-115.

Aydınlı, Ersel.“Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-reflections on Dialogue with the Core,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13, no. 2 (2020): 287-312.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline.” International Studies Perspectives 18 (2017): 267-287.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 289-303.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693-712.

Beigel, Fernanda. “Academic Dependency.” Alternautas 2, no. 1 (2015): 60-62.

Bilgin, Pınar, and Oktay F. Tanrısever. “A Telling Story of IR in the Periphery: Telling Turkey About the World, Telling the World About Turkey.” Journal of International Relations and Development 12 (2009): 174-179.

Coşar, Simten and Hakan Ergül. “Free-Marketization of Academia through Authoritarianism: The Bologna Process in Turkey.”A Journal of Critical Social Research 26, (2015): 101-124.

Erozan, Boğaç. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplininin Uzak Tarihi: Hukuk-ı Düvel (1859-1945) [A Long History of the International Relations Discipline in Turkey: International Law.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 11, no. 43 (2014): 53-80.

Göçer, Derya and Şenyuva, Özgehan. “Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplini ve Niteliksel Yöntem: Türkiye’de Göç Çalışmaları Örneği [The Discipline of International Relations and Qualitative Methods: Migration Studies in Turkey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 18, no. 72 (2021): 19-36.

İşeri, Emre and Nevra Esentürk. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları: Merkez-Çevre Yaklaşımı [International Relations Studies in Turkey: Center-Periphery Perspective].” Elektronik Mesleki Gelişim ve Araştırma Dergisi 2016, no. 2 (2016): 17–33, www.ejoir.org.

Karacasulu, Nilüfer. “International Relations Studies in Turkey: Theoretical Considerations.” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 8, no. 29 (2012): 143-160.

Kentmen-Çin, Çiğdem and Canan-Sokullu, Ebru. “Uluslararası İlişkiler Öğrencisinin Sayılardan Korkusu ve Bu Korkuyu Aşmanın Yolları [International Relations Students' Fear of Numbers and How to Overcome this Fear].” In Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Eğitimi: Yeni Yaklaşımlar, Yeni Yöntemler [International Relations Education in Turkey: New Approaches, New Methods, edited by Ebru Canan-Sokullu, 209-232. İstanbul, Turkey: Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2018.

Köstem, Seçkin. “International Relations Theories and Turkish International Relations: Observations Based on a Book.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 4, no. 1 (2015): 59-66.

Kristensen, Peter Marcus. “How Can Emerging Powers Speak? On theorists, Native Informants and Quasi-Officials in International Relations Discourse.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2015): 637-53.

Larivière, Vincent, Stefanie Haustein, and Philippe Mongeon. “The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era.” PloS one 10, no. 6 (2015): 1-15.

Lohaus, Mathis, Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and Olivia Ding. “Bifurcated Core, Diverse Scholarship: IR Research in Seventeen Journals around the World.” Global Studies Quarterly 1, no. 4 (2021): 1-16.

Li, Quan. “The Second Great Debate Revisited: Exploring the Impact of the Qualitative-Quantitative Divide in International Relations.” International Studies Review 21, no. 3 (2019): 447-476.

Mehmetcik, Hakan, and Hakan Hakses. “Turkish IR Journals through a Bibliometric Lens.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 61-84.

Mikelis, Kyriakos. “Lessons Learned from the Development of Turkish IR: A View from Greece.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 45-60.

Okur, Mehmet Akif, and Cavit Aytekin. “Non-Western Theories in International Relations Education and Research: The Case of Turkey/Turkish Academia.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 19-44.

Özkoç, Özge, and Pınar Çağlayan. “The Trajectory of International Relations Dissertations in Turkish Academia Between 2000 and 2020.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 12, no. 1 (2023): 107-128.

Shani, Giorgio. “Toward a post-Western IR: The Umma, Khalsa Panth, and Critical International Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 722-734.

Smith, Steve. “The United States and the Discipline of International Relations: ‘Hegemonic Country, Hegemonic Discipline’.” International Studies Review 4, no. 2 (2002): 67-85.

Stillman, Calvin W. “Academic Imperialism and Its resolution: The Case of Economics and Anthropology.” American Scientist 43, no. 1 (1955): 77–88.

Sula, İsmail Erkam. “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey: Methodology, Data Collection, and Data Repository.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no. 1 (2022): 123-42.

Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm, Rahime. “The Sociology of Diplomats and Foreign Policy Sector: The Role of Cliques on the Policy-Making Process.” Political Studies Review 19, no. 4 (November 1, 2021): 558–73.

Şatana, Nil S. “Uluslararası İlişkilerde Bilimsellik, Metodoloji ve Yöntem [Scientificity, Methodology and Method in International Relations].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 12, no. 46 (2015): 11-33.

Tenzin, Jinba, and Chengpang Lee. “Are We Still Dependent? Academic Dependency Theory After 20 Years.” Journal of Historical Sociology 35, no. 1 (2022): 2-13.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Wæver (edited by). International Relations Scholarship Around the World. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Turan, İlter. “Progress in Turkish International Relations.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 7, no. 1 (2018): 137-42.

Umit, Resul. “Turnaround Times and Acceptance Rates in Political Science Journals.” Blog. July 6, 2021. https:// resulumit.com/blog/polisci-turnaround-acceptance/

Wæver, Ole. “The Sociology of a Not So International Discipline: American and European Developments in International Relations.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 687-727.

Zeiny, Esmaeil. “Academic Imperialism: Towards Decolonisation of English Literature in Iranian Universities.” Asian Journal of Social Science 47, no. 1 (2019): 88-109.