Hayriye Kahveci

Middle East Technical University, METU Northern Cyprus Campus

Işık Kuşçu Bonnenfant

Middle East Technical University

The end of the Cold War brought about new challenges and opportunities for Turkey in redesigning its foreign policy. The independence of the Central Asian countries, with which Turkey shares common cultural, historical, and linguistic features, prompted Turkey to rapidly adapt to the new environment in the post-Cold War world order. After three decades, Turkey’s engagement with the Central Asian republics has gradually increased and reached a level at which Turkey is capable of effectively combining its soft and hard power capabilities within regional parameters. This article critically analyzes 30 years of Turkish foreign policy in Central Asia with a focus on its regionalism and soft power elements. We argue that Central Asia has provided a unique opportunity for Turkey to reshape its foreign policy on regional terms by utilizing its soft power resources for the first time, the experience later serving as a model for other regions. and its now hegemonic position in Lebanese politics.

Turkish foreign policymakers faced a series of challenges at the end of the Cold War. The unpredictability of the new period and the uncertainty about Turkey’s future role in global politics was a primary source of concern. More specifically, the fear that the collapse of the Soviet Union would diminish NATO’s position and the possible lessening of the strategic role that Turkey had played during the Cold War period were pressing issues. Since the foundation of the republic, Turkey had had a Western orientation in shaping its relations with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The collapse of the Soviet Union posed a challenge to Turkey’s decades-long strategic-ally role for the West; it also introduced a new group of neighbors with which Turkey had to establish relationships.

The new period played a transformative role that led to Turkey’s pursuit of a new foreign policy path. The independence of the Central Asian states, having historical, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds in common with Turkey, stirred the emotions of Turkish nationalist groups and created domestic political pressure on Turkish leadership to have a more active role in the region.[1] Furthermore, the region’s transformation occurred during an era of power shift in the Global East, as Gökay would call it, in which Turkey was poised to occupy an increasingly important role.[2] This context presented political and economic opportunities for Turkey in the post-Cold War environment. In addition, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant that Central Asia—and the broader post-Soviet geography—was now available for Turkish goods in a new market, evoking a broader economic role for Turkey in the region. In terms of foreign policy, the region also presented an opportunity for a new geopolitical role for Turkey after the Cold War. This new position could eliminate the risk of the country’s declining geopolitical importance and create dynamism in its relations with the rest of the world. To be successful, Turkey needed to improve the changing geopolitical setting and address domestic political demands while creating a foreign policy approach that could accommodate international realities.

Through an in-depth analysis of 30 years of Turkish foreign policy in Central Asia, we aim to trace the regionalism and soft power elements of Turkish foreign policy, mainly attributed to the Justice and Development Party (JDP) governments since 2002. We argue that, coupled with the global economic dynamics, this process started as early as 1991 with Turkey’s unique experience in Central Asia, which contributed to shaping its foreign policy within regional parameters and its ability to use soft power capabilities in other regions. For Turkey, the knowledge and skills acquired during the process have enabled the country to become a more vigorous, multi-regional actor, one capable of using various soft power instruments elsewhere. This article first reviews the scholarly debate on regionalism and soft power in Turkish foreign policy. It then focuses on Turkey’s endeavors in designing a foreign policy towards Central Asia from 1991 to 2002, concentrating on the initial discourse and practices of regionalism and soft power. Thirdly, it examines Turkey’s policies in Central Asia since 2002 with a focus on institutions and policies that clearly improved its regionalist perspective and soft power capabilities.

The end of the Cold War led to a new wave of regionalism, with states feeling less limited by bipolar divisions and urgencies. Regionalism reemerged globally, and states tended to collaborate more to overcome regional problems.[3] The US’s global hegemonic role and capabilities were under scrutiny in the post-Cold War environment.[4] Around this time, Joseph Nye came up with the concept of soft power.[5] Nye argued that “…the definition of power is losing its emphasis on military force and conquest that marked earlier eras. The factors of technology, education, and economic growth are becoming more significant in international power, while geography, population, and raw materials are becoming somewhat less important.”[6] Nye believes that soft or co-optive power is as important as hard power in terms of agenda-setting and the structuring of international politics since it can make states seem legitimate in others’ eyes. In addition, states that use soft power may encounter less resistance to their wishes. If a state’s culture and ideology are attractive and less threatening, other states may be more inclined to accept and follow.[7]

For Nye, “The major elements of a country’s soft power include its culture (when it is pleasing to others), its values (when they are attractive and consistently practiced), and its policies (when they are seen as inclusive and legitimate).”[8] The success of soft power rests on various factors, one of which is the government's realization and utilization of soft power assets in a correct and acceptable manner.[9] Utilization of soft power in foreign policy lies in a state’s ability to base its policies on contextual intelligence formed by diagnostic skills to understand its strengths and weaknesses.[10] A combination of hard and soft power elements based on contextual intelligence is the basis for developing intelligent foreign policy strategies.[11] According to Çevik, soft power resources and the knowledge of how to use them to one’s benefit are two different things. However, without the substantial backing of hard power, soft power alone cannot be or become an important asset.[12] Karadağ, on the other hand, emphasized the role of military power, which is commonly defined as an element of hard power, as a potential tool of public diplomacy and soft power as well.[13]

Turkish foreign policy practitioners were strongly influenced by these ideas as Turkey was in the process of defining its identity in the post-Cold War context. The new period provided challenges and opportunities because many of the newly-independent states were located in regions neighboring Turkey, and Turkey was compelled to design its foreign policy in regional terms. The Central Asian republics, which were previously part of the Soviet Union, were now states with which relations could be directly established without dealing with Moscow. As these states have common cultural, historical, and linguistic ties with Turkey, foreign policymakers started to envision Central Asia as a region with which Turkey could form strong, direct relationships utilizing these common ties (soft power resources).

Kaliber defines this period as the first regionalist phase of Turkish foreign policy. He argues that while regionalist thinking is attributed to the JDP foreign policy elites, this is indeed a process that had started much earlier.[14] Bilgin and Bilgiç argue that the Turkish political elite of the 1990s, such as Turgut Özal, Süleyman Demirel, and İsmail Cem, are the primary architects of this regionalist vision.[15] They also highlight that İsmail Cem, who served as a Foreign Minister from 1997–2002, created a new geographic imagination that placed Turkey at the center of regions such as Central Asia and the Middle East. Yeşiltaş claims that Cem created a unique geopolitical discourse that emphasized Turkey’s cultural and civilizational identity in Eurasia, one which has elements from both the East and the West.[16] All of these arguments suggest that when the JDP came to power in 2002, the idea about a new pivotal role for Turkey in diverse regions, a role that enabled it to use its soft power resources as assets, was already in place.

As of 2002, JDP elites advanced this image of Turkey with a more elaborate geopolitical discourse. Because he was a scholar of International Relations, the discussion was largely shaped by Ahmet Davutoğlu, who served as a Foreign Minister (2009–2014) and Prime Minister (2014–2016). Turkey was depicted as a pivotal actor in a vast geography capable of utilizing its ample soft and hard power resources to provide peace and stability in various regions.[17]

The concept of soft power and Turkey’s utilization of its extensive soft power resources to become an effective actor in a regional context was a central theme in Davutoğlu’s new geopolitical discourse.[18] It was during this period that the Turkish political elite often resorted to this concept to emphasize the transformation of Turkish foreign policy, often in binary opposition to the “old” foreign policy practices occurring before the JDP’s rule.[19] Çevik argues that after the introduction of the soft power concept with regard to a more assertive foreign policy by the mid-2000s, it became a prominent one in popular discourse as well.[20] Scholarly literature on the role of soft power in Turkish foreign policy also proliferated around this time.[21]

However, in the last decade or so, due to problems Turkey has encountered at the policy level in volatile neighboring regions, the limitations of Davutoğlu’s geopolitical discourse have become clear. This is partly due to Turkey’s overextension of its resources in a vast region and because of an overly ambitious discourse and agenda. Kutlay and Öniş argue that by returning to early JDP-era foreign policy practices, which had focused on soft power capabilities and the principle of non-interventionism and multilateral diplomacy, Turkey could still play an active regional and global role worthy of its resources.[22] Central Asia is a region in which Turkey’s foreign policy followed a balanced, steady course of action. The country had learned the lessons of its overenthusiasm about and overstretching of its resources earlier on. In the following sections, we will discuss how this process evolved and matured to a level at which Turkey has become an important regional actor that skillfully uses its soft power resources.

Since the Republic of Turkey’s establishment, relations with the Turkic peoples of the Soviet Union had been shaped through and with Moscow. From 1988 onwards, Gorbachev’s policies enabled small-scale foreign relations with individual Socialist Republics. Turkey used this to establish relations with the Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union. A bilateral cooperation protocol to establish cooperation on science and education, press and publishing, tourism, radio and TV broadcasting, transportation, economic and trade relations, and in-service training, was signed with the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) during Turkish Minister of Culture Namık Kemal Zeybek’s visit on December 5th, 1990, is an example of this. On February 14th, 1991, another cooperation agreement was signed with the Kazakh SSR by the Ministries of Health.[23] Yet, despite these initial contacts with the Turkic SSRs, Turkey was following a cautious policy to make it clear that it had no intention of harming relations with Moscow.[24]

A further expansion of relations began with former Turkish President Özal’s March 1991 visit to the USSR, which began in Moscow and then continued to the SSRs of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine.[25] During his visits, a series of cooperation agreements were signed with the Soviet Union on friendship and cooperation in the realms of economy and trade, telecommunications, transportation, and broadcasting. Accompanied by a group of businessmen, Özal’s inclusion of Moscow and Kiev in his itinerary meant to reassure Moscow that Turkey did not intend to focus solely on the Turkic states.[26] The visit was parallel to initial contacts established with the Central Asian states starting from 1988 onwards and did not represent an agenda change in terms of Turkish foreign policy towards the Soviet Union. Central Asia was still considered within the framework of relations with Moscow, in line with the Treaty of Brotherhood signed between Lenin and Atatürk in 1921. From Turkey’s perspective, the changes the USSR was experiencing through Glasnost and Perestroika presented opportunities for further economic cooperation with Moscow, but Turkey preferred to maintain a careful distance from the internal problems that the Soviets were experiencing until the collapse of the USSR in 1991.[27] In this regard, although pre-independence contacts could be considered signs of Turkish interest in the region, it is not possible to talk about Turkish foreign policy towards Central Asia prior to the USSR’s demise.

After the dissolution, however, Turkey had to decide what kind of an approach to follow towards the region, especially towards the Turkic republics, which Turkey had historical, cultural, and linguistic affinities with. The declarations of independence of 15 countries in Turkey’s neighborhood, six of them having religious, ethnic, and cultural similarities with Turkey, were received with excitement, and considered to be quite promising in terms of new regional economic and political positioning. For the Turkish political elite and for the West, Turkey had an essential part to play in Eurasia in this unique geopolitical setting. For the West, a robust Turkish role was necessary in order to fill the power vacuum left behind after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and also to create a barrier against the expansion of radical Islam and Iranian influence in the region.[28] Besides, for the US, as the primary hegemonic power after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Turkey’s role as a regional player in Central Asia was crucial for the protection of American geo-strategic interests in the region. In this context, Turkey emerged as a model of secular democracy for the newly-independent states of the region.

“The Turkish Model” was used by Catherine Lalumiere, the secretary-general of the Council of Europe in 1992, to define a post-Soviet path for these regional Muslim states. The term refers to Turkey as a Muslim state that is secular, pro-Western, in possession of a multi-party system, and that uses a free-market economic model. The idea of a “Turkish Model” had its own problems as well since it somehow caught Turkish foreign policymakers by surprise. At the end of the Cold War, Turkey was still a country struggling to complete its own economic and political transformation and hoping to attain the level of its Western counterparts.[29] Despite not being a home-grown strategy, becoming a developmental model for newly-independent countries had its attraction and benefits. For Turkish foreign policymakers, the region presented an opportunity to establish a niche in the post-Cold War world. The collapse of the Soviet Union created new security threats emanating from the uncertainties regarding the path that newly-independent states would follow. As a long-standing and reliable member of NATO, Turkey had a strategic role to play in integrating the newly-independent Turkic states into the international community. This role would also contribute to Turkey’s international standing and lead to its emergence as an important regional player.[30]

Similar to other members of the international community, the primary challenge for Turkish leadership during this period was a lack of information and understanding about the newly-independent states and what they required from various international actors, and most importantly from Turkey. In terms of Turkish foreign policymaking towards Central Asia, the initial years were turbulent since emotions, regional leadership aspirations, lack of a clear regional target, and limited capabilities characterized policy choices. On the one hand, the Turkish leadership had to establish a balance between the country’s historical foreign policy orientation, which followed a careful approach towards Turkic peoples living outside of Turkey, and the rising domestic nationalist hopes for a greater regional role towards a Turkic union. On the other hand, the Turkish leadership had to gain an upper hand in a competition of regional leadership played by countries like Iran in the absence of Russian dominance. In the wake of such urgency, Turkey tried to achieve quite a number of things on different fronts, and these were sometimes not thoroughly planned.

After the coup attempt in Moscow in August 1991, a special committee was established to assess Central Asia and the Caucasus. In September 1991, the committee went first to Azerbaijan[31] and then to Central Asia to evaluate, firsthand, post-coup attempt developments in Central Asia and the Caucasus.[32] The committee report indicated that regional leaders (except those in Kazakhstan, who did not declare independence at the time) were ready to establish diplomatic relations and cooperation with Turkey in the fields of economy and education. Following the declaration establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in December 1991, Turkey was the first to extend diplomatic recognition to all of the former Soviet Republics.

The reciprocal visits of Central Asian leaders to Turkey and that of Turkish leaders to Central Asia began even before the official extension of diplomatic recognition. They resulted in the signing of numerous bilateral agreements and statements of willingness to increase cooperation.[33] In September 1991, the President of the Kazakh SSR, Nursultan Nazarbayev, was the first Central Asian leader to visit Turkey.[34] In a statement to the press, he described the 21st century as the century of the Turks, one in which he wanted to benefit from Turkey’s experiences in the transition to a market economy.[35] In his December 1991 visit to Turkey, the President of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, described Turkey as a model and as a big brother from whom he was willing to get support on economic, political, and cultural issues. As a result of the continued deepening of relations, by the end of the first year, following the independence of the Central Asian states, 1,170 Turkish delegations visited the region and more than 140 bilateral agreements had been signed.[36]

In February 1992, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hikmet Çetin, visited Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan, where multiple cooperation agreements were signed, including a visa waiver agreement. Çetin’s visit was then followed by the Turkish Prime Minister’s (Süleyman Demirel) visit to the region in 1992, which focused on cooperation in economic, educational (i.e., provision of scholarships for regional students), and transportation issues. During the visit, energy cooperation between Turkey and Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan occupied a large portion of Demirel’s agenda. As early as May 1992, the financial aid and credit promises of the Demirel leadership amounted to over 1.1 billion dollars, which was already a significant burden on the Turkish economy.[37]

In order to regulate financial aid, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs went through a period of restructuring by establishing separate departments to deal with the affairs of the former Soviet Union; this was a strong indicator of its regionalist vision and about the unique place of Central Asia within it. In January 1992, a development aid organization, the Turkish International Cooperation Administration (TİKA), was established under the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its aim was to specifically address the developmental needs of the Turkic republics.[38] Throughout the 1990s, 270 technical aid and development projects were developed under TİKA’s auspices towards Central Asia and the Caucasus. The financial and technical support transferred through TİKA constituted a crucial part of Turkey’s soft power policies in the region. Through this organization, Turkey gained the capacity to be an active donor country in the region.[39] During the period of 1992–1996, Central Asia and the Caucasus were beneficiaries of 86.5% of the Turkish government’s official development aid budget. This declined to 40% between 1997 and 2003. During this period, the organization was restructured under the Prime Ministry, and its focus had then expanded to the Balkans and Eastern Europe.[40]

Another indicator of Turkey’s regionalist vision in its foreign policy towards Central Asia was the multilateral platform called the Summits of the Heads of Turkic Speaking States. The first meeting was held on October 30–31, 1992, in Ankara. Özal’s speech from the summit, which highlights close cooperation in various areas such as economics, energy, an integrated infrastructure system in transportation, telecommunications, banking, and joint discussions on issues that were internationally and regionally important, reveals the ambitious prospects of cooperation in the initial years.[41]

However, while the Ankara Declaration signed at the end of the summit vaguely focused on the commitment of all parties to cooperate on matters of culture, education, language, security, economy, and legal issues,[42] Turkey’s aim to boost ties through cooperation under Turkish leadership was not readily accepted by the other actors involved. This can be attributed to the Central Asian leaders’ not being completely comfortable with Turkey’s overtures for regional leadership in a big brother-type role. These new nations were struggling to consolidate their independence from a major power that had dominated them for almost a century. Still, eight additional summits were organized up until the 2009 Nakhchivan Summit, where the agreement establishing the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States (renamed as the Organization of Turkic States in 2021) as a permanent international organization with headquarters in Istanbul was signed. The regular occurrence of these summits and the fact that these events eventually became an international organization is a clear sign of the institutionalization of relations based on collective interests and cooperation.

Starting from the mid-90s, Turkish foreign policy towards Central Asia became visibly more pragmatic and realistic because of the country’s limited economic capabilities and Russian recovery of influence over the republics. Despite Turkey’s goodwill and generosity, its economic limitations in meeting the developmental needs of the Central Asian republics became apparent over time. The newly-formed countries were in dire need of financial and technical support for their state-building processes, and Turkey was falling short of meeting those expectations. Moreover, contrary to an initial promise of an active Turkish business involvement in the regional states’ economies, this soon proved to be unrealizable to the degree expected because, except for the energy resources of some, the republics did not have a rich export market or even goods that could lead to increased trade collaboration. As a result, in many instances, this was only a one-way product transfer from Turkey.[43] Furthermore, the lack of necessary institutional frameworks that normally provide a competitive and secure business environment, as well as the presence of strong economic ties and relations inherited from the former Soviet system were considered limitations to business prospects by Turkish investors.[44]

Despite the obstacles encountered during the early years, once Turkey established a more balanced approach towards the region, accommodating its soft power assets with its political, economic, and geopolitical realities, its foreign policy started to produce results that set the tone for its level-headed relations with the countries of the region, and this continues even now, in the present. What is more important with regard to the main argument of this article is that many of the soft power institutions and tools Turkey created in this period later served as a basis and a model for Turkish foreign policy in other geographical locales.

Based on common linguistic, historical, and religious heritage, Turkey developed various soft power instruments, enabling it to become a significant regional actor. One of the longest-lasting cultural initiatives has been the television broadcasting initiated by TRT (Turkish Radio and TV Corporation). TRT Avrasya (Eurasia) started broadcasting various programs targeting the Turkic world in 1992. TURKSOY was established in 1993, with Turkey’s initiative, as a multilateral international organization with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan as co-founding members. It has been working towards the protection of Turkic culture, art, language, and historical heritage, introducing these values, and transferring these and other concepts to future generations, while also increasing their exposure to the world.[45] Such a relationship was not visible in relations with Tajikistan, who does not share similar cultural or linguistic characteristics with Turkey.

In the religious realm, Turkey has also cooperated closely with the Central Asian republics since the early 1990s. The Eurasian Religious Council is a product of these collaborative efforts. The institution was formed in 1994 to promote Turkey’s religious outreach into Central Asia, along with the Caucasus, Balkans, and Russia’s autonomous republics.[46] Balcı defines the council’s purpose as wanting “to facilitate dialogue about the proper relationship between Islam and the state and the role of Islam in society.”[47] Turkey’s Diyanet (The Presidency of Religious Affairs) has also been a key institution in reaching the Central Asian republics in a spiritual way. Together with the Diyanet Foundation, it has helped build and restore mosques, trained the new religious elite, and distributed religious publications originally printed in Turkey.[48] Turkey’s influence via the Diyanet in Central Asia (and in other parts of the world) can be evaluated as an example of transnational Islam and forms a core element of Turkish political and cultural influence in the region. However, another form of cultural outreach even preceded religious networking in Turkey’s soft power approach to Central Asia.

Turkey’s educational policies towards the region can perhaps be evaluated as another major attempt to reflect its soft power with long-term goals. In this regard, the establishment of scholarships and the opening of schools and education centers can be listed as some of Turkey’s additional soft power assets in the region. A major initiative was the Great Student Exchange Program, which was developed by the Ministry of Education and started in the 1992–1993 academic year.[49] The program aimed to distribute scholarships specifically to undergraduate and graduate students from Central Asia, enabling them to study at Turkish universities. According to Engin-Demir and Akçalı, the program aimed “to increase the educational level of the population in Turkic republics, to create generations familiar and sympathetic to the Turkish culture and to provide trained manpower in these republics.”[50]

In addition to providing scholarships to Central Asian students to study in Turkey, the Turkish Ministry of Education has established various educational centers including elementary, secondary, and higher education institutions abroad.[51] The Ministry provides these schools with some of their teachers and administrative personnel.[52] There are also Turkish language learning centers in the capitals of each Central Asian republic, except in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.[53] Finally, there are two universities in the region, established in 1993 and 1995, on the basis of bilateral agreements: Turkish-Kazakh International Hoca Ahmet Yesevi University in Turkestan (Kazakhstan) and Turkish-Kyrgyz Manas University in Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan).[54]

With JDP’s rise to power in 2002, Turkey’s foreign policy towards Central Asia entered its second regionalist phase. The JDP’s first government initiative emphasized its commitment to preserving the current balanced policy towards Russia and Central Asia. However, while the program defined Russia as a neighbor, the Turkic states were portrayed as having a unique place because of their shared culture with Turkey.[55] The difference was further emphasized in the 2007 program, in which the Central Asian states were considered siblings of Turkey that the country felt historical responsibility for.[56] Overall, JDP policies towards Central Asia were persistent and did not show any major deviation from earlier periods. The JDP’s ability to maintain single-party power and Turkey’s steady economic growth as of the mid-2000s positively affected the country’s soft power capabilities in terms of the proliferation of its tools and the presence and back up of hard power instruments.[57]

The most striking aspect of the post-2002 soft power involvement of Turkey has been in the economic domain. It is possible to analyze this involvement on two fronts. On the one front, Turkey’s soft power elements in the region take the form of trade relations and investment activities of Turkish companies. On the other hand, though diminishing over the years, development aid continued to form an important part of Turkey’s economic soft power over the region. Developing strong economic ties with Central Asia had been a major goal of Turkish foreign policy from the early 1990s until around 2000. However, due to the problems related to the Turkish economy and to that of the Central Asian republics as discussed earlier, economic relations did not show much progress during this period. With Turkey’s steady economic growth as of the mid-2000s, the country became a more assertive and capable actor in terms of expanding its economic influence in Central Asia, along with other regions. According to Bülent Gökay, this was very much related to the strengthening of Turkey’s economic position in the world economy, which also explains the country’s progress towards becoming both a middle power and regional leader. Gökay argues that this is the result of two parallel processes: at the global level, a major shift in global economic power “from the developed West and North to the underdeveloped East and South” and, at the domestic level, the neoliberal transformation of the Turkish economy.[58] As a result of these concurrent developments, with its strong and dynamic business sector, successful financial restructuring, and fast export-oriented industrialization, Turkey began to explore economic opportunities in neighboring regions. Burgeoning economic and business ties with the Central Asian republics as of the mid-2000s should be considered part of this general trend.

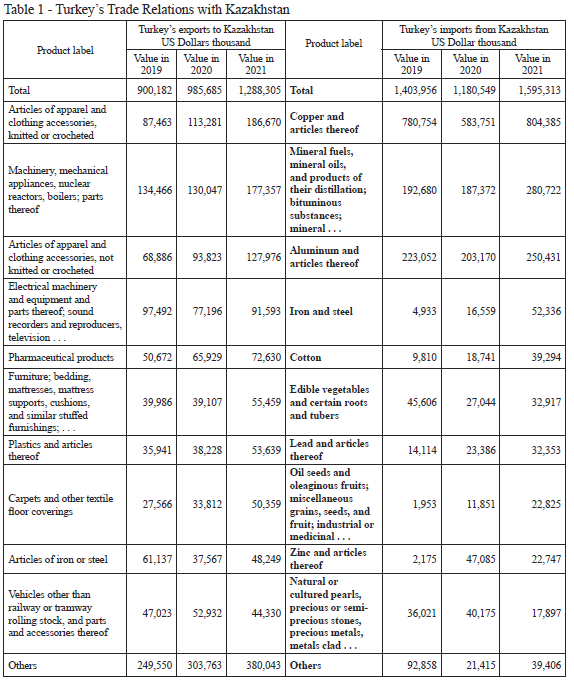

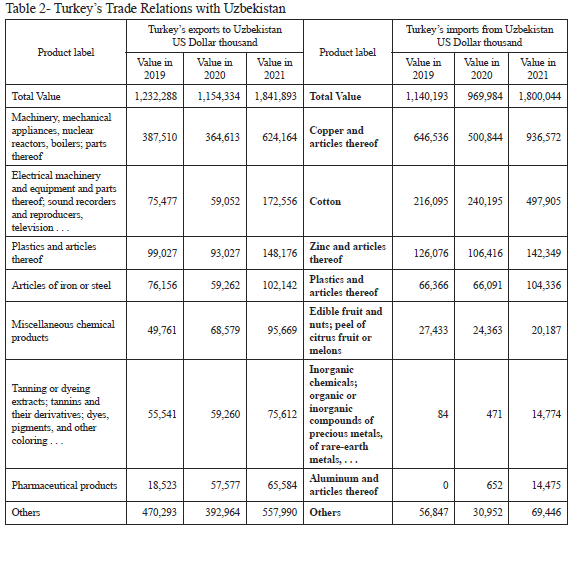

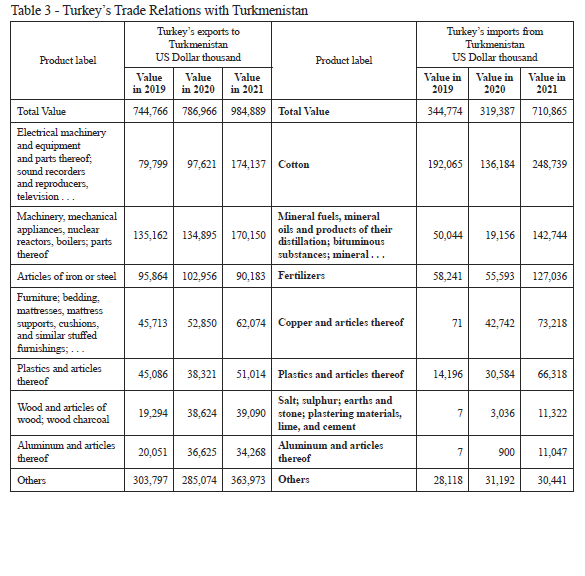

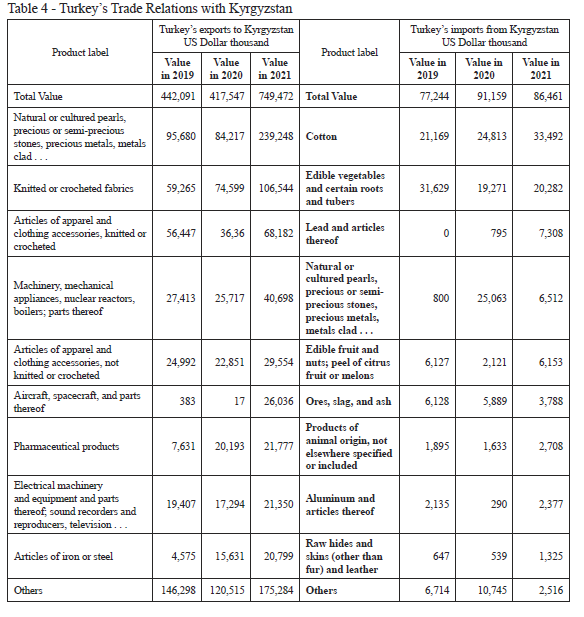

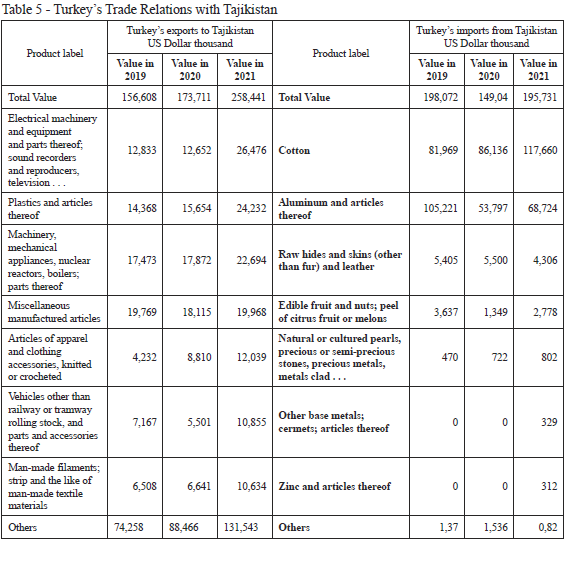

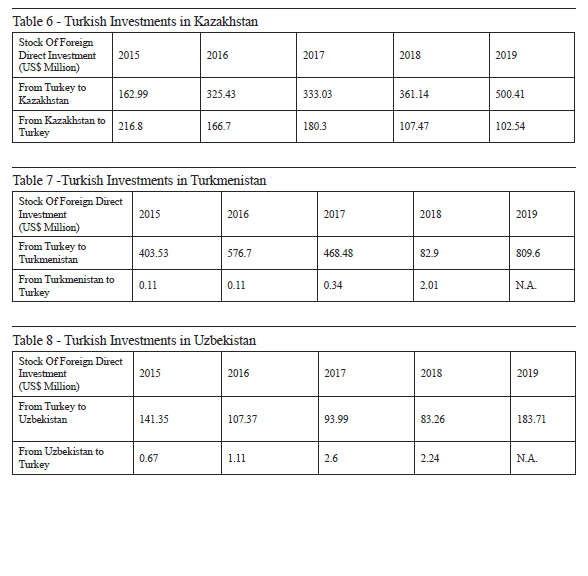

Two major economic areas of cooperation that have grown exponentially between Turkey and the Central Asian republics are trade and investment. As the below tables on trade patterns suggest, Turkey has become an important trade partner to the countries of the region, particularly through its exports, a reflection of the general trend of the country’s expansion of export-oriented industrial production and its growing export share.[59] Turkey’s major exports are machinery, textiles, pharmaceutical equipment, plastics, furniture, and an array of other various manufactured products; its major import items are copper, aluminum, iron, steel, mineral fuels, cotton, agricultural raw resources, food materials, and miscellaneous animal products. However, there is still a long way to go for both Turkey and the republics in attaining full trade potential. Nevertheless, there is an increased commitment among all parties to overcome the barriers related to an increase in trade. In a recent report by the Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEİK) of Turkey, its aim to improve trade relations with the Central Asian republics is highlighted by the inclusion of concrete policies towards this very goal.[60] The Organization of Turkic States provides a multilateral mechanism to facilitate trade between its members through common solutions for major problems such as logistics, transportation, and the possibility of bureaucratic obstacles.[61] Creating a common market for goods, investment, labor, and services in the future is also on the agenda of the parties involved.[62]

Since the early 1990s, economic relations among the Central Asian countries and Turkey have steadily developed. In addition to the various sizes of Turkish business investments in these countries, the content of economic trade is primarily based on exports consisting of processed food, textiles, machinery, transportation equipment, and imports of agricultural raw resources, food materials, steel, iron, and other metals.[63] An overview of data provided in the tables showing trade relations between Turkey and the regional countries indicates a set pattern of relations. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have shared the most economic activity with Turkey in the last 30 years. However, Turkey’s economic relations have remained limited with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Even so, the volume of trade between Turkey and all the regional states has continued to increase, even under the lockdown conditions and travel bans during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

Turkish investment in Central Asia has also grown during this same period. As emphasized above, Turkey’s business sector was positively influenced by the neo-liberal transformation within the country. Such business turned to Central Asia, but also to Eastern Europe while looking for investment opportunities at the end of the Cold War. According to Yıldırım, the Turkish government has promoted investment in Central Asia through certain incentives for Turkish companies’ outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) in the region. There are other factors positively influencing Turkish entrepreneurs’ decisions to invest in Central Asia, such as historical, cultural, and geographical proximity, the region’s vast resources, and the presence of a similar business environment.[64] According to Egresi and Kara, foreign direct investment decisions are never purely economic. Most companies’ choices of a location for investment are determined by cultural factors as culturally closer markets are more favored, compared to unknown markets. Governments are often influential in directing investments from their business sector towards regions they prioritize politically.[65] Cultural proximity, governmental preferences, and a dynamic business sector explain Turkey’s growing investment in Central Asia. The Turkic Business Council, a subsidiary organ of the Organization of Turkic States, is particularly supportive in guiding the business sector to investment opportunities in the region. The food and beverage, iron and steel, textile, and telecommunication sectors are major areas for investment, along with construction, for Turkish companies.[66] There are various major Turkish construction companies that have undertaken several important projects in Central Asia, including infrastructure and superstructure construction, industrial facilities construction, restoration work, and numerous residential projects (see tables below for Turkish investments in Central Asia).[67]

The data accessible through the International Trade Center do not cover the post-2019 period. We assume that this was primarily because of the disruptions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, a closer look at the investment tables shows that Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan occupy the top positions in terms of Turkish investment in Central Asia, a similar pattern to the trade relations data. On the other hand, investments in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are lower in volume, the latter showing the lowest investment rate. It can be claimed that the investment gap in Tajikistan, compared to the other countries, is in line with Egresi and Kara’s argument about the role of cultural proximity in investment decisions.[68]

In terms of Turkish development aid to the region, according to the 2019 Turkish Development Assistance Report published by TİKA, Kyrgyzstan occupied 7th place ($24.12 million) and Kazakhstan, 8th ($22.3 million), in the list of countries benefitting the most from Turkish official development assistance. During the same reporting period, Syria’s development assistance accounted for $7.2 billion.[69] While the amount of aid delivered to the Central Asian countries steadily increased under the JDP, their share in total aid decreased since the Middle East and Africa have since become regions of priority, and due to the breakout of the Syrian civil war.[70]

The post-2002 period can be characterized by the further steps taken toward the institutionalization of regional cooperation. In 2009, at the end of the Ninth Summit of the Heads of Turkic Speaking States, the leaders of Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan signed the Nakchivan Agreement, which established the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States (Turkic Council) as a permanent international organization with headquarters in İstanbul; later, Uzbekistan became a member as well. The organization was later named The Organization of Turkic States in its Eighth Summit in İstanbul. The recent decision of the organization to give observer status to the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is an example of how regional states became more receptive to the soft power diplomacy that Turkey has been following over the years, along with the regional developments favoring Turkey’s position. Historically speaking, Central Asian states were not receptive towards the initial Turkish endeavors to acquire support on the Cyprus issue.[71] The organization is an umbrella one and is affiliated with the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic Speaking Countries (TURKPA-2008), the International Organization of Turkic Culture (TURKSOY-1993), the Turkic World Education and Scientific Cooperation Organization (Turkic Academy-2010), the Turkic Business Council (2011), and the Turkic Culture and Heritage Foundation (2012).[72]

As mentioned before, TRT has been a key player in Turkey’s soft power accession in Central Asia, and this has not abated in the current period. This state radio and television company, which started broadcasting in the region as TRT Eurasia, became TRT Avaz in 2009. Avaz, which means “voice,” is a common word in many Turkic languages. As the name change suggests, TRT Avaz is an inclusive type of project and broadcasts in Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, and Uzbek, with subtitle options in numerous Turkic languages.[73] While there is no data on viewership in Central Asia, this channel and TRT World are considered important tools for Turkey’s soft power strategy in the region. In addition to Turkish TV channels, the development of communication infrastructures has enabled the viewing of private Turkish TV channels through satellites. Over the years, popular Turkish soap operas, documentaries, and various daily programs have enabled constant and close exposure to Turkey, Turkish culture, and Turkish products, which positively contributed to trade and tourism activities.[74] Turkish soap operas are currently being marketed to various areas, from the Former Soviet region to the Middle East, Balkans, South Asia, and Latin America. As an example, Kazakhstan was the first country to which Turkey sold its soap opera “Deliyürek” in 2001.[75] However, at times, authorities in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan banned the broadcast of many Turkish series on their state televisions because of immoral content, or for reasons of cultural protectionism and promotion of national values.[76]

Other projects in different areas continue. The previously mentioned Diyanet supports Turkey’s soft power capabilities by constructing and renovating mosques, as well as providing religious literature in regional languages and in the training of personnel in religious vocational schools and theology centers, either in the region or in Turkey.[77] According to Balcı and Lilles,[78] the Diyanet has managed to “diffuse a Turkish variant of Islam” in the region capable of existing in harmony with state structures.

In the higher education realm, the Directorate of Overseas Turks, and Related Communities (YTB), founded in 2010, became a central organization in overseeing the coordination of higher education grants for Central Asian students along with those from other regions. According to the statistics of the Higher Education Council (YÖK), in the 2020-2021 academic year, the number of students studying in Turkey from Central Asia was as follows: Kazakhstan, 4,857; Kyrgyzstan, 1,766; Turkmenistan, 15,578; Tajikistan, 681; and Uzbekistan, 3,390.[79] While Turkey experienced problems with this program in the beginning, including problems with student selection, a high dropout ratio due to the limited financial means of the chosen students, and adaptation problems, including students’ limited knowledge of Turkish,[80] there has been much improvement since then. The program, which initially only catered to students from Central Asia, is important in that it has pioneered Turkey’s current policy of internationalization of its education to students from a wider geographical area. The YTB also oversees a program that aims to remain in touch with alumni students from the Central Asian region.[81]

In addition to the Turkish government’s official educational activities in the region, there have also been non-state actors from Turkey active in Central Asia since the early 1990s. Two prominent ones that should be mentioned are the Gülen Movement and the Turan Yazgan Turkic World Research Foundation. Both have been operating elementary, secondary, and high schools and higher education institutions abroad, albeit the latter’s activities are more limited. While the Foundation has a more pan-Turkic character and provides secular education, the Gülen Movement belongs to the Nurcu school of Islam and emphasizes the Islamic teachings of this tradition. The Gülen Movement and its schools were prevalent in almost all Central Asian countries except for Uzbekistan, which closed all Gülen schools in 1999; Turkmenistan did the same in 2011.[82] The Gülen schools’ preeminent position in Central Asia diminished quite sharply after the July 15th events in Turkey, after which the JDP requested that all Gülen schools be closed in various parts of the world, including Central Asia. Kazakhstan and Tajikistan agreed to close them, while Kyrgyzstan did not. However, the name was changed and the schools’ status was negatively affected there, with the schools being put under strict surveillance.[83]

The Maarif Foundation was established as Turkey’s official overseas educational foundation in 2016 as a soft power tool to reduce the influence of Gülen schools abroad, including in the Central Asian region.[84] Finally, the Yunus Emre Foundation, which has been active since 2009 and aims to introduce the Turkish language and culture to foreigners through Turkish Cultural Centers, is a relatively recent soft power component. In Central Asia, there is currently only one Center operating in Kazakhstan’s capital, Nur-Sultan.

It should be noted that Turkey’s relations with each republic did not always follow a linear progress and faced challenges, leading to the slowing down—even stagnation—of relations. This is mostly due to domestic factors and leadership perceptions regarding Turkey’s role and intentions vis-à-vis each republic. Central Asian leaders established one-man regimes, gradually consolidating their power by eliminating the opposition and by other means. All of the first presidents, except for Kyrgyzstan’s Askar Akaev, were part of the Soviet political nomenclature before independence. Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev, Uzbekistan’s Islam Karimov, and Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov strengthened their hold on power by gradually eliminating the opposition; Tajikistan’s president, Emomali Rakhmon, was able to confirm his incumbency after the end of the country’s bloody civil war in 1997. Kyrgyzstan’s Askar Akaev, despite his initial promises about a rapid democratization of the country, also solidified his position through various institutional changes. However, he was ousted from power in 2005 as a result of widespread popular protests and the opposition’s claims that Akaev had rigged parliamentary elections.[85] Kyrgyzstan is unique in terms of the frequent shuffling at the top leadership level as the country would go through a change of leadership three more times as a result of popular discontent. [86] In Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan the transition of political power came as a result of Niyazov and Karimov’s deaths and Nazarbayev’s resignation; these three leaders had established a very firm grip on power and steadily eliminated all opposition forces.[87]

As the top leadership levels are quite dominant in foreign policy decision-making in Central Asia, the perceptions of the presidents are very influential in the foreign policy trajectories they have pursued. For example, during the first years of post-independence, Uzbekistan-Turkey relations were very close, but they soured after Turkey provided a safe haven to the Uzbek opposition leader Muhammed Salih in 1993. President Karimov’s wary attitude about Turkey’s intentions led to a stagnation of relations between the two countries for almost two decades. Only after Karimov’s death, with Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s ascension to power in 2016, did relations begin to improve with renewed vigor in multiple areas.[88]

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent independence of the Central Asian republics encouraged Turkish foreign policymakers to develop new foreign policy principles and priorities. These were characterized by an increase in relations with the new geography using soft power through economic and cultural outreach, and Central Asia has provided Turkish policymakers with a fertile ground to use these new soft power foreign policy tools. The increase in diplomatic, economic, political, social, and cultural contacts has resulted in developing additional, comprehensive, and specific policy choices over time. Initially shaped after the Cold War, Turkish foreign policy towards Central Asia has evolved since then. Between 1991 and 1992, both the benefactor and recipient exhibited overenthusiastic and ambitious agendas in the initial phase.

As part of the post-Cold War period transformation, Turkey’s foreign policy direction evolved more around soft power tools. The country has increasingly emphasized its economic and commercial links with many parts of the world, including Central Asia. Today, there are intense networks and links between the two, mainly in the economic, commercial, and energy sectors, and culture and education are the soft power tools used in Turkey’s relations with the Central Asian states. Official institutions such as TİKA, TRT, the Diyanet, and various educational institutions are active in the region and contribute to the increasing cultural links between Turkey and its Turkic neighbors.

While Turkey is often depicted in the literature and official and popular sources as a regional actor currently capable of using its soft power capacity, the use of soft power assets and the geopolitical vision for a cooperative Turkic region actually began with the formulation of Turkish foreign policy towards Central Asia after the Cold War. During the initial years, regional leadership aspirations might have overshadowed those policies; however, more recently, the increasing application of soft power strategies has resulted in the emergence of a pragmatic foreign policy approach supported by contextual realities and motivated by economic interests.

Notes

[1] Mustafa Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya ile İlişkiler,” in Türk Dış Politikası: Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar, ed. Baskın Oran (İstanbul, Turkey: İletişim Yayınları, vol. II, 12. ed., 2010), 366–439.

[2] Bülent Gökay, Turkey in the Global Economy: Neoliberalism, Global Shift and Making of a Rising Power (Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

[3] Björn Hettne, Andras Inotai and Osvaldo Sunkel, The New Regionalism and the Future of Security and Development (New York City, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2000) xviii-xxxii; Stephen Calleya, Regionalism in the Post-Cold War World (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2000); Richard Rosecrance, “Regionalism and the Post-Cold War Era,” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 46, no. 3 (1991): 373-393.

[4] Robert O. Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984).

[5] Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Soft Power,” Foreign Policy, Autumn, no. 80 (1990): 153–171.

[6] Ibid., 154.

[7] Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Get Smart: Combining Hard and Soft Power,” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (2009): 160-163

[8] Ibid.,161.

[9] Ying Fan, “Soft Power: Power of Attraction or Confusion?” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 4, no. 2 (2008): 147–158.

[10] Nye, Jr., “Get Smart,” 162.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Sanem Çevik, “Reassessing Turkey’s Soft Power: The Rules of Attraction,” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 44, no.1 (2019): 53.

[13] Haluk Karadağ, “Forcing the Common Good: The Significance of Public Diplomacy in Military Affairs,” Armed Forces & Society, 43, no.1 (2017): 72–91.

[14] Alper Kaliber, “The Post-Cold War Regionalisms of Turkish Foreign Policy,” Journal of Regional Security 8, no.1 (2013): 25-48.

[15] Pınar Bilgin and Ali Bilgiç, “Turkey’s New Foreign Policy towards Eurasia,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 52, no.2 (2011): 191.

[16] Murat Yeşiltaş, “Transformation of the Geopolitical Vision in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Turkish Studies 14, no.4 (2013): 668.

[17] Ibid., 673-674.

[18] Mustafa Türkeş, “Decomposing Neo-Ottoman Hegemony,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 18, no.3 (2016): 199–200.

[19] Kaliber, “The Post-Cold,” 33.

[20] Çevik, “Reassessing Turkey’s,” 55.

[21] Tarık Oğuzlu, “Soft Power in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 61, no.1 (2007): 81–97; Meliha B. Altunışık, “The Possibilities and Limits of Turkey’s Soft Power in the Middle East,” Insight Turkey 10, no.2 (2008): 41–54; İbrahim Kalın, “Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Turkey,” Perceptions 16, no. 3 (2011): 5–23; Hakan Ö. Ongur, “Identifying Ottomanisms: The Discursive Evolution of Ottoman Pasts in the Turkish Presents,” Middle Eastern Studies 51, no.3 (2015): 416–432; Umut Kedikli and Önder Çalağan, “Orta Asya’ya Yönelik Bir Yumuşak Güç Unsuru Olarak Kültür Politikaları,” paper presented at 15. Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Sosyal Bilimler Kongresi Tebliğleri, İstanbul, TR, 2017, 655-670.

[22] Mustafa Kutlay and Ziya Öniş, “Turkish Foreign Policy in a Post-Western Order: Strategic Autonomy or New Forms of Dependence?” International Affairs 97, no.4 (2021): 1104.

[23] Abdullah Gündoğdu and Cafer Güler, “Kazakistan’ın Bağımsızlığının Tanınma Süreci ve Türk Kamuoyundaki Yankıları,” A.Ü. Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi 36, no.61 (2017): 80–82.

[24] Mustafa Aydın, “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya ve Kafkaslar Politikası,” in Küresel Politikada Orta Asya (Avrasya Üçlemesi I), ed. Mustafa Aydın, (Ankara, Turkey: Nobel Yayınları, 2005); Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya ile İlişkiler”

[25] Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya ile İlişkiler.”

[26] Ibid.; Philip Robins, Suits and Uniforms: Turkish Foreign Policy Since the Cold War, (London, UK: Hurst and Company, 2003)

[27] Ibid.

[28] Mustafa Aydın, “Foucault's Pendulum: Turkey in Central Asia and the Caucasus,” Turkish Studies 5, no.2 (2004): 1–22.

[29] Andrew Mango, “The Turkish Model,” Middle Eastern Studies 29, no.4 (1993): 726.

[30] Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya.”

[31]It should be noted that in terms of Turkish foreign policy-making, Azerbaijan has often been grouped with the Turkic republics of Central Asia, although it is not located in the region. This is because Azerbaijan has always had a unique place in Turkish foreign policy due to its closer historical, linguistic, and cultural ties with Turkey. Over the years, the relations between the two have grown exponentially in various fields, except for the crisis periods over negotiations on bilateral gas deals and Turkey’s rapprochement politics with Armenia in 2008-2010.

[32] Ibid.; Gündoğdu and Güler, “Kazakistan’ın Bağımsızlığının.”

[33] Mustafa Durmuş and Harun Yılmaz, “Son Yirmi Yılda Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’ya Yönelik Dış Politikası ve Bölgedeki Faaliyetleri,” in Bağımsızlıklarının Yirminci Yılında Orta Asya Cumhuriyetleri Türk Dilli Halklar-Türkiye ile İlişkileri, ed. Ayşegül Aydıngün and Çiğdem Balım (Ankara, Turkey: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayınları, 2012), 492.

[34] “Nazarbayev Memnun Ayrıldı,” Milliyet, 30 September 1991.

[35] Aydın, “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya.”

[36] Emel Parlar-Dal and Emre Erşen, “Reassessing the ‘Turkish Model’ in the Post- Cold War Era: A Role Theory Perspective,” Turkish Studies 15, no.2 (2014): 258-282.

[37] Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya.”

[38] Hakan Fidan, “Turkish Foreign Policy towards Central Asia,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 12, no. 1 (2010): 113.

[39] Turgut Demirtepe and Güner Özkan, “Transformation of a Development Aid Agency: TİKA in a Changing Domestic and International Setting,” Turkish Studies 13, no.4 (2012): 647-664.

[40] Pınar İpek, “Ideas and Change in Foreign Policy Instruments: Soft Power and the Case of the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency,” Foreign Policy Analysis 11, no.2 (2015): 180.

[41] Robins, Suits, and Uniforms, 285-308.

[42] Aydın, “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya ile İlişkiler.”

[43] Stephen Larrabee, “Turkey’s Eurasia Agenda,” The Washington Quarterly 34, no.1 (2011): 103-120.

[44] Mert Bilgin, “Türkiye’nin İhracata Yönelik Politikalarında Avrasya’nın Önemi,” in Türkiye’nin Avrasya Macerası 1989-2006, ed. Mustafa Aydın, (Ankara, Turkey: Nobel Yayınları, 2007), 73-81.

[45] Aidarbek Amirbek, Almasbek Anuarbekuly, and Kanat Makhanov, “Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Entegrasyonu: Tarihsel Gelişimi ve Kurumsallaşması,” ANKASAM: Bölgesel Araştırmalar Dergisi 1, no.3 (2017): 164-204.

[46] Bayram Balcı, “Turkey’s Religious Outreach in Central Asia and the Caucasus,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 16 (2014): 70.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.; Burak Gümüş, “Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı’nın Orta Asya’daki Faaliyetleri,” Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Dergisi 2, no.1 (2010): 5.

[49] Murat Özoğlu, Bekir Gür, and İpek Coşkun, Küresel Eğilimler Işığında Türkiye’de Uluslararası Öğrenciler, (Ankara, Turkey: Seta Yayınları, 2012): 58.

[50] Cennet Engin-Demir and Pınar Akçalı, “Turkey’s Educational Policies in Central Asia and Caucasia: Perceptions of Policy Makers and Experts,” International Journal of Educational Development 32, no.1 (2012): 12.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Turkish Ministry of National Education - MEB, Formal Education 2014/15 Statistics, (Ankara, Turkey: Turkish Ministry of National Education MEB Publications, 2016).

[53] Engin-Demir and Akçalı, “Turkey’s Educational,” 12.

[54] “Turkey’s Relations with Central Asian Republics,” Ministry of Turkish Foreign Affairs, April 10, 2020. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye_s-relations-with-central-asian-republics.en.mfa.

[55] Bilgin and Bilgiç, “Turkey’s New Foreign,” 187.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Yaşar Sarı, “Türkiye-Orta Asya İlişkilerinde Sınırlı İşbirliği,” in Ak Partinin 15 Yılı: Dış Politika, ed. Kemal İnat,, Ali Aslan, and Burhanettin Duran (İstanbul, Turkey: Seta Yayınları 2017): 359.

[58] Gökay, Turkey in the Global.

[59] Prepared by the authors based on the data retrieved from International Trade Centre at https://www.trademap.org (accessed on 19 December 2022).

[60] The Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey – DEİK, “Turkey-Eurasia: Outward Foreign Direct Investments,” DEİK, May 15, 2020. https://deik.org.tr/uploads/avrasya-sekorel-rapor-revize-yenisi-min.pdf.

[61]Azimzhan Khitakhunov, “Trade between Turkey and Central Asia,” Eurasian Research Institute, February, 2021. https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/trade-between-turkey-and-central-asia/.

[62]“Turkey Reaches out to Central Asia,” Geopolitical Futures, March 12, 2021. https://geopoliticalfutures.com/turkey-reaches-out-to-central-asia/

[63] Mustafa Şen, “Türkiye-Orta Asya Yatırım İlişkileri ve Bölgede Aktif Türk Girişimciler,” in Türkiye’nin Avrasya Macerası 1989-2006, ed. Mustafa Aydın, (İstanbul, Turkey: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım, 2007): 109-142.

[64] Canan Yildirim, “Turkey’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Trends and Patterns of Mergers and Acquisitions,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 19, no.3 (2017): 280.

[65] Istvan Egresi and Fatih Kara, “Foreign Policy Influences on Outward Direct Investment: The Case of Turkey,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 17, no.2 (2015): 182-187.

[66] Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey – DEİK, “Outbound Investment Index 2019,” DEİK, 2020. https://www.deik.org.tr/events-outbound-investments-index-2019-press-conference.

[67] “Tables are prepared by the authors based on the data retrieved from International Trade Centre,” https://www.investmentmap.org/investment/time-series-by-country (accessed on 19 November 2021).

[68] Istvan Egresi and Fatih Kara, “Foreign Policy Influences on Outward Direct Investment: The Case of Turkey,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 17, no.2 (2015): 182-187.

[69] Türk İşbirliği ve Koordinasyon Ajansı Başkanlığı – TİKA, “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2019,” TİKA, 2020. https://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/sayfa/publication/2019/TurkiyeKalkinma2019WebENG.pdf.

[70] Baha A. Yılmaz, “Soğuk Savaş Sonrası Dönemde Türk-Orta Asya İlişkilerinde Türk Keneşi’nin Rolü: Dönemler ve Değişim Dinamikleri,” Barış Araştırmaları ve Çatışma Çözümleri Dergisi 7, no.1 (2019): 21-2; Nuri Yılmaz and Gökmen Kılıçoğlu, “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’daki Yumuşak Gücü ve Kamu Diplomasisi Uygulamalarının Analizi,” Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları 119, no.235 (2018):156.

[71] See: Durmuş and Yılmaz, “Son Yirmi Yılda Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’ya Yönelik Dış Politikası” 493; Fidan, “Turkish Foreign Policy,” 116.

[72] Kürşad M. Sarıarslan, “Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Parlamenter Asamblesi (TÜRKPA),” in Türk Cumhuriyetleri ve Topluluğu Yıllığı 2013, ed. Murat Yılmaz and Turgut Demirtepe, (Ankara: Hoca Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015), 589-593; Darhan Kıdırali, “Türk Konseyi (Türk Keneşi),” in Türk Cumhuriyetleri ve Topluluğu Yıllığı 2013, ed. Murat Yılmaz and Turgut Demirtepe, (Ankara, Turkey: Hoca Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015), 576-589.

[73] Fatma Kelkitli, “The Meeting of the Crescent and the Dragon: Post-Cold War Sino-Turkish Rivalry and Cooperation in Central Asia and the Middle East,” OAKA Dergisi 9, no.17 (2014): 163.

[74] Niyazi Gümüş, Gülzira Zhaxyglova, and Maiya Mirzabekova, “Using Turkish Soap Operas (Tv Series) As A Marketing Communication Tool: A Research on Turkish Soap Operas in Kazakhstan,” International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences 8, no.26 (2017): 390-407.

[75] Serpil Karlıdağ and Selda Bulut, “The Transnational Spread of Turkish Television Soap Operas,” İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Dergisi 47, no.2 (2014): 75-96.

[76] Kanykei Tursunbayeva, “Central Asia’s Rulers View Turkish ‘Soap Operas’ with Suspicion,” Global Voices, August 7, 2014. https://globalvoices.org/2014/08/07/central-asias-rulers-view-turkish-soap-power-with-suspicion/; “No Turkish Soaps Please, We’re Uzbek,” Eurasianet, June 20, 2019. https://eurasianet.org/no-turkish-soaps-please-were-uzbek.

[77] Yılmaz and Kılıçoğlu, “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’daki”.

[78] Bayram Balcı and Thomas Liles, “The Struggle over Central Asia Chinese-Russian Rivalry and Turkey’s Comeback,” Insight Turkey 20, no.4, (2018): 21.

[79] Turkish Higher Board of Education, “Statistics on Foreign Students,” https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr, (accessed date December 21, 2022). The reason for the number of Turkmen students being much higher is that most of these students mainly come to Turkey for work with a student visa, which is much easier to receive and enables them to stay for longer periods (Rustomjon Urinboyev and Sherzod Eraliev, The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian Migrant Workers in Russia and Turkey, (New York City, NY: Springer, 2022).

[80] Yüksel Kavak and Gülsun A. Baskan, “Türkiye’nin Türk Cumhuriyetleri, Türk ve Akraba Topluluklarına Yönelik Eğitim Politika ve Uygulamaları,” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 20, no. 20 (2001): 92-103.

[81] Yılmaz and Kılıçoğlu, “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’daki,” 168.

[82] Balcı and Liles, “The Struggle Over,” 24.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Çevik, “Reassessing Turkey’s Soft,” 57.

[85] Valery Bunce and Sharon L. Wolchik, Defeating Authoritatian Leaders in Post-Communist Countries (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[86] Asel Doolotkeldieva, “The 2020 Violent Change in Government in Kyrgyzstan amid the Covid-19 Pandemic: Three Distinct Stories in One,” in Between Peace and Conflict in the East and the West, ed. Anja Mihr, (New York City, NY: Springer, 2021), 157-174.

[87] Nur Çetin, “Central Asian States’ Relations with Turkey (1991-2020),” in The Changing Perspectives of Central Asia in the 21st Century, ed. Murat Yorulmaz and Serdar Yılmaz, (İstanbul, Turkey: Kriter Yayınları, 2020), 147-169.

[88] Fatima Taşkömür, “How Did Turkey-Uzbek Relations Improved after two decades of Stagnation?” TRT World, October 26, 2017. https://www.trtworld.com/turkey/how-did-turkey-uzbek-relations-improve-after-two-decades-of-stagnation--11677.

Altunışık, Meliha B. “The Possibilities and Limits of Turkey’s Soft Power in the Middle East.” Insight Turkey 10, no.2 (2008): 41–54.

Amirbek, Aidarbek, Almasbek Anuarbekuly, and Kanat Makhanov. “Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Entegrasyonu: Tarihsel Gelişimi ve Kurumsallaşması [Turkic Speaking Countries' Integration: Its Historical Development and Institutionalization]." ANKASAM: Bölgesel Araştırmalar Dergisi 1, no. 3 (2017): 164-204.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Foucault’s Pendulum: Turkey in Central Asia and the Caucasus.” Turkish Studies 5, no.2 (2004): 1–22.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Kafkasya ve Orta Asya ile İlişkiler [Relations with the Caucasus and Central Asia].”In Türk Dış Politikası: Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar [Turkish Foreign Policy: Facts, Documents, and Comments from the War of Independence to the Present], ed. Baskın Oran, 366-439. İstanbul, Turkey: İletişim Yayınları, vol. II, 12. ed., 2010.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Türkiye'nin Orta Asya ve Kafkaslar Politikası [Turkey's Policy on Central Asia and the Caucasus]." In Küresel Politikada Orta Asya (Avrasya Üçlemesi I) [Central Asia in Global Politics (Eurasia Trilogy I), ed. Mustafa Aydın, 101-149. Ankara, Turkey: Nobel Yayınları, 2005. Balcı, Bayram, and Thomas Liles. “The Struggle over Central Asia Chinese-Russian Rivalry and Turkey’s Comeback.” Insight Turkey 20, no.4, (2018): 11-27.

Balcı, Bayram, and Thomas Liles. “Turkey’s Religious Outreach in Central Asia and the Caucasus.” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 16 (2014): 65-85.

Bilgin, Mert. "Türkiye’nin İhracata Yönelik Politikalarında Avrasya’nın Önemi [The Importance of Eurasia in Turkey's Export-Oriented Policies]." In Türkiye’nin Avrasya Macerası 1989-2006 [Turkey's Eurasian Adventure 1989-2006], ed. Mustafa Aydın, 73-81. Ankara, Turkey: Nobel Yayınları, 2007.

Bilgin, Pınar, and Ali Bilgiç. “Turkey’s New Foreign Policy towards Eurasia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 52, no.2 (2011): 173-195.

Bunce, Valery, and Sharon L. Wolchik. Defeating Authoritarian Leaders in Post-Communist Countries. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011. Calleya, Stephen. Regionalism in the Post-Cold War World. Aldershot, United Kingdom: Ashgate, 2000.

Çetin, Nur. “Central Asian States’ Relations with Turkey (1991-2020).” In The Changing Perspectives of Central Asia in the 21st Century, edited by Murat Yorulmaz, and Serdar Yılmaz, 147-169. İstanbul, Turkey: Kriter Yayınları, 2020.

Çevik, Sanem, “Reassessing Turkey’s Soft Power: The Rules of Attraction.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 44, no.1 (2019): 50-71.

Demirtepe. Turgut and Güner Özkan. “Transformation of a Development Aid Agency: TİKA in a Changing Domestic and International Setting.” Turkish Studies 13, no.4 (2012): 647-664.

Doolotkeldieva, Asel. “The 2020 Violent Change in Government in Kyrgyzstan amid the Covid-19 Pandemic: Three Distinct Stories in One.” In Between Peace and Conflict in the East and the West, edited by Anja Mihr, 157-174. (New York City, NY: Springer, 2021.

Durmuş Mustafa, and Harun Yılmaz. “Son Yirmi Yılda Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’ya Yönelik Dış Politikası ve Bölgedeki Faaliyetleri [Turkey's Foreign Policy towards Central Asia in the Last Twenty Years and Activities]." in Bağımsızlıklarının Yirminci Yılında Orta Asya Cumhuriyetleri Türk Dilli Halklar-Türkiye ile İlişkileri [Central Asian Republics in the Twentieth Year of Their Independence, Turkic Speaking Peoples-Relations with Turkey], ed. Ayşegül Aydıngün and Çiğdem Balım, 483-587. Ankara, Turkey: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Yayınları, 2012.

Egresi, Istvan, and Fatih Kara. “Foreign Policy Influences on Outward Direct Investment: The Case of Turkey.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 17, no.2 (2015): 181-203.

Engin-Demir, Cennet and Pınar Akçalı. “Turkey’s Educational Policies in Central Asia and Caucasia: Perceptions of Policy Makers and Experts.” International Journal of Educational Development 32, no.1 (2012): 11-21.

Fan, Ying. “Soft Power: Power of Attraction or Confusion?” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 4, no. 2 (2008): 147–158.

Fidan, Hakan. “Turkish Foreign Policy towards Central Asia.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 12, no: 1 (2010): 109-121.

Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey – DEİK. “Outbound Investment Index 2019.” DEİK. 2020. https://www.deik.org.tr/events-outbound-investments-index-2019-press-conference.

Gökay, Bülent. Turkey in the Global Economy: Neoliberalism, Global Shift and Making of a Rising Power. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021.

Gümüş, Burak. "Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı’nın Orta Asya’daki Faaliyetleri [Activities of the Directorate of Religious Affairs in Central Asia]." Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Dergisi 2, no. 1 (2010): 1-8.

Gümüş, Niyazi, Gülzira Zhaxyglova, and Maiya Mirzabekova. “Using Turkish Soap Operas (Tv Series) As A Marketing Communication Tool: A Research on Turkish Soap Operas in Kazakhstan.” International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences 8, no.26 (2017): 390-407.

Gündoğdu, Abdullah, and Cafer Güler. “Kazakistan’ın Bağımsızlığının Tanınma Süreci ve Türk Kamuoyundaki Yankıları [The Recognition Process of Kazakhstan's Independence and Its Repercussions in the Turkish Public].” A.Ü. Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi 36, no.61 (2017): 75-94.

Hettne, Björn, Andras Inotai, and Osvaldo Sunkel. The New Regionalism and the Future of Security and Development. New York City, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

İpek, Pınar. “Ideas and Change in Foreign Policy Instruments: Soft Power and the Case of the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency.” Foreign Policy Analysis 11, no.2 (2015): 173-193.

Kaliber, Alper. “The Post-Cold War Regionalisms of Turkish Foreign Policy.” Journal of Regional Security 8, no.1 (2013): 25-48.

Kalın, İbrahim. “Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Turkey.” Perceptions 16, no. 3 (2011): 5-23.

Karadağ, Haluk. “Forcing the Common Good: The Significance of Public Diplomacy in Military Affairs.” Armed Forces & Society, 43, no.1 (2017): 72–91.

Karlıdağ, Serpil, and Selda Bulut. “The Transnational Spread of Turkish Television Soap Operas.” İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Dergisi 47, no.2 (2014): 75-96.

Kavak, Yüksel, and Gülsun A. Baskan. “Türkiye’nin Türk Cumhuriyetleri, Türk ve Akraba Topluluklarına Yönelik Eğitim Politika ve Uygulamaları [Training for Turkic Republics, Turkish and Related Communities of Turkey Politics and Practices]." Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 20, no. 20 (2001): 92-103.

Kedikli Umut, and Önder Çalağan. "Orta Asya'ya Yönelik Bir Yumuşak Güç Unsuru Olarak Kültür Politikaları [Cultural Policies as a Soft Power Element towards Central Asia]." Paper presented at 15. Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Sosyal Bilimler Kongresi Tebliğleri [Proceedings of the 15th International Turkic World Social Sciences Congress], İstanbul, Turkey, 2017, 655-670.

Kelkitli, Fatma A. “The Meeting of the Crescent and the Dragon: Post-Cold War Sino-Turkish Rivalry and Cooperation in Central Asia and the Middle East.” OAKA Dergisi 9, no.17 (2014): 149-178.

Keohane, Robert O. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Khitakhunov, Azimzhan. “Trade between Turkey and Central Asia.” Eurasian Research Institute. February, 2021. https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/trade-between-turkey-and-central-asia/.

Kıdırali, Darhan. “Türk Konseyi (Türk Keneşi) [Turkic Council]." In Türk Cumhuriyetleri ve Topluluğu Yıllığı 2013 [Turkic Republics and Community Yearbook 2013] , ed. Murat Yılmaz and Turgut Demirtepe, 576-589. Ankara: Hoca Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015.

Kutlay, Mustafa, and Ziya Öniş. “Turkish Foreign Policy in a Post-Western Order: Strategic Autonomy or New Forms of Dependence?” International Affairs 97, no.4 (2021): 1085-1104.

Larrabee, Stephen. “Turkey’s Eurasia Agenda.” The Washington Quarterly 34, no.1 (2011): 103-120.

Mango, Andrew. “The Turkish Model.” Middle Eastern Studies 29, no.4 (1993): 726-757.

“Nazarbayev Memnun Ayrıldı [Nazarbayev Departed with Satisfaction].” Milliyet. September 30, 1991.

“No Turkish Soaps Please, We’re Uzbek.” Eurasianet. June 20, 2019. https://eurasianet.org/no-turkish-soapsplease-were-uzbek.

Nye Jr., Joseph S. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy, Autumn, no. 80 (1990): 153–171.

Nye Jr., Joseph S. “Get Smart: Combining Hard and Soft Power.” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (2009): 160-163

Oğuzlu, Tarık. “Soft Power in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 61, no.1 (2007): 81–97.

Ongur, Hakan Ö. “Identifying Ottomanisms: The Discursive Evolution of Ottoman Pasts in the Turkish Presents.” Middle Eastern Studies 51, no.3 (2015): 416–432.

Özoğlu, Murat, Bekir Gür, and İpek Coşkun. Küresel Eğilimler Işığında Türkiye’de Uluslararası Öğrenciler [International Students in Turkey in Light of Global Trends]. Ankara, Turkey: Seta Yayınları, 2012.

Parlar-Dal, Emel, and Emre Erşen. “Reassessing the ‘Turkish Model’ in the Post-Cold War Era: A Role Theory Perspective.” Turkish Studies 15, no.2 (2014): 258-282.

Robins, Philip. Suits and Uniforms: Turkish Foreign Policy Since the Cold War. London United Kingdom: Hurst and Company, 2003.

Rosecrance, Richard. “Regionalism and the Post-Cold War Era.” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 46, no. 3 (1991): 373-393.

Sarı, Yaşar. “Türkiye-Orta Asya İlişkilerinde Sınırlı İşbirliği [Limited Cooperation in Turkey-Central Asian Relations].” In Ak Partinin 15 Yılı: Dış Politika [15 Years of the AK Party: Foreign Policy], ed. Kemal İnat, Ali Aslan, ve Burhanettin Duran, 357-381. İstanbul, Turkey: Seta Yayınları 2017.

Sarıarslan, Kürşad M. “Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Parlamenter Asamblesi (TÜRKPA) [Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic Speaking Countries (TÜRKPA)]." In Türk Cumhuriyetleri ve Topluluğu Yıllığı 2013 [Turkic Republics and Community Yearbook 2013], ed. Murat Yılmaz and Turgut Demirtepe, 589-593. Ankara: Hoca Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015.

Şen, Mustafa. “Türkiye-Orta Asya Yatırım İlişkileri ve Bölgede Aktif Türk Girişimciler [Turkey-Central Asia Investment Relations and Turkish Entrepreneurs Active in the Region]." In Türkiye’nin Avrasya Macerası 1989-2006 [Turkey's Eurasian Adventure 1989-2006], ed. Mustafa Aydın, 109-141. İstanbul, Turkey: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım, 2007.

Taşkömür, Fatima. “How Did Turkey-Uzbek Relations Improved after two decades of Stagnation?” TRT World. October 26, 2017. https://www.trtworld.com/turkey/how-did-turkey-uzbek-relations-improve-after-twodecades-of-stagnation--11677.

The Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey – DEİK. “Turkey-Eurasia: Outward Foreign Direct Investments.” DEİK. May 15, 2020. https://deik.org.tr/uploads/avrasya-sekorel-rapor-revize-yenisi-min.pdf.

Türkeş, Mustafa. “Decomposing Neo-Ottoman Hegemony.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 18, no.3 (2016): 191–216.

“Turkey Reaches out to Central Asia. Geopolitical Futures.” March 12, 2021. https://geopoliticalfutures.com/turkeyreaches-out-to-central-asia/.

“Turkey’s Relations with Central Asian Republics.” Ministry of Turkish Foreign Affairs. April 10, 2020. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye_s-relations-with-central-asian-republics.en.mfa.

Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency – TİKA. “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2019.” TİKA. 2020. https://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/sayfa/publication/2019/TurkiyeKalkinma2019WebENG.pdf.

Turkish Higher Board of Education - YÖK. “Statistics on Foreign Students.” YÖK. https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr, (access date December 21, 2022).

Turkish Ministry of National Education - MEB. Formal Education 2014/15 Statistics. Ankara, Turkey: Turkish Ministry of National Education MEB Publications, 2016.

Tursunbayeva, Kanykei. “Central Asia’s Rulers View Turkish ‘Soap Operas’ with Suspicion.” Global Voices. August 7, 2014. https://globalvoices.org/2014/08/07/central-asias-rulers-view-turkish-soap-power-with-suspicion/.

Urinboyev, Rustomjon, and Sherzod Eraliev. The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian Migrant Workers in Russia and Turkey. New York City, New York: Springer, 2022.

Yeşiltaş, Murat. “Transformation of the Geopolitical Vision in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Turkish Studies 14, no.4 (2013): 661-687.

Yildirim, Canan. “Turkey’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Trends and Patterns of Mergers and Acquisitions.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 19, no.3 (2017): 276-293.

Yılmaz, Baha A. “Soğuk Savaş Sonrası Dönemde Türk-Orta Asya İlişkilerinde Türk Keneşi’nin Rolü: Dönemler ve Değişim Dinamikleri [The Role of the Turkic Council in Turkish-Central Asian Relations in the Post-Cold War Period: Periods and Change Dynamics]." Barış Araştırmaları ve Çatışma Çözümleri Dergisi 7, no. 1 (2019): 1-25.

Yılmaz, Nuri, and Gökmen Kılıçoğlu. “Türkiye’nin Orta Asya’daki Yumuşak Gücü ve Kamu Diplomasisi Uygulamalarının Analizi [Analysis of Turkey's Soft Power and Public Diplomacy Practices in Central Asia]." Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları 119, no. 235 (2018): 141-184.