Cem Savaş, Yeditepe University

This study aims to present a critical portrayal of teaching geopolitics at Turkish universities by assessing both undergraduate and graduate levels of Political Science and International Relations (IR) curricula. Geopolitical analysis has gone through several phases and traditions by conceiving space as a crucial element for representing world politics. In addition to interstate rivalries, geopolitics also refers to many conflicts and rivalries within an intrastate framework in the context of multiple territorial scales. While geopolitics seems to be falsely perceived as something equal to a state-centric and hard realist academic subfield under a strong military tutelage in Turkey, it lacks a broad multi-level analysis, as well as geographical and historical reasoning. In this study, I propose to consider cartography, territoriality, and geopolitical representations, which form the basis of contemporary geopolitical analysis. The article evaluates weekly schedules, learning outcomes, content, and objectives of the courses available on the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) information packages on university websites. Based on a qualitative case study, it eventually aims to improve the methodological character of geopolitics teaching, indirectly influencing the level and quality of geopolitics in Turkey.

Geopolitics has become a very popular, fuzzy, and even a clichéd concept in some ways as we are talking about the “geopolitics of taste”, “geopolitics of gastronomy” or “geopolitics of football” in our daily lives.[i] First of all, geopolitics is concerned with issues of influence and authority over geographical areas. It employs geographical structures to make sense of global events. Therefore, it studies the relationship between geography and politics; and it reflects geographical frames to make sense of world affairs.[ii] As a field of study, geopolitics has no agreed “home” field being located somewhere between geography, IR, and other social sciences such as sociology and economy. In geopolitics, we study international politics but keep a geographical vision, and a territorial approach, which is the main difference between IR and geopolitics.

When using the word “geopolitics”, we usually discuss IR-related issues. However, geopolitics also represents a method of context analysis based on a geographical and historical approach. In this paper, I approach geopolitics as a reliable comprehensive method of analyzing international relations. Geographical reasoning shows itself at different levels of analysis and on the intersections of multiple spatial assemblies while historical reasoning integrates the past and the present.[iii] According to French geographer Yves Lacoste, geopolitics is especially concerned with the “study of power rivalries over a territory (...); and the capacity of a power to project itself outside this territory”.[iv] In this direction, this study aims to present a critical portrayal of teaching geopolitics at Turkish universities by assessing both undergraduate and graduate levels of Political Science and IR curricula. As a main research question, geopolitics remains above all a method. More specifically, the paper deals with how the teaching of geopolitics in Turkey represents an exemplary case in which geopolitics is not apprehended from a methodological point of view at all.

This paper relies on the case study methodology which is one of the verification strategies in social sciences based on an empirical research strategy.[v] The case study further promotes the use of document analysis for data collection.[vi] Even if the case study does not make it possible to generalize easily, on the other hand, it promotes a more in-depth analysis of a given phenomenon.[vii] It also represents one of the techniques of qualitative analysis in the social sciences.[viii] It is the most widely used data-gathering instrument and verification strategy.[ix] This study collected and classified the data of ECTS packages, and online documents listed on the websites of Turkish universities. From ECTS data as objective measurement instruments, I argue that they represent a certain reliability since they have an exemplary capacity to faithfully measure a phenomenon.[x] As a researcher, I consulted these documents from which I extracted factual information or opinions that will be used to support my argument in this work.[xi]

In the following section, I first assess how and in which contexts the conceptual framework of geopolitics has developed as a distinct field of study. Then, in the third section, I analyze geopolitics as a critical method in terms of representations, spatial levels of analysis, and cartography. In the final section, I depict the current situation of geopolitics teaching in Turkey by evaluating the courses available on the ECTS information packages on Turkish university websites. In this context, the article examines the qualitative ECTS data (course name, purpose and content, and if any, 14-week program information) including the courses related to geopolitics in many “Political Science and IR/IR” departments in Turkey.

As a mainstream approach, geopolitics is concerned with how geographical factors such as territories, people, location, and natural resources influence political outcomes. As Colin Gray outlines, one can refer to the central idea of inescapable geography.[xii] Geography seems to be out there, physically, as environment or terrain. Geopolitics refers to the study of power over space and territory relationships in the past, present, and future. Besides, it studies the relationship among politics, geography, demography, and economics. A realist and mainstream understanding of geopolitics reflects a different perspective study of geopolitics that is concerned with how geographical factors, such as territory, population, strategic location, and natural resource endowments, as modified by economics and technology, affect state relations and the struggle for global dominance. As a result, geopolitics as a profession only demonstrates the state’s ability to control space and territory, as well as the importance of individual states’ foreign policies and international political ties.

However, contemporary power analysis can no longer be limited to inter-state relations. A conceptual analysis casts doubt on the one-dimensional approach of geopolitics, which offers only a narrow articulation of power analysis solely at the international level.[xiii] An interdisciplinary framework that focuses on IR, geography, and history that represents a comprehensive and rather inclusive interpretation of geopolitics, seems to be an alternative to the above-mentioned classical vision of geopolitics focused on realist/neorealist accounts of IR.[xiv] If geography seems to be out there, it is also within us, as an imagined spatial relationship for critical geographers such as Yves Lacoste gathered in the French Institute of Geopolitics (Paris VIII University) and Hérodote Review founded in 1976. This intellectual stance on geopolitics was mainly developed in France where geopolitical reasoning was considered something equal to Nazi expansionism, totalitarianism, and political extremism after the Second World War.[xv] If geopolitics was perceived by many as a Hitlerian concept[xvi], its successful re-apparition seems to be parallel with the development of democratic regimes, the idea of self-determination for peoples, and the influence of modern media.[xvii]

The idea of the French school of geopolitics emerges from the necessity to defend a new conception of geopolitics and distinguish it from geography.[xviii] While geopolitics consists of all aspects of political life, both internal and external, it also deals with all of the power rivalries in the territories.[xix] And, geography represents a unique and major tool to analyze these rivalries. So, everything is geopolitical in the sense that the term “geopolitics” gains a quite different and even radical meaning for Lacoste.[xx] As political analysis should be found on geographical reasoning, geopolitics represents the “spatial analysis of political phenomena”.[xxi] And, there are rivalries not only between states but also between political movements or secret armed groups.[xxii] Regarding the control and domination of large or small areas, Lacoste and his colleagues were among the first to realize that geopolitics is above all a political and strategic kind of knowledge.[xxiii]

Accordingly, one can especially highlight the complexity of geopolitical cases. This represents a situation depending on the diversity of our complex representation of a geopolitical phenomenon.[xxiv] It would be crucial to analyze multiple spatial linguistic, political, religious, and demographic ensembles together with their subjective characteristics. Hence, to better understand geopolitical complexity, one must accept that we live in a subjective environment and that the majority of the geopolitical conflicts are internal; that is, within states, rather than out there in interstate relations.[xxv] The contemporary idea of “Internal Geopolitics” formulated by Béatrice Giblin is closely linked to the methodology of “geopolitical representations” and it can be perceived as a tool to understand interactions and perceptions between social actors at both internal and external levels of analysis.[xxvi]

The concept of “Internal Geopolitics” developed in this respect has redefined the boundaries of geopolitical conflicts and power rivalries in the context of subnational and local perspectives.[xxvii] Here, one may investigate multiple links between geopolitics and democracy.[xxviii] It was at the end of the USSR (1991) that the use of the word “geopolitics” began to spread. Where there is a decline in authoritarianism, multiple situations can be more and more subject to geopolitical analysis. Democracy is a term that covers contradictory representations based on a given territory.[xxix] For this, democracy reflects an ideal and it is, therefore, a geopolitical representation and an idea. It would be crucial to understand why some people, groups, and parties, impose their ideas in some places and times while others are discarded.[xxx]

In addition, the term “geopolitics” has resurfaced to designate “antagonisms less ideological than territorial” over time.[xxxi] At this point, Lacoste points out: “The term geopolitics came out of the shadows at the time of the Vietnam-Cambodia war in 1979. This conflict stunned public opinion which does not understand how two ‘communist brothers’, united against American imperialism, could go to war only for one territory”.[xxxii] Therefore, the war started between these two communist neighbors of the desire of each of the two countries to control part of the Mekong Delta. In other words, the scope of geopolitical issues, shadowed by the ideological conflicts between the two blocs during the Cold War, expanded in terms of both the subject and the actors with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain and the disintegration of the Soviet Union.[xxxiii]

Lacoste began to emphasize that politics and geography affect each other mutually.[xxxiv] From this, we can think about the relationship between geopolitics and geostrategy, which seem to be used interchangeably. The strategy uses battles by determining the location and the most appropriate time to affect the result. Put in a mainstream fashion, geostrategy is to create a strategy based on geographical data.[xxxv] Both physical and human geography have an impact on the political realm; so, we may conceive political geography as the combination of these two “primary geographies”. At the same time, one should be aware of geographical determinism: The geographical environment has an impact on geopolitics and cartography because geography presents threats together with opportunities to countries. To be clear, when making foreign policy and security decisions, geographical criteria should not be the only consideration.

Before we go on to analyze geopolitics as a “method” in the following section, it will be necessary here to briefly focus on the distinctions between political geography, geopolitics, and geostrategy. These concepts are often defined in contradictory ways. We can think about how we consider “space” to establish an operational distinction between these concepts. Space can be successively considered as a framework, issue, or theater. Space nevertheless seems to be a good avenue for reflection to determine the specificity and the links existing between these disciplines.[xxxvi] Here, one can identify the contours existing between geopolitics (1), political geography (2), and strategy (3) both depending on physical factors.

For Lacoste, political geography is only a simple step in the formulation of geopolitics.[xxxvii] While the former focuses on geographical events and provides political explanations for them, the latter focuses on political events, provides them with a geographical explanation, and examines the geographical aspects of these events.[xxxviii] Political geography considers space as a framework; geopolitics considers space as an issue; and geostrategy considers space as a theater.[xxxix] First, space as a frame designates that political geography is based on the description of the global political framework. This framework or setting has been formed of territories, lines, and poles. The most classic political territories are the states. The other political territories are of three types: sub-state territories, formed by regions or other types of administrative entities; supra-state territories, made up of meetings of states in international governmental organizations (IGOs) with a global or regional vocation; and finally, transnational territories. This final category can include linguistic and religious territories, and homogeneous territories in terms of the level of development.[xl] The political poles par excellence are the capitals (state or regional), the decision-making centers such as permanent headquarters of IGOs, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), or companies, that organize and manage space. However, the study of territories, lines, and political poles is not an end in itself. Rather, we can say that it constitutes a first step in bringing together the geographical elements necessary for geopolitical analysis.

Secondly, considering space as an issue, the dynamic approach to political territories is the primary element of any geopolitical investigation. However, it must also include, as implied by the notion of stake, the existence of identifiable actors, each developing territorial representations and strategies. If political geography describes the political framework at a given point in time, geopolitics is first concerned with describing the spatial evolution of this framework. Indeed, geopolitics is a part of political geography. It represents an eminently psychological part in its broader sense, especially about the particular question of the reciprocal images that political units maintain with each other.[xli] The main reason why the actors must be put in the center is to think of power not only as an instrument of domination but as a complex phenomenon, made of rivalries and supervision of the population.[xlii] Hence, actors who fight and clash for domination or control of the territory, play key geopolitical roles.[xliii] Among these actors, the most classical one is undoubtedly the state (which can therefore be considered both as an object of political geography and a subject of geopolitics) but also, but we should also consider not only the “peoples” (a general concept bringing together all forms of organized and differentiated human groups, from the tribe to the nation) but also the “political, economic and military structures”.

On this basis, each actor develops its territorial representations. This is a conception of space and its political framework. Territorial representation can be akin to land claims. Each actor in a hierarchy of territories can distinguish a central, fundamental space and less important peripheries. To achieve its objectives, an actor deploys a strategy. The notion of strategy is understood here as the means to achieve its ends and not as a specific military development. The notion of strategy has long been developed almost exclusively in the military sphere.[xliv] Any actor in a geopolitical situation develops a strategy; this can be not only a civil or political strategy but also an economic and/or military one.[xlv] Besides, not all the issues are territorial: Geopolitics is mainly interested in territorial ones; so, it is clearly distinguished from IR or Political Science. Therefore, we will consider geopolitics here as the description of the power rivalries in which the territory is at stake.

Finally comes the idea of space as a theater, which is the place of confrontation between the armed forces.[xlvi] Strategists use the term “theater of operations” to signify more precisely the space where military confrontation takes place; the place where a tactic is implemented. The military distinguishes between strategy which considers military problems on a local, regional, or global scale and tactics which envisage them on a large scale (tactics being the local application of a strategy). Thus, as Rosière states, space considered as a theater should therefore be the object of “Geotactics”.[xlvii] Geostrategy could also be defined as the study of the geographical parameters of the strategy, emphasizing the spatial dimension. Furthermore, geostrategy is, like geopolitics, a dynamic description in which one can highlight territories, lines, and strategic poles, or of higher strategic value. Strategy cannot be limited to the military domain, but it also integrates economics or politics into the analysis.[xlviii]

While geopolitics seems to be a concept that naturally intertwines with IR, it also appears as a broad method based on a historical and geographical approach. In this respect, geopolitics aims to examine contemporary power conflicts and rivalries over regions.[xlix] Specifically, it can be conceived as a method that contributes to the discipline of IR within the scope of foreign policy studies and regional studies. Most importantly, it refers to geographical knowledge which itself is a method indeed. This method is a geographical know-how that aims to know how to think and represent spatial configurations. Hence, geopolitics reflects a test method of reality, based on a geographical and historical approach to understanding how power, peace, prosperity, and freedom, are exerted in concrete territories in precise temporal conjunctures.[l] If geopolitics is knowledge derived from geography, this reasoning is based first on a spatialized approach to phenomena.[li]

Geopolitics remains a method of analysis capable of considering the complexity based on multidisciplinary analyses in several scales, spaces, and time.[lii] The geopolitical method depends on the combination of an ensemble of political, economic, geographical, demographic, ethnological, or sociological factors. Accordingly, geopolitical situations are different from one issue to another, from one case study to another. Elsewhere, geopolitics presents a broad field of study ranging from local and national to regional and international scales.[liii] In addition to the interstate rivalries, geopolitics also indicates some issues that take place within an infra-state framework. Thus, the aim of geopolitics is the conflicts and rivalries of contemporary power enrolled in territories.

Representation as the primary conceptual and methodological tool in geopolitical thinking stands at the center of any geopolitical analysis trying to answer the following question: who speaks? According to Lacoste, geographical representations have a huge impact on the analysis of rivalries for territory.[liv] As each player in the territory has a more or less subjective meaning of the territory for itself, any geopolitical analysis should decrypt both geographical and historical reasoning. Therefore, as stated by Giblin, there is no geopolitics without geography, which is a motto for Lacostian geopolitics.[lv] In this sense, the geopolitical is grounded in the geographical.[lvi] At this point, Lacoste defines representation as “the set of ideas and collective perceptions of a political, religious or other nature which animate social groups, and which structure their vision of the World”.[lvii] The geopolitical method is based on the idea that the contradictory representations are systematically described and that the rationality and logic of the different actors are explained. On this ground, geopolitics is interested in the causes of conflict and power rivalries based on the territories.[lviii]

Moreover, the representational perspective of geopolitics aims to understand spatial ensembles formed by diverse social and historical categories, from which symbols and slogans of a given political project follow such as icons, maps, and “major goals”.[lix] From this perspective, geopolitics indicates a global method of analysis for concrete social and political situations covering both local, national, and international levels, along with political discourses and their cartographical representations. Additionally, Michel Foucher states that geopolitics is “a comprehensive method of analyzing geographically concrete socio-political situations viewed in terms of their location and the usual representations which describe them”.[lx] According to Lacoste who comprehends geopolitics as a method above all in the context of different levels of geographical analysis (cities, regions, or nations), it is a concept that examines the competition for power and influences both at the regional and social level within the framework of the control of large or small territories.[lxi]

In this direction, geopolitics, which can be conceived as a kind of methodology that studies power rivalries in different parts of the world, also represents an approach that goes beyond the states.[lxii] Contrary to the widely conceived one-dimensional and deductive version of geopolitics (especially related to realist/neorealist accounts of IR), representational geopolitics involves rather a broad study of power rivalries on territories that may contain an interstate conflict for sovereignty by diverse actors or a geographical influence in a given zone, or even internal and regional situations within a state.[lxiii] The concept of representation is a collective perception based on a geographical-historical identity that occurs as a result of long periods (usually centuries) and in a specific region, and it is all about the ideas that shape different social groups and their visions of the world.[lxiv] Besides, this representational approach is not only a reference for social construction over a diversity of identities in a given geography (i.e., a city, a province, a state or a region or union) but also an analytical tool to understand interactions and perceptions between social actors composed of states, political parties, armies or rebel armed forces, diverse social groups, individuals, researchers and so on. Similarly, the French school of geopolitics differentiates itself from post-structuralist and critical geopolitics mainly based on discourse analysis, deconstruction of discourses, and critical investigation of the meaning of space and politics influenced by French philosophers Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault.[lxv]

Representational geopolitics designates a way of seeing, conceiving, and judging events as a whole, positioning oneself in terms of geopolitical postures, and helping make decisions. All these actions have, therefore, a foundation that interests ideological and religious expressions while going beyond them to be inspired by the collective imaginaries that are the essence of the notion of representation in this geopolitical setting. Hence, the representational approach is “a selective combination of images used in diverse categories of social and historical area” as asserted by Foucher.[lxvi] Therefore, geopolitical actors and social imaginaries are inseparable; a geopolitical representation does not only mean territorial issues, and objects of rivalry but also collective cognitive perceptions and imaginaries over territories.[lxvii] Representations emerge over time and may encompass cultural, historical, ethnic, and geographical attributes; among the actors concerning these territorial issues. The study of the actors, the understanding of power relations in societies or institutions, is at the heart of geopolitical reasoning. The description of the actors’ strategies, which are developed over long or short times, is to be placed in their geopolitical context.[lxviii]

From this point of view, one may also ask the following questions: Are borders important in the context of globalization? Is there a world beyond borders? Or can there be a sort of “return of borders[lxix]”? It would be crucial to be aware of a world without borders developed by the discourse on globalization… The “obsession with borders” becomes even more evident and important.[lxx] For French geopoliticians such as Pascal Boniface and Yves Lacoste, borders never actually disappeared.[lxxi] At this point, Alexandre Defay asks whether borders necessarily have to be material.[lxxii] Boundaries can also be intellectual. Or do they not matter in geopolitics? Therefore, there is room for the analysis of intangible borders. As Foucher outlines, borders form the front’s most extreme and thinnest line.

A map is a means and an area. The idea of the map is also based on a representation. It is also an idea and there is a ruling thought behind it.[lxxiii] Mapping, or cartography put in another way, remains a tool for marking a territory or all the representations of this territory. Essentially, mapping remains very subjective.[lxxiv] On the other hand, each country has its map: it shows an “objective truth”. The map of France or Germany seems to have existed for “centuries” and looks like the truth. At this level, one can note a certain fluctuation between objectivity and subjectivity. For this reason, maps are not at all neutral.[lxxv] They are only a picture of reality and not an objective truth, so they are largely subjective. Maps are not frozen things instead they are dynamic. Therefore, they impact political decisions and leaders’ choices.[lxxvi] In this context, maps are rich and valuable elements in the geopolitical imagination. In a map, it is possible to guess and understand the choices of the author of the map: What is he/she talking about? What is at stake with this map? Lacoste explains that these rivalries cannot be explained only by the stake represented by this territory but also by the representations of the protagonists.[lxxvii]

Power rivalries in territories affect not only the territory itself but also the populations living there. Therefore, territories do have a double meaning. First, this is physical space with relief, climate, cities, and countries; on the other hand, territories represent mentally constructed spaces.[lxxviii] In this sense, there is neither a geopolitical law nor geopolitical theorization. Instead, geopolitical case studies or monographs are much more valuable to grasp a specific geopolitical situation. In short, geopolitics, whatever the pretexts, is not a tool in the service of colonialism, imperialism, or expansionism. On the contrary, it is a knowledge and especially a method. A geopolitical study seeks to establish how many distinct perspectives exist rather than what the true position is. Therefore, a representation is not only a reflection on a territory or a phenomenon that takes place there but also the result of a certain reasoning that associates the elements of the real to build what appears as a truth to defend. This is how Lacoste apprehends geopolitics as “a way of thinking about terrestrial space and the struggles that take place there”.[lxxix] In other words, geopolitics is not a scientific theory nor a theoretical approach, but it denotes, above all, a set of concepts related to methodology.[lxxx]

As geographical reasoning with different spatial levels of analysis (intersection of multiple ensembles of space) is needed for a comprehensive geopolitical framework, historical reasoning is also crucial in that analysts should integrate different periods (both past and present) affecting geopolitical representations of different protagonists in a given territory.[lxxxi] In addition, Foucher indicates that geopolitics refers to schools of thought, discourses, and constructions generally accompanied by cartographical images.[lxxxii] Time and space association will then be fundamental because as Giblin suggests, historical reasoning is central to the geopolitical research agenda.[lxxxiii] Besides, geopolitical reasoning has several spatial levels of analysis depending on the geographical framework. Much attention is paid to the precise intersections of spatial sets, whether physical or human, as well as changes in levels of analysis, to understand how a local situation is also influenced by phenomena perceptible at broader levels of analysis: regional, national, international, and, in some cases, global.

In this final section, I present a comprehensive portrayal of teaching geopolitics in Turkish universities by assessing Political Science and IR curricula for both undergraduate and graduate levels. For this, I analyzed the available qualitative ECTS data (course name, objective and content, sources, and if any, 14-week detailed program information in the Bologna Information Systems) including the courses related to geopolitics in the “Political Science and IR/IR” departments in Turkey. Regarding the teaching of geopolitics in Turkey, ECTS contents were analyzed qualitatively as a practical tool in this study as part of the classification and processing of data.[lxxxiv] From this point, the qualitative analysis represented a structured exercise in logically relating categories of data. ECTS stands as the only relevant source to study that issue. For all these reasons, the course names related to geopolitics represent a clue to the approach taken in the courses. However, it should also be noted here that the ECTS information packages of many universities are still not up-to-date and there are recurrent problems with accessing updated course catalogs, which constitutes the main limitation of this research at this level.

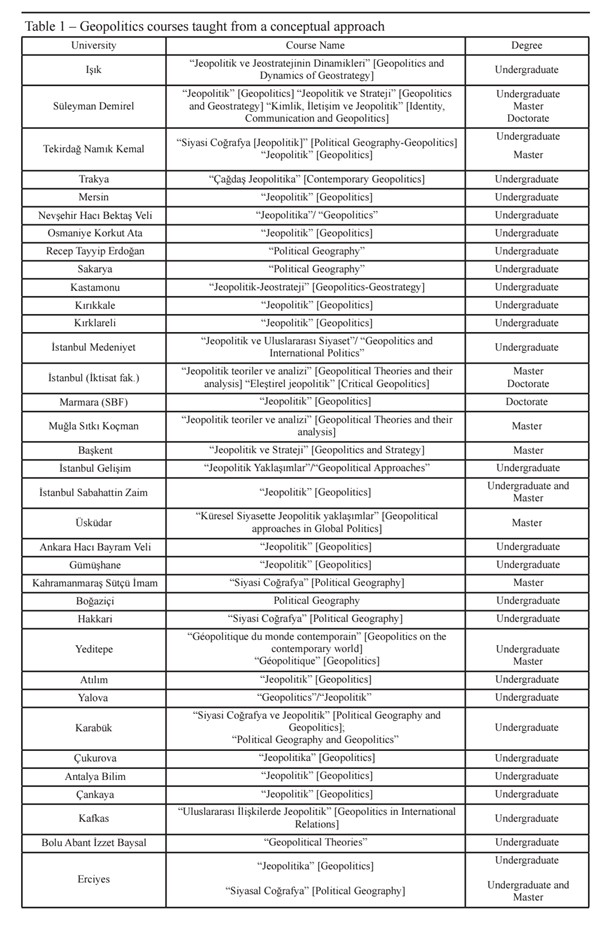

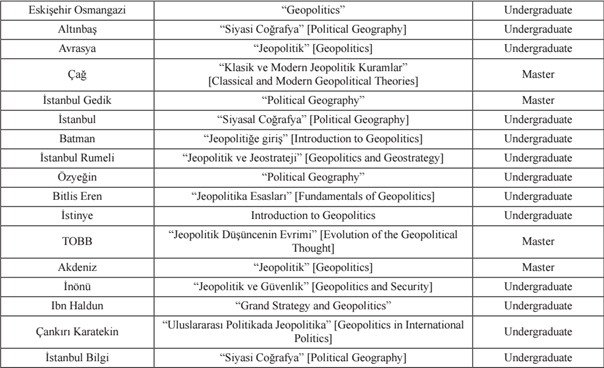

First of all, if more than 120 undergraduate and graduate programs entitled “Political Science and IR” and/or “IR” at universities in Turkey are examined in the context of “Geopolitics”/“Political Geography” courses, it can be seen that these courses are offered at very different levels in the relevant programs of 80 universities at total. Overall, “Political Science IR” and IR departments in 52 universities mostly deal with conceptual and theoretical aspects of geopolitics. Table 1 below shows the courses that can be grouped into this first type. Courses given in Turkish are presented with their English equivalents in parentheses and also with “/” for some courses taught both in Turkish and English. Here, it should be underlined that the concept of geopolitics has many meanings in Turkish, as can be noticed from the variety of course names such as “Jeopolitike giriş/Jeopolitiğe giriş” (“Introduction to Geopolitics”), “Jeopolitik” or “Jeopolitika” in Turkish. This shows that this concept still does not have a consistent usage in Turkish regarding this linguistic cacophony faced by the concept of geopolitics in Turkish terminology.

Table 1 – Geopolitics courses taught from a conceptual approach

Considering the ECTS contents of the vast majority of these conceptual courses, it can be said that they do not reflect a contemporary and pluralistic understanding of geopolitics based on the analysis of representations in the previous section. Precisely, most of the above-mentioned courses lack a broad multi-level analysis consisting of geographical and historical reasoning. First of all, what geopolitics means methodologically in these conceptual courses is a matter that is completely denied. For this reason, the lack of methodological background for the majority of the courses causes conceptual confusion. In this framework, the content of a given geopolitics course based on a geographical and historical method, is often replaced by a course content shaped by “geopolitical theories”. At this point, the title of “theory” in some geopolitics courses can be noticed. Although not in the title, most of the conceptual courses on geopolitics in Turkey have a large share of “geopolitical theories” in the 14-week course plan. The main reason for this can be expressed as the confusion between method and theory in IR education in Turkey.

Another key reason why the teaching of geopolitics does not include generally a methodological perspective is that the courses cannot go beyond the state-centered dimension mainly characterized by national/international power analysis or foreign policy issues. For instance, geopolitics as a concept, descriptively points to many perceptions in the context of sovereignty, border, homeland, security, and national/international strategy. In these geopolitics courses taught from a conceptual approach, geopolitics is rather represented as a “sub-branch of international politics” and is especially widely discussed in this respect. In this framework, some of the courses resemble more “diplomatic history” or “history of IR” courses in terms of content. The main reason for this is that the state-centered perspective dominates the teaching process and does not enable a methodological examination of geopolitics based on various levels of analysis

Besides, from a conceptual point of view, when the syllabi of these 63 courses are classified, it can be stated that there is conceptual confusion in the field of IR, where the fields of geopolitics and political geography are interchangeable and therefore settled in Turkey. There are such amalgamated relations between security and strategy studies, foreign policy, and geopolitical approaches in the Turkish IR domain. Furthermore, the main disciplinary boundaries between geopolitics, political geography, and security studies seem to be largely blurred in the context of geopolitics teaching in Turkey as the majority of these “conceptual” courses mostly reflect the one-dimensional and deductive version of geopolitics based on international power analysis neglecting the other spatial levels of analysis in geopolitics.

Accordingly, while regional/international security themes may be dominant in some of these conceptual courses, geopolitics is treated as an equivalent field to security, foreign policy, and strategy. The reason for this is that, with the effect of the realist/neorealist perspective that dominates the IR field, Turkey’s geopolitical situation and geographical location affect the courses and almost narrow the field of study of geopolitics. Contrary to these problematic tendencies in conceptual courses dominated by “geopolitical theories” and/or security and foreign policy-based understandings, geopolitics is handled only in 6 universities as a method including mostly methodological elements. These courses are offered at Özyeğin, Çukurova, Yeditepe, İstanbul Gelişim, Başkent and Sakarya universities.

Another important point that should be emphasized here is that the map and cartography methods, which are important in geopolitical studies, are explained to the students in very few of the courses listed above. The concepts such as “representation”, “methodology”, “map/mapping” or “cartography” do not generally appear throughout the long list of geopolitics courses offered in Turkey. Representations, maps, and spatial levels of analysis do not generally constitute relevant methodological references in the teaching of geopolitics in Turkey. In that, even though so many courses appear to be conceptual or even theoretical courses, they seem to lack a broad methodologic background. This explains the growing importance of the representational perspective of geopolitics for Turkish IR. For instance, it should be noted that except for a few examples such as Yeditepe University (“Cartography for Social Sciences I-II”), cartography methods in the discipline of social sciences and therefore Political Science and IR are not covered in geopolitics teaching on both undergraduate and graduate levels.

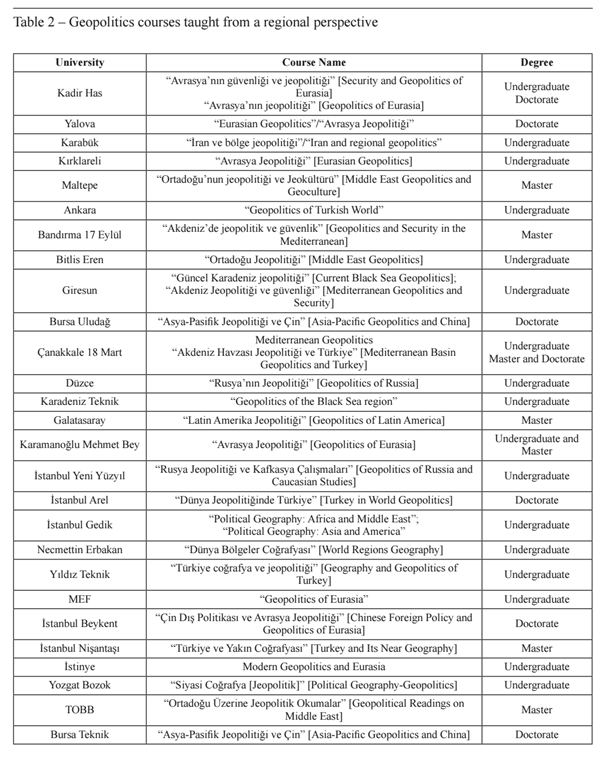

On the other hand, it can be seen that some of the courses related to geopolitics focus on various regions (Eurasia, the Mediterranean, Black Sea, Latin America, the Middle East, Caucasia, Africa, or Asia-Pacific) and some specific countries or demographic areas (Russia, China, Turkey/Turkish world, or Iran) on the axis of regional studies and foreign policy. In Turkey, 27 universities offer courses on geopolitics that will fall into this category (See Table 2). In parallel with the main issues in the conceptual courses, one can note that an approach in the context of regional/international politics and great powers is emphasized instead of the methodological dimension of geopolitics. Nevertheless, the existence of special geopolitics courses on Russia, Iran, and China is noteworthy. At this point, the lack of courses such as European or North American geopolitics or more specifically “US Geopolitics”, “The Geopolitics of Germany”, “The Geopolitics of UK” or “The Geopolitics of France” within the framework of Western and Transatlantic relations is a point to be considered. Within the scope of the courses in this second category, Eurasian region and Eurasianism come to the forefront rather than Europe and America, with a Turkey-centered and Turkey’s neighbors’ perspective. Eight of the 33 courses in this category are related to Eurasia.

Table 2 – Geopolitics courses taught from a regional perspective

While mapping as a key geographical method is not encountered in these courses, an analysis based on geopolitical representations is not even used. From a general point of view, it is very difficult to establish a link between the content of the course and the name given to the course, since a course that can be described as a “regional study” or a “foreign policy of a country” is called “geopolitics”. The most important reason for this can be seen as the denial of the geographical and methodological features of geopolitics, which are seen as the “equivalent” of security, foreign policy, or strategy, in parallel with the conceptual courses. In this framework, the conceptual blurring of geopolitics continues in regional courses as well.

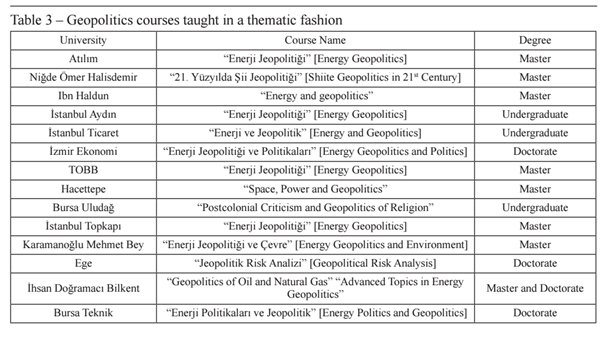

Furthermore, one can state that another part of the geopolitics courses given is handled on a thematic level. In this context, geopolitics emerges within a different spectrum such as “space and power analysis”, “energy security” (mainly centered on oil and gas), “postcolonial geopolitics”, “geopolitics and religion” or even “Shiite geopolitics”. Although different thematical subjects affect geopolitics courses, it would not be wrong to say that especially energy-related issues have a serious impact here. Table 3 shown below lists the courses that may fall into this category bringing together 14 universities.

Table 3 – Geopolitics courses taught in a thematic fashion

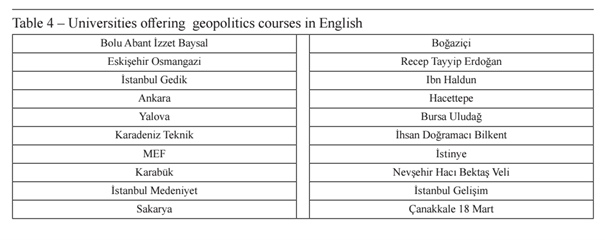

While the geopolitical method is included in the sources of some courses such as “Shiite Geopolitics in 21st Century” in this category, the methodological dimension generally lacks in the course contents, objectives, and 14-week course plans, as seen in the conceptual and regional courses. On the other hand, the addressing of geoeconomics in courses such as “Geopolitical risk analysis”, which deals with risk analysis and geopolitics together, remains important in terms of diversifying geopolitical education in Turkish universities, although it does not contribute directly to the scope of the geopolitical method. Furthermore, it would be appropriate to briefly mention the language in which these courses are offered. While most of the geopolitics courses given in conceptual, regional, and thematic contexts in Turkey are in Turkish, 20 departments stand out where English as a medium of instruction is used (See Table 4).

Overall, while 81 of all the geopolitics courses given in Turkey are taught in Turkish, 32 of them are taught in a foreign language. In 20 departments, geopolitics courses are taught in English, as can be seen in the table above, while French is the language of instruction in geopolitics in only one francophone department (Political Science and IR, Yeditepe University) offering French as the foreign language of instruction for geopolitics and related courses such as Cartography in Social Sciences 1-2. If we analyze the geopolitics courses given in Turkey in the context of conceptual, regional and thematic elements, we find that at Özyeğin (English instructed), Yeditepe (French instructed), Istanbul Gelişim (Turkish/English instructed), Çukurova (Turkish instructed), Başkent (Turkish instructed) and Sakarya (Turkish instructed) there are more or less consistent and comprehensive courses on geopolitics in terms of geopolitical method.

Table 4 – Universities offering geopolitics courses in English

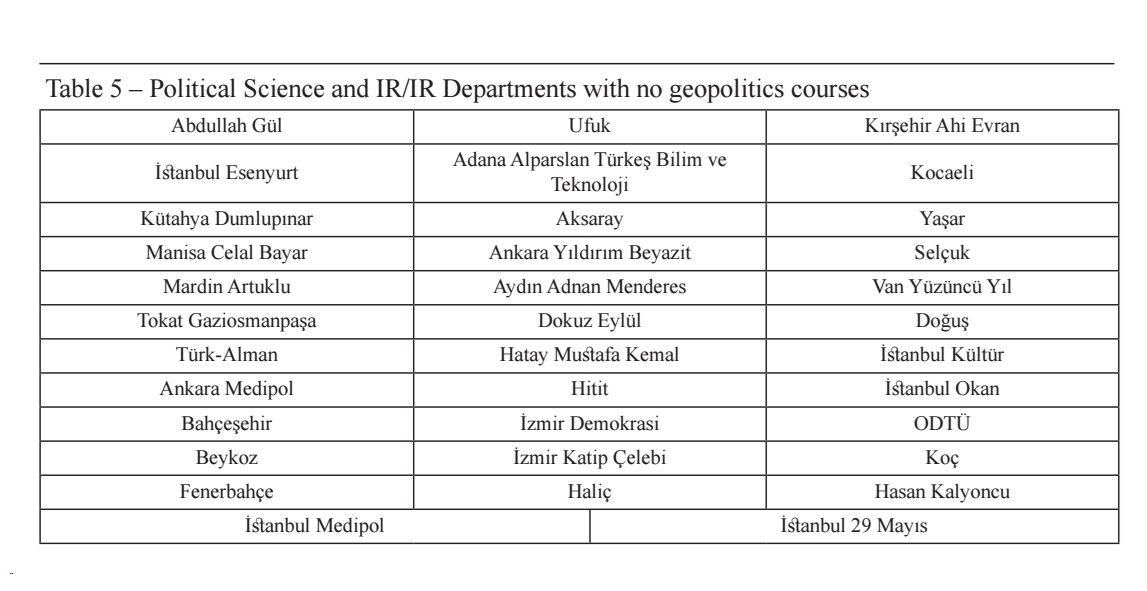

The fact that almost half of the geopolitics courses in these six universities/departments are taught in a foreign language emphasizes the importance of foreign languages such as English and French and sources (books, articles, etc.) written in these languages. On the other hand, besides English and French, the role of Turkish as the language of instruction in geopolitics courses is undeniable even if methodological issues are not usually covered in these courses and the Turkish is not used on this ground. On the other hand, 35 Political Science and IR/IR departments in Turkey do not offer any geopolitics courses (see Table 5).

Table 5 – Political Science and IR/IR Departments with no geopolitics courses

In this study, I analyzed the conceptual framework of geopolitics as a distinct field of study as well as its methodology from a critical perspective and elucidated the current situation of geopolitics teaching in Turkey by evaluating the courses available on the ECTS information packages on university websites. I considered geopolitics as a critical method based on cartography, territoriality, and geopolitical representations. Together with interstate rivalries, it refers to diverse conflicts and rivalries taking place within an infra-state framework in the context of multiple territorial scales. The significance of geopolitics as a complex method of analysis has been reflected in this critical background developed especially by Yves Lacoste and his colleagues, in the context of geopolitical representations, which refer to a collective perception based on a geographical-historical context

Focusing on our findings, I consider that the methodological aspects we examined in the previous parts were either completely ignored or kept in the background, in light of the ECTS information on the university websites. Most importantly, geopolitics teaching in Turkey does not prioritize the level of methodological inquiry. Similarly, on theoretical ground, while geopolitics in Turkey seems to be falsely perceived as something equal to a hard realist and state-centric academic subfield representing even a strong military tutelage, it lacks substantially a broad multi-level analysis and geographical and historical reasoning which constitute two crucial sources of contemporary geopolitical thinking.

Considering the lack of representation as an analytical tool in the overall teaching of geopolitics in Turkey, understanding geopolitics as a representational method is a marginal tendency today. Accordingly, the evocation of new actors as sources of “collective representation” other than the state, lacks as well in the teaching of geopolitics. The teaching of geopolitics reflects rather a state-centric approach that still dominates the discipline and it can be seen in diverse geopolitics courses taught in many universities. From another point of view, when the courses are examined in general, it should be emphasized that unlike “geopolitical methods”, the understanding of “geopolitical theories” is heavily entrenched in Turkey. In this sense, the historical and geographical reasoning should be added in the Political Science and IR Curricula on geopolitics in Turkey.

Finally, while the use of maps remains crucial in geopolitical practice and thinking, I argue that the cartographical deficiency of geopolitics teaching in Turkey indicates a relatively underdeveloped level of conception of the field. Eventually, courses on cartography could not be generalized in Political Science and IR teaching in Turkey in terms of academic linkages between IR, geopolitics, and geography. Only in a few universities, is it possible to find courses based on cartography, spatiality, and geographical background of geopolitics... Establishing a method based on notions such as geographical and historical representation remains one of the main challenges for the geopolitics teaching in Turkey. If there will be a room for methodology at this point, one could only consider to what extent a specialization called geopolitics can be developed in Political Science and IR departments, or how creating a master’s program in geopolitics can be thought...

Notes

[i] Yves Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Larousse, 2009), 9.

[ii] Klaus Dodds, Geopolitics. A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 1.

[iii] Barbara Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes et Concepts (Paris: Armand Colin, 2019), 19.

[iv] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire, 9.

[v] Jarol B. Manheim and Richard C. Rich, Empirical Political Analysis, Research Methods in Political Science, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981).

[vi] Gordon Mace and François Petry, Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche, (Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2000), 80.

[vii] Robert K. Yin, Case Study Research: Design and Methods, (Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989).

[viii] Jean-Pierre Deslauriers, Recherche qualitative. Guide pratique, (Montréal: McGraw-Hill, 1991), 59-78.

[ix] Mace and Petry, Guide d’élaboration, 90.

[x] Ibid., 94.

[xi] Ibid., 90-91.

[xii] See Colin S. Gray, “Inescapable geography.” The Journal of Strategic Studies 22: 2-3 (1999): 161-177.

[xiii] See further information: Saul B. Cohen, Geopolitics, The Geography of International Relations (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003); Colin Flint, Introduction to Geopolitics (London: Routledge, 2006).

[xiv] Øyvind Østerud, “The Uses and Abuses of Geopolitics.” Journal of Peace Research 25 2 (1988): 191-199.

[xv] See further information: Paul Claval, “Hérodote and the French Left,” in Geopolitical Traditions. A century of geopolitical thought, ed. Klaus Dodds and David Atkinson (New York: Routledge, 2000), 239; Klaus Dodds and David Atkinson, preface to Geopolitical Traditions. A century of geopolitical thought, ed. Klaus Dodds and David Atkinson (New York: Routledge, 2000), xiv.

[xvi] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 7.

[xvii] Claval, “Hérodote and,”, 242.

[xviii] Yves Lacoste, La géographie, ça sert, d’abord, à faire la guerre (Paris: La Découverte, 2012 [1976]), 46.

[xix] See Béatrice Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement géographique d’avant-garde,” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 3-13.

[xx] V. D. Mamadouh, “Geopolitics in the nineties: one flag, many meanings,” GeoJournal 46 4 (1998): 239.

[xxi] Østerud, “The Uses and,” 197.

[xxii] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire, 8.

[xxiii] Dodds, Geopolitics. A Very, 48.

[xxiv] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 3.

[xxv] Béatrice Giblin, “Géopolitique interne et analyse électorale,” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 71-89.

[xxvi] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 3.

[xxvii] See Philippe Subra, “La géopolitique, une ou plurielle? Place, enjeux et outils d'une géopolitique locale,” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 45-70.

[xxviii] Béatrice Giblin, “Éditorial,” Hérodote 3 130 (2008): 13.

[xxix] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 23.

[xxx] Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes.

[xxxi] Lacoste, La géographie, ça sert.

[xxxii] Ibid., 43-44.

[xxxiii] Pascal Boniface, La Géopolitique (Paris: Eyrolles, 2017), 31.

[xxxiv] Frédéric Encel, Comprendre la géopolitique (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2011), 62-63.

[xxxv] Gray, “Inescapable geography”.

[xxxvi] Stéphane Rosière, “Géographie politique, géopolitique et géostratégie: distinctions opératoires,” L'information géographique 65 1 (2001): 35.

[xxxvii] Lacoste, La géographie, ça sert.

[xxxviii] Ladis K. D. Kristof, “The Nature of Frontiers and Boundaries,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 49 3 (1959): 269-282.

[xxxix] Rosière, “Géographie politique,” 36.

[xl] Ibid., 37.

[xli] Thierry de Montbrial, Géographie politique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2006), 20.

[xlii] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 2.

[xliii] Rosière, “Géographie politique,” 37-38.

[xliv] Montbrial de, Géographie politique, 21.

[xlv] Rosière, “Géographie politique,” 39-40.

[xlvi] Ibid., 40.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Ibid.

[xlix] Alix Desforges, Barbara Loyer, Jérémie Rocques, Joséphine Boucher, Julie Mathelin and Pierre Verluise. “Existe-t-il une méthode géopolitique?” Diploweb.com: la revue géopolitique (2019, 19 October), accessed March 30, 2022.

[l] Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes.

[li] Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement,”

[lii] Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes, 29.

[liii] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire, 26.

[liv] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire.

[lv] Giblin, “Éditorial,” 4.

[lvi] Claval, “Hérodote and,” 249.

[lvii] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 3.

[lviii] Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes.

[lix] Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement,”.

[lx] Michel Foucher, Fronts et frontières. Un tour du monde géopolitique (Paris: Fayard, 1991).

[lxi] Yves Lacoste, Géopolitique de la Méditerranée (Paris: Armand Colin, 2009), 5.

[lxii] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire, 25.

[lxiii] Barbara Loyer, “Retour sur les publications de l'équipe d'Hérodote et l'analyse des problèmes géopolitiques en France, une ambition citoyenne,” Hérodote 4 135 (2009): 198-204.

[lxiv] Encel, Comprendre la géopolitique, 65-66.

[lxv] See further information: Mamadouh, “Geopolitics in the nineties”; Alexander B. Murphy et al, “Is there a politics to geopolitics?” Progress in Human Geography 28 5 (2004): 619-640.

[lxvi] Foucher, Fronts et frontières, 4.

[lxvii] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 4.

[lxviii] Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement”.

[lxix] Michel Foucher, Le Retour des Frontières (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2020).

[lxx] Michel Foucher, L’Obsession des frontières (Paris: Perrin, 2012).

[lxxi] Boniface, La Géopolitique; Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire.

[lxxii] Alexandre Defay, Jeopolitik (Ankara: Dost Yayınevi, 2005), 50.

[lxxiii] Foucher, Fronts et frontières.

[lxxiv] Defay, Jeopolitik.

[lxxv] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire.

[lxxvi] Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement”.

[lxxvii] Lacoste, Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, 25-26.

[lxxviii] Loyer, Géopolitique. Méthodes, 45.

[lxxix] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire, 8.

[lxxx] Estelle Menard, Léa Gobin and Selma Mihoubi, “Entretien avec Yves Lacoste: Qu’est-ce que la géopolitique?” Diploweb.com: la revue géopolitique, (2018, October 4), accessed March 20, 2022.

[lxxxi] Lacoste, Géopolitique. La longue histoire.

[lxxxii] Foucher, Fronts et frontières.

[lxxxiii] Giblin, “La géopolitique: un raisonnement”.

[lxxxiv] Jean-Louis Loubet Del Bayle, Introduction aux méthodes en sciences sociales, (Toulouse: Privat, 1986), 124-157; Manheim and Rich, Empirical Political Analysis, 245-270.

Boniface, Pascal. La Géopolitique. Paris: Eyrolles, 2017.

Claval, Paul. “Hérodote and the French Left.” In Geopolitical Traditions. A century of geopolitical thought, edited by Klaus Dodds and David Atkinson, 239-267. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Cohen, Saul B. Geopolitics, The Geography of International Relations. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

Defay, Alexandre. Jeopolitik, Ankara: Dost Yayınevi, 2005.

Desforges, Alix, Barbara Loyer, Jérémie Rocques, Joséphine Boucher, Julie Mathelin and Pierre Verluise. “Existe-t-il une méthode géopolitique?” Diploweb.com: la revue géopolitique (2019, 19 October). Accessed March 30, 2022, https://www.diploweb.com/Video-B-Loyer-Existe-t-il-une-methode-geopolitique.html

Deslauriers, Jean-Pierre, Recherche qualitative. Guide pratique, Montréal: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

Dodds, Klaus and David Atkinson. Preface to Geopolitical Traditions. A century of geopolitical thought, edited by Klaus Dodds and David Atkinson, xiv-xvi. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Dodds, Klaus. Geopolitics. A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Encel, Frédéric. Comprendre la géopolitique. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2011.

Encel, Frédéric and Yves Lacoste. Géopolitique de la nation France, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2016.

Flint, Colin. Introduction to Geopolitics. London: Routledge, 2006.

Foucher, Michel. Fronts et frontières. Un tour du monde géopolitique. Paris: Fayard, 1991.

Foucher, Michel. L’Obsession des frontières, Paris: Perrin, 2012.

Foucher, Michel. Le Retour des Frontières, Paris: CNRS Editions, 2020.

Giblin, Béatrice. “Éditorial.” Hérodote, 3 130 (2008): 3-16.

Giblin, Béatrice. “La géopolitique: un raisonnement géographique d’avant-garde.” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 3-13.

Giblin, Béatrice. “Géopolitique interne et analyse électorale.” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 71-89.

Gray, Colin S. “Inescapable geography.” The Journal of Strategic Studies 22: 2-3 (1999): 161-177.

Kristof, Ladis K. D. “The Nature of Frontiers and Boundaries.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 49 3 (1959): 269-282.

Lacoste, Yves. La géographie, ça sert, d’abord, à faire la guerre. Paris: La Découverte, (2012) [1976].

Lacoste, Yves. Dictionnaire de Géopolitique, Paris: Flammarion, 1993.

Lacoste, Yves. Vive les nations, Destin d'une idée géopolitique, Paris: Fayard, 1997.

Lacoste, Yves. Géopolitique. La longue histoire d’aujourd’hui. Paris: Larousse, 2009.

Lacoste, Yves. Géopolitique de la Méditerranée. Paris: Armand Colin, 2009.

Lacoste, Yves. La question post-coloniale. Paris: Fayard, 2010.

Loubet Del Bayle, Jean-Louis, Introduction aux méthodes en sciences sociales, Toulouse: Privat, 1986.

Loyer, Barbara. “Retour sur les publications de l'équipe d'Hérodote et l'analyse des problèmes géopolitiques en France, une ambition citoyenne.” Hérodote 4 135 (2009): 198-204.

Loyer, Barbara. Géopolitique. Méthodes et Concepts, Paris: Armand Colin, 2019.

Mace, Gordon and Petry, François, Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche, Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2000.

Mamadouh, V. D. “Geopolitics in the nineties: one flag, many meanings.” GeoJournal 46, 4 (1998): 237-253.

Manheim, Jarol B. and Richard C. Rich, Empirical Political Analysis, Research Methods in Political Science, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981.

Menard, Estelle, Léa Gobin and Selma Mihoubi. “Entretien avec Yves Lacoste: Qu’est-ce que la géopolitique?” Diploweb.com: la revue géopolitique, (2018, October 4). Accessed March 20, 2022, https://www.diploweb.com/Entretien-avec-Yves-Lacoste-Qu-est-ce-que-la-geopolitique.html

Montbrial, Thierry de. Géographie politique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2006.

Murphy, Alexander B., Mark Bassin, David Newman, Paul Reuber and John Agnew. “Is there a politics to geopolitics?” Progress in Human Geography 28 5 (2004): 619-640.

Østerud, Øyvind. “The Uses and Abuses of Geopolitics.” Journal of Peace Research 25 2 (1988): 191-199.

Rosière, Stéphane. “Géographie politique, géopolitique et géostratégie: distinctions opératoires.” L'information géographique 65 1 (2001): 33-42.

Subra, Philippe. “La géopolitique, une ou plurielle? Place, enjeux et outils d'une géopolitique locale.” Hérodote 146-147 (2012): 45-70.

Yin, Robert K., Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989.