Haluk Özdemir, Kırıkkale University

A recent debate has emerged in the literature about a need for more global International Relations (IR), one which is truly international, to be worthy of its name. This paper outlines the multi-dimensional fragmentation in IR, which has prevented the emergence of a genuinely integrated and global discipline, and created a context in which the periphery cannot make original contributions to the core. The main purpose of this paper is to point out the major obstacles for such original contributions that emanate from the periphery itself. Aside from the general core-periphery fragmentation in the discipline, the periphery is collapsing within itself. From that perspective, the core and the periphery look more integrated, while the real division is between the periphery and the outer periphery. The outer periphery, while mostly invisible to the core, has real effects in IR practice, yet its nature and problems are not looked upon or handled by the current literature. Based on this observation, and using the Turkish example, four major problems of the outer periphery that affect the periphery and curtail its potential for original contributions are identified: (1) apathy towards western IR; (2) conspiracy theorizing; (3) chronological historicism; and (4) the outer periphery’s influence on the mainstream periphery. After discussing these problems, it is concluded that the periphery can make contributions to the core only after it has helped the outer periphery solve its problems, and integration within the periphery is achieved. Only then can original contributions of the periphery to a truly international IR be possible.

The International Relations (IR) discipline was born as a liberal project, out of a search for global peace in the years following the First World War. International conflicts and wars are caused by conflicting perceptions of interests and clashing world-views. Therefore, in order to understand international problems, such as wars, and prevent them from recurring, the discipline needs multiple and all-inclusive perspectives. At the outset, however, the discipline was heavily shaped by western perspectives. Right from the start, Edward H. Carr saw the main problem with the discipline by pointing to its British origins and the power-political roots of the paradigmatic differences. The reason for the obsession with liberal perspectives of peace in the earlier years of the discipline was that other “people had … little influence over the formation of current theories of international relations which emanated almost exclusively from the English-speaking countries.”[i] The new discipline was heavily influenced by the dominant powers’ perspectives, and biased towards peace, liberal economy and democratization, ignoring the existence of alternative worlds and their influence over the practice of world politics. On the other side of the coin, since war and authoritarianism still continue to shape the practice, we cannot ignore their existence. However, in the early stages of the discipline, liberal worldviews were presented by idealist thinkers as a matter of global consensus. Again, this superficial and false consensus was, in Carr’s words, a result of “ostentatious readiness of other countries to flatter the Anglo-Saxon world by repeating its slogans.”[ii]

After Carr published his book, realism dominated the intellectual world of IR, as had been the case for liberalism in the inter-war period. Paradigms changed but the nature of the problem remained the same: western originated theories monopolized the whole discipline. This monopoly widened the gap between the constricted theories and wide-ranging political practices. In the following decades, IR remained mainly an Anglo-American discipline, but the practice of international relations continued to be shaped by a variety of world visions. Anglo-American preeminence in the discipline is understandable to a certain extent, and it is possible to identify three main reasons for this: (1) western dominance in world political and economic affairs; (2) the emergence of modern international relations in the European west, based on the principle of sovereignty after the Westphalia treaties of Munster and Osnabruck in 1648, and then, its expansion from there to the rest of the world through European empires; and (3) the inauguration of the IR discipline in the west after the First World War. As a result, the main foundations of both practical and academic international relations are shaped by western perspectives.

With intensifying globalization after the Cold War, a better understanding of international relations, exceeding the limitations of Anglo-American or western worldviews was needed. This need for a more global IR immediately popularized a search for non-western alternatives. As a result of this, ruptures within the discipline and their profound impacts on the nature of the discipline have become more salient. One of the main issues that the literature has begun focusing on is the absence or exclusion of non-western voices from the discipline.

Even though the main discussions converge on the exclusion of non-western perspectives, this paper emphasizes deeper and more basic problems outside the western core preventing the periphery from participating in a global debate. The main question here is about whether the problem emerges out of the exclusivism of western IR or the absence of alternative perspectives. The main argument of this paper leans toward the second option and investigates the fundamental problems within the non-western periphery. Non-western IR has serious problems of productivity and suffers from an epistemological incompatibility with the western core, which exacerbates the already existing problems in the periphery.

This paper takes the Turkish example and tries to outline such problems, based on the assumption that these problems are common in other parts of the world as well. This article can be considered a first step to discovering the problems in the periphery, and in order to reach more generalizable conclusions, similar research has to be done in different countries. A comparative analysis would be invaluable in this case; however, such an endeavor exceeds the limits of this article. The Turkish example is however especially significant for two main reasons: (1) Turkey is a country where western and non-western encounters have a long history. These two perspectives blend at times and clash in others; and (2) Turkey is geopolitically in a unique position where original perspectives can emerge, as it is situated in the middle of politically active regions, such as the Middle East, the Balkans and the Caucasus. Therefore, as the paper claims, Turkey stands out as one of the best places to observe and analyze the interactions between western and non-western perspectives. One can also find there both emotional and rational bases for all the problems emerging from such interactions. For these reasons, Turkey appears to be one of the best candidates to start investigating the interactions between the core, the periphery (or western and non-western) and the outer periphery, and the consequences of such interactions for the discipline.

First, the multi-dimensional fragmentation of the discipline, which leads to multiple worlds of IR with no communication with each other, is outlined. Since it is almost impossible to create a truly international or global IR without first grasping and mapping out these problems, and then finding out ways to overcome them, a comprehensive understanding of such issues is imperative. Unless the periphery solves its problems outlined in this article, the discipline will remain a primarily western science. The current literature mainly focuses on the division of a western core and a non-western periphery, and the core’s exclusion of the periphery. While doing this, it neglects or fails to observe more basic and crucial problems within the periphery, and especially its heterogeneous character. In that sense, by taking a look at the world of the periphery, this paper tackles an issue that is mainly neglected by the literature.

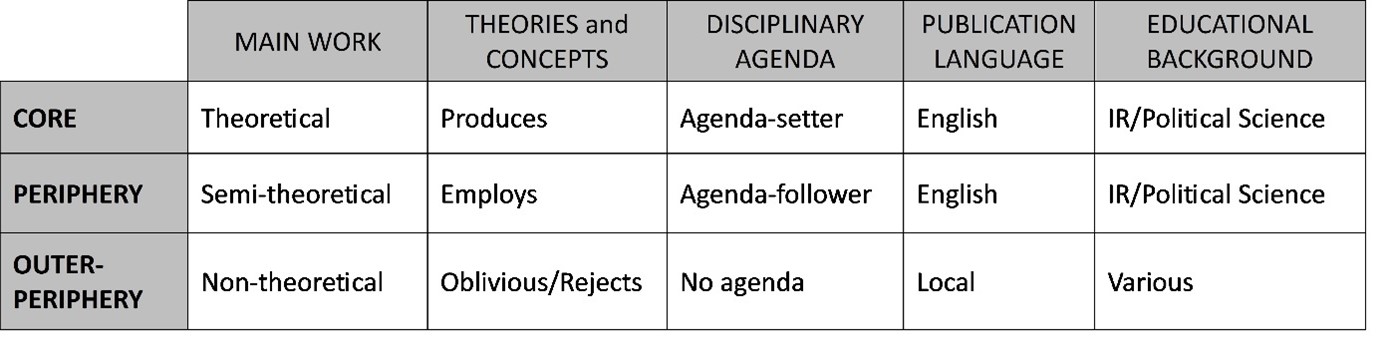

Despite its monolithic appearance from the outside, with its heavily western and specifically Anglo-American character, the IR discipline is highly fragmented within itself, to the degree of disintegration. Here, this fragmentation is viewed in three dimensions: (1) within the core;[iii] (2) between the core and the periphery; and (3) within the periphery. This paper, after reviewing the nature of the first two, focuses on the third dimension of fragmentation, which is between the periphery and the outer periphery. The concept of the core refers to mainly mainstream/western parts of the discipline where all the major publications are made, theories and concepts are produced, and the global agenda setting occurs. The periphery on the other hand, follows the core’s agenda, uses its theories and concepts, and provides case studies and practical field data for the core’s theories.

The main focus of this article, the outer periphery, on the other hand, is completely disconnected from both the core and the periphery. The outer periphery shows no interest in abstract concepts or generalizable explanations, has no clear agenda to follow, and focuses on more practical political problems, some of which are not even international. The outer periphery, compared to the other two, is less coherent and more diverse. More importantly, the outer periphery is almost invisible to the discipline because of its qualitatively different publications and disconnectedness from the rest. The variety and diversity of the scholars in the outer periphery in terms of their educational background and research topics might look like an advantage at first glance; however, disconnectedness even among the outer periphery scholars, poses great challenges for both the outer periphery and the rest of the discipline. It might even be an overgeneralization to call them the outer periphery as there is no common ground to conceptualize them as a whole. However, for the purpose of drawing attention to a group of mostly unnoticed problems in the discipline, this paper calls the remaining parts of the discipline outside the core-periphery division, “the outer periphery”.

It also needs to be emphasized that the term “outer periphery” refers both to above-mentioned structural and institutional problems and also to a certain mentality. It is not a geographical or a spatial term, but a mental positioning. Therefore, it can exist even within the west, which, by definition, is perceived to be the core. The studies in the outer periphery, as will be discussed in the following pages, can be called “quasi-IR” or “pseudo-IR” because of their lack of content or irrelevance. In any case, it would be fair to state that, the IR in the outer periphery is based on a completely different mindset.

Table 1 - A Comparison of the Core, the Periphery, and the Outer-Periphery

The first fragmentation, within the core, started with the so-called “Great Debates” and multiplication of paradigms. Added to its interdisciplinary nature, these debates between different paradigms created a fragmented discipline, where different paradigms constructed different images of international relations without making any contributions to each other’s understanding of the international phenomena. They almost spoke different languages, making communication ever more difficult and aggravating the problem of multi-disciplinarity. In some cases, such differences turned into antagonistic clashes similar to ideological battles. Scholars coming from different disciplines and sometimes with disparate paradigms further created their own niches within the discipline without any meaningful channels of communication. Lake calls this “academic sectarianism” and “theological debates between academic religions”.[iv] To some, such debates did not even take place, and debating schools of thought were retrospectively imagined for pedagogical purposes.[v] In reality, there were different worlds of IR apart from each other, and the discipline was fragmented into different paradigms and methodologies. Disintegration of the discipline into entirely disjointed schools focusing on different aspects of international phenomena, at certain times, made even the very existence of the discipline questionable.

The second dimension of the disciplinary fragmentation is between the core and the periphery, or the west and the non-west, which is the main point of departure for this article. Unlike the first dimension of the fragmentation, the division between the core and the periphery runs against the nature of the discipline, and affects it in negative ways. The first dimension emerges out of the multivariate nature of the international phenomenon. Therefore, the diverse nature of the discipline is easily understandable (and perhaps even a desirable thing[vi]), because the subject matter of “international” requires multi-disciplinary and multi-paradigmatic approaches, and one can argue that multiplicities and plurality are necessary for the discipline to develop.[vii]

However, unlike the existence of multiple paradigms, the core-periphery or the west-non-west division is not natural, and leaves the discipline incomplete and prejudiced, causing epistemological and ontological problems. Since international phenomena require a multiplicity of perspectives, the rift between the core and the periphery deprives IR from certain perspectives, which are undeniably important parts of the international practice. An absence of perspectives from the periphery leaves the discipline in an incomplete stage. The discipline might be heavily shaped by western perspectives; but international practice is not solely western. There are parts of the world outside the west whose perceptions and interpretations of international events have substantial impacts on international relations. Adding these outsider perspectives and interpretations might help us to have a better understanding of international relations. Otherwise, western theories might not be able to understand or they might simply misinterpret other parts of the world.[viii] Said’s criticism of orientalism is a good example of this.[ix] Even though more recent critical and post-modern theories bring up this issue of silenced perspectives in world politics to the agenda of the discipline, there are no concrete results which suggest that a non-western alternative IR is coming into existence. Moreover, some attempts to create alternative and unique non-western approaches show that they are epistemologically and methodologically not much different from the western examples, and in some cases, they are arguably inferior to them, especially because of the lack of critical perspectives.[x]

The division between the core and the periphery (non-western, alternative) can be interpreted from mainly two interrelated perspectives. The first one focuses on the fact that the periphery is completely absorbed by the core and serves the core’s agenda; and the second perspective emphasizes the potential of the periphery to develop alternative views and theories. Methodologically and epistemologically different from each other, two different worlds of IR (western and non-western) appeared in the second half of the 20th century. While the western “core” produces theoretical arguments and concepts, the non-western “periphery” provides empirical evidence for these theories. In that sense, the periphery does not produce its own conceptual framework (or paradigm), but feeds into the core’s theories. Aydınlı and Mathews call this “the unspoken division of labor” in the discipline.[xi]

As to the second perspective, there are alternative views in the periphery, which are different from that of the core, but they are either silenced, or need discovering. If the periphery is silenced, then this division is not merely an academic issue, but also has power/political roots and consequences of domination. As Shilliam has pointed out, “(t)he attribution of who can ‘think’ and produce valid knowledge of human existence has always been political.”[xii] According to this view, the parts of the periphery that reject to join the core’s agenda are excluded from the global discipline and silenced. This deprives the global core of the potential of developing original concepts and theories. According to Aydınlı and Mathews, the sharp divide between the core and the periphery needs to be bridged, and one way of doing this is homegrown theorizing, where the periphery makes its original contributions to the field.[xiii] This implies a rich and undiscovered potential for IR theories, and therefore the division between the core and the periphery, in which the latter keeps its own originality without being assimilated into mainstream theories, can be a source of new theories, rather than a problem. However, before building bridges and making healthy connections, an awareness of the problems on both sides is needed. This brings us to the third dimension of the disciplinary fragmentation, which is within the periphery itself and overlooked by most of the IR literature.

The current literature, while focusing on the core-periphery divisions, fails to notice that there is another aspect to the disciplinary fragmentation within the periphery. There are also cores and peripheries within countries, and in most cases, the divide within countries is deeper than the one between the global core and the global periphery. Aydınlı and Mathews talk about a periphery of the periphery as well.[xiv] This paper prefers to call it “the outer periphery.” The outer periphery, as a result of its socio-economic disadvantages, is not easily noticeable by the core, especially because it does not speak the language of the “global” IR, which is English, and does not participate in the core’s conferences. The texts produced in the outer periphery are mostly in native languages, and published mostly in local journals. Such publications are largely disregarded by both the global core and the global periphery for several reasons. This paper tries to reveal certain characteristics and problems of the outer periphery and their meaning for the search for a more truly international discipline.

There are considerable efforts and debates about the globalization of IR to make it less western oriented. Ironically the globalization and universalization of IR still reflects its western centric perspective. Contrary to common assumption, the western-centric nature of IR, or not enough globalization, seems to be more of a problem of the core, rather than that of the [outer]periphery. The search for new theories and perspectives turned the face of the western core to the non-west, while this search is far from meeting the expectations because of the fundamental and unnoticed problems of the periphery. From the periphery’s perspective, the biggest problem is not the lack of true internationalization, but growing fragmentation of the discipline to such an extent that it is assimilated by “other disciplines”. As will be discussed in the Turkish example, this fragmentation, especially at the outer periphery, blurs the disciplinary boundaries, epistemology and identity, and reduces it to a open field shared by all other disciplines. At first, such urgent problems emanating from the outer periphery are to be identified and then solved. As seen from this perspective, the discipline is not globalizing, but further fragmenting and creating different worlds of IR.

The differences and fragmentations especially outside the core and the problems of the outer periphery are generally neglected by the literature. The literature on divisions and fragmentations within the discipline usually focus on paradigmatic plurality within the core in conjunction with the existence of a periphery. This paper, while trying to scratch the surface of an unnoticed array of problems, also aims to contend that the periphery is much more divided and fragmented within itself, without any unifying disciplinary, methodological, conceptual, theoretical, or even educational common ground. Even though focusing on the Turkish example, this paper also assumes that most of these problems and characteristics of the Turkish periphery is not endemic to Turkey, and it is possible to find similar examples in other parts of the world.

Turkish IR is especially compelling because of the country’s historical background as a home to several multinational empires, and its pivotal geopolitical location as the focal point of the hotspots in contemporary international politics, such as the Middle East, the Balkans and the Caucasus. IR studies in Turkey have a great potential to make significant contributions to global IR, if they can overcome the problems that have been discussed below. Paradigms are heavily influenced by both historical backgrounds and the positions from where the international events are viewed. This makes Turkey’s possible contributions even more awaited and appealing.

This article looks at the division of the periphery within itself as one of the underlying conditions that curtails its potential for original contributions to the discipline. Like the global discipline, Turkish IR too is divided within itself. Although it remains as a periphery within the global discipline, there is also an outer periphery within the Turkish periphery, where publications, education and academic agendas are completely different, and there is no epistemological consensus about what “international relations” is, and why the IR discipline exists. Unlike the common conception, the periphery is more integrated with and attached to the core,[xv] while the outer periphery struggles with completely different and fundamental problems. In that respect, the real disparity is between the periphery and the outer periphery, especially because there is a sharp and ironically unnoticed detachment between the two.

The outer periphery’s problems are more fundamental and ontological. Mainly for that reason, the periphery has minimal connections with its outer periphery. Publications, as well as education, are in English at the periphery, while these activities are conducted mainly in Turkish at the outer periphery. The scholars from these two parts of IR participate in different conferences, publish in different journals, and do not interact academically, aside from a few exceptions. Since their scholarly communication is in different languages and they have different perspectives of IR, the periphery is unable to notice the problems of its outer periphery, leaving it to its own problems. Even though the outer periphery seems almost non-existent to the core, its effects on the discipline are concrete and very much real. Before investigating its influence over the discipline, a brief introduction to the world of the outer periphery is needed.

IR departments in Turkey are organized in two different ways, both in the periphery and the outer periphery. The first group of departments are called International Relations (IR). The second group is organized in a more interdisciplinary way and called Political Science and International Relations (PSIR). Even though both departments are open to scholars from other disciplines, PSIR departments are more heavily dominated by political scientists. A general overview indicates that in both departments, the range of studies are so wide that some of them are difficult to identify as IR, especially at the outer periphery.

The discipline at the periphery is so divided within itself that it has became a field completely open for all social disciplines, with no common theoretical or conceptual base. This unruly and chaotic invasion of the field by scholars who have no education in IR, international history, or even political science, further disintegrates the discipline. At first glance, opening the IR field to other disciplines can be interpreted as a contribution to the field; however, to receive contributions, a conceptual common language is needed. IR departments in Turkey hire individuals whose educational backgrounds range from physics to biochemistry to several departments of the faculties of education, and from theology and linguistics to Turkish Republican History. Notably in the outer periphery, a significant number of scholars are not required to have an IR or political science doctoral degree to be appointed in the IR departments. It is logically arguable that scholars from other disciplines can relate their academic interests to international relations and contribute to the discipline. But a closer look at such studies reveals that this is not the case, and some of them are not even remotely related to the field.[xvi]

Most of the scholars who are from other disciplines are especially historians, retired diplomats or military personnel who hold doctoral degrees from a variety of different fields. Most historians are Republican Era Turkish historians, who study Turkish political history from the early 20th century. Among these, almost none focus on diplomatic or international history, and most of them concentrate only on Turkish or Ottoman history. The overall picture indicates that there is a considerable number of scholars in the field of IR, who have no education or specialization in the discipline, yet they continue to teach IR courses, and publish “IR” articles and books.[xvii]

For a factual demonstration of the underlying problems, first, I selected 30 different IR departments which can be considered as the outer periphery. These universities employ 223 scholars holding different levels of professorship positions. In the Turkish academic system, qualification for associate professorship is an especially crucial stage for professional specialization, perhaps even more so than the doctoral degree. In the outer periphery there are a significant number of scholars who received their associate professorship from unrelated fields. Since the information about the associate professorship field is not publicly available, it was not possible to draw an exact number. However, the main database concerning the university departments (YÖK Atlas) has information about the departmental scholars’ educational backgrounds.[xviii] A general overview of the first group of departments (IR) shows us that out of 223 scholars, 54 have no degrees in IR, political science or regional studies, in any of their educational background (undergraduate, masters and doctorate). Additionally, 58 of these scholars wrote their doctoral theses in fields and topics other than IR or political science.[xix] In these departments, the number of scholars who hold a doctoral degree in IR or regional studies (Europe, Middle East, Asia, etc.) is 133, which makes roughly 60 percent of the total number.

The second step was the investigation of the second group of departments (PSIR) to compare it with the first group (IR). This overview also has a similar outlook with the previously examined IR departments. The selected 19 outer periphery departments employed 143 professors (full, associate and assistant). Among them, only 65 had their doctoral degrees in IR or regional studies, which is around 45 percent of the scholars who are employed in PSIR departments. In total, combined data indicate that, out of 366 scholars who are employed in these departments, only 198 have doctoral degrees in IR or regional studies. In some departments, not surprisingly, the IR scholars are in the minority.

Disciplinal identity is mainly formed at the undergraduate level, as all the fundamental courses of the discipline are taken at that level. From that perspective, a closer overview of the fields of undergraduate education of these scholars, who are employed in the departments and carry the title of IR professor, is also needed. For this, a count of professors who graduated specifically from the IR departments has produced similar results as their doctoral degrees. Out of the sampled 366 faculty members employed in IR and PSIR departments, only 180 had their undergraduate degrees in the field. Therefore, it can confidently be asserted that in the outer periphery, the field is shaped and dominated by other disciplines, some of which are not even related to the IR discipline, and in certain cases leaving the IR scholars in minority in their departments. Dilution of these few IR scholars into so many different IR departments, reduces the possibility of academic collaboration, interactions and discussions, and impairs joint research efforts. This inevitably reduces the levels of academic productivity, creativity, and quality, by diminishing the opportunities for professional development.

Further research is needed on the issue of educational background of the scholars to reveal the seriousness of the problem and its consequences. Most publications concerning the general structure and problems of IR academia[xx] fail to note the problem of educational background, and take it for granted. However, this is an issue that negatively affects the quality of education and publications in the outer periphery, and corrupts whatever potential there is for original contributions to the field. What makes the detection of this problem even more difficult and its grave consequences unnoticeable is the interdisciplinary character of the IR field. IR is inevitably, and should be, open to contributions from other fields. However, to call this a contribution, the discipline should be able to define its main premises. Without a disciplinal identity, IR turns into an unorganized market place where nobody knows what they are searching for. Under such conditions, potential contributions can never be realized. This mixture of disciplines without any common conceptual, theoretical, paradigmatic or problematic concerns turns the discipline into a multi-disciplinary non-discipline, or an empty field to be occupied by outlier academics who do not fit into their own disciplines. Opening the discipline to scholars who have no knowledge of the literature, theories and concepts, with an attitude of “everything goes”, reduces the discipline to an absolute nothingness.

This blurs the general understanding of what the discipline is about, the main concerns, research goals, and educational content. Therefore, in the outer periphery, there is no clear understanding of what IR is and what it does,[xxi] let alone the capacity to make theoretical or conceptual contributions to the discipline at any level, national or international. For making meaningful contributions, the discipline needs to build a common academic ground, and there should be at least a minimal common understanding. Therefore, to solve these issues within the outer periphery a serious debate about the epistemological nature of the discipline is needed.

From this general overview, one more point can be deduced and needs to be emphasized. The concepts of the periphery and the outer periphery in this study, unlike the common understanding, do not refer to a geographical location, but a certain set of problems and a mentality shaped by it. Just as the general mention of the west (core) and non-west (periphery) implies a location, the outer periphery is inaccurately understood as a geographical location, usually referring to the universities and departments in the rural Anatolian towns outside Ankara and İstanbul. The spatial understanding of these concepts is misleading and veils the growing problems within the periphery. The periphery is a set of structures that might exist anywhere, even within the west. In its essence, even the older universities in Ankara and İstanbul might as well be a part of the outer periphery.

The periphery, focusing on its status in relation to the global core, neglects and fails to notice substantial problems within. Therefore, any solution that deals with the problems of the periphery and its status vis-à-vis the core, has to identify and deal with the problems of the outer periphery as a starting point. Identifying the underlying issues, developing an awareness, and then solving these problems are crucial both for a better understanding of the world of the outer periphery and for its integration with the rest of the discipline. This also might open new channels of constructive communication and exchange of views between different parts of the discipline, which might then establish concrete bases for a global IR. It would be overly optimistic to expect the periphery to make original contributions to the core without solving its domestic problems.

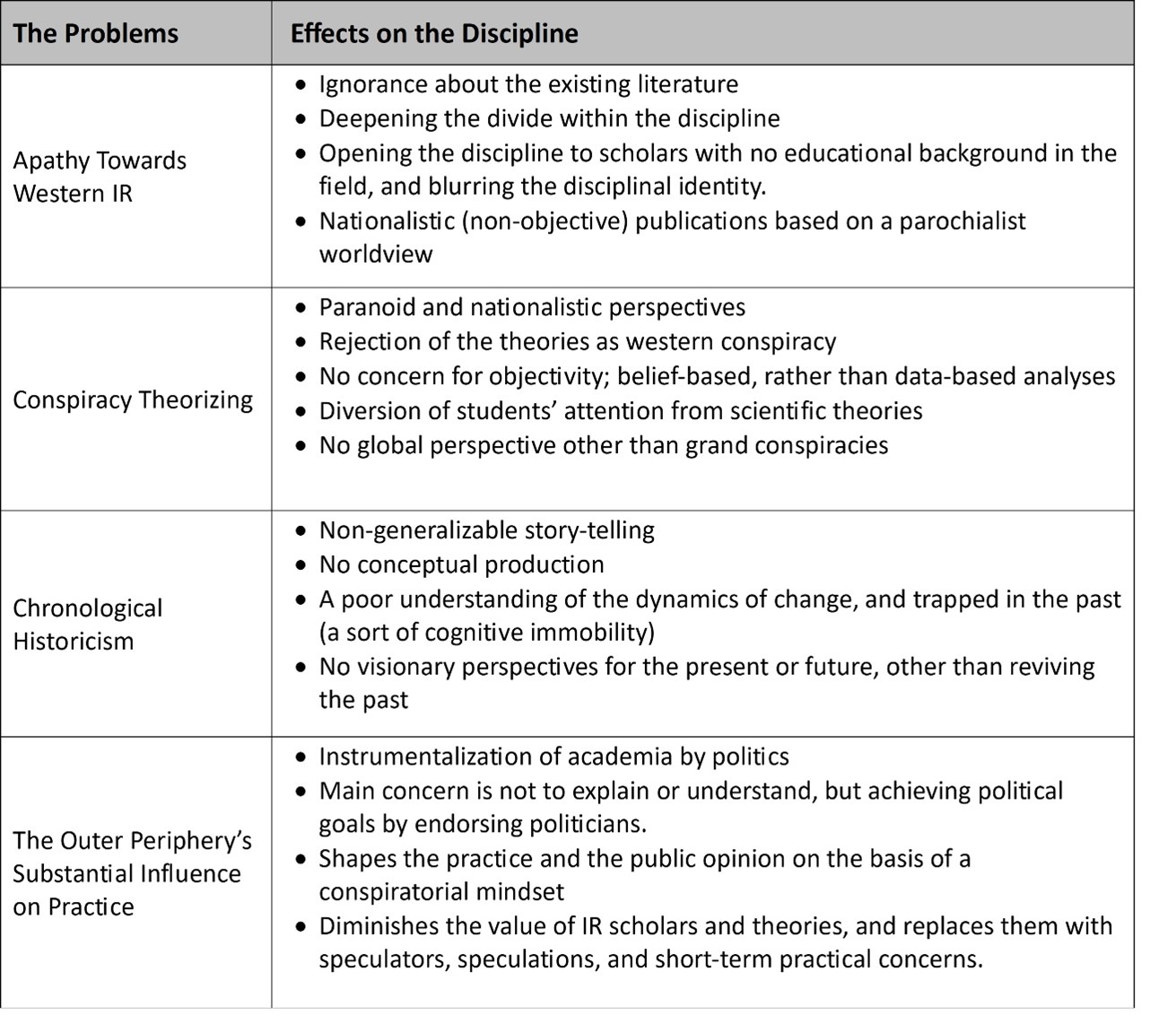

In outlining the main characteristics of the Turkish outer periphery and how it affects IR studies in Turkey in general, this paper elaborates on four typically degenerative issues as an extension of its structural problems. The term degeneration refers to the detachment of the outer periphery from the periphery and its epistemological disengagement from the rest of the discipline in a way that prevents it from producing good quality publications. The most visible outcomes of this are a loss of disciplinal identity; instrumentalization of the discipline by political actors; and production of speculative, non-academic, highly politicized studies, heavily influenced by short-term daily politics. In order to extract an original paradigm out of these unique conditions, the nature of these interrelated problems needs to be fully recognized.

The first problem is the ignorance of or apathy towards the knowledge produced in the core, which leads to completely different kinds of studies. This emerges as a reaction to being excluded and unable to participate in the discourses at the core or periphery. At the end, this turns into a reaction that can be called “reverse orientalism,” where the outer periphery rejects most of the knowledge and theoretical constructs of international relations produced by the core. Scholars are not familiar with, or care to know such knowledge. The second problem is also radically different from the core IR, which can be called chronological historicism. Despite the fact that IR theories are criticized for their ahistoricism in the core, the outer periphery struggles with the problem of heavy chronological historicism. The third major problem is conspiracy theorizing, or conspiracy as a paradigm. The conspiracy paradigm is merely based on and emerged from speculative explanations about international politics, requiring no previous theoretical knowledge or concrete data. The first problem of rejecting most knowledge produced in the core, is that it creates conditions prone to speculative explanations of international relations. The fourth and final problem illustrates the negative effects of the outer periphery when it becomes the practical mainstream. Since the scholars of the outer periphery are more in number, they have a quantitative advantage especially in shaping public opinion and foreign policy practices. In this way, the periphery brings its own problems, paradigms and perspectives to the practical politics and starts shaping practice.

Now, we can turn to these four issues of the outer periphery, emerging out of this general structure, and requiring the utmost awareness. These issues prevent academic development of the discipline and its true globalization, and reinforce and reproduce each other through employment policies and publication outlets, all of which can be a subject of comprehensive research projects in the future. Here, we will try to identify them briefly.

The literature on non-western IR focuses more on the west’s gatekeeper position and the obstacles for the periphery to join the discipline with its own alternative perspectives. However, there is another side to this coin. There are parts of the periphery that reject joining (or show no interest in joining) a dialogue within the rest of the discipline, namely the outer periphery. Contrary to the common assumption that there is a deep rift between the core and the periphery, these two are actually relatively well integrated. The outer periphery, on the other hand, is qualitatively different from, and also usually invisible to both. This invisibility is returned back as a rejection of both by the outer periphery.

Though Aydınlı and Mathews emphasize intellectual dependency and theory importation as major problems of the periphery,[xxii] this issue looks completely different from the outer periphery. One of the distinct characteristics of the outer periphery is its disinterest in the theoretical knowledge produced by the core. Emanating from the structural conditions at the outer periphery, three main reasons can be identified for this disregard. The first one is that there are a considerable number of scholars who have no educational background in IR, no knowledge of theoretical debates or basic concepts, and have no interest in learning them. This leads to the second reason, where such scholars, despite their lack of educational background in IR, seek acceptance and recognition in the discipline. Since it would be strenuous to make up for the lack of accumulated knowledge, the easiest path is a complete rejection of it. Linguistic shortcomings, limiting the access to the literature produced by the core, also contribute to this attitude. This predicament also interacts with the rising tide of nationalism, where local languages are praised in place of English. This is also related to the third reason, which is ideological. Lack of knowledge in the field, finds an ideological excuse for not studying the existing IR literature.

In certain cases, all western knowledge is rejected, because it is seen as a device of domination, imperialism, colonialism, and hegemony. It is viewed by the outer periphery as a sort of intellectual corruption and colonization of the minds. This includes IR theories, as they shape peoples’ perspectives of international politics. Some scholars, in their theory classes, do not teach theories, and claim to teach students how to think beyond the boundaries drawn by the western literature. Even though this might seem like a legitimate claim, in practice, it cannot be achieved academically without teaching/learning first what kind of knowledge has been produced in the west. Furthermore, in order to replace old perspectives with new liberating ones, a logical expectation would be the construction of new concepts or theories, which are also yet to be generated.

The decolonization of IR is a legitimate goal in creating a truly globalized discipline.[xxiii] Therefore, the debate needs to focus on how it should be done. Even though there are calls for revolutionary approaches, the methodology of decolonization should be based on a multiplicity of perspectives to overcome the western parochialism that has dominated the discipline since its establishment. A complete rejection of western theories leading up to a complete destruction of the IR discipline would not serve that purpose, but open up the whole field to a purposeless occupation by other disciplines, as happens in the outer periphery. Even when the whole methodology of decolonization is revolutionary, the main goal has to remain as accumulation of knowledge, not an anarchist revolution which totally ignores the existing literature. Decolonization can only be fruitful when the whole process is based on a dialogue where the western origins are questioned and re-examined by its alternatives, rather than its total rejection.

In order to decolonize IR thought, first a full understanding of the existing western literature is required; however, this is the exact ingredient that is missing in the outer periphery. Without this, the whole effort turns into a fruitless nationalistic rebellion against the current discipline and a mere rhetorical support for the ultimate goal. After all, raising an awareness about the problems and the consciousness of non-western IR are possible only through the knowledge of previous theories. Without knowing what is criticized, the claim of establishing alternative perspectives is baseless.

The political history and the current atmosphere in countries inevitably shape the nature of the development process for homegrown or alternative theories. As an extension of the political atmosphere in Turkey, neo-Ottomanism is a very popular ideology among outer periphery scholars. Neo-Ottomanism implies an admiration of an idealized Ottoman past, a longing for its superiority against the west and a reaction to the modernization process. This imperial nostalgia shapes the way people perceive and interpret international relations in Turkey, especially in the outer periphery. From that perspective, anything the west has produced is an extension of its imperialist past. This also feeds into an illusion of greatness, where as an heir to the throne, Turkey has regional and global responsibilities to reestablish the just order of the Ottomans, which was destroyed by western imperialism. The motto of “the world is bigger than five” is widely used by the outer periphery scholars.[xxiv] This motto is not just a simple criticism of the international/UN system, but a way to question Turkey’s absence among the permanent five members of the UN Security Council (P5).

Combined with popularization of the views of Islamic/Asian revivalism in recent decades, the political and academic ecosystem has created a new paradigm, which some scholars call “reverse orientalism.” It is not peculiar to Turkey, and its examples exist all across Asia, especially in the Arab world, Japan and China, sometimes under the rubric of “Asian Values.”[xxv] Reverse orientalism is a spinoff concept of orientalism, coined by Edward Said. Even though Said warned that “the answer to orientalism is not occidentalism,”[xxvi] with the tide of rising nationalism and anti-modernism, occidentalism, or reverse orientalism, has become the intellectual fashion in some parts of the Asian continent. In the Turkish case, having an imperial past, an idea of uniqueness of the country and its central position in regional politics, has led to a rejection of all western impositions, whether they be political or intellectual. This has fed into the idea of some kind of exceptionalism, with Turkey not needing any western ideas in conducting relations with other countries, and being the last bastion of defense against western imperialism. Again, in Said’s terms, this has led to “the seductive degradation of [the western] knowledge.”

A search for a non-western IR theory inevitably starts with a critique of the existing western literature, but this search has several pitfalls. The first one is to reproduce the criticized falsehood, namely the parochialism of western IR. Despite the fact that reverse orientalism emerged as a reaction to an orientalist parochialism, when turned into a political project, this reaction has ironically created a new sort of parochialism. The second danger is related to the first one. The rejectionist parochialism creates a sort of willful ignorance, proudly not knowing and not wanting to know western theories. Any attempt to produce new knowledge of IR based on this binary reactionism is doomed to be artificial and unsustainable, which cannot be considered a contribution to the field, and this seems to be the case in the outer periphery. To avoid this binary western-non-western exclusionism, some suggest the term “post-western IR” to define the search for a more inclusive approach.[xxvii]

Conspiracy theories are everywhere, but when it is in academia it is a different story. Studying conspiracies and analyzing conspiracy theories might well be a part of academic studies, but the real problem emerges when the whole world of international relations is viewed through the prism of a conspiratorial mindset. Therefore, the real problem in the outer periphery is the paradigm of conspiracy. This becomes a problem for the outer periphery especially through IR scholars who have no IR education. The lack of an educational background leads these scholars to simplistic and speculative accounts of international relations. It is possible to identify three main reasons for this problem: educational, ideological, and practical. The problem of educational background has already been discussed in the previous section. Rejectionism of all previous western knowledge and literature is highly convenient for such scholars, as it levels them with IR scholars and puts them on equal footing. Once educational background is removed from academic qualification standards, IR is reduced to a layman’s field of analysis. The easiest and most popular way of doing such analyses is through conspiracy theories, which require no education, but only imagination.

The second reason behind the spread of conspiracy theorizing is ideological. Anti-westernism as a rising ideology, combined with neo-Ottomanist perspectives, leads to a demonization of the west, from where it is assumed that all the malfeasance, sedition and wrongdoings emanate.[xxviii] Explanations relating to any dimension of west-non-west relations from such a world view inevitably leans toward conspiratorial approaches. This conspiratorial paradigm disguises itself as anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism.[xxix] Unfortunately, the conspiracy mindset has become the main perspective in the outer periphery, sometimes openly, and at other times as an underlying mentality.[xxx] Some even see IR theories as part of a wider conspiracy, which are ordered by western governments to serve their states’ national interests, and/or legitimize US supremacy.[xxxi]

The third reason for conspiratorial explanations is practical and political. IR is seen by most outsiders as a prestigious field to get media recognition first and then make a transition to active politics in Turkey. There is no better way than conspiracy theories to get media attention. For similar purposes, there are also examples of personal disguise where non-IR scholars present themselves as IR experts on media and make foreign policy analyses, or publish books on international politics and Turkish foreign policy.[xxxii] The real influence of the outer periphery comes from its simplistic/conspiratorial explanations which give them an outstanding power of shaping public opinion. The public attention is captured more by simple explanations, which require no previous knowledge about the subject matter, and easily stir emotional responses mixed with nationalist feelings, such as fear and anxiety. Therefore, people and politicians are more effectively influenced by conspiratorial explanations, rather than sophisticated analyses of international relations.

There are also some scholars who choose conspiracy theorizing as a career path. Erol Mütercimler, took issue with western imperialists monopolizing the field of conspiracy theorizing, and argued that Turkey needed to produce its own conspiracy theories to shake that monopoly. As a self-declared conspiracy scholar, he undertook the mission of raising conspiracy theorists.[xxxiii] This is the conspiracy theorist’s way of decolonizing the non-western minds and searching for alternatives.

However, conspiracy theories, because of their paranoid nature are not a healthy way of analyzing international relations, or formulating policies. Unless it is reduced to merely a brainstorming exercise, conspiracy as a mindset harms the discipline, starting from the outer periphery and working its way inwards.

As we move away from the core, the conceptual and theoretical nature of IR fades. While the center of the core makes pure theory, the outer periphery only tells historical or current stories about world politics. The studies between these two extremes have a mixture of empirical and theoretical analyses, the ratio depending on the closeness to the core or the periphery. Therefore, while an issue of ahistoricism prevails in the core, a completely different problem holds sway in the outer periphery, namely, too much of history or sheer story-telling.

The main reason for chronological historicism at the outer periphery is the influence of the historian scholars in the IR departments (50 out of 366 sampled scholars).[xxxiv] Undoubtedly, history is an unavoidable part of IR; however, the main concern from our perspective is the type and quality of historicism. In Turkey, history in general is not studied thematically or in a conceptual way. The main methodology is a detailed investigation of archive documents and sometimes merely a translation of them from the Ottoman language into modern Turkish. For IR, this kind of event-centered historicism can only offer raw materials to the discipline, but cannot construct new theories. IR needs much more than raw materials to acquire meaningful contributions from the historians. History is most valuable for IR when it is combined with concepts and theories, allowing us to travel into the historical depths of current relationships and to see how things change or survive over time. The English School is a good example of this.

However, instead of making contributions, the historians aggravate some of the problems such as the conspiracy mindset. Trapped in the past and not making analytical deductions, the historians in IR interpret current world events as they were happening in the past, and emphasize the secretive nature of diplomacy and inter-state relations based on concepts like imperialist conspiracies. One of the main concerns of IR is to be able to understand the dynamics of continuity and change, and make sense of a changing global structures. The historicism in the outer periphery causes a sort of obsession with the past, not being able to move forward mentally and interpreting the present events as if they are happening in a bygone world, thus experiencing a sort of “cognitive immobility”.[xxxv]

Most of the articles published in the outer periphery are chronological narrations, with no generalizable proposition.[xxxvi] It is obvious that this kind of writing cannot go beyond presenting the necessary raw material for theory production. This is one of the main and the most challenging problems at the outer periphery. It is challenging because this chronological methodology reproduces itself through student assignments and theses at all levels of undergraduate and graduate education. This is one of the reasons why the outer periphery cannot go beyond producing factual information and produce abstract, generalizable theoretical knowledge, which could be a more meaningful contribution. For a productive integration between the core, periphery and their outer companion, first they need to speak the same language, which consists of the approaches, concepts and theories.

There is no doubt that there are varieties of history, which can roughly be classified into two main categories for our purposes here. The first one focuses on particularistic details of certain actors or events, and the second one tries to analyze the underlying processes, environments or conditions surrounding such actors or events, and puts them in a context. IR needs more contextualizing works of history, rather than ones that present the particularistic details without their larger background conditions. According to Friedrich Meinecke, historiography until the Enlightenment focused on the first kind, and later it “expanded its horizon to include supra-individual causalities and processes.”[xxxvii] Even though both kinds of methodologies are needed within the discipline of history, for IR to benefit from it, a sort of contextualizing historical knowledge, going beyond the chronological storytelling, is needed. Contextual history is especially significant for the peripheral IR, because the counterpart of the ahistoricism at the core is the chronological narrative historicism at the periphery, both limiting IR’s horizons and undermining its potential. Unless this is achieved in one way or other, IR, rather than benefiting from history, will turn into a kind of chronological narration without a purpose.

Actually, post-western or globalizing IR largely demand contributions from historians. Alternative histories are in urgent need for enrichment of the existing theories (a sort of decolonization), and to lay the ground for new theories. The traditional narrative history, focusing on the details of certain documents, actors, or events, offers no help for that purpose. Without taking the context into account, a detailed narration cannot reveal the relations of domination and colonization. The main task of the historian from the IR perspective should be to reveal such contexts, so that alternative theories can emerge. However, historians of the outer periphery, not having any awareness about the problems in IR, are also not attuned to such needs. Most publications in the outer periphery are historical in nature; however, the main concern of these historians is more of their personal academic advancement through increasing the number of their publications, rather than making contributions to the discipline. Even though they are employed in IR departments, some still feel affiliated more with history than IR. Most such historians are not even aware of the discussions of a globalizing IR and the contributions that they are expected to make.

All these problems might be deemed inconsequential to an outside observer, especially because an outer periphery with such basic problems is not expected to make an impact on the discipline, or change its nature. However, the quantitative weight of the outer periphery grants it a significant clout in shaping the discipline. The number of periphery scholars who are in communication, or debating the state of the discipline with the core, is a small percentage of the number of scholars at the outer periphery. Out of 118 universities with IR or PSIR departments, over 100 can easily be considered as outer periphery departments.

Another issue is the availability of publications for the students. Most of the students have access only to IR articles written in Turkish because of their linguistic disadvantages, which deprives them of benefiting from most core publications. Therefore, the IR literature in Turkish, mostly produced in the outer periphery, sets the example and the standards for new generations of IR students and scholars. While the core/periphery scholars meet in academic conferences with their international partners, the outer periphery scholars form their own conference circles within Turkey, and they also stay in close contact with politicians and media channels. This last point is especially significant since the outer periphery shapes political practice, which is the subject of research for all, including the core. This makes the outer periphery the mainstream.

As the core and the periphery work in their ivory towers, the outer periphery affects the real world and influences policy. “The periphery-outer periphery disengagement” pushes the latter for a symbiotic existence with practical politics.[xxxviii] The attraction of politics to IR scholars is undeniable. As Stanley Hoffmann says, IR is more about practical issues, and scholars tend to play the role of advisers in world politics. Since the seat of the world government is empty, they either try to transcend conflictual state policies at the national level and make systemic analyses, or advise national policies. For that reason, “scholars are torn between irrelevance and absorption.”[xxxix]

Overall, the general approach at the outer periphery is more practical and less theoretical, therefore more partial and biased, especially against the west. The main goal is not an analytical understanding of international politics, but developing supportive arguments for government policies to promote their “national interests”. These practical concerns, combined with conspiratorial explanations, make the outer periphery a shaper of public opinion as well. As a result, while the outer periphery unites with practical politics and creates its own epistemological world, the rift within the discipline further deepens.

Table 2 - The Problems in the Outer Periphery and Their Degenerative Effects on IR

It is important to understand the problems of the outer periphery because they shape perceptions, behavior, policies, and relations in the real world, producing tangible consequences. In a sense, the world (especially outside the western domain) that IR scholars try to explain and understand is defined considerably by the outer periphery. Theories based on “western rationalism” might fall short of fully understanding a world that is shaped by a different sort of mindset. Perhaps one of the most concrete and striking examples of this is the rising anti-western emotions in Turkey. This has occurred despite the fact that the country has been a part of the victorious western alliance since the beginning of the Cold War. Instead of taking advantage of the victory, Turkey, especially in recent decades, has chosen to be in opposition to the West, and has not benefited from the Cold War victory, not even as much as the losing Eastern Bloc countries. The odd developments in Turkish foreign policy could be a subject for another research article; however, it is possible to conclude that the outer periphery scholars, with their conspiratorial and biased historical perspectives against the West, have had substantial influence on policy practices.

Aside from such practical concerns, it is also important to be aware of the fundamental differences between the studies in the core and the (outer)periphery, for establishing a truly global and all-inclusive IR. A better understanding of international relations is only possible with an epistemological common ground to combine all these differences into a coherent field.

This article has tried to reveal an aspect of a deep fragmentation within the periphery, which prevents the emergence of common ground for a disciplinary epistemology. Perhaps more importantly, these deep differences and problems do not reflect on the epistemological discussions in the literature, and thus curtail any potential for original contributions. However, in order to expand the discipline’s horizons and reach something that at least resembles a field with a global perspective, we need to understand the nature of the problems that prevent it from happening.

Therefore, what can be done about the western-non-western dichotomy? Inspired by Said, Chowdhry recommends a contrapuntal reading for reaching global post-western IR.[xl] A contrapuntal reading is about looking at the research subjects without compartmentalizing or polarizing the reading materials such as western and non-western, but taking them into account as a whole. This wholistic approach makes more sense to create a discipline that is more in line with its nature, and broadens our horizons. Solely trying to find an alternative to western IR would recreate the already criticized parochialism in the discipline. Therefore, a so-called non-western IR should be added to the existing literature, and not be established as a rejectionist alternative. This is a realistic danger, since some non-western scholars see all western knowledge as an agent of economic, political, and mental colonization. This creates a contest between different kinds of exclusionisms, instead of a more complete picture. As the movie Joker showed, even a comedically caricaturized villain might have a dramatically humane story behind it.

Similarly, a vision of west-non-west antagonism is a binary caricature of the actual situation, which neglects the history of knowledge-sharing and other exchanges between the two. A contrapuntal reading would require a consideration of both, and not a denial of each other. For that reason, instead of polarizing the exclusive perspectives, we need more multifaceted, fuller and more inclusive viewpoints, which require multipartite, overlapping, intertwined and mixed, instead of sterilized and pure categories. World history shows us that there is no “pure west” as a category, which is in fact an outcome of past cultural exchanges. In that sense, what is known as western philosophy or culture is a common heritage of human civilization. Therefore, efforts to find an alternative to it should not fall into the fallacy of reproducing new parochialisms.

From the peripheral perspective, the real issue seems not to be a deliberate exclusion of the non-west from the IR debates, but the structural problems that the periphery (or mainly the outer periphery) struggles with. Mearsheimer thinks that nobody prevents the non-western ideas or theories from being spread within the discipline. In his opinion, there is not much room for new theories, and actually there are none outside the established core.[xli] Mearsheimer is only partially correct in his statement. He is right that there is no substantial development outside the western dominated realm of theories. However, this does not mean that there is no potential for original ideas or perspectives to be theorized. It is instinctively obvious that there is great potential. However, the non-western periphery has to solve its own epistemological and methodological problems first, and it is not easy to overcome these deep-seated problems.

Despite all its disadvantages, the outer periphery, once its problems are solved, can make original contributions. For example, at first glance, conspiracy theorizing seems like a sort of unproductive reactionism based on bare speculation. Interestingly enough, however, as the periphery has struggled to make theoretical contributions, and is criticized for conceptual importing, the conspiracy theorists of the outer periphery have in fact produced original concepts, like “the deep state” which gained international recognition after it was coined in Turkey in the 1990s. Since it challenges the realist idea of a state as a unitary actor, the term led to the publication of several academic articles in the west.[xlii] The concept was popular in Turkey especially after the Cold War, referring to the secret and unaccountable parts of the state, operating behind the scenes, which shape government policies and are involved in clandestine activities within the country. This term shows us that conceptual and theoretical contributions might come from the least expected places, but to realize that potential, the IR discipline needs to integrate in more pluralistic and productive ways. For that integration, the periphery needs to solve the problems within itself, especially in the outer periphery.

In recent years, the Turkish university system has also exacerbated the divide between the periphery and the outer periphery by classifying public universities into two main categories: research and education. The research universities are mainly periphery universities, while the education universities are all outer periphery universities. This system, from the perspective of IR, on one hand encourages dialogue, integration and cooperation between the core and the periphery through joint projects and publications, while on the other hand, further excludes the outer periphery from global debates, turning them into introvertive educational institutions. This further deepens the rift between the periphery and the outer periphery, and severs the already weak ties between the latter and the global discipline.

It is not possible for the outer periphery to overcome these problems by itself. To solve them, more intimate engagement between periphery and outer periphery is needed. Only then can the periphery reveal whatever originality potential it has, avoid being assimilated into the core, make genuine contributions to the discipline and gain an equal status with the core. This is what both the periphery and outer periphery need urgently.

The search for alternative theories should be a sort of archeological excavation where previously unseen and covered facts and perspectives are revealed with the help of other disciplines. In order to interpret our findings, a common language is needed. This enterprise should neither be an exclusive one where only the west can come up with new theories, nor a reactionary one where all previous western knowledge is rejected and ignored. Perhaps then can we broaden our horizons, and puzzling developments, like the emergence of violent non-state actors and fragile states as exceptions and challenges to the assumptions of an international order based on the principle of sovereignty; rising state authoritarianism; and popularized longings to revive old empires (be it Ottoman, Russian, Chinese) with resulting conflicts, might start making more sense. For this, the balance has to be kept between a homogenizing universalism of the core and the shattering discipline in which the different parts are completely losing touch with each other, as happens in the outer periphery. A degree of homogenization is needed for a common language of communication, but we also need a moderate fragmentation to allow alternative perspectives. Perhaps this would give us more tools to understand the dynamics, directions and timing of the sweeping transformations, or unsuccessful attempts at the desired changes. Compared to what we know, there is a whole world to be discovered.

Notes

[i] Edward Hallett Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis. 1919-1939 (London: The MacMillan Press, 1946), 52.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Helen Louise Turton, “Locating a Multifaceted and Stratified Disciplinary ‘Core’,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 9, no. 2 (2020): 177-210.

[iv] David Lake, “Why ‘isms’ are Evil: Theory, Epistemology, and Academic Sects as Impediments to Understanding and Progress,” International Studies Quarterly 55, no. 2 (2011): 465-480; Peter Wilson, “The Myth of the ‘First Great Debate’,” Review of International Studies 24, no. 5 (1998): 1-16.

[v] Lucian M. Ashworth, “Did the Realist–Idealist Great Debate Really Happen? A Revisionist History of International Relations,” International Relations 16, no. 1 (2002): 33-51.

[vi] Nick Rengger and Mark Hoffman, “Modernity, Postmodernism and International Relations,” in Postmodernism and the Social Sciences, eds. Joe Doherty, Elspeth Graham, and Mo Malek (London: Palgrave MacMillian, 1992), 127-147.

[vii] K. J. Holsti, “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Which Are the Fairest Theories of All?” International Studies Quarterly 33, no. 3 (1989): 255-261.

[viii] Yong-Soo Eun, “Opening up the Debate over ‘non-Western’ International Relations,” in Going beyond Parochialism and Fragmentation in the Study of International Relations, ed. Yong-Soo Eun (New York: Routledge, 2020), 10-11.

[ix] Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

[x] Eun, “Opening up the Debate,” 17-18.

[xi] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations,” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 299.

[xii] Robbie Shilliam, “Non-Western Thought and International Relations,” in International Relations and Non-Western Thought. Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity, ed. Robbie Shilliam (London: Routledge, 2011), 2.

[xiii] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia,” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693-712.

[xiv] Ibid., 697.

[xv] Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Kristensen and Lohaus, in their research, found no substantial difference between core and periphery that resembles a “division of labor.” Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Peter Marcus Kristensen, and Mathis Lohaus, “The Global Division of Labor in a not so Global Discipline,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no 1 (2022): 3-27.

[xvi] If we need to name a few doctoral dissertations of some scholars who are employed in IR departments; “Ratlarda biber gazının (OC) bazı biyokimyasal parametreler üzerine etkisi [The Effect of Pepper Gas (OC) on Some Biochemical Parameters in Rats]”; “Şehir coğrafyası açısından Safranbolu-Karabük ikilemi [Safranbolu-Karabük’s Dilemma with Respect to Urban Geography]”; “Locational Determinants of Horticultural and Christmas Tree Land Uses in the Portland Metropolitan Area, Oregon: A Thunian Discrete Choice and Hedonic Land Values Approach”; “Eserleri ve fikirleri ile Cevat Rifat Atilhan [Thoughts and Publications of Cevat Rifat Atilhan]”; “XX. yüzyılda Tokat'ın sosyal ve kültürel yapısı [Socioeconomic Structure in Tokat in the Late 20th Century]”; “Türkiye sosyalist hareketinde Dr. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı'nın yeri: Tarih tezi ve din yorumu [The Place of Dr. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı in Turkish Socialist Movement: Thesis of History and Interpretation of Religion]”.

[xvii] The outer periphery also created its own outlets for such publications, some of which work in tandem with outer peripheries in other countries. Most of these journals are faculty or graduate school journals at the universities of the outer periphery. Scholars from the periphery rarely publish in those journals or publishing houses. The reason for this is the obvious concern with academic quality and images of these publication outlets.

[xviii] The information gathered for this article is based on the YÖK Atlas data from April-May 2023. “YÖK Atlas,” Yükseköğretim Kurumu, accessed date April 01, 2023, https://yokatlas.yok.gov.tr/lisans-anasayfa.php.

[xix] In this classification, dissertations in political science are considered as part of IR. However, some of these theses were merely about domestic politics, actors, or issues, and their subjects cannot even remotely be considered IR. To name a few sample titles: “Aydın siyaset ilişkisi bağlamında Hürriyet Partisi [The Freedom Party in the Context of intellectual-Politics Relationship]”; “Disappearing Onion Producers in Karacabey: A Micro Analysis of Farmers and Land After Structural Reform]; “Türkiye'de sosyalist düşünce ve hareketlerin işçi sınıf ile ilişkisi: 1968-71 fabrika işgal eylemleri [Relationship of Socialist Ideas and Movements with the Working Class in Turkey (1968-71) Factory Occupation Protests]”; “The New Position of Women in Circassian Society Between Circassian Tradition and Dogma Religion,” “Liberal Democratic Party in Turkey’s Aegean Sea Region.” Since some scholars posted only the name of their university of graduation without specifying the department or the topic for their dissertations, we have a limited number of examples. There is enough reason to suspect that if it were possible to have access to more detailed information, the examples would be multiplied.

[xx] Pınar Bilgin and Oktay Tanrısever, “A telling story of IR in the periphery: Telling Turkey About the World, Telling the World About Turkey,” Journal of International Relations and Development 12, no. 2 (2009): 174-179; Mustafa Aydın, Fulya Hisarlıoğlu, and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Alana Yönelik Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir İnceleme:TRIP 2014 Sonuçları,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 3-35.

[xxi] To support this statement, we need a closer look at the doctoral dissertations of the scholars who received their degrees from and also are employed in IR departments. Here are the few sampled titles: “Tanzimat'tan günümüze Türk politik kültüründe romantizm [Romanticism in Turkish political culture since Tanzimat Era]”; “The Role of Turkish Theatre in the Process of Modernization in Turkey: 1839-1946”; “Süleyman Demirel: A Political Biography”; “Aydın siyaset ilişkisi bağlamında Hürriyet Partisi [The Freedom Party in the Context of intellectual-Politics Relationship]”; “II. Meşrutiyet döneminde paramiliter gençlik örgütleri [The Paramilitary Youth Organisations in II.Constitutional Monarchy Period]”; “Siyasal yaşamımız ve Namık Kemal [Our Political Life and Namık Kemal]”; “Türkiye'de bir politik özne olarak gençliğin inşası (1930-1946) [The Construction of Youth as a Political Subject in Turkey (1930-1946)].”

[xxii] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Türkiye Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplininde Özgün Kuram Potansiyeli: Anadolu Ekolünü Oluşturmak Mümkün mü?” Uluslararası İlişkiler 5, no 17, (2008): 178.

[xxiii] There is a growing literature about the intellectual decolonization of IR: Branwen Gruffydd Jones, ed., Decolonizing International Relations (Maryland: Rowman and Littlelfield, 2006); Zeynep Gulsah Capan, “Decolonising International Relations,” The Third World Quarterly 38, no 1 (2017): 1-15.

[xxiv] Furkan Kaya, Mesut Özcan, and Soner Doğan, “Türkiye's Demand for Global Order in The Context of Critical Realizm and ‘The World Is Bigger Than Five Discourse’,” Gaziantep Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 22, no 4 (2022): 2408-2425; Ersoy Önder, “Hangisi Daha Büyük? Dünya mı Beş mi?” Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 12, no 63 (2019): 341-359.

[xxv] Ryoko Nakano, “Beyond Orientalism and ‘Reverse Orientalism’: Through the Looking Glass of Japanese Humanism,” in International Relations and Non-Western Thought. Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity, ed. Robbie Shilliam, (London: Routledge, 2011), 125-138.

[xxvi] Said, Orientalism, 328.

[xxvii] Ersel Aydınlı and Gonca Biltekin, “Widening the World of IR: A Typology of Homegrown Theorizing,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 7, no. 1 (2018): 45-68.

[xxviii] Murat Ercan, Batılı Ülkelerin Dış Politikalarında Türk ve İslam Karşıtlığının Yansımaları [Reflections of Hostility Against the Turks and Islam in the Western Countries’ Foreign Policies] (İstanbul: Efe Akademi Yayınları, 2021).

[xxix] As an example of such works, a brief look at the papers presented at the II. Uluslararası Demokrasi Sempozyumu: Emperyalizm, Hegemonya ve İstihbarat Faaliyetleri, 30 Kasım-2, Aralık 2017 [The Second International Symposium on Democracy Imperialism, Hegemony, and Intelligence Activities, 30 November-2 December 2017] might be helpful.

[xxx] For historical and sociological background, and the current state of conspiratorial thinking in Turkey, look; Doğan Gürpınar, Conspiracy Theories in Turkey. Conspiracy Nation (New York: Routledge, 2020); Julian de Medeiros, Conspiracy Theory in Turkey: Politics and Protest in the Age of 'Post-Truth' (London: I.B. Tauris, 2018).

[xxxi] One of the graduate students in my class, during our discussions of Stanley Hoffmann’s article, IR as an American Science, pointed out that whole IR theory might be a part of an American conspiracy to manipulate minds. Therefore, according to her, it was useless to learn all that literature, which basically is a piece of propaganda.

[xxxii] Most prominent one of these is a well-known geological engineer, Prof. Dr. Şener Üşümezsoy: Üşümezsoy, Dünya Sistemi ve Emperyalizm [The World System and Imperialism] (İstanbul: İleri Yayınları, 2006); Üşümezsoy, Petrol Düzeni ve Körfez Savaşları [The Oil Order and the Gulf Wars] (İstanbul, İnkılap Kitapevi, 2003); Üşümezsoy, Petrol Şoku ve Yeni Orta Doğu Haritası [Oil Shock and the New Map of the Middle East] (İstanbul: İleri Yayınları, 2006); Üşümezsoy, Türkiye’nin Kesik Damarları: Boru Hatları-Kayagazı-Doğal Gaz Savaşı [The Cut Veins of Turkey: Pipelines, Shale Gas, Natural Gas Wars] (İstanbul: İleri Yayınları, 2017).

[xxxiii] Unlike other scholars, who opaquely publish within a conspiracy paradigm and hide their perspectives to avoid blemishing their academic images, Erol Mütercimler openly claims himself to be a conspiracy theorist. For that reason, I saw no harm in naming him as an example. He also published nine issues of a journal titled Komplo Teorileri [Conspiracy Theories]. Erol Mütercimler, Komplo Teorileri: Aynanın Ardında Kalan Gerçekler [Conspiracy Theories: The Realities Behind the Mirror] (Istanbul: Alfa, 2015). Especially in the Introduction part of the book, he explains his mission.

[xxxiv] Here, the number of historians refers to the scholars who had their education in history departments. There is also a part of IR in Turkey called “Political History” and this number excludes such “political historians.”

[xxxv] The term is coined in an international migration context in Ezenwa E. Olumba, “The homeless mind in a mobile world: An autoethnographic approach on cognitive immobility in international migration,” Culture and Psychology 29, no. 4 (2023): 769-790, in order to explain the tension between the past and the present; however, the term is also a good fit for the mindset of chronological historicism and its effects on IR.

[xxxvi] The titles of the doctoral dissertations written by the scholars who are employed in IR departments can give us an idea about both the chronological nature of these studies and how they are unrelated to the IR field: “Türk-Alman askeri ilişkileri (1913-1918) [Turkish-German Military Relations (1913-1918)]”; “Türk-Amerikan Siyasi İlişkileri (1914-1923) [Turkish-American Political Relations (1914-1923)]”; “1908-1923 yılları arası Erzurum vilayeti'nin idari ve sosyo-ekonomik durumu [1908-1923 Administrative and Socio-Economic Situation of the Vilayet of Erzurum]”; “Türk basınında Balkan Savaşları (1912-1913) (İkdam, Sabah, Tanin) [Balkan Wars in the Turkish Press (1912-1913) (İkdam, Sabah, Tanin)]”; “Türkiye-İsveç ilişkileri (1918-1938) [Turkey-Sweden Relations (1918-1938)]”; “Türkiye-İsrail ekonomik ilişkileri (1950-1970) [Turkey-Israel Economic Relations (1950-1970)]” etc.

[xxxvii] Friedrich Meinecke, “Values and Causalities in History,” in The Varieties of History from Voltaire to the Present, ed., Fritz Stern (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 269.

[xxxviii] There are 3 reasons for the engagement between the outer periphery and politics: (1) the outer periphery’s willingness to participate in politics; (2) the quantitative advantage of the outer periphery against the rest of the discipline; and (3) the ideological match between politicians and the outer periphery scholars. In addition, neo-Ottomanism, an anti-elitist ideology that stands against westernization policies of the current government should be mentioned here as part of this ideological overlap. A populist discourse criticizing westernizing elites and tendencies is typical both in government and academic rhetoric in the outer periphery, both feeding into each other.

[xxxix] Stanley Hoffmann, “An American Social Science: International Relations,” Daedalus 106, no. 3 (Summer 1977): 55.

[xl] Geeta Chowdhry, “Edward Said and Contrapuntal Reading: Implications for Critical Interventions in International Relations,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 36, no.1 (2007): 101-111; Pınar Bilgin, “‘Contrapuntal Reading’ as a Method, an Ethos, and a Metaphor for Global IR,” International Studies Review 18, no 1 (2016): 134-146.

[xli] John J. Mearsheimer, “Benign Hegemony,” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 147-149.