Bama Andika Putra,

University of Bristol, UK,

Universitas Hasanuddin, Indonesia

The importance of safeguarding Malaysia’s Kasawari gas field in the South China Sea has reoriented Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies vis-à-vis China’s growing assertiveness in this semi-enclosed sea. China’s increased sea infringements through its coast guards and maritime constabulary forces have led Malaysia to adopt what this article coins as “triadic maritime diplomacy,” a combination of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomacy. Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies thus act more as a set of contradictory policies rather than a decisive attempt to defend Malaysia’s sovereignty at sea. This article engages in qualitative inquiry to address two central empirical questions: Firstly, how has Malaysia managed the delicate balance between safeguarding its sovereignty at sea and maintaining close economic ties with China? Secondly, what accounts for Malaysia’s persistent “downplaying” stance despite the escalating intrusions around the Luconia Shoals, particularly concerning the Kasawari gas field? The findings of this study reveal three key aspects: Firstly, Malaysia’s prioritization of developing the Kasawari gas field has necessitated the adoption of seemingly contradictory policies, employing coercive maritime measures utilizing its naval assets while simultaneously adopting rhetoric that downplays crises. Secondly, Malaysia’s maritime diplomacy can be aptly characterized as “triadic” strategies, encompassing the adoption of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative approaches. Lastly, these seemingly inconsistent policies are a strategic response aimed at accommodating both immediate and prospective economic opportunities involving China, all while signaling its nonaligned stance to major global powers.

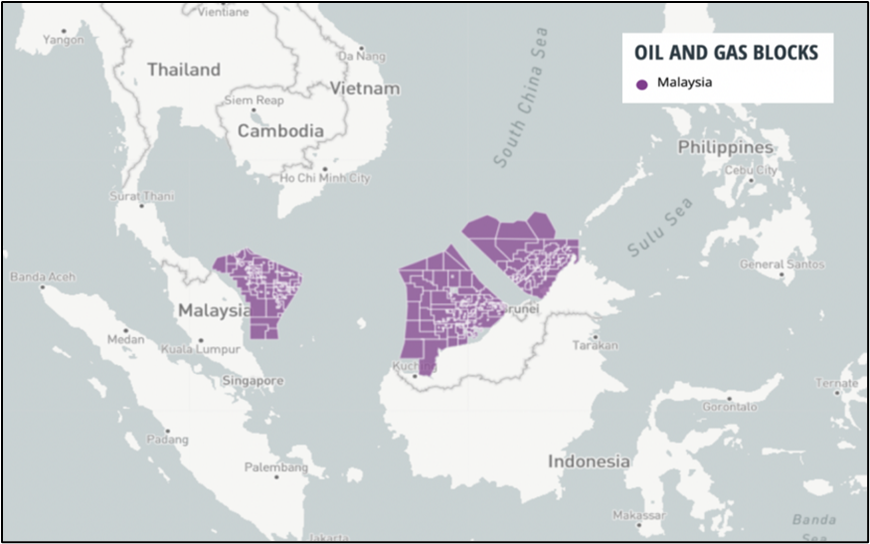

The South China Sea disputes remain a flash point with the possibility of escalating into bloody armed conflict, a dire situation that could undermine not only regional security and stability but also the national security interests of claimant states. Malaysia’s sovereign rights and territorial claims in this semi-enclosed sea have become increasingly threatened in recent years. Such threats predominantly stem from the persistent and increasing encroachment and harassment of Chinese maritime constabulary forces in the vicinity of the disputed maritime features, i.e., submerged reefs, atolls, and shoals within Malaysia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).[i] Malaysia’s concerns and apprehension regarding China’s growing assertive actions in these offshore contested waters are warranted, particularly within the latter’s declared U-shaped nine-dash line. These vast and yet remote maritime areas are home to abundant untapped oil and gas reserves with the potential to support Malaysia’s economic growth for decades[ii] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Malaysia’s Hydrocarbon Energy Exploration and Development in the South China Sea

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative[iii]

Over the past 20 years, China has consistently exhibited belligerent behaviour in defending its South China Sea claims. Clear evidence of this behaviour can be seen in its unilateral large-scale land reclamation activities, including transforming previously submerged reefs, atolls, and shoals in the Spratly Islands into fortified artificial island outposts.[iv] Beijing’s strategy for boosting China’s territorial claims also involves militarizing these reclaimed maritime features. This includes the establishment of military garrisons, the installation of missile defence and advanced radar systems, as well as the construction of extended airstrips and sheltered ports.[v] Initially, most of these assertive actions, as reported in mainstream media, focused on the EEZ waters claimed by the Philippines and Vietnam For the Philippines, decades-long intrusions and confrontations with the Chinese Coast Guard have escalated with the use of military-grade lasers in the past year.[vi] Meanwhile, Vietnam is struggling to respond to China’s continuous assertiveness at sea, which has escalated since the May 2014 drilling rig crisis, which occurred close to the Paracel Islands.[vii]

Nevertheless, China’s belligerent behaviours have visibly expanded to other contested areas within its nine-dash line, including a vast tract of Malaysia’s claimed EEZ.[viii] This development has gained traction in the last decade, as demonstrated by recurrent intrusions of Chinese maritime militia and Coast Guard vessels in the vicinity of Malaysia’s claimed James Shoal and Luconia Shoals off the Sarawak coast of Borneo.[ix] China regards James Shoal as its southernmost territory, prompting Beijing to project its maritime power just off the coast of Sarawak. Consequently, China has been persistent in its claims on the Luconia Shoals, seizing the shoal in 2013 and anchoring its ships consistently between 2013 and 2015.[x] Furthermore, tensions heightened in 2014 when Chinese officials decided to conduct a sovereignty oath-swearing ceremony with the presence of its three warships in Malaysia’s James Shoal.[xi]

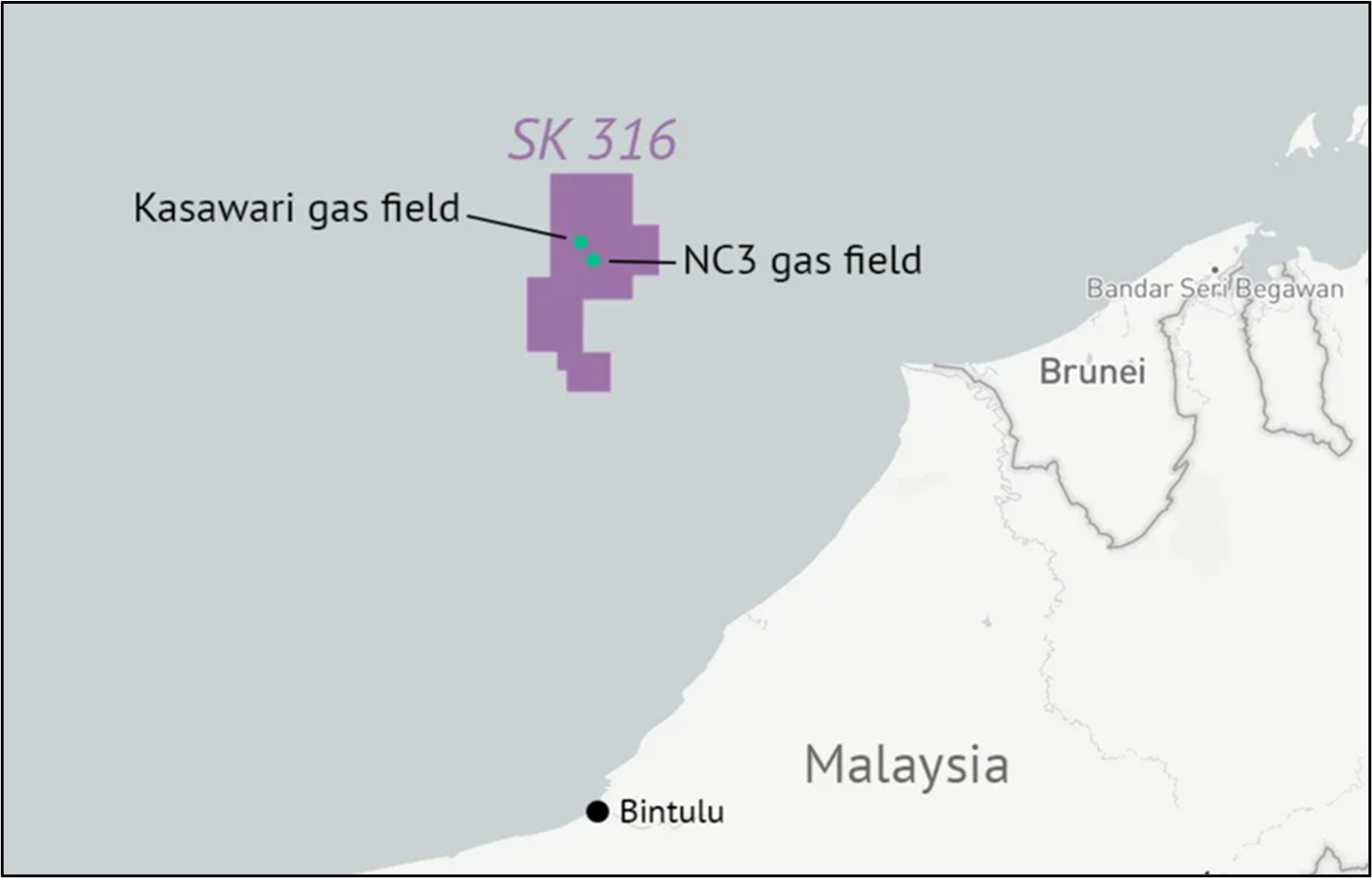

A particular maritime area in the South China Sea that has recently seen a troubling surge of China’s aggressive activities and posed an alarming concern for Malaysia is the Kasawari Gas Development Project (see Figure 2). This remote offshore gas field, situated adjacent to the disputed Luconia Shoals,[xii] was discovered in November 2011 by PETRONAS and has currently undergone extensive development.[xiii]

Figure 2. Location of the Kasawari and NC3 Gas Fields

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative[xiv]

In response to these activities, Beijing began to resort to direct and sizable use of non-military force by dispatching its Chinese Coast Guard (CCG), civilian, and maritime militia vessels to operate in the vicinity of the contested area and to deliberately harass Malaysian gas drilling operations.[xv] The regular presence and harassment by these non-military assets indicate Malaysia is now non-immune from the brunt of Beijing’s grey zone tactics,[xvi] which had been widely observed in the waters around the disputed maritime features in the EEZ of the Philippines and Vietnam. Beijing’s preference for conducting grey zone operations in the vicinity of the Kasawari gas field demonstrates the adoption of a new doctrine of maritime coercion characterized by ambiguity and deception while avoiding the risk and cost of full-blown military conflict when pursuing the objectives.[xvii] This tactic shows China’s willingness to engage in aggression against Malaysia, even if such actions may lead to diplomatic frictions and territorial standoffs.

Evidence of China’s grey zone tactics is fully displayed in the disputed waters, including the deployment of the CCG and Chinese-flagged government vessels and their engagement in dangerous navigational maneuvers. In employing its grey zone tactics, Beijing takes a number of approaches. It relies on a certain escalation of tensions at sea and resorts to military tactics aimed at compelling adversaries in the maritime domain.[xviii] Unauthorized marine scientific surveys were also visibly conducted by the Chinese-registered research vessels in the area. This was encountered by Vietnam in the Vanguard Bank in late 2019, in which the Haiyang Dizhi 8, a Chinese Geological Survey Ship, was accompanied by a number of CCG vessels to conduct seismic surveying.[xix] The following year, China’s grey zone tactics also led to a standoff between Malaysian and Chinese officials due to a confrontation faced by a PETRONAS-contacted exploration vessel, the West Capella.[xx] Overall, the underlying objectives behind China’s grey zone tactics are intended to disrupt Malaysia’s Gas Development Project around the Kasawari gas field[xxi] and deny the country’s entitlement to continue exploring hydrocarbon resources in the area.[xxii]

One can argue that these two-pronged strategies are intended to deny Malaysia its rights to access and develop hydrocarbon resources and safeguard China’s claims and interests within the nine-dash line. Beijing steadfastly declared that these offshore areas historically belong to the country and constitute an integral component of the country’s “indisputable sovereignty.”[xxiii]

In addition to the at-sea confrontations, China’s utilization of the grey zone tactics extended to activities beyond the sea, including encounters with the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF). Tensions above the Malaysian airspace of the Luconia Shoals area escalated in 2021 when RMAF detected and intercepted 16 Chinese military aircraft flying in a tactical formation near the disputed waters of the shoals.[xxiv] This instance alone does not match Malaysia's assertiveness in the maritime domain. After the crisis, Chinese officials clarified that it only maintained the rights of overflight within its airspace.[xxv] However, Malaysia’s responses were justified, as the accumulation of assertiveness it faced in both the maritime and airspace domains led to a conclusion of China’s growing assertiveness vis-à-vis China’s claims in the South China Sea.

In the face of escalating Chinese aggression and harassment in Malaysia’s Kasawari gas field, it is perplexing that the Malaysian government appears to downplay its response to Beijing’s maritime power projections at sea. Instead of deploying its naval warships, Malaysia has preferred using its coast guard, the Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA), to respond to the aggressions committed by Chinese civilian maritime vessels. As with any other Southeast Asian claimant state, the rationale behind Malaysia’s choice to rely on maritime constabulary forces when dealing with CCG intrusions is rooted in strategic considerations.[xxvi] Maritime constabulary forces are civilian fleets, and thus, the likelihood of escalation to a full-blown crisis from their deployment is arguably lower than the use of military forces.[xxvii]

Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies are arguably a contradictory policy rather than displaying a firm commitment to assert and defend its sovereignty in the maritime domain at any cost. Despite China’s increased sea intrusions through its coast guards and maritime constabulary forces, Malaysia has adopted what this article terms “triadic maritime diplomacy,” involving a combination of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime strategies. This qualitative inquiry addresses two central empirical questions: How has Malaysia managed the delicate balance between safeguarding its sovereignty at sea and maintaining close economic ties with China? Second, what explains Malaysia’s persistent “downplaying” stance despite the escalating intrusions around the Luconia Shoals, particularly concerning the Kasawari gas field?

In answering both those inquiries, this research adopts qualitative research utilizing primary data obtained from government reports, documents, and official speeches issued by relevant Malaysian ministries and bodies between 2011 and 2023. In an attempt to triangulate the findings, this study further utilizes secondary data from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), media publications, and research reports related to Malaysia’s policies vis-à-vis the South China Sea between 2011 and 2023. This article specifically utilizes data from AMTI as the initiative’s access to automatic identification systems (AIS) allows this study to capture instances of Chinese intrusions into Malaysia’s waters, including the responses made by Malaysia vis-à-vis those acts of belligerence. This research is an interpretive attempt to better decipher Malaysia’s South China Sea strategies against China’s growing aggressions in its EEZ areas, with its analytical framework informed by Le Mière’s conception of maritime diplomacy. According to Le Mière, policymakers and academics can better understand the maritime diplomatic intentions of states by categorizing their policies into three parts: coercive, co-operative, and persuasive maritime diplomacy. Through this categorization, this study can provide an alternative interpretation of contemporary Malaysian diplomatic actions in the maritime domain.

Extensive literature exists on understanding Malaysia’s South China Sea policy and strategy. An opinion that unites the different traits in comprehending Malaysia’s responses to the disputes within its sovereign waters is that Malaysia is, without a doubt, attempting to secure its rightful resources within its borders. Nevertheless, the distinction among studies relates to what driving factors influence Malaysia’s South China Sea policies and how Malaysia has responded to the emerging crisis.

Part of the literature discusses systemic and domestic factors influencing Malaysia’s foreign policy decisions in the South China Sea. Lai and Kuik, for example, contend that Malaysia’s hedging policies, which show a certain level of defiance and open accommodation, could be understood by structural factors underpinning their decision.[xxviii] Similar to the conclusions reached by Lai and Kuik, Noor and Qistina further inquired into the role of structural factors and found that Malaysia’s traditional independent stance in response to the great power rivalries in the Asia-Pacific is a primary contributor to Malaysia’s mixed engagement with the U.S. and China.[xxix] Contrary to most studies evaluating structural factors, Ngeow argues that Malaysia’s South China Sea policy could be better comprehended by understanding the domestic policy decision-making process and examining the dynamics at play.[xxx]

An equally important inquiry into Malaysia’s South China Sea policies is how Malaysia responds to any crises within its maritime domain. Generally, there is a consensus that Malaysia adopts a conservative stance in its sea confrontations.[xxxi] However, some have argued that Malaysia has gradually signaled assertiveness toward China’s aggressions.[xxxii] Noor concluded that the Malaysian government is beginning to respond strongly to China’s claims within Malaysia’s EEZ, primarily due to the untapped energy resources falling under Malaysia’s maritime jurisdictions.[xxxiii] Despite the tensions Malaysian policymakers face vis-à-vis China’s uncertain rise in the region, studies have not been able to conclude that Malaysia perceives China as a source of threat. Syailendra’s recent article argues that Malaysia does not adopt a threat perception towards itself, with the intention of deterring possibilities of a crisis.[xxxiv] In making sense of this, consultation with Milner’s studies on Malaysian foreign policy indicates that Malaysian foreign policymakers perceive the world from a non-Western international relations perspective, which leads it to not take decisive action in the face of what may be a clear threat for Western policymakers.[xxxv]

Existing studies suggest Malaysia takes its South China Sea claims seriously. Despite taking a relatively reserved approach compared to other claimant states, such as the Philippines and Vietnam, Malaysia is wary about the untapped gas resources below the disputed waters. Nevertheless, three significant gaps exist in the discourse of Malaysia’s policies in the South China Sea. Firstly, there is currently no study that evaluates Malaysia’s diplomatic strategies vis-à-vis the growing assertive maneuvers of China in the overlapping EEZ between Malaysia and China, particularly in the Kasawari gas field. Secondly, existing studies have overlooked the possible nexus between the vast gas reserves that Malaysia could exploit and the changes in its approach to maritime diplomatic strategies. Thirdly, there is a lack of empirical studies that examine how tensions in grey jurisdictional zones are addressed through maritime diplomatic strategies.

This article argues that the deficiencies in the existing literature can be covered by an inquiry into Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies in the South China Sea disputes. By adopting Le Mière’s conception of maritime diplomacy, this article will classify maritime diplomatic actions into coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomacy. Through this classification, we can better understand Malaysia’s implemented maritime diplomatic strategies and why the country adopts contradictory policies to manage tensions arising from the South China Sea crisis, particularly in response to China’s aggressive behaviour in the Kasawari gas field. In simple terms, maritime diplomacy involves managing international relations through the maritime domain.[xxxvi]

Traditionally, the dominant discourse of maritime diplomacy focused on the use of hard power assets, primary state navies, to compel and deter adversaries.[xxxvii] While the literature has evolved to include maritime constabulary forces such as coast guards and maritime security agencies, navies remain paramount stakeholders when compared to other maritime agencies. As argued by past scholars such as Mahan and Cable, navies have the capacity to conduct gunboat diplomacy,[xxxviii] enabling them to exert influence and uphold a state’s sovereignty at sea.

Navies indeed have well-defined diplomatic roles that can help their own state achieve various goals. Luttwak, for example, argues that navies could serve crucial maritime diplomatic functions, particularly for executing operations related to political goals.[xxxix] The idea forms the basis of Le Mière’s approach in 2014, conceptualizing maritime diplomacy into three distinct categories: coercive, persuasive, and co-operative.[xl] The discussions of employing hard power assets for diplomatic purposes fall under Le Mière’s categorization of “coercive maritime diplomacy.” He argues that states choose different maritime diplomatic strategies based on their specific diplomatic objectives.[xli]

In the following sections, this article argues that Malaysia employs a combination of Le Mière’s maritime diplomacy categories. In the context of Malaysia’s claims in the South China Sea, this blend of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomacy is termed “triadic maritime diplomacy” in this article. This study is the first to propose the existence of this trilateral form of maritime diplomacy, and it will provide explanations for why states employ diplomatic strategies and, hence, their adoption of contradictory policies. Moreover, this article explores how these diplomatic approaches are implemented in grey-zone jurisdictional areas, such as the waters surrounding the Luconia Shoals.

The focal point of contention between Malaysia and China in the South China Sea in recent years undeniably revolves around Malaysia’s controlled Kasawari gas field near the Luconia Shoals. It was not until 2014 that diplomatic tensions and at-sea standoffs between the two countries escalated significantly in that area. This coincides with the intensification of PETRONAS-operated exploration and drilling activities for natural gas.[xlii] For Malaysia and China, the South China Sea consists of abundant natural gas reserves, which are critical in a time of energy scarcity. AMTI estimates that the South China Sea consists of 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 10-11 billion gas reserves.[xliii] Consequently, for Malaysia, as reported by the Malaysian Foreign Minister in 2021, the three trillion cubic feet of natural gas are within Malaysia’s sea borders and have resulted in exploration by Malaysia’s state-owned company, PETRONAS, since 2011.[xliv]

As claimed by PETRONAS, the Kasawari Gas Development Project is one of the world’s largest offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects.[xlv] Through the exploration of the wells of Kasawari-1 and NC8SW-1, PETRONAS discovered gas reserves offshore of Sarawak in 2011.[xlvi] The following year, PETRONAS was determined to further the exploration by drilling an additional 30 exploration wells, with prospects of finding oil and gas reserves that the Malaysian people well needed.[xlvii] A decade later, the Kasawari gas field has secured the interest of Malaysian policymakers, as it is currently in the construction stage. In January 2020, PETRONAS conducted its first steel cut ceremony, marking the start of its construction.[xlviii] It is expected to start commercially producing in 2023, reaching its peak production in 2026, which is forecasted to continue until the fields reach their economic limit in 2052.[xlix]

The development of Malaysia’s Kasawari gas field fulfills a domestic demand for gas and oil scarcity. As seen in the past two years and reported by the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, fuel prices have not been manageable domestically due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.[l] With Malaysia’s economy continually rising each year, demand for energy will rise, and the Kasawari gas field will help alleviate the energy crisis. However, this does go against Malaysia’s intentions to transition to cleaner energy. As Malaysia’s Ministry of Economy has stated, “Malaysia is committed to low carbon development aimed at restructuring the economic landscape to a more sustainable one.”[li] This is expected through an energy transition to renewable energy, bioenergy, hydrogen, and other forms supporting Malaysia’s energy transition intentions. Nevertheless, Malaysia is seen to defend the current construction taking place in the Luconia Shoals, indicating the importance of conventional energy sources.

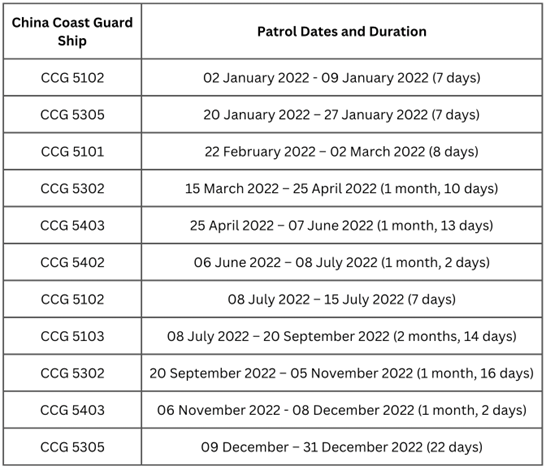

As mentioned earlier, the intensification of oil and gas explorations within Malaysia’s Kasawari gas field has triggered aggressive responses from China. Beijing perceives this gas field as an integral part of its southernmost territory within the nine-dash line.[lii] Hence, it was inevitable that the rapid development of this gas field prompted Beijing to dispatch its coast guard and maritime militia vessels to the vicinity to harass and interrupt the operations there. Table 1 shows the activities and years of incidents related to China’s assertive actions around the vicinity of the Kasawari gas field, which comprises the China Coast Guard patrols around the Luconia Shoals.

Table 1: China Coast Guard Patrols in the Luconia Shoals, the South China Sea (2022)

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative 2022[liii]

An alarming trend that demands attention by the Malaysian authorities pertains to China’s increased adoption of a grey zone strategy, including the deployment of maritime constabulary forces encroaching into Malaysia’s EEZ areas in the South China Sea. The Malaysian authorities reported 89 instances of Chinese intrusions into Malaysian waters between 2016 and 2019, all of which involved naval and coast guard vessels.[liv] These strategic moves have raised concerns among Malaysian officials, as these Chinese vessels would prolong their operation within Malaysia’s EEZ waters until Malaysian navy vessels arrived at the scene.[lv] It is imperative to recognize that China’s assertive actions should not be regarded as an isolated incident. Numerous Southeast Asian countries, whether claimants or not, have encountered a similar surge of incidents involving Chinese naval and coast guard vessels operating in the disputed waters without authorization.[lvi] As China intensified its assertive activities involving large-scale land reclamation and militarization on its occupied maritime features in the South China Sea, instances of Chinese vessels establishing a presence using both civilian and military maritime constabulary forces witnessed a notable increase, particularly within its declared nine-dash line.[lvii]

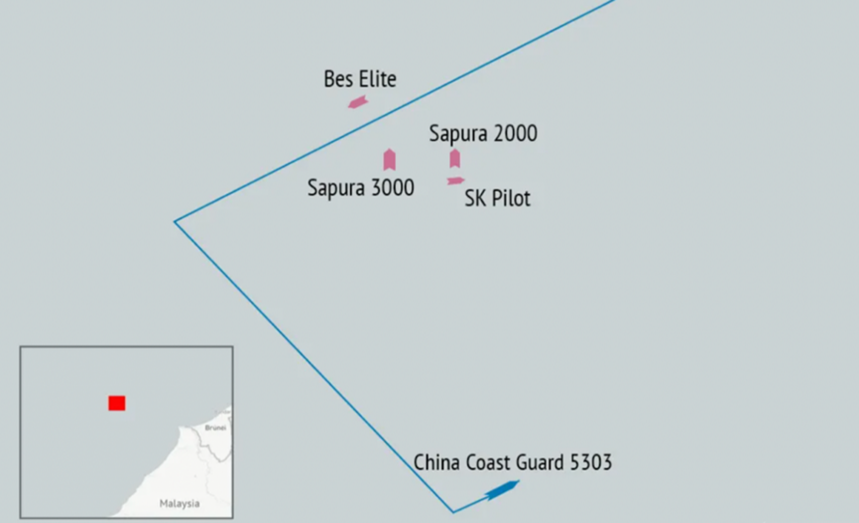

Since the beginning of Malaysia’s Kasawari gas exploration and development, CCG and maritime militia vessels were ordered by Beijing to navigate around Malaysia’s gas exploration and drilling site, deliberately choosing sea routes to emphasize China’s active presence and provoke Malaysian officials.[lviii] As shown in Figure 3 below, in July 2021, CCG vessel 5403 traveled in close proximity to Malaysia’s Sapura 2000 and Sapura 3000 dredgers in the Kasawari gas field. An interesting observation during this crisis was the presence of Malaysia’s navy vessel, Bunga Mas Lima, near these maneuvers.

Figure 3. CCG 5303 Maneuvers July 5, 2021

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative[lix]

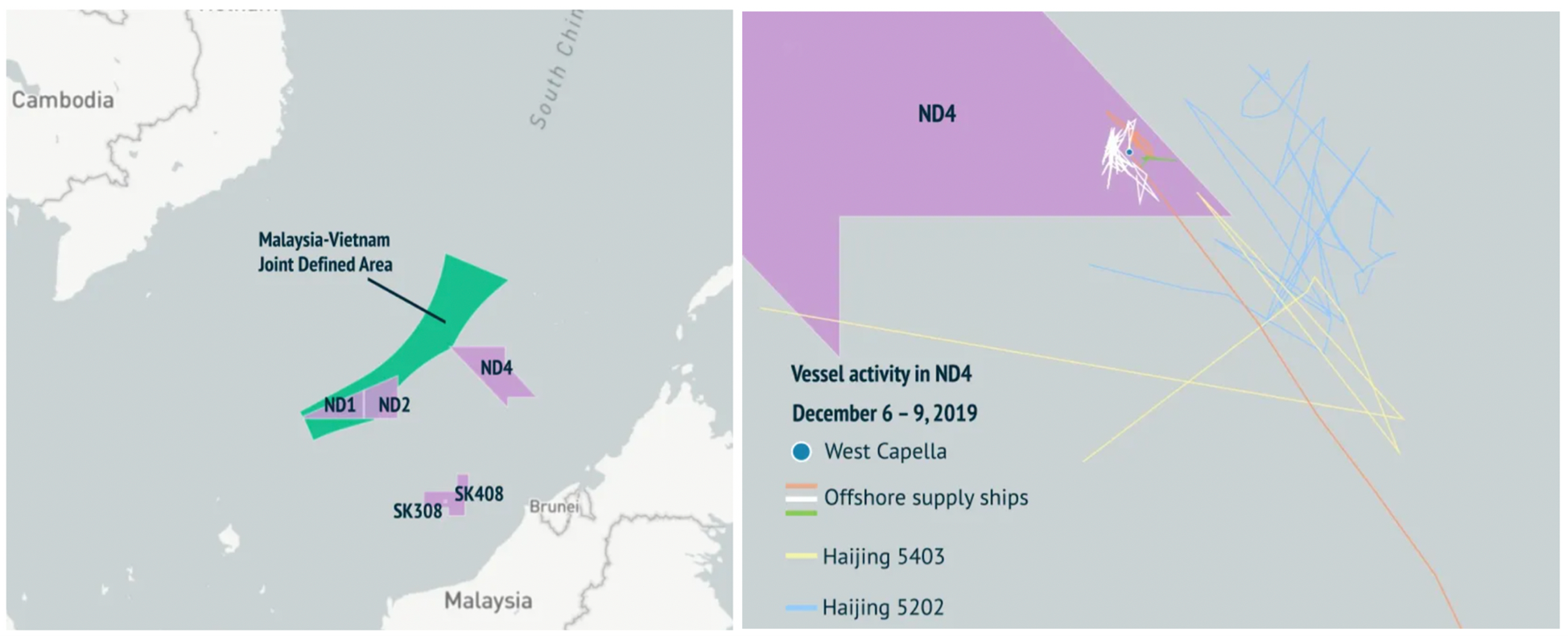

It is noteworthy that both Malaysia and China have occasionally found themselves in maritime standoffs, albeit short of direct military skirmishes. These at-sea confrontations have frequently involved the CCG and the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) as both parties vie to exercise control over the disputed areas. Take, for example, a year prior to the crisis involving the Sapura 2000 and Sapura 3000 Malaysian dredgers, which was the standoff between Malaysian and Chinese vessels involving the West Capella, a drillship contracted by PETRONAS. The West Capella, having operated in the ND4 (see Figure 4), faced high-risk intimidation due to the near-constant presence of the CCG 5203 and 5305, which aimed to disrupt the oil and gas operations in the Luconia Shoals.[lx] Consequently, similar to Malaysia’s past stance in responding to crises at sea, Malaysian officials deployed the KD Jebat to guard the West Capella and other supply ships at sea.

Figure 4. Tensions involving the West Capella in 2020

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative[lxi]

More recently, AIS data in 2023 revealed that China assigned its CCG 5901 vessel to operate closer to Kasawari, starting from a distance of 7 nautical miles in the second week of February and decreasing to 1.5 nautical miles the following week.[lxii] (AMTI 2023c). Because CCG 5901 had been operating in the vicinity of Malaysia’s Kasawari Gas Development Project for an extended period, the RMN once again had to intervene until the CCG abandoned its position.[lxiii]

Malaysia’s responses have been consistent in the face of the crisis caused by China’s assertive maneuvers at sea. Through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), the Malaysian government publicly and consistently emphasizes its commitment to defending the nation’s sovereignty in the South China Sea, even amidst the evolving tensions with China.[lxiv] The defence of the country’s sovereign rights in these disputed waters has been entrusted to its primary forces, which include the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF), the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN), and the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA). Collectively, these entities play a pivotal role in the conduct of surveillance and patrols within Malaysia’s vast EEZ areas. This includes tailing and responding to CCG patrols that have oftentimes included the deliberate positioning of vessels within Malaysia’s sovereign borders.

Although both Chinese coast guards and maritime militia vessels, in addition to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy, have increasingly encroached upon Malaysia’s EEZ in recent years, the Malaysian government is more inclined to mitigate any arising tensions, restraining itself from openly condemning China’s actions. As observed by Storey, Malaysia’s deliberate diplomatic approach was particularly evident during Najib Razak’s tenure from 2009 to 2018, when Malaysia’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) led to the tendency to downplay Chinese intrusions into Malaysian waters.[lxv] During this time, Malaysia also adopted the position that intrusions by CCG vessels were not a serious concern as long as they did not involve the PLA Navy.[lxvi]

Nevertheless, the prevailing perception of Malaysia’s seemingly measured and subdued position in response to China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea disputes can be challenged. A notable transformation in Malaysia’s foreign policy orientation has taken shape in recent years, driven by the substantial socio-economic significance of the Kasawari Gas Development Project to Malaysia and the escalating aggression of China in the vicinity. Recent tensions in these areas have intensified Malaysia’s dilemma in the South China Sea.

Traditionally, the country has been willing to defend its sovereignty at sea but has refrained from taking decisive action due to the importance of China as Malaysia’s leading trading partner.[lxvii] Malaysia’s active development over Kasawari and its determination to safeguard development projects through its naval forces present an empirical puzzle. As Malaysia naturally downplays the South China Sea issue and avoids coercive measures to defend its claims, the significance of gas explorations for the country’s socio-economic growth has shifted its South China Sea stance.

A surprising development transpired during Anwar Ibrahim’s first official visit to China in March 2023. Notwithstanding the strong economic relations between Malaysia and China, Chinese officials expressed their concerns about PETRONAS’ gas development operations within China’s alleged nine-dash line.[lxviii] Anwar Ibrahim had to reassure China that the operations were conducted well within Malaysia’s EEZ[lxix] but still expressed a willingness to negotiate with China.[lxx] From the outset, Malaysia’s current position is that while it is willing to downplay its claims in the South China Sea, the country is unwilling to downplay the importance of the Kasawari gas field for Malaysia. The oil and gas industry contributes significantly, accounting for 20% of Malaysia’s GDP.[lxxi]

The following section will further attempt to expound on this emerging empirical puzzle in Malaysia’s contemporary South China Sea claims and postures. It employs Le Mière’s conception of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomacy and the emergence of paragunboat diplomacy to better understand Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies. As stated earlier, this strategy is termed “triadic maritime diplomacy.”

Malaysia’s distinctive approach to maritime diplomacy engagements in addressing China’s growing assertiveness within its maritime jurisdictional waters, the South China Sea, is termed in this article as “triadic maritime diplomacy.” Le Mière argued that maritime diplomacy is defined simply as the utilization of the maritime domain to manage international relations, which can take the three following distinct forms: coercive maritime diplomacy entails the use of force or threat to compel adversaries; persuasive maritime diplomacy includes an act of “showing the flag,” an attempt to showcase a state’s maritime power and capability;[lxxii] and lastly, co-operative maritime diplomacy employs maritime assets as a form of soft power to manage international relations peacefully. This article argues that Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategy combines elements of coercion, persuasion, and cooperation.

Within Malaysia’s maritime diplomacy framework, the paramount emphasis is directed to the multiple facets of maritime affairs, intertwining elements of commerce and the military within Malaysia’s territorial waters.[lxxiii] Particularly relevant to the South China Sea disputes is the expanding spectre of state-driven threats embraced by the claimants and non-claimants, exerting influence that could destabilize Malaysia’s maritime initiatives and practices of security at sea. In operationalizing this maritime security framework, the main entity responsible is the RMN, one of the military branches tasked to safeguard Malaysia’s sovereignty in the South China Sea. Meanwhile, since 2004, the MMEA has been legislatively designated as the principal federal agency responsible for ensuring the safety and security of the country’s maritime jurisdictional zones.[lxxiv]

Consequently, delving into the nuances of Malaysia’s international interactions in the context of the maritime domain necessitates a rigorous examination of the actions and policies practiced by the RMN and MMEA. Both of these law enforcement organizations, in conjunction with state-owned vessels, collectively play a pivotal role in ensuring the uninterrupted progress of the Kasawari gas development initiatives. The deployment and operation of state navies, recognized as an essential component of a state’s diplomatic arsenal in maritime affairs, constitute fundamental aspects of Malaysia’s maritime diplomacy. Moreover, it is worthwhile to recognize the importance of the paramilitary functions of MMEA, with its civilian orientation and its primary focus as a maritime constabulary force in this semi-enclosed sea.

The Malaysian navy has consistently played a paramount role in Malaysia’s responses to Chinese intrusions. Previous literature has referred to the use of navies to coerce and compel adversaries as “gunboat diplomacy,” which is now more commonly termed “coercive diplomacy” to encompass non-state actors within the scope of analysis.[lxxv] Malaysia’s coercive diplomacy is predominantly driven by political objectives. Instead of manifesting into actual statements, this diplomacy is generally assessed through actions at sea. As evidenced by the cases observed in Figures 2, 3, and 4, Malaysian naval forces have emerged as the primary tool for showcasing Malaysia’s unwavering commitment to the non-negotiable sovereignty of its territory.[lxxvi] Moreover, the navy serves as a means to compel CCG vessels to vacate the surrounding waters of both the Luconia Shoals and the Kasawari Gas Development Project. Le Mière argues that maritime diplomacy aims to convey messages and signals to opponents. The Malaysian navy has been deliberately deployed to convey signals of the country’s discontent with China’s assertive actions. Scholarly works suggest that both gunboat diplomacy and coercive maritime diplomacy serve as foreign policy doctrines, deliberately employing assertiveness at sea as a constructed strategy with specific political goals.[lxxvii] As demonstrated in a naval exercise in 2021,[lxxviii] Malaysia signaled its assertive intent in the South China Sea by conducting a naval drill to showcase its capabilities, particularly in response to escalating tensions within Malaysia’s EEZ.[lxxix] The utilization of Malaysian naval forces in response to incidents involving CCG intrusions may seem coincidental at first glance. It is essential, however, to avoid prematurely concluding that Malaysia is pursuing a coercive shift in its South China Sea strategies. Determining the coerciveness of maritime diplomatic strategies is inherently linked to the geographical context in which they unfold.

These dynamics suggest that the use of Malaysian naval forces may not necessarily imply a deliberate strategy of coercive maritime diplomacy. Instead, it could be a result of the close proximity of the locations of James Shoal and the Luconia Shoals to the mainland of Sarawak, necessitating the operation of naval vessels by Malaysian authorities.[lxxx] In addition, the patrolling and surveillance capabilities of the MMEA are still limited, possibly due to its lack of facilities, human resources, and assets.[lxxxi] In essence, while it is evident that Malaysia employs elements of coercive maritime diplomacy, deciphering the precise nature of its political intentions is a complex challenge.

Other Southeast Asian countries tend to deploy their maritime constabulary forces rather than navies in response to CCG intrusions and harassment in their territorial waters. Notable instances of this approach can be observed in the context of Indonesia, which typically relies on the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency (BAKAMLA),[lxxxii] and Vietnam, which conducts its maritime power projections through its Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance (VFRS) fleets.[lxxxiii] In contrast, the Philippines has a distinct pattern of employing its coast guard to achieve maritime diplomatic objectives, as its leadership refrains from adopting a coercive maritime diplomatic strategy in order to secure economic benefits from submitting to China’s lucrative economic opportunities.[lxxxiv]

Malaysia’s persuasive maritime diplomatic efforts in the South China Sea complement its triadic maritime diplomacy. Unlike coercive diplomacy, persuasive diplomacy’s primary aim is to demonstrate the presence and effectiveness of its maritime capabilities—a form of the “showing the flag” policy.[lxxxv] Consequently, its implementation does not intend to coerce or deter adversaries. The jurisdictional areas where Malaysia’s navy operates cover all of Malaysia’s maritime zones, including the territorial sea, EEZ, and the continental shelf.[lxxxvi] Therefore, given that most of the tensions that ensued from the CCG intrusions have occurred in the Luconia Shoals, which is within 100 nautical miles of Malaysia’s baseline, it is expected that Malaysia’s navy will operate and assert its presence in those surrounding waters.

Great powers frequently employ persuasive diplomacy to assert their ongoing maritime dominance.[lxxxvii] However, for secondary states such as Malaysia, the strong presence of naval forces in Malaysia’s EEZ waters poses a challenge when considering it as a mere display of maritime capabilities. This challenge becomes particularly apparent in the context of Malaysia’s stance towards the South China Sea, where it has embraced the tendency to downplay many past crises and shunned interpretations of CCG intrusions as threats.[lxxxviii] Nevertheless, as persuasive maritime diplomacy does not require explicit deterring and compelling intentions, Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategy incorporates elements of persuasive maritime diplomacy, albeit with unique considerations in the context of the South China Sea.

In an effort to balance the perceived assertive gestures at sea, Malaysia also employs co-operative maritime diplomacy. Events falling under this category involve states sharing political goals to achieve common goals.[lxxxix] Co-operative diplomacy harnesses soft power by utilizing hard power assets such as navies or maritime constabulary forces, taking the form of goodwill visits, humanitarian assistance, training and joint exercises, and joint maritime security operations.[xc] In the case of Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategy, a key element has been the cultivation of influence and coalitions through joint navy exercises and drills, a role primarily managed by the RMN and supported by the MMEA.

In 2017 and 2021, Malaysia held the Malaysia-Thailand-Indonesia (MTA) joint naval exercise with the U.S., aiming to foster a conducive maritime diplomatic environment in the Indo-Pacific region.[xci] Malaysia’s navy also collaborated with the U.S. in the ASEAN-U.S. Maritime Exercise in 2019, which consisted of maritime drills in the South China Sea flashpoints.[xcii] Additionally, Malaysia sought partnerships with neighboring nations, including Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore, conducting joint naval exercises on three occasions in 2022.[xciii] Through these joint exercises, Malaysia’s co-operative maritime diplomacy signifies its willingness to cooperate with other stakeholders in managing international relations at sea. However, the ongoing regional engagement that the Malaysian navy maintains with its Southeast Asian counterparts and with the U.S. underscores Malaysia’s strong preferences for co-operative maritime diplomatic strategies in addressing tensions in the South China Sea.

Nonetheless, the MMEA has also actively engaged in co-operative maritime diplomatic activities. In 2013, the Japan Coast Guard conducted maritime security drills in collaboration with the MMEA. The joint drills held significant importance for Malaysia’s coast guard, as it marked their first time training with long-range acoustic devices as part of a drill scenario designed to respond to intrusion in the South China Sea.[xciv] The MMEA serves as Malaysia’s principal maritime law enforcer.[xcv] However, it faces significant resource constraints,[xcvi] particularly when compared to the fleets of CCG. Consequently, Malaysia’s navy has assumed the frontline responsibility for asserting sovereign dominance. These resource shortages are surprising, considering that the MMEA’s vision is “to be among the best maritime law enforcement agencies in the world.”[xcvii]

There are high expectations that the MMEA will step up its role in Malaysia’s maritime diplomacy. As seen in the case of Indonesia, maritime security agencies are taking on more active roles in both coercive and co-operative maritime diplomacy. Indonesia’s BAKAMLA, for instance, serves as Indonesia’s primary agency with the assigned role of deterring CCG intrusions, offering a less escalatory alternative to using naval forces.[xcviii] The MMEA can contribute strategically to Malaysia’s overall maritime diplomatic strategy. Maritime constabulary forces possess greater flexibility and, being civilian and non-military in nature, can undertake limited coercive actions to deter and compel adversaries at sea.[xcix] Unlike navies, whose operations can easily be perceived as escalating conflicts, maritime security agencies are often considered acceptable actors for peacefully managing tensions.

Recent developments in Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies reflect a preference for a triadic approach to counter China’s assertiveness at sea, particularly in the vicinity of the Kasawari gas field and the Luconia Shoals. Malaysia’s traditional stance in the South China Sea involves balancing domestic demand to protect its sovereign waters while maintaining a measured response to crises due to the importance of China in Malaysia’s development. The seemingly contradictory stance is achieved by employing a combination of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomacy to yield maximal benefits.

Malaysia’s approach to South China Sea-related crises differs from that of its ASEAN counterparts. There has been a clear pattern since 2015 showing that Southeast Asian states have increasingly invested in and emphasized the role of maritime constabulary forces and coast guards in defending their sovereignty at sea.[c] All claimant states of the South China Sea disputes have expressed their unwavering commitment to defending their respective claims in the disputed waters. The Philippines has taken a distinctly legal stance to its claims.[ci] Meanwhile, Vietnam has adopted a strategy similar to China’s, utilizing maritime constabulary forces to assert effective control at sea.[cii] In contrast, Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies aim to demonstrate moderate decisiveness while retaining the flexibility to negotiate terms for a peaceful resolution. Nevertheless, it has been pivotal for Malaysia to stay consistent towards its issued Defence White Paper 2019, categorizing the uncertainties of the great power rivalry of the U.S. and China in the region and the intrusions into Malaysia’s territory in the South China Sea as a major concern for the administration.[ciii]

To understand the trends displayed by Malaysian policymakers, we first examine China’s economic significance as Malaysia’s leading trading partner. In this context, it is important to consider Malaysia’s deep economic connections with the world’s most robust economy. Statistics reveal China has remained Malaysia’s major trading partner for 14 consecutive years, with the two-way trade reaching 203.6 billion USD in 2022.[civ] Chew (2021) provides an intriguing perspective, suggesting that Malaysia views its relationship with China as multifaceted due to its importance for Malaysia’s future socio-economic development.[cv] This stance challenges the notion that the South China Sea conflict solely determines Malaysia-China bilateral relations. For instance, the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA), signed in 2002, played a major role in establishing stronger trade ties due to eliminating tariffs on goods and service trades.[cvi]

In the context of investment, a similar trend is observed in China’s economic importance to Malaysia. China has held the position of Malaysia’s leading investor since 2016. This aligns with Malaysia’s goal of advancing infrastructural development, complemented by opportunities generated from BRI investments. Notable Chinese investments in Malaysia include projects like the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), connecting the East and West Coasts of Peninsular Malaysia,[cvii] and the 2021 construction of the Batang Saribas Bridge.[cviii] Prominent Chinese companies, including LONGi Solar Technology, Huawei Technologies, and Alibaba Group Holding, have chosen to invest in Malaysia, attracted by favorable service tariffs facilitated by the ACFTA There is a distinct connection between Malaysia’s understated approach to the South China Sea crisis and the investment and trade opportunities generated by China.[cix]

Malaysia’s adoption of triadic maritime diplomacy in the South China Sea stems from the necessity to secure and bolster economic ties with China. Malaysia’s primary political interest focuses on ensuring China’s continued role as Malaysia’s top trading and investment partner, especially amidst ongoing security concerns in the South China Sea.[cx] Malaysia recognizes that the crisis unfolding in the South China Sea remains under the grey zone area, making it challenging to address it through a legal or international law-based approach. Given the situation’s complexity, Malaysia is taking a cautious stance, avoiding action that could provoke China.[cxi] Instead, it adopts a minimalist approach to demonstrate flexibility in open negotiation and capacity-building measures. By adopting coercive maritime diplomatic tactics, Malaysia accentuates the significance of the South China Sea claims to domestic constituencies and assures the public of its steadfastness in safeguarding the country’s sovereignty at sea.[cxii] Through persuasive and co-operative maritime diplomacy, Malaysia aligns its policies with regional allies, seeking sustainable maritime security. It also signals its commitment to defend its maritime jurisdictional waters in accordance with established international laws. As stated by Anwar Ibrahim during a keynote address at the 36th Asia-Pacific Roundtable in 2023, “…Malaysia has always advocated for peaceful and constructive settlement of all disputes, in line with international laws’ recognized norms and principles, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.”[cxiii] Through these seemingly contradictory stances, Malaysia both advances its Kasawari Gas Development Project and conveys its friendly intentions to Beijing.

Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies in the South China Sea can also be understood through the lens of its hedging policies in its foreign policy alignment. Scholars have extensively discussed the foreign policy alignment strategies of Malaysia and other Southeast Asian states, commonly identifying hedging as a prevalent approach.[cxiv] Hedging involves pursuing a non-aligned stance while exhibiting alignment-ambiguous policies to offset the risks associated with great power alignment and maximize the potential benefits.[cxv] In Malaysia’s case, the U.S. has consistently held a pivotal role as its primary defence partner, even in light of Malaysia’s robust trade and investment relations with China. For instance, Malaysia maintains a close defence partnership with these nations despite initial concerns about the trilateral security pact between the US, Australia, and the UK (AUKUS). This is exemplified in the joint exercises conducted between Malaysia and the U.S., highlighting the potential for stronger cooperation between Malaysia and the U.S. and its allies. Simultaneously, Malaysia’s defensive bilateral relations with China have remained steadfast since 2014. Despite differences at sea, China’s and Malaysia’s armed forces have consistently engaged in annual bilateral exercises from 2014 to 2018.[cxvi]

The foundations of this hedging policy by Malaysia are illustrated by the country’s refusal to acknowledge the existence of a dispute with China, as evidenced by Malaysia’s note verbale exchanges between 2019 and 2020.[cxvii] This position provides Malaysia with the flexibility it needs, as it refrains from adopting a decisive South China Sea policy that would bind its action. Malaysia’s triadic maritime diplomacy, coupled with the non-confrontational signals, projects an image of non-opposition to China, thereby paving the way for continued productive bilateral relations within their multifaceted bilateral relationship.

Malaysia can push forward conflict resolution mechanisms and tension management under ASEAN by downplaying the South China Sea disputes. Part of Malaysia’s strategy involves maintaining a non-decisive and flexible stance for Malaysia. This can be achieved by echoing the crucial role of ASEAN in managing tensions and potentially assisting in conflict resolution in the South China Sea. As outlined by the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia is committed to peaceful measures to resolve the tensions, with reference to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[cxviii] By advocating for an ASEAN-based resolution, Malaysia could achieve its goal of avoiding a decisive and assertive maritime diplomatic strategy regarding the South China Sea. ASEAN-based solutions prioritize amity, cooperation, consensus, and co-operative values, all of which align with Malaysia’s interests in maintaining cordial relations with China while maintaining distinct boundaries.

Malaysia has repeatedly referred to the ASEAN’s long-negotiated Code of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (COC).[cxix] Malaysia still believes there is potential to finalize the COC as the principal legal instrument for managing tensions in the disputed waters. Its commitment to concluding a COC and temporarily adhering to the existing Code of Conduct Declaration showcases Malaysia’s genuine intent to downplay the South China Sea issue. This is because the COC negotiations have remained in stalemate for two decades, making it unlikely for a resolution to be reached in the coming years.[cxx] By consistently endorsing the COC and ASEAN-based resolution approaches to address the crisis, Malaysia actively promotes diplomatic efforts to resolve tensions that threaten its sovereignty while also recognizing that there may be no need to adopt a decisive South China Sea policy for several years to come.

What arguably sets Malaysia apart from its Southeast Asian claimants is its distinctive foreign policy approach when countering China’s aggression within its national jurisdictional waters. Malaysia has chosen a strategy that aims to de-escalate emerging crises by avoiding tensions and confrontations at sea. Even in the face of frequent intrusions by the CCG and maritime militia vessels, Malaysia has generally downplayed the incidents. It does not perceive them as overt provocations as long as they do not disrupt the country’s ongoing exploration and drilling operations of hydrocarbon resources.

Nonetheless, this foreign policy orientation has shifted in recent years due to Malaysia’s Kasawari Gas Development Project. It appears that securing hydrocarbon resources in the oil and gas fields in the South China Sea holds paramount importance for Malaysia, regardless of its potential to cause irritants in the country’s relations with China. This foreign policy priority has garnered strong support from local political elites and government officials, with many of them perceiving this as the way forward for ensuring the country’s energy security for decades ahead.

Despite the fact that the Malaysian government has often maintained a low-key rhetoric in dealing with China’s aggressions, incidents of intrusions and assertive actions in Malaysia’s EEZ areas by China’s coast guard, government agencies, and maritime militia ships have increasingly become the norm. These situations have compelled Malaysian policymakers to adopt an assertive stance in response to these incidents. Consequently, Malaysia has introduced a more proactive naval presence within its EEZ waters to safeguard its sovereign rights while still pursuing a diplomatic path, seeking negotiation, and refraining from escalating tensions. This article investigates this intriguing development by probing how Malaysia manages these seemingly contradictory policies, thereby shedding light on the country’s current stance regarding the South China Sea, especially after the first discovery of the lucrative gas reserves in the Kasawari gas field in 2011.

First, this article contends that the dynamics of Malaysia’s response to the South China Sea conflict have undergone a significant transformation. This shift is primarily attributed to Malaysia’s accelerated efforts in advancing the Kasawari Gas Development Project, which has drawn Beijing’s attention and retaliation. Consequently, China’s assertive responses via CCG and maritime militia vessels have escalated in recent years. Several cases reported by the AMTI provide evidence of a steady rise of Chinese aggression at sea, particularly near the contested Luconia Shoals. China’s confrontational approach has also influenced Malaysia’s perspective on geopolitical tensions, leading to a modified approach and strategy for adapting to emerging crises.

Consequently, this article identifies a contradictory policy in Malaysia’s response to the South China Sea crisis. On the one hand, it seeks to appease its domestic constituents and uphold traditional maritime security principles in its South China Sea claims by deploying hard-power maritime assets, like the navy, for patrolling functions. On the other hand, Malaysia continues to downplay the crisis, demonstrating a willingness to engage in negotiations and deny the existence of a territorial dispute between Malaysia and China.

Second, this study draws on Le Mière’s concept of maritime diplomacy to argue that Malaysia employs a combination of coercive, persuasive, and co-operative maritime diplomatic strategies, which are collectively termed “triadic maritime diplomacy.” Coercive maritime diplomatic strategies are exemplified by Malaysia’s ongoing use of its hard-power assets, such as the navy, to compel and deter adversaries at sea. Malaysia’s persuasive maritime diplomatic strategy is evident through its naval forces’ active and compelling presence in the contiguous zones. Lastly, its co-operative maritime diplomacy signals Malaysia’s willingness to collaborate and align interests to enhance maritime security, as demonstrated through joint naval exercises and maritime security agency drills with partner nations. Malaysia’s maritime diplomatic strategies empowered them to selectively downplay the South China Sea dispute in certain scenarios while adopting a resolute posture in others.

Thirdly, this article posits that this seemingly contradictory policy serves a dual purpose of accommodating future economic opportunities involving China and signalling non-alignment with major global powers. China stands as Malaysia’s foremost trading partner and leading investor. By employing diverse maritime diplomatic strategies, Malaysia avoids the need for hasty conflict resolution, thereby enabling the continuation of trade relations between the two countries. Additionally, Malaysia’s non-aligned stance is maintained when engaging with Western nations in most of its defence relations, while also balancing its economic and relatively limited defence relations with China. Ultimately, Malaysia’s consistent rhetoric in support of ASEAN-based mechanisms, i.e. the Code of Conduct, allows it to sustain a contradictory policy vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea dispute.

This article supports those assumptions in connection to existing studies that interpret Malaysia’s foreign policies vis-à-vis China as hedging. Hedging can take many different forms, and this article shows that certain maritime diplomatic policies, such as those engaged by Malaysia in the Kasawari gas fields, are also forms of hedging. The main argument held by hedging scholars is that states adopt contradictory policies to offset the risks of alignment. The triadic maritime diplomacy of Malaysia also consists of a decisive policy to counter sea-based intrusions into Malaysian territory, coupled with actions and rhetoric that downplay the crisis due to the need of Kuala Lumpur to secure China’s lucrative economic opportunities.

[i] Parameswaran Prashanth, Playing It Safe: Malaysia’s Approach to the South China Sea and Implications for the United States, (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2015), accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/189746/CNAS%20Maritime%206_Parameswaran_Final.pdf

[ii] Data from the U.S. Energy Information Agency (updated in 2019) concludes that the South China Sea consists of 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and a potential of 11 billion barrels of oil.

[iii] “Rocks, Reefs, Submerged Shoals – Who Claims or Occupies Them?” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, accessed March 25, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/scs-features-map/

[iv] Ketian Zhang, “Explaining China’s large-scale land reclamation in the South China Sea: Timing and Rationale,” Journal of Strategic Studies 46, no. 6-7 (2023): 1-6; Hoo Tiang Boon, “Hardening the Hard, Softening the Soft: Assertiveness and China’s Regional Strategy,” Journal of Strategic Studies 40, no. 5 (2016): 639-662.

[v] James R. Holmes, “Strategic Features of the South China Sea: A Tough Neighborhood for Hegemons,” Naval War College Review 67, no. 2 (2014): 1-23; Bama Andika Putra, “Gauging Contemporary Maritime Tensions in the North Natuna Seas: Deciphering China’s Maritime Diplomatic Strategies,” The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Civic and Political Studies 17, no. 2 (2022): 85-99.

[vi] Neil Jerome Morales, “Philippines rebukes Beijing for ‘dangerous manoeuvres’ in South China Sea,” Reuters, April 28, 2023, accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-reports-confrontation-with-chinese-vessels-south-china-sea-2023-04-28/

[vii] James Pearson and Khanh Vu, “Vietnam mulls legal action over South China Sea dispute,” Reuters, November 6, 2019, accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnam-southchinasea-idUSKBN1XG1D6/

[viii] Mohammad Zaki Ahmad and Mohd Azizuddin Mohd Sani, “China’s Assertiveness Posture in Reinforcing its Territorial and Sovereignty Claims in the South China Sea: An Insight into Malaysia’s Stance,” Japanese Journal of Political Science 18, no. 1 (2017): 67-105.

[ix] James Shoal (Gugusan Beting Serupai) is located 45 nautical miles off the coast of Sarawak, and the Luconia Shoals (Gugusan Beting Patinggi Ali), positioned 62 nautical miles from Sarawak. See, Ahmad and Sani, “China Assertiveness Posture,” 67-69.

[x] Vivian Louis Forbes, “Navigating Malaysia-China geopolitical relations,” Australian Naval Institute, September 10, 2017, accessed November 25, 2023. https://navalinstitute.com.au/navigating-malaysia-china-geopolitical-relations/

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Luconia Shoals is one of the largest reef complexes in the South China Sea. It is situated 62 miles off the Sarawak coast, and located in the farthest southwestern end of Spratly Islands. See, J. Ashley Roach, Malaysia and Brunei: An Analysis of their Claims in the South China Sea (Virginia: CAN, 2014), accessed November 21, 2023. https://www.cna.org/reports/2014/malaysia-and-brunei-claims-in-scs

[xiii] The Malaysian oil and gas company, PETRONAS, estimates that the Luconia Shoals consist of 3.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves. The Kasawari gas field will start its production phase in 2023. See, “Kasawari Gas Development Project, Sarawak, Malaysia,” Offshore Technology, February 10, 2023, accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/kasawari-gas-development-project-sarawak/?cf-view

[xiv] “Contest at Kasawari: Another Malaysian Gas Project Faces Pressure,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, July 7, 2021, accessed November 23, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/contest-at-kasawari-another-malaysian-gas-project-faces-pressure/

[xv] Ani, “Chinese coast guard vessels harass Malaysian oil, gas development work off Sarawak: US think tank,” Economic Times, July 11, 2021, accessed November 21, 2023. https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/oil-and-gas/chinese-coast-guard-vessels-harass-malaysian-oil-gas-development-work-off-sarawak-us-think-tank/84309999; Amanda Battersby, “Chinese “harassment” around Malaysian offshore assets stirs tensions,” Up Stream Online, July 15, 2021, accessed November 21, 2023. https://www.upstreamonline.com/politics/chinese-harassment-around-malaysian-offshore-assets-stirs-tensions/2-1-1039115

[xvi] Bonny Lion, et al., described China’s grey zone tactics as “…measures that powerful countries have employed both historically and in recent decades that are beyond normal diplomacy and other traditional approaches to statecraft but short of direct use of military force for escalation or a conflict.” For details, see Bonny Lion, et al., A New Framework for Understanding and Countering Gray Zone Tactics (Santa Monica: RAND Corporations, 2022), accessed November 12, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA594-1.html

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Rob McLaughlin, “The Law of the Sea and PRC Gray-Zone Operations in the South China Sea,” American Journal of International Law 116, no. 4 (2022): 821-835.

[xix] Carl Thayer, “Chinese coercive activities persist in one of Asia’s hottest flashpoints,” The Diplomat, November 1, 2019, accessed November 27, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2019/10/a-difficult-summer-in-the-south-china-sea/

[xx] Rozanna Latiff and A. Ananthalakshmi, “Malaysian oil exploration vessel leaves South China Sea waters after standoff,” Reuters, May 12, 2020, accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-security-malaysia/malaysian-oil-exploration-vessel-leaves-south-china-sea-waters-after-standoff-idUSKBN22O1M9/

[xxi] Ian Storey, “Malaysia and the South China Sea Dispute: Policy Continuity amid Domestic Political Change,” Singapore: ISEAS Perspective, March 20, 2020, accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ISEAS_Perspective_2020_18.pdf

[xxii] China has been persistent to defend its stance of claiming the nine-dash line, including rights over exploring oil and gas reserves within those waters. Instances of Malaysia’s intentions to explore and extract those reserves have been met with fury. See, Amy Chew, “Malaysia’s energy needs face Chinese pushback in South China Sea,” Al Jazeera, April 25, 2023, accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2023/4/25/malaysian-energy-needs-clash-with-china-claims-in-south-china-sea

[xxiii] Leszek Buszynski, “Introduction: The Development of South China Sea Dispute,” in The South China Sea Maritime Dispute: Political, Legal and Regional Perspectives, eds. Leszek Buszynski and Do Thanh Hai (New York: Routledge, 2014), 1-10.

[xxiv] Joseph Sipalan, “Malaysia to summon Chinese envoy over ‘suspicious’ air force activity,” Reuters, June 2, 2021, accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysia-says-chinese-military-planes-came-close-violating-airspace-2021-06-01/

[xxv] Sulhi Khalid, “China denies Malaysia’s intrusion charge, says military aircraft were engaged in routine training,” The Edge Malaysia, June 2, 2021, accessed November 11, 2023. https://theedgemalaysia.com/article/china-denies-malaysias-intrusion-charge-says-military-aircraft-were-engaged-routine-training

[xxvi] Prashanth, Managing the Rise of Southeast Asia’s Coast Guards (Washington, DC: Wilson Center, 2019), accessed 21 February 2023. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/managing-the-rise-southeast-asias-coast-guards

[xxvii] There is a growing number of studies focusing on the maritime diplomatic use of maritime constabulary forces in grey zone areas. The scope of analysis is currently focused within the context of Southeast Asian states. See, Putra, “The Golden Age of White Hulls: Deciphering the Philippines’ Maritime Diplomatic Strategies in the South China Sea,” Social Sciences 12, no. 6 (2023): 1-14; Putra “The rise of paragunboat diplomacy as a maritime diplomatic instrument: Indonesia’s constabulary forces and tensions in the North Natuna Seas,” Asian Journal of Political Sciences 31, no. 2 (2023): 106-124; Putra, “Rise of Constabulary Maritime Agencies in Southeast Asia: Vietnam’s Paragunboat Diplomacy in the North Natuna Seas,” Social Sciences 12, no. 4 (2023): 1-15.

[xxviii] Yew Meng Lai and Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “Structural sources of Malaysia’s South China Sea policy: power uncertainties and small-state hedging,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 75, no. 3 (2020): 672-693.

[xxix] Elina Noor and T. N. Qistina, “Great Power Rivalries, Domestic Politics and Malaysian Foreign Policy,” Asian Security 13, no. 3 (2017): 200-219.

[xxx] Chow-Bing Ngeow, “Malaysia’s China Policy and the South China Sea Dispute Under the Najib Administration (2009-2018): A Domestic Policy Process Approach,” Asian Politics & Policy 11, no. 4 (2019): 586-605.

[xxxi] Storey, “Malaysia and the South China Sea Dispute”; Chew, “Malaysia’s energy needs face Chinese pushback”; Emirza Adi Syailendra, “The Sense and Sensibility of Malaysia’s Approach to its Maritime Boundary Disputes,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, November 21, 2022. https://amti.csis.org/the-sense-and-sensibility-of-malaysias-approach-to-its-maritime-boundary-disputes/

[xxxii] Ahmad and Sani, “China’s Assertiveness Posture”; Parameswaran, Playing It Safe; Adam Leong Kok Wey, “A small state’s foreign affairs strategy: Making sense of Malaysia’s strategic response to the South China Sea debacle,” Comparative Strategy 36, no. 5 (2017): 392-399.

[xxxiii] Elina Noor, “The South China Sea Dispute: Options for Malaysia,” in The South China Sea Dispute: Navigating Diplomatic and Strategic Tensions, ed., Ian Storey and Cheng-Yi Lin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 205-227.

[xxxiv] Syailendra, “Why Don’t Malaysian Policymakers View China as a Threat?” The Diplomat, February 24, 2023, accessed November 29, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/02/why-dont-malaysian-policymakers-view-china-as-a-threat/

[xxxv] Anthony Milner and Siti Munirah Kasim, “Beyond Sovereignty: Non-Western International Relations in Malaysia’s Foreign Relations,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 40, no. 3 (2018): 371-396; Anthony Milner, “‘Sovereignty’ and Normative Integration in the South China Sea: Some Malaysian and Malay Perspectives,” in Southeast Asia and China, eds. Lowell Dittmer and Ngeow Chow Bing (Singapore: World Scientific, 2017): 229-246.

[xxxvi] Christian Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century: Drivers and Challenges (New York: Routledge, 2014): 7.

[xxxvii] Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (New York: Routledge, 2018); Bob Davidson, “Modern Naval Diplomacy: A Practitioner’s View,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 11, no. 1-2 (2009): 1-47.

[xxxviii] James Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1991: Political Applications of Limited Naval Force (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1994); Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1898).

[xxxix] Edward Luttwak, The Political Uses of Sea Power (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1974).

[xl] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[xli] Le Mière, “The Return of Gunboat Diplomacy,” Survival 53, no. 5 (2011): 53-68.

[xlii] Bing, “Malaysia-China Defence Ties: Managing Feud in the South China Sea,” RSIS Commentary, May 26, 2022. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/malaysia-china-defence-ties-managing-feud-in-the-south-china-sea/?doing_wp_cron=1701167417.2169001102447509765625

[xliii] “Rocks, Reefs, Submerged Shoals.”

[xliv] Chew, “Malaysia’s energy needs.”

[xlv] Amanda Battersby, Nishant Ugal, and Russell Searancke, “Petronas awards dual FEED contracts for world’s largest offshore CCS project,” Upstream, February 16, 2022. https://www.upstreamonline.com/exclusive/petronas-awards-dual-feed-contracts-for-worlds-largest-offshore-ccs-project/2-1-1167988

[xlvi] Alex Procyk, “Petronas discovers gas offshore Sarawak,” The Borneo Post, December 7, 2023, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.theborneopost.com/2012/02/14/petronas-discovers-gas-offshore-sarawak-2/

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] “Kasawari Gas Development Project.”

[xlix] “Oil & gas field profile: Kasawari Conventional Gas Field, Malaysia,” Offshore Technology, updated February 17, 2024, accessed 28 November 2023, https://www.offshore-technology.com/data-insights/oil-gas-field-profile-kasawari-conventional-gas-field-malaysia/?cf-view

[l] “Analyst Cautions Malaysians to Brace Against Energy Crisis,” Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, June 13, 2022, accessed November 15, 2023, https://mier.org.my/analyst-cautions-malaysians-to-brace-against-energy-crisis-energy-watch/

[li] Malaysian Ministry of Economy, National Energy Transition Roadmap: Energising the Nation, Powering Our Future (Putrajaya: Ministry of Economy, 2023), accessed 26 November 2023. https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/202309

/National%20Energy%20Transition%20Roadmap_0.pdf

[lii] Chew, “Malaysia energy needs.”

[liii] “Flooding the Zone: China Coast Guard Patrols in 2022,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, January 30, 2023, accessed November 27, 2023, https://amti.csis.org/flooding-the-zone-china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2022/

[liv] Imam Muttaqin Yusof and Nisha David, “Malaysian, Japanese coast guard hold South China Sea security drill,” Radio Free Asia, January 13, 2023, accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/southchinasea/malaysiajapandrills-01132023133204.html

[lv] In multiple cases of China Coast Guard patrols in the Luconia Shoals between 2019 and 2023, the CCG would maintain a prolonged position in Malaysian waters. Due to its close proximity to Malaysia’s territorial sea, the RMN has been deployed to tail CCGs in those instances, as China’s operations have disrupted the work taking place in the Kasawari gas field. See, “Still on the Beat: China Coast Guard Patrols in 2020,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, December 4, 2020, accessed November 10, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/still-on-the-beat-china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2020/; “Flooding the Zone.”

[lvi] See Putra, “The Golden Age of White Hulls,” 1-14; Putra, “The rise of paragunboat diplomacy” 106-124; Putra, “Rise of Constabulary Maritime Agencies,” 1-15.

[lvii] Yang Fang, “Coast guard competition could cause conflict in the South China Sea,” East Asia Forum, October 27, 2018, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/10/27/coast-guard-competition-could-cause-conflict-in-the-south-china-sea/

[lviii] See, “Contest at Kasawari”; “Perilous Prospects: Tensions Flare at Malaysian, Vietnamese Oil and Gas Fields,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, March 30, 2023, accessed March 30 2023. https://amti.csis.org/perilous-prospects-tensions-flare-at-malaysian-vietnamese-oil-and-gas-fields/; “China and Malaysia in Another Staredown Over Offshore Drilling,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, November 25, 2020, accessed March 30, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/china-and-malaysia-in-another-staredown-over-offshore-drilling/

[lix] See, “Contest at Kasawari.”

[lx] “Malaysia Picks a Three-Way Fight in the South China Sea,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, February 21, 2020, accessed November 29, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/malaysia-picks-a-three-way-fight-in-the-south-china-sea/

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] See, “Perilous Prospects.”

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ministry of Foreign Affairs Malasia, “Malaysia’s Position on the South China Sea,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs Malaysia, April 8, 2023, accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.kln.gov.my/web/guest/-/malaysia-s-position-on-the-south-china-sea

[lxv] Storey, “Malaysia and the South China Sea.”

[lxvi] A. Ananthalakshmi, “Malaysia says it will protect its rights in the South China Sea,” Reuters, April 8, 2023, accessed March 10, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysia-says-it-will-protect-its-rights-south-china-sea-2023-04-08/

[lxvii] The Chinese Ambassador to Malaysia, Ouyang Yujing, stated that China has been Malaysia’s largest trading partner for 14 consecutive years. See, “Malaysia-China bilateral trade hit record US$203.6b in 2022, says Chinese ambassador,” Malaysian Investment Development Authority, February 17, 2023, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.mida.gov.my/mida-news/malaysia-china-bilateral-trade-hit-record-us203-6b-in-2022-says-chinese-ambassador/

[lxviii] Chew, “Malaysia’s energy needs.”

[lxix] Rao Aimin, “Malaysia ready to negotiate with China on South China Sea: Anwar,” The Jakarta Post, April 3, 2023, accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.thejakartapost.com/world/2023/04/03/malaysia-ready-to-negotiate-with-china-on-south-china-sea-anwar.html

[lxx] Anwar’s statement was interpreted by Malaysia’s main opposition party as recognizing the presence of China’s sovereignty in the South China Sea. The Bersatu Party, which head the Perikatan coalition, expressed their concerns, claiming that Anwar’s statement was irresponsible and undermines Malaysia’s sovereignty. See, Ili Shazwani, “Malaysian opposition slams PM for ‘reckless’ South China Sea statement to Beijing,” Benar News, April 7, 2023, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/malaysian/muhyiddin-slams-anwar-south-china-sea-04072023133207.html

[lxxi] Amy Chew, “Malaysia must shift from ‘jungle warfare’ to keep eye on Chinese boats in South China Sea, militants, as maritime threats rise,” South China Morning Post, January 24, 2022, accessed February 12, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3164457/malaysia-must-shift-jungle-warfare-keep-eye-chinese-boats

[lxxii] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[lxxiii] Tharishini Krishnan, “Malaysia’s Conceptualization of Maritime Security,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, November 22, 2021, accessed January 21, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/malaysias-conceptualization-of-maritime-security/

[lxxiv] The MMEA was established in 2004 under the Maritime Enforcement Agency Act of 2004 (Act 663), initially placed under the Prime Minister’s Department. The MMEA is mandated with contemporary coast guarding roles, which include maintaining law and order at sea, marine border protection, and the conduct of search and rescue functions. See, Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency, “Latar Belakang,” Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency, February 1, 2021, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.mmea.gov.my/eng/index.php/en/mengenai-kami-2/latar-belakang

[lxxv] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[lxxvi] S. Adie Zul, Nisha David, Dizhwar Bukhari, and Muzliza Mustafa, “Analysts: Malaysia’s Navy Drill Sends Strong Message to South China Sea Claimants,” Radio Free Asia, August 20, 2021, accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/malaysia-drill-08202021155721.html

[lxxvii] See, Till, Seapower; Davidson, “Modern Naval Diplomacy”; Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy.

[lxxviii] The naval exercise “Taming Sari” lasted six days, consisted of a live launch of an anti-ship missile (through Malaysia’s navy submarine KD Tun Razak), and the launch of guided missiles by the RMN’s KD Lekiu and KD Lekir.

[lxxix] “Analysts: Malaysia’s Navy Drill.”

[lxxx] The closest RMN port is the Kuching patrol vessel base located in Sarawak.

[lxxxi] Parameswaran, “Assessing Malaysia’s Coast Guard in ASEAN Perspective,” The Diplomat, May 2, 2017, accessed February 29, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2017/05/assessing-malaysias-coast-guard-in-asean-perspective/; Jim Dolbow, “Malaysia Coast Guard Is One to Watch,” U.S. Naval Institute, April 2018, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018/april/malaysia-coast-guard-one-watch

[lxxxii] Putra, “The rise of paragunboat diplomacy,” 106-124.

[lxxxiii] Putra, “Rise of Constabulary Maritime Agencies,” 1-15.

[lxxxiv] Putra, “The Golden Age of White Hulls,” 1-14.

[lxxxv] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[lxxxvi] See, Krishnan, “Malaysia’s Conceptualization.”

[lxxxvii] In the past, Theodore Roosevelt’s “Great White Fleet” that navigated globally between 1907 and 1909 is a clear of example of a state’s intent in showcasing a state’s maritime-based hard power assets.

[lxxxviii] Storey, “Malaysia and the South China Sea Dispute.”

[lxxxix] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[xc] Ibid.

[xci] “US and RMN navies conduct bilateral exercise MTA Malaysia 2017,” Naval Technology, September 20, 2017, accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.naval-technology.com/news/newsus-and-malaysian-navies-begin-bilateral-mta-exercise-this-year-5929965/; “US and Malaysian navies conduct bilateral exercise ‘MTA Malaysia 2021’,” Naval Technology, November 24, 2021, accessed March 30, 2023, https://www.naval-technology.com/news/us-malaysia-exercise-mta-malaysia-2021/?cf-view

[xcii] “First ASEAN-US Maritime Exercise Successfully Concludes,” Commander U.S 7th Fleet, September 6, 2019, accessed February 25, 2023. https://www.c7f.navy.mil/Media/News/Display/Article/1954403/first-asean-us-maritime-exercise-successfully-concludes/

[xciii] “Singapore and Malaysia Navies Conclude 30th Edition of Bilateral Naval Exercise Malapura,” MINDEF Singapore, November 14, 2022, accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.mindef.gov.sg/web/portal/mindef/news-and-events/latest-releases/article-detail/2022/November/14nov22_nr; Kukuh S. Wibowo, “Indonesia, Malaysia Conduct Joint Military Exercise in Java Sea,” Tempo, August 29, 2022, accessed March 30, 2023. https://en.tempo.co/read/1628179/indonesia-malaysia-conduct-joint-military-exercise-in-java-sea; Durie Rainer Fong, “Bintulu naval base a must for Malaysia’s security in South China Sea, says Bongowan rep.,” The Star, March 21, 2023, accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/03/21/bintulu-naval-base-a-must-for-malaysia039s-security-in-south-china-sea-says-bongowan-rep

[xciv] Yusof and David, “Malaysian, Japanese coast guard.”

[xcv] Dolbow, “Malaysia Coast Guard.”

[xcvi] Chew, “Malaysia must shift.”

[xcvii] Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency, “Visi dan Misi,” Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency, accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.mmea.gov.my/eng/index.php/ms/mengenai-kami-2/visi-misi

[xcviii] Putra, “Rise of Constabulary Maritime Agencies,” 1-15.

[xcix] Le Mière, Maritime Diplomacy.

[c] Darwis and Bama Andika Putra, “Construing Indonesia’s Maritime Diplomatic Strategies against Vietnam’s Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing in the North Natuna Sea,” Asian Affairs: An American Review 49, no. 4 (2022): 172-192.

[ci] Jay Batongbacal, “The Philippines’ Conceptualization of Maritime Security,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, November 4, 2021, accessed January 10, 2023. https://amti.csis.org/philippine-conceptualization-of-maritime-security/

[cii] “Flooding the Zone.”