Cem Birol, Koç University VPRI Office

Abstract

Economic Norms Theory (ENT) implies that anti-modernist and anti-market values flourish in countries where the central authority poorly monitors contracts that bind economic transactions. Decades of research show that ENT astutely predicts civil war and interstate war incidents, as well as people’s support for war, and suicide bombing in defense of Islam. This paper investigates the association between contract enforcement and anti-Americanism, which is the ENT’s core, yet is a statistically under-evaluated implication. Accordingly, in countries with poor economic contract monitoring, power-contending elites can attribute the resultant loss of prosperity to the USA and relatedly spread anti-American values among citizens. It is the urban poor who are cognitively most available to adopt such elite-driven anti-Americanism since they tend to be hurt most socially and economically by unfulfilled market contracts. To investigate this argument, I statistically estimate random intercept models on a sample of Pew Global Attitudes Project’s 2013 survey results. I observe that a three-way interaction among individuals’ urbanity, poverty, and their nations’ poor contract enforcement indicators increase anti-Americanism.

1. Introduction

Early in the 2000s, when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became Turkey’s Prime Minister, his opposition blamed the United States for supporting his journey towards political authority. Erdoğan was dismissive of these accusations and called it a baseless conspiracy. In 2013, millions of Turks participated in the Gezi Park protests against Erdoğan. This time, it was Erdoğan who blamed the USA for organizing and supporting demonstrations against his rule. Meanwhile, Erdoğan’s opposition ironically considered him as a believer in conspiracies. Yet, it was this very opposition who blamed the USA for supporting Erdoğan a decade ago. Whoever did the promoting, the elite-originated anti-American discourses had dire consequences for the USA’s image in Turkey. A 2018 survey conducted by Kadir Has University shows that around 82% of Turks see the United States as a threat.

Pew global surveys[i] also indicate that Turkey often has one of the greatest shares of respondents that report somewhat or very unfavorable opinions toward the USA.[ii] In the meantime, as a NATO member, Turkey continues to make foreign policy moves such as the purchase of S-400 missile defense systems from Russia at the expense of upsetting American policymakers. Erdoğan likely has little trouble convincing a considerable share of Turks with regards to policies that antagonize the USA, such as the S-400 purchase.[iii]

The case of Turkey illustrates how high levels of anti-Americanism are related more to political elites’ strategic use of conspiratorial ideas about the USA than actual US foreign policy choices.[iv] Yet, why do Turkish elites, and for that matter, many other elites, focus this much on antagonizing the USA and pointing to its supposed collaborators? While elite-driven polarization in a country is nothing new, only certain elites in certain countries appear to strategize around the promotion of unsubstantiated ideas that target the USA. From a logical standpoint, if certain elites strategically choose anti-Americanism, they must be doing so because they anticipate a large enough target audience that will buy into their strategy. Accordingly, there are two related questions: what countries are most likely to provide the scene for inter-elite competition that results in the promotion of anti-Americanism, and what target audience is most likely to buy into this strategy? Given that Muslims show significant variance in their anti-American attitudes, it is challenging to suggest that any Islamic society constitutes a viable target audience for elites to promote anti-Americanism.[v] Thus, more theoretical effort is potentially needed to clarify why certain audiences seem more available than others for the elites to spread anti-Americanism.

In this paper, I argue that central authorities’ inability to monitor market transactions generates a loss of societal prosperity, which eventually leaves certain segments of populations available to adopt anti-Americanism. To that end, I rely on the theoretical framework in Michael Mousseau’s Economic Norms Theory (ENT).[vi] The core implication of the ENT is that regulations for economic exchanges in a society shape peoples’ values and norms. When market transactions are poorly monitored by the central government, the urbanites who suffer from the resultant loss of prosperity seek a scapegoat that symbolizes market economies. In a quest to maximize their popular support, political elites can portray the USA as the urban poor’s source of economic suffering and point to rival elites as US collaborators, or worse, puppets.

To investigate the empirical relevance of Mousseau’s theory, I use a sample of respondents from 38 nations by Pew Global Attitudes Project’s 2013 Survey. As part of my statistical investigations, I implement random intercepts models. In line with ENT, the results suggest that higher levels of poverty suffered by urbanites lead to greater levels of anti-American attitudes only in countries with lower than global median life insurance holdings per capita. I also replicate these results with the Pew 2002 survey, and through different variable operationalization approaches. In all my empirical analyses, I also re-evaluate recent findings with regards to how US foreign policy choices can directly affect people’s bias towards the USA.[vii] I observe that findings with regards to the ENT appear to be most robust vis-à-vis these alternatives.

An important question is why the ENT matters in the study of anti-Americanism. The ENT proves to be a useful theoretical framework in making sense of support for suicide bombing in defense of Islam, terrorist incidents, and people’s support for their governments’ war involvement.[viii] Arguments developed in these inquiries converge in the notion that failed economic markets push people to buy into anti-market and anti-modernity ideas. As implied in Mousseau’s original theoretical work, the study of anti-Americanism is likely one of the most direct means to validate the core implications of ENT.[ix] Accordingly, not only does the present paper build on previous elite-based explanations of Anti-Americanism, it also constitutes one of the most direct investigations of Mousseau’s theory.

In what follows, I first present a brief overview of the scholarly work on anti-Americanism. Next, I describe Mousseau’s theory. Third, I lay out the research design and the empirical results. Finally, I discuss the implications of the present findings and highlight venues for future research.

Anti-Americanism represents a negative bias in people’s cognition when they are asked to evaluate any concept pertaining to the USA, such as American people, culture, foreign policy, entertainment, businesses, and/or economic systems. As Katzenstein and Keohane put, anti-Americanism cannot be limited to substantive assessment of US foreign policy choices. It is rather a cognitive process that distorts people’s ability to make informed inferences on the USA.[x] Thus, while people can be critical of US foreign policy choices, this does not directly make them anti-American. If a person sees every action committed by the USA as malicious or at least suspicious, they might be driven by a certain level of bias that is relatable to anti-Americanism.

Not everyone strongly buys into the notion that anti-Americanism is a pure form of bias. Many scholars still investigate the extent to which the USA’s overseas agenda directly plays a role in shaping people’s attitudes.[xi] Some researchers, in fact, dismiss the notion of “bias” and see the Bush Administration’s War on Terror campaign as the main reason for the rise of anti-Americanism in the 21st Century.[xii] Empirical analyses show that people in the Islamic world are typically found to express concerns about the American unilateral foreign policy direction and dismissal of intergovernmental organizations.[xiii]

It is, however, likely that US foreign policy cannot be a sufficient reason behind surges in anti-American attitudes. Decades of research efforts imply that people’s ideological, psychological, and social predispositions, as well as how they receive their information, significantly matter in shaping their political opinions.[xiv] In that regard, Nisbet and Myers’ survey analyses suggest that Arab anti-Americanism and concerns for US foreign policy choices are closely associated with media exposure and political affiliation.[xv] In the case of Turkey, local media agents tend to portray American actions far more negatively than the international media, which explains why Turks worry about unilateral American actions despite their nation being one of the oldest NATO members.[xvi] Hence, people rarely formulate their opinion on the USA in a vacuum, showing that factors such as how the media portrays the USA play a noteworthy role in this process.[xvii]

Media framing, however, is unlikely to be independent of elite politics. Typically, media sources directly or indirectly reflect the opinions of political or social elites they support. Relatedly, several scholars suggest that anti-Americanism is a function of elite polarization.[xviii] As the Turkish example in the introduction of this manuscript alludes to, the USA can be portrayed by certain elites as an evil conspirator. This is not because the USA is evil per se, but elites choose to simplify otherwise complex political processes for their supporters by faulting the USA.[xix] As elites favor anti-American tones, the greater share of their audiences is exposed to anti-American information, which is theoretically a recipe for people to form strong opinions about the USA.[xx] Relatedly, Blaydes and Linzer show that anti-Americanism in the Islamic world is more prevalent in nations with greater competition between secular and traditionalist elites.[xxi]

The inter-elite competition perspective in the study of anti-Americanism is limited to research conducted about the Islamic world. However, elites in all nations compete and can trigger the traffic of opinions that they choose to polarize over.[xxii] For instance, early in Canada’s history, certain right-oriented politicians sought to exaggerate the risk of invasion by the USA to promote nationalistic feelings.[xxiii] Hence, there is no reason to dismiss the possibility that non-Muslim elites can polarize over the USA. Additionally, not all Muslim elites seek to polarize over the USA as a focal point.[xxiv] Taken together, existing studies reasonably indicate that anti-Americanism can be driven by elite polarization. However, this is not a polarization story that is peculiar to the Islamic world. Then, why do not only Muslim, but also certain non-Muslim elites choose the USA as the basis of their polarization strategy?

A candidate theory that can potentially fill in the theoretical gaps left by existing elite politics explanations of anti-Americanism is the Economic Norms Theory (ENT) by Michael Mousseau.[xxv] The ENT not only offers a generalizable explanation about elite competition over state resources, but also additionally clarifies why these elites find a strong popular basis to promote anti-Americanism. Towards that end, Mousseau counterintuitively highlights the role of economic institutions in shaping people’s values and norms.

The ENT builds on Karl Polanyi’s designation of what constitutes a market society. In his seminal book The Great Transformation, Polanyi describes the market society as a congregation of people with different kinship backgrounds that live in an urban nexus with the purpose of trading with each other.[xxvi] The institutions that guide market societies ensure the maintenance of trade flow and resultant economic profits. Accordingly, Polanyi argues that living in a market society alienates many people. Humans are not at the center of market institutions and are hence disposable if they fail to play their role in the maintenance of profit maximization. Polanyi infers that people alienated under this sense of disposability organize around counter-market movements such as Fascism, Nazism, and Communism.

Mousseau agrees with Polanyi about what constitutes a market society, yet disagrees that markets always cause alienation and dissension. Rather, market societies can engender liberal values when governed by institutions that enable strangers to trust each other in their public transactions.[xxvii] Ordinarily, it is cognitively difficult for strangers of different groups or backgrounds to trust each other in a vacuum to conduct public transactions.[xxviii] However, if a central authority can take measures to deter cheaters, strangers can start trusting each other to transact. Such measures can be in the form of public identification and/or punishment of those that violate the contracts that define the terms of economic transactions in a market system.[xxix] Accordingly, when proper contract enforcement substantially decreases the risk of cheating, market transactions occur consistently. When its transactions occur stably, a market can generate significantly greater prosperity than the more confined economic systems that we come across in non-urban settings. Ultimately, when such prosperity is attained, its participants start advocating the market system and do not mind transacting nor interacting with those whom they do not personally know.[xxx]

Many nations cannot economically afford to properly enforce the contracts that define the terms of market transactions. In such economically deficient countries, political elites are better off redistributing state rents to a small number of followers who keep them in power. This means that the rest of society remains devoid of public services, including contract enforcement, unless they constitute their leader’s winning coalition.[xxxi] Without proper contract enforcement, private citizens in the market fail to trust each other due to fear of being cheated. To minimize the risk of being cheated, people reduce the volume and frequency of market transactions with those whom they see as strangers. Then, absent contract-induced trust, market transactions, and, hence, prosperity diminish, or never accumulate in the first place. Mousseau calls these countries contract-poor nations.[xxxii]

Unlike their counterparts in contract-rich nations, the urban centers of contract-poor nations contribute little to the global economy,[xxxiii] but typically become a source of rent redistribution for political leaders to consolidate their minimum winning coalition.[xxxiv] Consequently, access to basic means of subsistence such as food, clothing, water, medicine, or electricity in urban life in contract-poor nations is not always guaranteed, but can be contingent upon loyalty to political patrons who have or who promise access to state resources. For instance, access to water in various towns in India once depended on political and ethnic affiliation.[xxxv] The urbanites who do not immediately find a patronage network risk remaining devoid of vital services. These are the urban poor. Some of the urban poor seek to solve their subsistence problems by establishing themselves in kinship networks. Yet, such networks often clash among each other and fail to generate any sufficient prosperity without any political ties.[xxxvi]

The urban poor’s material deprivation presents a major opportunity for certain political elites to exploit contract-poor nations. While the urban poor seek to find a patron that promises means of subsistence, political elites vie for de facto power, which is societal support. Without de facto power, elites’ chances of attaining de jure power remain thin in a contract-poor nation.[xxxvii] For these political elites, marketing themselves with easily comprehensible anti-market ideas can be an effective communication strategy to captivate the urban poor.[xxxviii] Moreover, research indicates that the urban poor will not be swayed by liberal and globalist values whilst facing deficiencies in material means of subsistence.[xxxix] Instead, they are more inclined to buy into any idea that targets the source of their frustration: the failed market system. To put it differently, living in an urban setting is a sign that the person in question was once captivated by the promise of prosperity from the market system. Then, material deprivation for urban dwellers represents an unfulfilled promise of the markets.[xl] Thus, political elites/patrons can target the urban poor by promoting their cause as an anti-market one. For the urban poor, the recompense for allegiance to such elites is the promise of amelioration of their means of survival in the urban environment.

As Mousseau argues, the USA is cognitively the most recognizable symbol of a modern market system in the world.[xli] Additionally, people tend to embrace easily accessible ideas with minimum cognitive effort to formulate their political opinion.[xlii] Hence, political elites in contract-poor nations can ideologically position themselves antagonistically against the USA to maximize their societal support. To the urban poor, ideological antagonism towards the USA not only reduces their cognitive dissonance compared to more inclusive ideas,[xliii] but also carries an inherent promise of salvation from supposedly market-caused poverty.[xliv] As a result, the urban poor are stuck in the traffic of anti-market and, hence, anti-American ideas, which sharpen their attitudes towards the USA.

Empirically, in contract-poor nations, urbanites who suffer from poverty may be more prone to developing a bias against the United States. Specifically, the more difficulty an urbanite faces in accessing the variety of means of subsistence (i.e., the greater the level of poverty), the more cognitive bias they are expected to form against the USA, and, hence, they express anti-American opinions as long as they live in a contract-poor nation. Accordingly, my hypothesis is stated below.

Hypothesis: the greater the level of poverty an individual suffers from, the greater the level of anti-American opinions they express if they live in an urban area and, at the same time, if they live in a contract-poor nation.

4.1. Sample

To conduct the statistical analyses, I use Pew Global Attitudes Project’s 2013 Survey.[xlv] The sample contains 31,155 observations (i.e., survey respondents) from 38 nations. In choosing the survey year, I follow three criteria: (i) being a recent survey, (ii) having a large and balanced sample of Muslim-majority and non-Muslim-majority nations, and (iii) replicability of Mousseau’s covariates of interest.[xlvi] I do not use Blaydes and Linzer’s Pew 2007, which runs into variance issues with key covariates of interest that I use to test the ENT.[xlvii] Also, though Pew 2014 and 2015 are the only two recent surveys with a larger pool of countries than 2013, only Pew 2013 has survey questions that I use to replicate Mousseau’s measurement of urban poverty.[xlviii] Overall, with these criteria, Pew 2013 stands as the optimal sample choice for the present analyses.

4.2. Anti-Americanism

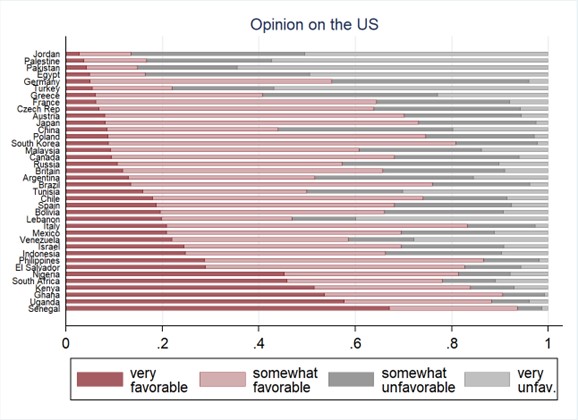

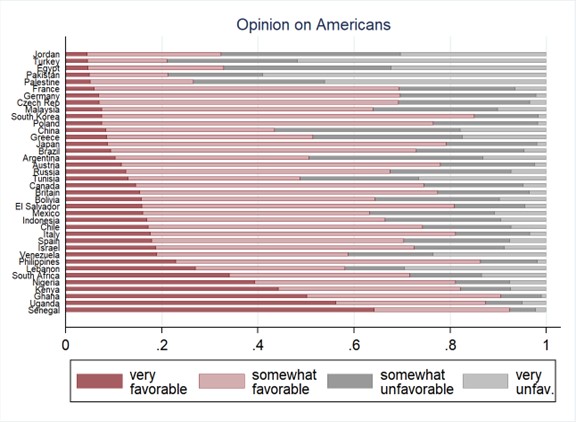

Anti-Americanism represents a negative bias in people’s evaluation of the concepts pertaining to the USA. Thus, the operationalization of anti-Americanism should consist of questions that inquire into people’s general evaluations of the USA without forcing them to articulate highly substantiated opinions.[xlix] Pew 2013 has two general-enough questions in that regard. Questions q9a and q9b ask: “Please tell me if you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of the United States/the Americans.” Figures 1A and 1B display the response distribution by country for these two questions.

Figure 1A. Response Distribution by Country in the Pew 2013 Sample (Opinion on the USA)

Figure 1B. Response Distribution by Country in the Pew 2013 Sample (Opinion on Americans)

As Figures 1A and 1B highlight, countries that have the greatest relative frequency of people who report negative opinions toward the USA also have that for Americans. In fact, negative opinions toward the USA and Americans are strongly correlated with Pearson’s r = 0.752 (p<0.001). Accordingly, instead of separately investigating the variance in both categorical variables, I sum the questions q9a and q9b.[l] Higher scores of the new continuous variable indicate greater levels of anti-Americanism.

4.3. Poverty

To measure poverty, I intend to capture the level of deficiency in a person’s basic means of subsistence. Asking about people’s income level may not always accurately reflect their lack of access to key means of subsistence. In certain countries, a person can be at a low tier of national income distribution but can also afford basic means of subsistence. Employment status tells us little about whether the person is unemployed and poor, whether they already have enough income and so do not care about joining the workforce, or whether they rely on their communities to obtain their basic means of subsistence. Finally, statements of economic satisfaction hardly capture poverty, as a survey respondent who reports dissatisfaction with their income can be a wealthy person who strives for greater income, or a poor person who is not content with their economic status. Taken together, like Mousseau, I argue that direct indicators of deficiency in material means of subsistence is the most accurate measure of poverty to assess the ENT.[li]

Accordingly, I use question q182 which asks all survey respondents: “Have there been times during the last year when you did not have enough money (a) to buy food your family needed, (b) to pay for medical and health care your family needed, and (c) to buy clothing your family needed?” For items a, b, and c, the respondents were asked to reply yes (coded as 1) or no (coded as 0). Like Mousseau, I sum the three versions of q182. Thus, if the summation takes the value of 3, this indicates that the respondent could neither afford food, medical care, nor clothing at some point one year prior to the time of the survey.[lii] The value of 0 means that the respondent had no trouble affording any of the said items of basic subsistence. In the sample, 21.17% (n=7,613) of the respondents failed to afford all three items, 9.89% (n=3,558) could not afford two of the items, and 11.89% (n=4,276) could not afford one of the items at least once in 2012. The remaining 57.05% reported not having trouble affording food, clothing, or medical care.

4.4. Urbanity

To denote whether respondents live in an urban environment or not, I rely on the country-specific versions of the question q207 of Pew 2013. For every version of this question, the surveyor records if the respondent lives in an urban, semi-urban, or rural area. Since I am only interested in marking urbanites, I create a binary variable that is recorded as 1 if the person lives in an urban area (60.09%, n=22,024), and 0 otherwise.[liii]

4.5. Contract Enforcement

I use Mousseau’s Contract Intensity of National Economies (CINE) dataset, which records the active life insurance contracts per capita for all countries in the world between 1816 and 2017.[liv] While life insurance per capita is not a direct measurement of a nation’s ability to enforce economic contracts, it indicates governments’ commitment to fulfill intergenerational contracts, which is more challenging to attain in countries with poor contract enforcement. Furthermore, most economic contracts such as rent/purchase contracts and renter’s, travel, or health insurance are binding as long as the contracting parts are alive. With life insurance, the maintenance of the contract goes beyond one’s life. The enforcement of life insurance contracts requires stronger government scrutiny than most other contracts that do not span beyond one’s lifetime.[lv] Relatedly, Mousseau’s choice of this indicator resembles a stress test for a government’s ability to monitor contracts, which makes it appropriate for the present case.

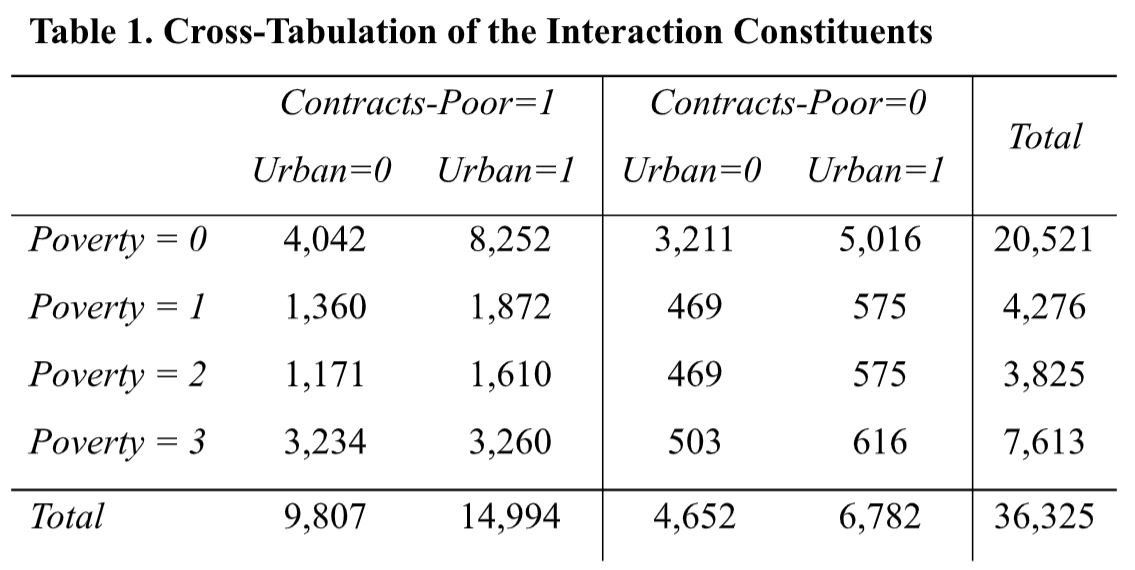

I rely on the binary version of Mousseau’s CINE score instead of the continuous version.[lvi] Specifically, this variable marks the countries that have a level of life insurance contracts per capita that is greater than the global median of the observed year. These countries are contract-intensive, whereas the rest are contract-poor countries. In the present sample, 25 countries are contract-poor (=1), but 13 are contract-intensive (=0) for the year 2012. For the interaction of contract poverty, urbanity, and poverty, Table 1 displays a cross-tabulation matrix.

4.6. Remaining Covariates

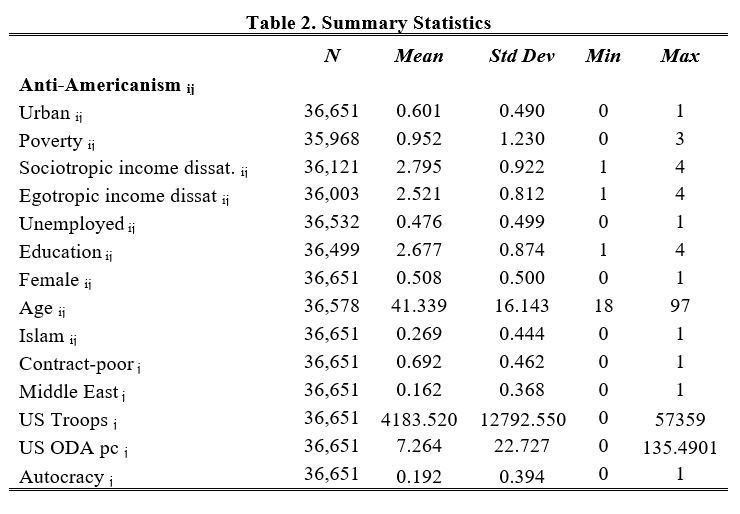

I include 10 additional covariates in the statistical models. The Online Appendix details the operationalization of these variables. First, I construct a four-item indicator recording the respondents’ dissatisfaction with their own household income. Second, I add a four-item indicator that shows the respondents’ dissatisfaction with their nation’s economic performance. Third, I create a binary variable that marks if the respondent is unemployed or not. Fourth, I create a four-category variable indicating the respondents’ educational attainment. I also include a squared term of this variable. Fifth, I record whether the respondent is female. Sixth, I control for the age of the respondent as well as its squared term. Seventh, I create a variable that is equal to 1 if the respondent follows the faith of Islam, and 0 otherwise. Eighth, I add a binary variable that is equal to 1 if the respondent is from the Middle East region, and 0 otherwise. The USA’s involvement in the Middle East can lead people in this region to be particularly anti-American. Ninth, I account for the potential confounding effect of the peaceful US troop presence in the respondents’ respective countries, as direct interaction with American troops can alleviate anti-American bias in a society. Data is borrowed from Allen et al.[lvii] Finally, Tokdemir finds that in autocratic regimes, greater US aid leads to greater frustration in the general population towards the USA, provided that this aid supplies the oppressive machinery that contributes to people’s misery.[lviii] For foreign aid, I record Official Development Assistance (ODA) data from OECD.[lix] Then I mark autocracies as countries with a Polity 2 score that is strictly less than 0.[lx] Table 2 presents the summary statistics for all the covariates that I use in the present study.[lxi]

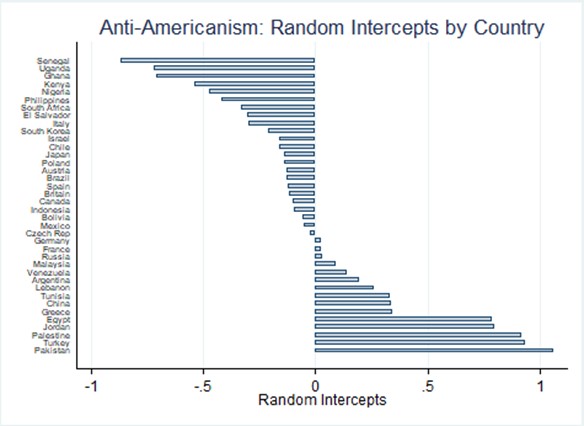

The sample is structured such that every respondent is nested within a greater unit (i.e., country). Thus, the OLS assumption regarding the independence of observations risks being violated if the individuals’ anti-American responses are related based on which country they are from. This hierarchical unit dependence problem can lead to biased estimates with OLS regression. As a remedy, I use a multilevel random intercepts modeling specification.[lxii] When I estimate this model on the outcome variable with no regressors, I observe that 26% of the variance in anti-Americanism that is explained by the statistical model is caused by country-level variances.[lxiii] This suggests that omitting the hierarchical nature of the sample risks losing a crucial level of variance in the observed outcome. Figure 2 displays the variance component estimated for each country in the sample by the ANOVA (i.e., no regressor) model.

Figure 2. Random Intercepts Distribution

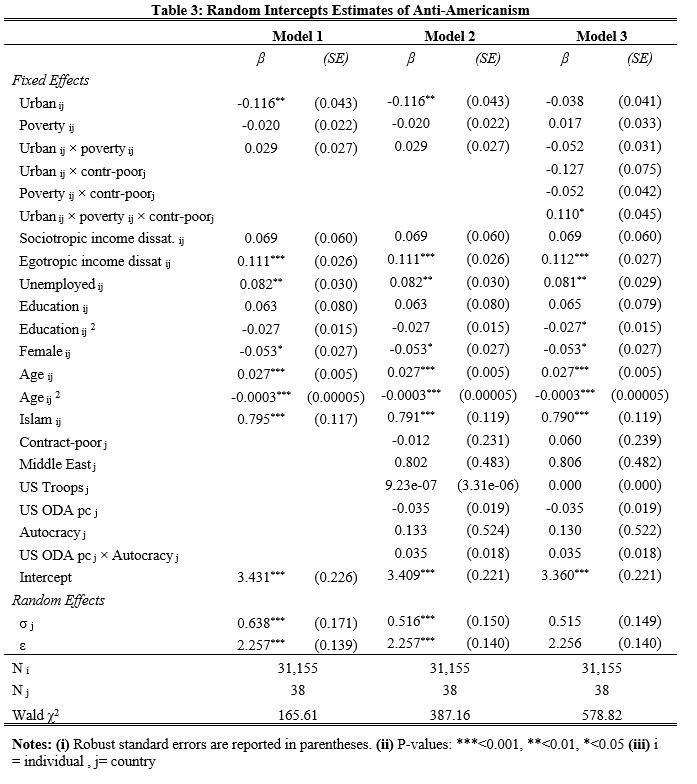

Estimates generated by the multivariate statistical models are displayed in Table 3. Model 1 in Table 3 only consists of variables that vary across survey respondents. Model 2 adds the country-level variables, which are contract poverty, Middle East region, US troop presence, and the interaction between ODA and autocracy. Finally, Model 3 displays the three-way interaction between urbanity, poverty, and contract poverty. For each model, I estimate robust standard errors and use a frequency weight relying on the relevant weighting variable presented by the Pew 2013 Survey.

Estimates from Model 1 suggest that living in an urban area has a statistically significant negative effect on anti-Americanism within a 95% confidence level (β=-0.12, p=0.006). Greater poverty, however, has a negative effect that is not statistically significant. I also include the interaction urbanij × povertyij, but I fail to observe a statistically significant effect of this interaction on the estimated outcome. This does not contradict the present hypothesis. I expect the urban-poverty interaction to increase anti-Americanism with statistical significance, only in nations with poor contract enforcement.

Model 2 adds country-level estimates to respondent-level variables. With the introduction of these variables, I observe that the variance explained by the model at the national level drops from 26 to 18.6%. However, none of the country-level variables appear to have a statistically significant effect on anti-Americanism. Moreover, contract-poor nations per se are not significantly more anti-American than contract-rich nations. Greater American troop presence does not increase or decrease anti-Americanism with statistical significance. I also find that the interaction between US ODA and autocracy has no statistically significant positive effect on Anti-Americanism. Most surprisingly, living in a Middle Eastern nation does not make respondents more anti-American than those who live in other nations.

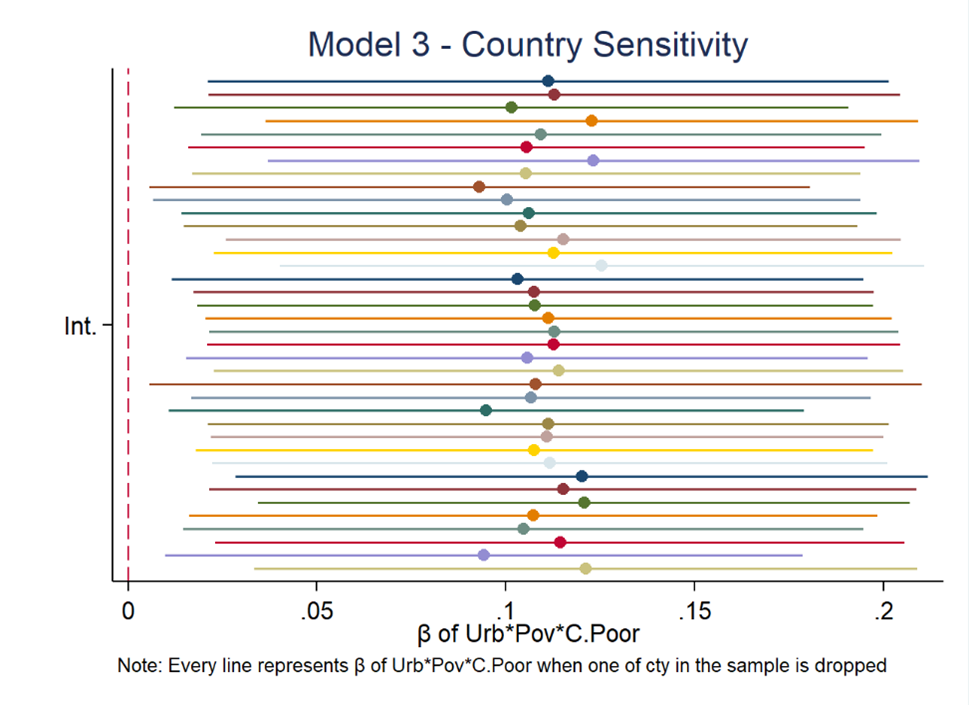

Estimates from Model 3 suggest that there potentially is statistical support for Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, holding all else constant, the β estimate for the interaction among urbanity, poverty, and contract-poverty is statistically significant (β=0.11, p=0.015). In addition, the null that all the constituents of the interaction are jointly zero can be rejected with χ2(15)=39.12 and p=0.001. I also conduct a sensitivity test and observe that the findings with regards to this interaction are not sensitive to removing any country’s observations from the sample. Figure 3 is a caterpillar plot that displays the interaction term’s 95% confidence interval values as a result of the country sensitivity test. Nevertheless, these statistics are insufficient to conclude that Hypothesis 1 finds statistical support.

Figure 3. Assessing the Country Sensitivity of the Interaction in Model 3

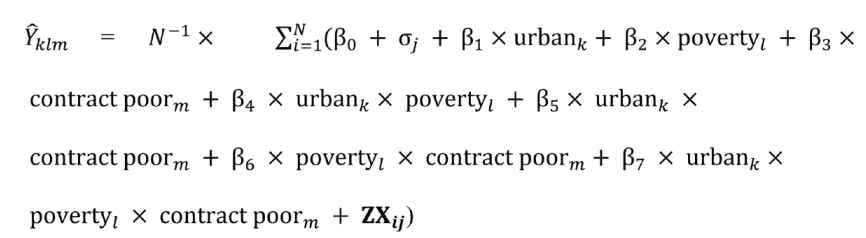

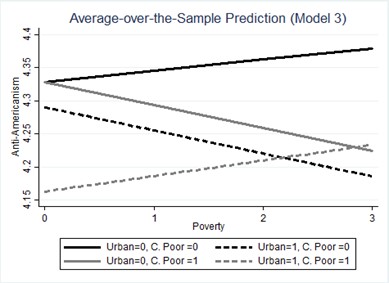

To better make sense of the three-way interaction, I first obtain the average-over-the-sample predictions of anti-Americanism scores across all simulated values of the constituents of the three-way interaction. Instead of fixing arbitrary mean and median values to the control variables, the average-over-the-sample approach only uses information from the sample. This approach gives us a clearer account of what we learn with the present modelling specification with the sample that we use.[lxiv] In doing so, for each observation in the sample, I first calculate the predicted values of anti-Americanism across each simulated value of urban k, poverty l, and contract-poor m, where k= {0, 1}, l= {0, 1, 2, 3}, m= {0, 1}. Then, for each simulated combination of k, l, and m, I sum the linear predictions of the whole sample and take the resultant average to obtain , such that:

(1)

In (1), σj represents the predicted variance component for country j, where the respondent i is from. ZXij represents the remaining covariates with their actual realization values multiplied by their impact parameters estimated in Model 3. 𝛽0 is the universal intercept estimated in Model 3. Hence, for each respondent i in country j, their individual intercept is equal to 𝛽0 + 𝜎𝑗. Figure 4 accordingly displays the predicted average-over-the-sample anti-Americanism scores for each simulated value of the constituents of the three-way interaction.[lxv]

Figure 4. Predicted Anti-Americanism by Model 3

As can be observed in Figure 4, when the contract-poor variable is simulated to be 0 (black lines), increased levels of poverty decrease anti-Americanism if urbanity is simulated to be 1 (dashed line). However, if urbanity is 0 (straight line), increased levels of poverty also increase anti-Americanism when the nation of interest is a contract-intensive one. This suggests that rural poverty is a strong driving force behind anti-Americanism in contract-intensive nations. On the other hand, when the respondent’s country is simulated to be contract-poor, we observe a pattern that is in line with ENT.[lxvi] Furthermore, in a contract-poor nation (grey lines), a respondent’s level of anti-Americanism increases if they are simulated to be an urbanite (dashed line) and decreases if they are simulated to be a non-urbanite (straight line). Stated differently, we observe that urban poverty leads to anti-Americanism if the individual lives in a contract-poor nation.

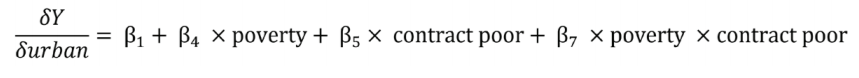

The second step in understanding the nature of the interaction involves calculating changes in the marginal effect of a constituent on the outcome variable across the simulated values of other terms in the interaction.[lxvii] In that regard, I calculate how the marginal effect of the urban variable on anti-Americanism changes across the simulated values of poverty and contract-poverty. The marginal effect of the urban variable on anti-Americanism is expressed as:

(2)

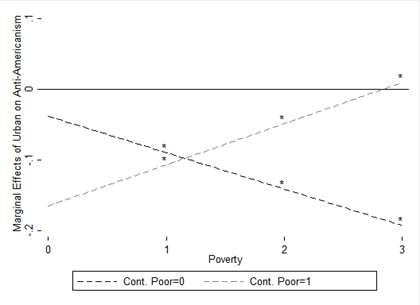

Figure 5 displays the marginal impact of the urban variable on anti-Americanism and how this impact changes due to variations in the simulated values of poverty and contract poverty. I find that urbanity’s impact on anti-Americanism becomes positive with greater values of poverty only when the respondent’s country is simulated to be a contract-poor one. On the other hand, the marginal impact of urbanity on anti-Americanism becomes more negative as poverty increases and the respondent is simulated to live in a contract-intensive country. Overall, the substantive impact of the urbanity, poverty, and contract poverty interaction on anti-Americanism appears to be in the direction suggested by ENT.[lxviii]

Figure 5. Marginal Effects Plots, Model 3 Interaction

To assess the statistical significance of the marginal effects, I estimate the standard errors for each value of the marginal effects plot obtained in Figure 5. For each marginal effect value, statistical significance fulfils the inequality , where the critical t-value is 2.1 (α=0.05) given the sample size and the degrees of freedom (15) for the interaction. The statistically significant points are marked with an asterisk above.[lxix] I find the marginal effects of poverty on urbanity across simulated values of contract poverty as statistically significant with a 95% confidence level. Details for the calculations are in the Online Appendix to conserve space in this article.

For the remainder of the covariates in Table 3, there are some intuitive and some counter-intuitive results. In terms of economic evaluation variables, while dissatisfaction with household income increases anti-Americanism with statistical significance, the same cannot be stated for dissatisfaction with national income. On the other hand, being unemployed increases anti-Americanism with statistical significance in all the models from Table 3. In terms of demographic variables, it appears that while being a female does not affect anti-Americanism with statistical significance, age does. Moreover, given that the age variable is positive with statistical significance, but its squared term is negative, there is an inverted-U type of relationship between age and anti-Americanism. I find that educational attainment has no precise effect on anti-Americanism. Finally, it was statistically significant that those who identify as Muslim score higher in anti-Americanism than those who do not. [lxx]

5.1. Robustness Checks

I conduct five robustness check operations. To save space here, I detail the results in the Online Appendix. First, albeit having a strong correlation, I estimate respondents’ attitudes towards the USA and Americans separately, using multilevel ordinal logit specification. I find that the interaction between urbanity, poverty, and countries’ contract poverty account for respondents’ somewhat and very unfavorable attitudes towards the United States as well as Americans. Thus, the ENT-driven anti-Americanism does not discriminate between the USA as a political entity and American people. It likely is a strong form of bias.

Second, to ensure that ENT-driven anti-Americanism is not sensitive to who the US president is, I investigate whether the approval of President Obama’s reelection in 2012 is driven by the interaction of urbanity, poverty, and contract poverty. I find that this is not the case, and hence ENT-driven anti-Americanism is likely impervious to the Obama effect.[lxxi]

Third, as a placebo analysis, I estimate people’s opinions towards Russia, China, and the UN as a function of the covariates specified in Table 3. I find that the ENT-driven interaction does not account for people’s opinions on Russia, China, or the UN. Thus, the ENT is likely not a mere story about nationalism, but more likely a theoretical account on how economic institutions motivate anti-modernist opinions.

Fourth, as an alternative to Mousseau’s contract poverty variable,[lxxii] I use World Bank’s Strength of Legal Rights Index measurement.[lxxiii] This indicator shows how lender and borrower rights are protected under a country’s legal system. I observe that this alternative measurement of a country’s contract enforcement capabilities still supports findings with respect to the ENT.

Finally, I retest the statistical models of Table 3 by creating a sample from the Pew 2002 Global Attitudes Survey and append it to the present Pew 2013.[lxxiv] Since Pew 2002 is the sample that Mousseau used to investigate the implications of the ENT in the case of support for suicide bombing among Muslims, a reasonable robustness check is to see if the same dataset presents evidence in favor of the present argument.[lxxv] I find that the three-way interaction between urbanity, poverty, and contract poverty increases anti-Americanism in the direction specified by the ENT with statistical significance. This finding lends additional credibility to the ENT’s ability to account for anti-Americanism.

The ENT explicates how the urban poor embrace anti-American ideas due to weak enforcement of legal contracts under a nation’s market system.[lxxvi] The statistical analyses in this paper corroborate the ENT. The greater the level of poverty an urban respondent suffers from, the more anti-American they become if they live in a contract-poor nation. This finding offers a potential answer to the question advanced in the introduction: anti-Americanization of local politics can be beneficial for elites to pursue when the central authority fails to monitor and regulate market transactions, and when there is a notably poor urban audience. This might shed light on why not only the secular opposition in Turkey but also President Erdoğan adopted anti-Americanism to vilify each other. Similarly, by Mousseau’s standards, Canada was a contract-poor nation in its earlier years. Thus, it would not be a surprise that certain politicians wanted to pursue an anti-American platform to gather support.[lxxvii]

There are two caveats to be underlined regarding the findings of the present work. First, as this paper’s statistical analyses show, the interaction among urbanity, poverty, and contract poverty does not nullify the impact of people’s affiliation with Islam. This suggests that while the ENT successfully accounts for anti-Americanism, it does not necessarily show us why Muslims, on average, are more anti-American than non-Muslims.[lxxviii] Provided that many extant studies solely focus on anti-Americanism in the Islamic world, Muslim anti-Americanism remains an under-explained and under-compared phenomenon.

Second, the outcome variable that is investigated in this paper consists of people’s general assessments of the USA and Americans. Hence, what the three-way interaction captures here is rather a level of bias and not a substantive evaluation of US foreign policy choices. The reader will be better off not employing the ENT to investigate why a random person is unhappy with, say, US involvement in Libya or Nigeria. Chances are strong that the urban poor in a contract-poor nation will be critical of US foreign policies. However, chances are also strong that those who do not suffer from poverty, who do not live in an urban area, or who live in a contract-intensive nation can still be critical of the US foreign policy agenda. Nonetheless, it is the urban poor in contract-poor nations who will be more likely than a mild critic to be dismissive about anything related to the USA and Americans, as the present analyses highlight.

There is also room for future research. Although this paper is on anti-Americanism, its implications extend beyond people’s perceptions of the USA and Americans. The Economic Norms Theory suggests that under poor enforcement of economic contracts, the urban poor will be inclined toward embracing ideas that oppose any concept related to the modern market economy.[lxxix] Accordingly, the same theory may potentially account for various issues ranging from people’s inclinations toward operating in the black market, or adherence to conspiracy theories such as so-called Zionist plans to rule the world, Bill Gates’ so-called plan to enslave humans, or opposition to IGOs such as WHO or WTO. The present findings present one of the most direct means to corroborate the ENT. Thus, future studies can move on to explore further implications of Mousseau’s theory.

Acknowledgements: This research received no funding. All errors are my own. Previous versions were presented at the ISA Northeast 2012 Conference and the Sabancı University Spring 2021 Brownbag Seminar Series. I would like to thank the conference participants as well as Mert Moral, Michael Mousseau, and Reşat Bayer for their valuable recommendations.

Data Availability Statement: In pursuit of fulfilling FAIR and Open Science principles, all data and statistical codes generated to produce this research will indefinitely be deposited in Harvard Dataverse. Readers who are interested in replicating the present results can find the replication material at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZN4WZ0

Notes

[i] Mustafa Aydın, et al., Türkiye Sosyal-Siyasal Eğilimler Araştırması 2018 (İstanbul: Kadir Has University Turkey Research Centre, 2019). https://www.khas.edu.tr/khas-kurumsal-arastirmalar/

[ii] “Pew 2013 Spring Survey Data,” Pew Research Center, March 2-May 1, 2013, accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/spring-2013-survey-data/ ; “Pew 2007 Spring Survey Data,” Pew Research Center, April 2-May 28, 2007, accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/spring-2007-survey-data/

[iii] Aydın, et al., “Türkiye Sosyal-Siyasal Eğilimler Araştırması 2018” report that around 44% of the Turks support the S-400 purchase.

[iv] Fouad Ajami, “The Falseness of Anti-Americanism,” Foreign Policy 138, (2003): 52-61; Lisa Blaydes and Drew A. Linzer, “Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism in the Islamic World,” American Political Science Review 106, no. 2 (2012): 225-243.

[v] Blaydes and Linzer, “Elite Competition,” 225-243.

[vi] Michael Mousseau, “Market Civilization and Its Clash with Terror,” International Security 27, no. 3 (2002): 5-29.

[vii] Michael A. Allen, et al., “Outside the Wire: US Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States,” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 326-341; Efe Tokdemir, “Winning Hearts & Minds (!) The Dilemma of Foreign Aid in Anti-Americanism,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 6 (2017): 819-832.

[viii] Tim Krieger and Daniel Meierrieks, “The Rise of Capitalism and the Roots of Anti-American Terrorism,” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 1 (2015): 46-61; Mousseau, “Urban Poverty and Support for Islamist Terror: Survey Results of Muslims in Fourteen Countries,” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 1 (2011): 35-47; Mousseau, “The End of War: How a Robust Marketplace and Liberal Hegemony Are Leading to Perpetual World Peace,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 160-196.

[ix] Mousseau, “Market Prosperity, Democratic Consolidation, and Democratic Peace,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44, no. 4 (2000): 472-507.

[x] Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, Anti-Americanisms in World Politics (New York: Cornell University Press, 2007).

[xi] Jinwung Kim, “Recent Anti-Americanism in South Korea: The Causes,” Asian Survey 29, no. 8 (1989): 749-763; Hamid H. Kizilbash, “Anti-Americanism in Pakistan,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 497, no. 1 (1988): 58-67.

[xii] Juan Cole, “Anti-Americanism: It’s the Policies,” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1120-1129; Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, “Friends No More? The Rise of Anti-American Nationalism in Turkey,” The Middle East Journal 64, no. 1 (2010): 51-66; Ussama Makdisi, “Anti-Americanism in the Arab World: An Interpretation of a Brief History,” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 538-557.

[xiii] Sergio Fabbrini, “Anti-Americanism and US Foreign Policy: Which Correlation?” International Politics 47, (2010): 557-573; Amaney A. Jamal, et al., “Anti-Americanism and Anti-Interventionism in Arabic Twitter Discourses,” Perspectives on Politics 13, no. 1 (2015): 55-73.

[xiv] Angus Campbell, et al., The American Voter (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960); Philip E. Converse, “Changing Conceptions of Public Opinion in the Political Process,” The Public Opinion Quarterly 51, (1987): 12-24; Benjamin I. Page, Robert Y. Shapiro, and Glenn R. Dempsey, “What Moves Public Opinion?” American Political Science Review 81, no. 1 (1987): 23-43; John R. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

[xv] Erik C. Nisbet and Teresa A. Myers, “Anti-American Sentiment as a Media Effect? Arab Media, Political Identity, and Public Opinion in the Middle East,” Communication Research 38, no. 5 (2010): 684-709.

[xvi] Ismail Onat, et al., “Framing anti-Americanism in Turkey: An Empirical Comparison of Domestic and International Media,” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 16, no. 2 (2020): 139-157.

[xvii] See, Matthew A. Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, “Media, Education and Anti-Americanism in the Muslim World,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2004): 117-133; Kim, “Recent Anti-Americanism,” 749-763.

[xviii] Blaydes and Linzer, “Elite Competition,” 225-243; Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht, “Always Blame the Americans: Anti-Americanism in Europe in the Twentieth Century,” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1067-1091; Sophie Meunier, “The Dog That Did Not Bark: Anti-Americanism and the 2008 Financial Crisis in Europe,” Review of International Political Economy 20, no. 1 (2013): 1-25.

[xix]Heiko Beyer and Ulf Liebe, “Anti-Americanism in Europe: Theoretical Mechanisms and Empirical Evidence,” European Sociological Review 30, no. 1 (2014): 90-106.

[xx] Zaller, The Nature and Origins.

[xxi] Blaydes and Linzer, “Elite Competition,” 225-243.

[xxii] James N. Druckman, Erik Peterson, and Rune Slothuus, “How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 1 (2013): 57-79.

[xxiii] Jack L. Granatstein and Reginald C. Stuart, “Yankee go Home? Canadians & Anti-Americanism,” The American Review of Canadian Studies 27, no. 2 (1997): 293-310.

[xxiv] Blaydes and Linzer, “Elite Competition,” 225-243.

[xxv] Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507.

[xxvi] Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon, 1944).

[xxvii] Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507.

[xxviii] Joshua Greene, Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap Between Us and Them (NY, New York City: Penguin Books, 2013); Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

[xxix] Paul R. Milgrom, Douglass C. North, and Barry R. Weingast, “The Role of Institutions in the Revival of Trade: The Law Merchant, Private Judges, and the Champagne Fairs,” Economics & Politics 2, no. 1 (1990): 1-23.

[xxx] Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507.

[xxxi] Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, et al., The Logic of Political Survival (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 2003).

[xxxii] Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507.

[xxxiii] Lise Bourdeau-Lepage and Jean-Marie Huriot, “Megacities without Global Functions,” Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 1, (2007): 95-114.

[xxxiv] Alberto F. Ades and Edward L. Glaeser, “Trade and Circuses: Explaining Urban Giants,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110, no. 1 (1995): 195-227.

[xxxv] Nikhil Anand, “Pressure: The Politechnics of Water supply in Mumbai,” Cultural Anthropology 26, no. 4 (2011): 542-562; Soundarya Chidambaram, “The “Right” Kind of Welfare in South India’s Urban Slums: Seva vs. Patronage and the Success of Hindu Nationalist Organizations,” Asian Survey 52, no. 2 (2012): 298-320.

[xxxvi] Matthew Desmond, “Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor,” American Journal of Sociology 117, no. 5 (2012): 1295-1335; David A. Reingold, “Social Networks and the Employment Problem of the Urban Poor,” Urban Studies 36, no. 11 (1999): 1907-1932.

[xxxvii] Daron Acemoğlu and James A. Robinson, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[xxxviii] Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[xxxix] Ronald Inglehart and Paul R. Abramson, “Economic Security and Value Change,” American Political Science Review 88, no. 2 (1994): 336-354; Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507.

[xl] Mousseau “Market Prosperity,” 472-507; “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[xli] See, Mousseau “Market Civilization,” 5-29. Also, it may be relatively more difficult to place the blame on China or Russia, neither of which are known to always advocate free market economies.

[xlii] Campbell et al., The American Voter; Zaller, The Nature and Origins.

[xliii] Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford University Press, 1957).

[xliv] Mousseau “Market Civilization” 5-29; Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[xlv] “Pew 2013 Spring Survey Data.”

[xlvi] Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[xlvii] Blaydes and Linzer “Elite Competition,” 225-243.

[xlviii] Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[xlix] Giacomo Chiozza, “Disaggregating Anti-Americanism,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds., Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, (New York: Cornell University Press, 2007), 93-126.

[l] The Pew 2013 dataset does not include more universally asked questions about the USA as q9a and q9b. Therefore, I only rely on these two questions for a combined score. If I create a factor score using Principal Component Analysis, I observe both variables to have equal weight, which is equivalent to simply summing the variables.

[li] Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[lii] Ibid.

[liii] I fail to distinguish between those who are urban, suburban, and rural due to a lack of the relevant data in the Pew 2013 survey results. Therefore, the present analyses cannot lay out a nuanced pattern with regards to types of urbanity, which would have otherwise been a relevant assessment of the ENT.

[liv] Mousseau, “The End of War,” 160-196.

[lv] Ibid.

[lvi] The binary version facilitates interpreting the three-way interaction between urbanity, poverty, and the rule of law.

[lvii] Allen, et al., “Outside the wire,” 326-341.

[lviii] Tokdemir, “Winning Hearts & Minds,” 819-832.

[lix] “Aid (ODA) Commitments to Countries and Regions [DAC3A],” OECD.Stat, December 1, 2023, accessed date December 10, 2023. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE3A

[lx] Monty G. Marshall, Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers, “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2015,” Systematic Peace, June 6, 2016, accessed date December 10, 2023. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Sophia Rabe-Hesketh and Anders Skrondal, Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling using Stata (Texas: STATA Press, 2008).

[lxiii] This is estimated as var(𝜎𝑗)/(ε+var(𝜎𝑗)) where ε is the random error component and 𝜎𝑗 is the variance of random intercepts estimated for each country j, where j={1, ..., 38}

[lxiv] Raymond M. Dutch and Randolph T. Stevenson, The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[lxv] Despite its unique strength in relying on the sample to derive information, the disadvantage of the average-over-the-sample method is the lack of clear measurement precision. Calculating standard errors for the predicted values of each row in the sample and then taking their average does not generate actual standard errors of the average-over-the-sample prediction. Thus, in the Online Appendix, I use the margins command on Stata to calculate the confidence intervals around the predicted values. I find that that the substantive impact of the interaction on the predicted anti-Americanism is weak.

[lxvi] Mousseau “Market Civilization,” 5-29.

[lxvii] Thomas Brambor, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder, “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses,” Political Analysis 14, no. 1 (2006): 63-82.

[lxviii] Mousseau “Market Civilization,” 5-29.

[lxix] Matt Golder, “Interactions,” MattGolder.com, accessed date November 10, 2023. http://mattgolder.com/interactions

[lxx] I also remove all the statistically insignificant variables from Model 3, re-estimate the model, and find that the results with regards to the three-way interaction do not change.

[lxxi] Meunier, “The Dog That Did Not Bark,” 1-25; Eike Mark Rinke, Lars Willnat, and Thorsten Quandt, “The Obama Factor: Change and Stability in Cultural and Political anti-Americanism,” International Journal of Communication 9, no. 1 (2015): 2954-2979.

[lxxii] Mousseau “The End of War,” 160-196.

[lxxiii] “The Strength of Legal Rights Index,” TheWorldBank.com, September 16, 2021, accessed date November 10, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.LGL.CRED.XQ?end=2013&start=2013

[lxxiv] “Pew Summer 2002 Survey Data,” Pew Research Center, July 2-October 31, 2002, accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/summer-2002-survey-data/

[lxxv] Mousseau “Urban Poverty,” 35-47.

[lxxvi] Mousseau “Market Civilization,” 5-29.

[lxxvii] Granatstein and Stewart “Yankee Go Home?” 293-310.

[lxxviii] Mousseau “Market Civilization,” 5-29.

[lxxix] Ibid.

Bibliography

Acemoğlu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Ades, Alberto F., and Edward L. Glaeser. “Trade and Circuses: Explaining Urban Giants.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110, no. 1 (1995): 195-227.

“Aid (ODA) Commitments to Countries and Regions [DAC3A].” OECD.Stat. December 1, 2023. Accessed date December 10, 2023. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE3A

Ajami, Fouad. “The Falseness of Anti-Americanism.” Foreign Policy 138, (2003): 52-61.

Allen, Michael A., et al. “Outside the Wire: US Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 326-341.

Anand, Nikhil. “Pressure: The Politechnics of Water supply in Mumbai.” Cultural Anthropology 26, no. 4 (2011): 542-562.

Aydın, Mustafa et al. Türkiye Sosyal-Siyasal Eğilimler Araştırması 2018. İstanbul: Kadir Has University Turkey Research Centre, 2019. https://www.khas.edu.tr/khas-kurumsal-arastirmalar/

Beyer, Heiko, and Ulf Liebe. “Anti-Americanism in Europe: Theoretical Mechanisms and Empirical Evidence.” European Sociological Review 30, no. 1 (2014): 90-106.

Blaydes, Lisa, and Drew A. Linzer. “Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism in the Islamic World.” American Political Science Review 106, no. 2 (2012): 225-243.

Bourdeau-Lepage, Lise, and Jean-Marie Huriot. “Megacities without Global Functions.” Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 1, (2007): 95-114.

Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14, no. 1 (2006): 63-82.

Campbell, Angus, et al. The American Voter. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Chidambaram, Soundarya. “The “Right” Kind of Welfare in South India’s Urban Slums: Seva vs. Patronage and the Success of Hindu Nationalist Organizations.” Asian Survey 52, no. 2 (2012): 298-320.

Chiozza, Giacomo. “Disaggregating Anti-Americanism.” In Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, 93-126. New York: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Cole, Juan. “Anti-Americanism: It’s the Policies.” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1120-1129.

Converse, Philip E. “Changing Conceptions of Public Opinion in the Political Process.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 51, (1987): 12-24.

de Mesquita, Bruce Bueno, et al. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 2003.

Desmond, Matthew. “Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor.” American Journal of Sociology 117, no. 5 (2012): 1295-1335.

Druckman, James N., Erik Peterson, and Rune Slothuus. “How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation.” American Political Science Review 107, no. 1 (2013): 57-79.

Dutch, Raymond M. and Randolph T. Stevenson. The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Fabbrini, Sergio. “Anti-Americanism and US Foreign Policy: Which Correlation?” International Politics 47, (2010): 557-573.

Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press, 1957.

Gentzkow, Matthew A., and Jesse M. Shapiro. “Media, Education and Anti-Americanism in the Muslim World.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2004): 117-133.

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E. “Always Blame the Americans: Anti-Americanism in Europe in the Twentieth Century.” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1067-1091.

Golder, Matt. “Interactions.” MattGolder.com. Accessed date November 10, 2023. http://mattgolder.com/interactions

Granatstein, Jack L., and Reginald C. Stuart. “Yankee go Home? Canadians & Anti-Americanism.” The American Review of Canadian Studies 27, no. 2 (1997): 293-310.

Greene, Joshua. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap Between Us and Them. NY, New York City: Penguin Books, 2013.

Grigoriadis, Ioannis N. “Friends No More? The Rise of Anti-American Nationalism in Turkey.” The Middle East Journal 64, no. 1 (2010): 51-66.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Paul R. Abramson. “Economic Security and Value Change.” American Political Science Review 88, no. 2 (1994): 336-354.

Jamal, Amaney A., et al. “Anti-Americanism and Anti-Interventionism in Arabic Twitter Discourses.” Perspectives on Politics 13, no. 1 (2015): 55-73.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and Robert O. Keohane, Anti-Americanisms in World Politics New York: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Kim, Jinwung. “Recent Anti-Americanism in South Korea: The Causes.” Asian Survey 29, no. 8 (1989): 749-763.

Kizilbash, Hamid H. “Anti-Americanism in Pakistan.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 497, no. 1 (1988): 58-67.

Krieger, Tim, and Daniel Meierrieks. “The Rise of Capitalism and the Roots of Anti-American Terrorism.” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 1 (2015): 46-61.

Makdisi, Ussama. “Anti-Americanism in the Arab World: An Interpretation of a Brief History,” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 538-557.

Marshall, Monty G., Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2015.” Systematic Peace. June 6, 2016. Accessed date December 10, 2023. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

Meunier, Sophie. “The Dog That Did Not Bark: Anti-Americanism and the 2008 Financial Crisis in Europe.” Review of International Political Economy 20, no. 1 (2013): 1-25.

Milgrom, Paul R., Douglass C. North, and Barry R. Weingast, “The Role of Institutions in the Revival of Trade: The Law Merchant, Private Judges, and the Champagne Fairs,” Economics & Politics 2, no. 1 (1990): 1-23.

Mousseau, Michael. “Market Civilization and Its Clash with Terror.” International Security 27, no. 3 (2002): 5-29.

——. “Market Prosperity, Democratic Consolidation, and Democratic Peace,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44, no. 4 (2000): 472-507.

——. “The End of War: How a Robust Marketplace and Liberal Hegemony Are Leading to Perpetual World Peace,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 160-196.

——. “Urban Poverty and Support for Islamist Terror: Survey Results of Muslims in Fourteen Countries,” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 1 (2011): 35-47.

Nisbet, Erik C., and Teresa A. Myers. “Anti-American Sentiment as a Media Effect? Arab Media, Political Identity, and Public Opinion in the Middle East.” Communication Research 38, no. 5 (2010): 684-709.

Onat, Ismail, et al. “Framing anti-Americanism in Turkey: An Empirical Comparison of Domestic and International Media.” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 16, no. 2 (2020): 139-157.

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Page, Benjamin I., Robert Y. Shapiro, and Glenn R. Dempsey. “What Moves Public Opinion?” American Political Science Review 81, no. 1 (1987): 23-43.

“Pew 2007 Spring Survey Data.” Pew Research Center. April 2-May 28, 2007. Accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/spring-2007-survey-data/

“Pew 2013 Spring Survey Data.” Pew Research Center. March 2-May 1, 2013. Accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/spring-2013-survey-data/

“Pew Summer 2002 Survey Data.” Pew Research Center. July 2-October 31, 2002. Accessed date November 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/dataset/summer-2002-survey-data/

Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon, 1944.

Rabe-Hesketh, Sophia, and Anders Skrondal. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling using Stata. Texas: STATA Press, 2008.

Reingold, David A. “Social Networks and the Employment Problem of the Urban Poor.” Urban Studies 36, no. 11 (1999): 1907-1932.

Rinke, Eike Mark, Lars Willnat, and Thorsten Quandt. “The Obama Factor: Change and Stability in Cultural and Political anti-Americanism.” International Journal of Communication 9, no. 1 (2015): 2954-2979.

“The Strength of Legal Rights Index.” TheWorldBank.com. September 16, 2021. Accessed date November 10, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.LGL.CRED.XQ?end=2013&start=2013

Tokdemir, Efe. “Winning Hearts & Minds (!) The Dilemma of Foreign Aid in Anti-Americanism.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 6 (2017): 819-832.

Zaller, John R. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992.