Zuhal Çalık Topuz, Ardahan University

Jonathan Michael Spector, University of North Texas

Abstract

Interest similarity is defined as the affinity of national interests in global affairs. This research aims to examine the interest similarity among Turkey, Israel, and the US. Interest similarity of countries has been examined by taking into account the factors of (a) alliance portfolio, (b) MID data, and (c) UNGA voting records. Quantitative data regarding these factors have been analyzed with correlation and regression models. The findings show that the interest similarities among these three countries have a statistically significant correlation. This research also examines the relationships between the three states to better understand which factors affect their interest similarity, and how. Thus, this study contributes to the political science and international relations literature by analyzing quantitative data while examining the interest similarity among Turkey, Israel, and the US.

In the International Relations (IR) literature, “bilateral political relationships have been characterized by the degree of similarity of national interests in global affairs between countries.”[1] In this respect, interest similarity helps researchers to characterize the foreign policies of states in terms of their powers, interests, preferences, and perceptions. Gartzke proposes measuring states’ national interests through their preferences.[2] “Preferences and interests play a crucial role in many IR theories, but they are difficult to operationalize.”[3] Since it is difficult to observe the attitudes/preferences of states directly in foreign policy, it is necessary to obtain observable data showing these attitudes. Accordingly, this study has calculated “interest similarity scores” to evaluate political similarity among Turkey, Israel, and the US.

Since the relations and interests of Turkey, Israel, and the US converge on the Middle East region, there are several reasons that make it important to examine the interest similarity among these three countries. Concerning the triangular relationship among Turkey, Israel, and the US, some observers have suggested that “there appeared to be a natural convergence of interests.”[4] Turkey and Israel are two regional powers that share many similarities in their strategic outlooks. At the global level, the two states have displayed a strong pro-American orientation in their foreign policy.[5] The stability of Turkish-Israeli relations holds great importance for the United States, “which is allied to both countries and has long viewed the Turkish-Israeli friendship as one of the most important components of its policies in the Middle East region.”[6] Therefore, US leadership has also played a central role in shaping—and often mediating—the Turkish-Israeli relationship.[7] While the relationship between Turkey and Israel provides military, economic, and diplomatic benefits to both countries, the close coordination between the two countries also provides an advantage for the interests of the US in the Middle East region.[8] In this context, it is important to examine the similarity of national interests of these three allies in terms of adding a different dimension to the literature.

The intersection of their interests is an important factor in the formation of a strong association among the three countries.[9] Internal and external factors affecting the relations between the three countries (for instance, Middle East political dynamics, security and economic concerns, and the structure of the international system) have been effective in establishing a strong diplomatic association among them. In the pre- and post-Cold War periods, tripartite relations mainly included policy harmony. Therefore, relations between these three countries whose interests intersect have gradually evolved into strategic relations.[10] However, these trilateral relations have become a bottleneck during the period of 2008-2021. International and regional conjunctural changes contributed to the deterioration of relations, given that “as Turkey’s domestic power structure changed, so too did its foreign alignment choices.”[11] Therefore, Turkey’s national interests were not fully compatible with the interests of both the US and Israel in this period.[12] The Turkey-Israel part of the triangle has had problems since 2010. Turkey-Israel relations, which had the greatest tension given the Mavi Marmara incident (May 2010), affected Turkey’s relations with the United States.[13] As a result of this high tension, the US, together with Israel, voted “No” against Turkey in the UN Human Rights Council (A/HRC/15/21, 2010). Also, in the same period (June 2010), Turkey’s decision to vote “No” against the sanctions on Iranian nuclear power at the UN Security Council showed a difference of interests between the United States and Israel and reflected Turkey’s attitude towards these two countries. Both of these events made it clear to the three states that there were serious differences in their approaches to and interests in regional issues. “Turkey has been critical of the US failure to put greater pressure on Israel, while the United States has been uncomfortable with the extent of Turkey’s continued dealings with Iran.”[14] Moreover, the geopolitical changes experienced during the Arab Spring caused a change in the Middle East in the 2010s and also affected relations among Turkey, Israel,[15] and the US. These types of events create a new dynamic and also provide evidence that bilateral relationships can affect tripartite relationships. The literature shows that as the interests of states intersect, their relations improve, and as the interests of states differ with the effects of local, regional, and global developments, their relations become strained.[16] As a recent example, the visit of Israel’s President to Turkey in February 2022 was expressed as the beginning of a new turning point in bilateral relations.[17] Future relations among Turkey, Israel, and the United States may also be affected by other new developments currently being initiated in the international arena,[18] such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the future role of NATO. Time will tell if this step taken to improve relations between Turkey and Israel will be reflected in Turkey-USA and Israel-USA relations.

Many leading theories in the field of international relations emphasize the significance of interest similarity as a key determinant of conflict and cooperation between countries.[19] Interest similarity includes data that are employed to evaluate the interests or opposing interests of state pairs. The degree of similar or opposite interests, obtained by looking at the relationship between MID, alliance, and UNGA votes data, gives us concrete data on cooperation and conflict in interstate relations.[20] The measure of interest similarity matches up well with significant periods of both cooperation and conflict. Thus, the three states’ interest similarity was measured with (1) alliance portfolio, (2) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID)[21] data, and (3) the similarity of votes in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA).

These three indicators, which were used to demonstrate the interests of states, will be ideal for quantitatively testing the preferences of the states in their national policies. Alliance portfolios were accepted as one of the central tools in which states build up their relations and behaviors in the international system[22] and were also used as the indicator of national preferences of states.[23] In this respect, alliance portfolios were an indicator in determining the similarity or diversity of common interests between states.[24] According to Bueno de Mesquita, the similarity of nations’ respective alliance portfolios is a measure of the similarity or commonality of those nations’ underlying security interests.[25] Various data analyses were conducted on how the interactions of states would end and why conflicts began. Causal models have been developed to make sense of the behavior of states for this purpose. The most widely used measurement of analysis in interstate conflicts is the Interstate Militarized Dispute (MID) dataset.[26] Although MID refers to a clear threat of sovereign states’ desire to use military power,[27] it is defined as a situation stemming from the interactions that resulted in peace or conflict between states.[28] MID portfolios enable our operationalization of common interests to tap both the cooperation and conflictual aspects of revealed preferences.[29] The most costly signal a state can send about its preferences is to engage in war with another state.[30] The least significant indicator is each state’s United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting record. The decisions made at the UNGA provide a setting in which states express their positions and interests in the global order, even if these decisions are not binding. “These similarity measures are all predicated on the idea that observing a pair of states voting frequently in unison is the result of preference affinities.”[31] In various studies, voting behavior in international organizations, especially the UNGA, is used to reveal the similarity of member countries’ foreign policy preferences.[32] As Voeten notes about the UNGA voting records, “there is no obvious other source of data where so many states over such a long time period have revealed policy positions on such a wide set of issues.”[33] Thus, states’ voting preferences at the UNGA provide information about their unique policy preferences.[34] On the other hand, voting preferences may not always reflect the foreign policy of a state since voting choices depend on the strategic agenda of states and can be affected by pressure from key global and regional actors.[35] Even if the countries cannot fully reflect their preferences in the UN Security Council due to the binding nature of the Security Council, they often vote reflecting their own views in the UNGA.[36]

There are various studies in the extant literature in which interest similarity is used to evaluate states’ preferences. For example, the study conducted by Sweeney uses a similar interest construct to measure cooperation and conflicts of interest among the United States-Russia/Soviet Union, France-Germany/West Germany, Israel-Egypt, and Israel-Syria.[37] Furthermore, Strüver uses UNGA voting data to assess the foreign policy similarity of China.[38] Strüver’s analysis involves studying voting patterns and behavior in the UNGA over the past two decades to understand why countries tend to vote similarly on various foreign policy issues. Johnston, meanwhile, shows the preferences and interests of China’s conflict behavior and crisis management by using MID data.[39] Finally, Rajapakshe examines the similarity of interests and related effects in bilateral relations between states based on China-Sri Lanka relations.[40] He investigates China’s credibility in explaining the similarities of its interests with other countries, particularly in the context of economic, diplomatic, strategic, and military relations, as well as bilateral relations. The outcomes of the study demonstrate that China’s ability to foster similarity of interests appears to stem from its effective engagement with smaller states in international politics. Thus, interest similarity can help to measure states’ preferences with analysis of the alliance, MID data, and UNGA voting records under changing domestic, regional, and international circumstances.

Consequently, this research aims to examine whether the bilateral political similarity between Turkey, Israel, and the US is statistically related to interest similarity, and to reveal the effects of interest similarity among Turkey, Israel, and the US on relations among these countries. For these purposes, three data sources (alliance, MID, and UNGA voting records) were used to reveal these countries’ interests. This study explores trilateral interest similarity as its primary focus, with the example of Israel, Turkey, and the US serving as an illustration. It also employs quantitative methods to analyze the trilateral similarity of interests among Israel, Turkey, and the United States. The research questions guiding the study are listed as follows:

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Firstly, Section 2 explains the theoretical issues of the concepts of national interest and interest similarity. Then, Section 3 elaborates on data selection, collection, and analysis. Thereafter, Section 4 presents the results and discusses them via existing literature. Finally, Section 5 concludes the research by stressing various issues that need further research.

The interests of states are frequently used in the foreign policy analysis of states, as they are an important explanatory tool in international politics. Since the interests of states are not directly observable, the theoretical literature on interests reveals the meaning and origin of this issue. Examining the interests of states from different theoretical perspectives helps to understand the importance that states attach to their national interests. The national interest, which is used in explaining the interest similarity of states, is theoretically discussed in this section, and the views of different theories on the national interest concept is evaluated.

The concept of national interest is at the center of some international relations theories because of its role in explaining the behavior of states.[41] Per IR theories, a state’s foreign policy reflects its national interests, and thus, the national interests of the state are good variables for foreign policy. Therefore, a theoretical discussion could offer useful explanations of national interests. The concept of national interest has been examined through the lenses of realism, liberalism, constructivism, and many other theories of international relations. The perspectives of these theories regarding national interest are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: The Theoretical Toolbox

| International Relations Theory | National Interest |

| Realism | National interest defined as the

security and survival of the state |

| Neo-Realism | National interest is a product of the structure of the international system |

| Liberalism | Interests are an important determinant of conflict severity |

| Neo-Liberalism | National interest should be focused on the pursuit of peace among nations. |

| Constructivism | National interests constituted by ideas and identities |

The realist approach infers that states act in line with their national interests in their foreign policies, asserting that it should be “the one guiding star, one standard thought, one rule of action” in foreign policy.[42] For this reason, Realists expect the most violent interstate conflicts to occur between states with different policy interests. Liberals, on the other hand, see interests as an important determinant in the initiation and escalation of conflict. In terms of constructivism, national interest is a social construction and, at the same time, an important explanatory tool in international politics.

Each theory presents a different take on national interests. From a theoretical point of view, national interest has theoretical and empirical strengths and weaknesses. But they all argue that states with similar values or interests will establish a close relationship with shared interests, and that “the degree of interest similarity is an important determinant of dyadic conflict and cooperation.”[43] For example, while Turkey-US relations moved to the dimension of strategic partnership in the 1990s, they were strained in the 2000s when the USA’s request to open a front to northern Iraq through Turkey was rejected. The national interests of countries may change, or the conflicting interests of today may turn into complementary interests for tomorrow.

Consequently, foreign policies of states are driven by their national interests, and the pursuit of national interests is the objective of a state’s foreign policy.[44] National interests offer a very appropriate framework to the international relations literature for the systematic examination of relations between states. Therefore, a theoretical discussion of this research has been formed within the framework of national interests. While accepting that national interests have different dimensions, this research has tried to present a concrete framework by emphasizing the importance of three different data in the analysis of state interests, namely: alliance, MID, and UNGA votes. By analyzing these data, the research aims to reveal the interest similarity of Turkey, Israel, and the US to each other through their national interests.

This section identifies how the research is designed in order to answer the research questions in terms of the (1) data analysis method, (2) data selection and collection process, (3) data analysis process, and (4) limitations of the study.

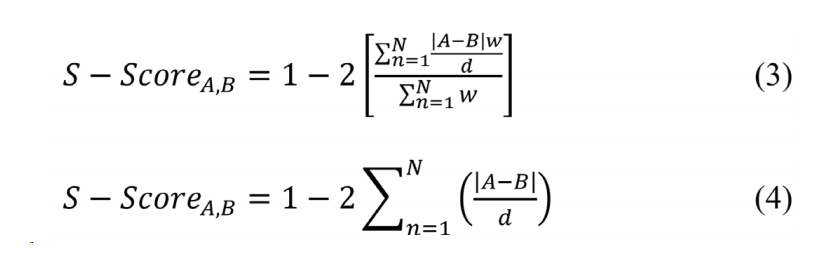

To evaluate the interest similarity,[45] we calculated the S-Score (Spatial Score) proposed by Signorino and Ritter. Signorino and Ritter have expressed that “…the closer two states are in the policy space - i.e. the closer their revealed policy positions - the more ‘similar’ their revealed policy positions. The further apart two states are in the policy space, the more dissimilar their revealed policy preferences.”[46] Thus, S has become something of a standard measure in the field of quantitative studies of international relations.[47] In this way, the qualitative data (i.e., existence of war or alliance, and foreign policy preferences) are converted into quantitative data (such as 0 or 1) in the evaluation of relations between countries, and the evaluation is made with the S-Score.[48] Bapat expressed that “Signorino and Ritter’s weighted measure of S captures the political similarity between target and host states.”[49] The interest similarity score takes a value between -1 and +1, and the proximity of this value to -1 shows a non-compliant relation while +1 shows a compliant relation.

Since political affinities among Turkey, Israel, and the US would be examined based on interest similarity score, the following data were selected to calculate S-Score: (1) Alliance,[50] (2) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID),[51] and (3) UNGA votes.[52] In addition, considering the US is dominant/hegemonic in all dyads, the “weighted S-Score” method is used in order to calculate the interest similarity score through alliance and MID data. Therefore, (4) CINC (The Composite Index of National Capability)[53] data of each country were selected as the weight value in the weighted S-Score calculation. Thus, Appendix 1 shows all selected factors included in this research in order to calculate the S-Score.

To collect data regarding alliance, MID, CINC, and UNGA votes, we used two open-source dataset libraries. Firstly, alliance, MID, and CINC data were collected from “The Correlates of War Project.”[54] Secondly, UNGA vote data were collected from the “United Nations General Assembly Voting Data.”[55] Then, we calculated the S-Score using these four types of collected data. Thus, a total number of 72 dyadic data were used for the period of 1948-2019. The following subsection explains how we calculated the S-Score and how the similarity of interests can be interpreted based on the S-Score.

To obtain S-Scores between each pair of countries (S-ScoreIsrael-Turkey, S-ScoreIsrael-US, and S-ScoreTurkey-US), we have calculated (i) S-ScoreAlliance, (ii) S-ScoreMID, and (iii) S-ScoreUNGA_Votes for each pair of countries. Then, by taking the average of these S-Scores, we obtained the S-Score values between each pair of countries. For instance, S-ScoreTurkey-Israel = [S-ScoreAlliance (TUR_ISR) + S-ScoreMID (TUR_ISR) + S-ScoreUNGA_Votes (TUR_ISR)] / 3.

Firstly, to calculate S-ScoreAlliance, we have taken into account each alliance between the two countries. The alliance value in the dataset refers to one of the four alternative scores: 3 refers to Defense Pact, 2 refers to Neutrality or Non-Aggression Pact, 1 refers to Entente, and 0 refers to No Alliance. The Defense Pact entails military alliances to support treaty partners in any military interventions. The Neutrality or Non-Aggression Pact is a promise between signatories to remain military-neutral. Finally, Entente is an arrangement between nations to follow a particular policy in a crisis.[56]

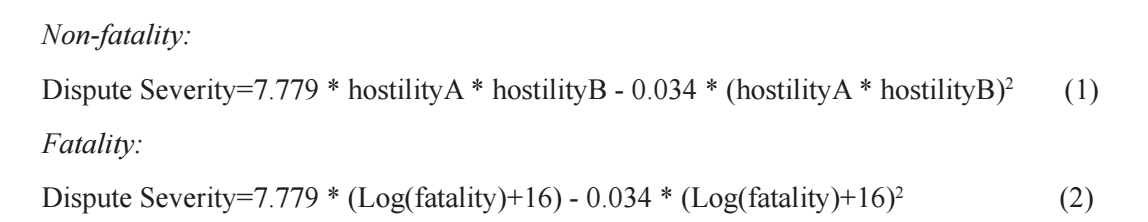

Secondly, to calculate S-ScoreMID between two countries, the fatality value is taken into account, and one of two different formulas is used based on this value because the probability of death in a conflict between two countries is interpreted differently in terms of the severity of the conflict.[57] Hostility level consists of a score between 1 and 4. 1 refers to no military action, 2 refers to a threat to use military force, 3 refers to a display of military force, and 4 refers to the actual use of force. To express the fatality level of the conflict, a score between 0 and 6 is listed according to the death toll of the created groups. Fatality level is categorized as follows in the MID data set: (1) 0, (2) 1-25, (3) 26-100, (4) 101-250, (5) 251-500, and (6) 501-999. In this context, the BRL (Baseline Rivalry Level) scale, which was developed by Diehl and Goertz, was used in processing the hostility and fatality level data. If there are no deaths when calculating the BRL score from the MID data, the hostility level of country A and B is used; however, if there is death, the fatality level is used. The formula used in calculating the BRL scale is presented in Equations 1 and 2 below.[58]

Thirdly, to calculate S-ScoreUNGA_Votes, three alternative values are used in the calculation of the S-Score from the UNGA votes of the countries in question. Among these values, 1 refers to Yes, 2 refers to Abstain, and 3 refers to No.[59]

The CINC score was used as the weight value in the weight calculation of the S-Score, which is among Alliance and MID data. CINC is a generally used measure of national power in the field of international relations.[60] The CINC score constitutes a combination in the calculation of national power by using demographic, economic, and military components.

Several criteria have been taken into account in the calculation of the binary alliance, MID, and UN Voting S-Score points of the three countries. These criteria are given in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Criteria Taken into Account in S-Score Calculation

| Alliance | MID | UN Voting |

| The data of all countries were taken into account because if the countries that do not have an agreement are similar, this affects the score. | Only the data that included two countries in conflict or at war were included in the calculation. | If one country voted for a resolution and the other did not, that decision was not taken. |

| Since some countries did not have CINC data for some years, in such cases, the CINC data were obtained from the CINC data average of the year before and after the corresponding year. | Since some countries did not have CINC data for some years, in such cases, the CINC data were obtained from the CINC data average of the year before and after the corresponding year. | CINC data were not used since UNGA Voting score calculation was made unweighted. |

| If there was more than one datum in a year between the two countries, only the wide-range alliance datum was included in the calculation of the alliance score. | If there was more than one datum in a year between the two countries, only the datum with higher value was included in the calculation of the MID score. | There was no resolution that Israel joined in 1948. In 1964, no country had United Nations resolutions. |

| When calculating on a yearly basis, the highest alliance value of that year was used in the crossover, with each country corresponding to its own name. | The level of conflict in the matrix of the country of the same name was set to zero (0) in the calculation process. |

By considering the criteria given in Table 2, Equation-3 was used for alliance and MID, and Equation-4 was used for UN voting in the calculation of S-Score values.

In equations 3 and 4, N refers to the total number of data, A refers to a datum of one of the countries, B refers to the datum of the other country, w refers to the weight score of the country, and d refers to the difference between A and B. Interest Similarity is the average of the S-Scores for weighted MID portfolios, weighted alliance portfolios, and unweighted UN General Assembly voting portfolios. This study differs from the studies in which the weights of the countries are considered equal in the literature, because it uses the CINC values as the weight value of countries in S-Score calculation.

To analyze the data, R Project and SPSS 25 were used as data analyzing tools. R Project software was used in order to calculate the S-Score with alliance, MID, UNGA voting, and CINC data. These calculated S-Score values were used with SPSS 25 software for correlation analysis and a regression model. The correlation analysis explained whether the bilateral relations between the countries were statistically significant, and the regression model explained the factors that affected the bilateral relations. In addition, in order to determine the suitable correlation analysis method (e.g., Pearson, Spearman), it was taken into account whether data are distributed normally or not. Thus, correlation analysis was carried out by using the two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficient method.

The beginning period of this research was determined as 1948 since Israel was established in that year. Additionally, the end period of this research was determined as 2019 since UNGA voting data were limited to the period of 1946-2019. Furthermore, alliance data is limited to the period of 1816-2012, and MID data is limited to the period of 1816-2010.

This section includes an assessment of the political affinities between Turkey, Israel, and the United States for the period 1948-2019 based on the results of correlation and regression analysis to reveal the impact of bilateral relationships. Quantitative findings regarding the correlation and regression analysis results are presented first, and then the results are discussed from the aspect of each country considering both the quantitative findings and the existing literature.

The first research question examines the existence of statistically significant correlations between bilateral relationships among Turkey, Israel, and the US. Correlation analysis results have been presented from the aspect of (1) Turkey, (2) Israel, and (3) the US, respectively.

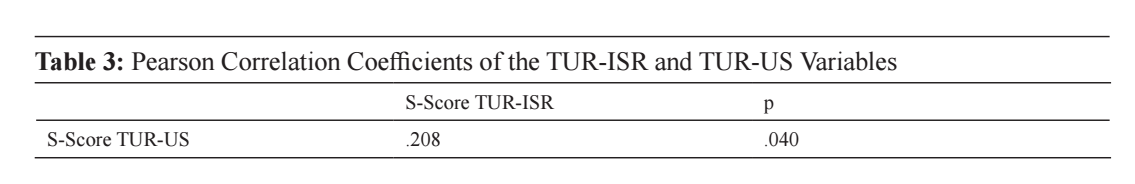

Firstly, the bilateral relationships were examined from the aspect of Turkey, and Table 3 shows the correlation analysis results that reveal whether there is a statistically significant correlation between Turkey-US and Turkey-Israel relationships in terms of interest similarity.

According to Table 3, there is a statistically significant (P<.05) and weak-positive correlation (.208) between the interest similarities of Turkey-US and Turkey-Israel. How can this statistically significant correlation/result contribute to the discipline of Political Science? This correlation proved, based on quantitative data, that Turkey’s political similarity towards Israel was associated with Turkey’s political similarity towards the United States during the period of 1948-2019. This correlation of political similarity can also be expressed as follows: when the level of interest similarity between Turkey and Israel increased or decreased, then the level of interest similarity between Turkey and the USA similarly increased or decreased.

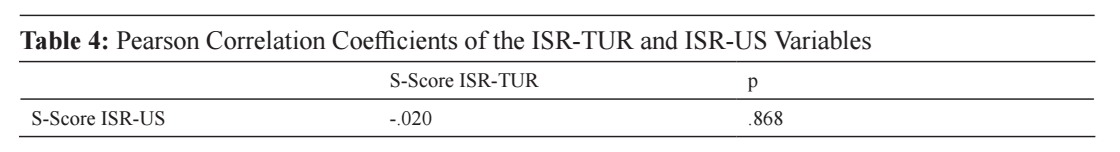

Table 4 shows the results of the correlation analysis in terms of Israel and helps us to understand whether there is a statistically significant correlation between the Israel-Turkey and the Israel-US interest similarities.

Table 4 shows that there is no statistically significant (P>.05) correlation between the interest similarities of Israel-Turkey and Israel-US. Accordingly, this absence of correlation of political similarity can be expressed as follows: the interest similarity between Israel and the US is not correlated with the interest similarity between Israel and Turkey for the period of 1949-2019.

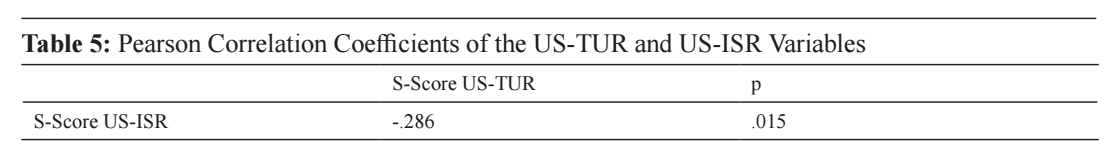

The presence of a significant correlation is also questioned in terms of the US, and Table 5 shows the results regarding whether there is a statistically significant correlation between the US-Turkey and the US-Israel relationships in terms of interest similarity.

Table 5 shows that there is a statistically significant (P<.05) and weak-negative correlation (-.286) between the US-Turkey and the US-Israel relationships. Accordingly, this correlation of political similarity can be expressed as follows: during the period of 1948-2019, when the interest similarity between the US and Turkey increased, then the interest similarity between the US and Israel decreased, and when interest similarity between the US and Israel increased, then the interest similarity between the US and Turkey decreased.

Upon understanding that there are statistically significant correlations among the bilateral relationships in terms of interest similarity, a regression analysis was performed in order to determine the factors affecting the relationships with the third remaining country, and the results are presented below.

The second research question defines the interest similarity factors affecting the bilateral relationships and determines the direction of effects in such relationships among Turkey, Israel, and the US. Thus, a regression model was employed to examine the relationships, and the analysis results have been presented and discussed from the aspect of (1) the Turkey-Israel relationship, (2) the Turkey-US relationship, and (3) the US-Israel relationship, respectively.

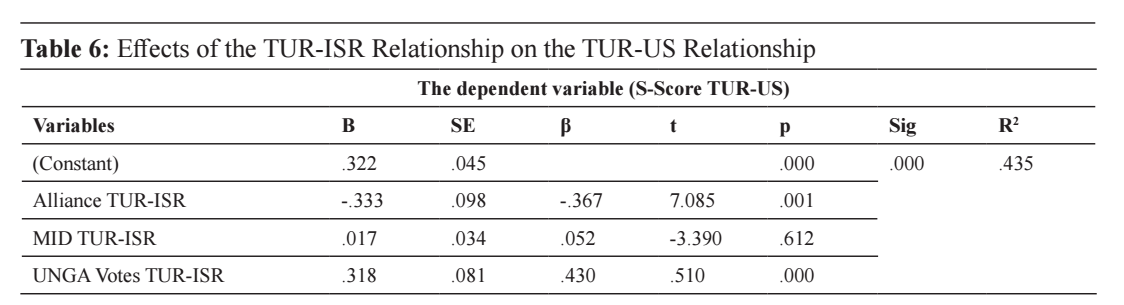

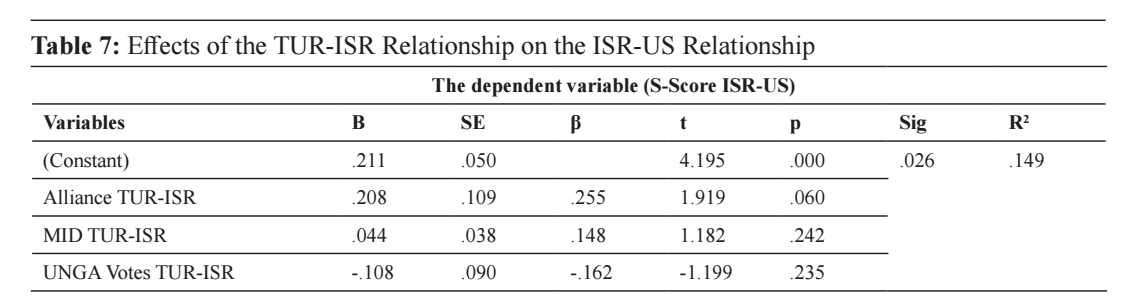

The regression analysis results regarding the effects of interest similarity between Turkey and Israel on the interest similarities between Turkey-US and Israel-US are shown in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively.

Table 6 shows that 43.5% of the interest similarity between Turkey and the US can be explained by the interest similarity between Turkey and Israel. In other words, the interest similarity of the Turkey-Israel relationship affects the Turkey-US relationship at a rate of 43.5%. It was found that similarity in UNGA votes between Turkey and Israel has a powerful effect on the Turkey-US relationship in terms of political similarity (see the UNGA votes graphic in Appendix 2). Therefore, the political similarity of UNGA votes between Turkey and Israel may have reflected the relations between Turkey and the US in the past, or it might positively affect Turkey-US relations in the future. Furthermore, it was found that political similarity between Turkey and Israel in terms of military disputes has no impact on the Turkey-US relationship in terms of interest similarity (see the MID data graphic in Appendix 3). Moreover, the political similarity between Turkey and Israel in terms of alliance portfolio has a negative impact on the Turkey-US relationship in terms of interest similarity (see the alliance data graphic in Appendix 4).

Table 7 shows that 14.9% of the interest similarity between Israel and the US can be explained by the Israel-Turkey relationship in terms of interest similarity. In other words, the interest similarity of the Israel-Turkey relationship affects the interest similarity of the Israel-US relationship at a rate of 14.9%. Additionally, political similarity between Israel and Turkey in terms of alliance portfolio has a positive impact on the interest similarity of Israel and the US. Thus, as the level of similarity in the alliance portfolio between Israel and Turkey has increased, the level of interest similarity in the Israel-US relationship has also increased. On the other hand, when Israel strengthened its alliance with Turkey, political similarity between Israel and the US also increased, or the interest similarity between Israel and the US may have led Israel to strengthen its alliance with Turkey. Since political similarity in the Turkey-Israel relationship is important for the protection of the US’s interests in the Middle East, the impact of the Israel-Turkey relationship on the Israel-US relationship can be explained from this perspective.

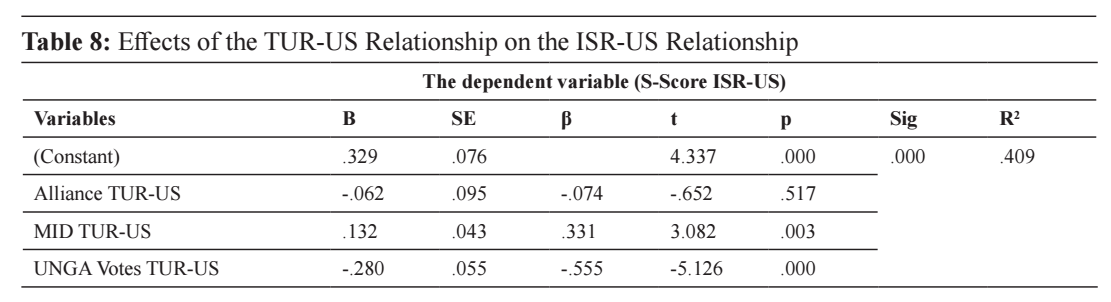

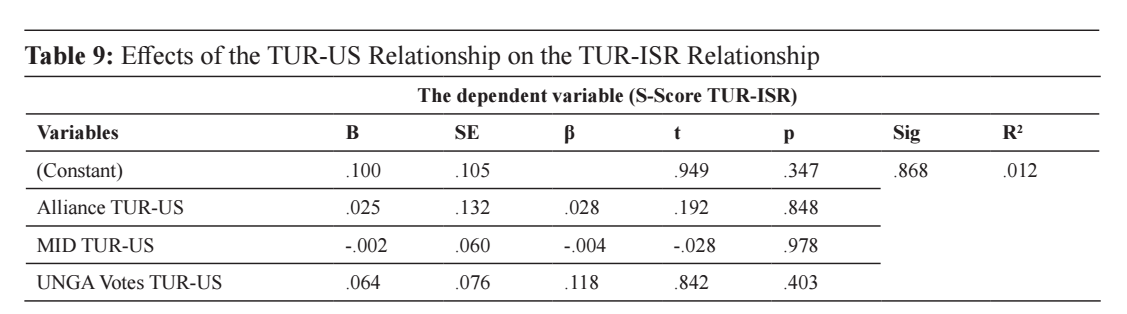

The regression analysis results regarding the effects of the interest similarity between Turkey and the US on the interest similarities of Israel-Turkey and Israel-US were shown in Table 8 and Table 9, respectively.

Table 8 shows that 40.9% of the interest similarity between the US and Israel can be explained by the interest similarity between the US and Turkey. In other words, the interest similarity of the US-Turkey relationship affects the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship at a rate of 40.9%. Furthermore, it was found that political similarity between the US and Turkey in terms of both military disputes and UNGA votes has an impact on the US-Israel relationship in terms of interest similarity. Thus, the US may have considered its interest similarity with Turkey in determining its interest similarity with Israel. However, interestingly, although political similarity between the US and Turkey in terms of military disputes positively affected the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship, the similarity of UNGA votes between the US and Turkey negatively affected the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship. At this point, future studies can analyze UNGA votes to understand which kind of decisions caused this negative effect.

Table 9 shows that the effect of the Turkey-US relationship on the Turkey-Israel relationship was not at a statistically significant level (P>.05). In other words, Turkey’s relationship with Israel was not affected by Turkey’s relationship with the US. The Interest Similarity Graphic presented in Appendix 5 shows that the relationship between Turkey and Israel has an up-and-down trend in some periods; however, in these periods, the Turkey-US relationship was stable and not affected by this fluctuation. For this reason, the inability to explain the change in the Turkey-Israel relationship given the Turkey-US relationship is an understandable result.

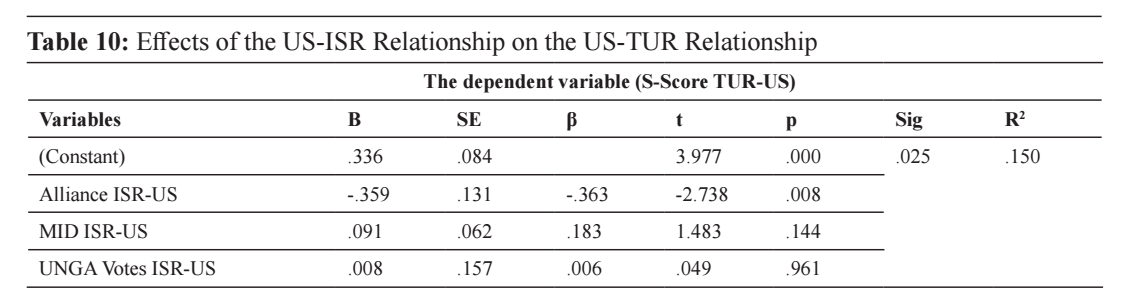

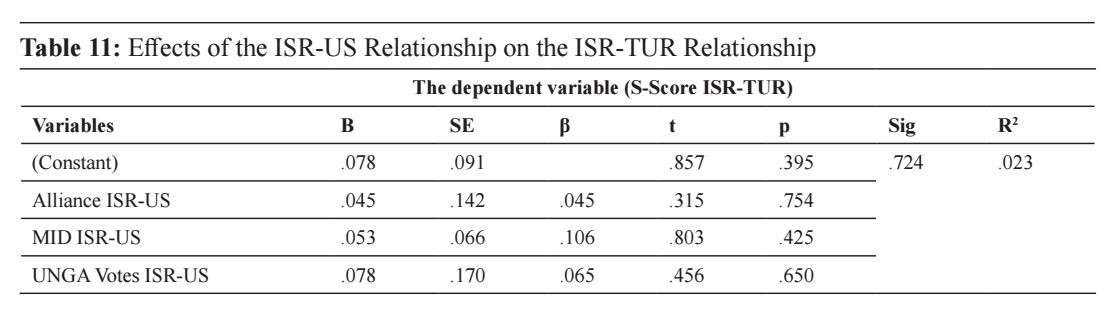

The regression analysis results regarding the effects of interest similarity between the US and Israel on the interest similarities of the US-Turkey and Turkey-Israel relationships were shown in Table 10 and Table 11, respectively.

Table 10 shows that 15% of the interest similarity between the US and Turkey can be explained by the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship. In other words, the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship affects the interest similarity of the US-Turkey relationship at a rate of 15%. At this point, the regression analysis revealed that the political similarity between the US and Israel alone in terms of alliance portfolio has an impact on the US-Turkey relationship. However, the direction of this effect is negative. Thus, it has been found that as the level of alliance portfolio between the US and Israel has increased, the level of interest similarity between the US and Turkey has decreased.

Table 11 shows that the effect of the interest similarity between the US and Israel on the Israel-Turkey relationship was not at a statistically significant level (P>.05). In other words, the interest similarity between Israel and Turkey was not affected by the interest similarity of the US-Israel relationship.

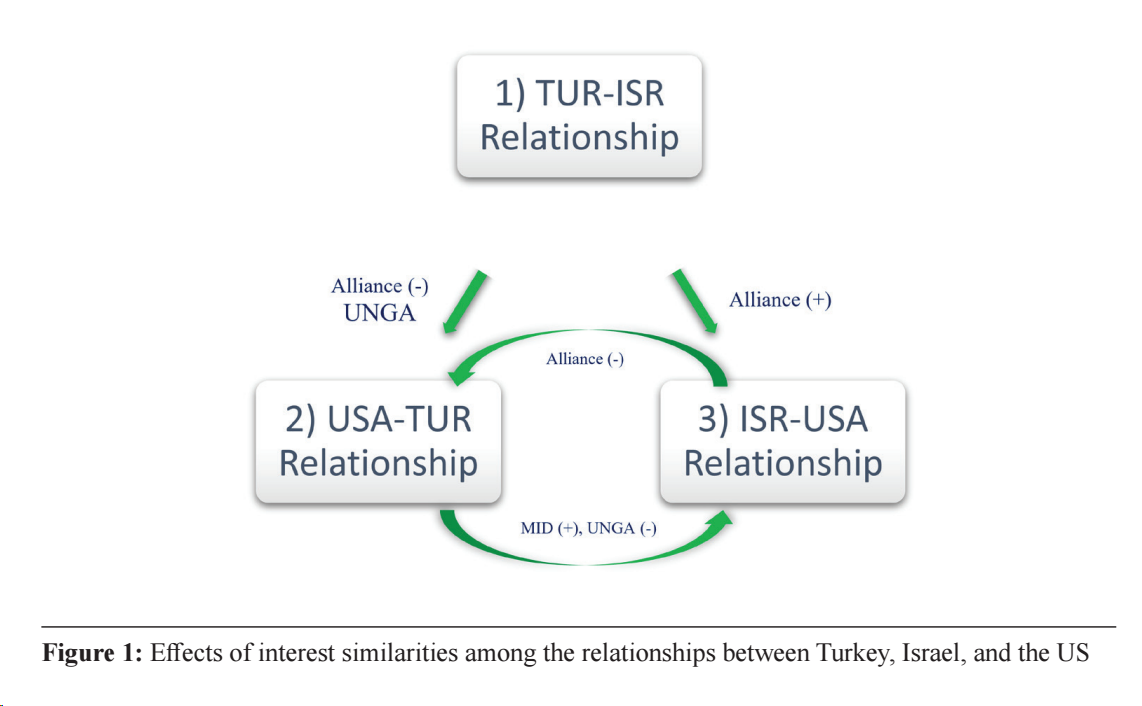

The quantitative results have revealed that the interest similarities among Turkey, Israel, and the US are interrelated. Moreover, some of the interest similarities between two countries have affected the interest similarity with the third remaining country, or have been affected by the interest similarity with the third country. Figure 1 summarizes the quantitative results below, and the green arrows show which interest similarity between two countries influences the interest similarity of another country. In addition, the “+” (positive) and “-” (negative) signs explain the factors affecting interest similarity and show the direction of the effects.

Firstly, the correlation analysis results have revealed that there is a statistically significant and weak-positive correlation between the interest similarities of the (1) Turkey-Israel and (2) US-Turkey relationships. Additionally, the regression analysis results have revealed that the interest similarity between (1) Turkey and Israel have an impact on the interest similarities between both (2) the US-Turkey and (3) the US-Israel relationships. However, the interest similarities between both (2) the US and Turkey and (3) the US and Israel have no effect on the interest similarity of (1) the Turkey-Israel relationship. On the other hand, the correlation and regression analysis results have revealed that an increase in the similarity of the UNGA votes between (1) Turkey and Israel positively affect the interest similarity of (2) the US-Turkey relationship. Interestingly, while an increase in similarity of alliance between (1) Turkey and Israel negatively affect (2) the US-Turkey relationship, an increase in the similarity of alliance between (1) Turkey and Israel positively affect (3) the US-Israel relationship. Existing literature supports that the Turkey-Israel relationship has an important role in the improvement or deterioration of relationships among these three states. For instance, in response to the harsh policy of Turkey after Israel’s declaration of Jerusalem as its eternal capital in 1980, the US sent a letter to the Ambassador of Turkey to Washington and warned that “Ankara’s policy towards Israel could negatively affect Turkish-American relations.”[61] In addition, it is expressed that the relationship to be established between Ankara and Tel Aviv will also be decisive in the Ankara-Washington relationship, since the security problem of Israel is one of the fundamental policies of the United States regarding the Middle East.[62] Thus, this research helps to better understand one of the reasons why the President of Israel visited Turkey in February 2022 to repair the weak Turkey-Israel relationship, because the regression results have shown that Israel’s alliance with Turkey positively affects Israel’s relationship with the United States.

Secondly, the correlation analysis results have revealed that there is a statistically significant and weak-negative correlation between the interest similarities of the (2) US-Turkey and (3) US-Israel relationships. Moreover, the regression analysis results have revealed that the interest similarity of (2) the US and Turkey affects the interest similarity of (3) the US-Israel relationship. Furthermore, the interest similarity of (3) the US-Israel relationship affects the interest similarity of (2) the US-Turkey relationship as well. The correlation and regression analysis results have shown that an increase in the similarity of Militarized Disputes (MID) between (2) the US and Turkey positively affects the interest similarity of (3) the US-Israel relationship. However, an increase in similarity of UNGA votes between (2) the US and Turkey negatively affects the interest similarity of (3) the US-Israel relationship. In addition, an increase in the similarity of alliance between (3) the US and Israel negatively affects the interest similarity of (2) the US-Turkey relationship. Existing literature supports these results as well. For example, it has been stated that an increase in the US-Israel relationship is based on different strategic foundations,[63] and its special relationship with the United States has been of fundamental importance for Israel.[64] The effect of Israel on the US stems from the Israel lobby’s power in affecting the decisions of the US.[65] Therefore, the influence of the lobby within the US may help to explain the power relationship between the United States and Israel.[66] Furthermore, according to Blackwill and Slocombe, “there is no other Middle East country whose definition of national interests is so closely aligned with that of the United States.”[67] On the other hand, it has been said that the US played a “catalyst” role between Israel and Turkey during the period between the 1990s and 2000s.[68] However, the global interests of the US may have clashed with Turkey’s regional interests, thereby possibly causing the interest similarity of the Turkey-US relationship to lower in recent years.

Turkey, Israel, and the US share similar strategic interests in the Middle East region in their foreign policies, which has positively affected their political similarity. The deteriorating relations between Turkey and Israel may weaken the US influence in the region and create a strategic problem for the US. Therefore, with the effect of its hegemonic power, the US has stressed that the relations between these countries should not deteriorate,[69] and the hegemonic power of the US has played a unifying role in the relations between the countries.

The historical process of relations must be considered to understand by which events the Turkey-USA and Turkey-Israel relations were affected. In this respect, when the relations were evaluated according to the interest similarity graphic shown in Appendix 5 in the historical process, the agreement in Turkey-USA relations until 1990 can be explained with the fact that Turkey and the USA considered the Soviet Union as a common threat during the Cold War Period. One of the key elements of Turkish Foreign Policy during the Cold War years (1945-1990) was to limit the influence of the Soviets on the USA and NATO. It has been stated in several studies that the agreement during this period was because of Turkey’s security concerns.[70] According to the graphic, when Turkey-Israel relations from this period are evaluated, it is understood that the relations had an up-and-down trend. The strategic imperatives of the Cold War forced countries to apply bandwagoning policies.[71] Turkey’s tendency to develop good relations with Israel largely stemmed from its alliance with the West. For this reason, Turkey acted cautiously to establish a balance between the two goals because of its interests. On the one hand, it tried to develop normal relations with Israel as required by its alliance with the United States, and on the other hand, it tried not to sever diplomatic and economic ties with the Islamic World. The period from 1961 to 1964 represents the important years in which relations with both the United States and Israel showed a low trend for Turkey. In this period, the United States withdrew Jupiter missiles from Turkey because of the Cuban Crisis, and the following year, Turkey sending a warning letter to President Johnson regarding the Cyprus issue caused Turkey to reevaluate its relations. However, this attitude of Turkey was shaped not by moving away from the USA, but by its wish to eliminate its loneliness in terms of foreign policy. The challenges in the relations with the USA also affected Turkey’s relations with Israel as a global parameter.[72] By 1974, the oil crisis caused Turkey to reconsider its relations with Israel, and the dependency on oil led Turkey to improve its economic relations with the Arab world.[73] Until the 1990s, the issues defining Turkey-Israel relations included the Arab-Israeli wars, the Palestinian issue in particular, the Cyprus issue, and the search for Arab support during Turkey’s economic problems. The low-level relations between the two countries that were kept a secret for the first forty years began to become official and clear with the change of the international system by the late 1980s.[74] For this reason, the up-and-down trend in the bilateral relations between Turkey and Israel during this period can be explained in the interest similarity graphic in Appendix 5. In brief, it can be argued that Turkey’s relations with the USA were agreeable from 1948 to 1990; however, the relations with Israel followed an up-and-down trend again, and this finding was similar to the literature.[75] Factors affecting Turkish relations with the USA and Israel in this period include security and economy.

In the 1991-2000 period, Turkey-USA relations were agreeable, and Turkey-Israel relations were stronger than in later years. In this period, important changes occurred in Turkey’s security perceptions with the 1991 Gulf War. Turkey’s Gulf policy was squeezed between its strategic relations with the USA and the US policies towards the Kurds and Saddam. For this reason, Turkey was not able to convert its relations with the United States into concrete gains.[76] In this respect, this situation was quite different for Turkey, although it was considered as the “golden age” of Turkey-USA cooperation. As Ian Lesser has noted, the Gulf War is “where the trouble started.”[77] Although the USA’s Iraqi Operation imposed risks on Turkey, Turkey aimed to protect its interests in the region by taking advantage of the US military presence in neighboring regions.[78] In the new period, the role imposed on Turkey by the USA changed; however, the relations with Turkey continued to accelerate positively. As seen in the graphic (Appendix 5), although the interest agreement with the United States decreased slightly, the cooperation continued. The 1990s brought changes not only in relations with the USA, but also with Israel. Regional problems affecting both countries brought Turkey and Israel closer together. Turkey’s problems with neighbors that supported terrorism and Israel’s experience with similar threats from Syria and Iran led to the perception of common threats between the two states. In this way, a strategic alliance was formed between the two countries. As seen in the graphic, the years between 1996 and 2000 constituted a period in which the relations were more agreeable. In brief, Turkey’s relations with the USA were agreeable between 1990 and 2001, and relations with Israel were relatively stable. Among the factors that affected the relations among Turkey, the USA, and Israel during this period, there is the conjunctural structure that changed after the Cold War. The changing conjunctural structure brought all three countries closer together.

In the period after 2001, the interest similarity between Turkey and the USA and Turkey and Israel decreased compared to previous years. The USA-Iraqi war led to a deterioration of relations between Turkey and the USA in 2003, and at the same time, caused interest differences between Turkey and Israel. There was a “sack crisis”[79] with the United States after this process, and separations started with Israel regarding the support to the Kurdish structure in Iraq.[80] The significant changes in the domestic and foreign policies of Turkey affected the separation of Turkey’s political similarity from that of the USA and Israel. The events that played roles in the change in Turkey’s domestic policy can be listed as follows: the Islamic-Ideological orientation of the Justice and Development Party, which came to power in 2002; the change in power between the military and civilian structures of Turkey; and the perception change in the Turkish public towards the USA and Israel.[81] The change of international and regional conjuncture was effective in the change of Turkey’s foreign policy. Turkey’s relations with the USA and Israel proceeded in an equal trend at this time when political resemblance caused such sharp declines in both countries. It is possible to speculate that there is a differentiation of interest with both countries in the emergence of such “co-trends.” The events, which were effective in the up-and-down trend in relations between Turkey and the USA, can be listed as follows: the US’s support for Israel in the face of the Israeli-Palestinian issue; the difference in Turkey’s approach to the Iranian nuclear program; the S-400 missiles bought by Turkey from Russia; and the different attitudes of Turkey and the USA against the structures in Syria. The fact that Turkey is experiencing some kind of “alienation” in its communication with Israel overlaps astonishingly with the fact that this foreign policy trend of Turkey is moving away from America and Europe.[82] The factors that played a major role in the deterioration of relations between Turkey and Israel during this period were: Israel's harsh interventions in the Palestinian conflict, Israel's natural gas exploration activities with Greece in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Israel's stance on the Syrian crisis. In brief, considering the period after 2001, it can be argued that the bilateral political similarity among Turkey, the USA, and Israel was parallel, and the relations had an up-and-down trend. Although the reflections of crises affecting these three countries on their internal policies were effective during this period, the new geopolitical realities in the Middle East became an important factor in determining the course of their relations.

This research has examined the interest similarity among Turkey, Israel, and the US considering quantitative data, namely MID, alliance, and UNGA votes. The research questions explore whether there is any significant correlation between the bilateral relationships of Turkey, Israel, and the US in terms of interest similarity, and how MID, alliance, and UNGA votes can affect the interest similarity among these three countries.

The findings have revealed that there are statistically significant relations among the interest similarities of Turkey, Israel, and the US. The analysis of quantitative data has shown that the interest similarity of the Turkey-Israel relationship plays an active role in affecting the US-Turkey and the US-Israel relationships. Moreover, there is a negative correlation between the interest similarity of the US-Turkey and the US-Israel relationships. The interest similarity between the US and Turkey has an impact on the interest similarity between the US and Israel, and the interest similarity between the US and Israel has an impact on the interest similarity between the US and Turkey as well. In addition, this research has revealed, depending on the analysis of quantitative data, that the similarity between two of the countries in question in terms of MID, alliance, and UNGA votes affects the interest similarity with the third remaining country.

Suggestions for future studies are presented below for those who would like to conduct further research on examining international relations among Turkey, Israel, and the US based on quantitative and/or qualitative data.

Existing literature expresses that interest similarity can be estimated by MID, alliance, and UNGA votes data. At this point, future studies can investigate which other factors cause an increase or decrease in the level of interest similarity, such as economic and military capability, cultural and diplomatic influence, and natural resources. In addition, future research can focus on the influence of country leaders on relationships.

In this research, interest similarity score was calculated by using MID, alliance, and UNGA votes with the S-Score method. However, although the S-Score method was suitable for standardizing the UNGA votes data, it was not entirely suitable for alliance and MID data. Therefore, additional rules shown in Table 2 were employed to figure out this issue towards reducing miscalculation. However, a new statistical method that can be used to standardize alliance and MID data is still needed.

The examination of interest similarity has been performed by using correlation and regression analysis methods in this research. Future studies can employ alternative analysis methods, such as artificial intelligence or artificial neural networks. These kinds of methods can enable researchers to predict the future of such relationships from retrospective data.

Finally, this research has just focused on the similarity of the votes used in the United Nations General Assembly. Therefore, future studies can categorize the UNGA votes of Turkey, Israel, and the US to reveal which issues they agree on and/or which issues they conflict on.

This research was supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TUBITAK) Post-Doctoral Scholarship Program (Grant number: 1059B191900998).

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TTS9Z9

Notes

[1] Eric Gartzke, “Kant We All Just Get Along? Opportunity, Willingness, and the Origins of the Democratic Peace,” American Journal of Political Science 42, no. 1 (1998): 1-27.[2] Eric Gartzke, “The Capitalist Peace,” American Journal of Political Science 51, no.1 (2007): 171.

[3] Erik Voeten, “Data and Analyses of Voting in the United Nations General Assembly,” in Routledge Handbook of International Organization, ed., Bob Reinalda, (London: Routledge, 2013), 62.

[4] William B. Quandt, ed., Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey and Israel in the New Middle East (Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011): 13.

[5] Efraim Inbar, “The Resilience of Israeli–Turkish Relations,” Israel Affairs 11, no. 4 (2005): 591-607.

[6] Bülent Alirıza, “The Turkish-Israeli Crisis and U.S.-Turkish Relations,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 20, 2011, accessed date August 15, 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/turkish-israeli-crisis-and-us-turkish-relations.

[7] Dan Arbell, “The US-Turkey-Israel Triangle,” Brookings: Center for Middle East Policy Analysis Paper, no. 34 (2014): 2.

[8] Steven A. Cook, “The USA, Turkey, and the Middle East: Continuities, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Turkish Studies 12, no. 4 (2011): 720.

[9] Gregory F. Gause III, “The US-Israeli-Turkish Strategic Triangle: Cold War Structures and Domestic Political Processes,” in Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey and Israel in the New Middle East, ed., William B. Quandt, (Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011), 23.

[10] Ellen Laipson, Philip Zelikow, and Brantly Womack, “Strategic Perspectives: Comments and Discussion,” in Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey and Israel in the New Middle East, ed., William B. Quandt, (Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011), 67.

[11] Ersel Aydınlı and Onur Erpul, “Elite Change and the Inception, Duration, and Demise of the Turkish–Israeli Alliance,” Foreign Policy Analysis 17, no. 2 (2021): 5.

[12] Efrat Aviv, “The Turkish Government’s Attitude to Israel and Zionism as Reflected in Israel’s Military Operations 2000–2010,” Israel Affairs 25, no. 2 (2019): 281-306.

[13] Carol Migdalovitz, Turkey: Selected Foreign Policy Issues and US Views (Washington, DC: Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, 2008), 14. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA486490

[14] Bülent Aliriza and Bülent Aras, US-Turkish Relations: A Review at the Beginning of the Third Decade of the Post-Cold War Era, (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2012).

[15] Kıvanç Ulusoy, “Turkey and Israel: Changing Patterns of Alliances in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 22, no. 3 (2020): 415-430.

[16] Sholomo Brom, “The Israeli-Turkish Relationship,” in Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey and Israel in the New Middle East, ed., William B. Quandt, (Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011), 58.

[17] “Türkiye-İsrail ilişkilerinde Yeni Dönüm Noktası,” Deutsche Welle, March 9, 2022, accessed date March 9, 2022. https://www.dw.com/tr/t%C3%BCrkiye-i%CC%87srail-ili%C5%9Fkilerinde-yeni-d%C3%B6n%C3%BCm-noktas%C4%B1/a-61072319.

[18] Anat Lapidot-Firilla, “Turkey’s Search for a ‘Third Option’ and Its Impact on Relations with US and Israel,” Turkish Policy Quarterly 4, no. 1 (2005): 1-9.

[19] Kevin John Sweeney and Omar M. G. Keshk, “The Similarity of States: Using S to Compute Dyadic Interest Similarity,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 22, no. 2 (2005): 165-187.

[20] Ibid.

[21]MID data is an important determinant in revealing the political closeness of states, as they reflect the differentiation of interests between states. States with similar foreign policy interests are less likely to engage in military conflicts. Since most of the conflicts between states occur between states with different interests, the absence of conflict between the three countries is an indication that the countries have similar interests, but it is also an indication of high political similarity. In this study, although the extraction of MID data does not affect the S-score variable statistically, it is evidence that the relations between the three countries have made strategic cooperation progress in line with similar interests, and that they do not experience a conflict of interest that will lead to conflict. Therefore, the MID variable continues to be important data in revealing the political similarity between the three countries.

[22] Glenn H. Snyder, Alliance Politics (New York: Cornell University Press, 1997); James D. Morrow, “Alliances and Asymmetry: An Alternative to the Capability Aggregation Model of Alliances,” American Journal of Political Science 35, no. 4 (1991): 904-933.

[23] Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, The War Trap (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

[24] Curtis S. Signorino and Jeffrey M. Ritter. “Tau-b or not tau-b: Measuring the Similarity of Foreign Policy Positions,” International Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (1999): 115-144.

[25] Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, “Measuring Systemic Polarity,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 19, no. 2 (1975): 187-216.

[26] Stephen Watts et al., Understanding Conflict Trends: A Review of the Social Science Literature on the Causes of Conflict (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017), 14.

[27] Charles S. Gochman and Zeev Maoz, “Militarized Interstate Disputes 1816-1976,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 28, no. 4 (1984): 587.

[28] Eyasu Habtemariam, Tshilidzi Marwala, and Monica Lagazio, “Artificial Intelligence for Conflict Management,” in Proceedings IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2005. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=1556310

[29] Zeev Maoz et al., “The Dyadic Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs) Dataset Version 3.0: Logic, Characteristics, and Comparisons to Alternative Datasets,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63, no. 3 (2019): 815.

[30] James D. Fearon, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49, no. 3 (1995): 379-414, 383.

[31] Frank M. Häge and Simon Hug, “Consensus Decisions and Similarity Measures in International Organizations,” International Interactions 42, no. 3 (2016): 503-529.

[32] Michael A. Bailey, Anton Strezhnev, and Erik Voeten, “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 2 (2017): 430-456; M. Margaret Ball, “Bloc voting in the General Assembly,” International Organization 5, no. 1 (1951): 3-31; Steven Holloway, “Forty years of United Nations General Assembly Voting,” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 23, no. 2 (1990): 279-296.

[33] Voeten, “Data and analyses of voting in the United Nations General Assembly,” 54-66.

[34] Soo Yeon Kim and Bruce Russett, “The New Politics of Voting Alignments in the United Nations General Assembly,” International organization 50, no. 4 (1996): 629.

[35] Mohammad Zahidul Islam Khan, “Is Voting Patterns at the United Nations General Assembly a Useful Way to Understand a Country’s Policy Inclinations: Bangladesh’s Voting Records at the United Nations General Assembly,” SAGE Open 10, no. 4 (2020): 1-16.

[36] Bailey et al., “Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data,” 437.

[37] Kevin John Sweeney, “A Dyadic Theory of Conflict: Power and Interests in World Polities,” PhD diss., (The Ohio State University, 2004).

[38] Georg Strüver, “What Friends are Made of: Bilateral Linkages and Domestic Drivers of Foreign Policy Alignment with China,” Foreign Policy Analysis 12, no. 2 (2016): 170-191.

[39] Alastair Iain Johnston, “China’s Militarized Interstate Dispute Behaviour 1949–1992: A First Cut at the Data,” The China Quarterly no. 153, (1998): 1-30.

[40] R.D.P. Sampath Rajapakshe, “Similarity of Interests between Governments and Its Impact on their Bilateral Relations: Case study of China-Sri Lanka Relations,” International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology 2, no. 11 (2015): 40-53.

[41] Jutta Weldes, “Constructing National Interests,” European Journal of International Relations 2, no. 3 (1996): 275.

[42] Hans Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), 242.

[43] Sweeney and Keshk, “The similarity of states: Using S to compute dyadic interest similarity,” 165.

[44] Deng Yong, “The Chinese conception of National Interest in International Relations,” The China Quaterly 154, (1998): 308.

[45] In measuring the foreign policy similarity of the states, Kendall’s Tau-b correlation coefficient revealed the relationships between binary and ordinal variables, but since Signorino and Ritter’s S-score yielded more explanatory results than the Tau-b measure, foreign policy in statistical analyses of international relations became the dominant measure of their positions. See: Frank M. Häge, “Choice or circumstance? Adjusting Measures of Foreign Policy Similarity for Chance Agreement,” Political Analysis 19, no. 3, (2011): 287.

[46] Signorino and Ritter, “Tau-b or not tau-b: Measuring the Similarity of Foreign Policy Positions,” 126.

[47] Ibid., 115-144.

[48] Garrett Alan Heckman, “Power Capabilities and Similarity of Interests: A Test of the Power Transition Theory,” MS thesis, (Londen School of Economics, 2009): 712.

[49] Navin A. Bapat, “The Internationalization of Terrorist Campaigns,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 24, no. 4 (2007): 265-280.

[50] Douglas M. Gibler and Meredith Reid Sarkees, “Measuring Alliances: The Correlates of War Formal Interstate Alliance Dataset, 1816-2000,” Journal of Peace Research 41, no. 2 (2004): 211-222.

[51] Zeev Maoz, et al., “The Dyadic Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs) Dataset Version 3.0,” 811-835.

[52] Erik Voeten, Anton Strezhnev, and Michael Bailey, United Nations General Assembly Voting Data, V27 (2009), Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LEJUQZ

[53] David J. Singer, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey, “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965,” in Peace, War, and Numbers, Bruce Russett ed, (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972), 19-48.

[54] “The Correlates of War Project – Data Sets,” Correlates of War, accessed date April 10, 2020, https://correlatesofwar.org/data-sets

[55] Erik Voeten, Anton Strezhnev, and Michael Bailey, United Nations General Assembly Voting Data, V27.

[56] Gibler and Sarkees, “Measuring Alliances,” 211-222.

[57] Daniel M. Jones, Stuart A. Bremer, and J. David Singer, “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1816–1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical Patterns,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 15, no. 2 (1996): 163.

[58] Paul F. Diehl and Gary Goertz, War and Peace in International Rivalry (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2001): 281-298.

[59] Bailey et al., “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data,” 430–456.

[60] Hyung Min Kim, “Comparing Measures of National Power,” International Political Science Review 31, no. 4 (2010): 405.

[61] Mehmet Kaya, “Türk-İsrail İlişkileri ve Filistin,” Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 9, no. 18 (2019): 1043-1066.

[62] Tayyar Arı, “Türk-Amerikan İlişkileri: Sistemdeki Değişim Sorunu mu?” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 13, (2008): 17-35.

[63] Bernard Reich and Shannon Powers, “The United States and Israel: The Nature of a Special Relationship,” in The Middle East and the United States, Student Economy Edition (New York: Routledge, 2016): 227-243.

[64] Robert O. Freedman, Israel’s First Fifty Years (Florida: University Press of Florida, 2000): 200.

[65] Said Al-Haj, “The Israel Factor in Tense Turkey-US Relations,” Middle East Monitor, August 7, 2018, accessed date November 9, 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180807-the-israel-factor-in-tense-turkey-us-relations/; Shira Efron, Future of Israeli-Turkish Relations (Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, 2018); John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, “The Israel Lobby,” in The Domestic Sources of American Foreign Policy: Insights and Evidence, ed., James M. McCormick, (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, 2012): 89-103.

[66] Daniel Bosley, “The United States and Israel: A (neo) Realist Relationship,” Spire Journal of Law, Politics and Societies 3, no. 2 (2008): 33-52.

[67] Robert D. Blackwill and Slocombe B. Walter. “Israel: A Strategic Asset for the United States,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 31, 2011, accessed date November 9, 2020. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/israel-strategic-asset-united-states-0

[68] Muzaffer Ercan Yılmaz, “Soğuk Savaş Sonrası Dönemde Türkiye-İsrail İlişkileri,” Akademik Orta Doğu 4, no. 2 (2010): 51.

[69] Ken Liu and Chris Taylor, “United States-Turkey-Iran: Strategic Options for the Coming Decade,” Institute of Politics, 2011, accessed date November 9, 2020, XX. https://iop.harvard.edu/sites/default/files_new/Programs/US_TurkeyIranPolicyPaper.pdf

[70] Erkan Ertosun, “Türkiye’nin Filistin Politikasında ABD ya da AB Çizgisi: Güvenlik Etkeninin Belirleyiciliği,” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 7, no. 28 (2011): 57-88.

[71] Kostas Ifantis, The US and Turkey in the fog of Regional Uncertainty, GreeSe Paper 73 (London: Hellenic Observatory LSE, 2013).

[72] Ahmet Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik (İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2009), 418.

[73] Alon Liel, Turkey in the Middle East: Oil, Islam and Politics (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001), 27-101.

[74] Jacob Abadi, “Israel and Turkey: from Covert to Overt Relations,” Journal of Conflict Studies 15, no. 2 (1995): 1.

[75] Yavuz Turan, Çuvallayan İttifak, (Ankara: Destek Yayınları, 2006), 87-88; Ayça Eminoğlu, “Tarihsel Süreçte Türkiye İsrail İlişkilerinin Değişen Yapısı,” Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü 7, no.15 (2016): 88.

[76] Tayyar Arı, Yükselen Güç: Türkiye-ABD İlişkileri ve Orta Doğu (İstanbul: Marmara Kitap Merkezi, 2010), 43.

[77] Ian O. Lesser, “Turkey, the United States, and the Geopolitics of Delusion,” Survival 48, no. 3 (2006): 2.

[78] Stephen, F. Larrabee, Troubled partnership: US-Turkish Relations in an Era of Global Geopolitical Change (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2010), 4.

[79] On July 4th, 2003, Turkish soldiers were arrested with a sack over their heads in Sulaymaniyah, Northern Iraq, by US soldiers. The sack crisis was seen as the US’s revenge for Turkey’s rejection of the March 1st, 2003, parliamentary resolution. See: Ayşe Ömür Atmaca, “Yeni Dünyada Eski Oyun: Eleştirel Perspektiften Türk-Amerikan İlişkileri,” Ortadoğu Etütleri 3, no. 1 (2011): 177.

[80] Banu Eligür, “Crisis in Turkish–Israeli Relations (December 2008–June 2011): From Partnership to Enmity,” Middle Eastern Studies 48, no. 3, (2012): 431.

[81] Matthew S. Cohen and Charles D. Freilich, “Breakdown and Possible Restart: Turkish–Israeli Relations under the AKP,” Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 8, no.1, (2014): 45.

[82] Al-Haj, “The Israel Factor.”

Bibliography

Abadi, Jacob. “Israel and Turkey: from Covert to Overt Relations.” Journal of Conflict Studies 15, no. 2 (1995): 1-17.

Al-Haj, Said. “The Israel Factor in Tense Turkey-US Relations.” Middle East Monitor. August 7, 2018. Accessed date November 9, 2020. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180807-the-israel-factor-in-tense-turkey-us-relations/

Alirıza, Bülent, and Bülent Aras. US-Turkish Relations: A Review at the Beginning of the Third Decade of the Post-Cold War Era. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2012.

Alirıza, Bülent. “The Turkish-Israeli Crisis and U.S.-Turkish Relations.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. September 20, 2011. Accessed date August 15, 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/turkish-israeli-crisis-and-us-turkish-relations.

Arbell, Dan. “The US-Turkey-Israel Triangle.” Brookings: Center for Middle East Policy Analysis Paper, no. 34 (2014): 1-48.

Arı, Tayyar. “Türk-Amerikan İlişkileri: Sistemdeki Değişim Sorunu mu?” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 13, (2008): 17-35.

——. Yükselen Güç: Türkiye-ABD İlişkileri ve Orta Doğu. İstanbul: Marmara Kitap Merkezi, 2010.

Atmaca, Ayşe Ömür. “Yeni Dünyada Eski Oyun: Eleştirel Perspektiften Türk-Amerikan İlişkileri,” Ortadoğu Etütleri 3, no. 1 (2011): 157-192.

Aviv, Efrat. “The Turkish Government’s Attitude to Israel and Zionism as Reflected in Israel’s Military Operations 2000–2010.” Israel Affairs 25, no. 2 (2019): 281-306.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Onur Erpul. “Elite Change and the Inception, Duration, and Demise of the Turkish–Israeli Alliance.” Foreign Policy Analysis 17, no. 2 (2021): 1-21.

Bailey, Michael A., Anton Strezhnev, and Erik Voeten, “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 2 (2017): 430-456.

Ball, M. Margaret. “Bloc voting in the General Assembly.” International Organization 5, no. 1 (1951): 3-31.

Bapat, Navin A. “The Internationalization of Terrorist Campaigns.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 24, no. 4 (2007): 265-280.

Blackwill, Robert D., and Slocombe B. Walter. “Israel: A Strategic Asset for the United States.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. October 31, 2011. Accessed date November 9, 2020. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/israel-strategic-asset-united-states-0

Bosley, Daniel. “The United States and Israel: A (neo) Realist Relationship.” Spire Journal of Law, Politics and Societies 3, no. 2 (2008): 33-52.

Brom, Sholomo. “The Israeli-Turkish Relationship.” In Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey and Israel in the New Middle East, edited by William B. Quandt, 45-59. Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011.

Cohen, Matthew S., and Charles D. Freilich. “Breakdown and Possible Restart: Turkish–Israeli Relations under the AKP.” Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 8, no.1, (2014): 39-55.

Cook, Steven A. “The USA, Turkey, and the Middle East: Continuities, Challenges, and Opportunities.” Turkish Studies 12, no. 4 (2011): 717-726.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet. Stratejik Derinlik. İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2009.

de Mesquita, Bruce Bueno. “Measuring Systemic Polarity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 19, no. 2 (1975): 187-216.

——. The War Trap. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

Diehl, Paul F., and Gary Goertz. War and Peace in International Rivalry. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Efron, Shira. Future of Israeli-Turkish Relations. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, 2018.

Eligür, Banu Eligür. “Crisis in Turkish–Israeli Relations (December 2008–June 2011): From Partnership to Enmity.” Middle Eastern Studies 48, no. 3, (2012): 429-459.

Eminoğlu, Ayça. “Tarihsel Süreçte Türkiye İsrail İlişkilerinin Değişen Yapısı.” Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü 7, no.15 (2016): 88-106.

Ertosun, Erkan. “Türkiye’nin Filistin Politikasında ABD ya da AB Çizgisi: Güvenlik Etkeninin Belirleyiciliği.” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika 7, no. 28 (2011): 57-88.

Fearon, James D. “Rationalist Explanations for War.” International Organization 49, no. 3 (1995): 379-414.

Freedman, Robert O. Israel’s First Fifty Years. Florida: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Gartzke, Eric. “The Capitalist Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 51, no.1 (2007): 166-191.

——. “Kant We All Just Get Along? Opportunity, Willingness, and the Origins of the Democratic Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 42, no. 1 (1998): 1-27.

Gause III, Gregory F. “The US-Israeli-Turkish Strategic Triangle: Cold War Structures and Domestic Political Processes.” In Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey, and Israel in the New Middle East, edited by William B. Quandt, 22-40. Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011.

Gibler, Douglas M., and Meredith Reid Sarkees. “Measuring Alliances: The Correlates of War Formal Interstate Alliance Dataset, 1816-2000.” Journal of Peace Research 41, no. 2 (2004): 211-222.

Gochman, Charles S., and Zeev Maoz. “Militarized Interstate Disputes 1816-1976.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 28, no. 4 (1984): 585-616.

Habtemariam, Eyasu, Tshilidzi Marwala, and Monica Lagazio. “Artificial Intelligence for Conflict Management.” In Proceedings IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2005. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=1556310

Häge, Frank M. “Choice or circumstance? Adjusting Measures of Foreign Policy Similarity for Chance Agreement.” Political Analysis 19, no. 3, (2011): 287-305.

Häge, Frank M., and Simon Hug. “Consensus Decisions and Similarity Measures in International Organizations.” International Interactions 42, no. 3 (2016): 503-529.

Heckman, Garrett Alan. “Power Capabilities and Similarity of Interests: A Test of the Power Transition Theory.” Master of Science thesis. Londen School of Economics, 2009.

Holloway, Steven. “Forty years of United Nations General Assembly Voting.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 23, no. 2 (1990): 279-296.

Ifantis, Kostas. The US and Turkey in the fog of Regional Uncertainty, GreeSe Paper 73. London: Hellenic Observatory LSE, 2013. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50987/1/__libfile_REPOSITORY_Content_Hellenic%20

Observatory%20(inc.%20GreeSE%20Papers)_GreeSE%20Papers_GreeSE%20No73.pdf

Inbar, Efraim. “The Resilience of Israeli–Turkish Relations.” Israel Affairs 11, no. 4 (2005): 591-607.

Johnston, Alastair Iain. “China’s Militarized Interstate Dispute Behavior 1949–1992: A First Cut at the Data.” The China Quarterly no. 153, (1998): 1-30.

Jones, Daniel M., Stuart A. Bremer, and J. David Singer. “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1816–1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical Patterns.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 15, no. 2 (1996): 163-213.

Kaya, Mehmet. “Türk-İsrail İlişkileri ve Filistin.” Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 9, no. 18 (2019): 1043-1066.

Khan, Mohammad Zahidul Islam. “Is Voting Patterns at the United Nations General Assembly a Useful Way to Understand a Country’s Policy Inclinations: Bangladesh’s Voting Records at the United Nations General Assembly.” SAGE Open 10, no. 4 (2020): 1-16.

Kim, Hyung Min. “Comparing Measures of National Power,” International Political Science Review 31, no. 4 (2010): 405-427.

Kim, Soo Yeon, and Bruce Russett. “The New Politics of Voting Alignments in the United Nations General Assembly,” International organization 50, no. 4 (1996): 629-652.

Laipson, Ellen, Philip Zelikow, and Brantly Womack. “Strategic Perspectives: Comments and Discussion.” In Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey, and Israel in the New Middle East, edited by William B. Quandt, 60-72. Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011.

Lapidot-Firilla, Anat. “Turkey’s Search for a ‘Third Option’ and Its Impact on Relations with US and Israel.” Turkish Policy Quarterly 4, no. 1 (2005): 1-9.

Larrabee, Stephen F. Troubled partnership: US-Turkish Relations in an Era of Global Geopolitical Change. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2010.

Lesser, Ian O. “Turkey, the United States, and the Geopolitics of Delusion.” Survival 48, no. 3 (2006): 1-13.

Liel, Alon. Turkey in the Middle East: Oil, Islam, and Politics, 27-101. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001.

Liu, Ken, and Chris Taylor. “United States-Turkey-Iran: Strategic Options for the Coming Decade,” Institute of Politics. 2011. Accessed date November 9, 2020. https://iop.harvard.edu/sites/default/files_new/Programs/US_TurkeyIranPolicyPaper.pdf

Maoz, Zeev et al. “The Dyadic Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs) Dataset Version 3.0: Logic, Characteristics, and Comparisons to Alternative Datasets.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63, no. 3 (2019): 811-835.

Mearsheimer, John, and Stephen Walt. “The Israel Lobby.” In The Domestic Sources of American Foreign Policy: Insights and Evidence, edited by James M. McCormick, 89-103. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, 2012.

Migdalovitz, Carol. Turkey: Selected Foreign Policy Issues and US Views. Washington, DC: Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, 2008. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA486490

Morgenthau, Hans. Politics Among Nations. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951.

Morrow, James D. “Alliances and Asymmetry: An Alternative to the Capability Aggregation Model of Alliances.” American Journal of Political Science 35, no. 4 (1991): 904-933.

Quandt, William B., ed. Troubled Triangle: The United States, Turkey, and Israel in the New Middle East. Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2011.

Rajapakshe, R.D.P. Sampath. “Similarity of Interests between Governments and Its Impact on their Bilateral Relations: Case study of China-Sri Lanka Relations.” International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology 2, no. 11 (2015): 40-53.

Reich, Bernard, and Shannon Powers. “The United States and Israel: The Nature of a Special Relationship.” In The Middle East and the United States, Student Economy Edition, 227-243. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Signorino, Curtis S., and Jeffrey M. Ritter. “Tau-b or not tau-b: Measuring the Similarity of Foreign Policy Positions.” International Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (1999): 115-144.

Singer, David J., Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965.” In Peace, War, and Numbers, edited by Bruce Russett, 19-48. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972.

Snyder, Glenn H. Alliance Politics. New York: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Strüver, Georg. “What Friends are Made of: Bilateral Linkages and Domestic Drivers of Foreign Policy Alignment with China.” Foreign Policy Analysis 12, no. 2 (2016): 170-191.

Sweeney, Kevin John. “A Dyadic Theory of Conflict: Power and Interests in World Polities.” PhD dissertation. The Ohio State University, 2004.

Sweeney, Kevin John, and Omar M. G. Keshk. “The Similarity of States: Using S to Compute Dyadic Interest Similarity.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 22, no. 2 (2005): 165-187.