Tayyar Arı, Bursa Uludağ University

Özge Gökçen Çetindişli, Independent Researcher

Abstract

This empirical study, grounded in securitization theory, questions whether the security utterances of former U.S. President Donald Trump on North Korea between January 20, 2017, and June 12, 2018, constituted only a securitizing move or evolved into a successful securitization practice. The research employs a hybrid methodology, combining discourse and content analyses supported by quantitative data. The focus is on analyzing the discourse within a corpus of 44 securitization statements made by the president. These statements were discerned through a comprehensive review of all the president's public remarks throughout the designated period, using queries such as “North Korea,” “Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK),” “Kim Jong Un,” etc. Employing discourse analysis, the study reveals the referent objects and securitization arguments in these statements. The data gleaned from these statements is subsequently analyzed utilizing content analysis methodology. This study also evaluates the securitization discourse by examining its compliance with the facilitating conditions of an effective securitization rhetoric, a capable securitizer, and an audience-acceptable threat selection. Subsequently, it discusses the efficacy of the securitization discourse in terms of the two principal parameters proposed by the Copenhagen School: audience acceptance of the threat narrative contained in the securitizing moves, and the adoption of extraordinary measures.

Introduction

Securitization theory (ST),[i] proposed by the Copenhagen School (CS), is rooted in the analysis of speech acts, wherein political or security elites assert that a particular issue constitutes an existential threat[ii] to a crucial referent object. However, the critical point is that the utterance of the term “security” does not in itself constitute securitization; rather, it represents a securitizing move. It is the acceptance by a significant audience of the depiction of an existential threat necessitating “urgency of emergency”[iii] that signifies a case of “successful” securitization.[iv]

The practical implications of this theoretical framework can be observed in the policy approach of former President of the United States (U.S.), Donald Trump, toward North Korea. Indeed, since the early 1990s, when U.S. officials became aware that North Korea was actively pursuing nuclear weapons capability, subsequent U.S. administrations have used a combination of pressure, deterrence, and diplomacy to mitigate the threat emanating from a nuclear-armed North Korea. After coming to power, President Trump declared the ineffectiveness of the “era of strategic patience[v] with the North Korean regime,” explicitly stating that “patience has failed and is over.”[vi] He emphasized the need for a new phase, conveying the impression that his approach would be different from the previous ones.[vii]

Thus, the new administration soon made it clear that “North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons is an urgent national security threat and a top foreign policy priority.”[viii] Consequently, the administration adopted a campaign of “maximum pressure” specifically designed to force Pyongyang into complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization.[ix]

Many aspects of the officially announced policy were like the instruments of previous administrations: economic pressure, etc. However, unlike his predecessors, Trump’s discourse exhibited a more confrontational, direct, and proactive approach. In their statements, President Trump and his administration have consistently emphasized the consideration of the military option, with indications of preparedness for potential conflict.[x] An illustrative instance is found in the following tweet by President Trump:

President Trump: “Military solutions are now fully in place, locked and loaded, should North Korea act unwisely. Hopefully Kim Jong Un will find another path!”[xi]

This aggressive rhetoric, which has greatly increased tensions on the Korean Peninsula, reached a point where President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un traded in mutual bellicose public insults. As Trump threatened to “totally destroy North Korea”[xii] at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), Kim Jong Un vowed to “surely and definitely tame the mentally deranged U.S. dotard with fire.”[xiii]

Additionally, this assertive stance was formalized in Trump’s National Security Strategy (NSS), released in mid-December 2017. In this document, the president made 16 references to North Korea, a notable increase from the three mentions in the 2015 NSS. On the opening page, he unequivocally stated, “North Korea seeks the capability to kill millions of Americans with nuclear weapons.”[xiv]

Drawing on these arguments, this article aims to assess whether the discourse of then U.S. President Donald Trump concerning the designation of North Korea as a security threat persisted as merely securitizing moves or transformed into successful securitization practice. The study’s time frame was established as the period spanning from January 20, 2017, to June 12, 2018. The date of January 20, 2017, was based on the date of the inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the United States. The date of June 12, 2018, was determined based on the meeting that took place in Singapore between the leaders of the U.S. and the DPRK, which was hailed as “an important milestone” by the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General.[xv] This historical summit is considered a tangible manifestation of a desecuritization effort, involving the “shifting of issues out of emergency mode and into the normal bargaining process of the political sphere.”[xvi] This perspective is supported by Trump’s remarks shortly after the summit: “…everybody can now feel much safer than the day I took office. There is no longer a nuclear threat from North Korea…”[xvii] and “I have solved that problem (North Korea).”[xviii]

The motivation to undertake this topic stems from identifying a gap in the literature following an extensive literature review. Nearly 28 years have passed since the seminal texts[xix] on securitization were published. During that time, the theory has been the subject of many theoretical and empirical studies, revealing both its achievements as well as its challenges.[xx] Despite its Western European origins and focus,[xxi] ST has made remarkable progress outside that region[xxii] and has been applied in the analysis of diverse cases including migration,[xxiii] climate change,[xxiv] refugees,[xxv] and even epidemiological threats.[xxvi]

Nevertheless, with extensive utilization of the framework to analyze various issues, and the numerous studies[xxvii] analyzing the U.S. administration’s policies towards Pyongyang, the application of ST to U.S. policy toward North Korea remains conspicuously understudied. The most relevant piece of literature on this subject was published by Hazel Smith 23 years ago.[xxviii] Instead of evaluating the U.S. approach to Pyongyang using a securitization framework, Smith criticized the coercive nature of the securitization perspective and contended that this paradigm provided an insufficient guide for U.S. policymakers in dealing with the North Korean problem.

The unique contribution of this study stems from the adoption of a hybrid methodology,[xxix] combining discourse and methods, supported by quantitative data. The study is primarily based, however, on the discourse analysis of President Trump’s statements during the specified time interval.

According to the CS, the main method for studies exploring securitization is discourse analysis, and the determinant criterion of security is textual.[xxx] Wæver underscored this assertion with the following statement:

Discourse analysis works on public texts. It does not try to get to the thoughts or motives of the actors, their hidden intentions, or secret plans…one stays at the level of discourse…one works on public, open sources and uses them for what they are, not as indicators of something else. What interests us is neither what individual decision-makers really believe, nor what are shared beliefs among a population (although the latter comes closer), but which codes are used when actors relate to each other.[xxxi]

Accordingly, the analysis employs both primary and secondary data sources. Primary sources encompass an examination of Trump’s speeches, remarks, Congressional debates, press briefings, meeting readouts, letters, NSS documents from 2015 to 2017, and his Twitter archive.[xxxii] In addition, the study conducts an analysis of U.S. federal laws, executive orders, United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions, as well as other relevant data available on the official websites of each institution.[xxxiii] Secondary sources included prior academic studies, published reports on the subject, opinion polls, and the online editions of The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) and USA Today.

The study imposed an initial constraint on President Trump’s discourse by delineating a specific time frame. Subsequently, a second limitation was applied through a systematic query of keywords, including “North Korea,” “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK),” “Kim Jong Un,” “Pyongyang,” “rogue state/regime,” “nuclear test,” and “nuclear threat/danger/problem/risk,” within the texts during this defined period. Following the review, 44 statements made by President Trump were identified that contained at least two keywords such as “North Korea” and “threat.” This securitization corpus incorporates 7 tweets, 36 public statements, and the 2017 NSS.

The research employs a content analysis to determine which referent objects the president claimed were existentially threatened, how often he referred to them, and how often he used which arguments for securitization. Subsequently, their performative effects in the process were also evaluated through discourse analysis. In so doing, the study makes a novel contribution to the field of securitization regarding North Korea by presenting a previously underexplored case study.

In this framework, this article adopts a five-section structure. The first section introduces the empirical case study, details the methodology employed for data collection and analysis, and provides a brief review of literature. The second section offers an overview of security construction within the theoretical framework of the Copenhagen School securitization theory. The third section addresses the study’s core research questions, dissecting the identities of key units within the securitization process. This section is organized into four distinct subsections, each focusing on a specific unit: the securitizing actor, the referent object of security, functional actors, and the audience. The analysis commences by identifying then U.S. President Donald Trump as the securitizing actor. A detailed examination of the rhetorical elements within his statements is undertaken to uncover the arguments employed to legitimize his securitizing moves. This analysis then assesses the discourses’ compliance with the facilitating conditions established by the CS to guide empirical research. Subsequently, the referent objects of security are identified through a rigorous discourse analysis. Data extracted from The Wall Street Journal and USA Today, representing the media as functional actors, are then briefly examined. The audience subsection begins by delineating the specific audience targeted by Trump’s securitization rhetoric. To measure the audience’s reception of the ‘threat narrative,’ this study analyzes public opinion poll data alongside voting patterns on relevant issues within legislative bodies (e.g., the U.S. Congress) and the United Nations. Given that the implementation of emergency measures is contingent upon securing audience acceptance, a comprehensive analysis of this critical operational dynamic within the securitization process is presented in the fourth section, following the audience analysis. The study concludes with an assessment of the efficacy of the Trump administration’s securitization discourse concerning North Korea.

Subjectivity and Construction of Security

The CS has expanded the conceptualization of security beyond the traditional paradigm rooted in the logic of “survival in the face of existential threats.”[xxxiv] Contrary to the realist paradigm, the CS approach disregards conceptualizing security by an objectivist logic that does not change according to states, individuals, or conditions. The CS also differs from the neorealist perspective, which underlines the significance of the international structure in shaping states’ strategic conduct,[xxxv] and from the subjective security framework inherent in neoclassical realism. Conversely, some commonalities emerge between the neoclassical realist approach and the CS, particularly in their emphasis on the centrality of “statesmen” in determining the security dynamics.[xxxvi]

Nevertheless, neoclassical realism directs its attention towards elucidating how material capacity and the distribution of power are comprehended and implemented by actors.[xxxvii] Neoclassical realists broaden their analyses to encompass operational codes such as age, beliefs, perceptions of decision-making and policy implementation, the strategic culture of the country, etc. They contend that these factors characterize the foreign policy behavior of political leaders. Moreover, in the neoclassical realist framework, leaders’ decisions, which are inherently decisive, are considered subjective[xxxviii] in that they are made independent of audience approval.

However, the CS argues that there are no objective threats out there waiting to be discovered, and even if they exist, security is based on a highly political and intersubjective process in which issues are transformed into security threats through a series of events initiated by an empowered securitizing actor: “the securitizing speech act/move” (in which a securitizer implies that the existence of a certain referent object is under threat if not acted upon immediately by stating a point of no return); “the audience”; and the taking of extraordinary measures (which is a deviation from whatever is considered normal until an exception was installed) [xxxix] to overcome a threat.[xl]

Put differently, the CS posits that issues are prioritized and constructed as security threats through speech acts in which the securitizing actor persuades the audience that the given issue poses an existential threat to the referent object that needs to be protected. Nevertheless, the labeling of something as a security issue via speech acts by individuals or groups does not ensure that it necessarily becomes securitized. The process of securitization is only completed when the audience adopts this speech act, and its actual “success” is determined by the implementation of emergency measures.[xli]

As such, ST, which depends heavily on the social ontology of political discourses and practices, asserts that the “enunciation of security itself creates a new social order wherein ‘normal politics’ is bracketed.”[xlii] In essence, the unexpected and urgent nature of existential threats combined with the time pressure created by the desire for security generates a demand for swift responses, which involve bypassing the typically slower democratic processes or temporarily disregarding legal norms.[xliii]

Given what has been discussed, securitization can be seen as a process of truth production, behind which there are relations of power and interest.[xliv] Based on CS, security can be conceptualized as an intersubjective process referring to the social construction of threats by actors, through discourse, to obtain advantageous political outcomes such as legitimacy or support.

Analyzing the Essential Units of Securitization: Illuminating the Actors and Process

In an empirical study analyzing the discursive construction of existential threats, some key questions need to be addressed initially. These involve the designation of the securitizing actor (who talks about security), the referent object of security (who or what is to be secured), the functional actor, if any, and the audience (who will adopt the speech act, thus legitimizing the breaking of the established norms). Often, the securitizing actor and the referent object of security are different entities; the securitizing actor speaks security on behalf of a specific threatened entity, e.g., the state on behalf of its citizens.[xlv] Functional actors, on the other hand, are units that cannot independently produce security meanings but instead serve to interpret existing securitization processes. Finally, it is important to examine who the addressees of the securitization move are and how they react to it. If the audience adopts the threat, the emergency measures that follow can be assessed. In this section of the study, these constitutive units of the securitization process are thoroughly discussed.

The securitizing actor and constructing threat: a rhetorical analysis of securitizing discourse

The securitizing actor is the first of the units, which, in a sense, forms the answer to the following question: “What really makes something a security problem?”[xlvi] These agents possess the capacity to construct (unreal) or confront (existing) a certain issue as an existential security threat by asserting a security claim.[xlvii]

While the CS refers to “governments, political leaders, bureaucratic elites, lobbies, and pressure groups” as securitizing agents,[xlviii] it theoretically recognizes the possibility of, according to all actors, the ability to securitize issues. Nevertheless, in practical terms, due to prevailing power structures in the field of security, specific actors—typically statesmen or state elites—are granted privileged positions in defining security threats. This is attributed to the state authorities’ possession of privileged access to information through their intelligence services or other similar means, giving them the authority to manipulate the acquired information in their interest.[xlix]

Put another way, “leaders” are the decisive securitizing actors, particularly in foreign policy contexts,[l] as they are the entities with the capacity to enact emergency measures, either by changing behaviors on their own or by instructing practitioners of securitization to do so.[li] As Wæver explicitly asserts, “by definition, something is a security problem when the elites declare it so.”[lii] In this case study, the former President of the U.S., Donald Trump, who wielded the most political power during his time in office,[liii] is recognized as the primary securitizing agent in the process.

Justifying the threat: the rationales behind Trump’s North Korea securitization

The process of securitization implies an attempt to construct meaning. It enables the creation of shared beliefs about the meaning of events, policies, and issues. The strategic aim of this political maneuver is to demonstrate reassuring meaning in a way that supports the justification of the actions chosen as a response and encourages the audience to remain supportive.[liv] The intention here is to provide support for the securitization process and neutralize the opposition, while the political instrument is to produce arguments for this purpose.

In this respect, President Trump employed various arguments to construct or confront the perception that “North Korea poses an existential threat.” The discourse analysis reveals that the former president relied on two main and several secondary justifications for securitizing Pyongyang. The main themes are synthesized under the headings “the regime’s inhumane treatment of its own people” and “the threat posed by nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles,” while other reasons that diverge from these two categories are examined under the sub-heading “Alternative Rationales.” Each of the three encompasses various sub-arguments within itself.

The brutality of Kim Jong Un’s regime

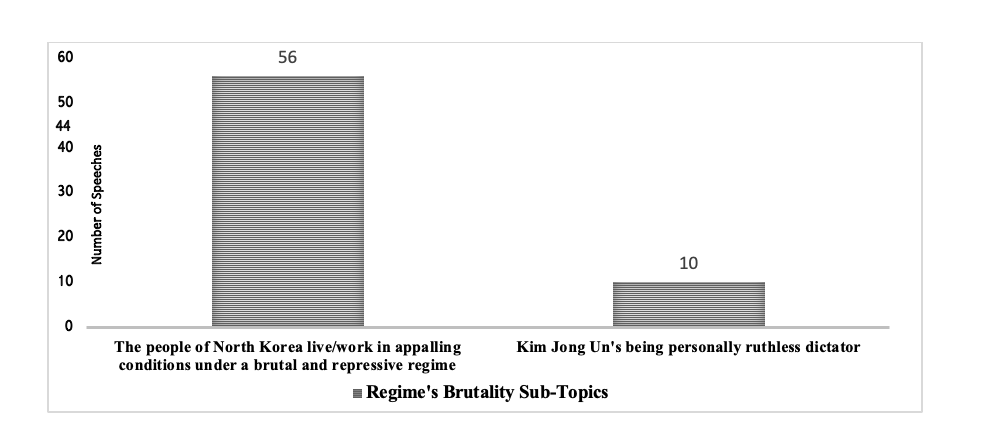

An examination of 44 statements unveils that a central reference supporting the securitization process is the “brutality exhibited by the Kim Jong Un regime.” Trump engaged in a securitizing move related to North Korea a total of 66 times using this argument. This reference point can be further divided into two subcategories, seen in Figure 1, as identified through the scrutiny of discourse patterns within the utterances.

Figure 1: Sentiments Regarding the Brutality of Kim Jong Un’s Regime Against Its Own Citizens

The first subtitle, “North Korean people live/work in terrible conditions under a brutal and oppressive regime,” entails President Trump’s recurrent characterization of the regime as morally reprehensible, oppressive towards its citizens, causing starvation, and subjecting laborers to inhumane working conditions. This depiction is reiterated 56 times across the 44 statements. One of these statements is given below:

President Trump: “…But no regime has oppressed its own citizens more totally or brutally than the cruel dictatorship in North Korea…”[lv]

The second subtitle, “Kim Jong Un is a dictator,” is related to the first subtitle, but pertains specifically to President Trump’s direct allegations against Kim Jong Un rather than encompassing the entire North Korean regime. The president explicitly labeled Kim as a dictator 10 times in the 44 statements. The following is one example of his statements directly targeting Kim Jong Un:

President Trump: “…We will together confront North Korea’s actions and prevent the North Korean dictator from threatening millions of innocent lives.”[lvi]

The recurrent emphasis on the oppressive actions of the dictatorial regime in Pyongyang towards its own people within securitization arguments led to a significant prominence of the North Korean people as the referent object. Thus, while the president referred twice to the threat to the U.S. nation and 18 times to the American homeland (as shown in Figure 4), he referred to the people of North Korea 24 times, underlining their centrality in the securitization discourse.

The president’s heightened emphasis on this argument, compared to others, may be attributed to the length and content of his speech in the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea.[lvii] This address, characterized by its securitizing nature, dealt extensively with the challenging situation within North Korea and critiqued the cruel tyranny of Kim Jong Un. The motivation behind this emphasis is thought to have stemmed, as previously mentioned, from a desire to impede a potential reunification. Observations indicate that Kim Jong Un interpreted Trump’s remarks in this manner.

Kim Jong Un: “Well aware of the will of the Korean nation to reunify their country, the U.S. must no longer cling to the scheme of whipping up national estrangement by inciting the anti-reunification forces in South Korea to confrontation with the fellow countrymen and war.”[lviii]

Additionally, President Trump’s persistent focus on this allegation, beyond the domestic and international public support, is thought to have been a quest by his search for legitimacy, especially in the minds of the South Korean people on issues that directly concern them, such as the redeployment of tactical nuclear weapons to South Korea. Notably, in line with the former president’s expectations, certain opposition parties and major media outlets in South Korea subsequently called for the redeployment of tactical nuclear weapons by the U.S.[lix] Moreover, a survey conducted by the Korea Society Opinion Institute revealed that 68.2% of participants believed that previously withdrawn U.S. tactical nuclear weapons should be redeployed to South Korea.[lx]

The nuclear and ballistic missile menace posed by the Kim Jong Un regime

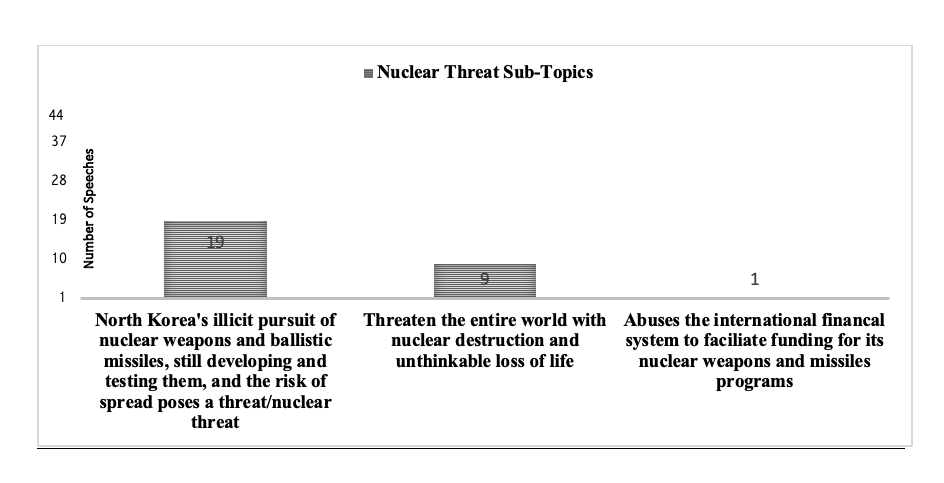

Within the justifications for securitization, it can be asserted that the primary reference point is North Korea’s nuclear activities and acquisitions. This priority is not numerical but contextual. In the entirety of the securitization corpus, these specific terms were directly used only 29 times, however, almost the entirety of the securitization discourse was in some way related to the country’s illicit nuclear weapons activities.

As depicted in Figure 2, this primary heading is divided into three subheadings. The first of these is summarized as “North Korea’s illegal pursuit, continued development, and testing of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles pose a threat.” 19 out of 29 references President Trump made fall under this subheading. Through this discourse, the president endeavored to explicitly demonstrate that none of the measures taken so far had prevented the Pyongyang regime, with its persistence in conducting provocative actions, from being a nuclear threat. Additionally, by drawing attention to the risk of nuclear proliferation, he highlighted the potential for rogue regimes or terrorist groups to acquire these weapons, posing a threat to other states in the absence of preventive measures:

President Trump: “The existence and risk of proliferation of weapons-usable fissile material on the Korean Peninsula and the actions and policies of the Government of North Korea continue to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”[lxi]

The second subtitle in this context consists of President Trump’s remarks, reiterated nine times, asserting that the regime’s “nuclear weapons and missile development threaten the entire world with unthinkable loss of life.” Framing all of humanity as the object of reference is interpreted as an indication of the former president’s intention to gain global support:

President Trump: “…All responsible nations must act now to ensure that North Korea’s rogue regime stops threatening the world with unthinkable loss of life… the North Korea problem, which is one of our truly great problems…”[lxii]

The last subtitle refers to “North Korea’s misuse of the international financial system to facilitate its nuclear weapons,”[lxiii] which was mentioned only once by Trump. Asserting that “all financial connections with Pyongyang merely contribute to its nuclear ambitions,” Trump sought to exert global pressure to sever ties with North Korea. Consequently, one could argue that he was laying the foundation for unprecedented financial sanctions against the Pyongyang regime, intending to compel Kim Jong Un towards a resolution aligning with his own interests.

Figure 2: Sentiments Regarding the Threat of Nuclear Weapons and Ballistic Missiles

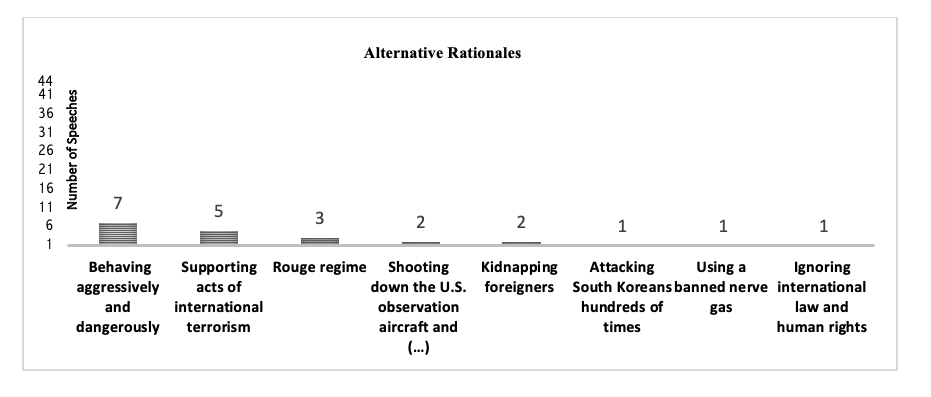

Alternative rationales

Beyond the two primary categories outlined, President Trump also utilized additional justifications. These secondary reasons encompassed the regime’s escalating aggression, characterized as increasingly perilous and rogue given its defiance of international law, incidents of kidnapping foreigners, including children, history of hundreds of attacks on South Koreans, the downing of a U.S. surveillance plane, causing casualties among its soldiers, engaging in the torture of captured soldiers, and the alleged use of a banned nerve agent in the killing of Kim’s own brother. One of these justifications was Trump’s claim of “endorsement of international terrorism,” which he used 5 times in his remarks, and which was put into practice with the successful reinstatement of Pyongyang on the list of “state sponsors of terrorism,” from which the country had been removed in 2008.[lxiv] The following are examples of the discourse in which these subordinate justifications take place.

President Trump: “…North Korea has repeatedly supported acts of international terrorism, including assassinations on foreign soil.”[lxv]

President Trump: “…We were all witness to the regime’s deadly abuse when an innocent American college student, Otto Warmbier, was returned to America only to die a few days later. We saw it in the assassination of the dictator’s brother using banned nerve agents in an international airport. We know it kidnapped a sweet 13-year-old Japanese girl from a beach in her own country to enslave her as a language tutor for North Korea’s spies.”[lxvi]

The prevalence of these alternative arguments in the former president’s discourse is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Alternative Reference Points and Sub-Topics

Assessing the compatibility of securitization discourse with facilitating conditions

The CS posits the existence of three facilitating conditions for securitization. These conditions, one internal and two external, refer to situations in which the speech act functions effectively, as opposed to situations in which it fails or is misused.[lxvii]

The internal condition refers to “the demand internal to the speech act of following the grammar of security.”[lxviii] This includes the construction of a narrative consisting of an existential threat, a critical juncture with no possibility of reversal, or a possible way out. As discernible from the following remarks, one can argue that Trump resorted to a very effective language of securitization that emphasized urgency, the magnitude of the threat, and the need for emergency action.

President Trump: “It is our responsibility and our duty to confront this danger (North Korea)[lxix] together…because the longer we wait, the greater the danger grows, and the fewer the options become.”[lxx]

President Trump: “We will together confront North Korea’s actions… He is indeed threatening millions and millions of lives so needlessly… North Korea is a worldwide threat that requires worldwide action. It’s time to act with urgency and with great determination...”[lxxi]

Moreover, after scrutinizing the former president’s security statements, it has been determined that he characterized North Korea as a “security problem” 38 times by employing expressions such as, “an urgent national security threat,” “top foreign policy priority,” “extraordinary threat,” “our single biggest problem,” “worldwide threat,” “major world problem,” “critical threats,” “real threat to the world,” “clear threat,” “major threat,” and “very important problem.” This preferred labeling accentuated the gravity of the situation and the necessity of taking immediate action to address this looming threat.

The external dimension of a speech act encompasses two basic conditions, the first of which refers to whether the securitizer is in a position of power to construct, present, or address the threat. [lxxii] Buzan et al. argue that there is a distinct clarity in the identification of securitizing actors within the political sector, as opposed to other sectors: “States by definition have authoritative leaders...”[lxxiii] Wæver underscores that analysts tend to highlight leaders as prominent securitizing actors in macro-level analyses.[lxxiv] In this case, President Trump appears to have possessed the necessary social capital—consisting of legitimacy, authoritative standing, and the ability to mobilize the audience and undertake extraordinary actions[lxxv]—to initiate the process of securitization. This aligns with the second condition outlined in the theory.

The last condition specified by the CS is that threats selected from issues that are embedded in the collective memory or that easily resonate with the public conscience, such as “tanks or hostile sentiments,” would enhance the securitization process.[lxxvi]

In this regard, a study conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has been consulted to assess the material context affecting the process. The findings lay bare that Kim Jong Un portrays a leadership image that is more aggressive both discursively and operationally compared to his predecessors. Thus, while a total of 78 provocative acts were carried out in North Korea (1995-2011), Kim Jong Un conducted 70 ballistic missile and three nuclear tests between January 2012 and November 2016 alone.[lxxviii] This number reached a historic high in terms of provocation, with 25 actions, including 24 ballistic missiles and one nuclear test, occurring within the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency, and over 100 missile tests throughout the four years, despite the serious attempts at reconciliation.[lxxix]

Moreover, the ballistic missile test conducted in July 2017 would have been able to cover 10,400 km and extended North Korea’s nuclear strike range to include Los Angeles, Denver, and Chicago. According to observers, the acquisition of these two technologies—the long-range ballistic missile and the thermo-nuclear warhead—has propelled North Korea to a more advanced stage in terms of reaching the U.S. mainland.[lxxx]

Furthermore, the belligerent stance in practice has been substantiated rhetorically through Kim Jong Un’s threat-laden discourse:

Kim Jong Un: “…The entire U.S. is within range of our nuclear weapons…a nuclear button is always on my desk…”[lxxxi]

All the threatening actions undertaken by Pyongyang, which is estimated to possess 40 to 50 warheads,[lxxxii] fulfill the third facilitating condition for securitization by way of expressing hostile sentiments. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to highlight that President Trump frequently referred to the objective conditions associated with North Korea’s expanding nuclear capabilities, recurrent nuclear and missile tests, and the potential reach of missiles to the homeland. For example:

President Trump: “… North Korea’s reckless pursuit of nuclear missiles could very soon threaten our homeland. We are waging a campaign of maximum pressure to prevent that from ever happening…”[lxxxiii]

President Trump: “… In 2009, the United States again offered to negotiate with North Korea. The regime answered by sinking the South Korean navy ship Cheonan, killing 46 sailors…To this day, it continues to launch missiles over the sovereign territory of Japan and all other neighbors, test nuclear devices, and develop ICBMs to threaten the United States itself…. We will not allow American cities to be threatened with destruction… We will not be intimidated. And we will not let the worst atrocities in history be repeated here on this ground we fought and died so hard to secure…”[lxxxiv]

This emphasis served as a facilitating factor that strengthened the former president’s hand in decision-making and implementation processes.

Indeed, North Korea’s imprudent pursuit of nuclear weapons and its achievements in 2017 and 2018 led to increased fragility and instability on a global scale. Concurrently, a noteworthy development was the reevaluation of support extended to North Korea by close allies, notably China and Russia, and the adoption of a stronger stance on sanctions, reflecting a discernible shift in geopolitical dynamics.

The referent objects of security

The referent object, which is perceived to be existentially threatened and for which protection is promised via securitization moves, is the other unit of the process. The CS has argued that three different levels of analysis can be employed to describe the referent object of security: micro (individuals or small-scale groups), middle (limited communities such as states),[lxxxv] and macro (e.g. universal ideologies or primary institutions of international society).[lxxxvi]

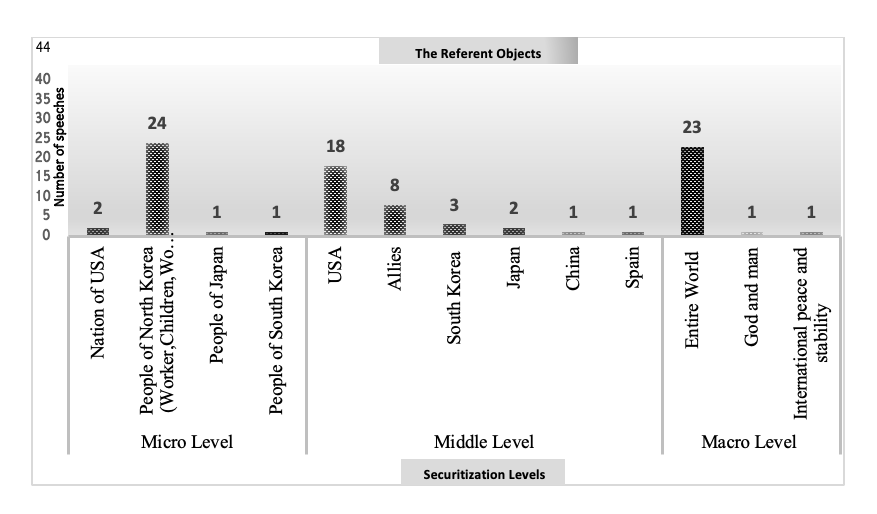

Figure 4: Scatterplot depicting the frequency with which President Trump referred to each referent object at the micro, middle, and macro levels across his 44 securitization statements

In his statements during the specified time frame, President Trump asserted at the micro-level that referent objects such as “our nation,” “the people of North Korea,” “the people of Japan,” and “the people of South Korea” were under threat. As evidenced by Figure 4, “the people of North Korea” was the most frequent referent object invoked by the president. For example:

President Trump: “…100,000 North Koreans suffer in gulags…and enduring starvation... One Korea in which the people took control of their lives…and chose a future of freedom…and incredible achievement…another Korea in which leaders imprison their people under the banner of tyranny…oppression…”[lxxxvii]

One underlying motivation for this emphasis could be an effort to draw the international community’s attention more effectively to the normative issues faced by North Koreans. Another could be the desire to induce caution among the people of South Korea to hinder a potential inter-Korean unification. Moreover, the scenario that Kim Jong Un, characterized as a tyrant, could deprive the South Koreans of the gains they have made to date, may have been reflecting a strategic approach going beyond mere caution and aiming to adversely influence the South Korean public’s attitudes towards the prospect of reunification.

An analysis of Trump’s discourse reveals that the former president alluded to referent objects at the middle level 33 times. These referents included “the USA,” “allies,” “South Korea,” “Japan,” “China,” and “Spain.” For example:

President Trump: “…it continues to launch missiles over the sovereign territory of Japan and all other neighbors…and develop ICBMs to threaten the United States itself.”[lxxxviii]

President Trump asserted 25 times that macro-level referent objects, such as “the whole world,” “God,” “humanity,” and “international peace and stability,” were under existential threat:

President Trump: “This is a real threat to the world…North Korea is a big world problem…”[lxxxix]

The functional actors

Within the complex dynamics of securitization processes, actors exist who, while not directly articulating security claims, possess the capacity to significantly influence the trajectory and outcomes of these processes. These so-called “functional actors” operate as influential secondary players with the capacity to influence and steer the dynamics in their sectors positively or negatively. The category of functional actors encompasses a diverse array of societal entities, ranging from individuals situated within the public sphere, such as ordinary citizens and media professionals, to specialized knowledge producers, notably academics and other knowledge-based experts. [xc]

In this case study, the media was viewed as the “gatekeeper”[xci] with the power to decide what information becomes public knowledge. As such, its position is indisputably stronger than that of other functional actors.[xcii] Given this, the examination of media data involved the analysis of online editions from two prominent newspapers[xciii] in the U.S., namely The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) and USA Today. During the focus period of January 20, 2017, to June 12, 2018, a search query specifically targeting “North Korea” and “Kim Jong Un” revealed that there were approximately 90 relevant news headlines in the WSJ, and nearly 300 news headlines in USA Today.

Expressions such as “nuclear threat,” “weapons,” “atrocity,” “risk,” “crisis,” “great/top threat,” “big problem,” “warfare,” “attack,” “military action,” “terror” or “sponsor of terrorism,” “the ability to reach the U.S./mainland/homeland with its missiles,” “detention or kidnapping of American citizens,” and “torture” as associated with North Korea or Kim Jong Un were perceived to significantly shape the audience’s perception of the DPRK. These selected headlines contributed to the construction of a narrative wherein Pyongyang was portrayed as an existential threat not only to the nation, but also to individuals directly.

Indeed, by adopting certain expressions, manipulating content, or handling the issue in a particular way, the media can ensure that any phenomenon is perceived as a challenge. They can direct public attention to certain issues by prioritizing or emphasizing them, and media outlets can either protect the image of a securitizer or undermine the legitimacy of their policies by damaging that image, ultimately mobilizing the public against a particular threat or policy through their commentary. Moreover, they can create fear and panic in the public through aggressive or over-dramatized coverage that supports the actions taken by securitizing actors.[xciv]

The portrayal of a threat, amplified by the media,[xcv] serves to create a dynamic atmosphere of panic. This ambiance—precisely as the CS articulates—provided President Trump with a platform to legitimize various measures against perceived malevolence and, at the same time, to suppress potential dissent.[xcvi]

The securitization audience and findings on “acceptance”

The final unit is the audience, which is the recipient of the securitizing speech act. The securitization audience can be outlined as the individual(s) or group(s) possessing the capability to authorize the narrative presented by the securitizer and legitimize the handling of the issue through security practices.[xcvii]

The indispensable precondition for any securitization to exist is the acceptance of the threat designation by a significant audience. However, the Copenhagen version of the ST does not provide a detailed roadmap for how the impact of the audience on the outcomes of securitization could emerge in an empirical analysis.[xcviii] Stated differently, how to measure the responses (endorsement or dissent) of the relevant audiences is an area of uncertainty in the CS.

However, Côté has argued that this vagueness can be removed, particularly in democratic contexts, through informal data sources such as opinion polls or more formalized data, including votes on specific issues within legislative bodies (e.g., Congress or Parliament) or broader electoral outcomes, which can serve to elucidate the extent of trust vested in a securitizing actor by the audience. In such instances, the direction in which the voting or poll results exhibit a greater skewness serves as an indicator of the audience’s approval or disapproval.[xcix]

On the other hand, Balzacq underscores the necessity for analyzing the support extended to the securitizer by the audience through two distinct stages: moral support originating from the public and formal support emanating from institutions such as parliament and the senate.[c] In this case, the argument asserts that the U.S. public opinion, with its ability to influence anticipated outcomes through dissent, serves as the primary target audience that has morally supported the securitization process.

In this context, a comparative analysis of poll results from the Pew Research Center, CNN, and Gallup during the pre-securitization and securitization periods has been employed to assess how the public opinion responded to President Trump’s securitizing move and its subsequent impact on political practices. Concerning the “size and significance” of audience support, O’Reilly’s concept of “critical mass” has been invoked. As he articulates, a particular securitization occurs “when the securitizing actor has convinced enough of the right people that someone or something constitutes a legitimate security threat.”[ci] The term “enough” is generally considered to correspond to more than half of the recipients.

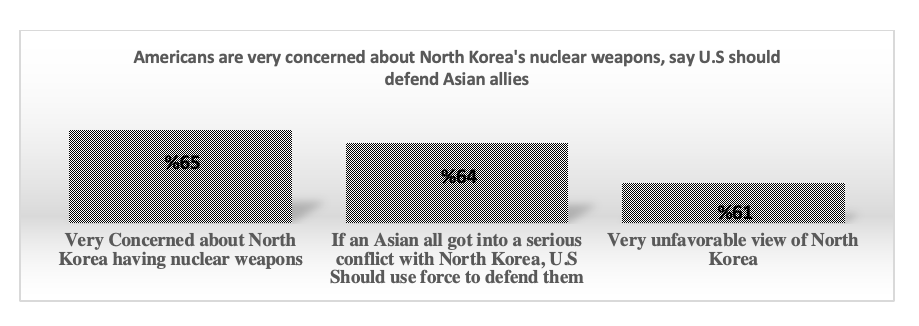

To illustrate this point, Table 1 delineates the findings from a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center on April 5, 2017. As evidenced, roughly 65% of participants conveyed a level of apprehension categorized as “very concerned” regarding Pyongyang’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. Therefore, an inference can be drawn that approximately two-thirds of the surveyed American populace embraced the existential threat perception disseminated by Trump in the context of North Korea’s nuclear pursuits.

Table 1: Pew Research Center/Global Attitudes Survey Results, 5 April 2017[cii]

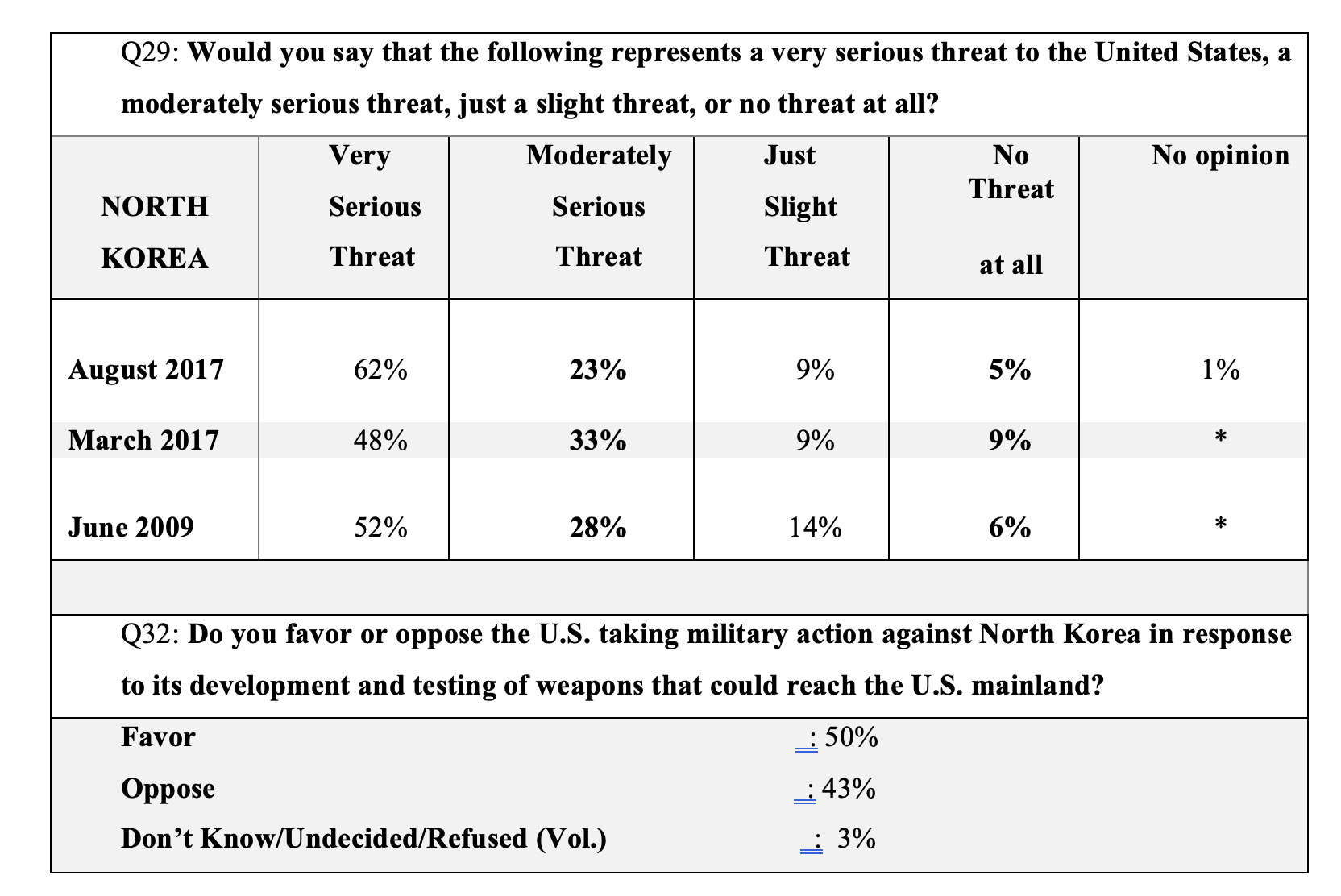

Nevertheless, considering the potential limitations of reliance on a solitary survey, the study incorporated findings from a CNN-conducted survey between August 3 and 6, 2017, to obtain a more comprehensive result.[ciii] As delineated in Table 2, a notable majority of Americans (62%) perceived Pyongyang as a “very serious threat” to the U.S. Notably, despite the survey being conducted just before North Korea’s sixth nuclear test, these findings indicate a 14% increase in the perceived threat compared to a similar survey conducted in March. According to CNN, the level of concern regarding Pyongyang has reached its highest point in surveys conducted since 2000. This percentage surpasses even the recorded 52% following North Korea’s second nuclear test in June 2009, underscoring a heightened apprehension in the current context.

Table 2: CNN poll results, 3-6 August 2017[civ]

Drawing upon data obtained from surveys, it can be asserted that audience acceptance encompasses not only the security discourse, but also potential institutional ramifications of securitization or “extraordinary” policy responses, such as the suggested military operations against the identified threat by the securitizer. For instance, in the Pew survey, 64% of Americans expressed support for the idea that, in the event of a serious conflict, the U.S. should employ military force to protect its Asian allies against Pyongyang. A similar finding was obtained in a Gallup poll conducted in September 2017. In response to the question, “If the U.S. does not achieve its goals regarding North Korea through economic and diplomatic efforts, would you support or oppose the use of military action against North Korea?” 58% of the American public expressed support. This signifies that most Americans endorsed military action against Pyongyang, particularly as a last resort.[cv]

The findings presented above provide important insights into the moral support of the American public opinion for President Trump’s securitization process. However, according to Balzcaq, while moral support is necessary in theory, it is not sufficient in practice.[cvi] Indeed, frequently, it is the formal resolution by an institution (e.g., in the form of a ballot by a parliament or the Security Council) that obligates the government to adopt a specific policy. Thus, another addressee of President Trump’s securitization discourse was the U.S. Congress.

The following is an extract from remarks by President Trump’s 2018 State of the Union Address.

President Trump: “... North Korea’s reckless pursuit of nuclear missiles could very soon threaten our homeland...I will not repeat the mistakes of past administrations that got us into this very dangerous position. We need only look at the depraved character of the North Korean regime to understand the nature of the nuclear threat it could pose to America and to our allies.”[cvii]

Securitizing agents resort to discourses asserting the insecurity of the national territory to procure not only public approval, but also the necessary official backing. After all, members of Congress are themselves constituents of the endangered referent object, the homeland. Hence, the understanding that they, too, are subject to a potential threat is construed as a facilitating factor prompting them to undertake action. Despite occasional challenges encountered in securing legislative support during the actualization of rhetorical securitizations by President Trump, the necessary support was observed to be obtained from Congress.

For instance, the presidentially-led initiative to designate North Korea as a “State Sponsor of Terrorism” and to impose significant sanctions[cviii] received approval from Congress by a vote of 394 to 1.[cix] In the process, Congress made it clear that North Korea satisfies the criteria for designation as a state sponsor of terrorism due to its failure to verifiably dismantle its nuclear weapons program as committed to in 2008 and its continued support for international terrorism activities.[cx]

In the pursuit of formal support, another audience requiring persuasion is the UN, perceived as the embodiment of the international community. The international community’s reaction to President Trump’s securitizing move can be elucidated by analyzing the co-decision-making processes within this organization and considering aspects such as unanimity or majority voting. By analyzing the corpus of 44 statements constituting the securitization discourse by the President, it is observed that Trump sought to attract the attention of the international community not only by raising normative issues, but also by frequently using rhetoric asserting that North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missiles posed a threat not only to the U.S. and its allies, but to the entire world.

According to the President, the world must “unite against the nuclear menace posed by the North Korean regime, a threat that has increased steadily through many administrations and now requires urgent action.”[cxi] Otherwise, “this depraved regime”[cxii] would persist in “threatening the world with nuclear devastation”[cxiii] or “unimaginable loss of life.”[cxiv]

The following is an extract from President Trump’s remarks to the UNGA:

President Trump: “It is an outrage that some nations would not only trade with such a regime, but would arm, supply, and financially support a country that imperils the world with nuclear conflict. No nation on earth has an interest in seeing this band of criminals arm itself with nuclear weapons and missiles… That’s what the UN is all about; that’s what the United Nations is for. Let’s see how they do. It is time for all nations to work together to isolate the Kim regime until it ceases its hostile behavior.”[cxv]

During this period, North Korea’s gross human rights violations were placed on the official agenda of the UNSC four times “as a threat to international peace and security.” In December 2017, the UNGA adopted a resolution condemning North Korea’s human rights violations without a vote.[cxvi] But more importantly, in terms of practical consequences, the UNSC, led by Washington, passed several resolutions against Pyongyang, including Resolutions 2356, 2371, 2375, and 2397.[cxvii] It is noteworthy that all these resolutions were passed unanimously, even with the support of North Korea’s key allies, China and Russia. This indicates that President Trump’s securitizing move received unprecedented international support. Trump even expressed his gratitude to Russia and China while also urging all nations to do more.

President Trump: “It is time for North Korea to realize that the denuclearization is its only acceptable future. The UNSC recently held two unanimous 15-0 votes adopting hard-hitting resolutions against North Korea, and I want to thank China and Russia for joining the vote to impose sanctions, along with all of the other members of the UNSC. Thank you to all involved…It is time for all nations to work together to isolate the Kim regime until it ceases its hostile behavior.”[cxviii]

Operationalizing of Securitization Discourse: The Taking of Extraordinary Measures

The execution of emergency measures, representing the translation of securitization discourse into practice, is another crucial aspect examined in the study. As noted above, securitization does not simply occur when an actor labels an issue as an existential threat; this is merely a securitizing move. Instead, “the existence of securitization” only emerges at the point where an engaged audience accepts the speech act. Once an issue is acquired by the audience, the securitizer is able to take extraordinary measures to deal with the threat, potentially transcending established norms and rules.

In this sense, the exceptional measures or breaking of rules are determinants not of “the existence of securitization,” but of “its success.”[cxix] As Buzan et al. put it, a successful securitization has three components: “existential threats, emergency actions, and the effects on inter-unit relations through rule breaking.”[cxx]

In this framework, considering the political outcomes arising from President Trump’s securitization process reveals the implementation of various measures that can be characterized as legitimizing the actualization of extraordinariness. Notably, the expeditious deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD)[cxxi] systems to South Korea,[cxxii] justified as a response to the escalating North Korean threat, and the dispatch of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson after the latest missile test by North Korea to the region[cxxiii] may be considered as extraordinary instruments employed in support of the securitizing move of the former U.S. President. Moreover, the initiatives taken by the Trump administration, specifically the decision to ban citizens from traveling to North Korea[cxxiv] under the pretext of security concerns, constituted an infringement upon individuals’ freedom of movement. The decision “suspending the entry of ‘immigrant and nonimmigrant’ travelers from North Korea to the U.S.,”[cxxv] which was taken without any substantiated evidence of individual wrongdoing or concrete proof of harm to American interests posed by each North Korean citizen, is also perceived as an illustrative instance of executive orders deviating from established norms.

Concluding Remarks: Determination of the Securitization’s Effectiveness

Wæver argues that security is a “speech act” in which a state agent moves a particular issue from the political realm to a specific sphere and thereby claims a special right to use whatever means are necessary to prevent it.[cxxvi] In this regard, ST, which is based on the performativity of language, derives its power source from the discourses that are used by the securitizing actor and are appropriate for the “facilitating conditions.”

However, a particular securitization only exists when the audience accepts it and is fulfilled by enacting emergency measures. If there is no indication of such acceptance, one can only speak of a securitizing move, not of an entity that is being securitized. Securitization can therefore be seen as a sequence that begins with a deliberate political decision and culminates in an intersubjective process.

Based on the theoretical framework provided, this study has been conducted to examine if the security discourse employed by former U.S. President Donald Trump, spanning the period from January 20, 2017, to June 12, 2018, with the objective of framing North Korea as a security threat, remained a securitizing move or turned into an effective practice of securitization. In this context, a securitization corpus comprising 44 statements of the former president was identified. Subsequently, a comprehensive examination of this corpus was conducted, employing discourse and content analysis methodologies. This analysis revealed instances of securitizing moves by the former president at the micro, middle, and macro levels. Moreover, in the process of securitizing, Trump was noted to strategically invoke specific reference points such as the perceived brutality of the Kim Jong Un regime, the associated threats emanating from nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, as well as purported support for international terrorism. The utilization of these arguments appeared geared towards accruing distinct political advantages, notably in terms of securing legitimacy and garnering support.

Furthermore, the success of the former president’s security discourse, which was assessed to comply with the “facilitating conditions,” was evaluated using two parameters: the discursive and practical effects of the securitizing move. The term “discursive effect” refers to the acceptance of threat narratives by a certain audience. In this context, the principal pertinent audiences—namely, the U.S. public opinion, U.S. Congress, and the UN—embraced President Trump’s discourse on security, conceiving North Korea as a substantial threat necessitating immediate attention through both formal and informal mechanisms, including official voting procedures and public opinion polls.

The discursive effect legitimizes the practical effects, which may require the enactment of emergency security measures. In scrutinizing President Trump’s responses to the threat, it is evident that he implemented numerous security practices beyond the normal functions of politics. Actions such as the deployment of an aircraft carrier to the region, the suspension of the constitutionally protected freedom of movement, and the restriction of North Koreans’ freedom to work through national and international sanctions are just a few examples of unconventional measures that were taken.

In conclusion, this study elucidates that President Trump, by framing the North Korean regime as an existential threat through security rhetoric, successfully disseminated this narrative to the audience, implemented policy changes by actualizing the measures, and effectively shifted the issue from the political realm to the realm of security, which subsequently enabled and even legitimized emergency measures.

Notes

[i] The acronym “ST” used in this study refers to the classical Copenhagen version of securitization theory. Contemporary securitization studies, moreover, consist of several competing approaches to securitization, each of which has evolved, elaborated upon, and, in some cases, elucidated critical elements of the classic CS version. These include sociological and philosophical perspectives, linguistic/discursive analyses versus practice-oriented methodologies, and explanatory versus constitutive (or normative) approaches. On these different characterizations, see Thierry Balzacq, “A Theory of Securitization: Origins, Core Assumptions, and Variants,” in Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, ed. Thierry Balzacq, (London: Routledge, 2011), 1–30.

[ii] The term existential threat is defined as “catastrophic hazards that severely imperil human flourishing and survival.” Toni Erskine, “Existential Threats, Shared Responsibility, and Australia’s Role in Coalitions of the Obligated,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 76, no 2 (2022): 130.

[iii] Mark Salter, “When Securitization Fails: The Hard Case of Counter-terrorism Programs,” in Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, ed. Thierry Balzacq (London: Routledge, 2010), 116–32.

[iv] Barry Buzan et al., Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998), 27.

[v] President Obama’s policy approach toward North Korea, termed “strategic patience,” was rooted in a conviction of maintaining the existing status quo despite its suboptimal nature. This approach reflected a belief that the risks associated with immediate action were potentially more detrimental than the challenges posed by the then current situation. See, “Nuclear Negotiations with North Korea,” CRS Report: R45033, May 4, 2021, accessed date April 2, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45033.

[vi] “Trump declares ‘patience is over’ with North Korea,” The Guardian, June 1, 2017, accessed date July 5, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/01/donald-trump-declares-patience-is-over-with-north-korea.

[vii] “Nuclear Negotiations.”

[viii] “Leaders Brief Congress on Review of North Korea Policy,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 26, 2017, accessed date May 21, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1164057/leaders-brief-congress-on-review-of-north-korea-policy/.

[ix] “Nuclear Negotiations.”

[x] For more detail, see Kathleen J. McInnis, “The North Korean Nuclear Challenge: Military Options and Issues for Congress,” CRS Report R44994, November 6, 2017, accessed date October 8, 2021. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/nuke/R44994.pdf.

[xi] “Trump warns N Korea that US military is ‘locked and loaded,’” BBC, August 11, 2017, accessed date October 8, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-40901746

[xii] “Remarks by President Trump to the 72nd Session of the United Nations General Assembly,” White House Archives, September 19, 2017, accessed date January 23, 2022. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefstrfings-statements/remarks-president-trump-72nd-session-united-nations-general-assembly/.

[xiii] Anna Fifield, “Kim Jong Un calls Trump a ‘mentally deranged U.S. dotard,’” The Washington Post, September 21, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/09/21/north-korean-leader-to-trump-i-will-surely-and-definitely-tame-the-mentally-deranged-u-s-dotard-with-fire/.

[xiv] Donald Trump, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: White House 2017), accessed date June 28, 2021. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

[xv] “US-North Korea summit ‘an important milestone’ towards denuclearization, says Guterres,” Soualiga Newsday, June 12, 2018, accessed date December 14, 2021. https://www.soualiganewsday.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=20154:us-north-korea-summit-%E2%80%98an-important-milestone%E2%80%99-towards-denuclearization,-says-guterres&Itemid=519.

[xvi] Buzan et al., 4.

[xvii] “The Trump Twitter Archive,” Trump Twitter Archive V2, June 12, 2018, accessed date March 28, 2021. https://www.thetrumparchive.com.

[xviii] Emphasis is the authors’; “Trump Claims Has ‘Largely Solved’ North Korean Nuclear Crisis,” RFL/RL, June 15, 2018, accessed date March 18, 2021. https://www.rferl.org/a/us-trump-claims-has-largely-solved-north-korean-nuclear-crisis/29292309.html.

[xix] Ole Wæver, “Securitization and Desecuritization,” in On Security, ed. Ronnie Lipschutz (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 46-86; Buzan et al., Security, 27.

[xx] Major journals have even published special issues discussing the strengths and weaknesses of the concept of securitization as follows: Security Dialogue, 2011; International Relations, 2015; Polity, 2019; Thierry Balzacq, “Securitization Theory: Past, Present, and Future,” Polity 51, no 2 (2019): 331–348.

[xxi] Howell and Richter-Montpetit contend that eurocentrism encompasses the notions that: (1) ‘Europe’ or ‘the West’ is ontologically distinctive; (2) European development was endogenous; and (3) European cultural and political achievements were subsequently diffused across the world. However, ST is structured not solely by Eurocentrism but also by civilizationism, methodological whiteness, and anti-Black racism. See, Alison Howell and Melenie Richter-Montpetit, “Is Securitization Theory Racist? Civilizationism, Methodological Whiteness, and Anti-black Thought in the Copenhagen School,” Security Dialogue 51, no 1 (2020): 3. For a more detailed discussion of the critique of Eurocentrism in the CS, see also Claire Wilkinson, “The Copenhagen School on Tour in Kyrgyzstan: Is Securitization Theory Useable Outside Europe,” Security Dialogue 38, no 1 (2007): 5-25.

[xxii] Pınar Bilgin, “The Politics of Studying Securitization? The Copenhagen School in Turkey,” Security Dialogue, 42 (2011): 399; Tayyar Arı, ed. Critical Theories in International Relations: Identity and Security Dilemma (London: Lexington Books, 2023).

[xxiii] Philippe Bourbeau, The Securitization of Migration: A Study of Movement and Order (London: Routledge, 2011).

[xxiv] Sabrina B. Arias, “Who Securitizes? Climate Change Discourse in the United Nations,” International Studies Quarterly 66, no 2 (2022):1-52.

[xxv] Sefa Secen, “Explaining the Politics of Security: Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Lebanon,” Journal of Global Security Studies 6, no 3 (2021): 1-21.

[xxvi] Christian Kaunert et al., “Securitization of COVID-19 as a Security Norm: WHO Norm Entrepreneurship and Norm Cascading,” Social Sciences 11, no 7 (2022): 1-19.

[xxvii] Linus Hagström and Magnus Lundström, “Overcoming US-North Korean Enmity: Lessons from an Eclectic IR Approach,” The International Spectator 54, no. 4 (2019): 94-108; Matteo Dian, “Trump’s Mixed Signals toward North Korea and US-led Alliances in East Asia,” The International Spectator 53, no 4 (2018): 112-128.

[xxviii] Hazel Smith, “Bad, Mad, Sad or Rational Actor? Why the ‘Securitization’ Paradigm Makes for Poor Policy Analysis of North Korea,” International Affairs 76, no 3 (2000): 593-617.

[xxix] For an original study highlighting the importance of methodological tools and approaches in international relations, see also Ersel Aydınlı, ed., Uluslararası İlişkilerde Metodoloji (İstanbul: Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2022).

[xxx] Buzan et al., Security, 176.

[xxxi] Ole Wæver, “Identity, Communities and Foreign Policy: Discourse Analysis as a Foreign Policy Theory,” in European Integration and National Identity: The Challenge of the Nordic State, eds. Lene Hansen and Ole Wæver (London: Routledge, 2002), 26-27.

[xxxii] Donald Trump’s Twitter account was suspended from 8 January 2021 to 20 November 2022. The Trump Twitter Archive (https://www.thetrumparchive.com), an online database of Trump’s tweets from 2013 onwards, was referenced in this analysis.

[xxxiii] The public statements and other official sources were sourced from the following websites: “The Trump White House Archive,” White House Archives, accessed date January 12, 2020. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov; “Donald Trump,” American Presidency Project, accessed date September 14, 2024.

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/donald-j-trump; Barack Obama, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: White House, 2015), accessed date April 30, 2021. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/

default/files/docs/2015_national_security_strategy_2.pdf; “Resolutions,” United Nations Security Council, accessed date July 25, 2021. https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/resolutions.

[xxxiv] Buzan et al., Security, 1, 21.

[xxxv] Tayyar Arı, Uluslararası İlişkiler Teorileri (Bursa: Aktüel, 2021), 78-97.

[xxxvi] For a comparative analysis of neoclassical realism and the CS, see also Sinem Akgül-Açıkmeşe, “Algı mı, Söylem mi? Kopenhag Okulu ve Yeni Klasik Gerçekçilikte Güvenlik Tehditleri,” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 8, no 30 (2011): 43-73.

[xxxvii] Arı, Uluslararası,106.

[xxxviii] Norrin M. Ripsman et al., “Neoclassical Realist Intervening Variables,” in Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics, eds. Norrin M. Ripsman et al., (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016), 61-63.

[xxxix] Ole Wæver and Barry Buzan, “Racism and Responsibility – The Critical Limits of Deepfake Methodology in Security Studies: A Reply to Howell and Richter Montpetit,” Security Dialogue l, no 51(4) (2020): 391.

[xl] These stages are commonly referred to as “the grammar of security,” a somewhat grandiose term. See, Rita Floyd, “Securitization theories: Big Picture Theorising vs. 1:1 Mapping,” paper presented at ISA Annual Convention, Montréal: (Slot Code: SC32) Innovations in Securitization Studies, 2023.

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Thierry Balzacq, “The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience, and Context,” European Journal of International Relations 11, no 2 (2005): 171; Illustratively, in response to the World Health Organization’s designation of COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in January 2020, various nations, regardless of their democratic or non-democratic governance, pursued unconventional measures to combat the pandemic. These measures included reallocating state budgets, implementing large-scale quarantines, imposing travel restrictions, and instituting national lockdowns. See, Jessica Kirk and Matt McDonald, “The Politics of Exceptionalism: Securitization and COVID-19,” Global Studies Quarterly 1, no 3 (2021):1-12.

[xliii] Tine Hanrieder and Christian Kreuder-Sonnen, “WHO Decides on the Exception? Securitization and Emergency Governance in Global Health,” Security Dialogue 45, no 4 (2014): 335.

[xliv] Başar Baysal, “20 Years of Securitization: Strengths, Limitations and A New Dual Framework,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 17, no 67 (2020): 11.

[xlv] Rita Floyd and Stuart Croft, “European Non-Traditional Security Theory: From Theory to Practice,” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 3, no 2 (2011): 152–179.

[xlvi] Wæver, “Securitization,” 4.

[xlvii] Sinem Akgul-Acikmese, “EU Conditionality and Desecuritization nexus in Turkey,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 13, no 3 (2013): 306.

[xlviii] Buzan et al., Security, 31-32, 40.

[xlix] Ciaran O’Reilly, “Primetime Patriotism: News Media and the Securitization of Iraq,” Journal of Politics and Law 1, no 3 (2008): 69.

[l] Alexander Schotthöfer, “Individuals in Securitization: Explaining US Presidents’ Choice to (De)Securitize North Korea,” Foreign Policy Analysis 20, no 3 (2024): 4.

[li] Rita Floyd, “Securitization and the Function of Functional Actors,” Critical Studies on Security 9, no 2 (2021): 88.

[lii] Wæver, “Desecuritization,” 54.

[liii] It is worth noting that, unlike many issues in American foreign policy, there is no significant difference between Democrats and Republicans in their attitudes toward North Korea. See, Jacob Pouster, “Americans hold very negative views of North Korea amid nuclear tensions,” PEW Research, April 5, 2017, accessed date August 26, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/04/05/americans-hold-very-negative-views-of-north-korea-amid-nuclear-tensions/.

[liv] Kirk and McDonald, “The Politics of Exceptionalism,” 1-12.

[lv] “Remarks by President Trump in State of the Union Address,” White House Archives, January 30, 2018, accessed date October 26, 2022. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-state-union-address/.

[lvi] “Remarks by President Trump and President Moon of the Republic of Korea in Joint Press Conference | Seoul, Republic of Korea,” White House Archives, November 7, 2017, accessed date October 26, 2022. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-president-moon-republic-korea-joint-press-conference-seoul-republic-korea/.

[lvii] “Remarks by President Trump to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea,” White House Archives, December 11, 2017, accessed date May 23, 2021. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-national-assembly-republic-korea-seoul-republic-korea/.

[lviii] Kim Jong Un, “Kim Jong Un’s 2017 New Year's Address,” The National Committee on North Korea, January 2, 2017, accessed date April 3, 2021. https://www.ncnk.org/sites/default/files/KJU_2017_New_Years_Address.pdf.

[lix] “South Korea to bring back US tactical nuclear missiles?” DW, September 6, 2017, accessed date February 8, 2021. https://www.dw.com/en/south-korea-to-bring-back-us-tactical-nuclear-missiles/a-40377902.

[lx] Se Young Jang, “Do South Koreans Really Want U.S. Tactical Nukes Back on the Korean Peninsula?” National Interest, September 19, 2017, accessed date February 8, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/do-south-koreans-really-want-us-tactical-nukes-back-the-22379.

[lxi] “Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to North Korea,” White House Archives, June 21, 2017, accessed date May 22, 2021. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/continuation-national-emergency-respect-north-korea/.

[lxii] “United Nations General Assembly.”

[lxiii] “Remarks by President Trump, President Moon, and Prime Minister Abe,” White House Archives, September 21, 2017, accessed date May 21, 2021. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-president-moon-republic-korea-prime-minister-abe-japan-trilateral-meeting/.

[lxiv] “State Sponsors of Terrorism,” U.S. Department of State, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://www.state.gov/state-sponsors-of-terrorism/.

[lxv] “Remarks by President Trump Before Cabinet Meeting,” White House Archives, November 20, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-cabinet-meeting-2/.

[lxvi] “United Nations General Assembly.”

[lxvii] Buzan et al., Security, 32.

[lxviii] Wæver, “Securitization,” 15.

[lxix] Emphasis is the authors’.

[lxx] “Remarks by President Trump to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea.”

[lxxi] “Remarks by President Trump and President Moon.”

[lxxii] Ole Wæver, “The EU as a Security Actor – Reflections from a Pessimistic Constructivist on Post-sovereign Security Orders,” in International Relations Theory & European Integration: Power, Security, and Community, eds. Morten Kelstrup and Michael C. Williams, (London: Routledge, 2000), 252-253.

[lxxiii] Buzan et al., Security, 146.

[lxxiv] Wæver, “Taking,” 36.

[lxxv] Buzan et al., Security, 33.

[lxxvi] Ibid.

[lxxvii] Based on the date of the first documented North Korean provocation, the year 1958 was chosen. “Database: North Korean Provocation,” Beyond the Parallel, December 20, 2019, accessed date April 3, 2021. https://beyondparallel.csis.org/database-north-korean-provocations/.

[lxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxix] Lisa Collins, “25 Years of Negotiations and Provocations: North Korea and the U.S.,” Beyond the Parallel, accessed date April 3, 2021. https://beyondparallel.csis.org/25-years-of-negotiations-provocations/.

[lxxx] Sung-han Kim and Snyder Scott, “Denuclearizing North Korea: Time for Plan B,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 81.

[lxxxi] Bruce Harrison, “Kim Jong Un Highlights His ‘Nuclear Button,’ Offers Olympic Talks,” NBC News, January 2, 2018, accessed date April 3, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/north-korea/kim-says-north-korea-s-nuclear-weapons-will-prevent-war-n833781.

[lxxxii] Jon Herskovitz, “These Are the Nuclear Weapons North Korea Has as Fears Mount of Atomic Test,” Bloomberg, December 3, 2022, accessed date December 24, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-03/how-kim-jong-un-keeps-advancing-his-nuclear-program-quicktake.

[lxxxiii] “Remarks by President Trump in State of the Union Address.”

[lxxxiv] Jim Garamone, “Trump Warns North Korean Leader Not to Underestimate U.S.-South Korean Will,” U.S. Department of Defense, November 7, 2017, accessed date December 24, 2022. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1365790/trump-warns-north-korean-leader-not-to-underestimate-us-south-korean-will/.

[lxxxv] Buzan et al., Security, 36.

[lxxxvi] Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, “Macrosecuritization and Security Constellations: Reconsidering Scale in Securitization Theory,” Review of International Studies 35 no 2, (2009): 257.

[lxxxvii] “Remarks by President Trump to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea.”

[lxxxviii] “Trump Warns North Korean Leader Not to Underestimate U.S.-South Korean Will,” U.S. Department of Defense, November 7, 2017, accessed date May 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1365790/trump-warns-north-korean-leader-not-to-underestimate-us-south-korean-will/.

[lxxxix] “Remarks by President Trump at a Working Lunch with U.N. Security Council Ambassadors,” White House Archives, May 24, 2017, accessed date May 23, 2021. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-working-lunch-u-n-security-council-ambassadors/.

[xc] Floyd, “Securitization and the Function,” 89.

[xci] Ibid., 90.

[xcii] Ibid.

[xciii]“Top 10 U.S. Newspapers by Circulation,” Agilty PR, July 2022, accessed date December 23, 2023. https://www.agilitypr.com/resources/top-media-outlets/top-10-daily-american-newspapers/.

[xciv] Alberto Tagliaietra, “Media and Securitization: The Influence on Perception,” IAI Papers 21, no 34 (2021): 1-17.

[xcv] For example, “Guam residents shaken by ‘scary’ threats from North Korea,” USA Today, August 8, 2018, accessed date January 23, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/videos/news/world/2017/08/09/guam-residents-shaken-scary-threats-north-korea/104423744/.

[xcvi] The media persisted with this stance even after the Singapore Summit, which was seen as a critical step towards desecuritization, and was blasted by Trump as the country’s “biggest enemy” for its coverage of this historic summit. President Trump: “So funny to watch the Fake News, especially NBC and CNN. They are fighting hard to downplay the deal with North Korea…500 days ago, they would have begged for this deal—looked like war would break out.” See, Christal Hayes, “Trump blasts media as America’s ‘biggest enemy’ for North Korea coverage,” USA Today, June 13, 2008, accessed date January 25, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2018/06/13/donald-trump-blasts-media-americas-biggest-enemy-north-korea-coverage/697532002/.

[xcvii] Floyd, “Securitization and the Function,” 85.

[xcviii] Michael C. Williams, “The Continuing Evolution of Securitization Theory,” in Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, ed. Thierry Balzacq (London: Routledge, 2011), 212.

[xcix] Adam Côté, “Social Securitization Theory,” PhD diss., (University of Calgary, 2015).

[c] Balzacq, “The Three Faces of Securitization,” 8-9.

[ci] O’Reilly, “Primetime Patriotism,” 67.

[cii] Pouster, “Americans.”

[ciii] “CNN Pool (03 August-06 August 2017),” CNN, 2017, accessed date April 30, 2021. http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/2017/images/08/08/rel7b.-.north.korea.pdf.

[civ] Ibid.

[cv] Lydia Saad, “More Back U.S. Military Action vs. North Korea Than in 2003,” Gallup, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/219134/back-military-action-north-korea-2003.aspx.

[cvi] Balzacq, “The Three Faces of Securitization,” 9.

[cvii] “Remarks by President Trump in State of the Union Address.”

[cviii] This legislative initiative enabled a range of extraordinary sanctions, including the prohibition of financial transactions between U.S. citizens and the governments on the list, as well as preventing international financial institutions from extending any credit to these governments. See, “State Sponsors of Terrorism.”

[cix] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2017,” U.S. Department of State, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2017/; “Roll Call Votes,” Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representative, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://clerk.house.gov/Votes?BillNum=H.R479&CongressNum=115&Session=1st.

[cx] U.S. Congress, “H.R.479,” Congressional Bills, 115th Congress, January 12, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-115hr479ih/html/BILLS-115hr479ih.htm.

[cxi] “Remarks by President Trump on His Trip to Asia,” White House Archives, November 15, 2017, accessed date February 12, 2022. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-trip-asia/.

[cxii] “United Nations General Assembly.”