Efe Tokdemir, Bilkent University

İlker Kalın, Center for Foreign Policy and Peace Reserach (CFPPR)

Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, University of Maryland

Deniz Aksoy, Washington University in Saint Louis

David B. Carter, Washington University in Saint Louis

Cyanne E. Loyle, Pennsylvania State University and Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

Seden Akcinaroglu, Binghamton University

Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, University of Essex and Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

Abstract

In this forum article, we examine the state of the field of Peace and Conflict Studies in providing a platform to incorporate local knowledge to generate global insights. Many scholars in peace and conflict studies have traditionally relied on cross-national empirical analyses to investigate conflict dynamics, which can present opportunities for increased level of collaboration, methodological advancement, and interdisciplinary works. Whereas Western-oriented institutions and approaches serve as the locomotive of the production in the field, the vast majority of their data locates in non-Western contexts with diverse cultural, political, social, linguistic, and economic settings. Hence, the overarching theme of this forum emphasizes the benefits of an empirically-driven, methodologically rigorous research agenda that strongly incorporates local knowledge. We offer a platform to discuss the limits and prospects of Global North- South cooperation, the challenges of gathering dependable data, and the ways to overcome these issues while maintaining academic integrity and deepening our understanding of conflict dynamics. We believe that sustained investment in collaborative partnerships and capacity-building initiatives will be critical for unlocking the full potential of local expertise and insights in advancing knowledge-production and fostering peace and stability in conflict-affected areas.

Introduction

Efe Tokdemir, Bilkent University

Ilker Kalin, CFPPR

The discipline of International Relations (IR) has long been criticized for its West-centric orientation, marked by a lack of diversity and a tendency to prioritize research and theoretical perspectives originating in the Global North.[i] This inherent bias is problematic due to the disconnect between the subjects under investigation and the scholars studying them. Often, research on world politics is conducted by scholars geographically distant from the regions they examine.[ii] This does not only limit the quality of the research, but also neglects the nuanced perspectives, experiences, and agency of those closely connected to the issues being analyzed.[iii]

In this forum, we propose that Peace and Conflict Studies presents an ideal platform to explore these dynamics and serves as a channel through which local knowledge can inform global insights. While scholars in peace and conflict studies have traditionally relied on cross-national empirical analyses to investigate conflict dynamics, there is an increasing recognition of the need to incorporate local knowledge for a more nuanced understanding.[iv] Generalizable theories are valuable in identifying global patterns and key variables driving conflicts, but they often fall short in explaining specific cases or sub-national conflict dynamics. In fact, such theories may oversimplify the complex realities on the ground. Without a thorough understanding of the local contexts in which conflicts unfold, it is nearly impossible to grasp the complicated dynamics involving various local actors, let alone propose viable resolutions.[v]

As Cyanne E. Loyle and Seden Akcinaroglu highlight later in this forum, much of the major research and publications in conflict studies focus on the Global South, albeit with disproportionate attention to certain countries. Most of this research, however, is conducted in the Global North, with only a small percentage involving collaboration with scholars from the Global South. This forum, therefore, calls for the inclusion of local knowledge and reliable data through improved Global North-South cooperation.[vi][vii] We believe that prevalent questions in the field, such as the causes and consequences of conflicts and potential conflict resolution mechanisms, demand a nuanced understanding of local actors and contexts. Scholars need to engage with local power dynamics, gender relations, culture, history, and civil society to provide deeper insights.

Here, Tokdemir and Kalin argue that achieving a truly Global IR can be also advanced - or at least initiated - through the further development of mid-range theories in Peace and Conflict Studies. With the evolving nature of conflicts shifting heavily from interstate to intrastate dynamics in the last decades,[viii] these conflicts are increasingly detached from traditional Western frameworks predominantly occurring in non-Global North contexts. To effectively understand the root causes of such conflicts and propose sustainable resolution mechanisms, the discipline must cultivate a deeper examination and appreciation for local experience, insights and observations that emerges organically within these communities.[ix]

Central to this endeavor is establishing genuine collaboration between scholars from the Global North and South. We acknowledge, however, that there are significant challenges to achieving this cooperation, including language barriers, limited resources, restricted access to context, and a lack of well-established network institutions. Despite these obstacles, there are promising models and initiatives that demonstrate what is possible when scholars engage in meaningful partnerships. Indeed, this very forum is the product of online workshops among scholars, some of whom have never met in person. Another notable example is the online writing sessions organized by Hintz,[x] which was initiated following the 2023 earthquake in Turkey and Syria, inviting scholars from the affected regions to join weekly.

The overarching theme of this forum emphasizes the benefits of an empirically-driven, methodologically rigorous research agenda that incorporates local knowledge. Through this forum, we aim to provide a platform for scholars who recognize existing imbalances and problems and want to make a positive impact on the direction of the field via incorporating local knowledge and enhancing collaboration opportunities. To this end, we discuss the barriers to effective Global North-South cooperation, the challenges of gathering reliable data, and the ways to overcome these issues while maintaining academic integrity and deepening our understanding of conflicts. Incorporating local knowledge into conflict research enhances the accuracy, relevance, and sustainability of conflict resolution strategies. Looking ahead, sustained investment in collaborative partnerships and capacity-building initiatives will be critical for unlocking the full potential of local knowledge in fostering peace and stability in conflict-affected areas. Additionally, these collaborative efforts could enhance reflexivity in research, leading to more robust outcomes while reinforcing the epistemological and ethical foundations of the discipline.[xi] In these aspects, authors of this forum critically engage with the discipline while also offering a self-reflective critique of their own positions within it. We hope that our call for the academic community to engage more deeply with these issues resonates and inspires action.

In this forum article, the following key questions will guide our discussions: How has conflict research evolved in terms of empirical data collection and methodologies? How has the digital age and the advent of big data transformed the study of conflict? What are the opportunities and limitations of these new data sources? How can local knowledge contribute to more contextually relevant and sustainable conflict resolution strategies? What challenges arise in incorporating local perspectives, and how can these be addressed? How can scholars maintain academic rigor while integrating indigenous perspectives and fostering cross-cultural understanding? What successful models of North-South collaboration exist in conflict studies, and how can they be expanded? Lastly, what emerging trends and methodologies will shape the future of conflict research, and how might they influence our understanding of conflicts?

Kathleen G. Cunningham’s essay traces the evolution of conflict research, examining key developments in methodologies, data usage, and types of conflict. Cunningham advocates for greater cooperation with local partners, noting the growing recognition that large-scale analyses benefit from the inclusion of local perspectives.

David B. Carter and Deniz Aksoy follow with a discussion on the challenges of accessing local knowledge and data. Their essay explores the tension between theoretical frameworks and local realities, advocating for collaboration between scholars, practitioners, and local stakeholders. They emphasize the need for interdisciplinary scholarship, methodological diversity, and the importance of balancing academic rigor with local insights.

Seden Akcinaroglu and Cyanne E. Loyle continue this discussion by presenting models of North-South cooperation, supported by recent data. They highlight the growing trend toward collaboration, while stressing that more needs to be done. By fostering partnerships with local expertise, expanding institutional networks, and promoting regional centers, the field can overcome existing challenges and improve the quality and impact of micro-level conflict research.

Finally, Kristian S. Gleditsch offers a forward-looking perspective, examining emerging trends and factors likely to shape the future of conflict research. While acknowledging the uncertainty of precise predictions, Gleditsch suggests that the participation of scholars from the Global South, the growth of data availability, the development of new methods, and changes in how research is disseminated will all play a pivotal role in shaping the future of the field.

In conclusion, this forum underscores the importance of scholarly cooperation and the inclusion of local knowledge in conflict research. Through collaboration, we can advance the field, making it more inclusive, relevant, and capable of contributing to a more peaceful and secure world. As discussed later in this forum, an ideal approach would involve collaborative models where researchers work together on shared research questions, and engage in data collection, theory building, and the co-authorship of publications. However, realizing this vision requires overcoming persistent structural barriers, such as limited methodological pluralism, differing research priorities, and the diverse career incentives that shape academic trajectories across regions. Addressing these issues might necessitate a reimagining of the norms governing academic publishing, with greater emphasis on supporting methodologically diverse work, providing language assistance, and ensuring open-access dissemination.

We believe that this call for enhanced Global North-South cooperation is timely, given the increased flexibility and connectivity offered by the digital age. The proliferation of online platforms and social media now enables scholars to connect with potential collaborators from around the world more easily than ever. In the post-COVID-19 era, virtual webinars and meetings have become a common feature of academic life, democratizing access to knowledge for individuals who might not otherwise have had the means to participate.

We also recognize advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and large language models are transforming social science research, making data collection and analysis more efficient and less costly. This digital revolution offers a unique opportunity to integrate local scholars and experts into research processes, ultimately enriching the field of Peace and Conflict Studies with more nuanced, context-sensitive insights. In so doing, collaborative efforts that prioritize the inclusion of local perspectives will not only elevate the quality of research but also promote a more just and equitable approach to knowledge production. By bridging the gap between the Global North and South, we can better address the complexities of contemporary conflicts and contribute to building a global field of peace and conflict studies that reflects diverse experiences and scholarly voices from around the world.

Evolution of Conflict Research: Empirical Data and Methodologies

Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, University of Maryland

Conflict research has evolved significantly over the decades, driven by advances in data availability, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks. In this essay, I explore the trajectory of this field, highlighting key developments in the study of different types of conflict, data sources utilized, and suggesting a way forward through cooperation with local partners.

The study of conflict has historically been categorized into various types, each demanding distinct analytical approach. Initially, the focus was on interstate wars, such as the conflicts between Ukraine and Russia, which spurred inquiries into the triggers and dynamics of such large-scale confrontations.[xii] Over time, this evolved into quantitative studies that sought to identify patterns and predictors of conflict onset.

Concurrently, civil wars and inter-group violence within states garnered attention, revealing complexities in conflict dynamics often overlooked in interstate analyses.[xiii] Comparative politics contributed significantly here, offering insights into intercommunal tensions and the empirical study of violence, including one-sided violence in which civilian populations are targeted by state and non-state actors alike.[xiv]

Terrorism emerged as a specialized area within conflict studies, with a particular emphasis on tactics like suicide attacks.[xv] This subfield underscores the specificity of violent tactics and their implications for broader conflict dynamics. Moreover, recent scholarship has emphasized the integration of violence with non-violent tactics employed by actors, revealing nuanced strategies in conflict settings.[xvi]

1.1. Shifting units of analysis

The evolution of conflict research also saw shifts in the unit of analysis, moving beyond traditional state-centric approaches. Early studies focused on international systems theories, examining systemic conditions conducive to conflict. This evolved into monadic and dyadic analyses, which explored the predispositions of individual states and pairs of states towards conflict, respectively.[xvii] The democratic peace literature, for instance, epitomizes this shift towards understanding patterns in interstate relations.

With the rise of civil war studies, there was a recognition of the interdependence between states and the strategic environments that influence conflict dynamics.[xviii] This led to a broader exploration of regional dynamics and contagion effects across borders. Subsequently, there was a disaggregation of analysis levels, incorporating triadic approaches that included foreign states and international organizations influencing conflict dynamics.[xix]

Further disaggregation occurred with the advent of events data and geocoded analyses. Events data, such as those from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) and Social Conflict Analysis Data (SCAD) projects, provided fine-grained insights into specific conflict incidents, offering a more detailed understanding of conflict dynamics compared to traditional dyadic studies. Geocoded data enhanced this by mapping conflict events spatially, elucidating geographical patterns and their impact on conflict trajectories.[xx]

1.2. Diverse outcomes studied in intrastate conflict

Quantitative studies of conflict have traditionally focused on several key outcomes: onset, duration, termination, and recurrence. These outcomes reflect varying dimensions of conflict dynamics, from understanding when and how conflicts start to predicting their future occurrences. Onset studies initially centered on identifying conditions predisposing countries to civil war, later expanding to include the identification of potential conflict disputes.[xxi] Termination studies have explored diverse outcomes, such as victory, negotiated settlement, or gradual cessation of hostilities, highlighting the multifaceted nature of conflict resolution.[xxii]

Intensity, often measured by the number of battle deaths, remains a critical metric in conflict research, though debates persist regarding its interpretation in light of healthcare disparities and changing perceptions of violence over time.[xxiii] Recurrence studies, meanwhile, delve into the factors influencing the re-emergence of conflicts post-ceasefire, highlighting ongoing challenges in achieving sustainable peace.[xxiv]

1.3. Methodological approaches

Methodologically, conflict research has embraced diverse approaches to data analysis. Early quantitative studies heavily relied on regression analysis and time-series cross-sectional data to identify patterns in conflict dynamics.[xxv] Duration analysis has been crucial in understanding how conflicts evolve over time, offering insights into their temporal dimensions.[xxvi]

Network analysis has gained prominence for its ability to capture complex relationships between actors in conflict systems, uncovering patterns of interaction and influence.[xxvii] Survey experiments have complemented observational data by providing insights into individual decision-making and behavior in conflict settings, validating theoretical assumptions with experimental evidence.[xxviii]

Emerging approaches, such as those rooted in machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI), represent a paradigm shift towards inductive analysis in conflict research. These methods leverage large datasets to uncover patterns and predict outcomes, offering new avenues for understanding complex conflict dynamics beyond traditional hypothesis-driven approaches.

The field of conflict research has been significantly transformed by advancements in data acquisition and analysis methodologies. This section explores the evolution of data sources utilized in conflict studies, ranging from traditional news archives to contemporary social media and crowdsource platforms.

2.1. Traditional news sources

Historically, researchers have heavily relied on publicly available news sources for gathering data on conflict dynamics. Platforms like Factiva and Nexis Uni have served as repositories of aggregated news articles, providing insights into events, actors, and sentiments related to conflicts globally. These sources are particularly valuable for capturing mainstream media narratives and public discourse surrounding conflicts.

However, the use of traditional news sources comes with inherent challenges and biases. News coverage tends to prioritize certain events and perspectives over others, influenced by factors such as media attention and editorial decisions. Thus, while valuable, data sourced from news archives may not always present a comprehensive or unbiased view of conflict dynamics, necessitating careful interpretation and validation.

2.2. Social Media Data

In recent years, the proliferation of social media platforms has opened new avenues for studying conflicts. Platforms like Twitter have been leveraged for sentiment analysis, providing real-time insights into public attitudes and reactions towards conflict events and actors. Researchers analyze user-generated content to gauge public opinion, track the spread of information, and identify emerging trends.[xxix]

Despite its potential, social media data poses significant challenges. Access to comprehensive datasets is often gated, requiring specialized tools and permissions for effective analysis. Moreover, the authenticity and representativeness of social media content remain contentious, as user behavior and content generation can be influenced by algorithms, bots, and varying cultural norms across regions.

2.3. Crowdsource Data

Crowdsource platforms have emerged as another source of real-time data on conflict dynamics. Projects like crowd counting and localized reporting initiatives in conflict zones, such as in Ukraine, provide granular insights into events and trends on the ground.[xxx] These initiatives offer researchers opportunities to access firsthand information and validate broader analyses derived from traditional sources.

However, crowdsource data also comes with unique challenges. Quality control and verification of information are critical issues, as data accuracy and reliability can vary significantly based on contributors’ perspectives and methodologies. Despite these challenges, crowdsource data supplements traditional sources by offering timely and contextually rich information directly from conflict-affected areas.

2.4. Forward thinking: Innovations in data generation

Looking ahead, the future of conflict research is poised to embrace technological advancements and innovative methodologies for data generation and analysis. AI, and resources like ChatGPT present a promising frontier in automating data extraction and analysis from vast document repositories, such as news archives and policy reports. While AI can enhance efficiency in data processing, its integration requires careful calibration and validation against human-coded datasets to ensure accuracy and reliability.[xxxi]

Moreover, addressing inherent biases in data collection remains a critical priority. Researchers are increasingly challenged to confront biases stemming from media coverage preferences, centralized news production, and the diminishing granularity of localized reporting. Innovative modeling techniques and interdisciplinary approaches hold promise in mitigating these challenges while preserving the integrity and richness of data used in conflict studies.

Furthermore, the growing recognition of civilian agency in conflict settings underscores a paradigm shift towards understanding complex interactions between civilians and violent actors. Scholars such as Michael Rubin, Oliver Kaplan, and Cassy Dorff are pioneering efforts to incorporate civilian perspectives into conflict analyses, illuminating their roles in shaping conflict processes and outcomes.[xxxii]

As conflict research continues to evolve, the integration of diverse data sources and methodologies will be crucial in deepening our understanding of conflict dynamics and informing effective policy interventions. Embracing technological innovations and interdisciplinary collaborations promises to enrich the field, offering new insights into the complexities of modern conflicts and their broader societal impacts.

The landscape of conflict research is enriched by established data projects such as the Uppsala Conflict Data Project, Ethnic-Power Relations, ACLED, Correlates of War, and the Polity Data Set. These repositories provide invaluable resources for understanding broad trends and patterns in conflict dynamics globally. However, the evolving nature of scholarly inquiry demands new approaches and data sources that can address nuanced, understudied aspects of conflicts.

While large, institutionally supported data projects offer comprehensive coverage, they may not always align with the specific needs of cutting-edge research questions and theoretical frameworks. Many contemporary studies in conflict research require data that are not readily available in off-the-shelf databases. These include detailed analyses of micro-level dynamics, localized events, or specific temporal and spatial contexts that may be overlooked in broader datasets.

To bridge this gap, there is a growing need to support smaller-scale, data-driven projects that are tailored to address emerging questions in conflict studies. These projects focus on generating new datasets that capture unique dimensions of conflicts, whether it is through intensive fieldwork, targeted surveys, or innovative data collection methods. They contribute by enriching the diversity of available data sources and enabling researchers to explore novel hypotheses and theories.

Encouraging collaboration between researchers, institutions, and funding bodies is essential to nurture these innovative data projects. By fostering partnerships, sharing methodologies, and promoting open data practices, the field can collectively advance towards more comprehensive and nuanced understandings of conflict dynamics.

In contemporary conflict studies, there is a growing recognition among scholars that large-scale analyses often require a nuanced understanding grounded in local contexts. This acknowledgment underscores the importance of complementing extensive data-driven approaches with insights derived from direct engagement and collaboration with local communities.

One critical observation is that many of the assumptions driving large-scale data projects originate from perspectives primarily situated in the Global North or Western contexts. This geographical bias can influence the selection of data points, the framing of research questions, and the interpretation of findings. To mitigate these biases, some researchers have adopted strategies such as conducting focus groups or engaging in dialogue with local stakeholders. These efforts aim not only to validate data collected but also to ensure that the research reflects diverse perspectives and priorities.

Collaboration with local scholars and institutions is increasingly emphasized as essential for producing robust and contextually grounded research. Granting agencies in some contexts now require such partnerships, recognizing the value of integrating local expertise and perspectives into scholarly inquiry. By fostering these collaborations, researchers can enhance the relevance and applicability of their studies, bridging the gap between academic insights and the realities on the ground.

The challenge of linguistic and cultural translation in data collection is also highlighted, particularly concerning the accuracy and nuances lost in translated sources. This issue underscores the necessity for meticulous validation and cross-referencing of information across multiple sources to ensure data integrity and reliability.

Advances in technology, especially virtual platforms like Zoom, have facilitated global collaboration and knowledge exchange among researchers. This technological enhancement enables interdisciplinary teams to spread across different countries to collaborate effectively, leveraging diverse resources and perspectives.

Institutional bodies like the International Studies Association are increasingly prioritizing international collaboration and inclusivity in their strategic planning. However, fostering stronger ties between universities and promoting networks that facilitate professional development and collaboration remain crucial for junior scholars navigating the complexities of global research networks.

The evolution of conflict research has been characterized by a progressive diversification of types studied, shifts in units of analysis, exploration of diverse outcomes, and methodological advancements. These developments not only deepen our understanding of conflict dynamics but also underscore the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary conflict studies, drawing insights from political science, sociology, geography, and beyond.

As conflict research continues to evolve, the integration of diverse data sources and methodologies will be crucial in deepening our understanding of conflict dynamics and informing effective policy interventions. Embracing technological innovations and interdisciplinary collaborations promises to enrich the field, offering new insights into the complexities of modern conflicts and their broader societal impacts.

While existing large-scale data projects remain indispensable in providing foundational insights into global conflict patterns, the future of conflict research lies in supporting and amplifying smaller, innovative data-driven initiatives. These projects not only address current gaps in data availability but also catalyze advancements in theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches. By embracing diversity in data sources and methodologies, the field can better respond to complex challenges and contribute meaningfully to conflict prevention, resolution, and peacebuilding efforts worldwide. To achieve this, the integration of local knowledge and collaborative partnerships holds immense potential. By embracing diverse perspectives and methodologies, researchers can enhance the depth and applicability of their findings, contributing to more comprehensive understandings of conflict dynamics and fostering meaningful impacts in global peace and security studies.

Challenges in Accessing Local Knowledge and Data

David B. Carter & Deniz Aksoy, Washington University in Saint Louis

Among both academics and policymakers, figuring out how to better use local knowledge to develop conflict resolution strategies is a critical area of inquiry. This essay delves into the interplay between general theoretical frameworks and local knowledge, with the aim of enhancing our understanding of how local knowledge can enrich the theory and practice of conflict resolution.

Debates often center around tensions between theory and evidence from cross-national empirical studies and fine-grained details about specific armed conflicts and the localities where they occur. Scholars, particularly in the peace science tradition, have historically relied on cross-national quantitative analyses to analyze conflict dynamics across different contexts.[xxxiii] This approach has yielded valuable insights into the correlates of political violence, civil war, and militarized interstate disputes, offering theoretical frameworks and empirical regularities that provide guidance to both scholars and policy-makers around the world.

However, general conflict theories may sometimes obscure or oversimplify the complex realities on the ground. This limitation can arise because theories necessarily must abstract away from details specific to a particular conflict. The example of Elinor Ostrom’s work on collective action provides a poignant illustration: while the tragedy of the common’s theory posited a universal problem of resource mismanagement, Ostrom’s empirical investigations among indigenous communities in Nepal revealed locally evolved solutions that defied the logic of the canonical theory.[xxxiv] This case underscores the potential for local knowledge to challenge and refine existing theoretical frameworks, thereby offering more contextually relevant insights into conflict dynamics.

The integration of local knowledge into conflict research and conflict resolution practices is important for several reasons. First, local actors, including NGOs, community leaders, and grassroots organizations, possess firsthand insights into the socio-political landscapes within which conflicts unfold. These insights emerge from years of local engagement and experience with local power dynamics, historical grievances, and cultural practices that can shape conflict behaviors and outcomes. By drawing on such knowledge, practitioners and researchers can develop more targeted and effective interventions that resonate with local communities, thereby enhancing the sustainability and legitimacy of conflict resolution efforts.

Moreover, local knowledge fosters a deeper appreciation for local conflict resolution mechanisms that have developed organically within communities. These mechanisms often emphasize reconciliation, consensus-building, and adaptive governance structures that align with local values and norms. Integrating these practices into broader peacebuilding strategies not only enhances their cultural appropriateness but can also better foster community trust and ownership over the process, which can be essential for long-term peace and stability.

Despite its evident benefits, integrating local knowledge into conflict research and conflict resolution frameworks presents several challenges. One significant challenge is the potential for bias introduced by general theoretical perspectives or preconceived notions about conflict dynamics. As noted by Robert Jervis in his pathbreaking work on perception and misperception, researchers may inadvertently prioritize theoretical coherence over empirical ambiguity, thereby overlooking critical insights that deviate from established paradigms.[xxxv] Overcoming this bias requires a conscious effort to engage deeply with local narratives, actively listening to diverse perspectives, and remaining open to revising theoretical frameworks in light of empirical realities.

Furthermore, the process of integrating local knowledge demands a collaborative approach that bridges disciplinary boundaries and fosters partnerships between academic researchers, practitioners, and local stakeholders. Such collaborations not only enhance the credibility and relevance of research outcomes but also contribute to capacity-building initiatives within local communities, empowering them to actively participate in shaping their own peacebuilding processes.

In contemporary conflict resolution scholarship and practice, the role of local knowledge provided by NGOs and local experts is recognized as important to understanding and addressing conflict.[xxxvi]

Local NGOs and experts possess a unique advantage: proximity and direct access to on the ground conflict realities. Unlike more distant observers, they are immersed in the local context, interacting daily with government officials, community leaders, and various stakeholders involved in or affected by conflicts. This close engagement enables them to closely monitor policies and actions taken by conflicting parties. For instance, initiatives such as inter-ethnic collaborative educational environments or vocational training programs are ones that local experts can firsthand observe and evaluate their potential impact on conflict dynamics.

Moreover, local knowledge facilitates rigorous research and evaluation efforts that are crucial for effective conflict resolution. Local experts can initiate and oversee program evaluation projects to assess the effectiveness of government policies or international interventions aimed at conflict prevention and resolution. This capability is exemplified by initiatives like the Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) network, which collaborates with local NGOs globally to evaluate the effectiveness of peacekeeping operations or election observer missions’ impact on election violence. Such collaborations not only leverage local expertise but also integrate it with global academic research, enhancing the robustness and applicability of findings.

The synergy between local knowledge and global research expertise is essential for bridging the gap between theoretical frameworks and empirical realities. While general theories offer broad insights into conflict dynamics, they can overlook nuances specific to local contexts. Local knowledge, on the other hand, provides nuanced understanding grounded in local histories, cultures, and socio-political dynamics. Such understanding is crucial for developing conflict resolution strategies that are culturally sensitive, contextually appropriate, and sustainable over the long term.

Despite its advantages, integrating local knowledge into broader conflict research presents challenges. These include logistical difficulties in data collection, and the need for capacity-building among local stakeholders to ensure their meaningful participation in research and policy-making processes. Overcoming these challenges requires collaborative efforts that prioritize mutual respect, trust-building, and shared learning between local practitioners and global researchers.

In the realm of conflict studies, researchers often encounter significant challenges in accessing and effectively incorporating local knowledge. Below we point out some of these challenges and discuss potential strategies for mitigating them.

2.1. Language barriers

One of the foremost hurdles that researchers face is language proficiency. Understanding local contexts often requires fluency in the native language, which facilitates accessing archival materials, conducting interviews, and engaging with local experts. For example, in Turkey, local knowledge is primarily documented in Turkish, and researchers without proficiency in the language struggle to access local perspectives and insights crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the context. To address this, institutions and researchers need to invest in language training programs or collaborate with bilingual scholars.

2.2. Limited resources and time constraints

Another significant obstacle is the scarcity of resources, both financial and temporal. Research projects that require immersion in local context demand substantial travel funds for transportation, accommodation, and other fieldwork expenses. Moreover, time constraints due to other academic responsibilities such as teaching and administrative duties further restrict researchers’ ability to dedicate extended periods to fieldwork. Addressing these challenges necessitates access to grants specifically tailored for fieldwork in conflict-affected regions, and institutional support that accommodates flexible academic schedules conducive to intensive field research.

2.3. Access restrictions to archives

Government restrictions on accessing sensitive archival materials present another important barrier to obtaining local knowledge, particularly in countries grappling with or emerging from conflict. These governmental restrictions limit researchers’ abilities to explore historical contexts and understand long-term dynamics. Overcoming this challenge requires advocacy for transparent archival policies and collaborative efforts between international researchers and local institutions to navigate bureaucratic hurdles.

2.4. Establishing collaborative networks and partnerships

Effective integration of local knowledge is easier with robust collaborative networks with local NGOs, government agencies, and academic institutions. For researchers outside the local context, building such networks can be difficult. However, international conferences and interdisciplinary projects can serve as crucial platforms for fostering collaborative networks. For example, an interdisciplinary project on Trust and Public Health at Washington University in St. Louis has facilitated connections among scholars in political science, sociology, public health, medicine, and statistics, also leading to connections to scholars in Nigeria that otherwise would not have been made.[xxxvii]

Moving forward, enhancing access to local knowledge requires following more inclusive and collaborative research practices. This entails broadening the scope of research teams to include diverse perspectives and expertise from both global and local scholars. Such collaborative efforts not only enrich data collection and analysis but also ensure that research findings resonate with and address the specific needs of local communities affected by conflict.

In the field of conflict studies, integrating local perspectives while maintaining academic rigor presents a challenge and an opportunity. Here we examine some strategies to strike a balance between incorporating local knowledge and upholding scholarly standards. We emphasize the importance of engaging in interdisciplinary research and employing diverse research methodologies.

Engaging in interdisciplinary research can be one effective strategy to enrich academic research with local knowledge. While political science provides valuable frameworks for understanding conflicts, incorporating insights from disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, psychology, economics, and history enhances contextual understanding. These disciplines often employ qualitative methods that offer detailed insights into local contexts. For instance, anthropological studies, such as Jocelyn Viterna’s work on women’s participation in armed movements in El Salvador, provide in-depth, qualitative analyses that enrich political science research with contextual details and local narratives.[xxxviii]

Embracing diverse methodological approaches beyond disciplinary boundaries is also important. While we have mostly relied on quantitative methods in our research, interaction with qualitative work and scholars can yield new insights for all involved. Qualitative studies offer depth and nuance, while quantitative studies uncover systematic patterns. These two complementary approaches can together generate richer and more comprehensive empirical findings that take local insights seriously while retaining rigor and generalizability.

Accessing local knowledge often entails engaging with literature and sources authored by local experts and scholars. Many important works and critical insights about specific regions or conflicts are published in local languages, highlighting the importance of translation efforts and collaboration with bilingual scholars. By reading local authors and following regional news sources, researchers gain access to local perspectives.

While interdisciplinary and methodologically diverse approaches offer promise, researchers face challenges such as language barriers, limited availability of local literature in international languages, and access to sensitive archival materials. Overcoming these challenges requires institutional support for language training, collaborative partnerships with local institutions, and advocacy for open access to archival resources.

In the digital age, the proliferation of social media and online sources has revolutionized data collection in conflict studies. The advent of Web 2.0 has ushered in unprecedented opportunities for researchers in conflict studies. Social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and others provide vast quantities of real-time data. Researchers can analyze armed actors’ behaviors, government responses, legislative discourse, and public sentiment with unprecedented granularity. This accessibility was inconceivable before the digital era, offering insights into propaganda dissemination, citizen engagement, and societal responses.

Technological advances also enable the automated scraping and coding of data from diverse online sources beyond social media. Official government statements, legislative speeches, and insurgent group websites now serve as valuable repositories of data that can be swiftly converted into analyzable formats. Moreover, the digitization of historical archives, from old civil service exams to ancient maps, expand the temporal scope of research, providing historical context through previously inaccessible digital resources.

However, alongside these opportunities, significant challenges persist. Authenticity remains a primary concern in data sourced from online platforms. The prevalence of bots and anonymous users complicates the distinction between genuine human interactions and automated or manipulated content. Moreover, the digital realm often diverges from real-world behaviors, raising questions about the representativeness and validity of online data in reflecting offline realities.

The sheer volume of data available poses another challenge. Researchers confront the daunting task of sifting through vast datasets to identify relevant information while determining what to discard or prioritize. This process demands robust analytical frameworks to extract meaningful insights amidst the noise of irrelevant or misleading data.

Triangulating data sources can help to mitigate these challenges. Traditional data collection methods, rooted in established research methodologies, offer complementary insights that can help validate findings based on online sources. By triangulating data from both digital and traditional sources, researchers can enhance the robustness and reliability of their findings.

To develop contextually relevant conflict resolution strategies necessitates a balanced integration of general theoretical frameworks with detailed local knowledge. While cross-national research offers valuable insights into global trends and patterns, local knowledge can enrich our understanding by contextualizing these insights within specific conflict settings.

The integration of local knowledge into conflict research helps enhance the accuracy, relevance, and sustainability of conflict resolution strategies. By empowering local NGOs and experts to contribute their insights and observations, we not only enrich academic research but also strengthen the effectiveness of practical efforts to mitigate and resolve conflicts worldwide. Moving forward, continued investment in collaborative partnerships and capacity-building initiatives will be essential for harnessing the full potential of local knowledge in fostering peace and stability in conflict-affected regions.

While accessing and incorporating local knowledge into conflict studies presents some challenges, concerted efforts to address language barriers, resource constraints, data access restrictions, and establishing global research networks can pave the way for more nuanced and impactful research outcomes. By embracing interdisciplinary collaborations and fostering partnerships across geographical and institutional boundaries, researchers can better integrate local knowledge to advance conflict resolution strategies worldwide. Forums like this provide valuable opportunities to exchange insights and build the networks necessary for overcoming challenges to access local knowledge.

Achieving a balance between local knowledge and academic rigor in conflict studies demands a commitment to interdisciplinary scholarship, methodological diversity, and engagement with local sources. Moving forward, forums that promote interdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration, such as international conferences and research networks, play a pivotal role in bridging disciplinary divides and integrating diverse perspectives into conflict studies.

Finally, it is important to note that local knowledge is integral to conflict research that relies on field work in a local context, such as in-person surveys. Connecting with local experts or scholars who work or reside in the local context is essential to the success of research that relies on field work. Collaborating with scholars or NGOs that know the local context and speak the local language will increase the quality and validity of research. For example, local knowledge is indispensable in designing effective experimental treatments in a survey. Moreover, including local scholars as collaborators will not only enhance the quality of research but also contributes to a larger and stronger network of global conflict scholars.

Academic Cooperation Between the Global North and the Global South

Cyanne E. Loyle, Pennsylvania State University and PRIO

Seden Akcinaroglu, Binghamton University

Research engagement between Global North and South partners has evolved to encompass various models of collaboration, each with distinct characteristics and benefits. These models reflect diverse approaches to addressing pertinent research questions within the fields of International Relations (IR) and Conflict Studies. The models also reveal the potential challenges and power differentials of engaging in North-South research partnerships.[xxxix] In this essay, we explore three primary models of research engagement: the contract model, the cooperation model, and the collaboration model. We examine the models’ structures, benefits, and drawbacks through real-world examples, illustrating their applicability to different research contexts. Central to this presentation is the argument that partnerships between North and South scholars produce research which is distinct from that which would be conducted in geographical or epistemological silos. In other words, North-South partnerships have the potential to produce important scholarship and to investigate research questions in ways that would not be achievable with single-country research teams.

The contract model of research partnership is characterized by a transactional relationship where a researcher from the Global North hires a local research firm or think tank in the Global South to collect data or conduct specific research tasks. This model is particularly beneficial when a Global North researcher is unfamiliar with the local context or unable to travel to the research site. An illustrative example would be a project conducted in Nepal by a European academic, where a Nepalese think tank is contracted to perform focus groups following the question protocol supplied by the Global North academic. The European scholar does not travel to Nepal, but rather corresponds with the Nepalese think tank on the research and data requirements. Here the local research firm acts as an intermediary to collect data for the scholar without having much engagement in theory development or data analysis.

This model has several advantages. It enables Global North researchers to access data from locations they cannot personally engage with, expanding the geographical scope of their studies. In this way, areas of the world which may be historically excluded from academic study are included in the evaluation of IR and conflict studies theories.[xl] The contract model leverages the skills and local knowledge of resident research firms, enhancing the quality and relevance of the data collected. The model also provides financial and research resources directly to local research firms rather than concentrating funds in Northern institutions. Additionally, the contract model reduces the need for the Northern researcher’s team to travel, often resulting in lower overall project costs and more efficient and environmentally sustainable data collection.

However, the contract model has its drawbacks. Critics have accused this form of international research partnership as being a form of “brain-drain-without mobility” in which local research capacity to focus on local issues is reduced by international research demands and financial incentives.[xli] South-based contracted researchers lack direct involvement in the data generation process, potentially leading to a disconnect between the theoretical framework and empirical data collected for the research project. The lack of engagement between the two groups of scholars does not facilitate knowledge exchange, producing a missed opportunity for scholarly partnership. Moreover, the model may be less effective for certain types of data generation such as qualitative research, where deep contextual understanding and direct interaction with the subject matter is often a crucial step of the research process.

Through the cooperation model, researchers from different regions engage in joint data collection efforts while maintaining independent research projects or questions. This model fosters complementary research without necessitating uniformity in research objectives. An illustrative example of this model would be a survey partnership between U.S. and Turkish scholars where both parties contributed their own question modules to a national survey in Turkey. The two teams could work together sharing expertise and resources, but ultimately ask different research questions and produce different research outputs. Costs could be shared equally or divided based on some other metric.

The cooperation model allows researchers to pool resources, thereby enabling larger and potentially more extensive research than they could achieve independently by each scholar. In this model, researchers maintain autonomy over their individual research questions and methodologies. Yet, this model encourages conversations and mutual learning with the goal of enhancing the robustness of the research design. In the example above, the Turkish team is able to share local expertise in survey design and Turkish politics which benefits the U.S.-based team. The U.S.-based team is able to provide resources to extend the sample size of the survey. Through the cooperation model it is possible for one team to focus specifically on academic outcomes, such as publications, while another team favors a focus on local policy-relevant questions and outcomes. This model, however, requires careful communication and coordination to ensure that the partnership is mutually beneficial to both parties and that resource allocation is equitable, if not equal. Integrating data collected for different research questions can be methodologically complex and may require sophisticated analytical approaches.

The collaboration model involves researchers working together on the same research questions and objectives, often with complementary goals. This model emphasizes collaborative efforts in research design, data collection, and analysis. An example would be research conducted in Mozambique, where a U.S.-based team and a Mozambican team collaborate to collect research on climate change and conflict. Through a collaboration model, both teams would work together to develop the research questions and design the study to collect relevant information. The teams would then collaborate and co-author on the analysis and publications from the research. In this example the research question and data collection for both teams of scholars are unified in a single project.

Like the cooperation model, the collaboration model enables cost-sharing between research partners, making high-quality research more financially feasible for both North and South scholars. Both teams benefit from each other’s research expertise and local knowledge, enhancing the overall quality and relevance of the research. Furthermore, the model potentially supports capacity building in the Global South, as local researchers may be exposed to new skills and experiences by their international counterparts. Ordóñez-Matamoros et al. find that South-based scholars who co-author with North-based scholars are more likely to publish in high quality venues than South-South collaborations, suggesting payoffs from this form of partnership.[xlii] The collaboration model is the standard of research partnership often advocated by international funding agencies where North-South research engagement is prized for its ability to increase the research capacity of South-based research organizations as well as increase the research engagement of South-based scholars.

Nonetheless, managing a truly collaborative project with unified goals can be challenging and requires effective communication and coordination. As we discuss further below, it may be possible that North and South scholars have different research priorities and career incentives. Unless power hierarchies and resource inequities are explicitly brought to light and dealt with head-on there is always a risk that one team may dominate the research agenda, potentially undermining the collaborative spirit.

In conclusion, the contract, cooperation, and collaboration models each offer unique advantages and face distinct challenges in the context of Global North-South research engagements. While the contract model provides efficiency and access for Global North scholars, the cooperation model fosters independence and resource sharing across partnerships, and the collaboration model emphasizes joint objectives and capacity building truly enhancing research synergies. The choice of model should align with the specific research questions, goals, and contextual factors of the project. Reflecting on these models highlights the importance of adaptive and context-sensitive approaches to international research partnership.

This essay explores the distribution and dynamics of micro-level conflict studies, highlighting the challenges and biases in current research methodologies. Through an analysis of articles from leading journals, we reveal a significant disparity in regional focus and collaboration patterns. The findings underscore the need for more inclusive and localized research practices, particularly in underrepresented conflict zones.

Micro-level conflict studies are essential for understanding the nuances and localized impacts of broader conflicts. However, the accessibility and focus of such studies often reflect significant regional and institutional biases. This essay examines the distribution of micro-level studies published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution and the Journal of Peace Research between 2022 and 2024. By analyzing the geographical focus and collaborative patterns of these studies, we identify key gaps and proposes strategies for fostering more inclusive and effective research collaborations.

The data collection involved a comprehensive review of articles published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution (JCR) and the Journal of Peace Research (JPR) from 2022 to March 2024. The review focused on identifying articles featuring micro-level studies, defined as studies utilizing localized data or surveys. A total of 18 issues from JCR (135 articles) and 12 issues from JPR (100 articles) were examined. The articles were coded based on the presence of micro-level data and the geographical regions studied.

Out of 235 articles reviewed, 89 (approximately 38%) featured micro-level studies. Notably, 73% of these studies focused on regions in the Global South, with significant coverage in specific areas like the UK, Russia, Ukraine, and selected African countries. However, many conflict zones, particularly in the Middle East and Africa, remain underrepresented.

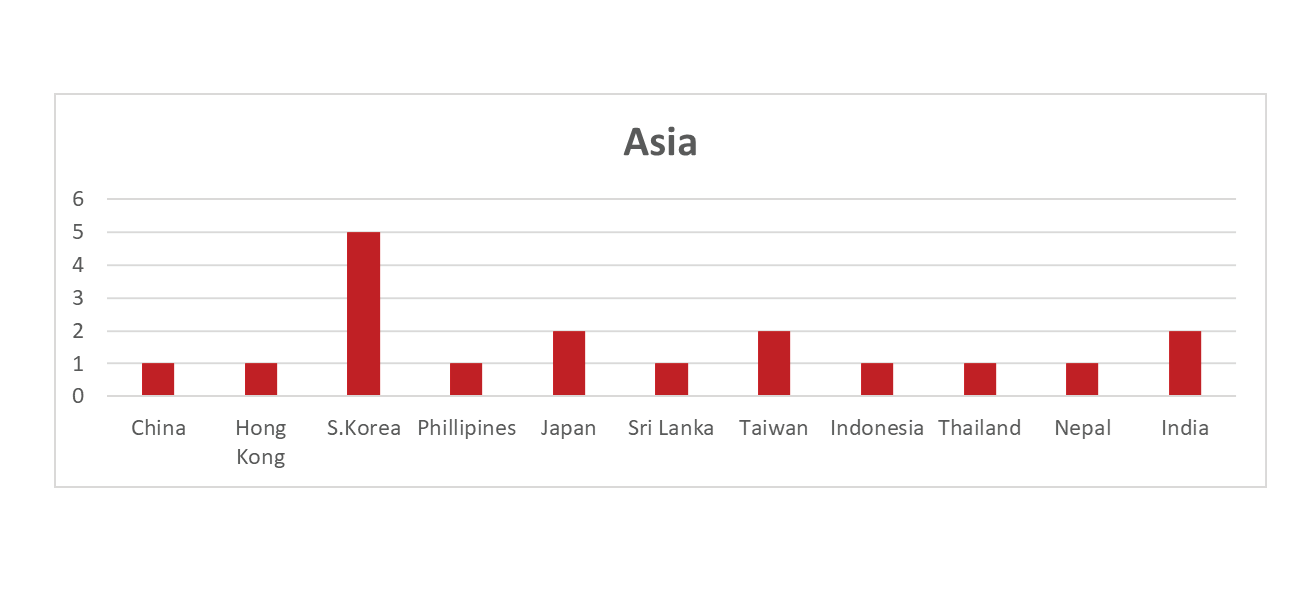

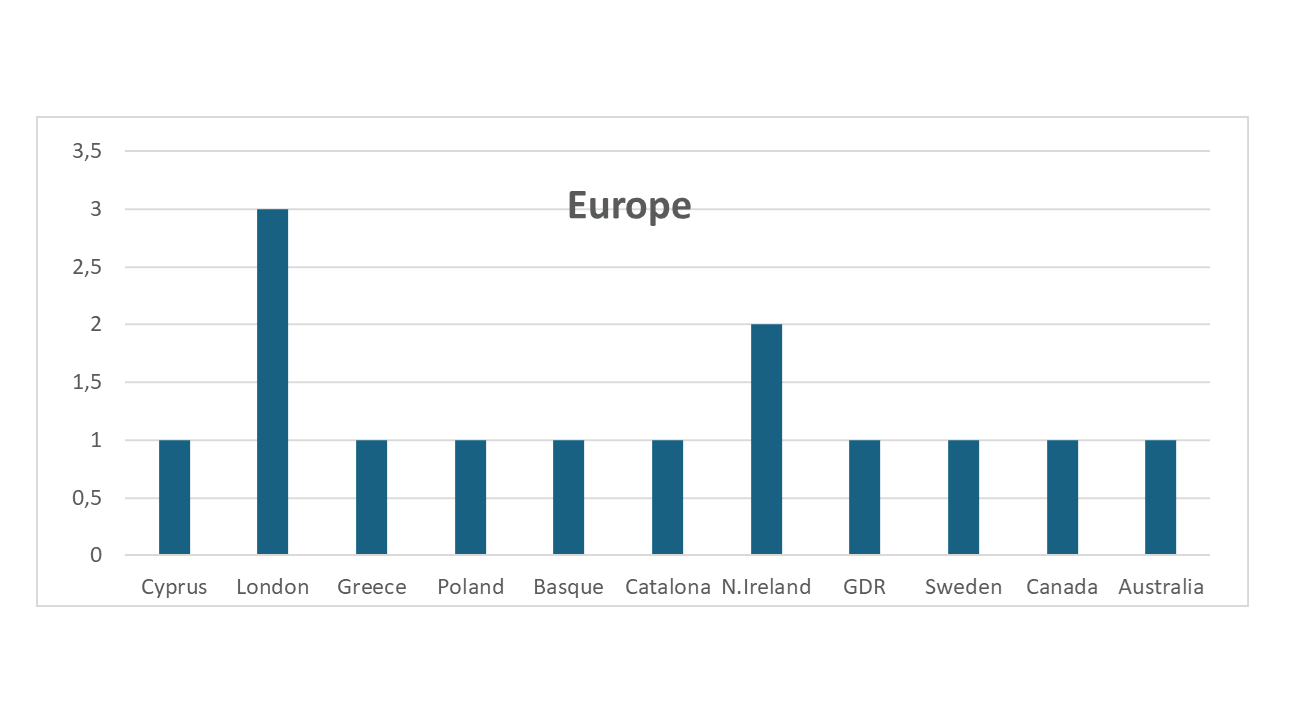

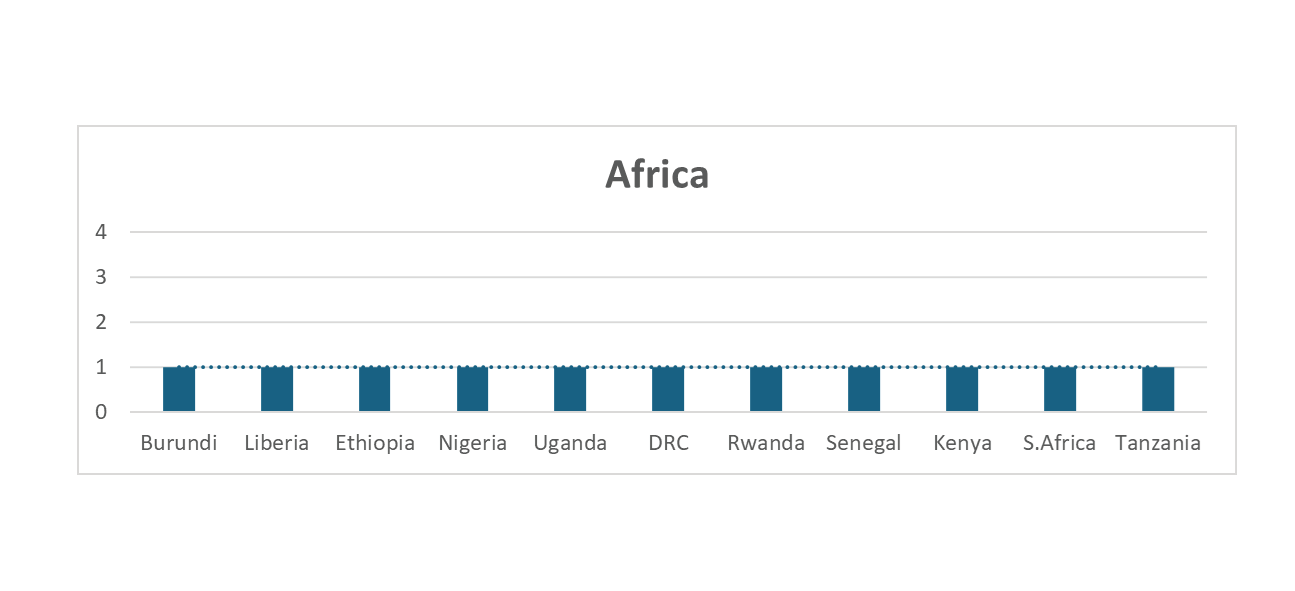

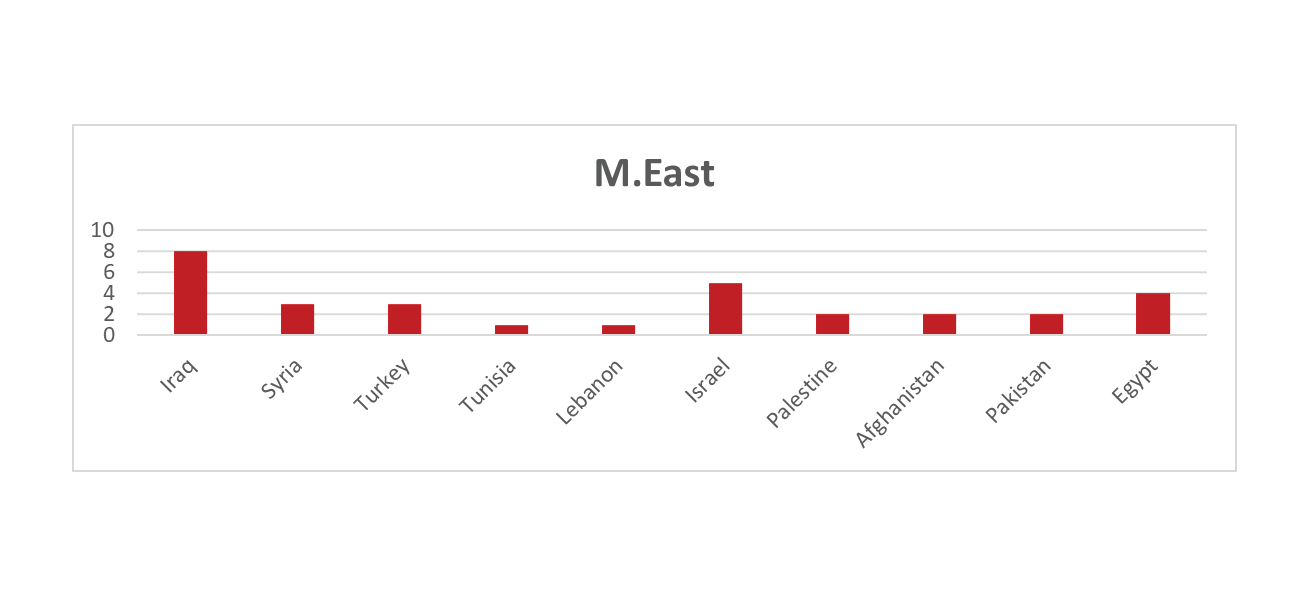

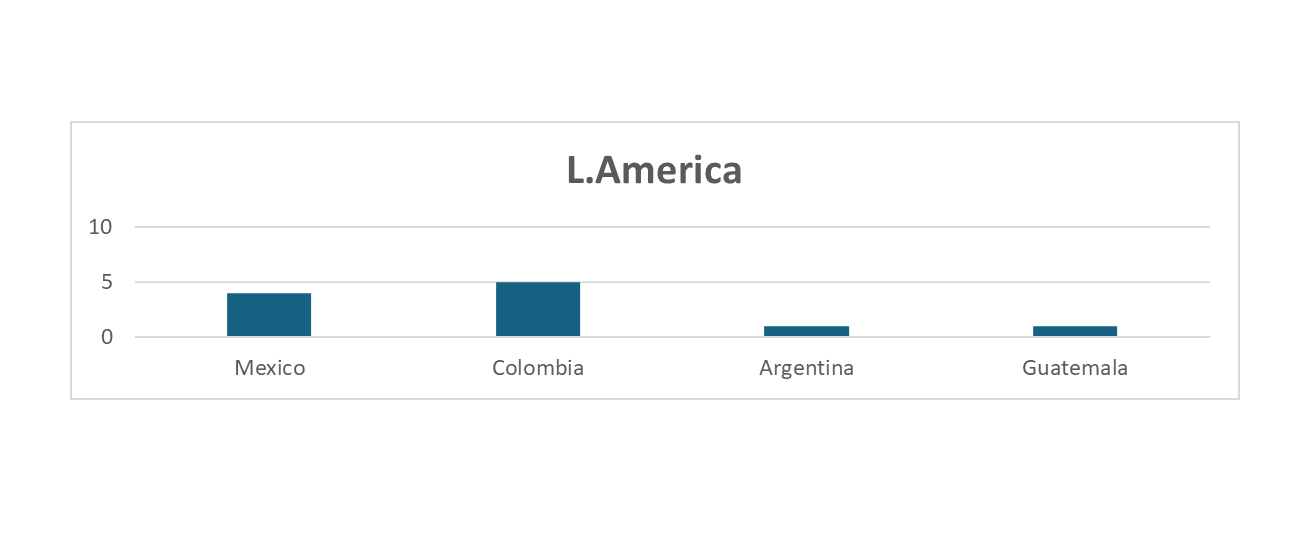

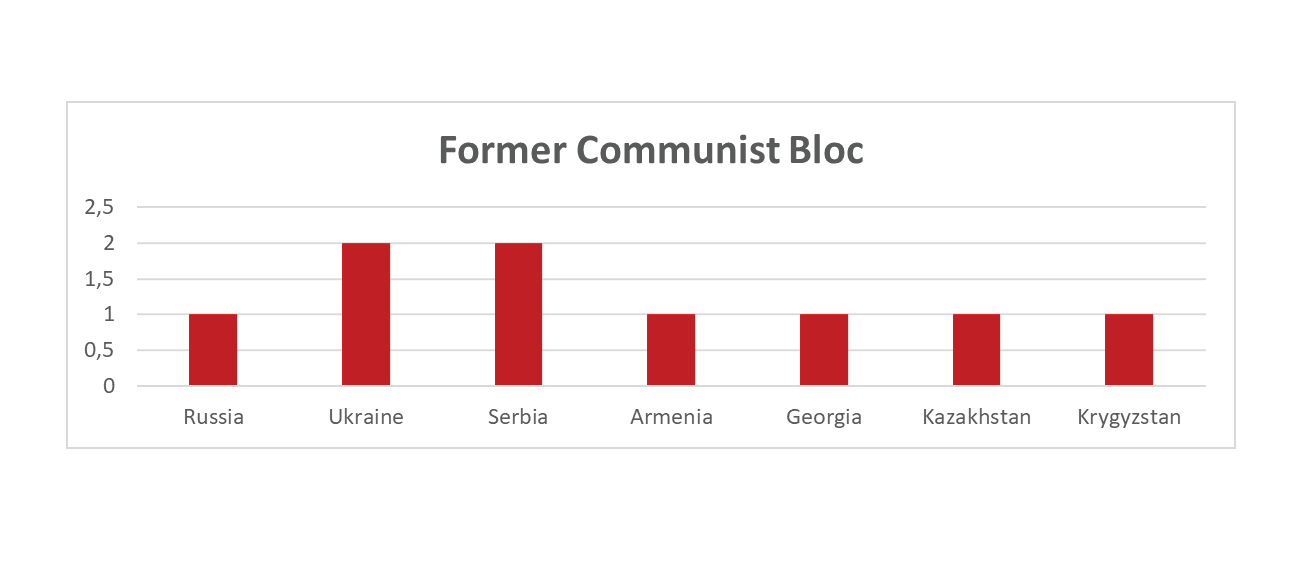

Figure 1: Frequency of Countries Listed in Micro-Level Research According to Regions

The analysis revealed significant regional disparities. The UK and former communist bloc countries like Russia and Ukraine are well-represented, while many African and Middle Eastern conflict zones lack sufficient micro-level research. For instance, only a handful of African countries were covered, with each receiving minimal attention despite being critical conflict zones. Similarly, in the Middle East, studies predominantly focused on Iraq and Israel, leaving other areas under-researched.

We analyzed collaboration patterns among authors, categorizing them into three groups: North-North, North-South, and South-South collaborations. The analysis revealed a significant bias towards North-North collaborations, with 52 out of 89 studies involving partnerships exclusively within the Global North. In comparison, North-South collaborations were present in only 7 studies, while South-South collaborations were rare, occurring in just one instance. This data highlights the limited diversity in collaboration patterns, emphasizing the need for more inclusive and equitable research partnerships across regions.

Table 1: Distribution of Collaboration Patterns Among Authors by Region

| Collaboration Type by Location | Frequency | Percentage |

| Same country (e.g. within the US) North-North Collaboration | 29 | 33% |

| Different country (e.g. US and Norway) North-North Collaboration | 52 | 58% |

| North-South Collaboration | 7 | %8 |

| South- South Collaboration | 1 | %1 |

Interestingly, 18% of the studies had at least one author originally from the country being studied, suggesting an informal North-South collaboration when considering the authors’ nationalities. This highlights the potential for more inclusive research practices through better recognition of authors’ backgrounds and connections.

Several challenges hinder the conduct of micro-level studies in underrepresented regions. Scholars often lack local connections, resources, and access to data, making it easier to rely on large-scale data with limited local context. This results in studies that may not fully capture the causal mechanisms within specific conflict zones. Additionally, reviewers frequently criticize studies for not delving deeply enough into these mechanisms, reflecting the inherent difficulties in conducting thorough localized research without sufficient support.

To address the challenges identified in the current landscape of micro-level conflict studies, several strategic approaches are proposed to foster more inclusive and effective research practices.

One key strategy is the strengthening of North-South collaborations. Encouraging formal and institutionalized networks between institutions in the Global North and South can significantly improve resource sharing and collaborative research efforts. For example, the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership demonstrates the success of such initiatives. This partnership, funded by the National Institutes of Health, has facilitated extensive training, research collaboration, and data collection since 1996, showcasing the potential benefits of well-supported North-South academic cooperation.[xliii]

Another important recommendation is the encouragement of localized expertise.[xliv] Journals and funding bodies should actively reward studies that incorporate local scholars as co-authors. This approach can greatly enhance the contextual sensitivity and depth of micro-level research, ensuring that the studies are more attuned to the specific nuances and dynamics of the regions being examined. By involving scholars who possess intrinsic knowledge and connections within their local contexts, research can achieve a higher level of accuracy and relevance.

Expanding institutional networks is also crucial for fostering more inclusive research environments. Establishing more partnerships between universities and research institutes across different regions can create broader and more diverse academic collaborations. This includes initiatives where Northern universities establish branches in Southern regions and vice versa. Such cross-regional partnerships can help bridge gaps in knowledge and resource availability, enabling more comprehensive and localized conflict studies.

Furthermore, promoting regional institutes and centers that specialize in conflict studies can provide better support and networks for scholars conducting micro-level research. Strengthening these regional institutions can enhance their capacity to serve as hubs for localized expertise and research activities. By bolstering the infrastructure and resources available at these centers, scholars can be better equipped to conduct in-depth and contextually rich studies that address the unique challenges and dynamics of conflict zones.

In summary, by enhancing North-South collaborations, encouraging the inclusion of local expertise, expanding institutional networks, and promoting regional institutes and centers, the academic community can overcome existing challenges and significantly improve the quality and impact of micro-level conflict research.

The divide between the Global North and South in International Relations and Conflict Studies is a multifaceted issue that extends beyond geography to encompass methodological and epistemological differences. The divide captures disparities in the venue of publications, the quantity of published scholarship, as well as the cases and topics selected for study. This divergence reflects deeper philosophical orientations within the academic community, influencing the types of research questions posed and the methodologies employed. This microcosm of the broader North-South academic schism underscores the importance of methodological pluralism and collaborative research for increasing the incorporation of Global South scholars into Conflict Studies.

Recent discussions around decolonizing International Relations (IR) theory have highlighted the inherent bias in much of the early work on state formation, international conflict, and civil wars.[xlv]Many IR theories emerged from analyses of specific European cases which may not be universally applicable.[xlvi] Central to solutions to theory decolonization is the inclusion of Global South scholars in the production of new knowledge and published research. The Global South cannot be part of these conversations unless South-based scholars are actively included. The exclusion of Global South scholarship is the result of several contemporaneous limitations.

Historically, Conflict Studies research was starkly divided into two camps: one favoring quantitative methods and the other adhering to qualitative approaches. Over time, the dominance of quantitative methodology in the subfield became evident, mirroring a broader trend in Northern academic discourse. This shift highlights a key aspect of the North-South divide: the predominance of certain methodologies that shape research questions and outcomes. Northern scholars often prioritize quantitative methods, whereas Southern scholars may emphasize qualitative insights and case-specific implications.

The issue extends beyond the mere existence of separate scholarly journals or research agendas. It involves a lack of mutual understanding and the tendency to view research through isolated lenses. The key to bridging this divide lies in fostering collaborations where Northern and Southern scholars work together on shared projects across different methodological traditions and with potentially different research aims. Such partnerships would facilitate a deeper understanding of diverse perspectives, methodologies, and contextual realities. The ideal academic environment integrates both Northern and Southern perspectives, leading to a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of conflict.

A lack of methodological pluralization has led to gatekeeping. It is not that methods from the Global South are unsophisticated, but journals may be reluctant to publish or engage with them. Northern academic journals interested in broadening their engagement with the Global South should be committed to publishing methodologically pluralistic work, perhaps investing significant energy into translating and editing submissions to ensure language barriers do not hinder publication. This focus on valuing ideas first and addressing methodological or presentation issues second gives scholars the benefit of the doubt.

Another critical aspect of this collaborative approach is the emphasis on meaningful policy implications from academic findings. Northern academics often emphasize the scholarly contributions of their research without ensuring a practical application. In contrast, scholars from the Global South, specifically those living in conflict-affected regions, may be deeply invested in the real-world impact of their research.[xlvii] Collaborative projects can bridge this gap, combining rigorous analytical methods with a commitment to actionable outcomes.

To foster a more robust learning environment, scholars from the Global North and South may engage in sustained, meaningful collaborations. These joint efforts foster mutual understanding, enrich methodological approaches, and enhance the relevance and impact of conflict studies. Such interdisciplinary and interregional partnerships are essential for addressing complex global challenges and advancing diversity within the field of conflict research. The transformation from isolation to integration will not only bridge the North-South divide but also lead to a more dynamic and effective academic community.

However, a more pessimistic aspect to consider is the divergence in goals between Northern and Southern scholars. A key assumption of our recommendations is that Global South scholars are seeking greater exposure in global academic conversations. Many scholars from the Global South may be more focused on achieving policy changes within their own countries or addressing conflict dynamics than publishing their work in international academic venues. Scholars may prioritize publishing op-eds in national newspapers, for example, or writing policy briefs for local ministries over engaging in a broader research dialogue. The divergence of incentives is further heightened by the length of time it takes to have articles reviewed and published, along with challenges of journal paywalls and limited Open Access research.

Recognizing and accommodating these diverse objectives is crucial for successful and meaningful collaboration. Scholars from the Global North and South must acknowledge and respect each other’s goals and work towards integrating their perspectives in order to broaden the theoretical and methodological diversity of Conflict Studies. This integrated approach will not only bridge the methodological and epistemological divides but also lead to research that is both rigorous and relevant, ultimately benefiting the academic community and the broader global society.

In conclusion, fostering North-South collaborations is not merely an academic exercise but a necessary step towards a more comprehensive and impactful approach to Conflict Studies. By working together, scholars can transcend methodological and epistemological divides. This integrated perspective will lead to better-informed policies and more effective conflict resolution strategies, benefiting both the academic community and the broader global society.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Conflict Studies

Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, University of Essex and PRIO

Attempts to consider the future of a research area or discipline inevitably encourage both prediction about what future scientific research may look like given the past and present as well as reflection on the factors that may influence the specific nature of future scholarship. In attempting to provide a possible answer to the future of conflict studies and what might lie ahead I consider three different approaches to forecasting and prediction as well as key factors driving demand for the supply of research. The first perspectives help to imagine how observers can best anticipate likely trends and future scholarship. The last helps us capture how science is a participatory activity in which research ultimately depends on what scientists decide, which in turn will be shaped by their incentives and the resources they have access to. Individual researchers are part of a larger discipline, and increasing globalization and collaboration will figure prominently in my discussion.

A well-known saying is that prediction is very difficult, especially when it is about the future.[xlviii] Often the best way to forecast is to look at past data, seek plausible patterns, and then extrapolate trends into the future. For example, if international collaboration has become more common and has specific consequences, then perhaps we can project more of this in the future. Trend extrapolation is often a useful approach, but not infallible. Financial statements usually come with the standard disclaimer that past behavior is not a guarantee to future results for a good reason. Taleb argues more strongly that what we can predict often is inversely related to its importance. In his view, we tend to be better at predicting white swans, i.e., things that we can observe, enumerate, and forecast using deterministic methods with less uncertainty, but the key things that matter are often black swans, i.e., rare events that may not have been observed in the past and follow probability distributions that make them inherently hard to forecast.[xlix]

A second perspective on forecasting does not question our limited ability to predict but focuses instead on the value of devising explicit models and alternative scenarios. Hughes, when developing the International Futures (IFS) model to simulate global trends, nicely stated how “we cannot know the future, but we must act as if we did.”[l] Structured scenario-based forecasts about possible future outcomes and what could make them more likely are more helpful than efforts to come up with single predictions or “most-likely forecasts,” and explicit models allow us to consider alternatives given different inputs or potential events. Scenario-based forecasts using IFS have been devised for a range of conflict, governance, and development outcomes,[li] and figure prominently in work on issues such as climate change and its potential implications.

A third approach acknowledges fundamental constraints on predictive ability but tries to consider if particular methods or approaches can work relatively better. Tetlock’s seminal studies on predicting political events, where experts were asked to rate the likelihood of different outcomes and then were evaluated against the observed record, clearly suggested excessive confidence in the ability of experts to forecast, and showed that expert predictions are often imprecise or underperformed simple statistical algorithms when verifiable.[lii] But rather than dismiss prediction or just conclude that “political scientists are lousy forecasters,”[liii] Tetlock sets out a useful agenda to examine how one might predict better.[liv] This shows how forecasting can be improved by breaking problems into parts, reasoning separately about components, devising explicit probabilities from existing knowledge, and using Bayesian reasoning to derive and update predictions.

Future conflict studies will obviously be influenced by the conflict landscape itself, since the specific events that occur inevitably call for explanations, and trends often reorient scholarly attention. Notable examples are the growing interest in civil war after the end of the Cold War or terrorism after the 9/11 attacks, and it may be difficult to sustain research on peacekeeping if the United Nations cannot authorize new missions with greater divergence among the permanent five members of the Security Council. Forecasting the conflict landscape is a very broad topic that cannot be adequately covered here, but I want to make three general observations. First, simply extrapolating conflict trends from observed data is often problematic. If severe conflict is a rare event and follows extreme value distributions, then we would need extremely long time series to conclude that the risk of a large war has materially changed even if we have not seen one since the end of World War II.[lv] We may have more confidence in less rare events or other trends that we expect to affect conflict, but in general we need to think of the observed data as a “sample” and compare this to explicit models with random variability.[lvi] Second, although prediction remains difficult, there clearly has been substantial progress in conflict prediction, with more consistent evaluations and comparison, more scenario-based approaches, and greater awareness of what works better and why.[lvii] Third, research itself can influence the future; we see growing interest in how anticipation could influence conflict onset and conflict management efforts, and existing research suggests that early UN action or attention could make violence less likely.[lviii]

On the supply side of conflict studies, I would like to highlight four key and possibly related factors. First, we see clear and important changes in the community of conflict scholars. There is increasing participation from researchers outside the traditional “West” or “Global North,” backed up by data on publications, manuscript submissions, and membership in professional associations such as the International Studies Association, where an increasing share of the organization is now based outside North America—where the organization first emerged and traditionally has been most active.[lix] More diverse participation also goes together – at least potentially - with increasing attention to other areas or topics.[lx] Research is increasingly collaborative and more global, and there are growing examples of cross-country collaborations in published research across World Bank income brackets.[lxi] Greater participation is facilitated by lower barriers to entry into research. The costs of resources such as computing have declined dramatically, much more material is available electronically beyond traditional restricted library access, and relevant data for research are increasingly open. Moreover, internet access can provide scholars opportunities for training and participating in activities anywhere in the world. National origin alone is not a strong or reliable predictor of research content, but a more global discipline can at least in principle provide more manpower and prospects for progress and a potentially more diverse and inclusive research agenda.

Beyond the changes in researchers, a second dynamic supply factor is the growth in the availability of data. New data often drives progress in conflict research.[lxii] Of course, new data must be based on some prior theory or at least implicit assumptions, but new data often allow for interrogating theories better and to further develop theories in better recognition of limitations. A path analysis for conflict research based on citations by Van Holt et al. reveals that key nodes often are presentations of influential data sources.[lxiii] The growth in data in conflict research is likely closely related to the globalization of the discipline. Scholars with detailed knowledge of specific areas and countries can help provide access to new sources, material, and data in ways that can have a transformative impact on conflict studies. Individuals in countries with experience of conflict are increasingly active as researchers in their own right and not just human subjects in studies conducted by others. More specialized data sources and country-specific focuses may induce more divergence in research and less basis for direct comparisons and generalization. True, there are potential challenges from greater fragmentation, however approaches such as meta-analysis can allow us to try to evaluate heterogeneity and better integrate evidence from a wide range of studies.