Akın Ünver

Kadir Has University

Combining discourse analysis with quantitative methods, this article compares how the legislatures of Turkey, the US, and the EU discursively constructed Turkey’s Kurdish question. An examination of the legislative-political discourse through 1990 to 1999 suggests that a country suffering from a domestic secessionist conflict perceives and verbalizes the problem differently than outside observers and external stakeholders do. Host countries of conflicts perceive their problems through a more security-oriented lens, and those who observe these conflicts at a distance focus more on the humanitarian aspects. As regards Turkey, this study tests politicians’ perceptions of conflicts and the influence of these perceptions on their pre-existing political agendas for the Kurdish question, and offers a new model for studying political discourse on intra-state conflicts. The article suggests that a political agenda emerges as the prevalent dynamic in conservative politicians’ approaches to the Kurdish question, whereas ideology plays a greater role for liberal/pro-emancipation politicians. Data shows that politically conservative politicians have greater variance in their definitions, based on material factors such as financial, electoral, or alliance-building constraints, whereas liberal and/or left-wing politicians choose ideologically confined discursive frameworks such as human rights and democracy.

1.Introduction

In the ongoing debate on linguistic methodology, the dominant position argues that discourse analysis is a strictly qualitative “methodological meta-other” of quantitative methods such as statistics,[1]Mats Alvesson and Dan Karreman, “Varieties of Discourse: On the Study of Organizations through Discourse Analysis,” Human Relations 53, no. 9 (2000): 1125-49, doi:10.1177/0018726700539002; Linda J. Graham, “Discourse Analysis and the Critical Use of Foucault,” (paper presented in The Australian Association of Research in Education Annual Conference, Parramatta, Sydney, November 27- December 1, 2005), http://eprints.qut.edu.au/2689/; Gale Miller and Robert Dingwall, Context and Method in Qualitative Research (London: SAGE, 1997). while the opposing position maintains that statistical analysis and its quantitative results can be used as an alternative to mainstream discourse analysis.[2]Gerardo L. Munck and Jay Verkuilen, “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy Evaluating Alternative Indices,” Comparative Political Studies 35, no. 1 (2002): 5-34, doi:10.1177/001041400203500101; Dean Henry, “The Numeration of Events: Studying Political Protest in India,” in Interpretation and Method: Empirical Research Methods and the Interpretive Turn, ed. Dvora Yanow and Peregrine Schwartz-Shea (London: Sharpe, 2006), 187-202; Pamela Paxton, Melanie M. Hughes, and Jennifer L. Green, “The International Women’s Movement and Women’s Political Representation, 1893-2003,” American Sociological Review 71, no.6 (2006): 898-920, doi:10.1177/000312240607100602; Steve Shellman and Sean O'Brien, "An Empirical Assessment of the Role of Emotions and Behavior in Conflict Using Automatically Generated Data," All Azimuth 2, no. 2 (2013): 31-46. Attempts at combining these approaches[3]Paul Baker et al., “A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press,” Discourse & Society 19, no. 3 (2008): 273-306, doi:10.1177/0957926508088962; Theo Van Leeuwen, Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Teun A. Van Dijk, “Ideology and Discourse Analysis,” Journal of Political Ideologies 11, no.

2 (2006): 115-40, doi:10.1080/13569310600687908. are mainly confined to the domain of linguistics; few have been carried out in the domain of politics. This methodological gap is even deeper in the field of conflict studies, where discourse ‒ as a tool that determines power relations in a political setting ‒ and its impact on conflict are relatively untouched.

René Lemarchand establishes one of the earlier works that connects discourse to political violence in his manuscript on ethnocide in Burundi.[4]René Lemarchand, Burundi: Ethnocide as Discourse and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). Lene Hansen’s work on the Bosnian War conflict discourse,[5]Lene Hansen, Security as Practice: Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War (Abingdon, OX: Routledge, 2006). Richard Jackson’s analysis on how discourse establishes state- society power relations in Africa,[6]Richard Jackson, “Violent Internal Conflict and the African State: Towards a Framework of Analysis,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 20, no. 1 (2002): 29-52, doi:10.1080/02589000120104044. Helle Malmvig’s incorporation of discourse analysis into sovereignty and intervention in Kosovo and Algeria,[7]Helle Malmvig, State Sovereignty and Intervention: A Discourse Analysis of Interventionary and Non-Interventionary

Practices in Kosovo and Algeria, reprint (London: Routledge, 2011). and Patrick M. Regan’s study of how outside powers instrumentalize discourse to justify intervention into civil wars[8]Patrick M. Regan, Civil Wars and Foreign Powers: Outside Intervention in Intrastate Conflict (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2002). establish the foundations of the literature on discourse and armed conflict. More-detailed studies such as Ivan Leudar et al.’s work on otherization discourses as a form of political violence,[9]Ivan Leudar, Victoria Marsland, and Jirí Nekvapil, “On Membership Categorization: ‘Us’, ‘Them’and‘Doing Violence’ in Political Discourse,” Discourse & Society 15, no. 2-3 (2004): 243-66, doi:10.1177/0957926504041019. or Stathis Kalyvas’ study on how discourse constructs action and identity in civil wars,[10]Stathis N. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006). can also be offered as literary precursors of the study presented in this article.

The relationship between political discourse and the Kurdish conflict is also an understudied area, and Turkey’s Kurdish question offers a rich case study with ample opportunities for diverse research agendas. This article holds the view that qualitative and quantitative approaches to discourse analysis are complementary in conflict analysis. Classical/mainstream discourse analysis data can be fed into appropriate statistical methods, especially with studies on institutional discourse over extended periods. Studies of legislative discourse are examples of the adoption of this two-tier methodological approach. The methodology offered in this article may provide future studies with a working model in terms of observing cognitive mechanisms and competing interests related to intra-state conflicts over extended periods. Furthermore, by expanding the works of Mesut Yeğen,[11]Mesut Yeğen, “The Kurdish Question in Turkish State Discourse,” Journal of Contemporary History 34, no. 4 (1999): 555-68. Cengiz Güneş,[12]Cengiz Güneş, The Kurdish National Movement in Turkey: From Protest to Resistance (Oxon, OX: Routledge, 2013) Jaffer Sheyholislami,[13]Jaffer Sheyholislami, Kurdish Identity, Discourse, and New Media (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Yusuf Çevik,[14]Yusuf Çevik, “The Reflections of Kurdish Islamism and Everchanging Discourse of Kurdish Nationalists Toward Islam in Turkey,” Turkish Journal of Politics 3, no. 1 (2012): 87-102. and Serhun Al[15]Serhun Al, “Elite Discourses, Nationalism and Moderation: A Dialectical Analysis of Turkish and Kurdish Nationalisms,” Ethnopolitics 14, no. 1 (2015): 94-112, doi:10.1080/17449057.2014.937638 on Turkish state discourse on the Kurds, this article offers discursive perspectives from all bands of the political spectrum in Turkey, the European Union (EU), and the US Congress (USC).

My hypothesis is that we can test the connection between political agenda and political ideology and the effect of this connection on the way a politician perceives and talks about a particular conflict. I argue that conservative politicians perceive intra-state conflicts primarily as terrorism or security problems, whereas liberal politicians talk about these conflicts within the context of democratic deficits and poor human rights standards. To test these hypotheses, I have carried out content analysis of legislative open-floor transcripts from the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA), European Parliament (EP), and USC (both the Senate and the House), on the Kurdish question through the conflict’s most intense, violent, and ‘busy’ period, from August 1990 to February 1999. Selection rationale for this period is based on time-series data from the Global Terrorism Database on Turkey-origin incident frequency perpetrated by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).[16]2. Methodology Discourse analysis can explore all levels and aspects of language, but here, we are concerned On defining conservatism and liberalism as they appear in this article, I rely on the following:

This study is crucially significant for two reasons, one methodological and one empirical. Methodologically, it introduces discourse analysis and quantitative methods into the domain of conflict psychology in a mutually supportive hybrid. Empirically, it addresses a surprisingly overlooked but central aspect of an otherwise saturated topic (the Kurdish question), which is: If we were to introduce a set of solutions, what exactly would it entail? I answer this question by recalling another severely overlooked truism: One cannot resolve a poorly defined question. Thus, I argue that the reason why the Kurdish question has remained unresolved for so long is that it has been misdefined by the Turkish state, which exclusively looked at the problem as one of security and terrorism, omitting other components that make up the problem. Rather than attempting to offer another subjective definition, this study aims to offer a mirror to these discursive preferences and constructions, prioritizing the empirical demonstration of these subjectivities in a comparative fashion. In that, the study is analytical and critical rather than descriptive.

2.Methodology

Discourse analysis can explore all levels and aspects of language, but here, we are concerned with semantics and lexicon. Lexicalization is a major domain of ideological expression and persuasion, as the well-known terrorist versus freedom fighter pairing suggests. When referring to particular persons, groups, social relations, or social issues, language users generally have a choice of several words, depending on discourse genre, personal context, social context, and socio-cultural context. This study adds to the field of discourse analysis by introducing the dimensions of time and frequency to examine how (whether) those discourses have changed over time in terms of context and rate of recurrence. These findings will help us examine the particular events chosen for debate in parliaments. Thus, discourse, as defined for the purposes of this study, is

a) strategic function (argument) and

b) a context within which an argument is constructed.

Within this framework, parts and phrases of a parliamentary speech are considered discourse if they are arguments (criticism-defense/support-opposition) and/or if those arguments are made within a specific context (human rights, democracy, ethnicity, etc.).

Speech-act theory introduces the concepts of illocutionary or performative acts, which regard communication as a factor affecting belief and construction of personal reality. Developed by John L. Austin, the illocutionary act concept asserts that speech is actually a performance, undertaken towards what Austin calls “conventional consequences” such as arguments, commitments, or obligations.[21]J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, ed. J. O. Urmson and Marina Sbisà, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975), 107 From this perspective, speech-act theory diverges from discourse theory, as the latter takes speech as a dependent variable – affected by structure – and the former takes it as an independent variable – affecting structure. Speech acts, therefore, distinguish between two types of communication: speech in order to express reality and speech in order to affect or alter it.

Austin identifies three processes of action beyond speech itself. The first is the act of utterance, which has three additional qualities: locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts. For example, when a Turkish parliamentarian utters the words: “There is no such thing as a Kurdish problem (A1). This is a problem of terrorism (A2),” he informs the audience that the assertion A1 is – in his view –empirically not true, whereas the A2 assertion – again, in his view – should replace the initial assertion since it carries a greater truth value. Of course (because of his/her subjective immersion into the context), the parliamentarian does not recognize that the truth-value being asserted is not reality but perception. Maybe less directly

– given the appropriate context – his/her statements may also be inferred as telling other parliamentarians to vote in favor of a security measure. With an inferential and contextual reading, parliamentarians must infer that given A2 is true, they are asked to support a bill or resolution in favor of increasing troop count in the emergency-measure provinces. The A2 assertion also aims to knock down other definitions of the “problem in the south-east” (since within this context, it is not defined as the Kurdish problem) such as human rights, democratization, or excessive force, and establish the supremacy of one verbal construction of a conflict’s nature over other constructions.

Different from discourse theory, which deals with macro-level communication, speech- act theory looks at micro-level communication (speech, dialogue). In that respect, speech-act theory is more technical than discourse theory, since the former looks into lexical, syntactic, and grammatical structures of communication. The importance of speech-act theory for the purposes of this study comes from its exploration of the three levels of speech: directness-indirectness, literal-nonliteral meaning, and explicitness-inexplicitness based on the context of communication. For example, when a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) says: “It is in the Turkish army where real power lies,” that statement can be regarded as a direct, literal, and explicit observation: the Turkish military has the real power. But from the perspective of democratic standards, the statement becomes an indirect, nonliteral, and inexplicit criticism, where an accusation of the Turkish democratic system is made about the excessive weight the armed forces exert on the functioning of a representative system and party politics. From that perspective, indirectness, nonliterality, and inexplicitness become important illocutionary tools in a communicative setting where restraints on speech are heavier. Such comments have been an important pattern in Turkish Parliament debates, especially where construction of the ‘Kurdish question as the Kurdish question’ was immediately inferred as recognizing Kurds as a separate entity within Turkey; a threat against the unitary character of the nation and against territorial integrity.

Previous literature on political linguistics looks at language either in terms of time (short-term event: speech act; versus longer-term phenomenon: discursive structures)[22]Philip R. Cohen et al., Intentions in Communication (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990); Herman Cappelen and ErnestLepore, Insensitive Semantics: A Defense of Semantic Minimalism and Speech Act Pluralism (Oxford, OX: John Wiley & Sons,

2008); Emanuel A. Schegloff, “Presequences and Indirection,” Journal of Pragmatics 12, no. 1 (1988): 55-62, doi:10.1016/0378-2166(88)90019-7. or power relations[23] Scott A. Reid and Sik Hung Ng, “Language, Power, and Intergroup Relations,” Journal of Social Issues 55, no. 1 (1999): 119-39, doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00108; Margaret Wetherell et al. eds., Discourse Theory and Practice: A Reader (London: SAGE, 2001); Pierre Bourdieu and John B. Thompson, Language and Symbolic Power (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991). (structure-agency debate). Moreover, even in the literature on belief and language, a body of beliefs or images is taken either as a dependent or an independent variable, without sufficient discussion of the relationship between speech act and discourse. This study, therefore, attempts to establish the link between speech and discourse, arguing that they are mutually dependent structures. Moreover, I argue that although speech acts do not immediately lead to policies, they affect discourses and linguistic constructions of images over an extended period of time and create belief systems and norms out of which decisions arise in the long run. From this perspective, a speech act ‒ during the time and space of its utterance – contains three versions of subjective time: past (affected by discourse), present (competing against other discourse candidates), and future (affecting discourse). Although a particular speech does not become policy in the long run, it becomes part of a discursive structure, and that discursive structure will either become the hegemonic discourse out of which policies arise or become a counter-hegemonic discourse, trying to overthrow the hegemonic discourse. In the latter case, the speech act will still affect policy by causing the hegemonic discourse to define itself along the lines of what the counter-hegemonic discourse is not, leading to policies in reaction to it.

2.1. Methodology step 1: data collection

Given the definition of discourse above, I assembled entire debate records from parliamentary sittings between January 1990 and December 1999. Most search results were read and sorted according to relevance. Debate sessions were considered relevant if they conformed to the following criteria:

2.2. Methodology step 2: data evaluation

The selected material was subjected to a second round of evaluation in which sentences and phrases were evaluated according to their discursive value, comprising

The content analysis carried out on all legislative open-floor deliberations on the Kurdish question in the three legislatures revealed ten major discursive contexts within which intra- state conflict was debated. These discursive contexts, made up of recurring speech acts that defined the essence of the Kurdish question and their corresponding ‘solutions,’ defined Turkey’s Kurdish question as one of the following:

The above six contexts were frequently used within all three legislatures. Four additional contexts were exclusive to the TGNA:

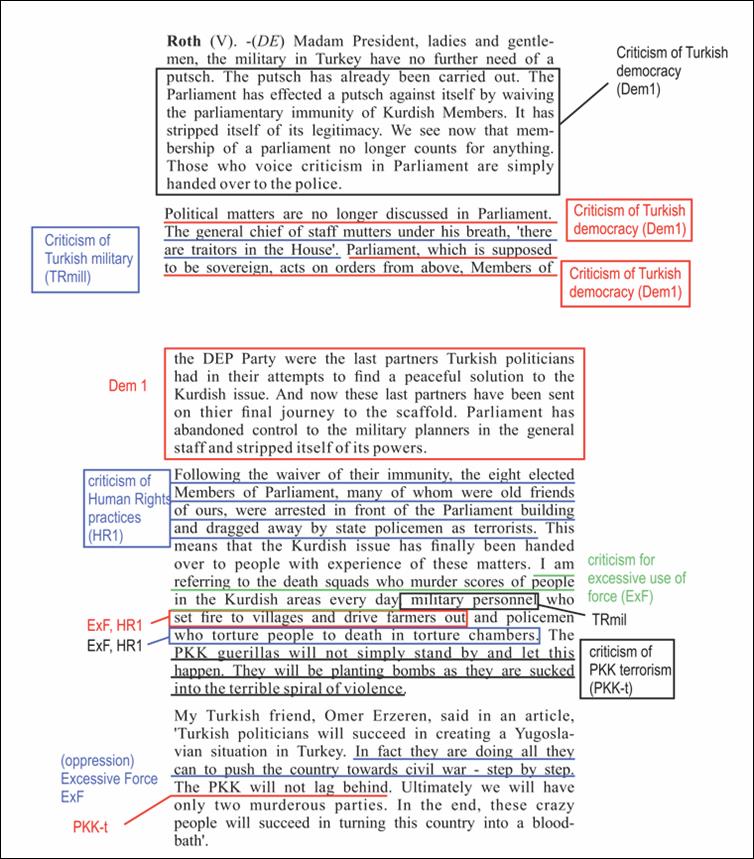

Figure 1 shows how such evaluations were made using German MEP Claudia Roth’s statement during the EP debate of March 10, 1994, in response to the arrest of Kurdish members of the Turkish Parliament.

Figure 1: Evaluation of EP speech by Claudia Roth (Germany - Green Party), March 10, 1994

These discursive contexts were then sorted according to:

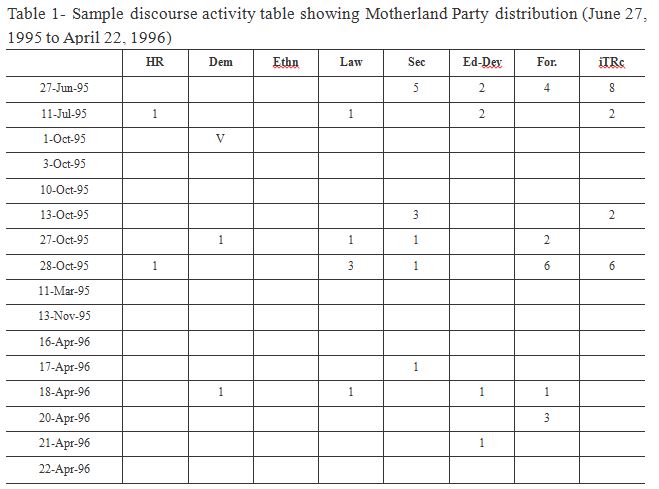

a. Party affiliation of the legislators: Who adopts HR arguments the most? Which political parties choose to talk about the Kurdish question within the context of terrorism and security? Is there an ideological bent to how a politician perceives and talks about the Kurdish question? Table 1 is a discourse activity chart for the Motherland Party (ANAP) of the Turkish parliament from June 27, 1995, to April 22, 1996

My hypothesis is that party affiliation and ideology matter most among leftist and/or liberal politicians. We can hypothesize that liberals and/or leftists express their ideological priorities ‒ human rights, democratization, etc. ‒ more readily than right-wing or conservative politicians, who mainly operate within the domain of agenda politics rather than ideology.

i. Country affiliation and the Kurdish Diaspora in the EP. European MEPs generally express the national interests of their respective countries vis-à-vis Turkey when it comes to debates on the Kurdish question. Greece, whose political relations with Turkey have been tense because of a number of diplomatic issues, has chosen to internationalize these disputes via EP debates on the Kurds. Germany, on the other hand, has been a significant arms supplier to the Turkish military, and the excessive force practiced by the latter has led German MEPs to protest Turkish-German military agreements. Other countries approach the issue within the context of their NATO commitments; the post-Gulf War context necessitated an air force buildup at the NATO base in southern Turkey. In addition, the presence of a significant Kurdish Diaspora in Germany, Austria, and France has led these countries to express in the EP the concerns of their highly politicized Kurdish constituencies.

iii. Constituency and voter pressure in the TGNA. Representing a Kurdish-majority constituency or coming from a predominantly Kurdish city are the main factors affecting agenda in the TGNA. The 13 predominantly Kurdish cities that have seen the most intense bursts of violence were under the jurisdiction of the Emergency Super- governorate, a special enforcement mechanism with expanded powers, from 1987 to

Following the content analysis findings, quantitative operationalization was necessary. The primary operationalization method involved counting and sorting the aggregate number of discourses according to their type. Another re-sorting was necessary, this time according to legislator, to analyze the discourse type and frequency of reference to the Kurdish question by party affiliation, caucus affiliation, and constituency. The rest of the article discusses these variances in quantitative terms.

3.Results

3.1. The European Parliament (EP)

In analyzing the EP discourse on the Kurdish question, we will first look at how agenda (country affiliation: which country an MEP represents) affects legislative discourse. Later, we will test whether party (ideology) affiliation has any effect.

3.1.1. Agenda: country affiliation

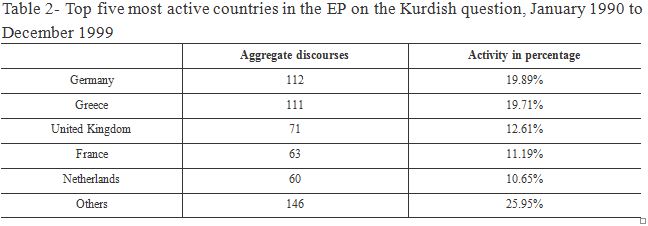

In the EP in the time period studied, there have been 563 references to the Kurdish question (total number of n = discourse; see Table 1). Agenda, as defined by country activity in the EP, can be measured in two ways. First, one can look at the total number of discourses adopted by each country, and second, at the total number of discourses in ratio to the country’s number of MEPs. The most active countries in terms of total number of n are shown in Table 2

These countries are followed by Italy, Belgium, Sweden, Austria, Spain, Ireland, and Denmark in descending order of n.

Two hypotheses may help explain the frequency for an EU country with regard to its MEPs’ speech activity on the Kurdish issue. The first is: MEPs of a country with a large Kurdish population speak more on the Kurdish issue.

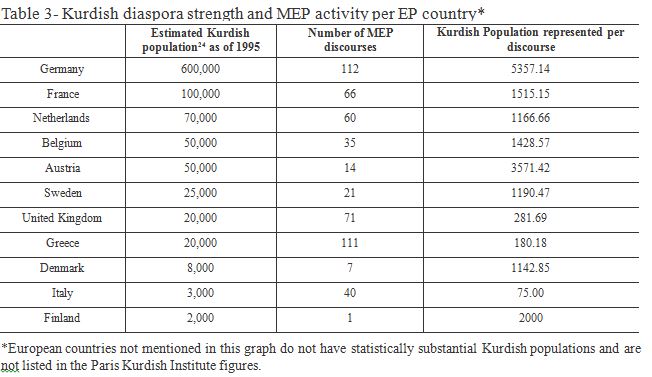

The size of Diaspora membership is strongly linked to electoral interest in constituencies; as MEPs are primarily representative of their constituents, the Kurdish population (Diaspora strength) is the most relevant data to be tested. To test this, the relationship between the dependent variable (aggregate number of discourses) and the independent variable (Kurdish population) must be measured. This finding will provide us with a general pattern within the EP with regard to this hypothesis, as well as outliers that render this hypothesis insignificant. The estimated numbers of the Kurdish population are collected from the Paris Kurdish Institute, and shown in Table 3. [24]These figures are taken from the Paris Kurdish Institute webpage on the Kurdish Diaspora. Estimates are as of October 2008: “The Kurdish Diaspora,” Fondation Institut Kurde de Paris, http://www.institutkurde.org/en/kurdorama/.

In terms of “Kurdish population represented per discourse” measurements, German MEPs (most notably Claudia Roth of the Green group) have produced most of the discourse on the Kurdish question, with their country hosting the largest Kurdish Diaspora in Europe. However, a hypothesis asserting that MEPs of countries with a large Kurdish population produce more discourses on the Kurdish question appears not to be true for the rest of the EU countries. Two of the countries that follow Germany in terms of MEP activity on the Kurdish question (Greece and United Kingdom) host two of the smallest Kurdish Diasporas in Europe, an estimated 22,000 Kurds each. These two countries are also runners-up in the “Kurdish population represented per discourse” measurements; however counterintuitively, Italian MEPs stand out as being the most representative of their country’s Kurdish Diaspora, representing 87.5 Kurds per discourse.

Therefore, the first hypothesis seems to be flawed: the size of the Kurdish Diaspora in an EU country does not necessarily affect its MEPs’ activities in the EP. Germany seems to support our hypothesis in the sense that German MEPs have produced the most discourses on the Kurdish question and is the country with the largest Kurdish Diaspora in Europe. However, the fact that Greek, British, and Italian MEPs have represented the smallest group of Kurds in their country per discourse they have uttered is evidence against this hypothesis.

The second hypothesis that may explain an EU country’s activity in the EP relates to the number of MEPs a country has:

Countries with more seats in the EP produce more discourses on the Kurdish question.

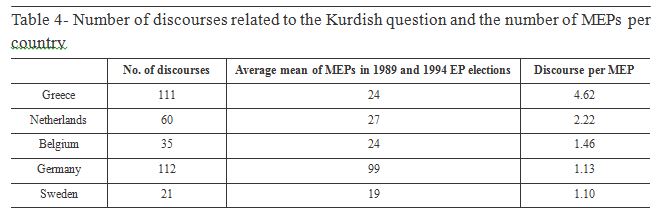

Put simply, more MEPs mean more speeches. To measure this hypothesis, we have to measure discourse per MEP, which will tell us how many discourses relating to the Kurdish question a country uttered divided by its seats in the EP. To do this, we look at the ratio of the total number of discourses (n) to the arithmetic mean (AM) of the number of the MEPs for each country in two EP election terms. The higher the discourse-per-MEP number, the more active that particular country’s MEPs have been, which will imply outlying special interests with regard to that country’s relation to the Kurdish question. According to this measurement, Greece tops the list (Table 4).

Greece has been the most active country in the EP on Turkey’s Kurdish question, just behind Germany on aggregate discourses (19.71% of total discourses) but way ahead on the discourse-per-MEP measurement (4.62 discourses per MEP).

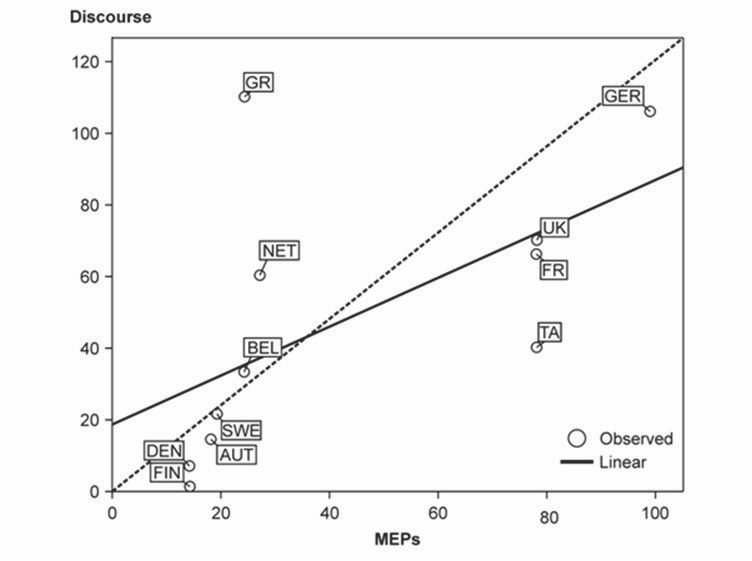

Curve statistics in Figure 2 also verify that Greek MEPs have been significant outliers of the trend and the most active members of the EP on a discourse-per-MEP measurement. The Greeks are followed by the Dutch, whereas Italian and Finnish MEPs stand out as the least active, based on the same measurement. Our second hypothesis is thus not perfectly valid either. While Greek MEPs again top the list in terms of discourses, Greece is one of the countries with fewer seats in the EP. This also applies to the Netherlands. Countries with more seats in the EP (France, the United Kingdom, and Italy) have been less interested in the Kurdish question compared to Greece and the Netherlands.

Figure 2: Discourse number per MEP activity: trends and outliers

A country-based analysis of EP discourses on the Kurdish issue provides us with few recurring patterns from which to derive a successful hypothesis, and thus supports our claim that agenda (as defined by country) does play some role in the EP. Among EU member countries, however, Greece is the outlier with regard to the Kurdish question in Turkey, topping country activity lists both in terms of “Kurdish population represented per discourse” and “discourse per MEP” measurements. It is safe to argue, then, that in the 1990s the EP became a forum in which Greece could internationalize its problems with Turkey by hijacking debates on the Kurdish question, aiming perhaps not so much to improve the situation of the Kurds, as to portray the Turkish state as an excessively militaristic and undemocratic entity. To conclude, Greek MEPs’ perceptions of the Kurdish question come out primarily as agenda-oriented.

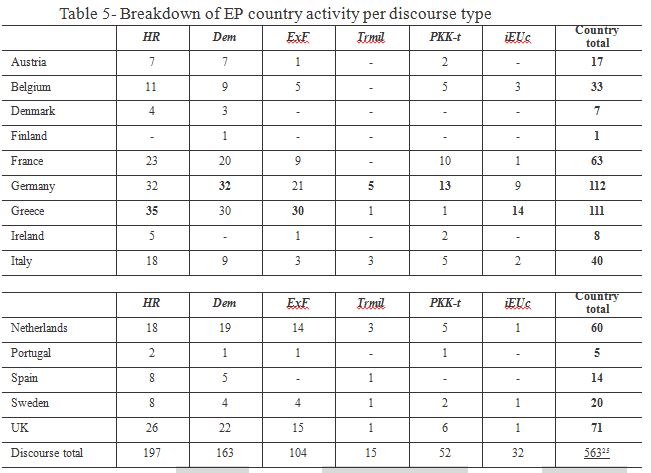

This finding is supported by looking at a breakdown of country discourses by discourse types, as shown in Table 5.

Key to terms: HR = Human Rights; Dem = Democracy/democratization; ExF = Criticism of excessive use of force; TrMil = Criticism of the Turkish military; PKK-t = Criticism of PKK/reference to terrorism; iEUc = Criticism of EU policy on the Kurdish question[25]Includes European Commission and Council of Europe discourses

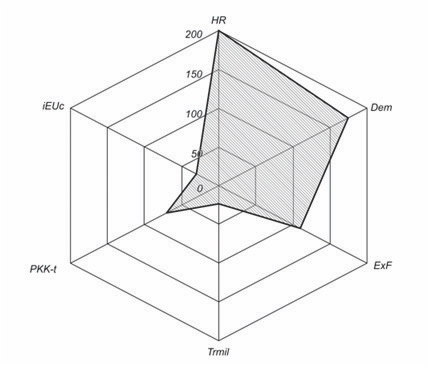

This overview shows that Greece was the most frequent critic of Turkey on the Kurdish question, especially within the HR and ExF discourses. In addition, Greek MEPs have criticized PKK violence less than other MEPs, while they are the most frequent critics of EU policy with regard to Turkey’s Kurdish question. Overall, the most frequently adopted discourse in the EP has been the HR discourse, followed by the Dem and ExF discourses. Although the ExF discourses are more frequent than the PKK-t discourses, the EP focused less on the Turkish military as the source of this excessive force and generally used arguments that were directed toward all the security forces involved. Greece emerges as the only country whose criticisms of the Turkish military overwhelmingly surpassed its criticisms of the PKK; the remaining EU countries appear to criticize the PKK more than they do the Turkish military. While Greece has been the most frequent critic of Turkey’s human rights practices, Germany was the predominant country in constructing the Kurdish issue within the context of democratization. Greece was the most frequent critic of Turkey’s security activities against the Kurds, criticizing the PKK only once in the 1990s. Germany and France, by contrast, were the most frequent critics of the PKK as a terrorist organization. Germany also criticized the Turkish army as the source of the Kurdish problem more frequently than any other country, perhaps because the Turkish military used German-sourced weaponry in the predominantly Kurdish southeast. A general view of the human rights- and democratization-focused EP discourses is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Radar graph showing comparative discourse type preference in the EP

No clear correlation exists between a particular MEP’s discourse activity on the Kurdish question and the number of Kurds living in the MEP’s country or the number of seats that a country has in the EP. Therefore, we will only analyze the legislature according to party affiliation (ideology), with the main finding of this section being that agenda played an important role in Greek MEPs’ perception and vocalization of the Kurdish question. While we cannot use the findings from our country-based analysis, this method is very valuable in terms of identifying outliers; that is, countries that either over- or under-performed on the basis of the main trends in the EP.

No clear correlation exists between a particular MEP’s discourse activity on the Kurdish question and the number of Kurds living in the MEP’s country or the number of seats that a country has in the EP. Therefore, we will only analyze the legislature according to party affiliation (ideology), with the main finding of this section being that agenda played an important role in Greek MEPs’ perception and vocalization of the Kurdish question. While we cannot use the findings from our country-based analysis, this method is very valuable in terms of identifying outliers; that is, countries that either over- or under-performed on the basis of the main trends in the EP.

3.1.2. Ideology: group activity

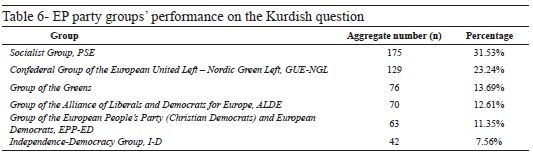

One of the primary hypotheses of this study is that party affiliation (an indicator of ideology for the purposes of this study) determines a parliamentarian’s discourse on the Kurdish issue. To test party activity within this context, a similar calculation to that used in the first section must be undertaken. Overall party activity in the EP, based on the total number of discourses (n) for all the groups (555), is presented in Table 6.[26]Excluding Council and Commission discourses, because these are technocratic bodies where party affiliation cannot be observed

To complement this list of party/group aggregate activity, it is important to look at the discourse-per-MEP measurement again, this time according to party affiliation. Member of European Parliament figures used in these calculations are the average mean of a group’s number of seats after the parliamentary elections in 1989 and 1994 (Table 7).

Table 7- Party groups’ average MEP numbers, based on 1989 and 1994 election results

|

1989 seats[27]For a breakdown of European Parliament seats based on party affiliation (1989-1994), see the Europe Politique website |

1994 seats[28]28 For a breakdown of European Parliament seats based on party affiliation (1994-1999) see the Europe Politique website |

Average MEPs |

Discourses per MEP |

|

|

GUE-NGL |

42 |

28 |

35 |

3.68 |

|

Greens |

30 |

23 |

26.5 |

2.81 |

|

I-D |

27 |

27 |

27 |

1.59 |

|

ALDE |

49 |

43 |

46 |

1.52 |

|

PSE |

180 |

198 |

189 |

0.92 |

|

EPP-ED |

155 |

184 |

169.5 |

0.37 |

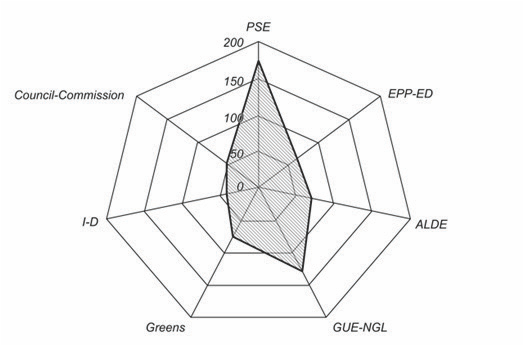

Members of the European Parliament from the European United Left-Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL) group have engaged in an average of 3.68 discourses on the Kurdish question, making them the most active on the Kurdish question in Turkey. When we compare EP’s aggregate party output on the Kurdish question, Figure 4 gives us a clear dominance of PSE and GUE-NGL groups.

Figure 4: Radar graph showing comparative party group activity (number of references to the Kurdish question) in the EP.

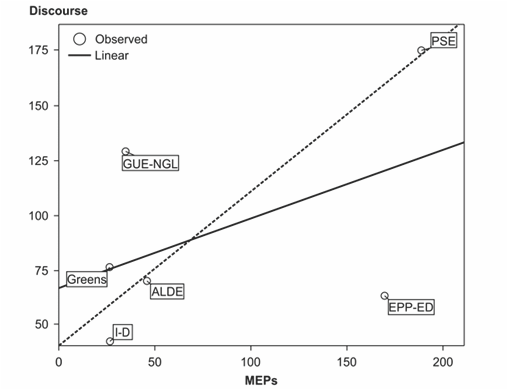

I stated earlier that the relationship between a country’s number of seats in the EP and that country’s activity on the Kurdish question was weak. A similar analysis can be made about the relationship between the number of MEPs in a group and that group’s corresponding aggregate discourse.

An initial hypothesis may be derived as follows; this hypothesis is tested in Figure 5 and

Table 8:

Figure 5: Trends and outliers in discourse-per-MEP measurement

Table 8- Discursive performance of EP political parties and European Council and Commission activity

|

HR |

Dem |

ExF |

Trmil |

PKK-t |

iEUc |

||

|

PSE |

61 |

58 |

33 |

4 |

16 |

3 |

175 |

|

EPP-ED |

22 |

14 |

7 |

4 |

12 |

4 |

63 |

|

ALDE |

25 |

22 |

11 |

5 |

7 |

0 |

70 |

|

GUE-NGL |

38 |

35 |

30 |

4 |

7 |

15 |

129 |

|

Greens |

15 |

25 |

19 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

76 |

|

I-D |

18 |

9 |

7 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

42 |

|

Council-Commission |

19 |

12 |

3 |

1 |

18 |

0 |

53 |

As the number of a group’s MEPs increases, so do the group’s aggregate discourses on the Kurdish question.

This hypothesis appears to be weak, but the groups that meet it are the European Socialist Group and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, whose discourses on the Kurdish question appear to be on par with their seats in the EP. The curve estimation is valuable because it allows us to see the outliers to the main trend: the Independence-Democracy and the Christian Democrat-European Democrat groups appear to be “uninterested” in the Kurdish question, whereas the Greens and Nordic Left have been the most active groups. The curve estimation analysis thus confirms our findings in the cross-tabulation.

The above overview shows that the European Socialists have constructed the Kurdish question within the context of HR, Dem, and ExF discourses more than any other group. It is also the group in the EP most critical of PKK violence. The Greens have identified the Turkish military as the cause of the Kurdish problem more often than any other group, whereas the United Left-Nordic Green Left has been overwhelmingly the group most critical of EU policies and the stance of European institutions on the Kurdish question. While all other EP groups have constructed the Kurdish question within the context of the HR discourse, the Green group has primarily referred to the Kurdish problem as a Dem issue. The Nordic Green Left also constructed the Kurdish question as an ExF problem far more than any other group in the EP as a percentage of total discourses adopted per group. Council and Commission members have also constructed this problem as an issue primarily of HR and then Dem. These bureaucratic bodies seldom referred to the ExF dimension, however, and regarded the Kurdish question essentially as a PKK-t problem, the second most common type of discourse adopted by the Council and Commission.

The European Parliament attempted to be careful not to condemn the PKK more than it did Turkish security practices. In general, the European Parliament adopted critical discourses towards Turkish security forces (without distinguishing between the police, military or gendarmerie) 103 times, making it the third most frequent discourse adopted, at 19.3%. This may at first appear higher than cases where Parliament criticized the PKK (referring to it as a “terrorist organization” or condemning its methods), which constitute 9.4% of the discourses. However, discourses that criticized the Turkish military directly for its human rights abuses or excessive use of force are much lower (1.5%) than those criticizing the PKK.

Compared to the MEPs, the Commission and Council can generally be seen as favoring Turkey on the Kurdish issue. While they criticized PKK terrorism (18 in total) much more than Turkish army abuses (three in total), they were less critical and more encouraging in their human rights-democracy discourses. Moreover, although the Council and Commission adopted discourses that condemned PKK terrorism (eight and 10 times respectively, they did not specifically target the Turkish military and conveyed their worries on excessive force in general wording.

The difference in discourses between the Parliament and the Council-Commission stems from the age-old tension between elected representatives and the executive bureaucracy; the Roman Senate and the Consul. Although an apparent reason for this difference is the raison d’être of parliaments and bureaucracies – where parliaments emphasize liberties, freedom of speech, and individualism, and bureaucracies emphasize state security, manageability, and realpolitik – another, less explicit reason for this difference is the essence of politics: the struggle against power in order to assume power. The difference between the European

Parliament and the Council-Commission in the Turkish debate is not because Parliament was more sensitive towards ethnicity, but because Parliament had been in a constant push for more say over European external affairs. Therefore, by adopting a different discourse than the bureaucratic branches, Parliament attempted to gain a foothold on arguably the most important item regarding the EU’s external relations – Turkey – and arguably the most critical issue in Turkey – the Kurdish question.

The first hypothesis I proposed for the EP is somewhat valid here. Ideology (measured by party affiliation) does play an important role in terms of the discursive construction of the Kurdish question. Two of the leftist groups in the EP (Nordic Greens and Greens) share the discursive pattern of emphasizing Turkish security force violations and playing down PKK terrorism, whereas the center-right European People’s Party referred less to Turkish military excesses and constructed this issue more within the domain of PKK terrorism. The data thus validates my hypothesis: As an MEP’s position approaches the political right, she/he constructs the Kurdish question increasingly within the state discourse (terrorism, territorial integrity, perpetuation of the state, and security). If an MEP’s position approaches the political left, on the other hand, she/he constructs the Kurdish question increasingly within the context of liberties and emancipation (human rights, democracy, state violence, and identity recognition).

That said, there is no clear pattern on data that can validate the hypothesis regarding country affiliation and the Kurdish discourse. We can nevertheless infer much from looking at outliers to test our hypothesis. Although Germany produced the most discourses on the Kurdish question in Turkey, this accords with our test hypothesis because Germany has the largest Kurdish Diaspora in Europe and the largest number of MEPs in the EP. It must be acknowledged, however, that Claudia Roth, the chairperson of the Green group, produced a great majority of German discourses on the Kurdish question in Turkey, so Germany’s dominance in the EP on this topic owes more to Roth’s activism and her constituency than to Germany’s sensitivity to the Kurdish question.

We can infer from this analysis that Kurdish discourse in the EP as well as criticism of Turkey in the 1990s was shaped by the statements of Greek MEPs of the Nordic Green Left and German MEPs (most specifically Claudia Roth) of the Green group. To conclude, it was mostly ideology and party affiliation that determined how an MEP ‘talked about’ the Kurdish question in Turkey in the EP, while country affiliation had a lesser influence on the discourse (with the slight exception of Greece). Later in this study, I will compare the EP’s discourse on the Kurdish question with that of the USC and TGNA.

3.2. The United States’ Congress

In this section, we will look at how the discourse on the Kurdish question in Turkey was shaped in the USC between 1990 and 1999 by separately analyzing three lines of demarcation: membership in the Senate or the House of Representatives, party affiliation, and caucus membership.

3.2.1. Ideology: Democrats vs. Republicans

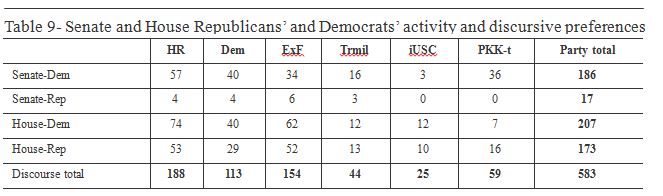

The primary fault line of analysis in the USC is party affiliation. For our analysis, I have adopted a discourse count-and-sort methodology similar to that in the above section on the EP (Table 9).

As Table 8 shows, the House of Representatives was the most active floor for the Kurdish question in Turkey, with an aggregate 380 discourses, as opposed to 203 for the Senate. We can see that Democrats dominate in the Senate, with 186 of aggregate discourses to the Republicans’ 17. Just as Claudia Roth single-handedly produced the majority of German discourses in the EP, Senator Dennis DeConcini (D-AZ) generated the overwhelming majority of Senate Democrats’ discourses. One can argue that through the 1990s, Senator DeConcini shaped the Senate narrative on the Kurdish question in Turkey. Although Democrats have also been active in the House of Representatives, party activity is more balanced there than in the Senate; House Democrats generated 207 of the discourses to the Republicans’ 173. Figure 6 shows the discursive priorities of the USC through 1990-1999:

Figure 6: Radar graph showing aggregate Congressional discursive preferences in defining the Kurdish question

The USC constructed the Kurdish problem primarily within the context of the HR discourse, both within the Senate and the House. Democrat members of the House and Senate have been the most dominant advocates on HR; the topic was also the most frequently adopted discourse of Republican representatives in the House. The second most frequently adopted discourse type was ExF, which deviates from the pattern in the EP, where Dem discourses were the second most frequently adopted. Republican representatives took the ExF position almost as often as HR discourses; ExF was the most frequently used argument of the generally inactive senators of the Republican Party. One can infer from this pattern that Republican members of Congress were more concerned about the ExF aspect of the Kurdish question, seeing it primarily as an issue of unnecessary violence. While constructing the Kurdish question within the context of Dem discourse was the third most frequent tendency in Congress, it was the second choice of discourse for Democratic senators, behind HR. Democratic senators were the most critical of the PKK as a terrorist organization, and Republican senators did not refer to the organization at all. After Republican senators, Democratic representatives were the least critical of the PKK and the most critical of Turkey’s military approach. Democratic representatives of the House were also the most critical group of US policy, the president, and the executive branch on the Kurdish question; Republican senators refrained from any such criticism.

United States’ Congress discourse on the Kurdish question is shaped not by party affiliation but by individual interest, as we shall see in the following section. There was a considerable amount of discourse concentration among certain members of Congress, more so than in the EP and, as we shall also see later, than in the TGNA, to the extent that a handful of members of Congress were the primary sources of Congressional discourse on the Kurdish question. This finding renders a party-based discourse analysis unimportant and raises the need to focus on individuals, narrowing the level of analysis down to agency.

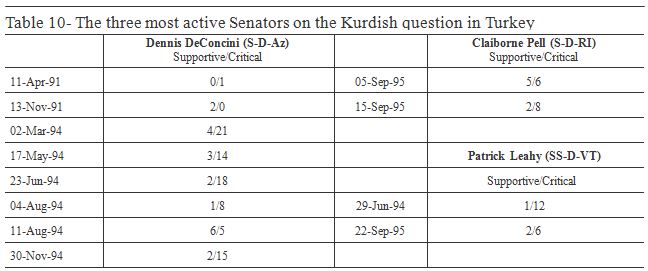

In the US Senate, the most active figure on Turkey’s Kurdish question was Dennis DeConcini, the Democratic senator from Arizona, who served between 1977 and January DeConcini produced half (50.2%) of the discourses in the Senate and 17.49% of the entire Congressional output on the Kurdish question. Other prolific senators on the Kurdish issue were Claiborne Pell (D–RI) and Patrick Leahy (D–VT) (Table 10).[29]S = Senate, H = House of Representatives, D = Democrat, R = Republican. Final acronyms indicate legislators’ states.

As we can see observe from Table 9, the most active senators produced “pro-Turkish” discourses often to encourage or praise a reform process. On the basis of the aggregate number of discourses, DeConcini was the most approving senator of Turkey as well as being its most frequent critic. However, Claiborne Pell generated the highest proportion of approving discourses (one-third of her total discourses).

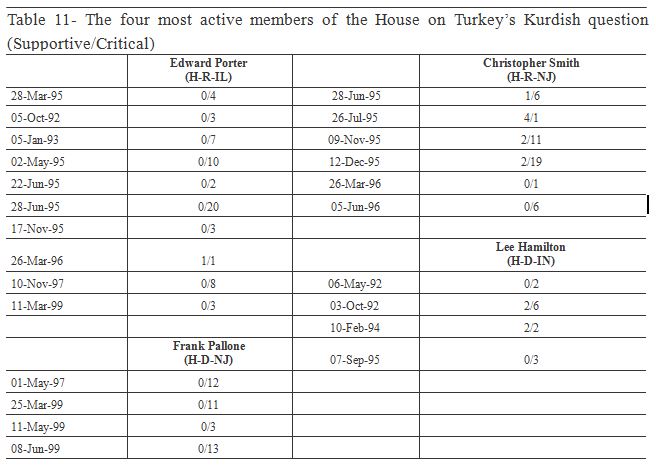

While the Democrats dominated the Senate and House discussions on Turkey’s Kurdish question, two Republican members were the most active individual figures in the House. Table 11 shows that Edward Porter (R–IL) emerged as the most active representative in the House (58 discourses) and Christopher Smith (R–NJ) was almost equally as active (57 discourses). They are followed by two Democratic representatives: Frank Pallone (NJ) and Lee Hamilton (IN).

Table 11 shows that while the most active senators used a combination of discursive ‘carrots and sticks,’ the representatives’ statements tended more toward criticism. The most critical senator was Edward Porter (R-IL), who was also the most frequent participant in debates on the Kurdish issue. Porter produced 33.52% of Republican statements on the Kurdish issue in the House of Representatives. The Republican runner-up, Christopher Smith (NJ), adopted slightly more supportive positions than Porter did, which formed 15.78% of his discourses. The third most active representative of the House (also the most active Democratic representative) was Frank Pallone (NJ), who was also the only representative in the list to make no positive reference to Turkey’s policies on the Kurdish question. Another active representative, Lee Hamilton (D–IN), was the most pro-Turkish among the most anti- Turkish, whose approving discourses constituted 23.52% of his total references.

Our hypothesis that party and ideology are the primary determinants of parliamentary discourse appears to be invalid for the USC because criticism and praise were bi-partisan and equally present in the Senate and the House. Given that party affiliation is not a statistically significant way of explaining Congress members’ activity on the Kurdish issue, we need to seek a different connection between the various members of the Senate and the House and the Democratic and Republican parties.

3.2.2. Agenda: caucus affiliation

As primary political identity (party affiliation) does not yield a conclusive pattern to explain discursive preferences, a second layer of identity (caucus affiliation = political agenda) should be introduced. Our second hypothesis thus states that Congressional caucus memberships (agenda) are the main influence on a congressperson’s approach to the Kurdish question. Based on suggestions received during the interview phase of this research, we test the Congressional membership of three caucuses: Human Rights, Hellenic, and Armenian. We examine in Table 12, whether (how) membership in these caucuses corresponds to the percentage of a congressperson’s critical discourses, based on a list of members who have spoken on the Kurdish question more than once in the 1990-1999 period

Table 12- Members of Congress active in debates on the Kurdish question and their affiliation with Human Rights, Armenian, and Hellenic caucuses303132

|

HR[30]Founded in 1983 |

Armenian[31]Founded in 1995. |

Hellenic[32]Founded in 1996. |

% of critical discourses |

|

|

Edward Porter |

+ |

- |

- |

98.20% |

|

Christopher Smith |

+ |

+ |

- |

84.20% |

|

Frank Pallone |

+ |

+ |

+ |

100% |

|

Lee Hamilton |

- |

- |

- |

76.40% |

|

Carolyn B. Maloney |

+ |

+ |

+ |

100% |

|

Elizabeth Furse |

- |

- |

- |

100% |

|

George Gekas |

+ |

+ |

+ |

100% |

|

James Bunn |

- |

- |

- |

0% |

|

Michael Bilirakis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

100% |

|

Peter John Visclosky |

+ |

+ |

+ |

100% |

|

Richard A. Zimmer |

- |

- |

- |

100% |

|

Steny Hoyer |

+ |

+ |

- |

100% |

The list shows that while appraisal/criticism dynamics were more fluid in the Senate, discourse within the House of Representatives was rigid, either entirely critical or entirely supportive. Moreover, with the exception of Lee Hamilton, all three senators were members of the Human Rights, Hellenic, and/or Armenian caucuses. In the House of Representatives, five of the seven representatives whose discourses were entirely critical were members of one or more of the three caucuses analyzed here; four of these representatives were members of all three caucuses. James “Jim” Bunn is the only non-critical representative, and he was not a member of any of these caucuses.

The human rights discourse in Congress had two dimensions; one focused on the situation of Kurds in Iraq, and the other focused on Kurdish rights in Turkey. Congress was overwhelmingly critical of Turkish practices on both fronts, and not even Turkish contributions to Operation Provide Comfort (OPC)[33]OPC was the name of the no-fly zone enforcement operation run by the United States Air Force through 1991-1996 to prevent Iraqi jets from harassing Kurdish refugees trapped close to the Iraqi-Turkish border. could disperse a strictly critical stance in either the House or the Senate. In terms of Kurds in Iraq, Congress was critical of what they perceived as a lack of willingness by Turkey to aid Kurdish refugees fleeing Saddam Hussein’s army at the end of the Gulf War. After the Gulf War, Congress was critical on what they thought to be Turkey’s restriction of international aid and the access of the Red Cross into northern Iraq, as well as reports on Turkish army misconducts during cross-border operations, such as burning and evacuating Iraqi villages. With respect to Kurds in Turkey, Congress emphasized illegal killings, torture, and disappearances under detention. Village burnings and evacuations were also a part of the human rights discourse in Congress, and in some instances certain congresspersons referred to such misconducts as “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide.” Human rights discourses were frequently adopted to back up arguments in favor of cutting or restricting aid to Turkey, as well as the sale of military hardware. The general sense in Congress was that Turkey had been undertaking human rights abuses in a systematic manner and such approaches were pursued as state policy. Some congresspersons (such as Bob Filner) even initiated off-Congress efforts, such as fasting protests in front of the Capitol in order to attract Congress attention to the abuses in Turkey and Iraq. In many ways, Congress discourses varied little since most representatives were usually critical of Turkey, almost never voicing praise or encouragement about constitutional changes, human rights trainings within the military, or other positive steps taken. Such almost non-existent mobility in discourses suggests that congressional positions on human rights were predetermined through lobbying efforts and other affiliations; an overwhelming majority of the members of the Congress were either rigidly ‘anti-Turkish’ or staunchly ‘pro-Turkish,’ with extremely rare cases of cross-argumentation.

In terms of the democracy-democratization discourse, congressional statements were somewhat more fluid than those made on human rights. For example, while certain congresspersons were rigidly anti-Turkish, some (such as DeConcini) actually praised Turkish democracy in rare instances, such as after fair elections or amendments made to Turkey’s notorious Article 8 of the anti-terror law.[34]This refers to a revoked article, which used to allow prosecution of statements that are deemed ‘propaganda against the indivisibility of the state’. Due to a very broad and unclear definition of what specific statements were prosecuted, this article was used as a way of restricting opposition or criticism of state practices on the Kurdish question One possible reason for these statements could be Turkey’s role as a uniquely democratic (although troubled) country in an overwhelmingly authoritarian and fundamentalist neighborhood. Indeed, DeConcini himself conveyed his hope that “Turkish democracy [...] can serve as a model for its less democratically inclined neighbors [...].”[35]137 Cong. Rec. S,31551 (November 13, 1991) (statement of Sen. DeConcini). However, with the intensification of the insurgency and the democratic restrictions that followed, Congressional discourses turned completely critical. By the mid-1990s, Turkey, once a success story of American foreign democratization policies, was increasingly compared to the repressive Soviet regime in terms of restrictions on free speech. This critical tone heightened after the arrest of Kurdish parliamentarians of the Turkish Assembly, which led Congress to question whether democracy existed at all in Turkey, rather than arguing on its quality. Still, it is possible to frame such ‘negative’ discourses as inclusionist because Turkey’s democracy was debated within the context of Turkish obligations to the treaties and conventions that are part of the Western system, as opposed to certain exclusionist discourses in the European Parliament that regarded Turkey outside of the Western system of beliefs and conducts. By 1997, however, Turkish democracy was already being likened to that of ‘non-Western’ countries such as China, and the fact that the executive branch of the US government was still cooperating very closely with Turkey elicited Congressional statements that the executive branch was encouraging Turkey in its repressive policies.

The excessive-force discourse was one of the most frequent discourses adopted in Congress in the time period analyzed. Such discourses focused on perceived Turkish security heavy-handedness and the inability (or unwillingness) to distinguish between terrorists and non-combatants in cross-border operations, as well as police measures within Turkey. The biggest criticism of the Turkish military in this respect was its usage of heavy weaponry such as cluster bombs and napalm against PKK bases surrounded by villages, which resulted in more civilian casualties than destroyed PKK targets. As the US and Turkey were major security partners and the US had provided almost 80% of Turkish arms,[36]For a yearly breakdown of US military sales to Turkey, see the Federation of American Scientists webpage on Turkish arms acquisitions, accessed May 4, 2009, http://www.fas.org/asmp/profiles/turkey.htm. Congress was extremely critical of President Clinton and the executive branch for authorizing the sale of advanced weaponry to Turkey. The second line of criticism of the Turkish army was not distinguishing between civilians and PKK operatives. Most congresspersons believed that by burning villages and expelling their inhabitants (who then became potential recruits for the PKK), the Turkish army was creating conflicts that could have been avoided. The ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘genocide’ arguments were also frequently tied to this discourse, and the arguments cited many similarities between the events of 1915 against the Armenians and the invasion of Cyprus.

To conclude, although party and ideology were the primary predictors of how legislators spoke about the Kurdish question in the European Parliament, neither party membership nor membership in the House or Senate had any correlation with legislators’ approach to the Kurdish question in the US Congress. I believe that the primary influence over legislative discourse in the USC was legislators’ agenda (reflected by their caucus membership, constituency, or origin of campaign contributions), and within this context, Greek and Armenian interest groups (rather than Kurdish ones) were hugely influential in USC discourse on the Kurdish question. In many ways, one can argue that Greek and Armenian interests exerted heavy influence on US-Turkish relations in the 1990s by hijacking the topic of the Kurdish question and creating connections between apparently unrelated issues, such as the Kurdish question, the invasion of Cyprus, the Armenian genocide, US support for Turkey’s EU membership, and US arms sales to Turkey. Congressional discourse thus had a heavier Greek-Armenian bias than a genuine Kurdish or HR perspective, which reflects the influence that donations have in shaping political agenda. In arguing so, however, I am not dismissing the effect of ideology on a congressperson’s choice of agenda and the source of his/her donations. The findings I report here are merely what we can observe through available data on Congressional activity on the Kurdish question

3.3. Turkish Grand National Assembly

As the political body for the host country of the conflict in question, the TGNA is critical to the study of conflict perception and discourse. Analyzing the TGNA allows us to identify similarities and differences in perception between the host of the conflict and those of outside observers. Does the country experiencing domestic conflict see the problem differently than outside observers do, or are there similarities? Here, we deal with how Turkish political- legislative discourse contextualized its internal problem and whether ideology or agenda exerted a more influential weight on discursive construction. I will test whether and (how) party affiliation (ideology), constituency (agenda), and membership of a governing or opposition party affected a legislator’s discourse on the Kurdish question in Turkey. We expect a similar trend to those observed in the two previous legislatures; namely, that conservative politicians define the question as a security and terrorism problem, and liberal politicians focus on the humanitarian and emancipatory aspects.

3.3.1. Ideology: party affiliation

Ideology in the Turkish National Assembly through the 1990s can be summed up as follows:[37]As Turkish political party ideologies are often fluid and difficult to determine fully from their manifestos, these ideological definitions were made by the author, with the help of Prof. Hasan Bülent Kahraman (Kadir Has University) and Prof. Fuat Keyman (Sabancı University).

Within this context, I show in Table 13 and Figure 7 whether our previous finding on the effect of party ideology on legislative discourse in the EP is also valid for the TGNA

Table 13- Political parties’ performance and discursive preferences in the TGNA

|

HR |

Dem |

Ethn[38]Please note new discursive contexts exclusive to the TGNA: Ethn = the argument that the Kurdish issue is essentially an ethnic identity question; Law = legalistic discourses; Sec = security discourse; Ed-dev = the argument that the Kurdish question emerges from a lack of education and development in the region; For = emphasis on “foreign dark powers” or foreign instigation; iTRc = criticism of Turkish policy on the Kurdish question; SF-VG = criticism of security forces or paramilitary village guards’ brutality toward the Kurds. |

Law |

Sec |

Ed-Dev |

Foreign |

iTRc |

SF/VG |

ExF |

Total |

|

|

ANAP |

15 |

15 |

8 |

2 |

10 |

36 |

13 |

48 |

53 |

12 |

212 |

|

DSP |

9 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

16 |

25 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

74 |

|

S-C/HP |

25 |

22 |

13 |

20 |

18 |

20 |

20 |

12 |

25 |

44 |

219 |

|

RP |

16 |

15 |

14 |

8 |

36 |

23 |

91 |

31 |

22 |

17 |

273 |

|

DYP |

8 |

6 |

7 |

4 |

22 |

22 |

32 |

14 |

5 |

0 |

120 |

|

MHP |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

10 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

29 |

|

State |

13 |

14 |

5 |

17 |

50 |

28 |

45 |

1 |

8 |

0 |

181 |

|

Total |

88 |

71 |

51 |

52 |

152 |

147 |

236 |

111 |

120 |

74 |

1108 |

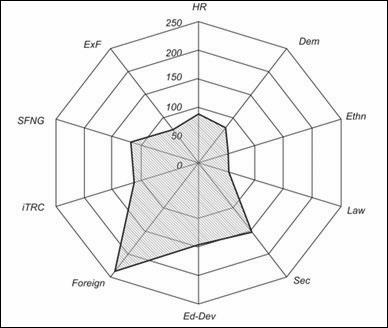

Figure 7: Radar graph showing TGNA discursive preferences on the Kurdish question

From Table 13, we see that in aggregate discourses the RP was the most active party on the Kurdish question (273), followed by the SHP-CHP (219) and the ANAP (212). However, because the 1990s witnessed one of Turkey’s most politically fragmented periods, when the TGNA’s composition frequently changed due to collapsing coalition governments, we must verify this activity using a ‘discourse-per-MP’ measurement. Moreover, while the total number of MPs was 450 until 1995, it was raised to 550 MPs thereafter.

Based on the average MP numbers,[39]Data derived from the TGNA webpage (https://global.tbmm.gov.tr/) on parliamentary composition by year. in Tables and 14 and 15 I show a discourse-per-MP measurement, as I did for the EP

Table 14- MP numbers of the main political parties in the TGNA across three general elections

|

1991 |

1995 |

1999 |

Average |

|

|

DYP |

178 |

135 |

85 |

132.6 |

|

ANAP |

115 |

132 |

86 |

111 |

|

SHP-CHP |

88 |

49 |

0 |

45.6 |

|

RP |

62 |

158 |

111[40]The Welfare Party was closed down in January 1998, after the military intervention in February 1997, which accused the party of anti-secular activities. After its closure, most party members switched over to the Virtue Party in December 1998, and then split between the Felicity Party and the Justice and Development Party in June 2001. The Felicity Party was closed down in 2001 for the same reason. The figure here refers to the Felicity Party. |

110.3 |

|

DSP |

7 |

76 |

136 |

73 |

|

MHP |

0 |

0 |

129 |

43 |

Table 15- Number of discourses in proportion to average number of MPs in the TGNA to determine party activity on the Kurdish issue40

|

Number of discourses |

Average number of MPs |

Discourse per MP |

|

|

DYP |

120 |

132.6 |

0.905 |

|

ANAP |

212 |

111 |

1.909 |

|

SHP-CHP |

219 |

45.6 |

4.802 |

|

RP |

273 |

110.3 |

2.475 |

|

DSP |

74 |

73 |

1.013 |

|

MHP |

29 |

43 |

0.674 |

When we level out party discourses according to their average number of seats in the TGNA through 1991-1999, we find that MPs of the left,[41]In our case, the center-left. The military coup of 1980 eradicated far-left groups and outlawed such ideologies, requiring any leftist party to redefine its ideology along Kemalist lines. Thus, all the center-left parties had to adopt a certain level of Kemalist discourse to function within the political system so as not to be marginalized by the establishment. Center-left parties were thus as left as Turkey could go in the 1990s particularly the SHP (whose ranks joined the CHP after 1995), were the most active on the Kurdish question in Turkey. They were followed by members of the RP and the ANAP. Thus, our hypothesis on ideology and discourse appears to be partially valid for the TGNA. It is true that the most active MPs belonged to the SHP-CHP, which are both center-left parties, but the runner-up was the right- wing/conservative RP, followed by the center-right ANAP. The TGNA also conformed to the trend in the EP (as you go left-liberal in the political continuum, there is more interest in the Kurdish question, and if you go right-conservative, there is less interest), as shown by the disinterest of the right-wing MHP, the least active party, measured both by aggregate discourses and discourse-per-MP measurements. However, the political left-right pattern was not clear in the TGNA. Although the most active party belonged to the center-left and the least active party belonged to the right, this does not necessarily validate the claim that as one goes left in the political continuum, there is more interest in the Kurdish question, or vice versa. Another party of the center-left, the DSP, was among the least active parties in the TGNA according to the discourse-per-MP measurement, while the right-wing RP was among the most active.

In the following section, I present and test another hypothesis, which will enable us to better see these discursive fault lines.

3.3.2. Agenda: constituency

In the previous section, I discussed how ideology and party affiliation shaped MPs’ discourses in the TGNA through the 1990s. Here, I will introduce a second hypothesis with regard to a legislator’s agenda, shaped by constituency:

If a legislator represents a district (city) that is under emergency law, she/he will construct the Kurdish question within the context of emancipation and rights, whereas if a legislator does not represent such a district, she/he will define the Kurdish question as a security and territorial integrity problem.

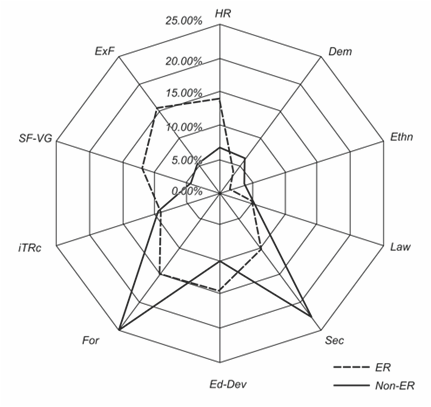

Cities in south-eastern Turkey (Diyarbakır, Mardin, Siirt, Batman, Şırnak, Van, Hakkari, Bingöl, Muş, Tunceli, Bitlis, and Elazığ) were brought under emergency law and the jurisdiction of the Emergency Super-governorate in 1987 by a decision of the Council of Ministers. Here, I compare discourse preferences of the parliamentarians representing these cities with representatives from the rest of Turkey. Table 16 and Figure 8 show discourse types classified according to whether the representative comes from the emergency region (ER) or not (Non-ER).

Table 16- Aggregate discursive output and preference among emergency region and non- emergency region MPs

|

HR |

Dem |

Ethn |

Law |

Sec |

Ed-Dev |

For |

iTRc |

SF-VG |

ExF |

Total |

|

|

ER |

28 |

7 |

3 |

11 |

21 |

29 |

30 |

18 |

24 |

31 |

202 |

|

Non-ER |

66 |

62 |

37 |

52 |

222 |

99 |

240 |

94 |

45 |

51 |

968 |

Figure 8: Radar graph comparing emergency region MPs’ discursive preferences with those of MPs from the rest of the Turkey

We can see that ER representatives provided 17.26% of the discourses in the TGNA on the Kurdish question. While ER representatives understandably focused on ExF, SF-VG, and HR, they were critical of foreign countries (For) and pointed to the underdevelopment of their region (Ed-Dev) with the same degree of frequency. Non-ER representatives, on the other hand, focused mainly on For and Sec discourses, paying no more attention to the Ethn, ExF, and SF-VG aspects than they did to Dem and Law.

In terms of the human rights discourse, the TGNA was divided. On the one hand, there was a sub-discourse in which parliamentarians argued that Turkey respected human rights, even of the Iraqis across the border, and on the other hand, a sub-discourse that converged with the critical discourses of the EU Parliament and US Congress. One conservative sub-discourse on human rights focused on the safeguards in the Turkish legal system that prevent torture and other abuses, arguing that it was impossible for such abuses to exist in Turkey. The second conservative sub-discourse pointed to human rights abuses in other countries, asserting that there was nothing wrong with the Turkish approach to the Kurdish question. Further, human rights monitors or organizations were constructed as ‘separatists’ within the conservative discourse, who helped the propaganda activities of the PKK. The primary liberal discourse on human rights criticized the conservative argument that pointed to the legal safeguards in the constitution and argued such that an easy escape prevented any conclusive settlement on identifying the torturers. The second line of liberal discourse argued that torture was systematic and now an everyday occurrence with prisoners and convicts. The third line of liberal discourse criticized the security force’s excuses about torture (either that it was necessary because of security concerns, or a tool to maintain order), arguing for the necessity of establishing governmental institutions that could provide an alternative channel of observation.

Discourses on the democracy aspect of the Kurdish question also showed variance. The first line of liberal discourse focused on the danger of granting electoral rights to the constituents of evacuated villages, arguing in favor of adding them to the constituencies of the cities they had migrated to. A conflict between the liberal and conservative definitions on democracy was also explicit in terms of recognizing Kurds as Kurds. While the liberal line constructed democracy within the context of free expression and recognizing minorities, the conservative discourse on democracy focused on the equality and Turkishness of all citizens. The first line of distinctly conservative arguments favored limiting democracy, since too much of it would lead to the disintegration of the country. The liberal variant of this argument favored debate and free discussion of all ideas (even separatist ones) even though one might not identify with them. The crux of this distinction appears to be the acceptance of two different versions of democracy, one favoring the early-twentieth-century European version, which emphasizes equality and citizenship, and the second adopting the post- modern definition, which emphasizes recognition, political identity, and free expression. Based on this difference, the Emergency Measures or Emergency Super-governorships were constructed as ‘democratic’ within the conservative discourse (since they tried to establish security equally to all citizens), whereas within the liberal discourse they were considered exceedingly ‘undemocratic’ (since they had bypassed Constitutional rights and engaged in a wide array of counter-terrorism methods, from limiting freedom of expression to authorizing arrests without indictment).

Liberal parliamentarians generally adopted excessive-force discourses. While some parliamentarians constructed security force abuses as ‘state terrorism,’ others constructed it within the context of ‘government incompetence.’ Village burnings were an important topic of excessive force arguments. In terms of such burnings, the liberal argument pointed to the utility of villages for PKK needs such as supplies or accommodation, arguing that the PKK would not want villages to be burned, an argument sharply contrasting with the conservative argument that if a village was burned, it was the doing of the PKK. In parliamentarians’ reports on excessive force, quoting or mentioning meetings with regional administrators was an observable trend. While this tendency indirectly showed parliamentarians’ lack of trust in official statements that explained village burnings through PKK violence, it also became a discursive tactic, in which liberal parliamentarians defended their arguments against conservative politicians, who adopted the official state discourse. Liberal parliamentarians generally explained the practice of excessive force by pointing to a lack of communication between super-governors and military branches, as well as within the military branch itself. Moreover, such reports of misconduct generally ended with a statement criticizing decision- making bodies for their disregard of these abuses. While parliamentarians in the liberal line argued that village evacuations benefited the PKK in the long run, they also complained about security forces’ lack of accountability.

The security discourse was another multi-partisan discourse, albeit used more by conservative parliamentarians. One type of argument constructed security within the context of parliamentarians’ obligations towards their constituencies, highlighting the state’s responsibility in providing security. Within this parent-type discourse, military and police chiefs were criticized for their lack of awareness and preparedness, and governing coalitions were told to ‘step down’ if they could not provide security. In defense of security- deficit criticisms, governmental discourses, regardless of the political group, focused on the difficulty of combatting the PKK even in violent incidents. To highlight the difficulties in fighting terrorism, security discourses were also generally supported by statistical data, such as villages or hospitals destroyed by the PKK.

4.Discussion

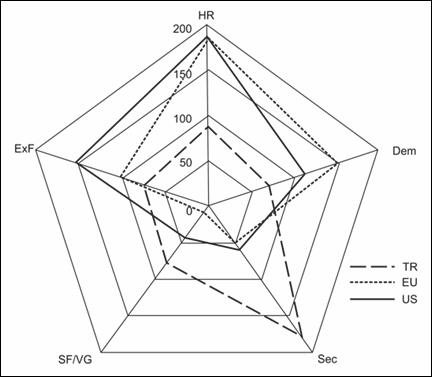

A comparative analysis of the legislative discourses on an intra-state conflict enables us to see the difference in priorities within each setting with regard to that conflict, as well as each legislature’s culture and tradition with regard to intra-state conflict in general. With regard to the Kurdish question in Turkey, we see from Figure 9 how such priorities compare for five of the most frequent themes: HR, Dem, ExF, Sec, and SF-VG.

Figure 9: Radar graph comparing EP, USC, and TGNA aggregate discursive output over five of the most frequently adopted contexts

The HR dimension of the conflict is the primary context of choice within the USC and EP; according to both of these legislatures, the Kurdish question in Turkey was essentially an HR problem, which could be solved by providing special status and rights to Turkey’s Kurdish population. These two legislatures parted ways when it came to their second most frequent discursive context; for the USC, the Kurdish problem had an ExF secondary dimension, whereas for the EP it was secondarily a Dem issue. Predictably, the TGNA had a very different agenda and perception of the issue. There, the Kurdish problem was primarily a Sec problem, which could only be solved by military and security forces, specifically by increasing military presence in the ERs and by increasing pressure on the PKK though cross- border raids and airstrikes. Moreover, although not presented in the radar graph above (since this discourse type is not valid for the USC or EP), the Kurdish problem according to the TGNA was primarily caused by foreign countries (For), instigated and financed deliberately to partition and destroy Turkey. However, rather counterintuitively, the TGNA also emerged as the most frequent critic of security force and village guard abuses (SF-VG) in the south- east. We observe that the EP was quite reluctant to put the blame on Turkish security forces directly, instead implying criticism of security institutions. In this respect, the USC was more confrontational with such institutions, mostly because an overwhelming majority of the materiel used by these institutions was American in origin, the export of which depended upon Congressional consent. This finding also explains the second discursive context of choice in the USC, the ExF dimension. The EP’s second choice of discursive context (Dem) was strongly connected to Turkey’s EU membership process, which is greatly affected by the EU accession (Copenhagen) criteria, requiring the improvement of democratic institutions and practices in a candidate country. It must also be noted that the EP emerged as more sensitive toward Turkey’s right to defend its citizens against the PKK, highlighting the security dimension (Sec) more often than criticizing Turkish security forces (SF-VG). The USC, by contrast, highlighted the security aspect of the conflict but also criticized Turkish security forces and village guards more frequently than the EP did.

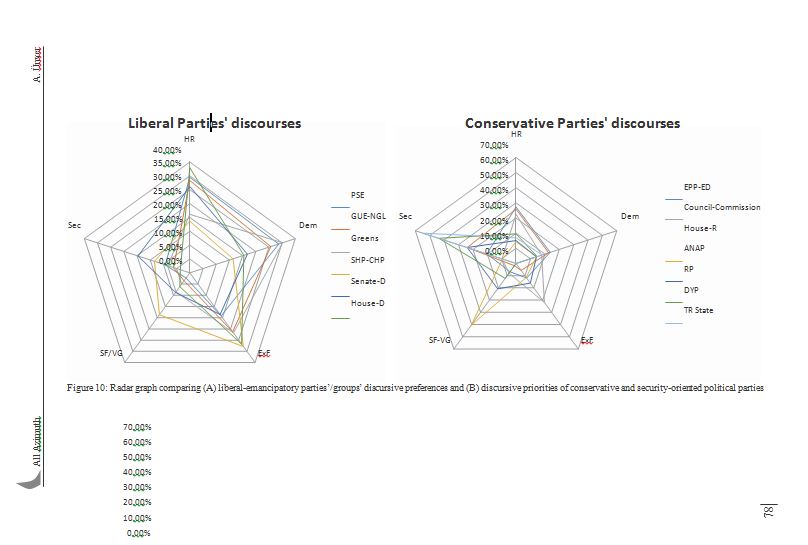

As mentioned earlier, ideology and party affiliation were important factors in legislators’ approaches to the Kurdish question, both in the EP and the TGNA; we also saw that ideology and party affiliation played a very minor role within the USC. A tri-legislatorial comparative analysis of how ideology shaped legislators’ discourses on the Kurdish question reveals the differences of degree between them. Table 17 and Figure 10A show the discursive context used by liberal parties in each legislature as a percentage of their respective aggregate discursive outputs.

Table 17- Discursive preferences of parties/groups taking a liberal-emancipatory position on the Kurdish question

|

HR |

Dem |

ExF |

SF/VG |

Sec |

|

|

PSE |

34.46% |

33.72% |

19.18% |

2.32% |

9.30% |

|

GUE-NGL |

33.33% |

30.70% |

26.31% |

3.50% |

6.14% |

|

Greens |

21.12% |

35.21% |

26.76% |

8.45% |