Efe Tokdemir

Bilkent University

In this paper I investigate terror groups' survival. The fate of terrorists hinges heavily on the power the terror group derives from its reputation. The reputation, which depends on policies and actions the group takes within their constituency, determines the degree to which each group can find recruits, resources, and support for its cause. I contend that terror groups investing on positive or negative reputation within their constituency— the people they claim to represent==are likely to survive longer. Yet, I argue, building a positive reputation has a greater impact on a group’s staying power given that this attracts loyal and committed supporters. Conversely, groups with no clearly defined reputation-building policies undergo an organizational change. I find support for my expectations by testing my arguments over all domestic terror groups active between 1980 and 2011 using the RTG and GTD databases. The findings reveal that once a terrorist group is formed, it is exceedingly difficult to obliterate it so long as it follows a clear reputational strategy to achieve their goals.

1.Introduction

Boko Haram, a fundamentalist terror group in Nigeria, has abducted over 500 schoolboys, seized towns and territories, and killed thousands of civilians since its inception in 2002. Despite being highly unpopular among Muslim Nigerians, the constituency it is claiming to represent, and the efficacy of the Nigerian military and police forces that continue hunting it down, the terror group is yet to be defeated. How does a brutal, unpopular terror group like Boko Haram manage to survive? True, terrorism is a relatively inexpensive tactic and easy to conduct, with many potential benefits such that even groups with meager resources can linger on.[1] Nevertheless, groups who used terror tactics in the past like the Red Brigades in Italy or al Gama’a al-Islamiyya in Egypt have long been defeated. While terrorism, as a tactic, can prolong the survival of non-state actors, this variation in terrorist groups’ survival records poses an interesting puzzle. In this project, I seek to resolve this puzzle.

While state sponsorship of terrorism has dwindled in the aftermath of the Cold War,[2] acquiring internal resources, whether they are about material or non-material sources of supply, continues to matter for non-state actors and even more so in the absence of external patronage. In line with Akcinaroglu and Tokdemir,[3] I argue that groups engaging in the strategy of winning the hearts and minds of their constituencies (positive reputation building) are well equipped to sustain the internal resources required for the survival of the group. This result also applies, however, to groups like Boko Haram that conversely adopt coercive policies (negative reputation building) such as kidnapping, forced recruitment, or extortion, which terrorize their own constituency. Both types of terror groups are able to find money, food, recruits, and safe havens to continue their activities. The key differences, however, are in the way they obtain these resources, voluntary in the former case and coercive in the latter, which affects the relative success of positive versus negative reputation on group survival. Terror groups seeking constituency support achieve not only a high level of internal resources (e.g. many recruits) but also of high-quality resources (e.g. committed recruits). In contrast, groups that use coercive tactics achieve the former but not the latter, which in return reduce the life span of the groups.

Lastly, I argue that groups with neutral reputations are more likely to opt for organizational transformation as, lacking full legitimacy, such groups have the motivation to experiment with change, while the minimum acceptable level of legitimacy they have lowers the risks of change. In sum, I argue that reputation building strategies that help achieve both quantity and quality in internal resources matter in understanding groups’ survival.

The contribution of this article is fourfold: First, by offering an alternative explanation which builds on a non-violent aspect of terrorism studies, I demonstrate that the success of terrorist groups does not merely rely on their military effectiveness. Instead, I argue, it is also the non-violent strategies they engage in that provide them with necessary resources to continue their operations. Second, and relatedly, by focusing on the non-violent aspect of the story, I take terrorist groups as organizations that prioritize their survival. Hence, terrorist groups are not only determined to resort to violence, and to sacrifice themselves to achieve their political goals, but also to survive for post-conflict setting. Thirdly, while my arguments can equally apply to groups using guerilla tactics, my focus in this paper is exclusively on non-state actors using terror tactics. After all, since terrorism is a tactic of the weak, the need to find resources should be more pronounced for such groups, and the impact of reputation building in their constituency is expected to be more vital for their survival. Hence, I go beyond group level indicators of capabilities such as peak size to comprehend group viability.[4] Instead I look at group strategies of reputation building as a signal of the quantity and quality of internal resources vital for survival. Since reputation building is a lengthy process, it works as a credible and costly signal of the group’s short- and long-term potential to survive.[5] I argue that reputation provides a better assessment of the real capabilities of each terror group rather than its current size. Specifically, those groups with high constituency support are the ones most likely to survive. Fourth, as a policy implication based on the findings, I contend that counterterrorism strategies should be geared towards weakening the reputation base of groups that enjoy legitimacy within their constituency by substituting for the group provision of public goods and addressing the roots of grievances through political and economic reforms.

In the next section, I discuss previous work on terrorism to lay out my contribution to the literature. Then, I outline the main argument in the theory section by hypothesizing the relationship between positive/negative reputation in terror groups’ constituency and group survival. In the research design section, I discuss the data and coding, which is followed by the findings in the analysis section. Lastly, I conclude the research by way of discussing the policy implications of the argument.

2. What We Already Know about the Survival of Terror Groups

Group level quantitative studies of terror groups is still a recent development in the literature, and only a few have investigated the survival of terror groups. While Fortna shows that terrorism as a tactic prolongs the survival of non-state actors, her work includes only rebel groups and does not shed light on what influences the longevity of groups among those who use terror tactics.[6] Blomberg, Gaibulloev and Sandler argue that both ideology and tactics matter in terror groups’ survival. [7] Specifically, they show that religious and capable groups, and those using diversified tactics, are more likely to be durable. Young and Dugan on the other hand examine the environment in which terror groups operate.[8] By applying the theory of outbidding, they argue that strategic competition between groups leads to group failure where only old dogs, those with greater resources, can manage to survive. In contrast, Phillips demonstrates the role of cooperation between terrorist groups as having a positive impact on their survival.[9] Blomberg et al. find that older transnational groups and those that are lethal are more likely to survive.[10] Abrahms argues that branding is crucial in the success of terrorist groups, hence avoiding brutal attacks.[11] Lastly, Daxecker and Hess turn to government strategies to explain the duration of terror groups, basically arguing that repression helps thems survive by creating a backlash against measures taken by governments.[12]

While I agree with the above scholars that capabilities, ideology, competition, age, lethality and resources are relevant indicators of group duration, I take a step backward and focus on group strategies of reputation building to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of why and when these indicators may matter. For example, terror groups with a positive reputation are more likely to find recruits willing to fight for them. However, while recruitment is voluntary in groups with positive reputations, groups with negative reputations are equally successful in increasing their groups’ size by forced methods. The difference between the two types of groups, however, lies in their future viability and the level of commitment of their recruited members. While the first group can benefit from a continuous stream of committed recruits, the second group’s viability is endangered by the limits of forced recruitment.[13] Another robust finding in the literature is the relationship between a group’s religious ideology and its survival. However, those findings fail to take into consideration other factor, for example, many religious groups such as Hamas, Taliban, and Hezbollah have built a positive reputation in their constituency by investing in healthcare, schools and charities which may explain why these groups may be durable.[14] Young and Dugan argue that competition and greater resources overall decrease the life span of groups.[15] Along the same lines, Nemeth argues that groups become more lethal in competitive environments in an effort to outbid others.[16] Related to this, I argue that reputation building is a crucial mechanism through which groups acquire resources for lethality and distinguish themselves from rival groups in competitive environments. Those that can do this based on their good reputation can survive in a competitive environment while forcing others’ demise. Thus, exploring group strategies of reputation building is in the right direction; the reputation of groups provides a comprehensive theory that merges most of the current findings from the literature, offering refined conditions under which those indicators are most effective, as well as suggesting other novel means to understand the survival of terror groups.

3. Reputation and Survival

A terror group, like any other non-state actor, requires resources to purchase weapons and food, take care of day-to-day expenses, travel, train, and fight. The viability of a terror group heavily relies on the extent to which the group can acquire these tangible and intangible assets. Terror groups can either find these resources externally and/or internally. States have often sponsored terrorism in the past to topple hostile regimes,[17] but this trend has declined with the end of the Cold War. Of the 36 groups on the U.S. foreign terrorist organizations list in 2002, less than a quarter enjoy state support today. Hence, the importance of safeguarding internal resources has become of paramount importance to terror groups. How can terror groups generate these internal resources? At this point, Mao Tse-tung’s wise quote comes to mind: “The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea.”[18] Like any other non-state actor, terror groups heavily rely on their constituency, the group of aggrieved people they claim to represent and fight for, to provide them with most of the resources.

Terror groups can differentiate themselves from others if they win the hearts and minds of their constituents, that is, by building a positive reputation.[19] The process of building reputation is not costfree, but by spending meager resources on the welfare of their constituency, terror groups can send a costly signal about their commitment to the people they fight for. One way to win the support of the people is through the provision of public goods such as education, health, or law and order. Substituting for inadequate goods and services binds constituents to the group in a web of loyalty and affection. According to Chandrakanthan, provision of services by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) increased the loyalty of the Tamil youth to the group, created community support, and minimized the need for the LTTE to resort to coercion.[20] Hezbollah spends millions of dollars on its Shia constituency; and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) established gender equality laws, adopted land reform, built infrastructure, and delivered social services in the areas it liberated, despite its scarce resources.[21] By investing time and resources in the welfare of its constituents, both of the latter groups gathered thousands of voluntary recruits that helped them survive for decades against the powerful Israeli and Ethiopian armies respectively.

Using mass media, terrorist organizations can publicize the past and current grievances of the people, use myths and symbols to cement existing identities, and enhance the group’s image by focusing on victories and reframing losses. A terror group can broadcast terrorist propaganda on TV, through the internet or in printed form, to inspire the masses by disseminating the heroic deeds of the fallen and the unwavering courage of those still standing.[22] Terror groups can also form political wings or political parties to help consolidate grassroots support. Political branches can reach out to local people, spread the group’s ideology and improve upon the negative connotation attached to its activities by highlighting the group’s political aspirations. Thus, the provision of public goods, mass media advertisement, and engagement in politics all help to provide legitimacy to terror groups and bring much needed constituency support. The sympathy of the constituency in return helps groups remain active by allowing them to find a pool of available recruits to replenish or increase their membership to survive.[23]

Like any other investment, positive reputation building brings not only short term but also long term benefits. People who believe in the terror group and fight for its cause are likely to pass that ideological commitment and conviction on to their close friends and relatives, and their children tomorrow. The members of the IRA, for example, belonged to the same families over multiple generations.[24] The means through which terror groups build a positive image, that is establishing a political branch or party and using mass media channels, make it easier to justify the group’s ideology to those people whose motivational process has already been set in motion by their closeness to existing recruits.[25] In sum, while I acknowledge that positive reputation building requires resources, even small amounts of resources spent on constituents bring short and long term benefits that go well and beyond the groups’ initial investment, thereby increasing the group’s viability. Thus, I pose the following hypothesis,

Hypothesis 1: Groups with high positive constituency reputation are more likely to survive compared to other groups.

Not all terror groups choose, however, to invest in strategies that build a positive reputation. Production and distribution of goods and services, establishment of a political wing, and foundation of a press require effort and time, even if such strategies do generate ample internal resources. Alternatively, a terrorist organization may employ coercive tactics (e.g. build a negative reputation) to bring in the required resources in the short run. Kidnapping civilians for ransom, abducting children or adults for recruitment, or extortion, all create internal resources vital for the group’s militant survival. For example, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) founded in 1991 in Sierra Leone has employed cruel tactics to consolidate its power. It has recruited thousands of children and men forcefully, trained them to attack villages, loot, and set up roadblocks for the purpose of extortion.[26] Similarly, Boko Haram has acquired millions of dollars from kidnapping, drug trafficking, and bank robbery, and has forcedly recruited children into its ranks. These cases demonstrate that despite alienating their constituencies, groups with negative reputations can also manage to accumulate internal resources via coercive policies. Thus, I posit my second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Groups with high negative constituency reputation are more likely to survive compared to other groups.

So far, I have argued for the advantages of good, and disadvantages of bad, constituency reputation for terror groups. But what happens to groups that are unable to distinguish themselves either through good or bad constituency reputation —those groups that meander on an uncertain course? Or, what can these groups do to survive despite the lack of means to build good constituency reputation, or the means to avoid all the policies that build a negative group image? I argue that groups with a neutral image—those with neither completely good nor bad reputation— tend to terminate their operations given that they have neither carrots nor sticks in their arsenal to acquire necessary resource to maintain their operations.

Hypothesis 3: Terror groups with no investment on constituency reputation are more likely to go for organizational change than groups with good or bad constituency reputation.

Despite the acquisition of a high amount of internal resources, groups with negative reputation suffer from the quality of resources. Coercive policies create an abundant flow of recruits who stay either because of self-enrichment or flee at the first glimmer of opportunity. The use of threat in recruitment brings a constant need for policing to prevent defection, which in the long run becomes a costly investment for the group.[27] Terrorists rewarded for abducting kids and young men, forcing civilians to provide food, money or safe haven, learn to act without limits, often resorting to excessive and pointless violence, looting, and other types of crimes against the constituency they claim to represent. Having limited constituency support, the group leadership, in return, faces no incentives to discipline its members or punish them for their behavior towards their constituency.[28] Shortly, the absence of constituency support sets off a vicious cycle by making group members more reckless in behavior, which further diminishes the group’s support, and induces incentives to defect to the government side.[29] In sum, groups with negative reputation can find the resources for group survival in the short run, but the low quality of recruits and the limits of coercive policies endanger the group’s viability in the long run. Thus, I argue the following:

Hypothesis 4: The impact of high negative reputation on group success is likely to be lower than the impact of high positive reputation on group success.

4. Research Design

The data are in group-year format and include 443 domestic terrorist organizations operating over a span of 31 years and listed in the Reputation of Terror Groups (RTG) dataset.[30] The dataset is limited to groups with at least five attacks in the time period between 1980 and 2011, resulting in a total of 2,645 observations listed. By restricting the sample to domestic groups with at least five attacks, I aim to prevent any bias in the empirical analyses such as lack of a clear constituency or of intention to build reputation.

4.1. Dependent variable

For Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, the dependent variable is the survival of a terrorist group, and the length of survival refers to its age in each year. On average, terror groups survive for 15 years. I right censor observations that are still ongoing by 2011. For Hypothesis 4, I updated and recoded the variable, “ended” in RAND’s ‘How Terrorist Groups End’ database.[31] The ended variable is coded in six categories: defeat, policing, victory, politics, splintering and merge. Among these categories, I coded Success as the dependent variable if the terror groups ended their operations by acquiring a victory through military means by toppling the incumbent government or declaring independence or autonomy, or engaging in political space as a result of a concession by the incumbent. Out of the 443 terror groups in the dataset, 37% achieved success, 43% failed through military defeat or policing, and 20% underwent organizational change (merging with others or splintering).

4.2. Independent variables

I use three independent variables to test the hypotheses: positive reputation (Hypotheses 1 and 4), negative reputation (Hypotheses 2 and 4), and no reputation (Hypothesis 3). To form these variables, I utilize six variables coded in the RTG dataset. The dataset first identifies the constituents of each group, and then codes three positive and three negative actions, which I combine and label as positive and negative reputation, respectively.[32] The positive reputation variable is an additive index composed of public goods provision, media power, and political existence. Groups that provide public goods such as free education, security, or health services to their constituency can enhance their image. Second, terror groups that own a television or radio channel have the means to disseminate their grievances and spread their propaganda, thereby affecting the way their constituency perceives them. And last, terror groups affiliated with a political party, or those with a political branch can also increase their support at the grassroots level by spreading their political ideology and message. By adding the scores of each group on these three indicators, I arrive at a 0-3 scale that represents the internal-constituency reputation of each group.

The negative reputation variable is also an additive index composed of forced recruitment, child recruitment, and forced funding. Coercive strategies tend to be highly unpopular, with terror groups that do resort to abduction or forced funding generally alienating their support base. Adding these up, I created an ordinal variable ranging from 0 to 3. And lastly, I created a no reputation variable by coding terror groups as 1 if they did not engage in substantive reputation building strategies (scoring 2 or 3 in either reputation dimensions), and hence score 0 or 1 in both positive and negative reputation dimensions. Scoring 0 and 1, in that sense, means a group was either not investing on reputation strategies at all, or only had limited investment on selected cheap strategies, which could have limited impact on the constituents, if any at all. The variable coded 0, if the group scored 2 or 3 in any of these dimensions.

4.3. Control variables

At the group level, I controlled for whether the terrorist organization is a rebel organization or not by referring to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Dyadic Dataset, as rebel groups that oscillate between guerilla and terror tactics may have more constituency support.[33] I also controlled for goals of terror groups, as groups with broader objectives are less likely to have constituency support.[34] I updated the Type and Goal variable in Jones and Libicki’s data and I recoded the variable goal in a binary nature, with 1 indicating broad objectives (social revolution and empire) and 0 indicating relatively limited objectives (policy change, territorial change, regime change, and status quo). I controlled for ideology, as religious or ethno-nationalist groups are less likely to perish.[35] The term International codes terror groups operating cross-border, as groups with multiple bases may have more internal resources.[36] Since competition may hasten each group’s demise, I also control for the number of terror groups operating simultaneously.[37]

The findings in the terrorism literature show that contextual factors are effective in shaping terrorist groups’ strategies. For example, Blomberg et al. show that democratic institutions enhance the survival of terror groups. [38] Higher socioeconomic conditions may indicate a larger state capacity, increasing the chances of achieving outcomes that are worse than the status quo for each group.[39] In contrast, extensive surface areas create monitoring problems for the state thereby facilitating the survival of terror groups,[40] while large supplies of discontented youth generate opportunities for group recruitment[41] thereby increasing the chances of survival of each group. Thus, I added national level control variables such as the polity score from Polity IV, logarithmic area from Piazza, and the logged GDP per capita of the country each terror group operates in.[42] Additionally, I controlled for the post-Cold War era, as state sponsorship for terror groups has shrunk with the end of the Cold War, thereby hastening the defeat of terror groups.

4.4. Model specification

To test Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, I employ a Cox proportional hazards model and estimate the impact of each terror group’s reputation on the survival of each group. The basic specification for the Cox model is:

hi(t) = h0(t) exp(β1xi1 + β2xik + ・ ・ ・ + βkxik) or h(t)=h0(t)exβ

where h0(t) is the baseline hazard, β’s are slope parameters, and x’s are independent variables. In this semi-parametric model, the hazard function, h0(t), remains unspecified while the covariates enter the model linearly. I report the hazard ratios which are interpreted according to whether or not they exceed 1; those ratios that are greater than 1 imply that greater values of the variable increase the risk of failure, or in this case, the termination of conflict with each terror group. Higher values of the variables with hazard ratios less than 1 contribute to the survival of the terror group or continuation of terrorism.

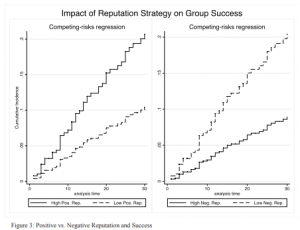

To test Hypothesis 4, I employ a competing-risk model, as standard survival analysis takes failure-time with a single type of failure into account. A failure, in this case, the termination of the conflict with each terror group, may occur due to different events that are independent from each other.[43] In the data, I have several competing events for the termination of conflict: the terrorist group achieving victory, engaging in politics, being defeated militarily, being criminalized by local law enforcement, or undergoing an organizational change (splintering or merging). Occurrence of any of these events competes to determine the termination of conflict for each terror group. If the event of interest is success, as in this case, then the term competing risks refers to the chance that instead of success, I will observe other events that terminate conflict, such as failure or organizational change. When competing events exist, hazards are computed for the event of interest as well as for competing events, h1t, h2t, h3t, h4t where the cumulative incidence function (CIF) the probability that the event of interest occurs before t, will depend on the hazard of the main event as well as the hazards of competing events.[44]

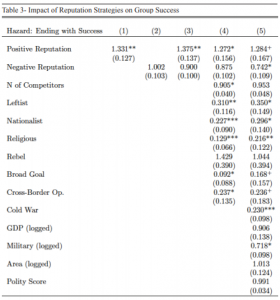

5. Results

I present the results of the empirical analyses by reporting the hazard ratios in Tables 2 and 3. Hazard rations represent the likelihood of facing the hazard, in this case, termination of a terrorist group’s operations. If the ratio is higher than one, it means observing the hazard is more likely, and if smaller than 1, then observing the hazard is less likely. I first performed diagnostics checks to test the assumption of proportionality of hazards. Aside from using the phtest command of Stata, which automatically detects any violation of proportional hazard assumption, I also plotted Schoenfeld residuals to see possible violations manually.[45] Then, I re-estimated the analysis in the model by applying time varying covariates for the variables that failed the individual and global test.

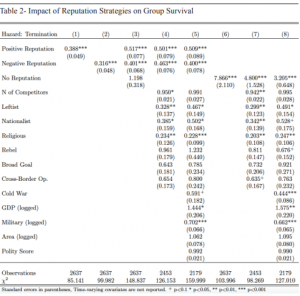

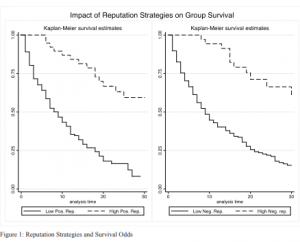

The results confirm the first hypothesis on the survival of groups, that is, groups that have obtained legitimacy by investing in positive reputation are more likely to survive. I find that one-point increment change in positive reputation (ranges between 0 and 3) decreases conflict termination by 50% based on the full models. This is expected as constituency support provides the groups with the necessary resources and committed recruits to ensure their viability. In Figure 1 (left), I plot the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of the groups with high and low positive reputation scores. At the mean analysis time (15 years), survival probability of a group with very low positive reputation is 32% whereas it is 80% for groups with high positive reputation (reputation score=3) ceteris paribus.

Models in Table 3 also reveal that terror groups that invest in negative reputation are also more likely to survive. One-point increment in negative reputation (ranges between 0 and 3) decreases conflict termination by 60% based on the full model (Model 5). Negative reputation may not provide those groups with constituency support in the long run; but investing in negative reputation may help groups find resources and recruits in an inexpensive way, which eventually increases the capabilities of the group in the short run. Indeed, substantive analysis drawn in Figure 1 (right) shows us the effect of negative reputation: at the mean analysis time, the probability of survival is only 38% for groups with very low negative reputation while it is 78% for groups that have invested in high negative reputation.

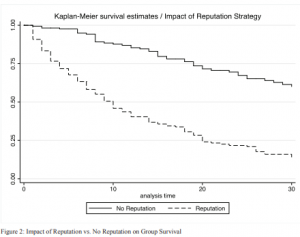

Lastly, in line with Hypothesis 3, which is partly tested in the previous analysis, I find that groups not investing on reputation strategies are dramatically less likely to survive. Looking at Models 6-8 and Figure 2, I see that it is significantly more likely for terrorist organizations that invest heavily on either positive or negative reputation to survive. Contrary to this, those groups not investing on constructive or coercive strategies fail to survive as a result of lacking enough supplies to maintain their operations.

Most of the other control variables are in the expected direction: the Post-Cold war era has diminished available external resources hastening the termination of terror groups. I also find that groups that switch between guerilla and terror tactics (rebel terrorists) and those that operate cross nationally are more durable. However, I also have some unexpected findings, for example larger military size seems to be prolonging group survival while large surface area seems to be shortening it. It may be that states with strong militaries may be tempted to resort to military tactics to defeat terror groups, an ineffective counter-terrorism strategy as suggested. Larger surface areas may also lead to the emergence of multiple groups, a factor that may bring competition and group defeat.

These results also reveal the importance of reputation building in general regardless of the type of reputation. While positive reputation increases the survival of terror groups, negative reputation also serves this purpose, as expected, through resource extraction. This implies that not adopting a reputation building strategy is suicidal for terror groups. I do not imply that the inability to build any type of reputation is a deliberate strategy. Instead, I contend that if a terror group can build neither positive relations with its constituency nor manage to extract resources forcefully, then it is very plausible for that group to quickly terminate.

In Table 3, the main independent variables are once again positive and negative reputation. Yet, this time I do not analyze whether a group with specific strategy can survive, but rather the likelihood of achieving success in its operations. The findings confirm that terror groups with positive reputations are more likely to achieve success. One-unit increment in positive reputation score increases the probability of a success by 27%. I plot the cumulative incidences in Figure 3 (left). At the mean age of terror groups, those with higher positive reputation are almost four times more likely to end up in victory or politics. Lastly, I applied some diagnostic tests for models; I analyzed the residuals, which are estimated as a function of exponential time. If proportional assumptions hold, these residuals should be a random walk unrelated to survival time. Using Schoenfeld and scaled Schoenfeld residualsI tested the proportionality assumption in all three models, but I did not detect a violation of the assumption in any of the variables. [46]

6. Conclusion

Terrorism is a tactic that helps non-state actors survive, but what explains why some groups that use terror tactics tend to survive longer than others? Terror groups need resources to survive, but the end of the Cold War has decreased state sponsorship for terror groups, making it more vital for them to sustain internal resources. In this paper, I argue that reputation building strategies are good indicators of the extent to which terror groups can acquire internal resources, both in terms of quantity and quality.

The findings reveal that either playing the good or bad guy can actually extend the survival time of terrorist groups, as they are more likely to acquire their needs voluntarily or forcedfully. To remind, surviving for longer periods neither means the defeat of the government, nor indicates the success of terrorist organizations. Yet, it is a clear indication of an ongoing conflict, and continuation of problems relatedly. Lastly, I showed that to achieve success terror groups should invest in positive reputation building tactics.

Looking at the reputation of the group provides several advantages, the first being that while building a positive reputation is a costly investment, it tends to stick. Thus, reputation provides a costly signal about the type of the terror group, helping policymakers decide whether they are facing a committed and politically driven group with effective governance capabilities, or instead a self-interested and aimless terrorist group detached from the welfare of the people it claims to represent. Good reputation, as a costly gesture, connects the group with the people, helping buy their long-term commitment and loyalty, both of which can help the terror group bounce back even at bad times.

The findings of the article offer important policy implications, as well. The results demonstrate that the existing trends in counter-terrorism strategies to defeat a terror group, without addressing the roots of the conflict or winning the hearts and minds of the group’s targeted constituency, is no longer a viable option. That said, a strategy to follow for an effective counterterrorism is to support weak or failing governments where terrorism might flourish economically to address the grievances of the people before they emerge. Indeed, the United States’ increase in its aid and development programs in building Iraq and Afghanistan can be interpreted along those lines. Moreover, some studies show that the provision of public goods by terror groups that substitute for the absence of government services makes them more lethal.[47] I agree that making governments more effective to drain the swamp can sever the ties between the terror group and its constituency. However, the findings also point to the sensitivity of timing in the adoption of such strategies. Once reputation is built, and the loyalty of the constituents is cemented, then severing the ties may no longer be feasible. Hence, preventive measures should be at the core of counter-terrorism strategies; the findings confirm that political and economic reforms enacted before the reputation of the group sets in will be more effective in weakening terrorist groups.

Abrahms, Max. Rules for Rebels: The Science of Victory in Militant History. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Akcinaroglu, Seden, and Efe Tokdemir. “To Instill Fear or Love: Terrorist Groups and the Strategy of Building Reputation.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 35, no. 4 (2018): 355–77.

Berman, Eli. “Hamas, Taliban and the Jewish Underground: An Economist’s View of Radical Religious Militias.” Working Paper 10004, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004.

Berman, Eli, and David D. Laitin. “Religion, Terrorism and Public Goods: Testing the Club Model.” Journal of Public Economics 92, no. 10-11 (2008): 1942–967.

Blomberg, S. Brock, Rozlyn C. Engel, and Reid Sawyer. “On the Duration and Sustainability of Transnational Terrorist Organisations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54, no. 2 (2010): 303–30.

Blomberg, S. Brock, Khusrav Gaibulloev, and Todd Sandler. “Terrorist Group Survival: Ideology, Tactics, and Base of Operations.” Public Choice 149, no. 3/4 (2011): 441–63.

Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M., and Bradford S. Jones. Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Byman, Daniel. Deadly Connections: States that Sponsor Terrorism. Cambridge

University Press, 2005.

Chandrakanthan, A. J. V. “Eelam Tamil Nationalism: An Inside View.” In Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, edited by A. Jayaratnam Wilson, 157–75. London: Hurst and Company, 2000.

Connell, Dan. “Inside the EPLF: The Origins of the ‘People’s Party’ & its Role in the Liberation of Eritrea.” Review of African Political Economy 28, no. 89 (2001): 345–64.

Conrad, Justin. “Interstate Rivalry and Terrorism. An Un-probed Link.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55, no. 4 (2011): 529–55.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Daxecker, Ursula E., and Michael L. Hess. “Repression Hurts Coercive Government Responses and the Demise of Terrorist Campaigns.” British Journal of Political Science 43, no. 3 (2013): 559–77.

Denov, Myrian. Child Soldiers: Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Dugan, Lauran, and Joseph Young. “Allow Extremist Participation in the Policymaking Process.” In Contemporary Issues in Criminal Justice Policy, edited by Natasha Frost, Joshua Freilich, and Todd R. Clear, 159–69. Wadsworth, 2010.

Eck, Krsitine. “Coercion in Rebel Recruitment.”Security Studies 23 (2014): 364–98.

Ehrlich, Paul R., and Jiangou Liu. “Some Roots of Terrorism.” Population and Environment 24, no. 20 (2002): 183–92.

Enders, Walter, and Todd Sandler. “Transnational Tterrorism in the Post–Cold War Era.” International Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (1999): 145–67.

Eyerman, Joe. “Terrorism and Democratic States: Soft Targets or Accessible Systems.” International Interactions 24 (1998): 151–70.

Farrall, Leah. “How al Qaeda Works: What the Organization’s Subsidiaries Say about Its Strength.” Foreign Affairs 90 (2011): 128.

Fearon, James D., and Laitin, David D. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (2003): 75–90.

Fine, Jason, and Robert Gray. “A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 94 (1999): 496–509.

Fortna, Page. “Do Terrorists Win? Rebels' Use of Terrorism and Civil War Outcomes: 1989-2009.” International Organization 69, no. 3 (2015): 519–56.

Gates, Scott. “Recruitment and Allegiance: Microfoundations of Rebellion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46, no. 1 (2002): 111–30.

Grambsch, Patricia M., and Terry M. Therneau. “Proportional Hazards Tests and Diagnostics Based on Weighted Residuals.” Biometrika 81, no. 3 (2002): 515–26.

Jones, Seth G., and Martin C. Libicki. How Terrorist Groups End: Lessons for Countering Al Qa'ida. Rand Corporation, 2008.

Klein, John P. “Competing Risks.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2, no. 3 (2010): 333–39.

Kruglanski, Arie W., Keren Sharvit, and Shira Fishman. “Workings of the Terrorist Mind Its Individual, Group and Organizational Psychologies.” In Intergroup Conflicts and Their Resolution: A Social Psychological Perspective, edited by Daniel Bar-Tal, 195–217. New York: Psychology Press, 2010.

McLauchlin, Theodore, and Wendy Pearlman. “Out-Group Conflict, In-Group Unity? Exploring the Effect of Repression on Intra-Movement Cooperation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 56, no. 1 (2012): 41–66.

Nemeth, Stephen. “The Effect of Competition on Terrorist Group Operations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 2 (2014): 336–62.

Paul, Christopher. “How do Terrorists Generate Maintain Support?” In Social Science for Counterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together, edited by Paul K. Davis and Kim Craigin, 113–50. RAND National Defense Research Institute, 2009.

Phillips, Brian J. “Terrorist Group Cooperation and Longevity.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 2 (2014): 336–47.

Piazza, James A. “Poverty, Minority Economic Discrimination, and Domestic Terrorism.” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 3 (2011): 339–53.

San-Akca, Belgin. States in Disguise: Causes of State Support for Rebel Groups. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Schoenfeld, David. “Partial Residuals for the Proportional Hazard Regression Model.” Biometrica 69, no. 1 (1982): 239–41.

Tarrow, Sidney. Power in Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Tokdemir, Efe, and Seden Akcinaroglu. “Reputation of Terror Groups Dataset: Measuring Popularity of Terror Groups.” Journal of Peace Research 53, no. 2 (2016): 268–77.

Tse-tung, Mao. On Guerrilla Warfare. Translated by Samuel B. Griffith II. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000 [1937].

Young, Joseph K., and Laura Dugan. “Survival of the Fittest: Why Terrorist Groups Endure.” Perspectives on Terrorism 8, no. 2 (2014): 1–23.

Weinberg, Leonard. The End of Terrorism? New York, NY: Routledge, 2012.

Weinstein, Jeremy. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2007.