Ismail Numan Telci

Sakarya University Middle East Institute

Mehmet Rakipoğlu

Sakarya University Middle East Institute

Strategic hedging has not been studied adequately in Middle Eastern countries. This study is an attempt to include hedging into the analysis of a small state’s foreign policy choices. It contends that the hedging strategy can be applied to small states because it allows them to confront/respond to risks/threats at three levels: international, regional and sub-regional. It is argued that Kuwait has pursued a hedging policy by taking possible shifts in the global and regional power distribution and the lasting regional security dilemma into consideration. By strengthening military cooperation with China and Turkey, Kuwait has aimed to hedge the risks that could arise from the rise of China and Turkey in the Gulf, the US’ retrenchment from the Middle East, and Saudi Arabia’s aggressiveness. The main purpose of this strategy is analysed as a move to empower the regional alliance with Turkey, ensuring Kuwait’s security and warding off potential risks from the changing dynamics of the Middle East.

1.Introduction

Any attempt to conduct an analysis of a state’s foreign policy choices must be divided into categories defining the state’s attributes, such as its size, strength, and capabilities. Within the scope of power, states are generally classified either as a superpower, a great power, or a small power. Due to its limited potential to change the current international order and inability to protect its national interests using its own political or military means, Kuwait is considered a small state. Small states lack the capacity to ensure their own security and are unable to significantly influence international order.[1] Therefore, small powers’ foreign policies generally consist of balancing or bandwagoning. However, there is a smart choice of strategy available to small states: hedging. Hedging allows small states such as Kuwait to offset and reduce the scale of threats. In implementing this strategy, Kuwait can avoid confrontations with the US, China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. While Kuwait’s foreign policy has been widely described as well-hedged, especially regarding its relations with Iraq[2] and Iran[3], there is a significant gap in the literature in terms of analysing Kuwait’s relations with China and Turkey. This study thus aims to fill that gap.

On the other hand, the hedging strategy has been studied by focusing on threats. In this sense, Kuwait’s hedging is considered a tactic used to address Iranian expansion, Iraqi irredentism, and the domestic uprising of Shiites. While we agree with this analysis, we contend that hedging is not only a strategy to be used against threats. Rather, we argue that hedging can also be used for the benefit of rising powers. With the Kuwaiti example in mind, hedging is implemented in order to manage potential risks and additional costs from China and Turkey’s growing influence in Gulf politics.

Lastly, hedging is generally employed in order to avoid threats from rising regional powers. In this sense, Kuwait seeks to avoid confrontations with China and Turkey. Additionally, by hedging, Kuwait is not beholden to China or Turkey. In other words, Kuwait’s security environment is not based on the rigid logic of an alliance bloc. Kuwait need not sever its ties with the US or Saudi Arabia despite China’s and Turkey’s interest in the area. As an alternative strategy for Kuwait, hedging allows it to maintain good relations with all powers. Rather than prioritizing relations with either the US, China, Saudi Arabia, or Turkey, we argue that by improving ties with China and Turkey, Kuwait hedges them and maintains multiple policy options. To reflect this, we selected the types of hedging that were developed by Koga.[4]

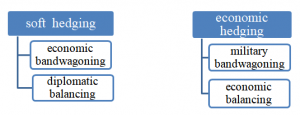

Based on Koga’s methodological framework, it can be argued that engaging in economic bandwagoning and diplomatic balancing constitutes soft hedging, which is Kuwait’s strategy towards China. On the other hand, Kuwait’s strategy towards Turkey can be defined as economic hedging, which includes military bandwagoning and economic balancing.

In order to understand the dynamics, instruments, and motivations of Kuwaiti foreign policy, the study firstly reflects on the foreign policy objectives and choices of Kuwait at a historical level. Given the recent shifts in the global power structure, Kuwait has also been in search of a change, albeit a limited one, in its foreign policy direction and priorities. It is important to understand these changes in order to better evaluate whether Kuwait is attempting to implement a new foreign policy direction, different from its traditional one.[5]

The study employs a relatively new and, to some extent, novel approach by classifying Kuwaiti foreign policy behavior as hedging rather than bandwagoning or balancing. It is, therefore, the aim of this study to assess whether Kuwait pursues a hedging strategy in its foreign policy. In order to better analyse the topic and test the assumptions, the study focuses on Kuwait’s foreign policy choices towards China and Turkey. By understanding the strategic choices Kuwait made in relation to these countries, the study reveals why and how bandwagoning and balancing are no longer rational policy choices for Kuwait. As the study unfolds, hedging is offered as the most suitable foreign policy strategy for Kuwait. The initial phases of this study focus on the theroretical account of the hedging strategy, which also discusses the security dynamics within the Gulf region. Extracting from the literature on hedging, this part is devoted to defining hedging as well as Kuwait’s choice in strategy. The succeeding sections detail Kuwait’s policies towards Turkey and China while documenting Kuwait’s growing rapprochement with both countries.

2. Hedging as a Foreign Policy Strategy

Hedging strategy is derived from economics.[6] In the 1940s, economists proposed and refined the concept of hedging. Hedging theory had become a staple in finance by the 1960s. While the concept began to appear in the works of IR scholars in the 2000s[7], strategic analysts and policy makers are also increasingly subscribing to the concept of hedging, with most applications reflecting US policy perspectives. However, hedging in international politics has never been clearly defined. Without a common definition, hedging appears as an underdeveloped concept. [8] Therefore, even if there exists a plethora of studies on hedging, there is a lack of consensus on its definitions, motivations, conditions, patterns, and identification.[9] The nature of hedging has thus not been fully explored.

Hedging can be defined as the position of states that aim to offset potential losses or gains. It helps a small state to prepare for confrontation, uncertainty, and risks by protecting and promoting its security position in case its relationship with the leader of the unipolar system worsens. It is a useful strategy for states that are unable to settle on other strategies such as balancing, bandwagoning, or buck-passing. Evelyn Goh, for instance, defines hedging as “a set of strategies aimed at avoiding (or planning for contingencies in) a situation in which states cannot decide upon more straightforward alternatives such as balancing, bandwagoning, or neutrality.” States seek to “cultivate a middle position that forestalls or avoids having to choose one side at the obvious expense of another.”[10] Roy defined hedging as “keeping open more than one strategic option against the possibility of a future security threat”.[11] His definition does not question whether the state has decided to take sides, nor the degree to which the state has weighed one strategy against another when it mixes strategies. Because Roy’s definition mixes balancing, bandwagoning, neutrality, engagement, and accomodation, there can be difficulty in identifying and implementing it in a specific case. A more detailed definition, by Cheng-Chwee Kuik, defines hedging as “a behavior in which a country seeks to offset risks by pursuing multiple policy options that are intended to produce mutually counteracting effects under the situation of high-uncertainties and high-stakes”.[12] Kuik’s definition of hedging offers by far the most precision and allows us to think about policy application. Its aim is clear: “offsetting the risk”. By aiming to offset the potential risk of choosing one state over another, the hedging state avoids provoking the target states. David Lake, meanwhile, defines[13] hedging as “an insurance policy against opportunism” while Medeiros defines it as a “geopolitical insurance strategy” because it allows states to offset and reduce the scale of potential threats in their relations with both international and regional powers without confronting any of them.[14] Similarly, Tessman and Wolfe define strategic hedging as an insurance policy that helps states guard against two possibilities: that relations between the hedging state and the system leader deteriorate to the point of a militarized crisis, and/or that the system leader will cease the provision of public goods that the hedging state currently enjoys.[15] However, by defining hedging as merely a response to the “system leader” by second-tier states[16] in a unipolar system, Tessman and Wolfe’s theoretical exposition of hedging is too restrictive and narrow, hence missing a wide range of hedging behaviors under other conditions. Containment is not hedging, just as using force is not deterrence. Use of force is an option after deterrence fails. Similarly, containment is an option should hedging fail. Such a distinction is helpful for theoretical rigor as well as more rigorous strategic and policy analysis. This strategy allows states to utilize other instruments of statecraft, such as enmeshment, balancing, engagement, and restraining.[17]

Hedging is a strategy that can be employed by any kind of state.[18] It is argued that hedging is generally used by second-tier states as a strategic option, but it can also be used by great powers.[19] There is a plethora of studies on hedging[20] being employed as a strategy focused mainly on the Asia-Pacific region[21]. China’s utilization of hedging as a strategic option in its competition with the United States is widely studied in scholarly literature. We also contend that hedging is ideal for exploring the behaviors of small powers, such as those of Kuwait, [22] which we argue has received relatively little attention, especially regarding its relationships with China and Turkey.

The final theoretical consideration here is that hedging is irreducible to a single country, issue, or region. Instead, as we argue, hedging can occur at multiple levels and issue areas, and can therefore be best understood through the lens of a level-of-analysis. In other words, Kuwait hedged China and Turkey at the international, regional and sub-regional levels.

We argue that Kuwait can hedge not only in the center of the Middle Eastern multipolar system, but also with other regional and global powers. This hedging strategy can be studied through an investigation of regional and sub-regional dynamics, such as the Arab uprisings, the uncertainty about US intentions, the rise of new actors in Gulf politics, and other geopolitical risks. The argument is that, considering the possible shifts in the global and regional power distribution and lasting regional security dilemma, Kuwait preferred to hedge rather than employ balancing or bandwagoning. Kuwait intends to strengthen its military alliance with China while seeking to develop a stronger partnership with the US. On the other hand, it also wishes to strengthen its military alliance with Turkey, simultaneously hoping to develop a stronger partnership with Saudi Arabia. Therefore, Kuwait’s hedging strategy has at least two logics: pursuing defensive strategies to ensure its security and empowering its regional alliance with Turkey to ward off potential risks emanating from the changing dynamics of the Middle East.

The first logic is mostly a consequence of the regional policies of the United States, which have resembled a swinging pendulum in recent years. As explored in later sections, Washington’s ambivalent policies about intervention have created uncertainties and risks for regional powers by creating a power vacuum that has potential to be filled by threatening actors such as Iran, Hezbollah or ISIS. Meanwhile, as showcased in the past decade by regional powers like Egypt, Libya, Yemen, countries of the Horn of Africa, and the Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have adopted more aggressive and assertive foreign policies. To deal with the risks and uncertainties of the US’ and Saudi Arabia’s policies, Kuwait again approached China and Turkey respectively. While getting closer with Beijing and Ankara, Kuwait also felt compelled to keep its favourable relationship with both Washington and Riyadh. Clearly, Kuwait uses neither balancing nor bandwagoning in its strategy regarding these four states; rather, it hedges.

3. Hedging As Foreign Policy Strategy for Small-States: A Conceptual Approach

According to structural realism, the polarity of the international system (unipolar, bipolar, multipolar), shapes the behavior of states to a great extent. In a unipolar international system, “small” states can rely on several strategies to survive. The anarchical nature of the international system forces small states to implement hedging, hiding, and wedging[23] strategies in addition to bandwagoning.[24] In a unipolar international system, small states are likely to engage in strategic hedging. Especially during times of uncertainty, states are able to pursue “strategic hedging”. In a bipolar system, hedging is a rarely-applied strategy. In a multipolar system, small and second-tier powers can adopt hedging as a viable policy. Having all these options, it is assumed that Kuwait is one of the small states in the international system and the ruling family of Kuwait, al-Sabah, prefers to adopt “strategic hedging”. The decision-making elites of Kuwait and other Gulf states favor strategic hedging as a safeguard against threats to their regimes.

Some scholars conflate balancing and hedging; however, there are subtle differences that place hedging somewhere between balancing and bandwagoning.[25] According to Waltz, balancing is the flocking together of weaker sides against the strongest, which is a threat by virtue of its superior capabilities. [26] The goal of balancing is to prevent a rising actor from becoming a hegemon within the region both politically and militarily, but the balancing choices of second-tier states uniquely involves choosing between multiple more-powerful states. Within the scope of balance of power theory, hedging is considered a type of balancing behavior, but is distinct from conventional balancing as well as bandwagoning.[27] The main difference between balancing and hedging is the strategy’s method. Balancing is undertaken to directly counter a rising or threatening country with appropriate measures, whereas hedging aims to prevent a rise in tension or conflict with more powerful and potentially threatening states by sustaining a more collaborative stance with either.[28] Bandwagoning, meanwhile, can be defined as “alignment with the source of danger” to gain benefits and ensure security at the expense of autonomy and opportunities to cooperate with other powers.[29]

Adopting either strategy is risky, however. Balancing has at least two branches: internal and external. The internal one relates to a state’s defense capacity and its internal efforts to increase it. With internal balancing, states try to develop an economic share to build up the structure of the army, augment the defense budget, foster defense policies, and advance defense technology and equipment. On the other hand, the external one is about alignment with an external state in the search for security.[30] Small states are more likely to choose external balancing because of their lack of military and economic resources.[31] The risk and uncertainty related to internal balancing stems from the possibility of destabilization caused by the mobilization of internal resources. The risk and uncertainty related to external balancing stems from the unreliability of alliances. A more powerful state can entrap allies and possibly carry the risk of abandoning one’s allies, thereby resulting in balancing failure.[32] The risk and uncertainty related to bandwagoning, meanwhile, is that a state’s foreign policy autonomy can be undermined by the stronger state as it asserts its power over the weaker state. To make sense of lower-risk alternative policies, scholars have weighed in on concepts such as accomodation, passing the buck, soft-balancing, hard-balancing, and “hedging”.[33]

Hedging is not only distinct from bandwagoning, it is also a strategic option that states employ to find a balance between soft and hard balancing and bandwagoning. It aims to open up a strategic choice for states; it does not force states to choose either balancing or bandwagoning, instead offering states time to determine their position in the international power constellation and afford them the possibility of preserving a favorable status quo. Rather than forcing states to choose sides or commit wholesale to risky policies, strategic hedging allows states to adopt diverse security strategies and reduces potential risks and uncertainties that can result from changing power dynamics both regionally and globally.[34] Hedging is ultimately chosen when a state wishes to decrease risks and uncertainties when balancing or bandwagoning are not sufficient responses to allay them, or when fully committing to either of these strategies produces negative outcomes. Even between the concepts of risk and uncertainty, which are mostly similar in terms of context-dependence and subjectivity, there exists a difference regarding probability. Risks can be measured while uncertainties cannot. Therefore, states must identify potential courses of action, which can be a source of uncertainty. In other words, the hedging state also accepts some level of risk by pursuing hedging. This can be interpreted by third parties in different ways. To overcome this, hedging states should be careful to match their actions with their rhetoric. Consequently, states choose the hedging strategy when there exist risks and uncertainties.[35] For this reason, hedging is ideally suited for explaining the foreign policies of small states.

When choosing which states to hedge, states may look beyond military security and base their hedging decisions on other metrics, such as the three primary sources introduced by Tessman and Wolfe,[36] which are economic capacity, military power, central government or decision-making capability. Mohammad Salman and Gustaaf Geeraerts also suggest that states may base their hedging decisions on a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange and gold reserves, government debt, military expenditure, growth of military arsenal, and democracy.

IR scholars are keenly following the shifting global balances of power. The US’ retrenchment policy, the significant rise of China, Russia’s turn to the Middle East through the Syrian civil war and its assertive foreign policy, as well as debates over the EU and its future have led many analysts to re-examine the geopolitical rivalry in the world and in the Middle East. The impulses of great powers during this shift have been analysed by many realist scholars, but the Gulf states’ behaviors have yet to be studied. What has been studied is the strategic choice of behavior regarding the global shift of power dynamics, but this is mostly examined in terms of alignment or realignment.

Adopting hedging as an analytical concept affords us the opportunity to explore the changing dynamics of the distribution of power in the regional and international order, which have caused not only a global change of power, but also shifts between actors within specific regions like the Middle East, and which are of great consequence for small states. Great powers and even regional powers have been exercising pressure on small states to express their positions, especially in times of crisis[37] as was seen during the Gulf crisis. Kuwait was restrained by Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Qatar regionally, and the US internationally.

The new regional order in the Middle East following the Arab uprisings is rife with uncertainties. Therefore, many actors have adopted new policies to prepare for a new regional order. The regional distribution of power is more important for small powers since for those powers, geographical proximity with rising powers is highly concerning. For example, Kuwait does not concern itself with the rise of Brazil, but does so with that of Saudi Arabia. Therefore, hedging can be pursued by being concerned not with polarity and power status per se, but with geographical proximity and regional power distribution. Changes in extant balances have resonated very strongly with small Middle Eastern states, causing them not only to review their current relations, but also to reevaluate their foreign policy options. Balancing, containment, bandwagoning, buck-passing and neutrality can be considered such options for those countries to choose.

4. Hedging as a Survival Strategy for Kuwait

Kuwait has been struggling to maintain its position as a neutral country in the face of intensifying rivalries among the Gulf states. Even though the country has been insistently following a neutral policy, tensions among the regional actors have forced Kuwait to take sides or approach certain actors. During the political and economic blockade initiated by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain against Qatar, Kuwait experienced serious concern over possible effects of the crisis. Especially in the wake of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s aggressive attitude, Kuwait has tried to eliminate potential threats by developing close relations with regional and international actors.[38] In fact, Kuwait has historically experienced similarly weak positions. Kuwait confronted threats to the monarchy during the 1950s and 60s from the rising tide of Arab nationalism in the region, while seeking to protect itself from the regional fallout of the Iranian revolution in 1979. During the Gulf War, Kuwait was invaded by Iraq and the country was forced to remain under the security umbrella of Western powers such as the United States, as well as its allies in the region, such as Saudi Arabia.[39] The Western security umbrella and alliance with Saudi Arabia was crucial for Kuwait to secure its regime. The Kuwaiti leadership was concerned about the new developments, such as the instability in the region unfolding after the Arab revolutions of 2011 and the expansion of Iran’s sphere of influence. This political conjuncture has forced Kuwait to adhere to a hedging strategy. The literature argues that the hedging strategy is generally utilized by secondary or small, weak states when facing two possible situations. The first one is an ascendance of crisis between the hegemon and hedging states. The second is a hegemon ceasing policies that provide subsidies and public goods to hedging states.[40] We argue that Kuwait’s hedging strategy, which aims to protect the country from possible threats arising from intra-Gulf disagreements, can be analysed using three levels of analysis: international, regional and sub-regional.

Following the Arab revolutions, the Gulf countries, including Kuwait, had to adapt to the new political conjuncture in the region. These policy revisions were also responding to the changing policies of extraregional powers like the US, as well as those of other Middle Eastern states. As an example, the United States’ policies during the Obama administration were seriously damaging for US-Gulf relations. Gulf states, which relied on Washington for decades to ensure their security, lost their confidence in US leadership during the Obama presidency. While this break in trust was acutely felt by Saudi Arabia, countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, and Kuwait felt the need to develop alternative alliances and coalitions, fearing that Obama-era policies would become permanent. The US’ retrenchment in the Middle East led these countries to more seriously consider Russia and China, two globally rising powers with growing influence, as alternatives to the US.[41]

Another transformation in global politics vis-a-vis the Gulf region is Russia’s activities aimed at increasing its presence in the Middle East and the Gulf.[42] Moscow considered the process that started with the Arab revolutions as a serious opportunity to gain more influence and thus became a permanent actor in the region, especially through its military engagement in Syria since 2015. On the other hand, aware of the uncertainties in the relations between the US and the Gulf states, Russia has sought to cultivate its relations with Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Russia’s disposition towards the Middle East and the Gulf region is not temporary, and Moscow’s pursuit of long-term goals has made it a possible ally for the countries in the region.

Another dynamic that led the Gulf countries to seek other global partners is the rise of China.[43] Beijing has long been competing with and has become a serious regional and global rival to the US. Therefore, the countries in the Gulf region have paid more attention to China’s rising agency in global politics. The relationship between the Gulf countries and China is particularly important from the purview of energy security since China’s growing economy renders it one of the most avid consumers of Gulf energy. Additionally, China has been developing its military capacity, paving the way for a more active role in both the Middle East and Africa. Therefore, the Gulf countries have a vested interest in improving their relations with China. The recent increase in high-level visits between the leaders of the Gulf countries and the Chinese administration can be viewed as an indicator of this sentiment.

Regional-level developments have also influenced Kuwait’s decision to adopt a new foreign policy. The rise of new actors as well as a reshuffling in the regional alliance system has triggered a possible transformation, by which the decades-long status quo would change. The most important of these is undoubtedly the new political environment that was created in the period following the Arab revolutions. The popular uprisings that began in December 2010 in Tunisia and then spread to many other countries in the region led to a new political atmosphere in the Middle East. In this new political environment, previously inconsequential actors like the Muslim Brotherhood became more important players in regional politics, thereby triggering anxiety and uncertainty for the Gulf monarchies, which have been in power for many years. In the period following the Arab revolutions, the increasing level of instability at the regional level and the increasing strength of non-state actors have called into question the legitimacy of these regimes. Another new dynamic of the Arab revolutions for the Gulf states is the increasing regional influence of Iran. Kuwait was one of the countries that considered Iran’s increasing influence as a concern since at least 30% of its population is Shia. This uncertainty, propounded by new and unpredictable actors, has become a threat for Kuwait and therefore, like other countries in the region, Kuwait has sought alternative foreign policy strategies in order to ensure the security of the regime. Thus, Kuwait also hedges Iran.[44]

In the aftermath of the Arab revolutions, sub-regional developments have also impelled foreign policy innovation for Kuwait. The first of these developments is that Saudi Arabia abandoned its traditional foreign policy track[45] in favor of a more aggressive one.[46] Saudi Arabia has traditionally dictated to the other Gulf countries to align with Riyadh, but has redoubled its efforts in the post-2011 period. The Riyadh administration took a counter-revolutionary position against the Arab revolutions and expected other countries in the Gulf to follow suit. Riyadh, which played an important role in terminating the Egyptian people’s revolution with a military coup, pressured countries like Kuwait and Bahrain to provide financial support to the Sisi regime that came to power after the coup. This continued during the reign of King Salman, who took office after King Abdullah's death in 2015. Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy became more assertive in the early period of King Salman’s rule. Together with the UAE, Saudi leadership initiated a military campaign to fight against the Iranian-supported Houthis in Yemen. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi requested the support of the countries in the Gulf for the military operation in Yemen. In contrast to its policy of non-interference in regional conflicts, Kuwait joined the coalition against the Houthis in Yemen, possibly as a result of the pressure by the Saudi administration. Although it fulfills Saudi Arabia’s demands, the Kuwaiti leadership is concerned with the Riyadh’s regional policies.

These concerns have come to light with the political and economic blockade of Qatar initiated by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain. It was a serious disappointment and source of discomfort for the Kuwaiti leadership to witness three Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members politically blockade a fellow neighbor, Qatar. Oman was also not happy with this move and did not support the blockade. The Kuwaiti and Omani administrations, which traditionally had political leanings different from those of the Saudi and Emirati leaderships, became concerned that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi could put pressure on them in the case of an exacerbated disagreement in response to other regional actors such as Iran and Turkey.[47] In order to prevent such a possibility, Kuwait sought to foster new links both at the regional and global levels and took initiatives to this effect.

Another sub-regional factor affecting Kuwait’s foreign policy is the ambiguity surrounding the future of the GCC. The initial mistrust among the GCC members started with the 2014 crisis when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain recalled their ambassadors from Qatar. During the crisis, the weaker GCC states realized that the alliance system in the region was fragile and could break in the case of a serious crisis. The 2017 blockade on Qatar by its neighbours was another development that threatened the unity among the GCC states. As a result of the crisis, the members of the GCC started to question the future of the alliance. Additionally, the divergence that exists among the member states in their approaches on many issues has gradually deepened. While Saudi Arabia and the UAE have sought to undercut Turkey, Qatar has instead opted to develop a strategic alliance with Ankara. Kuwait, too, has been looking to increase its cooperation with Turkey and Iran. Therefore, the loss of harmony between the members of the GCC, both in foreign policy and intra-regional politics, not only cast doubts about the viability of the organization, but have concurrently fuelled Kuwait’s insecurities, prompting it to pursue, as we discuss in the next section, a hedging strategy.

5. Kuwait's Dual Hedging Strategy towards China and Turkey

Kuwait is one of the small states in the Middle East due to its economic dependence and growing security concerns after the Arab Spring; with these and many other dimensions in mind, it started to pursue the hedging strategy. The main purpose of this strategy is to “avoid having to choose one side at the expense of another”. Hedging strategies manage to be effective and sustainable because they avoid antagonising any other states. Hedging also provides assurance when part of an engagement fails, emphasizing cooperation as a primary objective.[48] In doing so, these strategies also aim to prevent other states from undermining the security environment. Meanwhile, the hedging state enjoys relatively peaceful relations, enough to implement a coherent long term plan[49] to develop its competitive ability (military and economic) while avoiding direct confrontation with the leader of a unipolar system.

Through hedging, states are able to implement a counter-acting policy. Such a policy assures them of at least two usable tactics. The first one is to strengthen economic cooperation with others. The second is to increase military capability and alignment to confront potential adversaries, including states and non-state actors. Kuwait started to increase its military capabilities and enhance diplomatic ties with both international (China) and regional (Turkey) actors. Therefore, it is hedging security. Kuwait’s strategy towards China can be defined as “soft hedging”. It is a mixture of diplomatic balancing and economic bandwagoning.[50] Kuwait’s strategy regarding Turkey, meanwhile, can be defined as “economic hedging”. It is a mixture of military bandwagoning and economic balancing.[51] We argue that by having a new approach to the hedging strategy but also staying within the main line of theory, Kuwait hedged China’s rise itself by maintaining good relations with the country. On an international level, by hedging China, Kuwait has also prepared itself for the risks and uncertainties resulting from the US’ retrenchment policy. At the regional level, Kuwait also hedges Turkey by deepening its military and economic ties with Ankara. This choice of policy also allows Kuwait to hedge the risks that could result from regional ambiguity. In other words, to deal with the security concerns and risks overflowing since the Arab revolutions, Kuwait was inclined to approach Turkey. This rapprochement allows Kuwait to balance Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates’ aggressive foreign policy doctrines. The assertive foreign policies of Saudi Arabia and the UAE have severely damaged the Gulf Cooperation Council, to which Kuwait attaches importance. The war on Yemen and the blockade of Qatar also pushed Kuwait to lean on Turkey militarily, thus demonstrating that there is regional instability and uncertainty. To deal with these challenges at two distinct levels, both the international and regional system, Kuwait launched a dual hedging strategy towards China and Turkey.

5.1. Chinese-Kuwaiti cooperation

The rise of China has been welcomed by Middle Eastern countries due to Beijing’s far-reaching economic, military, and political capacity. Positive expectations are held especially by the Gulf countries. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, and Oman are among those, but Kuwait is one of the most outstanding members of the GCC that is inclined to form an alliance with China. By forming an alliance or engaging more institutionally with China, Kuwait aims to deal with two existantial threats. The first one is the confrontation diverted by the Baathist Iraqis under Saddam Hussein’s administration that undermined and confined Kuwait. The second one is originating from Iran. Thus, Iran has also been undermining the Shia population to politicize them against the al-Sabah regime and Saudi Arabia, who has no tolerance towards political neutrality. Therefore, Kuwait has started to adopt new foreign policy principles to eliminate these threats by playing the diversity card in foreign policy.

It is the hedging strategy that prevents confrontation between Kuwait and the US, as well as the capture of Kuwait by China’s yoke. During the Obama administration, US foreign policy did not satisfy its allies, especially in the Gulf, due to its reluctance to engage with Middle Eastern politics, resulting in US allies adopting hedging strategies. During this period, the US declined to aid its allies. More specifically, the US aided neither the Mubarak regime of Egypt nor the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia. When the pro-revolutionary movements became a threat for the Gulf regimes, the monarchies understood that the US was unwilling to help shore up their regime security. Additionally, the US Congress and some democrats in the US have criticized the regimes in the Gulf, which compelled their rulers to evaluate the US as an unreliable partner, rather than as an ally. In this sense, China does not pose a threat to the Gulf monarchies. Beijing has a long-term vision and has no stakes in the domestic affairs of the Gulf countries. Therefore, upon assessing the relations between Kuwait and China using a cost-benefit analysis, it becomes clear that Beijing has been providing benefits to three fields of vital importance to the Gulf monarchies.

The first field is economy. Changes in the global financial sector, such as the crisis in 2008 and challenges in regional/local oil sectors, pushed some Arab countries to diversify their policies. As a result, the “Look East” idea has emerged as an alternative to the Gulf states. To transform Kuwait into “New Kuwait” via the 2035 Vision, the al-Sabah regime has intensified its relations with China. Commerce, culture, logistics, finance, tourism and other sectors are among the cooperative fields between Kuwait and China. Additionally, China’s dependence on Gulf oil has increased its diplomatic ties with Kuwait. China’s need for energy has resulted in several agreements. Moreover, Kuwait has welcomed foreign investments, especially from China. In this sense, cooperation between the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) and the China Investment Corporation (CIC) has grown.[52] There have thus been several agreements signed by the two countries. For example, Kuwait and China have signed an agreement to accelerate and facilitate the completion of the Silk City project, which promises a major economic boon.[53] It is no surprise that since 2009, Kuwait has been looking towards the East, particularly to China, in terms of political and economic outreach.[54] However, since 2018, more agreements have been signed and both countries have agreed to establish a strategic partnership.[55] Therefore, it can be argued that Kuwait has been more enthusiastic with regard to improving its relations with China rather than its relations with the US. As a result, Kuwait has invested significantly in its economic relations with China.

The second field is the military. The unpredictability of the US’ security policies in the region has had a negative impact on Kuwait. By withdrawing its presence from Syria and recalling several Patriot missiles from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan, and Bahrain, the US administration unsettled Kuwait’s leadership.[56] In contrast, China has been supplying conventional weapons, drones, and other military equipment to Kuwait without any concern over Kuwait’s domestic issues.[57] Moreover, there has been strong military training cooperation between the two countries. Kuwait is the first GCC member to sign a military cooperation agreement with China.[58] Also, there is a historical rapprochement between the two countries. After Saddam’s invasion, Kuwait signed defense and security pacts with the five permanent members of the UNSC and gained a closer relationship with China. Instead of the US or UK, Kuwaiti authorities bought howitzers from China.[59] Kuwait is clearly eager to have close relations with China.

The third field is politics. Being the first GCC member to recognize and establish diplomatic relations with China on 22 March 1971, Kuwait has the longest relationship with the Beijing administration. Having a close relationship with China provides at least two benefits to Kuwait. The first one is that it enhances Kuwait’s international influence. Beijing has a permanent seat at the UN Security Council, which leverages China’s power into play in the international arena. The second one is related to domestic politics. China has no concern over civil rights or humanitarian issues in Kuwait or elsewhere in the Gulf. That makes China more reliable than the US in the eyes of Kuwait. Lastly, the previous crown prince of Kuwait, Nasser Sabah al-Ahmed al-Sabah, has been eager to expand the relations’ range. Trying to transform Kuwait into a modern trade hub, Nasser al-Sabah places great value on China and is therefore enthusiastically pursuing a partnership with China.[60]

5.2. Turkish-Kuwaiti cooperation

The relationship between Turkey and Kuwait has been positive as the two countries have not experienced any serious crises in recent history. These friendly relations have developed further since the AK Party’s coming to power in Turkey in 2002. In fact, President Erdogan’s special interest in Kuwait has allowed the relations between the two countries to blossom into a strategic partnership. This situation became noticeable following the Arab revolutions as the two countries signed a number of cooperation agreements in different sectors. In 2013, an agreement was signed between the two countries on security and military cooperation. Other agreements in the fields of energy, construction, industry, and culture soon followed.

This situation accelerated especially after the Gulf Crisis in 2017. Kuwait’s now-deceased Amir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah had visited Turkey in 2017. The Kuwaiti Amir al-Sabah and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan signed an additional six agreements on various sectors. In November of the same year, President Erdogan also visited Kuwait, in the aftermath of the Gulf Crisis. The two leaders emphasized that the Gulf Crisis should be resolved and the conflicting parties must work on reducing the tension. During the visit, the Chiefs of the General Staff of the two countries also held meetings and discussed military cooperation. The Turkish-Kuwaiti Cooperation Committee meeting held in Kuwait on October 9-10, 2018, resulted in two agreements, including a new military cooperation agreement that took effect in 2019. These agreements aimed to enhance the military cooperation between the two countries.[61] In this context, several scholars and analysts have argued that a new regional Kuwait-Turkey alliance[62] is poised to begin following the latest agreement stipulating Kuwait’s approval for the deployment of Turkish troops on its territory and the purchase of Turkish defense products.[63]

The close relationship between Kuwait and Turkey can also be seen in the fields of culture and economy. According to a poll conducted in Kuwait in March 2019, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was named the most popular foreign leader. As for tourism, a large number of Kuwaitis choose Turkey as their travel destination, while scores of them buy property in the country. Such developments are signs of Turkey’s increasing popularity in Kuwaiti society. This is also evident in economics in view of the burgeoning economic cooperation between the two countries in recent years. Turkish companies have undertaken more than 30 projects in Kuwait, which together are worth at least 6.5 billion USD. Turkey also attracts Kuwaiti investments. In 2005, Kuwait decided to name Turkey as one of its priority investment targets. In this sense, Kuwait became one of the top five foreign investors in Turkey.[64]

Why does Kuwait pursue a rapprochement with Turkey? The first reason is the changing nature of alliances and power relations in the Middle East. As Turkey’s importance has become more apparent, the Gulf countries have attempted to rearrange their alliance patterns with Ankara. Some of the Gulf leaders wish to have better relations with Turkey in order to balance other regional actors such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. The second reason is the 2017 blockade imposed on Qatar by its Gulf neighbours: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain. Other smaller Gulf countries such as Kuwait and Oman watched the developments under immense pressure and they became concerned with the actions of these aggressive powers.[65] As a result, these countries decided to establish new relationships with other powerful regional actors such as Turkey and Iran, as well as a number of global players. Finally, the continuation of historical disputes between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait has been a source of concern for the latter. This urges Kuwait to be cautious in the face of Riyadh and encourages it to secure itself in case of possible tension with different alliances.

6.Conclusion

Strengthening its alliance with China, Kuwait uses hedging to prevent the risks and uncertainties left by the US policy of retrenchment from the Middle East. On the other hand, by strengthening its alliance with Turkey, Kuwait uses hedging to prevent Saudi Arabia from leading or dominating the regional order, while also developing its economic and security ties with both the US and Saudi Arabia.

The first benefit is that this strategy reduces the risks and uncertainties originating from the rising power of Saudi Arabia, which has been conducting assertive foreign policy both regionally and internationally since 2015. By allying with Turkey, Kuwait does not directly target Saudi Arabia. Additionally, because of this cooperation, Kuwait’s relations with Riyadh are not harmed. In deepening its security alliance with Turkey, Kuwait wants to make sure that it has a reliable partner in the case of a threat from its GCC partners, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Kuwait’s actions in this regard aim to prevent a direct confrontation with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in order to avoid sharing the same fate as Qatar.[66]

The second benefit is that this strategy reduces the risks and uncertainties originating from the leader of the unipolar system, the US. The US’ pivot to Asia under the Obama administration and its concomitant retrenchment from the Middle East were deeply troubling for Kuwait, prompting the need to find another major power, in this case China, to secure itself. By allying and cooperating more with China, Kuwait does not directly target the US because its cooperation with the US still continues. So, Kuwait’s hedging strategy focuses on including new powers into its foreign policy orbit while keeping traditional allies such as the US on its side.

This study has attempted to apply a concept from finance to international relations. As such, previous applications of the concept were highly useful in explaining the alignment and balancing behaviors of states. The present study aims to help IR scholars understand what drives some states to seek new alliances, either as replacements for or additions to existing alliances. Strategic hedging has been increasingly used in explaining such situations. It is the aim of this study to focus on Kuwait’s foreign policy behavior and its decision to form new alliances with some regional and international actors.

The findings of this study can be extended to other cases. It can be argued that the concept of hedging can successfully explain the foreign policy behavior and relationship pattern of Qatar and its policies towards regional and global actors. Qatar’s hedging strategy can be understood along patterns similar to those of Kuwait and with similar cases, namely Turkey and China. Meanwhile, Turkey’s foreign policy is suited for such analysis as Ankara’s rapprochement with Moscow can offer invaluable insights about hedging behavior.

Alagöz, Emine Akçadağ. “Blue-Water Navy Program as a part of South Korea’s Hedging Strategy.” Güvenlik Stratejileri 13, no. 25 (2017): 65–97.

Al- Saleh, Abdullah R. “Conflict Analysis: Exploring the Role of Kuwait in Mediation in the Middle East.” Master Diss., Portland State University, 2009.

Bowen, Wyn, and Matthew Moran. “Iran’s Nuclear Programme: A Case Study in Hedging?” Contemporary Security Policy 35, no. 1 (2014): 26–52.

Cafiero, Giorgio. “Kuwait’s New Strategy: Pursuing a Partnership with China.” Inside Arabia, October 8, 2018. https://insidearabia.com/kuwait-strategy-pursue-partnership-china/ .

Cafiero, Giorgio, and Cinzia Bianco. “Kuwait Looks to Turkey, But Hedges its Bets.” Inside Arabia, November 13, 2018. https://insidearabia.com/kuwait-looks-turkey-but-hedges-bets/ .

Chaziza, Mordechai. “China’s Strategic Partnership with Kuwait: New Opportunities for the Belt and Road Initiative.” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 7, no. 4 (2020): 501–19.

–––. “Strategic Hedging Partnership: A New Framework for Analyzing Sino–Saudi Relations.” Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 9, no. 3 (2015): 441–52.

Chan, Steve. Looking for Balance: China, the United States, and Power Balancing in East Asia. California: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Crawford, Timothy W. “Preventing Enemy Coalitions: How Wedge Strategies Shape Power Politics.” International Security 35, no. 4 (Spring 2011): 155–89.

Eberling, George G. China’s Bilateral Relations with Its Principal Oil Suppliers. USA: Lexington Books, 2017.

Fusaro, Peter, and Tom James. Energy Hedging in Asia: Market Structure and Trading Opportunites. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Ghafouri, Mahmoud. “China's Policy in the Persian Gulf.” Middle East Policy 16, no. 2 (Summer 2009): 80–92.

Goh, Evelyn. Meeting the China Challenge: The U.S. in Southeast Asian Regional Security Strategies. Policy Studies no. 16. Washington, DC: East-West Center, 2005.

Gresh, Geoffrey F. Gulf Security and the U.S. Military: Regime Survival and the Politics of Basing. California: Stanford University Press, 2015.

He, Kai. “Institutional Balancing and International Relations Theory: Economic Interdependence and Balance of Power Strategies in Southeast Asia.” European Journal of International Relations 14, no. 3 (2008): 489–518.

–––. “Undermining Adversaries: Unipolarity, Threat Perception and Negative Balancing Strategies after the Cold War.” Security Studies 2, no. 2 (2012): 154–91.

Heiran-Nia, Javad, and Somayeh Khomarbaghi. “Turkey and Kuwait: A New Regional Alliance?” Lobelog, October 25, 2018. https://lobelog.com/turkey-and-kuwait-a-new-regional-alliance/ .

Hook, Steven W, and Tim Niblock. The United States and the Gulf: Shifting Pressures, Strategies and Alignments. Berlin: Gerlach Press, 2015.

Huwaidin, Mohamed Mousa Mohamed Ali Bin. China’s Relations with Arabia and the Gulf 1949-1999. New York&London: Routledge, 2002.

Jackson, Van. “Power, Trust, and Network Complexity: Three Logics of Hedging in Asian Security.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 14, no. 3 (2014): 331–56.

Karasik, Theodore, and Tristan Ober. “Kuwait and The China-U.S. Geopolitical Rivalry.” Lobelog, January 30, 2019. https://lobelog.com/kuwait-and-the-china-u-s-geopolitical-rivalry/.

Koga, Kei. “The Concept of “Hedging” Revisited: The Case of Japan’s Foreign Policy Strategy in East Asia’s Power Shift.” Internaional Studies Review 20, no. 4 (2017): 633–60.

Korolev, Alexander. “Russia in the South China Sea: Balancing and Hedging.” Foreign Policy Analysis 15, no. 2 (2019): 263–82.

–––. “Systemic Balancing and Regional Hedging: China-Russia Relations.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 9, no. 4 (2016): 375–97.

Kuik, Cheng-Chwee. “The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s Response to a Rising China.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 30, no. 2 (2008): 159–85.

Lake, David. “Anarchy, Hierarchy, and the Variety of International Relations.” International Organization 50, no. 1 (1996): 1–33.

Medeiros, Evan S. “Strategic Hedging and the Future of Asia Pacific Stability.” The Washington Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2005): 145–67.

Niazi, Khizar. “Kuwait Looks towards the East: Relations with China.” The Middle East Institute Policy Brief No: 26, September 1, 2009. https://www.mei.edu/publications/kuwait-looks-towards-east-relations-china.

Richter, Thomas. “New Petro-aggression in the Middle East: Saudi Arabia in the Spotlight.” Global Policy 11, no. 1 (2020): 93–102.

Rieger, René. Saudi Arabian Foreign Relations: Diplomacy and Mediation in Conflict Resolution. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Roy, Dennis. “Southeast Asia and China: Balancing or Bandwagoning.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 27, no. 2 (2005): 305-–22.

Salman, Mohammad, and Gustaaf Geeraerts. “Strategic Hedging and China’s Economic Policy in the Middle East.”China Report 51, no. 2 (2015): 102–20.

Salman, Mohammad, Moritz A. Pieper, and Gustaaf Geeraerts. “Hedging in the Middle East and China U. S. Competition.” Asian Politics & Policy 7, no. 4 (2015): 575–96.

Schweller, Randall L. “Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In.” International Security 19, no. 1 (1994): 72–107.

Sim, Li-Chen. “Russia’s Return to the Gulf.” In External Powers and the Gulf Monarchies, edited by Jonathan Fulton and Li-Chen Sim. New York & London: Routledge, 2019.

Snyder, Glenn. “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics.” World Politics 36, no. 4 (1984): 461–95.

Telci, Ismail Numan. “Müttefiklikten nüfuz mücadelesine Suudi Arabistan-BAE ilişkileri.” Anadolu Ajansı, February 22, 2021. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz/muttefiklikten-nufuz-mucadelesine-suudi-arabistan-bae-iliskileri/2152733.

–––. “Qatar-Gulf Rift: Can Riyadh Be Triumphant?” Al Jazeera, June 9, 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/6/9/qatar-gulf-rift-can-riyadh-be-triumphant.

Telci, Ismail Numan, and Omair Anas. “Towards a New Security Architecture in the Gulf?” ORSAM Series on Middle East in Transition, Ankara, September 2020.

Tessman, Brock, and Wojtek Wolfe. “Great Powers and Strategic Hedging: The Case of Chinese Energy Security Strategy.” International Studies Review 13, no. 2 (2011): 214–40.

Tran, Thi Bich, and Yoichiro Sato. “Vietnam’s Post-Cold War Hedging Strategy: A Changing Mix of Realist and Liberal Ingredients.” Asian Politics & Policy 10, no. 1 (2018): 73–99.

Walt, Stephen. The Origin of Alliances. Ithaca, NY: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Waltz, Kenneth. Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Wolfe, Wojtek M. “China’s Strategic Hedging.” Orbis 57, no. 2 (2013): 300–13.

Yoshihara, Toshi, and James R. Holmes. “China’s Energy-Driven Soft Power.” Orbis 52, no. 1 (2008): 123–37.