İsmail Erkam Sula

Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

This article covers the disciplinary debates on ‘global’ IR and the self-reflections of IR scholars about the state of the discipline in Turkey. It argues that high quality methodological training can contribute to overcoming the dissatisfaction felt by scholars of IR in Turkey. It suggests that inclusion of IR knowledge produced in the non-core into the ‘Global’ pool can be achieved through local ‘revolutions’, and that the potential for progress in this direction lies in methodological improvement and data-collection projects. The article offers three exemplary data projects to crystalize the argument: the Social Sciences Data Repository, the Global Security Database (GloSec) and the Global Risk Assessment Dataset (GRAD). These projects aim to: disseminate data-based research and encourage data sharing among scholars in Turkey, train prospective IR scholars to produce research based on clear, replicable, and rigorous methodology in Turkey, encourage graduate students in Turkish universities to have a global scholarly outreach and talk to the global scholarly community, and contribute to IR scholarship with these local pedagogical and academic experiences. Two separate groups of researchers composed of graduate students from various universities across Turkey are trained in the ways of research design, the fundamentals of data collection, and writing research papers based on rigorous methodological design, data, and replicable findings. Thus, the paper not only discusses the diagnoses in the literature regarding the shortcomings of the International Relations discipline in Turkey, but also offers concrete directions for a potential treatment.

1. Introduction

The state of the IR discipline has been a debated topic among IR scholars for approximately four decades. These debates started with criticisms of ‘US-centrism’, continued with the call for a more inclusive understanding of scientific knowledge production in IR, and evolved into the call for further inclusion of the ‘non-core’ or ‘periphery’ in the discipline. The shifting nature of these debates and how they have transformed already indicate that the IR discipline has truly become more inclusive in time, but as some scholars would argue, still not necessarily ‘international’ or ‘global’. Hence, scholars have recently started to discuss the possibility of globalizing IR. The call was for IR scholars across the world to challenge and overcome the disciplinary boundaries set by American and Western IR scholars, thereby advancing a more inclusive and universal IR discipline. Accordingly, the literature has produced abundant studies on definitions of ways to achieve ‘global IR.’

As debates on the state of the art continued in the literature internationally, IR scholars in Turkey also had time for some ‘self-reflection’, especially regarding the state of the IR discipline in the country. Since the early 2000s, IR in Turkey has been assessed in a few studies on critical topics, including but not limited to the need for improving the theoretical contributions made by Turkish IR scholars, the underdevelopment of ‘homegrown theorizing’, and the need for improving methodological quality and training. The overall debate on IR in Turkey usually revolves around diagnosing problems within the literature with occasional suggested prescriptions to overcome them. Since this discussion has been going on for some time, we have a considerable number of prescriptions in the literature. While reviewing, analyzing, and building on some of these prescriptions, this article comes up with its own suggestions that aim to connect the disciplinary debates on Turkey’s IR with the debates on global IR.

I suggest that we may have already used much time in the diagnosis and prescription phase and overlooked the next steps constituting the treatment of these issues. Combining my observations with the self-reflections of Turkish IR scholars, I argue that the ‘underdevelopment’ of Turkey’s IR discipline is related not only to the lack of theoretical studies or lack of ‘quantitative’ methodology, but to a wider problem as well: studies frequently have an inability to establish three interrelated connections between (1) metatheory and theory, (2) theory and the empirical application, and (3) methodology and methods. Following some of the existing ‘prescriptions’ in the literature, I argue that by implementing high quality methodological training, which would enable IR students to establish these three connections, we can better foster a scholarly community that produces replicable research, homegrown theorizing, and takes part in the ‘center/core’ of global IR. To crystalize the argument and move beyond prescription, I also offer examples from ongoing projects, together with the details of their research and teaching designs.

I suggest that ‘data-collection’ may serve as a good starting point for methodology training in Turkey and discuss the scope of the Social Sciences Data Repository, the Global Security Database (GloSec) and the Global Risk Assessment Dataset (GRAD) as learn-in-action research projects. These three projects can serve as examples for the dissemination of data-based research and enable data-sharing among Turkish scholars, thereby aiding the accumulation of IR knowledge in Turkey. The data-collection projects aim at training prospective/early-career IR scholars in data-collection, research/project design, proposal writing, and other academic activities (teamwork, conference application… etc.). One might assume that these skills are developed in graduate programs at most universities; however, the scholarly output and the dissatisfaction in the ‘self-reflections’ summarized below indicate that the IR discipline in Turkey might benefit greatly from such ‘data-sharing’ platforms, as well as methodological ‘train-in-action’ and ‘data-collection’ initiatives.

The first part of the article reviews debates on the state of the art in IR literature. The second part assesses the self-reflections of Turkish IR scholars, their diagnoses on the shortcomings of the IR discipline in Turkey, and their suggestions to overcome these limitations. The third part gives examples from ongoing projects that may help overcome some of the shortcomings of the IR discipline in Turkey. The article concludes that high quality methodological education is of key importance to self-reflection in the periphery and for reclaiming IR from the core.

2. From ‘Truly International’ to ‘Global’: Discussion of the ‘State of the Art’ in IR

The debate on fostering a truly ‘international’ IR discipline has continued for a considerable amount of time. Criticisms against the hierarchies, dependencies, boundaries, and geographical limitations reinforced within the discipline began around the 1970s with discussions of whether IR is an ‘American’ discipline. Since then, though seldom in the beginning, IR scholars have analyzed the development of the discipline in the non-core or non-American parts of the world. By 1977, Hoffman had referred to the formation of IR as a field autonomous from political science. However, he stipulated that such development only grounded IR as a ‘discipline’ in the United States, making it an ‘American’ social science. Presenting his dissatisfaction with the state of the IR discipline at that time, he suggested that the discipline should move away from the American ‘superpower’ perspective and towards other parts of the world.[1] In 1980, Palmer claimed that the IR discipline is not ‘an American social science.’[2] In his review of the then-‘state of the art’ he observed that the IR discipline was rapidly becoming ‘truly international’ and it should continue to do so through transnational dialogue among scholars. Palmer also appreciated the International Studies Association’s (ISA) efforts in creating significant ‘trans-Atlantic dialogue’ and intent to transform this dialogue into a transnational one “not confined simply to American and British scholars (…) [but also one in] which scholars all over the world will participate.”[3] Such discussion has also revolved around ISA, which is one of the main professional associations of the scholars in the discipline.

In the 1990s, various scholars claimed that neither the ISA nor the IR discipline was ‘truly’ international. For instance, in her presidential address in 1995, Susan Strange argued that the ISA can serve as a “hearing-aid” for American scholars, even though they are not aware that they need it: “You -as authors and too often as editors of professional journals- appear to be deaf and blind to anything that's not published in the U.S.A. Ask yourself when you last quoted an author or a journal outside the U.S. How many non-American journals do you look at?”[4] Strange calls upon ISA members to develop an indiscriminatory forum open to all national backgrounds and disciplines conducting international studies. Building on these previous arguments, in 1998, Waever claimed ‘American Hegemony’ continues to influence the theoretical profile of the discipline.[5] While he acknowledges that IR has become a ’globalized’ discipline with the establishment of regional professional associations, he also observes how ‘American’ theories travel across the rest of the world. He claims that the emerging national IR communities are importers of knowledge, in a sense, suffering a huge trade deficit against the export of American knowledge. Waever puts forward the necessity of the ‘de-Americanization of IR’ to talk about a global non-asymmetrical disciplinary development. “The best hope for a more global, less asymmetrical discipline lies in the American turn to rational choice, which is not going to be copied in Europe.”[6] Waever seems to be more hopeful about European IR, in which he sees a professionalization without Americanization. However, he claims, this professionalization is in contrast with what is happening in the ‘true periphery’, where the main aim still was to reach America.[7]

In 2000, Steve Smith wrote that the discipline of IR is “still an American Social Science.”[8] He presents how American understandings of epistemology and methodology continue to be dominant in IR, de-legitimizing other understandings of theory development and scientific knowledge production. He claims that the US IR community dominates IR theory and exports their adherence to one dominant theory, rationalism. Comparing the state of the discipline in the US and UK, Smith concludes that in the UK “IR is a far more pluralist subject, with no one theoretical approach dominant.”[9]

Scholars also continued to criticize the International Studies Association for being ‘North American’ and not ‘International’. While acknowledging the increase in paradigmatic debates in the IR discipline, Aydinli and Mathews argued in favor of the need for more attention on the divides between core and periphery.[10] The authors call for more dialogue between the core and periphery and claim that “in the post–Cold War era of increasing globalization, neither policy prescriptions nor theory construction in IR can afford to ignore the perspectives of the true periphery that lies outside of Europe and North America.”[11] Based on data collected from leading scholarly journals, the authors argue that the ‘core’ does not fully acknowledge the contributions made by the periphery to the discipline. The same observation also holds for highly theory-oriented journals: “While there is overall limited dialogue, this study also shows that the more highly theory-oriented a journal is, the less likely, on average, it is to include contributors from outside of its group.”[12] The authors argue that leading journals and organizations have not been able to break the dominance of the US in IR-related theoretical debates, and call for increased dialogue between the core and periphery by assessing both sides’ responsibilities.[13]

In 2003, Arlene Tickner called for “Seeing IR Differently.”[14] In her review of the then-recent literature, Tickner observed that the debates over the state of the IR discipline continued in three complementary ways. The first was the debate between post-positivists and mainstream IR theorists on the latter’s dominance over the ways of knowledge production. The post-positivist critiques demanded an expansion of the disciplinary boundaries towards a more inclusive understanding of knowledge production. The second debate was the discussion built on the history and sociology of science discussing “how social factors internal and external to the community have influenced IR thinking.”[15] Lastly, the third group of studies discussed the national variations within the IR discipline, mainly comparing the US and Europe. Tickner observes the emergence of a fourth group of studies arguing for “the need to think differently about IR in non-core settings.”[16] According to Tickner, this fourth group of studies claims that the “terminology, categories and theories” of the ‘core’ do not correspond with the realities of the ‘non-core’ or, as she calls it, the “Third World”.[17] Tickner argues that listening more closely to the third world interpretations of international relations would decrease dissatisfaction stemming from the “intellectual crisis in IR” and enhance our knowledge and understanding of world problems.[18] She calls for a dialogue between the third world and the ‘core’, bringing third world local knowledge into the understanding and the theorizing of international relations, thereby creating a new language of academic studies and an alternative approach to rethinking IR.[19]

From the 1970s to the early 2000s, debates on the state of the IR discipline have started with criticisms of US-centrism, evolved with the call for a more inclusive understanding of scientific knowledge production in IR, and continued with the call for the inclusion of the non-core into the discipline. The ways in which these debates have evolved indicate that IR has truly become more inclusive in time, but as some scholars would argue, the discipline is still not necessarily ‘international’ or ‘global’. By the late 2000s, scholars following this trajectory have argued for the inclusion of ‘IR beyond the West’, ‘Post-Western’, and ‘non-western’ in the study of IR.[20] Criticisms of the state of the literature and theorizing in IR have evolved from ‘American-centrism’ to ‘Western-centrism” and ‘Eurocentrism.’[21] Analyzing the state of the discipline with an emphasis on the relationship between the ‘core’ (or center) and non-core (or periphery) has also led to the recent debate on ‘Globalising’ IR.

As part of his presidential address at the ISA conference, Acharya puts forward a claim to develop a more inclusive discipline that incorporates diverse approaches developed in the non-core and that transcend the division between the West and the Rest.[22] He observes that the IR discipline “does not reflect the voices, experiences, knowledge claims, and contributions of the vast majority of the societies and states in the world, and often marginalizes those outside the core countries of the West.”[23] In 2016, as part of the Presidential Issue of International Studies Review, Acharya defines Global IR as an idea that “urges the IR community to look past the American and Western dominance of the field and embrace greater diversity, especially by recognizing the places, roles, and contributions of ‘non-Western’ peoples and societies.”[24] He argues that IR scholarship across the world should challenge and overcome the disciplinary boundaries set by American and Western IR scholars, and thereby advance a more inclusive and universal discipline. The literature has produced abundant studies on definitions of ways to achieve ‘global IR’.[25]

This summary on the evolution of debates on the state of the art in the discipline brings us to the following: ‘self-reflection in the periphery’ and ‘reclaiming IR from the core”. As this discussion is not unprecedented in global IR literature, it is also not unprecedented in Turkish IR literature. While making an assessment on ‘homegrown theorizing’ and the state of the art in Turkey, the following section evaluates Turkish IR’s engagements in self-reflection.

3. Time for Self-Reflection: Diagnosis and Prescriptions

In line with the above-mentioned international literature, a limited number of studies have assessed the state of the IR discipline in Turkey.[26] Aydinli and Mathews offered ‘homegrown theorizing’ as a feasible way to get Turkey’s IR discipline acknowledged by the center.[27] By 2008, they had highlighted the limited improvement in the center-periphery relationship, in which knowledge at the center is transferred to the periphery, since the early 2000s when scholars made solid criticisms of this dependency. The imbalance, or in Waever’s words ‘the trade deficit’, will continue unless the periphery starts bringing original local theories and concepts to the ‘global’.[28] They call for comprehensive studies on the original theoretical paradigms and they focus on the factors, local or otherwise, that hamper the development of such original paradigms in the periphery. Then, the authors assess the state of the art in Turkey and the probable factors that hold Turkey’s IR from becoming truly ‘international’.[29]

Due to certain domestic political and pedagogical factors, the Turkish IR discipline has been established and, for a long time, dominated by scholars that mainly focus on descriptive historical/political studies rather than theoretical ones.[30] Theoretical studies started to emerge only during the 1990s, as an increasing number of scholars in Turkish IR (mostly those having graduate degrees from North American or European Universities) started to affiliate themselves with IR theory and theorizing. Yet, in their interviews with local IR scholars, Aydinli and Mathews found that even those scholars who claim to be ‘theorizing’ are continuing to import theories from the center and make empirical applications of those theories to the Turkish case. Instead of ‘application theorizing’, the authors offer ‘homegrown theorizing’.[31] The difference, they argue, “is not simply its [application theorizing] reference to an existing body of theoretical literature however, but rather the solely confirmative use of that literature – offering your context as another ground for further confirmation of an imported concept.”[32]

Aydinli and Mathews discuss four different ways of theorizing with examples from IR in Turkey.[33] First, pure theorizing aims at finding “coherent explanations for broad phenomena while remaining unattached to specific areas.”[34] Second, homegrown theorizing refers to studies aiming to develop theories bringing “entirely new patterns, understandings, and frameworks of analysis” based on local experiences.[35] Third, application theorizing refers to applying theories developed in the center while using the local as a case study. This is one of the frequently observed approaches among Turkish scholars. Finally, “borrowed works” or translation theorizing refers to the translation of existing theoretical works into the native language to make it “accessible to the average Turkish IR Student.”[36] Based on these four types of theorizing, the authors identify that although theorizing in Turkish IR has increased in the last 15 years, the discipline has not made enough progress in homegrown theorizing. The authors talk about certain ‘core’ and ‘periphery’-related reasons for the underdevelopment of homegrown theorizing in the Turkish discipline. After this diagnosis, they refer to a couple of prospects and ‘prescriptions’ for the theoretical development of the IR discipline. The authors stress some positive improvements, such as the establishment of new IR journals, organization of conferences, and emergence of new funding opportunities. They conclude by offering homegrown theorizing as the path for periphery scholars to reach the center.[37]

Approximately a decade later, Köstem also observes similar limitations to the state of theory in Turkish IR. He states that Turkish IR studies “is still mostly focused on various regional and thematic aspects of Turkey’s foreign relations, with little original theoretical insights.”[38] He argues that “IR theorizing in Turkey by Turkish scholars is rare because now, in the post-Mülkiye era, our minds are occupied only with grand theories and meta-theoretical debates.”[39] He argues that Turkish IR imports theoretical positions from the west, which results in two side-effects: “we tend to either get lost in big theoretical questions as a result of the futile effort to explain all political phenomena with a single grand theory, or simply apply grand theories to issues of Turkey’s international relations.”[40] He observes an inclination towards abstract theoretical debates in Turkish IR, which, he argues, causes fault lines between scholars that adhere to competing theoretical positions. After diagnosing the limitations, he proposes a couple of prescriptions as well. Rather than offering homegrown theorizing, he suggests that IR scholars in Turkey should (1) adopt a theoretically pluralist position and (2) connect “their theoretical maturity with empirical knowledge” to increase their contribution to the international literature.[41]

In a recent roundtable discussion, Aydinli et al. discussed the possibility of homegrown theorizing while dealing with the following questions: “What is really stopping homegrown theories from moving into and becoming a respectable part of the core IR theory? What are the best ways of making homegrown theory relevant?” [42] The authors present certain reasons for the ‘lack’ of homegrown theorizing in Turkish IR scholarship. For instance, in his discussion, Aydinli claims that the Turkish IR discipline is young and immature since the first generation of IR scholars started theorizing in the 1980s; this generation started teaching IR theory in the 1990s, when Realism was the main theory in IR. He also claims that scholars do not cite Turkish articles, that there is a lack of prior intellectual background, a lack of theoretical discussion, and a limited understanding of theory among scholars in Turkish IR.[43] Other reasons for the lack of home-grown theorizing are also presented throughout the discussion, including the lack of expertise in research methods, limited willingness for scholarly self-reflection, and the ways in which IR theory is taught as part of the undergraduate IR curriculum. Interestingly, a recent survey made with Turkish IR scholars (TRIP Survey), showed that many scholars identify themselves as ’theoreticians’; however, very limited outcome is produced.[44]

Scholars did not only stop with the diagnosis of ‘the lack of homegrown theorizing’ but also offered prescriptions. They suggest that an initiative for homegrown theorizing in the periphery can start with a “healthy distance” towards or “dislike” of what is happening in the center. They add, however, that most scholars in Turkey, for instance, identify themselves as part of the Western academia.[45] As such, they are suffering ‘periphery’ problems and theoretical dependency, while at the same time identifying themselves with the center. Other prescriptions on the issue include establishing groups/conferences to bring periphery scholars together, making more use of local intellectual/historical backgrounds, developing more diversified ways of teaching IR theory, and working through mid-range theorizing instead of grand-theorizing.[46] Towards the end of the discussion Jörgensen claims that there is a need for a collective action on homegrown theorizing: “All such ideas have a limited chance of materializing into something close to a collective enterprise if we do not have three things: organization, organization and organization.”[47]

As a result of the need for improving the theoretical contributions made by Turkish IR scholars, an important discussion about homegrown theorizing has emerged in the last 15 years. Scholars have discussed whether ‘homegrown’ necessarily means a complete break with the 'core', or to what extent it must be completely ‘original’, ‘non-core’, ‘post-Western’ or ‘non-Western’. Indeed, maybe more importantly, there is no consensus among scholars on how to achieve home-grown theorizing, nor do they agree on the need for it to begin with. This discussion has been going on for a while. [48] This lack of consensus may also have caused an impasse as there are scholars who basically reject the core/non-core dichotomy. I argue that, to overcome this ‘impasse’ and the continued under-development of the IR discipline in Turkey, one needs to go beyond diagnosis and prescription and start directly with initiatives aiming at actual treatment. As most scholars taking part in the debate would agree to a certain degree, Turkish IR still needs to improve its ‘capacity’ to theorize. This capacity cannot be built in a day, but it is built over time, through accumulation of knowledge and ‘know-how’. I suggest that we may have already used much time in the diagnosis and prescription phase and overlooked further aspects of the treatment.

To this end, Aydinli and Biltekin offer another prescription similar to (but not the same as) what I present in the following section.[49] In their recent study on IR discipline in Turkey, the authors observe an expansion on the number of IR publications of scholars based in Turkey. Yet, they argue, there is limited disciplinary ‘sense of identity’ and ‘accumulation of knowledge’. This limitation, according to the authors, is the result of the lack of methodological diversity. They argue that the ‘predominantly qualitative’ nature of Turkish IR impedes debate, thereby hindering accumulation of knowledge. They suggest that increasing the use of quantitative methods may be a solution to the ‘fragmented’ IR community in Turkey. According to the authors, the use of quantitative methods and data collection would bring empirical, social, and methodological contributions to the IR discipline in Turkey as it would require scholars to “better define concepts”, establish “long-term research programs” based on data generation, and to overcome “selection bias more systematically.”[50] Through examples from different groups of literature, the authors show how certain studies were able to ‘talk to each other’ due to their clarity in terms of the methods, concepts, and approaches they use. The authors conclude with the prescription that research based on long-term and Large-N data collection and a quantitative approach may “help Turkish IR build the foundations upon which synchronized theoretical and methodological development can be based.”[51] Towards the end, the authors present their point through a short discussion on the dichotomy between “critical theory” and “quantitative methodologies.” They argue that Turkish IR did not yet give a ‘proper’ chance to the use of quantitative methods and that it would be “unfortunate” and “preemptive” to start with criticisms of these methods that were not yet “given a chance to be used, challenged, and revised.”[52]

I agree with Biltekin and Aydinli’s findings since the findings that I show in the following section indicate similar results. Yet I do not fully agree with their prescription. The authors seem to be equating “qualitative” with everything that is “not quantitative.” Indeed, what Turkish IR needs is not only more quantitative methods but instead more methods in general. I would argue that conceptual and methodological clarity are not exclusive qualities of quantitative methods but instead these qualities are at the essence of all methodological approaches.

Recently, All Azimuth Journal published a special issue dealing with the use of different methodological approaches by scholars in Turkey.[53] The special issue aimed at encouraging IR students and scholars in producing academic output based on high quality research. In his introduction to the issue, Aydinli observes that the discipline of IR in Turkey “has failed to appreciate the importance of methodology.”[54] So, following Aydinli, since research methods is the way scholars communicate and distribute scientific knowledge, we should start with ‘research methods’ training, rather than establishing new (or deepening the existing) fault lines between “quantitative vs qualitative” or “critical vs mainstream.” Therefore, I would argue, while also taking note of the increasing number of Turkish-language education programs across the country, Turkish scholars have more urgent problems and needs that revolve around methodological training. I offer the initiatives in the following section as necessary steps to contribute to the solution.

4. From Prescription to Treatment: Methodological Training in Practice

The above-mentioned self-reflections indicate that the IR discipline in Turkey did not fully acknowledge the importance of research methods in general. As Aydinli and Biltekin rightfully argue, studies using quantitative approaches are scarce. Yet, I argue, this should not imply that studies with qualitative methods are abundant in Turkey.

To start with an example, I collected data on studies published in Turkey, indexed in the Turkish scholarly index ULAKBIM, and that utilized the “securitization theory.” [55] I choose this theory for three purposes: 1) it is as ‘critical’ as most Turkish IR scholars studying security usually get, 2) it is mainly based on qualitative research since most studies that apply this theory do not use quantitative methods, and 3) each year approximately 4 articles get published using the securitization theory. I argue that the popularity of this theory among Turkish scholars comes from its relatively ‘easy-to-apply’ nature. When the international literature on securitization is checked, one might see that scholars who offered this theory have usually applied it to a case. So, the theory has been developed through various empirical case studies. The theory also has conceptual and methodological clarity and a step-by-step argumentation. For instance, securitization theory argues that certain issues in the social or political realm may be carried to the national security agenda by state elites, which turns those issues into threats. This is done by the discourse of policymakers and with the practices of the security professionals in the field. So, the steps are clear: 1) find an issue, 2) analyze and show the state elites’ ‘securitization’ discourse, 3) observe if it is accepted by the audience (public) as a security issue, and 4) analyze the findings. So far, the theory has been applied to many cases.

After collecting the articles published in Turkey, I asked the following question: “Does the study have a case, and if so, how does the author apply the theory?” I aimed at finding the methods that scholars have been using. Figure 1 summarizes part of the findings.

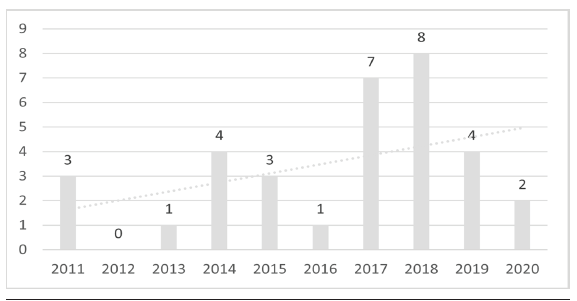

Figure 1: Turkish securitization studies by year[56]

As the figure indicates, approximately four articles a year are published on securitization. The following figure shows the research questions and arguments in these studies.

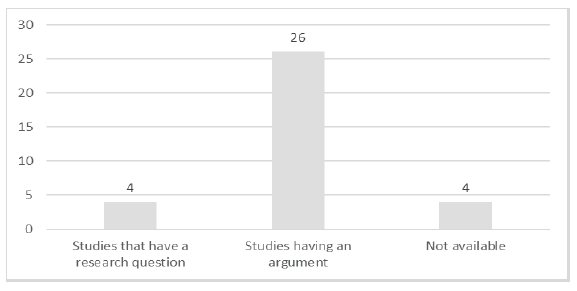

Figure 2: Turkish securitization studies: research question and argument[57]

As the figure illustrates, 26 out of 34 articles have an argument. The following figure illustrates the methodological approach used by these studies.

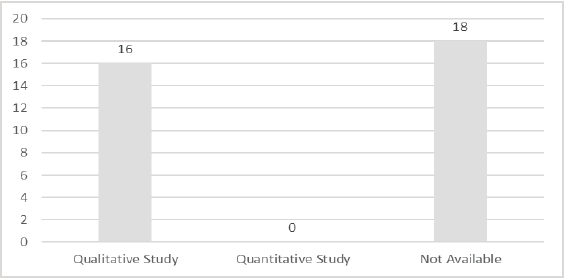

Figure 3: Turkish securitization studies: methodological approach

As the figure illustrates, more than half of those studies do not specify any methodological approach. There are no quantitative studies, but 16 studies use a ‘qualitative’ approach. I took one more step and asked, “which research method does the study take in its ‘qualitative’ approach?” The result is shown in the following figure.

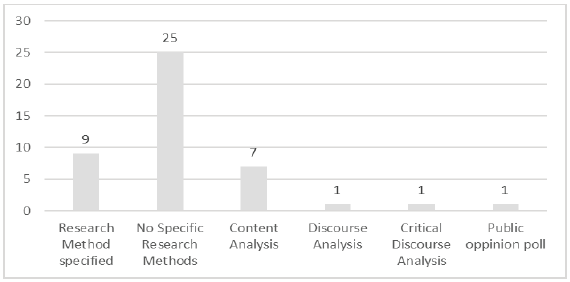

Figure 4: Turkish securitization studies: use of methods[58]

When Figure 3 and Figure 4 are analyzed together, it shows that only half of those ‘qualitative approaches’ clearly refer to a specific method. In total, 25 out of 34 studies on securitization theory published in Turkey are not clear on which methods they used to ‘apply’ the theory to a case. The data that I collected shows that most studies on securitization lack “methodological clarity” even if they talk about which methodological approach they take.

Here, I would make an important distinction between the meta-theoretical term ‘methodology’ and the use of ‘research methods’. Methods are techniques for gathering and analyzing evidence, data, or proof from the empirical world; whereas methodology is “a concern with the logical structure and procedure of scientific enquiry.”[59] Methodology deals more with how to establish the relationship between ontology (reality/existence) and epistemology (knowledge). Here, methodology deals with the ways in which knowledge of the things we see in reality can be collected. In general, one methodological question would be ‘How can we get or produce scientific knowledge of reality?’ Hence, objectivist vs. interpretivist, or qualitative and quantitative approaches are methodological approaches. Here, I would argue ‘qualitative’ research does not imply ‘methods free’ research or an ‘anything goes’ approach. Each methodological approach directs the researcher to different ‘research methods’, that is, the tools the scholar uses to collect evidence/data/proof (or whatever one prefers to call it). Conversely, specifying the methodological approach does not directly result in methodological clarity when the author is not clear on the steps he/she used to collect proof on his/her theoretical argument.

Labeling an approach as ‘quantitative’ or ‘qualitative’ does not bring methodological clarity. We should look for more than these labels. As the figures on the use of ‘securitization theory’ in the Turkish literature illustrate, studies that refer to a methodological approach as ‘qualitative or quantitative’ are not clear on which research method is used to support the theoretical arguments. Therefore, combining these observations with the self-reflection of Turkish IR scholars discussed above, I would suggest that the actual shortcoming here is not the lack of theoretical studies or ‘quantitative methodology’ but instead it is any IR study’s inability to establish these three connections: (1) metatheory and theory, (2) theory and the empirical application, and (3) methodology and methods. These three connections are of key importance to bring methodological clarity to a research study. First, every theoretical approach has metatheoretical assumptions that determine its ontological (what to study), epistemological (what kind of knowledge to produce), and methodological (how to study) stance. While thinking about the metatheoretical assumptions behind a theoretical approach, the scholar is also directed to think about how to establish the connection between theory and the empirical case to which the theory is applied. This opens a way for the second connection between theory and case, and the third connection between methodological approach and methods. Once the scholar decides on the metatheoretical stance, she/he then starts to think about how to connect the theory with the case. The scholar needs to decide on her/his methodological approach to connect the theory and the case because doing so determines the ‘research method’ that is used to collect evidence from the social world that supports theoretical claims. Here, methodology training enabling IR students to establish these three connections would serve the establishment of a scholarly community capable of producing replicable research, homegrown theorizing, and more significantly contributing to the ‘center/core.’ So, rather than stopping at diagnosis and prescription, we may continue with an attempt for further treatment. Like Aydinli and Biltekin, I argue that “data-collection” can be a good starting point, and I add that it does not have to be ‘quantitative’.[60]

Be it ‘quantitative’, ‘qualitative’, or ‘mixed’[61], data collection is a good start towards ‘treatment’ for several reasons. First, data collection is a long learn-in-action process, and before starting it requires the researcher to think carefully about and clarify the three main phases of academic research: (1) planning, (2) implementation, and (3) analysis. The planning phase is where the researcher chooses a topic, then a research question/problem, a proposed answer/hypothesis/argument/solution, and reviews the literature. The implementation phase is where the researcher collects data/proof/evidence/information to see if his answer/hypothesis/ argument/solution has a solid ground in the empirical world and shows the results. The analysis phase is where the researcher assesses the results, discusses the validity of her/his arguments, and evaluates further implications of the findings. Any research based on scrutinous data-collection inevitably leads the scholar to clarify how methods choices are made in the process. This is more so in studies based on data than it is in studies based on application of theories to specific cases. As the studies analyzed above indicate, theory applications that are not based on data-collection often fall into methodological ambiguity, since methodological clarity may not usually be the first thing that authors or their audience expect from those types of studies. However, in data-based studies, the logic is rather simple: a researcher cannot talk about or evaluate ‘data’ without clarifying how and where she/he collected it. At least, it is going to be one of the very first things the author and their audience would look for. The methodological clarity required by data collection makes the research replicable, enabling other scholars to test the validity of the claims made by the scholar (lingua franca).[62] Last but not the least, data-collection pushes the researcher to think about the three types of connections that I explained in the previous paragraph. At different phases of data-collection, the researcher must answer: What is my metatheoretical stance and methodological approach? 2) Which theory am I using (what is my argument/why am I collecting data)? and 3) How do I prove that my theory/argument holds and has solid ground in the empirical world (does my data prove the arguments I made)?

As part of this treatment in IR in Turkey, I offer an initiative and two exemplary projects that may help to develop data-collection and methodology training: 1) the Social Sciences Data Repository, 2) the Global risks Assessment Dataset (GRAD) and Global Security Database (GloSec) projects. First, the Social Sciences Data Repository at the Global Studies Platform[63] is an initiative aiming to serve as a repository for datasets produced in Turkish, or by scholars in Turkey who conduct international studies. The repository is born out of two necessities: 1) there is no such repository for studies in Turkey, and 2) there is no such precedent in the IR discipline in Turkey. If a scholar produces a dataset in Turkish, he/she either puts limited parts of it in the articles or rarely uploads it to a specific website. There is only one IR journal in the SSCI-index that occasionally publishes Turkish IR articles and that journal has recently decided to use the Harvard Dataverse.[64] Many other journals that publish IR articles in Turkey (either in English or Turkish) still do not use any platforms. The data repository currently targets journals that are producing Turkish articles based on datasets in IR.

Data-collection and sharing have only very recently started developing in Turkish IR. Yet, there is an increasing tendency among new generations of Turkish IR scholars, or IR scholars based in Turkey, to learn and apply various data collection methods. The data repository may serve as an alternative for this group of scholars and prospective studies published in Turkish. By uploading their data onto the Social Sciences Data Repository, researchers will be able to share and update different versions of datasets and codebooks, label their data under their name by getting Digital Object Identifier (Doi) numbers, and get a citation linked to their datasets. The aim here is to disseminate data-based research and enable data-sharing among Turkish scholars, thereby helping the accumulation of IR knowledge.

In addition to data-sharing and accumulation of knowledge, I offer that Turkish IR scholars interested in this type of research may benefit from designing ‘Social Science/International Studies Research Labs’ with graduate students to produce data-collection projects and train new generations of graduate students that can produce research outputs based on clear, replicable, and rigorous research designs, in Turkey. This sort of “learn-in action” collaborations will give graduate students in Turkish universities the ability to have a global scholarly outreach and communicate to the global scholarly community. Like some of the studies mentioned above, I believe that rigorous methodological training is key to contributing to Global IR scholarship, and should start early at graduate school. To clarify this suggestion, I present two recent initiatives: GRAD and GloSec. The Global Risks Dataset (GRAD) is a learn-in-action research project that has two specific aims: (1) Train graduate students and early-career academics on the basics of data-collection in international relations (2) Collect a comprehensive dataset for tracking down the evolution of risks and challenges against humanity since the end of the Cold War Era. The project is designed in a step-by-step structure, where each step has multiple academic outputs to help the career development of the participants.[65]

GRAD is based on data collected from various sources on the evolving nature of global threats. The dataset currently contains our findings on a qualitative assessment of risks in the reports of several international institutions.[66] Currently, we have listed references to different types of risks under certain issue areas such as poverty/hunger, development/economy, health, nuclear power, technology, and the environment. The dataset contains detailed answers to the following main question: “How did ‘global threat perception’ change since the end of the Cold War and what are the causes and probable consequences of that change?” While qualitatively assessing and analyzing the reports in detail, we also quantitatively code “number of references to threats” and then establish scales on the ‘intensity’ and ‘urgency’ of these threats. We thereby find patterns of the change of these threats and their probable future direction. At the end, beside scholarly publications we will also come up with concrete policy recommendations by stressing the intensity and urgency of threats under different issue areas. Initially, the reports that we code start from immediate post-cold war (1990s) coming until now (2002). The dataset is based on our initial observation and argument that, there are catastrophic risks at a global scale that researchers have been warning the world about for decades. The world could have been, and can still be, prepared for those global risks especially when supporting data is made publicly available.

The dataset building process has pedagogical contributions as well. Through establishing a ‘research lab’ on international studies, I keep my graduate students actively involved in researching topics in their field. We also discuss the potential of writing their theses and dissertations out of their roles in the project. This type of teamwork-building activities offers the opportunity to transfer methodological skills to students. Pedagogically, I am afforded to the privilege of training prospective/early-career scholars on data-collection, research/project design, proposal writing, as well as other academic activities such as conference applications and participation, teambuilding exercises, among other things. One might assume that these skills are transferred at most graduate programs in universities, but the scholarly output and the dissatisfaction in the self-reflections summarized above indicate that the Turkish IR discipline is in dire need of more research methods instruction and, concomitantly, train-in-action data-collection projects. Indeed, the research topics that this type of work is applied might vary, yet the mechanism, or the craft of research would be standardized and transferable to various other research topics as well.

GloSec, meanwhile, is aiming to become a database for the security conceptions of aşş countries in the world. Currently, the research focuses on collecting data on Turkey’s security perceptions (Turkey’s security dataset-TurSec) with an aim to develop new datasets on other countries of the world.[67] As part of the Turkey data we analyze Turkey’s threat perception concerning the post-Arab-uprisings MENA region. We analyzed the speeches of Turkey’s policymakers and the reports of Turkish National Security Council. We are quantitatively coding the following: number of references to a specific threat, the type of threat, cause of the threat, and the source country.[68] Currently, the project relies on the hand-coding of the materials we found.In addition to data-collection the , research team regularly meets for online-lectures on several topics such as designing data collection, finding raw data, material selection/sampling, the advantages and limitations of quantitative and qualitative approaches, the advantages and limitations of hand-coding and computer-assisted coding, and other alternative approaches, all of which turn grant the project a “methods school” quality. This is not just a data-collection project but part of a combination of efforts conducted under the Global Studies Platform, that aims to deliver research methods training online to graduate students in Turkey. The data repository will also serve as the home for both GloSec and GRAD datasets and their bilingual (English and Turkish) codebooks will be prepared with step-by-step guidelines on data-collection to serve as examples to encourage new generations of scholars in Turkey conducting data-based research.

5. Conclusion

The Global IR discussion seems to be a new ‘great disciplinary debate of IR’ in the making. Until now, it has mainly revolved around the discussion on developing a more inclusionary approach in the ways of doing IR research and on the appreciation of the knowledge produced in the non-core contexts. Following the All-Azimuth Workshop theme, this article suggests that an important step in having ‘global IR’ is ‘self-reflection’ in the ‘non-core’. However, in suggesting that, I would refrain from building a dichotomous approach that creates boundaries which separate ‘local’ scientific knowledge from the ‘global’. Instead, I would argue that there is a global ‘knowledge’ pool where the products of disciplinary communities with different local settings accumulate. While the product –scientific knowledge– itself accumulates in a global pool, the way that it is produced is highly influenced by local settings. These ‘local’ settings determine how knowledge is produced, what kind of knowledge is produced, and to what extent the end-product is brought into the ‘global’ pool. Therefore, while debating the way to achieve a more inclusionary and ‘truly global IR’, one needs to appreciate the local settings as well.

If ‘global IR’ turns into one of the so-called ‘great disciplinary debates’ in the future, I suggest that there is so much that the study of these local settings, or let us say the study of local contexts, can bring to the debate. Indeed, I would argue that the potential for ‘progress’ in globalizing IR, lies in the study of local disciplinary contexts more than it does in studies simply re-emphasizing the fact that the discipline is not ‘global’. Identifying such potential lies in the study of ‘self-reflections’ of scholars that produce knowledge in the local context. This article, therefore, took a first step in this direction.

While prescriptions differ from one study to the other, there appears to be a consensus on two general but interrelated shortcomings that the literature on IR in Turkey agree upon: (1) limited original, ‘home-grown’, or sui-generis theoretical contributions and (2) lack of methodological clarity. One can diagnose and think of many reasons behind these shortcomings including but not limited to: the local core/periphery relations, higher education regulations, institutional settings, the academic promotions system, incentives/disincentives of the promotion criteria, among other things. Some of these topics have already been discussed both in the literature and in academic conferences/workshops and there is probably more that can be identified through future research. I suggest, however, that the scholarly community needs to go beyond ‘diagnosis’ and do more to improve these conditions, at least by way of engaging in scholarly production.

With new generations of IR scholars entering the field, the state of the IR discipline in Turkey has become more developed compared to the 1990s and even 2000s. The IR disciplinary knowledge background in Turkey has matured enough to add more to the global IR knowledge pool. As the global IR debate flourishes in the international literature, this is an important time for IR scholars in Turkey to showcase original contributions. This article suggests that one of the initial steps in this direction may be to address the shortcomings directed by the IR scholars in Turkey. Therefore, following the path that is already offered in the literature, I submit that we start with addressing ‘methodological poverty.’ Since methodological clarity serves as a lingua franca[69] in academic communication, I argue that moving forward to address methodological poverty may contribute to the inclusion of IR knowledge ‘made in Turkey’ in the global knowledge pool.

I also argue that the shortcomings stated in the Turkish IR literature - limited theory development and the lack of methodological clarity- can be overcome by producing research that is based on data-collection. As the figures on the use of ‘securitization theory’ in the Turkish literature illustrate, even studies that refer to a methodological approach –qualitative or quantitative– are not clear on which research methods is used to support the theoretical arguments. This way of doing research results in ambiguity about how the theory is applied to the case at hand. I suggest that thinking and establishing three connections may help scholars overcome this ambiguity: (1) metatheory and theory (2) theory and empirical application, and (3) methodology and methods. I argue that these three connections would bring methodological clarity to studies aiming to develop theories or apply theories to specific cases. I offer that designing research projects based on ‘data-collection’ can serve as a treatment to methodological ambiguity. In research based on data-collection the logic is rather simple, a researcher cannot talk about or evaluate ‘data’ without clarifying how and where she/he collected it. At least, it is going to be one of the very first things the authors and their audience would look for which leads researchers to think about the three connections even before starting to collect data.

I aim to go beyond ‘diagnosis and prescription’ and offer exemplary projects to contribute to the IR discipline in Turkey in its path to overcome its shortcomings: the Social Sciences Data Repository, GRAD and GloSec. The open access data repository will serve as a platform to let Turkish scholars openly share the datasets they produce together with bilingual (both in Turkish and in English) codebooks describing the methodological steps they take in doing their research. In doing so the repository will open ways for accumulation of knowledge, data reproduction and theory development. Such a repository may turn into a reference point for new generations of scholars willing to do data-based research and share datasets with the scholarly community. In addition to the data repository, GRAD and GloSec constitute examples of research groups based on learn-in-action data-collection. Both projects aim at training prospective/early-career scholars in data-collection, research/project design, proposal writing, and taking part in various academic activities.

To sum up, significant efforts are being directed to knowledge production in the non-American, non-European or non-core IR communities. So far, as part of the globalizing IR debate, a considerable amount of research output has been produced calling the global IR community to give more credit to the contributions of the non-core. These studies are paving the way for progress in both the IR discipline across the globe and specific local disciplinary communities. If the debate evolves into a ‘great disciplinary debate’ it may also widen a ‘sectoral niche’ to be filled in with more knowledge produced in specific local IR communities. Hence, as the debate heightens in the global IR discipline, it is also a wonderful time for ‘self-reflection’ in the non-core IR communities. I would like to end the article by crying out a message: true globalization of IR can be achieved only through local quality ‘revolutions’, and the first phase -at least in the IR conducted in Turkey- would be methodological improvement.

Acharya, Amitav. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–15.

———. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives on and Beyond Asia. London: Routledge, 2010.

Aktürk, Şener. “Temporal Horizons in the Study of Turkish Politics: Prevalence of Non-Causal Description and Seemingly ‘Global Warming’ Type of Causality.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 117–33.

Anderl, Felix, and Antonia Witt. “Problematising the Global in Global IR.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 49, no. 1 (2020): 32–57.

Aydın-Düzgit, Senem, and Bahar Rumelili. “Discourse Analysis: Strengths and Shortcomings.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 285–305.

Aydinli, Ersel. “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (January 22, 2019): 109–15.

Aydinli, Ersel. “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-Reflections on Dialogue with the Core.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13, no. 2 (2020): 287–312.

Aydinli, Ersel, Erol Kurubaş, and Haluk Özdemir. Yöntem, kuram, komplo: Türk uluslararası ilişkiler disiplininde vizyon arayışları. Istanbul: Kure Yayınları, 2015.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 267–87.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 289–303.

———. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693–712.

———. “Turkey: Towards Homegrown Theorizing and Building a Disciplinary Community.” In International Relations Scholarship Around the World, edited by Arlene B. Tickner, 208–22. London: Routledge, 2009.

———. “Türkiye uluslararası ilişkiler disiplininde özgün kuram potansiyeli: Anadolu ekolünü oluşturmak mümkün mü?” Uluslararasi Iliskiler 5, no. 17 (2008): 161–87.

Aydinli, Ersel, Mustafa Aydın, Emre Baran, Andrey Makarychev, Karen Smith, Ramazan Gözen, Pınar İpek, et al. “Roundtable Discussion on Homegrown Theorizing.” All Azimuth 7, no. 2 (2018): 101–14.

Bezci, Egemen. “Secrecy and the Study of International History: Missing Dimension in Turkish Foreign Policy.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 327–38.

Bilgin, Pinar. “‘Contrapuntal Reading’ as a Method, an Ethos, and a Metaphor for Global IR.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 134–46.

———. “How to Remedy Eurocentrism in IR? A Complement and a Challenge for The Global Transformation.” International Theory 8, no. 3 (2016): 492–501.

———. “Looking for ‘the International’ beyond the West.” Third World Quarterly 31, no. 5 (2010): 817–28.

———. “The International Political ‘Sociology of a Not So International Discipline.’” International Political Sociology 3, no. 3 (2009): 338–42.

———. “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR?” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 5–23.

Fisunoğlu, Ali. “System Dynamics Modeling in International Relations.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 231–53.

Hatipoğlu, Emre, Osman Zeki Gökçe, İnanç Arın, and Yücel Saygın. “Automated Text Analysis and International Relations: The Introduction and Application of a Novel Technique for Twitter.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 183–204.

Hobson, John M. “Is Critical Theory Always for the White West and for Western Imperialism? Beyond Westphilian towards a Post-Racist Critical IR.” Review of International Studies 33, no. S1 (2007): 91–116.

———. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106 (2019): 41–60.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Jorgensen, Knud Erik. “Would 100 Global Workshops on Theory Building Make A Difference?” All Azimuth 7, no. 2 (2017): 41–58.

Kaliber, Alper. “Reflecting on the Reflectivist Approach to Qualitative Interviewing.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 339–57.

Köstem, Seçkin. “International Relations Theories and Turkish International Relations: Observations Based on a Book.” All Azimuth 4, no. 1 (2015): 59–66.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney. “Is International Relations a Global Discipline? Hegemony, Insularity, and Diversity in the Field.” Security Studies 27, no. 3 (2018): 448–84.

Özdamar, Özgür. “An Application of Expected Utility Modeling and Game Theory in IR: Assessment of International Bargaining on Iran’s Nuclear Program.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 205–30.

Palabıyık, Mustafa Serdar. “Broadening the Horizons of the ‘International’ by Historicizing It: Comparative Historical Analysis.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 307–25.

Palmer, Norman D. “The Study of International Relations in the United States: Perspectives of Half a Century.” International Studies Quarterly 24, no. 3 (1980): 343–63.

Şan-Akca, Belgin. “Large-N Analysis in the Study of Conflict.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 135–56.

Smith, Steve. “The Discipline of International Relations: Still an American Social Science?” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 2, no. 3 (2000): 374–402.

Strange, Susan. “1995 Presidential Address ISA as a Microcosm.” International Studies Quarterly 39, no. 3 (1995): 289.

Sula, İsmail Erkam. “An Eclectic Methodological Approach in Analyzing Foreign Policy: Turkey’s Foreign Policy Roles and Events Dataset (TFPRED).” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 255–83.

———. “Güvenlikleştirme kuramında ‘söz edim’ ve ‘pratikler’: Türkçe güvenlikleştirme yazınında ‘yöntem’ arayışı [‘Speech Acts’ and ‘Practices’ in Securitization Studies: A Search for ‘Methods’ in Turkish Securitization Literature].” Güvenlik Stratejileri Dergisi 17 (2021): 85-118.

Tickner, Arlene. “Seeing IR Differently: Notes from the Third World.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 32, no. 2 (2003): 295–324.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Waever, eds. International Relations Scholarship around the World. London: Routledge, 2009.

Travlos, Konstantinos. “Mobilization Follies in International Relations: A Multimethod Exploration of Why Some Decision Makers Fail to Avoid War When Public Mobilization as a Bargaining Tool Fails.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 359–85.

Ünver, H. Akın. “Computational International Relations What Can Programming, Coding and Internet Research Do for the Discipline?” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 157–82.

Vasilaki, Rosa. “Provincialising IR? Deadlocks and Prospects in Post-Western IR Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 41, no. 1 (2012): 3–22.

Waever, Ole. “The Sociology of a Not So International Discipline : American and European Developments in International Relations.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 687–727.

Yong-Soo, Eun. “Global IR through Dialogue.” The Pacific Review 32, no. 2 (2019): 131–49.