Fatih Bilal Gökpınar

Bursa Uludag University

Özgür Aktaş

Istanbul University

In this paper, we adopt Walter Carlsnaes’ tripartite approach in order to scrutinize the consistency of Türkiye’s climate policy with changing climate regimes. We explain the actor-structure duality in climate policy through the interaction of climate regimes and Türkiye's climate policy. The paper reveals the causality behind the policies implemented by Türkiye as a result of its core values and preferences, and explains their continuities. Finally, we address the potential of the European Green Deal to influence Türkiye's preferences, and herefore its climate policy.

The fight against climate change remains one of the main issues studied in world politics. The issue of climate change is strongly interconnected with many other areas; even different massive problems such as global justice, gender, and the COVID-19 pandemic are examined in conjunction with climate change.[i] Similar to other global challenges, the climate crisis is not an issue to be solved by isolated initiatives, but it requires comprehensive action supported by many actors. This characteristic of the problem brings the climate crisis to the center of international relations. Especially since the foundation of UNFCCC in 1992, climate politics has been a crucial part of foreign policy agendas. As nation-states preserve their status of being primary actors in world politics, foreign policy analysis (FPA) is a key tool to understand and explain the deadlock in global problems. However, there are plenty of approaches of FPA that prioritize different ontologies and causalities to expound why nation-states act in some particular ways but not in others. So, the question still remains, what is the most convenient approach to analyze foreign policy action within the context of global issues?

Numerous approaches of FPA could be categorized in many different ways according to their epistemological and ontological premises.[ii] However, the main determinant in this literature is the agent-structure problematique. No matter how it is named (domestic & international politics, innenpolitik & aussenpolitik, internal factors & systemic incentives, holism & individualism, etc.), the approaches of FPA are always shaped by the tension between agent-based and structure-based positions. Here, a third way is to focus on the interplay between agent and structure to examine how these two ontologies generate causalities to transform each other.[iii] In the case of global climate politics, the two main factors to analyze are the structure of the climate regimes[iv] and the actions of nation-states. These two elements have been constructing each other especially since the 1990s, thus the foreign policy actions concerning climate politics could not be pictured via solely agent-based or structure-based explanations.

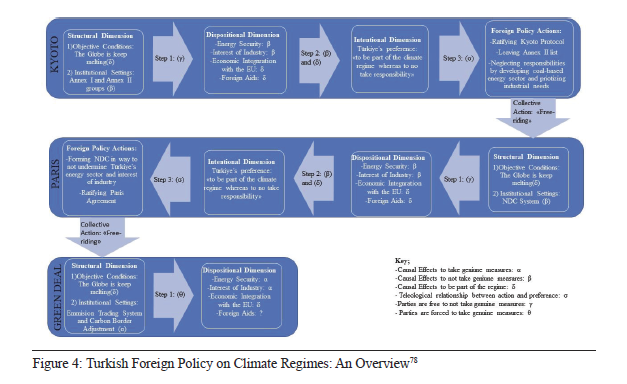

In this paper, we aim to examine Turkish foreign policy on climate regimes via Carlsnaes’ tripartite approach to explain Türkiye’s lack of cooperation in fighting against climate change. Since the 1990s, Türkiye’s foreign policy objectives and tendencies have drastically changed several times, yet its climate policy of not taking genuine responsibility for climate change has firmly endured. Arguably, throughout the foundation of the Republic, this foreign policy behavior of Türkiye might be the most consistent one, and we claim that with the European Green Deal, this consistency in foreign policy will potentially change. Thus, by focusing on the interplay between agents and structure, we intend to explain the reasons generating the consistency and promising change via applying Carlsnaes’ tripartite approach. In accordance with our purposes, the paper is structured in three parts. First, Carlsnaes’ approach will be introduced, and how the approach is going to be adopted will be explained. Second, the Kyoto Protocol and Türkiye’s foreign policy actions will be examined in four steps. This part will be followed by an examination of the Paris Agreement and Türkiye’s foreign policy actions in the same four steps as the second part. Third, the European Green Deal’s potential to change the structural conditions for Türkiye will be discussed. In the concluding part, the potential change of TFP in climate regimes will be speculated on.

In this paper, we will adopt Walter Carlsnaes’ tripartite approach to scrutinize the consistency of Turkish foreign policy (TFP) on climate regimes. There is a genuine connection between the tripartite approach’s ideational background and its tools that are designed to elucidate foreign policy. Thus, to introduce this approach, it is crucial to track the theoretical debates that enabled this particular way of understanding and explaining foreign policy actions. There are three constituents of the ideational background of the tripartite approach. First, in accordance with the fourth great debate of International Relations[v] (IR), scholars tended to address debates regarding the discipline by focusing on meta-theoretical discussions after the mid-1980s. While the theories and approaches of IR have been sharply divided into categories such as understanding/explaining, rationalist/reflectivist, and positivist/post-positivist based on their meta-theoretical premises,[vi] long-time meta-theoretical problematiques such as level of analysis and agent-structure issues were also put on the table.[vii] Carlsnaes did not remain unconcerned about the meta-theoretical discussions that had been conducted by scholars of IR theory. He intended to examine the meta-theoretical issues in order to pinpoint some of the implications for foreign policy analysis.[viii]

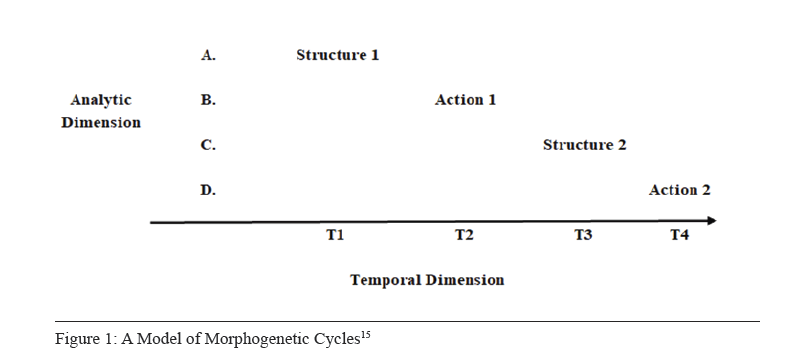

Second, in accordance with the first constituent, Carlsnaes adapted the critical realist approach, specifically Margaret Archer’s morphogenetic framework, as his position on the agent-structure problem. While the critical realist scholarship provided the meta-theoretical background for analyzing the reciprocal interaction of agents and structure, Archer’s morphogenetic framework particularly contributes to Carlsnaes’ approach by adding a temporal perspective. A general critical realist perspective to the agent-structure problem is embodied by the idea that agents and structures ontologically exist and that they generate causalities for the conditions of existence of each other.[ix] In addition to this, Archer’s morphogenetic framework introduces that structure and agency are analytically separable and temporally sequenced.[x]

Last but not least, it is crucial to understand the connection between the tripartite approach and the transformation that FPA underwent. Since the end of the Cold War, FPA as a sub-field has attracted notable attention. The new dynamics of world politics undermined ‘arcane’ systemic explanations and indicated the need for a change in perspective. This caused a proliferation of models and approaches of FPA. Besides, the so-called ‘cognitive revolution’—a commentary on the limits of rationality based on the development of the discipline of psychology—had a remarkable influence on the studies of IR and FPA.[xi] Accordingly, the psychological and cognitive approaches lend impetus to studies of FPA. In this environment of the proliferation of approaches to FPA, Carlsnaes aimed to propose a ‘flexible’ approach that would involve different perspectives to analyze foreign policy. It is also flexible since it allows the practitioners to focus on certain relations and causalities while giving subsidiary attention or neglecting others.[xii]

These constituents of the ideational background were critically influential on the formation of the approach, and they distinctly shaped the main features of it.

iii. He claims that as long as the foreign policy approach characteristically fits into one of the cells of the matrix, it is ipso facto problematic.[xiv] He points out that these approaches indispensably privilege some causalities over others due to the meta-theoretical commitments. Thus, a persuasive FPA approach should be embodied in several approaches.

Figure 1: A Model of Morphogenetic Cycles[xv]

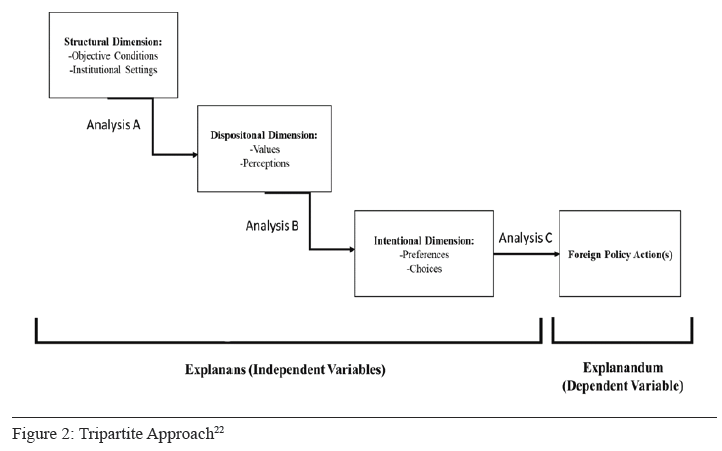

The tripartite approach could be divided into two main parts: namely, dependent and independent variables, or as Carlsnaes typically uses, explanandum and explanans. While explanandum signifies foreign policy action, explanans consists of three aspects: intentional, dispositional, and structural dimensions.[xvi] This approach embodies three dimensions of explanations (see Figure 2). First, there is a teleological relationship between foreign policy actions and the intentional dimension. The intentional dimension includes two conceptual categories: preferences and choices. This explanation (arrow c in Figure 2) evinces the specific reasons for or goals of a certain policy. As Carlsnaes specifies, this is a necessary step by reason of the intentional nature of the explanandum. The analysis between intentional dimension and foreign policy action would only unearth the reasoning behind a particular action. Although this analysis might be adequate to understand the connection between actions and intentions, it will be deficient to illuminate why the actor is driven to have certain intentions. To comprehend this, an analysis between intentional and dispositional dimensions (arrow b in Figure 2) is required. The dispositional dimension embraces two conceptual categories: values and perceptions. In this analysis, it is intended to address the perceptions and underlying values which drive the actors to pursue certain goals. This is the analysis that cognitive and psychological approaches might enter into the study.[xvii] In order to strengthen the study by scrutinizing structural causalities, a third analysis is needed between structural and dispositional dimensions (arrow a in Figure 2) to examine how structural factors constrain and enable the actor’s behaviors. The structural dimension consists of objective conditions and institutional settings. Unlike the first analysis, in the second and third, there are causal relations between dimensions.

Despite its theoretical strengths, the tripartite approach also has shortcomings regarding its explanatory capacity and applicability. Concerning the approach, two main issues are relevant to this study. First, at the second step of the analysis, Carlsnaes’ explanations for his approach mostly focus on clarifying a cognitive analysis that addresses individuals as a scientific object.[xviii] Therefore, his account lacks detailed instructions for foreign policy analyses that take nation-states as the unit of analysis. Second, as Carlsnaes states, his framework is proposed to explain single-policy actions. Thus, it is not suitable for analyzing a series of actions over time. To examine a series of actions, he suggests considering the outcomes of the policy undertakings, however, he does not introduce a structured model.[xix] By proposing to connect the foreign policy action and the structure, he stresses that the actions are capable of affecting structures and actors.[xx] What he does unsatisfactorily is formulating the foreign policy action of the nation-state as if it has the capacity to alter structures. However, from the critical realist perspective, even though the actions are capable of changing the structures, since the social structures are enduring, one particular action would hardly alter the structure.[xxi]

Figure 2: Tripartite Approach[xxii]

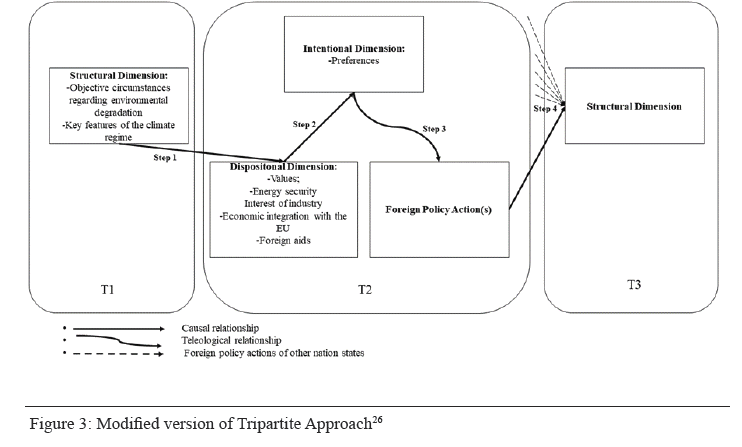

In light of the ideational background and the substances and shortcomings of Carlsnaes’ aforementioned approach, the present study offers a particular way of employing the tripartite framework to enhance its explanatory power for scrutinizing the consistency of Turkish foreign policy on climate regimes. For our study, three structures are considered to be relevant to the analysis, meaning that the analysis could be separated into three temporal dimensions. These can be referred to as the Kyoto regime, the Paris regime, and the European Green Deal.

All three dimensions of the tripartite model consist of two conceptual categories to allow practitioners to make an exhaustive analysis. Nevertheless, in this study, we aim to utilize four of these conceptual categories. While it is intended to examine the objective circumstances regarding environmental degradation in the objective condition, in institutional settings, the key features of the climate regime will be analyzed. The relations between these two factors of structural dimension are reciprocal, thus they are viewed as both mutually dependent and analytically distinct.[xxiii] In the first step, how Türkiye, as the actor, is disposed toward the causalities of the structural dimension will be scrutinized. This analysis will lead us to a dispositional dimension, where the values that might coincide and collide in driving the actor to different preferences. In this study, we intend to examine Türkiye’s dispositional dimension by referring to four values. These are: i) energy industry, ii) interest of industry, iii) economic integration with the EU, and iv) climate funds. In the second step, how these four values drive Türkiye to have particular preferences will be examined. This analysis will be followed by the third step, in which the teleological link between the preferences and the actions of the actor is pointed out. Unlike the other steps, in which a causal relationship between dimensions is analyzed, due to its teleological nature, this step will be purely descriptive.[xxiv]

In order to address the shortcomings of the tripartite approach, two solutions will be suggested for our analyses. First, we found it useful to adapt Kuniko P. Ashizawa’s state-centered method for the second step of the tripartite approach[xxv] contrary to Carlsnaes’ version. Instead of a cognitive-based method that focuses on individuals, Ashizawa introduces “value-processing,” meaning that a state-centric analysis could be held by defining states’ coinciding and colliding values for some cases. Influenced by structural causalities, while some of these values might be highly effective in driving the actor towards a particular intention, others might be relatively less effective. A different structure is capable of changing which values will be most influential in determining the decision-making process. Second, to explain the connection between three temporal dimensions, an additional step to tripartite analysis will be added. Yet, the foreign policy action of one nation-state obviously would not be able to alter the structure. Thus, in this additional analysis, we will examine the character of Türkiye’s action by giving references to its preferences (intentional dimension) and explaining how the collective actions of nation-states that are driven by the same preferences generated a new structure.

Figure 3: Modified version of Tripartite Approach[xxvi]

3.1 Kyoto regime analysis, step 1: from structural dimension to dispositional dimension

In the preparation of the Kyoto Protocol, and previously in the establishment of the UNFCCC, the impact of the objective conditions at that time was highly influential. In the IPCC First Assessment Report, published in 1990, it was revealed that the cause of global warming is undoubtedly human activities and that CO2 is responsible for more than half of the greenhouse-gas effect. In addition, it has been announced that under a “business as usual” scenario, the planet would continue to warm by 0.3 degrees Celsius per decade.[xxvii] The conclusion derived from this report is that global warming would affect life in a relatively short time period, and that the earth would not support the current form of habitats if new policy actions are not undertaken.

The Kyoto Protocol was the first agreement in which states agreed, with binding targets, to reduce global emissions in order to prevent global warming. The establishment of the UNFCCC in 1992 was the first step towards the creation of the Kyoto regime. Along with the UNFCCC, based on scientific evidence, states have accepted global warming as a threat caused by humanity and have agreed to work together to solve it. The Kyoto Protocol was accepted at the 3rd Conference of Parties (CoP) in 1997. With this agreement, a collective target was set to reduce greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. (Kyoto Protocol, Article 2).

The central claim of the Kyoto Protocol, which stems from the principle of the UNFCCC, is that although all countries have a share in carbon emissions, the share of early industrialized and developed countries is many times higher, so the responsibilities that such countries must undertake are different from those of other countries. Accordingly, the key feature of the Kyoto Protocol is the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities.’ This principle puts the responsibility of reducing carbon emissions on the shoulders of developed countries.[xxviii]

The responsibilities that countries have to undertake are basically divided into three different groups according to the classification made under the umbrella of the UNFCCC in 1992. The first of these groups is Annex I. Annex I covers OECD countries, EU countries, and countries undergoing the transition process to a market economy. According to the Kyoto Protocol, the countries responsible for making emission reductions are Annex I members.[xxix] The second group created under the UNFCCC is Annex II. This group includes OECD countries, namely Annex I countries except for the transition countries. In addition to the responsibilities given to them in Annex I, countries in this group are required to provide financial and technological support to enable developing countries to undertake emissions reduction activities under the Convention and help them adapt to the adverse effects of climate change.[xxx] Countries outside these groups are categorized as non-Annex I countries. The non-Annex I group consists of developing countries. No binding emissions reduction responsibility has been imposed on these countries by the Kyoto Protocol. To sum up, the structural dimension of the Kyoto Protocol strongly encouraged developing states to be part of the Protocol. However, in this framework, those states had the opportunity to take no responsibility since there were no binding conditions to take genuine climate measures.

3.2. Kyoto regime analysis, step 2: from dispositional dimension to intentional dimension

Türkiye's initial value was to maintain its energy supply, which should be compatible with its growing population and developing economy. In other words, since Türkiye has scarce resources in terms of natural resource reserves, it has prioritized energy security in its economic model and continues to do so when assessing future developments. Therefore, Türkiye's energy security sensitivity was so dominant that it would affect climate policies as well as energy policies. In order to ensure energy security and reduce its dependence on energy imports, Türkiye aimed to exploit domestic coal resources more, thus alleviating the energy security problem. Accordingly, between 1990 and 2009, Türkiye doubled its energy-based carbon emission rate.[xxxi] In the First National Communication on climate change published in 2007, Türkiye underlined that the optimum use of domestic resources such as coal and hydraulics is extremely important to create a reliable energy supply. It was officially emphasized that coal had an indispensable place in Türkiye's energy map.[xxxii] The National communication that came after this year continued to underline that coal is vital to protect the energy security required by Türkiye's developing economy and growing population. It was also emphasized that Türkiye would not have enough energy without coal. In 2012, the aim was to promote domestic energy in order to reduce dependence on oil and natural gas, so 2012 was declared the Year of Coal, and a series of incentives were announced for coal investments. This has meant that Türkiye would adopt a high-carbon economic model to ensure energy security. Aiming to develop a coal-based energy sector and diversify the energy supply to ensure energy security, Türkiye was also importing coal from abroad to a large extent, depending on its energy needs.[xxxiii] This stance ignored Türkiye's contribution to the global fight against climate change and has thus made a climate policy that ensures that greenhouse gas reduction is impossible.[xxxiv] To sum up, Türkiye’s perspective on energy security was one of the key factors preventing genuine measures to fight against climate change, since they were inherently in conflict.

Another value of Türkiye was to protect the interests of its industry. By the 2000s, Türkiye's primary goal was to increase its production capacity and develop its industry.[xxxv] Türkiye has built sectors such as construction, domestic transportation, textiles, and real estate services, especially after 2003, on the path of rapid economic growth.[xxxvi] Therefore, Türkiye, especially in construction and textiles, has turned to a high-carbon, low-tech developmentalist path for its economic growth, as Ümit Şahin has said.[xxxvii] Economic studies show that economic growth between 2003 and 2009 became more energy- and pollution-intensive than the 1995-2002 period, and high-carbon economic activities related to construction, such as real estate and transportation, were among the leading sectors.[xxxviii] Although the share of energy used by the iron-steel and cement sectors in the manufacturing industry decreased from 36.9% in 1990 to 23% in 2003, it increased rapidly starting in 2008 to 45.3% at the end of 2014.[xxxix] By declaring that “environmental policies should not harm development,”[xl] Ministry of Development has made a clear implicit hint that Türkiye would not adopt a climate policy that would hinder Türkiye's path in economic development.

Another value determining Türkiye's climate policy was to improve its economic integration with the EU. Since the late 1990s, Türkiye has taken significant steps towards becoming an EU member and revised its institutional framework with regulations in this direction. However, Türkiye's priority in integration with the EU was to advance economic integration between the parties. All the chances of establishing a partnership with the EU, Türkiye's largest export and import partner, were being evaluated. Climate negotiations were also seen as an opportunity for Turkey to improve relations with the EU. Although one of the reasons for Türkiye’s inclusion in the climate change negotiations was to get closer to the EU, on the other hand, Türkiye did not want to take a responsibility that would harm its economic relations. In short, one of the values determining Türkiye's climate policy was to increase integration with the EU, but in a way that would not harm its economic development.

The fourth value of Türkiye was access to climate funds. As it was stated in many official documents, Türkiye intended to conduct its fight against climate change via financial sources provided by other actors. Therefore, Türkiye's ability to access non-Annex funds was one of the main factors that would enable it to take adequate steps as a party to the Kyoto Protocol. Nevertheless, as an Annex II country, Türkiye could not receive these resources, and moreover, it was also obliged to support underdeveloped countries. Even though it was crystal clear that Türkiye was not able to benefit from climate funds due to its status in the UNFCCC, in almost every official report and document, Türkiye repeated that accessing the climate funds was vital for developing an effective climate policy. Türkiye underlined that climate funds were an indispensable part of its climate policy.[xli] Thus, the motivation for acquiring more climate funds should not be neglected when considering Türkiye’s involvement in the Kyoto Protocol.

While Türkiye’s concerns for energy security and preserving the interest of industry were strong motivations for not taking any genuine responsibility for climate change, its goals of improving economic relations with the EU and benefiting from climate funds affected its consideration of joining the Kyoto regime. The worsening objective conditions have been influential in increasing the number of signatories of the Kyoto Protocol. Moreover, since the Protocol did not impel the non-Annex I parties to take serious measures, under these circumstances, Türkiye's preference has been to stay in the negotiations but not take responsibility for tackling climate change. The following section explains how this preference turns into a foreign policy

3.3. Kyoto regime analysis, step 3: from intentional dimension to foreign policy action

Türkiye’s preference of “being part of the climate regime yet taking no responsibility” became the most crucial determinant of Türkiye’s actions concerning the Kyoto regime. When the UNFCCC was adopted in 1992, Türkiye, as a member of the OECD, was included among the countries of the Convention’s Annex I and Annex II.[xlii] Being part of both Annex I and Annex II, if Türkiye wanted to maintain its energy security and industrial development, it could not have undersigned the responsibilities brought by the Kyoto Protocol. This position was officially announced as such: “Türkiye has chosen not to be a party to the convention due to the responsibilities brought to Annex I and Annex II countries.”[xliii] However, to benefit from climate funds and increase its economic integration with the EU, Türkiye preferred to remain a part of the regime, even if it did not ratify it. Accordingly, Türkiye decided that being excluded from the Annexes was the main preference in order to stay in the regime without taking responsibility. The main argument was that it was not possible for Türkiye to support developing countries as an Annex II member, since Türkiye was less developed than most of the countries it was obliged to support.[xliv]At the 7th Conference of the Parties held in 2001, Türkiye's name was finally removed from the list of Annex II countries. While remaining an Annex I country, it was also accepted that Türkiye had its own special circumstances.[xlv] Though its removal from Annex II enabled Türkiye to ratify the UNFCCC in 2004, it was not enough to become a part of the Kyoto Protocol. Stating that Türkiye was the country with the lowest emissions among Annex I countries,[xlvi] Türkiye also requested to be removed from the Annex I list.[xlvii] Even if it was removed from the Annex II list, being a signatory to the Protocol as an Annex I country would also bring to Türkiye important obligations and emission reduction responsibilities with reference to a base year. In the first commitment period that started in 2008, Türkiye, which did not have any responsibility as it was not yet a part of the Kyoto Protocol, finally decided to become a part of the regime by ratifying the Protocol in 2009. Türkiye had created a situation whereby it could ratify the Kyoto Protocol, as the Kyoto regime would not impose any responsibility on itself, and thus it could also possibly benefit from the support funds[xlviii] allocated in the UNFCCC.[xlix]

Türkiye’s policy of developing the coal-based energy sector has made it impossible to achieve the emission reduction target that the Kyoto regime expected from Türkiye, an Annex I country. Considering its growing population and economy, Türkiye had emphasized in official documents that it could not reduce its emissions by referring to a base year and that it was not possible for Türkiye to meet the Kyoto regime’s expectations.[l] Moreover, Türkiye’s value of prioritizing the interest of industry undermined the possibility of Türkiye taking more responsibility. For example, the iron-steel and cement sectors in the manufacturing industry, which brought an expeditious economic development in the short term, also increased carbon emissions quite rapidly, which caused Türkiye to further disconnect from the Kyoto regime. Even in the climate change plans announced after the drought experienced in 2007, which had a significant impact on Türkiye, the primary responsibility for combating climate change was placed on households and the savings to be made by households. As a result, Türkiye attempted to alleviate public pressure by making plans that would not affect industrial development. The interests of the industry continued to be protected by putting the responsibility on “Aunt Ayşe.”[li]

3.4. Kyoto Regime Analysis, Step 4: Collective Action

The structural causalities that disposed Türkiye’s preference also became influential in shaping other nation-states’ preferences. Türkiye’s preference of not taking genuine measures all while being part of the Kyoto regime might simply be conceptualized as ‘free-riding.’ Free-riding problems in international climate policy have been referred to by many seminal works to explain the lack of collective actions for environmental degradation. From the perspective of game theory, as Olson suggests, actors in any groups have incentives to free-ride off the group members’ efforts. In larger groups, this behavior will be adopted by more actors.[lii] This is because, in larger groups, there will be more to gain from the free-riding. Besides, it will be less likely to be punished since the cost of free-riding will be blurred as groups become larger. Nordhaus claims that the free-riding problems were one of the main reasons why the Kyoto Protocol failed and suggests that to overcome this issue, imposing sanctions on non-participants is a key solution.[liii] Furthermore, Napoli examines statements from 14 Annex I states’ public officials about growth in emissions to explain the Kyoto Protocol’s failure. As in the case of Türkiye, protecting the interest of industry and ensuring energy security were critically influential for those states.[liv] For the free riders of the Kyoto Protocol, the structural and dispositional incentives are alike. Due to the foreign policy actions of free-rider states like Türkiye, Kyoto Protocol targets could not be met, and the aggregation of these actions generated the Paris regime.

Even though the Kyoto Protocol is an extremely important agreement since it is the first environmental agreement that imposes certain responsibilities on states, the Kyoto regime has produced disappointing results. The information revealed by the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report published in 2014 showed that the period between 1983 and 2012 was the warmest 30-year period in the last 1,400 years and concluded that there is no doubt that the reason for this was human activities.[lv] Moreover, the data shared by the World Bank revealed that carbon emissions increased by 60 percent between 1990 and 2013, causing global temperatures to increase by 0.8 °C.[lvi] The increase in the last two decades also indicates that the Kyoto regime could not achieve its goals, and the longer we wait to reduce emissions, the more expensive it will become. So, the objective conditions made it essential to revise the failed Kyoto regime with a more effective agreement as soon as possible.

The main purpose of this new regime was to change the approach toward the fight against environmental degradation by involving more parties and emission reduction targets. Therefore, the distinguishing feature of the Paris Agreement was that the regime put responsibilities not only on developed countries but also on developing nations.[lvii] In other words, the Paris Agreement lifted the differentiation between Annex I and non-Annex I countries inscribed in the UNFCCC. The second distinguishing feature was the form of responsibility given to countries by the Paris Agreement. In Paris, unlike Kyoto, countries were given the opportunity to set their own targets instead of being subjected to common emission reduction targets for all countries. In other words, countries would set their emission reduction targets and undertake the responsibility in proportion to their capacities.[lviii] This change was extremely important in terms of convincing developing countries to take responsibility as well. The regime envisaged that all parties should submit their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) to the secretariats every five years and stick to the plan they submitted. In order to enhance the ambition over time, the Paris Agreement provided that successive NDCs should depict a progression compared to the previous NDC and reflect its highest possible ambition.[lix] As a result, the Paris Agreement emerged to keep the temperature increase well below 2 degrees above the preindustrial period, with the individual goals states had determined with their own consent. Akin to the Kyoto regime, the objective conditions concerning the Paris regime steered the states toward ratifying the agreement. Furthermore, the institutional settings, particularly the NDC system, gave states plenty of space to maneuver to avoid taking any severe action.

4.2. Paris regime analysis, step 2: from dispositional dimension to intentional dimension

After the 2008 economic crisis, energy security became more important due to the need to reduce production costs, while the demand for cheap energy increased rapidly as well. For this reason, Türkiye, which had increased its dependence on natural gas, also continued to increase its coal investments. This had been the main determinant for Türkiye concerning its energy security during the Paris regime. Several new coal power plants were established with support from the government in order to maintain Türkiye's “short-term gain-based” energy policy.[lx] As a result, while many EU and OECD countries started phasing out coal-powered generators and stopped building new plants, Türkiye's coal investments continued to increase. Thus, once again, Türkiye’s tendency to preserve its coal-based energy policy collided with the policies that support the struggle against climate change.

During this period, the construction, transportation, and energy sectors have come to the fore as the primary sectors that provide "hot money" investments to Türkiye for maintaining rapid economic development. Industrial interests were configured upon the urban transformation policies, the construction of coal power plants, and nuclear power plant projects. In addition, projects such as Kanal Istanbul have also led Türkiye to adopt an economic growth model led by construction and transportation. Therefore, high-carbon industrial development was again the key characteristic during this period.[lxi] Especially with the procurement law and construction zoning law that changed numerous times during this period, Türkiye preferred to protect the construction industry by putting aside concerns over ecological destruction and decent climate policy.

Economic integration with Europe continued to be an essential value of Türkiye's foreign policy in this period. Ever since the Union adopted a more structured strategy to lead the way in the global pursuit of climate action, to be unconcerned with international climate action has become more troublesome for Türkiye. However, it is crucial to stress that the Paris Agreement has not particularly encouraged Türkiye to pursue a genuine environmental policy. The emergence of the possibility of producing many high-carbon products in Türkiye, which EU countries have given up to combat climate change, had begun to be seen as a source of economic gain. In turn, this ironically caused Türkiye to move further away from the Paris Agreement and its climate targets to increase its economic integration with the EU.

Climate funds continued to be of great importance for Türkiye's climate policy in the Paris regime, as it was in the Kyoto regime. Those climate funds were crucial for Türkiye, so much so that Türkiye even prepared almost all the official climate reports through the use of such funds. In addition, it has been repeatedly stated by Türkiye in almost every COP meeting and national document that utilizing climate funds was vital for Türkiye's ability to combat climate change. For these reasons, Türkiye chose not to ratify the Paris Agreement for a long time, even if it was signed as early as 2016. Türkiye's biggest concern was that being a party to the Paris Agreement as an Annex I country might mean that Türkiye would not benefit from climate funds since it was classified as a developed country.

Like the Kyoto regime, due to the ‘easily achievable’ emission reduction targets, the structural dimension of the Paris regime constrains states to be part of the agreement. Moreover, the NDC solution promoted states to enter the Paris regime, yet at the same time, its non-binding character enables states to not take responsibility. For Türkiye, while the values of energy security and the interest of industry have been in conflict with genuine climate-neutral policies, the aims of improving economic relations with the EU and benefiting from climate funds are the driving factors to being part of the Paris regime. Besides, as pointed out, considering its economic relations with the EU, Türkiye benefited from producing high-carbon products. Under these circumstances, once again, Türkiye’s preference remained to be a part of the climate regime yet taking no responsibility.

4.3. Paris regime analysis, step 3: from intentional dimension to foreign policy action

Türkiye signed the Paris Agreement without taking responsibility and also managed to reach climate funds due to its preferences. Nevertheless, Türkiye declared that it signed the agreement as a "developing country."[lxii] Although the Paris Agreement can be ratified without annotation,[lxiii] the actual reason why Türkiye did so is that Türkiye still has a desire to benefit from different climate funds that might be on the table in the future. As in Kyoto, Türkiye developed a similar preference to the Paris regime and chose to remain a signatory to the regime without ratifying the agreement for a while, that is, to continue to be a part of the negotiations without taking responsibility. The most important step states had to take within the Paris regime was to prepare the NDC to be submitted to the secretariat of the Convention. Türkiye has prepared its NDC within the framework of the above-mentioned values. Therefore, forming a NDC that would not harm its economic development, industry interests, and carbon-intensive energy consumption and not taking responsibility within the Paris regime formed the mainstay for determining Türkiye's intention. Türkiye submitted its NDC to the UNFCCC secretariat on 30 September 2015 and declared that it would reduce its carbon emissions by 21 percent by 2030 compared to the business-as-usual scenario. The amount of emissions that Türkiye agreed to reduce, in fact, did not envisage any reduction. Its only aim was to reduce the projected carbon increase regarding Türkiye's foreseen economic growth and population increase.[lxiv] The emission reduction targets that Türkiye set have been criticized not only because they did not contain an actual reduction but also for being prepared inattentively.[lxv] In addition, these targets did not foresee any peak until 2030, nor did they foresee any peak after 2030 in which emissions would begin to decrease. The fact that the economic growth rate and the associated emission increase rate stated in the NDC were calculated so high meant that Türkiye would have achieved this target even if it did not put up a fight.[lxvi] The conclusion drawn from this is that Türkiye's NDC had been formed to depict that Türkiye intended to avoid any responsibility.

Even after submitting the NDC in a non-responsible manner, Türkiye continued to implement the "wait and see" policy as it did in the Kyoto process. Thus, Türkiye waited a long time to ratify the Paris Agreement. One of the primary reasons was the ongoing request of Türkiye to be removed from the Annex I membership. Türkiye wanted to be sure that being an Annex I country would not pose any problems in accessing climate funds, and so decided to wait until its access to funds would be guaranteed by the regime.[lxvii] The return of the US to the Paris regime in 2020 pushed Türkiye's stance to a pretty marginal position as one of the last six countries that did not ratify the Paris Agreement (192 out of 198 countries became a party to the Paris regime before Türkiye).

Finally, in the second half of 2021, Türkiye ratified the Paris Agreement in parliament and became a party to the Agreement. The pressure from the European countries was the main factor that directed Türkiye to sign the Agreement. Moreover, the three billion euros of green credit that two European countries (Germany and France) and the World Bank promised to provide to Türkiye enabled Türkiye to sign the Agreement.[lxviii] After Türkiye felt sure that accessing the green funds would not be a problem, Türkiye decided to withdraw its request to be removed from Annex I, which it had included in all previous agendas at COP meetings for nearly 20 years. Türkiye's chief climate negotiator, Birpınar, also approved that this request was withdrawn as a sign of goodwill after the funding had been promised to Türkiye.[lxix] The statement by Birpınar indicated how Türkiye's value is influential in determining its preferences. In addition to accessing the climate funds, Türkiye's preference for being a party without taking responsibility also successfully turned to policy action. In the end, even when Türkiye ratified the contract in late 2021, it had fixed itself in a position in which it would not have to take profound responsibility and could continue to be a free-rider inside the regime.

4.4. Paris regime action, step 4: collective action

Although the institutional settings of Kyoto and Paris are different, they both lack the binding mechanisms for states to take genuine climate measures. After the failure of the Kyoto Protocol, studies stressed the need for tightened emission limits and an effective agreement that introduces enforcement mechanisms.[lxx] The Paris Agreement was able to involve more actors in the climate regime, however, the NDC system failed to impose sanctions on non-participants. Thus, the Paris Agreement could not be successful in resolving the problem of free-riding. Moreover, the U.S.’s official withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in 2020 and the longstanding reluctance of states to commit to larger emission targets intensified the failure.[lxxi] To sum up, like in the case of Kyoto, due to the foreign policy actions of free rider states like Türkiye, the global emission targets could not be accomplished, and the deficiencies of the Paris Agreement led EU countries to take a new initiative to achieve the Paris Agreement's goals with different conditions. Thus, the European Green Deal was put into action.

After the Kyoto regime, the Paris regime also could not make the necessary contribution to the fight against climate change. As Climate Tracker has shown, almost no country can carry out a successful fight against climate change under the Paris regime.[lxxii] Moreover, from the beginning, it was apparent that it was impossible to keep global warming well below 2 degrees since the submitted NDCs of the parties are so inadequate in relation to the target. In addition, countries that took responsibility to combat climate change suffered economic losses due to the inaction of free-riding countries. The shift of production lines to free-rider countries that continue carbon-intensive production also prevented global emission rates from decreasing. Regardless of the desired reduction of emissions, the objective conditions got worse.[lxxiii] Eventually, the EU, which declared itself as the leader (climate leader) in the fight against climate change, finally put forth its own efforts in 2019 to achieve the goals and objectives set by the Paris Agreement: European Green Deal.

The European Green Deal is a policy initiative by the European Commission that aims to make Europe a carbon-neutral continent by 2050.[lxxiv] The primary purpose of the Green Deal is to achieve the political and economic transformation that will meet the criteria set by the Paris Agreement in the period leading up to 2050. Besides creating a carbon-neutral Europe, stimulating the economy and ensuring the protection of nature are the main objectives of the Green Deal.[lxxv] In the process of implementing the Green Deal, the EU emphasizes that it is extremely important for the success of the process that the partner countries also transform their production process in accordance with the Green Deal targets.[lxxvi] Otherwise, it does not seem possible to stop carbon leakage, and thus, it would be impossible for the EU to achieve its goals. There are Green Deal mechanisms that are relevant to this study. ‘The emission trading system mechanism’ is one of the primary means for that purpose, which has already been in use in Europe for a long time. The emission trading system, introduced to encourage companies to use clean energy and low-carbon production, aims to make companies pay for their emissions by determining emission limits every year. Along with reducing the total emission rates to be determined every year, it is seen as the main objective for companies to lower carbon emissions over the years. The second mechanism is ‘the carbon border adjustment mechanism.’ It is a carbon pricing policy that is planned to be applied to some goods coming from non-EU countries that have not implemented regulations comparable to the climate change policies implemented in the EU.[lxxvii] Hence, the mechanism's primary goal is to level the playing field between European and non-European producers. So, non-EU producers have to set the same standards as EU producers applied, and they have to pay the same carbon price when they do not apply the standards put in place by the EU. This mechanism will affect all countries that trade with the EU and will affect countries that do not take efficient steps and do not uphold their responsibilities for climate change.

Just like the objective conditions of the Kyoto and Paris regimes, the scientific climate facts concerning the Green Deal period most certainly constitute the key reasons for actors to pursue a profound multilateral climate initiative. The objective conditions generate substantially similar causality in all three temporal dimensions. Moreover, whereas the institutional settings for the Paris and Kyoto regimes are considerably alike in terms of not compelling the actors to take genuine measures, the Green Deal introduces a rather different approach. Unlike other climate regime regulations, the two mechanisms mentioned above are binding for all the relevant actors. In this regard, the Green Deal regulations signify a radical change in the structural dimension that might increase constraints on actors to conduct policies that are compatible with emission reduction targets. Since it has been released recently, we are unable to make an accurate analysis of Türkiye’s position on this new structure. Based on the account developed in this study, we will conclude by speculating how the preference of Türkiye may alter.

Figure 4: Turkish Foreign Policy on Climate Regimes: An Overview[lxxviii]

In this paper, we examine the continuity and change of Turkish foreign policy on climate regimes via Carlsnaes’ tripartite approach. The present study ascertains that since the foundation of the UNFCCC in 1992, some causal dynamics between the structure of climate regimes and Türkiye’s foreign policy actions are considerably durable. Whereas the Kyoto and Paris regimes had drastic structural incentives to drive states to be part of the climate agreements, they lacked the procedures to force actors to take profound measures to limit carbon emissions. Under these circumstances, in accordance with its values, Türkiye’s preferences are to be a part of climate regimes but to take no responsibility.

As it is proposed in this study, Türkiye has four core values concerning environmental politics. Under the Green Deal circumstances, we believe, these values will be the key motives to determine its preferences. For many years, the EU has been Türkiye's largest export and import partner. With a longstanding value of “increasing the economic integration with Europe,” Türkiye had developed an intention by sacrificing the fight against climate change to develop its exports to the EU and produce lots of 'low-tech carbon-intensive products' under the Kyoto and Paris regimes. However, in this new structure, in order to preserve and develop economic integration with the EU, Türkiye will be compelled to follow the Green Deal mechanisms. Before, in not taking any responsibility, Türkiye has not suffered any economic damage; on the contrary, it increased its profits by increasing its exports to EU countries. This dynamic seems to have vanished soon via new regulations. For instance, with the activation of the carbon adjustment mechanism, it will not be possible to export carbon products to Europe without paying the carbon tax. As a result, it will not be possible for Türkiye to increase its economic integration with the EU without taking responsibility within the climate regimes anymore.

Energy security was another value for Türkiye to determine its preferences. Türkiye has ensured its energy security with a coal-based energy policy so far. However, it seems that if Türkiye aims to continue trade with the EU on fair terms, it needs to gradually change its intention and move away from the use of coal. Otherwise, the carbon tax that Türkiye will pay to EU countries will be so high that exporting these products may become meaningless. Preserving the interests of the industry is considered another value for Türkiye. If Türkiye had taken responsibility during the Kyoto and Paris regimes, it would have been able to allocate resources to new investments and use clean energy resources, waste management, etc. Eventually, it could face the risk of losing its profitability. However, due to the implementation of the Carbon Adjustment Mechanism, the Green Deal requires Türkiye to take some initiatives this time to protect the interests of its industries. Otherwise, it seems highly probable that many export companies may lose their export power. In fact, in recent months, industrial organizations have started to encourage the Turkish Republic to ratify the Paris Agreement and adapt to the Green Deal,[lxxix] which should have happened in the opposite way under normal circumstances. Lastly, climate funds are examined as a value for Türkiye that drives Türkiye’s preferences. Even though this value explains many causalities for the Kyoto and Paris regimes, in the Green Deal structure, it will be relatively ineffective. So far, the EU has not announced any grants in the Green Deal framework for non-member states to promote climate actions. Nevertheless, we suppose, new funds released in the future would be influential for ascertaining Türkiye’s preferences just like it did before.

The climate policy of Türkiye has remained constant since the beginning of the climate regimes. This continuity has developed in line with the structural causalities and Türkiye's interests, shaped by its values, and has led Türkiye to be part of climate regimes in different ways while not taking genuine responsibility. As long as Türkiye did not take responsibility, it had the opportunity to protect its core values. This situation was implemented by Türkiye and many other countries in similar ways. The fact that many countries did not contribute positively to the climate regimes and chose not to take responsibility weakened the structures. At last, the EU took its leadership one step further and prepared a plan that would invite the member nations and countries that trade with the EU to take the initiative.

Türkiye may have to turn to different intentions and, therefore, a different policy action this time, in order to preserve its values. Otherwise, it does not seem possible for the country to protect and maintain its values, which they previously protected by not taking responsibility, without taking responsibility this time. The continuity seen in Türkiye's climate policy thus far has the potential to be replaced by complying with the European Green Deal. Even though Türkiye signed the Paris Convention without taking any responsibility, this signature, which came years later, points to the change that the Green Deal has already created in Türkiye's intentions. Türkiye's chief climate negotiator also emphasized that one of the most important reasons for Türkiye's ratification of the Paris regime was its attempt to adapt to the Green Deal's responsibilities.[lxxx] The possibility that Türkiye will prepare the successive NDC to be compatible with this has now appeared on the horizon. As such, it also seems possible Türkiye may adopt a greater sense of responsibility moving forward. Fingers crossed!

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the comments, suggestions, and contributions of Thomas King, Muhammed Ali Ağcan, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors at All Azimuth. Of course, these individuals bear no responsibility for any errors that may remain.

Notes

[i] Darrel Moellendorf, “Climate Change and Global Justice,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 3, no. 2 (2012): 131-143; Mohammed Hassan Shakil et al., “COVID-19 and the Environment: A Critical Review and Research Agenda,” Science of the Total Environment 745, no. 9 (2020): 1-8; Matheus Koengkan and José Alberto Fuinhas, “Is Gender Inequality an Essential Driver in Explaining Environmental Degradation? Some Empirical Answers from the CO2 Emissions in European Union Countries,” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 90 (2021): 1-14.

[ii] Gideon Rose, “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy,” World Politics 51, no. 1 (1998): 144-172; Walter Carlsnaes, “How Should We Study the Foreign Policies of Small European States?” Nação e Defesa 118, no. 3 (2007): 7-20; Elisabetta Brighi, Foreign Policy, Domestic Politics, and International Relations (London, UK: Routledge, 2013).

[iii] Walter Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem in Foreign Policy Analysis,” International Studies Quarterly 36, no. 3 (1992): 245-270.

[iv] In this context, the concept of regime might signify two meanings: Regime as a formal international framework and regime that is widely used by International Relations scholarship and is not necessarily related to an international agreement. In International Relations literature, there are several definitions of regime. In this paper, we particularly use the concept of regime as “multilateral agreements among states which aim to regulate national actions within an issue area” (See Stephan Haggard and Beth A. Simmons. “Theories of International Regimes,” International Organization 41, no. 3 (1987): 493-496). Therefore, we do not claim that the agreements that will be analyzed in this paper are different ‘formal’ international regimes. Our use of regime as a concept is a purely analytical preference. We thank both anonymous referees for drawing our attention to this to prevent a potential misunderstanding.

[v] Milja Kurki and Colin Wight, “International Relations and Social Science,” in International Relations Theories, ed. Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki and Steve Smith, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013), 20.

[vi] Robert. O. Keohane, “International Institutions: Two Approaches,” International Studies Quarterly 32, no. 4 (1988): 379–96; Martin Hollis and Steve Smith, Explaining and Understanding International Relations (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 2009).

[vii] Alexander Wendt, “Bridging the Theory/Meta-theory Gap in International Relations,” Review of International Studies 17, no. 4 (1991): 383-92; Martin Hollis and Steve Smith, “Beware of Gurus: Structure and Action in International Relations,” Review of International Studies 17, no. 4 (1991): 393-410; Alexander Wendt, “Levels of Analysis vs. Agents and Structures: Part III,’ Review of International Studies 18, no. 2, (1992): 181-185; Martin Hollis and Steve Smith, “Structure and Action: Further Comment,” Review of International Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 187-188.

[viii] Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem,” 247.

[ix] Roy Bhaskar, “On the Society / Person Connection,” in The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences (London, UK: Routledge, 2014), 38.

[x] Margaret S. Archer, Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

[xi] Margaret G. Hermann and Joe D. Hagan, Leaders, Groups, and Coalitions: Understanding the People and Processes in Foreign Policymaking (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishers, 2002); Margaret G. Hermann, “Assessing Leadership Style: Trait Analysis,” in The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders: With Profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton, ed. Jerrold M. Post (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005); Philip A. Schrodt, “Artificial Intelligence and International Relations: An Overview,” in Artificial Intelligence and International Politics, ed. Valerie Hudson (New York City, NY: Routledge, 2019), 9-31.

[xii] Walter Carlsnaes, “Foreign Policy,” in Handbook of International Relations, ed. Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse-Kappen, and Beth A. Simmons (London, UK: Sage, 2002), 316-17.

[xiii] Carlsnaes, “How Should We Study the Foreign Policies of Small European States?”

[xiv] Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem,” 250.

[xv] Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem,” 260.

[xvi] Walter Carlsnaes, “Where is the Analysis of European Foreign Policy Going?,” European Union Politics 5, no. 4 (2004): 495-508.

[xvii] Carlsnaes, “Foreign Policy,” 317.

[xviii] Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem”; Carlsnaes, “Where is the Analysis of European Foreign Policy Going?”

[xix] Walter Carlsnaes, “Actors, Structures, and Foreign Policy Analysis,” in Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases, ed. Steve Smith, Amelia Hadfield, and Tim Dunne, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008), 127.

[xx] Carlsnaes, “The Agency-Structure Problem,” 264.

[xxi] Bhaskar, “Some Emergent Properties of Social Systems,” 42.

[xxii] Created by the authors based on several works of Walter Carlsnaes, cited before.

[xxiii] Kuniko P. Ashizawa, “Building the Asia-Pacific: Japanese and US Foreign Policy Toward the Creation of Regional Institutions, 1988-1994” (Ph.D. diss., Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, 2005), 59.

[xxiv] Ashizawa, “Building the Asia-Pacific,” 61.

[xxv] Ashizawa, “Building the Asia-Pacific,” 53-59.

[xxvi] Created by the authors.

[xxvii] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC, “IPCC 2007: Summary for Policymakers,” in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis – Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. Susan Solomon et al., (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1-18.

[xxviii] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - UNFCCC, “Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” paper presented at Kyoto Climate Change Conference of the United Nations, Kyoto, JP, December 1997. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/250111.

[xxix] UNFCCCC, “Kyoto Protocol - Article 2, 3, and 4.”

[xxx] UNFFCCC, “Kyoto Protocol - Article 11.”

[xxxi] International Energy Agency - IEA, Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Turkey 2009 Review (Paris, FR: OECD Publishing, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264060425-en.

[xxxii] Ministry of Environment and Forestry, First National Communication of Turkey on Climate Change to UNFCCC, ed. Günay Apak and Bahar Ubay, (Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2007). https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/turnc1.pdf

[xxxiii] Ümit Şahin et al., Coal Report: Turkey’s Coal Policies related to Climate Change, Economy, and Health (Istanbul, Turkey: Istanbul Policy Center, 2016), 7-8.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] State Planning Organization of the Turkish Prime Ministry, Uzun Vadeli Strateji ve Beş Yıllık Kalkınma Planı VIII 2001-2005 [Long-Term Strategy and Five-Year Development Plan VIII 2001-2005] (Ankara, Turkey: State Planning Organization, 2000).

[xxxvi] Turkish Industry and Business Association - TÜSİAD, Ekonomi Politikaları Perspektifinden İklim Değişikliği ile Mücadele [Struggle with Climate Change from the Perspective of Economy Policies] (Ankara, Turkey: TÜSİAD, 2016), 43.

[xxxvii] Ümit Şahin “Başlangıcından Bugüne Uluslararası İklim Değişikliği Rejimi,” in Uluslararası Çevre Rejimleri, ed. Semra Cerit Mazlum, Yasemin Kaya, and Gökhan Orhan, (Bursa: Dora, 2017), 117.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 123.

[xxxix] TÜSİAD, İklim Değişikliği ile Mücadele, 43.

[xl] Ümit Şahin, “Warming A Frozen Policy: Challenges to Turkey’s Climate Politics After Paris,” Turkish Policy Quarterly 15, no.2 (2016): 125.

[xli] Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, National Climate Change Action Plan 2010–2023 (Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2012), 9.

[xlii] Ministry of Environment and Forestry, First National Communication of Turkey, 6.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Şahin, “Uluslararası İklim Değişikliği Rejimi.”

[xlv] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - UNFCCC, “Amendment to the list in Annex II to the Convention, Decision 26 / Chapter 7,” United Nations Climate Change, 2001, https://unfccc.int/documents/2521.

[xlvi] Ethemcan Turhan et al., “Beyond Special Circumstances: Climate Policy in Turkey 1995–2015,” WIREs: Interdisciplinary Reviews on Climate Change 7, no.3 (2016): 449.

[xlvii] “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol – 1.UNFCCC and Türkiye’s Position,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2022, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change-_unfccc_-and-the-kyoto-protocol.en.mfa

[xlviii] As stated in the text, Türkiye thought that it would gain access to climate funds after its special circumstance was recognized (https://www.mfa.gov.tr/united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change-_unfccc_-and-the-kyoto-protocol.en.mfa). However, as a remaining Annex I member, Türkiye actually was only eligible for the Capacity Building Support, not for the climate funds.

[xlix] Semra Cerit Mazlum, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy on Global Atmospheric Commons: Climate Change and Ozone Depletion,” in Climate Change and Foreign Policy – Case Studies from East to West, ed. Paul G. Harris, (London, UK: Routledge, 2012), 75.

[l] Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, National Climate Change Action Plan 2010–2023 (Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2010). https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/iklim/editordosya/iklim_degisikligi_stratejisi_EN(2).pdf.

[li] Nuran Talu, Türkiye'de İklim Değişikliği Siyaseti [Politics of Climate Change in Turkey] (Ankara, Turkey: Phonenix, 2015), 351.

[lii] Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action, Vol. 124. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

[liii] William Nordhaus, “Climate Clubs: Overcoming Free-riding in International Climate Policy,” American Economic Review 105, no.4 (2015): 1339-1370.

[liv] Christopher Napoli, “Understanding Kyoto's Failure,” The SAIS Review of International Affairs 32, no.2 (2012): 190-191.

[lv] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – IPCC “Climate Change, 2014: Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers,” IPCC, 2014, 2. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

[lvi] Tariq Khokhar, “Chart: CO2 Emissions are Unprecedented,” World Bank Blogs, 2017. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/chart-co2-emissions-are-unprecedented.

[lvii] Chukwumerije Okereke and Philip Coventry, “Climate Justice and the International Regime: Before, during, and after Paris,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 7, no. 6 (2016): 838-40.

[lviii] Ibid., 841.

[lix] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – UNFCCC, “Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” paper presented at Paris Climate Change Conference of United Nations, Paris, FR, December, 2015. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

[lx] Erinç Yeldan and Ebru Voyvoda, Türkiye için Düşük Karbonlu Kalkınma Yolları ve Öncelikleri [Low Carbon Development Pathways and Priorities for Turkey] (Istanbul, Turkey: Istanbul Policy Center, 2015), 46-48.

[lxi] Fikret Adaman and Murat Arsel, “Climate Policy in Turkey: A Paradoxical Situation?,” L’ Europe En Formation 380, no.2 (2016): 36.

[lxii] Malak Altaeb, “Turkey Finally Ratified the Paris Agreement. Why Now?,” Middle East Institute, 2021. https://www.mei.edu/publications/Turkey-finally-ratified-paris-agreement-why-now.

[lxiii] Isil Sariyuce and Caitlin Hu, “Turkey Finally Ratifies Paris Climate Agreement but Protests Key Detail,” CNN, 2021. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/10/06/world/Turkey-ratify-paris-climate-agreement-intl/index.html.

[lxiv] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - UNFCCC, the Republic of Turkey Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (Ankara, Turkey: UNFCC, 2015).

[lxv] “Countries – Find Your Country,” Climate Action Tracker, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/.

[lxvi] Şahin, “Warming A Frozen Policy,” 123.

[lxvii] Mehmet Emin Birpınar, “Turkey does not have a Luxury to be a Laggard in terms of Climate Action,” İklim Haber, interview by Melis Alphan, 2018. https://www.iklimhaber.org/chief-climate-negotiator-turkey-does-not-have-a-luxury-to-be-a-laggard-in-terms-of-climate-action/.

[lxviii] Karl Mathiesen, “Europe Offered Turkey Cash to Join Paris Climate Accord,” Politico, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-turkey-join-paris-agreement-climate-money/.

[lxix] “Türkiye iklim değişikliği zirvesinde statü değişikliği talebini geri çekti,” BloombergHT, 2021. https://www.bloomberght.com/turkiye-iklim-zirvesinde-statu-degisikligi-talebini-geri-cekti-2291117.

[lxx] Scott Barret, “Climate Treaties and the Imperative of Enforcement,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24, no.2 (2008): 239-258.

[lxxi] Simone Tagliapietra and Guntram B. Wolff, “Conditions are Ideal for a New Climate Club,” Energy Policy 158 (2021): 1-5.

[lxxii] “Overview of Turkey,” Climate Action Tracker. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/Turkey/.

[lxxiii] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers,” in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis - Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. Richard Philip Alan et al., (Geneva, CH: WMO – IPCC Secretariat, 2021).

[lxxiv] Sarah Wolf et al., “The European Green Deal — More Than Climate Neutrality,” Intereconomics 56, no.2 (2021): 99.

[lxxv] European Commission, “The European Green Deal,” Communication from the Commission – COM, 2019. https://commission.europa.eu/publications/communication-european-green-deal_en.

[lxxvi] European Commission, “The European Green Deal, Introduction - Turning an Urgent Challenge into a Unique Opportunity.”

[lxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxviii] Created by the authors.

[lxxix] “İş İnsanlarından Çağrı: “Paris İklim Anlaşması'nı Onaylayın,” Cumhuriyet, 2021, https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/is-insanlarindan-cagri-paris-iklim-anlasmasini-onaylayin-1843285.

[lxxx] “AB’nin Karbon Vergisi, Türkiye’nin Paris Sözleşmesi’ni Onaylamasında Önemli Rol Oynadı,” Euronews 2021, https://tr.euronews.com/2021/11/08/ab-nin-karbon-vergisi-turkiye-nin-paris-sozlesmesi-ni-onaylamas-nda-onemli-rol-oynad.

“AB’nin Karbon Vergisi, Türkiye’nin Paris Sözleşmesi’ni Onaylamasında Önemli Rol Oynadı [EU's Carbon Tax

Played an Important Role in Turkey's Ratification of Paris Convention].” Euronews, 2021. https://tr.euronews.com/2021/11/08/ab-nin-karbon-vergisi-turkiye-nin-paris-sozlesmesi-ni-onaylamas-ndaonemli-rol-oynad.

Adaman, Fikret, and Murat Arsel. “Climate Policy in Turkey: A Paradoxical Situation?.” L’ Europe En Formation 380, no.2 (2016): 26-38.

Altaeb, Malak, “Turkey finally ratified the Paris Agreement. Why now?.” Middle East Institute, 2021. https://www.mei.edu/publications/Turkey-finally-ratified-paris-agreement-why-now.

Archer, Margaret S. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Ashizawa, Kuniko P. “Building the Asia-Pacific: Japanese and US Foreign Policy Toward the Creation of Regional Institutions, 1988-1994.” Ph.D. dissertation. Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, 2005.

Barret, Scott. “Climate Treaties and the Imperative of Enforcement.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24, no.2 (2008): 239-258.

Bhaskar, Roy. “On the Society / Person Connection.” In The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences, 34-40. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2014.

Bhaskar, Roy. “Some Emergent Properties of Social Systems.” In The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences, 41-47. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2014.

Birpınar, Mehmet Emin. “Turkey does not have a Luxury to be a Laggard in terms of Climate Action.” İklim Haber. Interview by Melis Alphan, 2018. https://www.iklimhaber.org/chief-climate-negotiator-turkey-does-not-havea-luxury-to-be-a-laggard-in-terms-of-climate-action/.

Brighi, Elisabetta. Foreign Policy, Domestic Politics, and International Relations. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2013.

Carlsnaes, Walter. “Actors, Structures, and Foreign Policy Analysis.” In Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases, edited by Steve Smith, Amelia Hadfield, and Tim Dunne, 113-129. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2008. Carlsnaes, Walter. “Foreign Policy.” In Handbook of International Relations, edited by Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse-Kappen, and Beth A. Simmons, 298-325. London, United Kingdom: Sage, 2002. Carlsnaes, Walter. “How Should We Study the Foreign Policies of Small European States?.” Nação e Defesa 118, no.3 (2007): 7-20.

Carlsnaes, Walter. “The Agency-Structure Problem in Foreign Policy Analysis.” International Studies Quarterly 36, no.3 (1992): 245-270.

Carlsnaes, Walter. “Where is the Analysis of European Foreign Policy Going?.” European Union Politics 5, no.4 (2004): 495-508.

Cerit Mazlum, Semra. “Turkey’s Foreign Policy on Global Atmospheric Commons: Climate Change and Ozone Depletion.” In Climate Change and Foreign Policy – Case Studies from East to West, edited by Paul G. Harris, 68-84. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2012.

“Countries – Find Your Country.” Climate Action Tracker, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/. European Commission. “The European Green Deal.” Communication from the Commission – COM, 2019. https://commission.europa.eu/publications/communication-european-green-deal_en.

Hagan, Joe D. “Does Decision Making Matter?” In Leaders, Groups, and Coalitions: Understanding the People and Processes in Foreign Policymaking, edited by Margaret G. Hermann and Joe D. Hagan, Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell Publishers, 2002.

Haggard, Stephan, and Beth A. Simmons. “Theories of International Regimes.” International Organization 41, no. 3 (1987): 493-496.

Hermann, Margaret G. “Assessing Leadership Style: Trait Analysis.” In The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders: With Profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton, edited by Jerrold M. Post. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Hollis, Martin, and Steve Smith. “Beware of Gurus: Structure and Action in International Relations.” Review of International Studies 17, no.4 (1991): 393-410.

Hollis, Martin, and Steve Smith. “Structure and Action: Further Comment.” Review of International Studies 18, no.2 (1992): 187-188.

Hollis, Martin, and Steve Smith. Explaining and Understanding International Relations. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press, 2009.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC. “Climate Change, 2014: Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers.” IPCC, 2014, 2. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC. “IPCC 2007: Summary for Policymakers.” In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis – Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Susan Solomon et al., 1-18. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - IPCC. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis - Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Richard Philip Alan et al. Geneva, Switzerland: WMO – IPCC Secretariat, 2021.

International Energy Agency - IEA. Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Turkey 2009 Review. Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264060425-en.

“İş İnsanlarından Çağrı: “Paris İklim Anlaşması’nı onaylayın [Call from Business People: Approve Paris Climate Agreement].” Cumhuriyet, 2021. https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/is-insanlarindan-cagri-paris-iklimanlasmasini-onaylayin-1843285.

Keohane, Robert. O. “International Institutions: Two Approaches.” International Studies Quarterly 32, no. 4 (1988): 379–96.

Khokhar, Tariq. “Chart: CO2 Emissions are Unprecedented.” World Bank Blogs, 2017. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/chart-co2-emissions-are-unprecedented.

Koengkan, Matheus, and José Alberto Fuinhas. “Is Gender Inequality an Essential Driver in Explaining Environmental Degradation? Some Empirical Answers from the CO2 Emissions in European Union Countries.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 90 (2021): 1-14.

Kurki, Milja, and Colin Wight. “International Relations and Social Science.” In International Relations Theories, edited by Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki and Steve Smith, 14-35. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Mathiesen, Karl. “Europe Offered Turkey Cash to Join Paris Climate Accord.” Politico, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-turkey-join-paris-agreement-climate-money/.

Ministry of Environment and Forestry. First National Communication of Turkey on Climate Change to UNFCCC, edited by Günay Apak, and Bahar Ubay. Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2007. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/turnc1.pdf

Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. National Climate Change Action Plan 2010–2023. Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2012. https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/iklim/editordosya/iklim_degisikligi_stratejisi_EN(2).pdf.

Moellendorf, Darrel. “Climate Change and Global Justice.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 3, no.4 (2012): 131-143.

Napoli, Christopher. “Understanding Kyoto’s Failure.” The SAIS Review of International Affairs 32, no.2 (2012): 183-196.

Nordhaus, William. “Climate Clubs: Overcoming Free-riding in International Climate Policy.” American Economic Review 105, no.4 (2015): 1339-1370.

Okereke, ChUnited Kingdomwumerije, and Philip Coventry. “Climate Justice and the International Regime: Before, during, and After Paris.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 7, no. 6 (2016): 834-851.

Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action, Vol. 124. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009.

“Overview of Turkey,” Climate Action Tracker. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/Turkey/.

Rose, Gideon. “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy.” World Politics 51, no.1 (1998): 144-172.

Şahin, Ümit, Ahmet Atıl Aşıcı, Sevil Acar, Pınar Gedikkaya-Bal, Ali Osman Karababa, and Levent Kurnaz. Coal Report: Turkey’s Coal Policies related to Climate Change, Economy and Health. Istanbul, Turkey: Istanbul Policy Center, 2016.

Şahin, Ümit. "Başlangıcından Bugüne Uluslararası İklim Değişikliği Rejimi [The International Climate Change Regime from the Beginning to the Present]." In Uluslararası Çevre Rejimleri [Global Environment Regimes]. Edited by Semra Cerit Mazlum, Yasemin Kaya, and Gökhan Orhan, 67-130. Bursa: Dora, 2017.

Şahin, Ümit. “Warming A Frozen Policy: Challenges to Turkey’s Climate Politics After Paris.” Turkish Policy Quarterly 15, no.2 (2016): 117-129.

Sariyuce, Isil, and Caitlin Hu. “Turkey Finally Ratifies Paris Climate Agreement but Protests Key Detail.” CNN, 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/10/06/world/Turkey-ratify-paris-climate-agreement-intl/index.html.

Schrodt, Philip A. “Artificial Intelligence and International Relations: An Overview.” In Artificial Intelligence and International Politics, edited by Valerie Hudson, 9-31. New York City, New York: Routledge, 2019.

Shakil, Mohammad Hassan, Ziaul Haque Munim, Mashiyat Tasnia, and Shahin Sarowar. “COVID-19 and the Environment: A Critical Review and Research Agenda.” Science of the Total Environment 745, no. 9 (2020): 1-8.

State Planning Organization of the Turkish Prime Ministry, Uzun Vadeli Strateji ve Beş Yıllık Kalkınma Planı VIII 2001-2005 [Long-Term Strategy and Five-Year Development Plan VIII 2001-2005]. Ankara, Turkey: State Planning Organization, 2000.

Tagliapietra, Simone, and Guntram B. Wolff. “Conditions are Ideal for a New Climate Club.” Energy Policy 158 (2021): 1-5.

Talu, Nuran. Türkiye’de İklim Değişikliği Siyaseti [Politics of Climate Change in Turkey]. Ankara, Phonenix, 2015.

Turhan, Ethemcan, Semra Cerit Mazlum, Ümit Şahin, Alevgül H. Şorman, and A. Cem Gündoğan. “Beyond Special Circumstances: Climate Policy in Turkey 1995–2015.” WIREs: Interdisciplinary Reviews on Climate Change 7, no.3 (2016): 448-460.

Türk Sanayicileri ve İş İnsanları Derneği – TÜSİAD. Ekonomi Politikaları Perspektifinden İklim Değişikliği ile Mücadele [Struggle with Climate Change from the Perspective of Economy Policies. Ankara, Turkey: TÜSİAD, 2016.

“Türkiye iklim değişikliği zirvesinde statü değişikliği talebini geri çekt [Türkiye withdrew its status change request during the Climate Change Summit]i.” BloombergHT, 2021. https://www.bloomberght.com/turkiye-iklimzirvesinde-statu-degisikligi-talebini-geri-cekti-2291117.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – UNFCCC. the Republic of Turkey Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (Ankara, Turkey: UNFCC, 2015).

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – “Amendment to the list in Annex II to the Convention, Decision 26/ Chapter 7.” 2001, https://unfccc.int/documents/2521.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – “Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.” Paper presented at Kyoto Climate Change Conference of the United Nations. Kyoto, Japan, December 1997. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/250111.