Nergiz Özkural Köroğlu, Üsküdar University

Fatih Özgüven, Independent Researcher

Abstract

In a multipolar world, new security threats have emerged, and region-based approaches have been developed to address these new security challenges. In the literature on regionalisation, it is assumed that region-building processes take place under certain conditions and in certain stages. Considering the existing processes in the literature, this study aligns the formation of the Black Sea Region with the understanding of the stages of region-building and proposes new stages of region-building, influenced by the first and second waves of regionalisation processes. In order to analyse Türkiye’s role in the region, the statements made by Turkish political elites (Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, President, and Presidential Spokesperson) during their visits to the Black Sea countries (Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia) between 2014 and 2023 were subjected to content analysis. This period was chosen to highlight the post-2014 period, which witnessed conflicts that negatively affected the region-building process. Security concerns are important in region-building processes and often lead to the formation of security communities.

In the post-Cold War period, the increasing complexity and diversity in politics created new social units that started to have multifaceted interactions in the international structure. As a result, the significance of regions has increased, as they are not just where international relations are experienced, but also where they are created.[i] Björn Hettne and Fredrik Söderbaum also attributed the renewed rise of regionalism to the changing structure of the system.[ii] In addition, new security threats surfaced and, in this new political environment, region-based approaches emerged in order to deal with new security challenges.[iii] Regional formulations have thus started to lead to important repercussions in the security domain.

The basis for regionalisation studies was the adoption of the UN Territorial Charter in 1945 and the subsequent economic study of regionalism in the new post-war economic order. During this period, regionalism was discussed in relation to the expansion of the Bretton Woods system and whether economic cooperation between the blocs could be achieved during the Cold War.[iv] The first wave of regional studies put forward the concept of “region” based on geography, social institutions, and the sharing of common culture and historical legacy.[v] Therefore, geographic proximity, common historical heritage, and common culture between the states in a region would facilitate economic cooperation, which would be the basis for regionalism. In this period, the evolution of European integration became a significant case for regionalism studies.

In the context of the second wave of regionalisation, “regionness” refers to the ability of a region to take an active role in promoting its interests and influencing transnational affairs, rather than just being a passive geographic entity. The process of building a region is ongoing and dynamic, and regions are not fixed or unchanging. Instead, regions develop, grow, and may decline over time based on varying degrees of regionness, which is the extent to which a region is able to articulate and pursue transnational interests. In short, the level of regionness determines how well a region can build and sustain itself over time.[vi] The second wave of regionalisation, which arose in the 1990s, emphasises the role of non-state actors and informal relations rather than the role of formal institutions. Within the regionalism process, a social structure emerges, and the formal and informal units interact.[vii] In addition, the second wave sees regionalisation as a project and a process involving different actors, takes into account social integration between regions, and claims that regionalisation is not limited to politics and economics, but that social and cultural factors are also important.[viii] Filippo Costa Buranelli emphasises that the social connection of regionalisation is the form of “regional international society,” which differs from the regional global level and is regionally specific structures that separate and differentiate entities as a regional entity.[ix] In a regional international society, within a shared “linguistic structure,” the same institution can have different meanings, interpretations, or understandings in different regional contexts. Institutions may share the same language and understanding, but they may have different discourses and actions in different situations. Brunelli took some common elements of society, such as democracy, international law, and sovereignty, as examples of this and argued that these were understood and interpreted differently in the African and Middle Eastern regions, and that this situation can be seen as a “localisation of the norm.”[x] Amitav Acharya argues that the interaction between regional social units of the international society is important, and he notes that the unique features of a given region can influence how norms are diffused and applied within that region.[xi] In addition, Barry Buzan and Ana Gonzalez Pelaez argue that for a regional international society to emerge, there must first be differentiated institutions or unique linkages at the global level, and that this can be achieved either by eliminating the global entity or through patterns of understanding.[xii]

We would like to highlight “regional security” as a unique stage (fifth stage) based on the approach of Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, who, proposing to make sense of security, created the regional level, which can be influenced by the global power structure, to be included among the units of analysis. Buzan and Wæver developed this regional approach to understand international security in the Cold War era. According to the regional security complex theory (RSCT) they proposed, they claimed that threats increase according to proximity and distance in the formation of regional security.[xiii] Buzan’s RSCT emphasises that security sectors (including economic, environmental, and social) have two kinds of effects on the formation of complexes: one is to add different operational characteristics, and the other is to bring them together. As a result, Buzan claims that, complexes are more heterogeneous and there is no fixed regional security complex.[xiv]

In this study, which examines region-building processes through the case study of Türkiye, Buzan's approach to regional security is considered a key framework for analysing the stages involved in region-building, particularly the fifth stage. How Türkiye’s policies in the Black Sea Region-building processes are constructed within the framework of the region-building stages (identification of the region, establishment of historical and political relations, establishment of regional cooperation, geo-psychological aspect of the region, and construction of regional security) is scrutinized in this study. It should be emphasised that these stages are influenced by the first- and second-wave regionalisation literature. In this way, an attempt has been made to present a unique stage of region-building. In this study, the regionalisation analysis parameter is at the level of “state relations,” and the hypothesis that security is at the forefront of the Black Sea Region-building process in the discourse of Turkish political elites will be tested. Second, it is believed that as long as there are regional conflicts in the region-building process, the formation of a regional identity seems to be difficult. In this case, we believe that the security construction process is the backbone of the creation of a “regional international society.”

If we look at the literature on the region-building process of the Black Sea Region, there are several academic studies on the formation and processes of regionalisation that question the type of region the Black Sea constitutes.[xv] There are other studies based on the regionalisation of the Black Sea in the context of the EU.[xvi] In the process of building security in the Black Sea Region, there are studies on what should be done to prevent conflict and the creation of an insecure environment in the region, and to ensure security and cooperation.[xvii] Finally, there are studies on Turkish foreign policy towards the Black Sea Region and Türkiye’s role in the Black Sea Region-building processes and security.[xviii]

1.1. Methodology

In the region-building process, discourse is important.[xix] Discourse is carried out by the actors who make up the region, using their own codes in the public space for the building of the region. In a “regional international society,” the discourse, which is used in formal and informal units, has a significant role in the process.[xx] In this study, new stages of region-building, influenced by the first and second waves of regionalisation processes, have been proposed, and Turkish political elites’ discourses about Türkiye’s role in the Black Sea Region-building process are analysed by considering these stages and endorsed by content analysis. For the content analysis of Turkish political elites, the starting point will be 2014, which is the year of Crimea’s illegal annexation. Another important aspect in the Black Sea Region is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, starting in February 2022. Developments until December 2023 are included in the analysis. In the contextual framework, Türkiye’s role in the Black Sea Region is comprehensive.

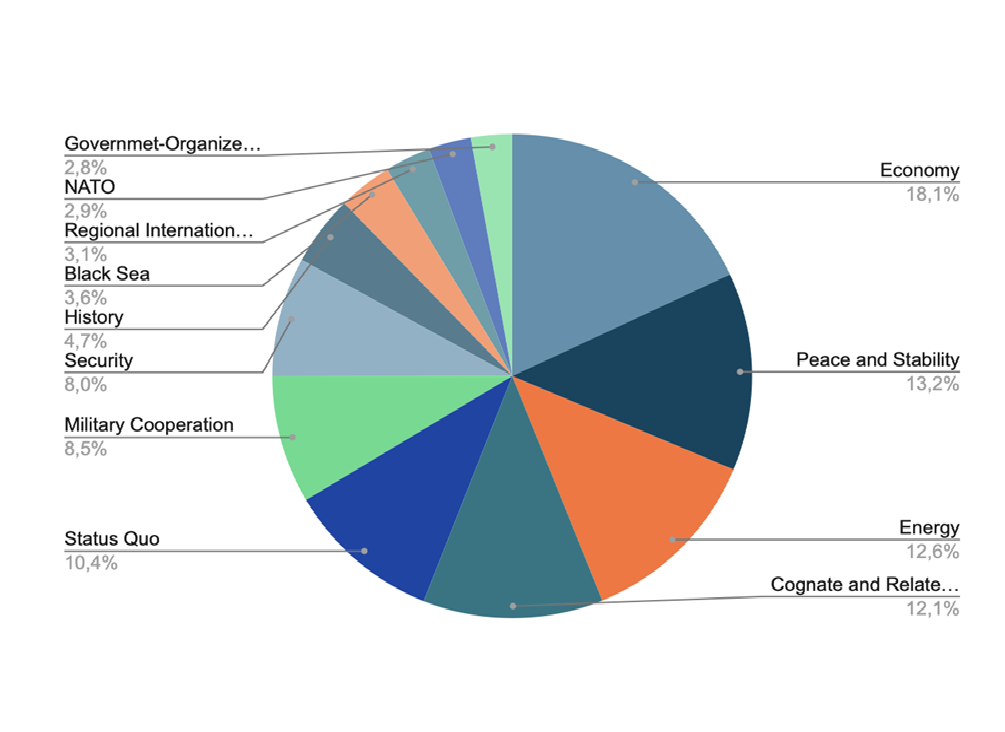

Table 1: The results of the content analysis (in %)

The content analysis method was used in this study to analyse Turkish political elites’ discourses. The statements made by Turkish political elites (Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, President, and Presidential Spokesperson) during their visits to the Black Sea countries (Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia) between May 2014 and December 2023 were subjected to content analysis within the framework of region-building processes. For this purpose, a total of 42 visits by Turkish political elites to the Black Sea Region and 49 documents containing transcripts of official statements made in this context were used in the selected period of time. The limitations of the study include the statements made by the political elites during their visits to the Black Sea littoral states during the period under review. However, the meetings that took place in the framework of the Astana process, initiated to resolve the Syrian conflict, were not analysed, as they did not concern the Black Sea Region. MAXQDA 24 was the software used for our content analysis. We uploaded transcriptions of the Turkish political elites’ statements to this program, and we found relevant data as an output of the content analysis. We analysed the data that we obtained to test our research questions.

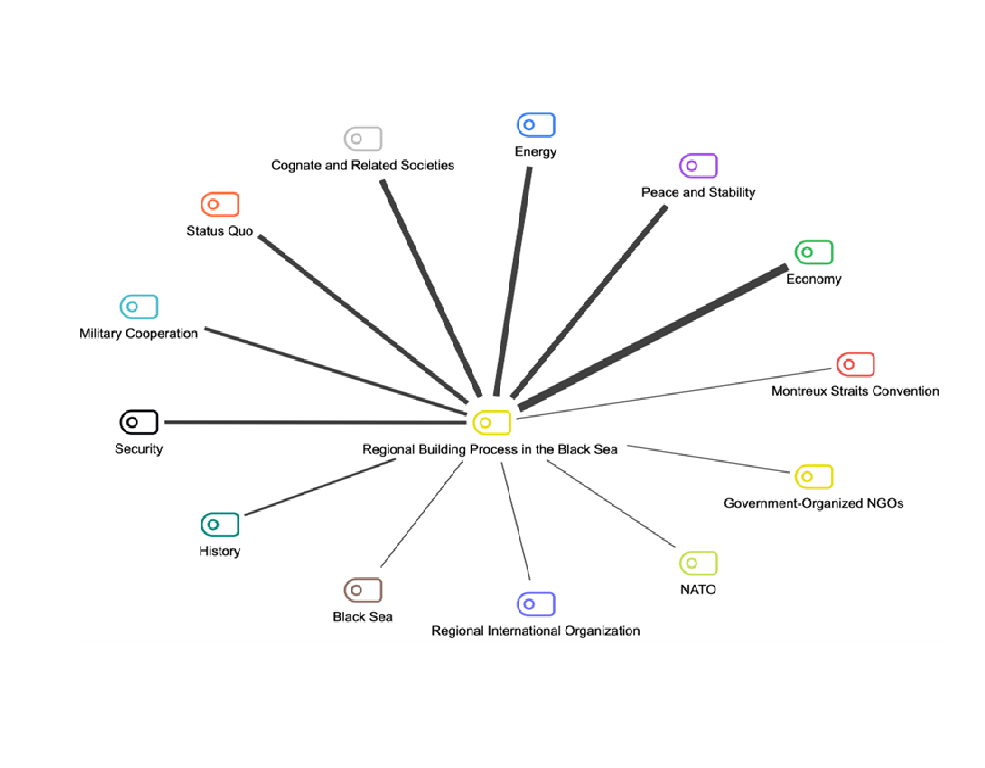

Figure 1: Frequencies of sub-codes (MAXQDA-codes-sub-codes)

The content analysis consists of one code and thirteen sub-codes. The code was determined as “region-building process in the Black Sea,” which is the main reference point of the article. The sub-codes were selected in the context of the stages of region-building, which we have reinterpreted in our article with reference to the first and second waves of regionalism.

When creating the sub-codes, words that affect the sub-codes were considered. In this context, “trade” and “free trade” were taken into account in the “economy” sub-code. “Turkish Stream,” “Akkuyu nuclear power plant,” and “natural gas” were added to the “energy” sub-code. “Crimean Tatars,” “Meskhetians,” and “Gagauz” were included in the sub-code “cognate and related societies.” “territorial integrity,” “border security,” and “sovereignty” were covered in the sub-code “status quo.” In the sub-code “military cooperation,” “SIHA,” “UAV,” “Bayraktar,” “S-400,” “military,” “defence agreements,” and “security” were used. In addition, the sub-code “history” contains the Ottoman Empire, Turkish states and rulers, the Republican period, and former rulers. In addition, organisations such as the BSEC, BLACKSEAFOR, Black Sea Harmony, and the Black Sea Grain Initiative have been evaluated in the sub-code “regional international organisations.” Finally, the sub-code “government-organised NGOs” includes institutions, such as TIKA, YTB, TMF, YEI, and so on, that are active in the region.

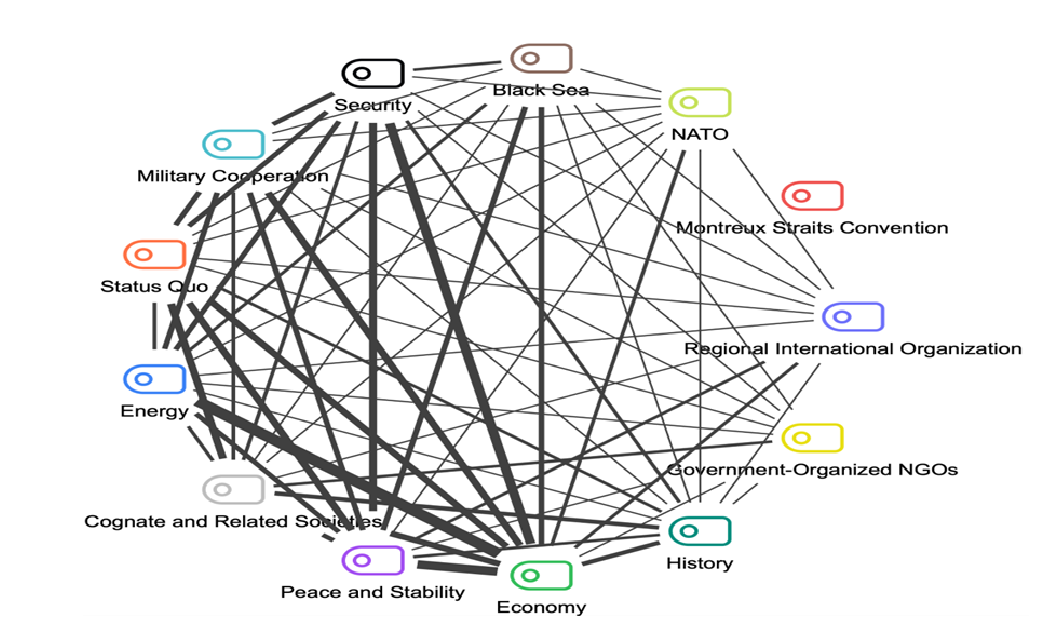

Figure 2: Interaction of sub-codes

In Figure 2, the interrelations between the sub-codes are shown with lines. The frequency of interaction of the sub-codes can be analysed according to the lines shown in the figure.

Sharing the same norms, values, and institutions is important for the region-building process, but the region’s ability to interact within the international social structure is another important aspect of the process.[xxi] Türkiye’s role in the Black Sea Region-building process is analysed under five stages. In this study, the following stages has been proposed. They are inspired by the literature on region-building processes and regional security. The first stage is the identification of the Black Sea Region; the second stage involves the historical roots of political relations in the region; the third stage is the establishment of regional cooperation, taking into account the concept of regional international society; the fourth stage is the geo-psychological aspect of the Black Sea Region; and lastly, the fifth stage has been formulated along with Buzan’s argument that the “security” factor is an effective determinant in the region-building process, and that the regions are shaped in line with security concerns. Therefore, the last stage will concentrate on the construction of regional security.

2.1. Identification of the region

In this study, the first wave of regional studies is updated with the second wave of regional studies, and a new understanding of the region-building process is proposed to evaluate Türkiye’s process of Black Sea Region-building. First and second wave studies have many common points in their approaches to identify the “region.” Hettne’s identification of geographic and environmental borders of the region is parallel to Costa Buranelli’s emphasis on the proximity of states for regionalisation.

Costa Buranelli suggests that a region should be viewed as a separate entity within the world, rather than being equated with the world itself.[xxii] Additionally, proximity between units within the region is important as it allows for interaction and interdependence.[xxiii] The Black Sea Region is located at the junction point of east-west and north-south. According to Hettne,[xxiv] “regional space” should not be viewed solely as a result of geographical factors, but rather as an essential component of a functioning society. Territory is an important aspect of a society’s identity and functioning, and cannot be ignored.[xxv] In this context, the territory on which the society lives should be considered, but the cultural, political, and security elements that construct the society should not be ignored.

Geopolitically, if we try to identify the Black Sea Region, various descriptions emerge due to historical and political factors.[xxvi] The Black Sea is located at a strategic position, as it is an extension of the Balkans and lies at the intersection of the Gulf, East Mediterranean, and Europe.[xxvii] It was referred to as the “inhospitable sea” in ancient Greek times due to conflicts between enemy tribes in the sea and on its shores.[xxviii] Two different approaches are used to identify the Black Sea Region geographically, in narrow and wide senses. When looking at the Black Sea Region from a narrow perspective, it includes Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Ukraine, Russia, and Türkiye. To provide a wider perspective, the region includes the location where the Danube, Dnieper, and Don rivers converge and subsequently discharge into the sea. The “Greater Black Sea” concept emerged not on the basis of geography but as a result of struggle between great powers on politics, economics, and security.[xxix] The Black Sea is not an inland lake, but a gateway to the Mediterranean and a bridge between the Balkans and the Caucasus; the countries bordering the Black Sea (Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Russia, Türkiye, and Ukraine) and the neighbouring countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Greece, and Moldova) are included in regions such as Southeast Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean.[xxx] The Black Sea is more of a political region, and not just a geographical region.[xxxi] Therefore, political interaction of the proximate units is important in the case of the Black Sea Region.

When we examined the discourse of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the President of Türkiye, since 2014 to understand how the identification of the region reflects on official discourses, we found that just before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there were remarkable statements made. On the 22nd of February 2022, he said, “Since we are a Black Sea country, many packages of measures must be established… We cannot leave aside the responsibilities that being a Black Sea country imposes on us.”[xxxii] In his speech, he underlined that Türkiye is a “Black Sea Country.” According to the official website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Türkiye, the world is divided into ten regions (including Europe, the Balkans, South Caucasia, the Middle East and Central Asia, South Asia, Sub-Sahara, North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Asia-Pacific).[xxxiii] It is interesting to note that there is no mention of a specific regional classification for the Black Sea. For example, when we look at the regional classification of the countries bordering the Black Sea, Georgia is defined as being in the South Caucasus region, while Romania is defined as being in the Balkan region, and Bulgaria is included in both Europe and the Balkans.[xxxiv] In light of this information, Türkiye does not provide a clear definition of the Black Sea Region, though the first stage of region formation is to highlight the geography. The content analysis shows that the sub-code “Black Sea” is not highly (3.6%) mentioned in political elites’ discourses (see, Table 1). In addition, this code highly interacted with the sub-code “economy” (see, Figure 2). This means that the term Black Sea as a region was not stressed in the discourse too much. However, economic bilateral relations between Black Sea countries and Türkiye are stressed as more important in the discourse.

2.2. The establishment of historical and political relations

After the identification of the borders of the region, the second stage stipulates the formation of historical relations among main actors in the region. Hettne and Söderbaum perceive regions as transnational communities, taking into account culture and history rather than state systems.[xxxv]

The Black Sea is a geopolitically important region, and throughout history, it has been the target of great powers who have had a desire for control. The Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and Russian Empires tried to establish dominance over the Black Sea, which was ruled by the Ottoman Empire for three centuries starting from the 15th century.[xxxvi] During the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror, Crimea was seen as an important safety area of Black Sea trade.[xxxvii] The acquisition of Crimea ensured the security of the northern region and allowed the Ottoman Empire to pursue an active foreign policy against the countries of the region. In the 18th century, the rivalry between Ottoman Empire-Russia was escalated by Catherine II due to the policy of accessing the warm waters.[xxxviii] The invasion of Crimea in this century led to the forced migration of Crimean Tatars as part of the Russification policy.[xxxix] After the invasion of Crimea, Russia became the power controlling trade in the Black Sea Region and regarded the security of the Black Sea as an essential condition for its own safety. To achieve their security objective, the Russians fought to dominate the northern Black Sea from the Sea of Azov to the Crimea.[xl] The Ottoman Empire considered the Black Sea as its own “Ottoman lake”[xli] until the Kücük Kaynarca Treaty, and now Türkiye, as its successor state, is one of the biggest countries that have access to the Black Sea.

In the Soviet era, Black Sea countries were a part of the USSR, excluding Türkiye. During Stalin’s administration, cognate and related societies, in particular the Crimean Tatars, were forced to emigrate from the USSR because they were accused of having collaborated with Nazi Germany. This oppressive policy towards these cognate and related societies continued until the 1980s. During the Cold War, Türkiye opted to be cautious about its relations in the Black Sea Region with these societies. The policies of glasnost and perestroika adopted by Mikhail Gorbachev after he came to power improved the relations of Türkiye with cognate and related societies. Türkiye’s foreign policy towards the Turkic Republics changed after the collapse of the USSR, leading to closer relations and cultural collaborations with these Republics in the post-communist period. In the context of the Black Sea Region, Türkiye also improved relations with cognate and related societies, especially with Crimeans in the post-Cold War period.

When we analysed Turkish political elites’ discourses in the content analysis, we found that the “history” sub-code (4.6%) has a lower frequency (see, Table 1). In the imperial era, as we mentioned above, there were two dominant powers, Russia and the Ottoman Empire, in the Black Sea Region; however, they had risen and fall relations until the collapse of tsarist Russia. During the Cold War period, Türkiye and the USSR belonged to different blocks, therefore they had minimal relations. Turkish political elites prefer not to stress “history” in their discourses during their regional visits because they do not want to emphasise conflictual or distant historical relations with Russia. In addition, in the post-Cold War period, there are newly independent countries, and there are different dynamics in relations.

However, when we look at the content analysis, there is a relatively high interaction between the “history” sub-code and the “cognate and related societies” and “peace and stability” sub-codes (see, Figure 2). The relationship between the sub-codes supports that Türkiye prefers to use a discourse based on friendship and consensus in region-building processes. As the former Minister of National Defence, Hulusi Akar’s statements are parallel to the findings of our content analysis. He stated, “Throughout our history, we have always respected the sovereignty, borders, and territorial integrity of all countries, especially our neighbours.”[xlii]

2.3. Establishment of regional cooperation

When it comes to the third stage in the region-building process, Hettne predicts that regional structure is needed to achieve an organised and coordinated cooperation between the existing main elements in the region.[xliii] The current perspective in regional studies suggests that the distinctive institutions established at the regional level are what characterise a regional international society in contrast to the global level.[xliv] Therefore, the establishment of regional cooperations and their institutionalisation is essential for the regionalisation process.

In this context, Türkiye plays a key role in the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), the Black Sea Naval Cooperation Task Group (BLACKSEAFOR), the Black Sea Harmony Operation, and the Black Sea Grain Initiative to enhance regional cooperation in the Black Sea. BSEC was established in 1992, although the idea of its creation dates back to the pre-Soviet period. This initiative aims to ensure regional security through the development of economic, trade, and political relations between the states of the region.[xlv] From the past to the present, BSEC is an organisation that aims to integrate into the global economy through a regional strategy based on interdependence and the use of natural synergies. Beyond an intergovernmental dimension, BSEC operates through the institutions it has established, meeting its material needs and creating a legal infrastructure. As a result, it has acquired an institutional identity and become a regional economic organisation.[xlvi] The BSEC has been slow in achieving its desired goals of regional political stability and economic cooperation in the region, which is clear given the existence of problems between Russia and Georgia and Russia and Ukraine. Despite the conflict and war in the Black Sea Region, Türkiye has always endeavoured to maintain and develop economic relations.[xlvii] This attitude is also evident in the discourse of former foreign and economic ministers.[xlviii] Türkiye was not among the countries that imposed economic sanctions on Russia during the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. In 2022, during the war between Ukraine and Russia, Türkiye adopted a different stance from European states. While Türkiye only imposed UN sanctions, European states also imposed more severe economic sanctions. Economic and energy dependence on Russia and the presence of direct borders are the main reasons for this decision. Our content analysis reveals that although BSEC is structurally related to the sub-codes “economy” (18.1%) and “regional international organisations” (3.1%) (see, Table 1), the use of both sub-codes together in political discourse is low (see, Figure 2).

The second regional organisation is BLACKSEAFOR, established in 2001.[xlix] Its activities include search and rescue, mine clearance, humanitarian assistance, and the exchange of information on illegal maritime activities through the establishment of a Black Sea Border Control Centre with a supplementary agreement.[l] Another regional organisation launched by Türkiye was Operation Black Sea Harmony in 2004, which aimed to counter terrorism in the region under UN auspices and share information with NATO. Russia, Ukraine, and Romania participated in the operation, while Bulgaria and Georgia asked to join.[li] Through BLACKSEAFOR and Operation Black Sea Harmony, Türkiye sought to transfer the experience in the economic cooperation within the framework of BSEC to the military field. However, the membership of the Black Sea littoral states in both organisations has been negatively affected by the conflicts that began with the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008.

If we look at the content analysis, “regional international organisation” (3.1%) has relatively less frequency (see, Table 1). Türkiye wanted to ensure maritime security in its territorial waters and in the Black Sea Region. If we look at the interaction between the “regional international organisation” sub-code, it has relatively less interaction with the sub-code “military cooperation” (see, Figure 2). The discourses revealed that “military cooperation” was intended to be carried out through bilateral and trilateral cooperation with countries in the region rather than on the basis of a regional international organisation.

Looking at regional international organisations in the Black Sea Region, a number of institutions were established in the aftermath of the Russia-Ukraine war that began in 2022, in which Türkiye played a leading role. The first of these was the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which aimed to export grain to world markets.[lii] According to the agreement, cargo ships using the food corridor would be inspected at points to be established by Türkiye with the participation of Russia.[liii] The second institution is the trilateral mechanism, which organises mine-clearance activities involving Türkiye, Romania, and Bulgaria, as the Russian-Ukrainian war has prevented all littoral states from participating in BLACKSEAFOR mine-clearance activities.[liv] These initiatives show that despite the conflicts in the Black Sea Region, Türkiye continues to act within a peaceful framework in accordance with international law.

The content analysis shows a greater interaction of the “regional international organisation” sub-code with “peace and stability” and “economy” in comparison with other sub-codes (see, Figure 2). For instance, the Black Sea Grain Initiative, an internationally established framework for the region, aims to enhance economic relations while also promoting regional peace and stability. Therefore, the Black Sea Grain Initiative has an economic dimension in addition to its humanitarian aid dimension. In addition to this, mine clearance and search operations in the region are directly linked to the discourse of constructing regional security. Thus, we can infer that political elites’ discourses are congruent with their policies.

2.4. The geo-psychological aspect of region

The geo-psychological aspect of regionness is similar to Hettne’s last stage of creating a common culture and identity in contribution to civil society. The people who live in regions accept their norms, values, and rules.[lv] The geo-psychological aspect of a region[lvi] is related to the ideational, social, normative, and identity-related relations in the region.[lvii] The interaction between units in a regional international society is essential for the geo-psychological aspect of the region. It is because of this that government-organised NGOs have a crucial role in the regional identity-building process.

Hettne put region-building stages in the context of a new regionalism theory to explain the evolution of regional identity.[lviii] According to this theory, the stages (regional space, regional complex, regional society, regional community, and regional state)[lix] represent different aspects of regional integration and development, and each builds upon the previous stage.[lx] Regional complex is about the interaction of human groups and cultures.[lxi] The development of society at a regional level is crucial as it involves the exchange and cooperation between governmental and non-governmental entities through economic, political, and cultural means. Such communication and interaction between various actors are vital for societal progress.[lxii] After undergoing these processes, the regional community transforms into a dynamic entity that possesses a unique identity, either formal or informal institutional capabilities, legitimacy, and a structured decision-making system. It interacts with a regional civil society that is more or less responsive and extends beyond the traditional boundaries of nation-states.[lxiii] And the last stage is the removal of different identities, actors, and decision-makers in the region.

In terms of the geo-psychological aspect of regionness, interaction between different social units is important for the multidimensional structure of regionalisation. Regionalisation is not limited to interstate relations because of the impact of globalisation, which caused interdependence between government-organised NGOs, multinational corporations, and civil society to increase. Therefore, in the region-building process, all these actors are essential.[lxiv] Hettne and Söderbaum put forward that transnational regions provide security and prosperity because of the insecure and destructive nature of the nation-state. Therefore, they underline the region-building process that is less state-centred and includes non-state actors and transnational powers. They argue that the formation of a region does not necessarily require geographical proximity, but rather the existence of a regionalism perspective (e.g., the EU).[lxv]

In the case of Türkiye’s role in the region-building process in the Black Sea, we can observe that Türkiye seeks to build a common culture, identity, and norms among ethnic kinship communities living in the Black Sea Region through various government-organised NGOs. The USSR and Türkiye belonged to different poles during the Cold War. As a result, government-organised NGOs were not able to operate effectively in the USSR era to build a common culture, identity, and norms among cognate and related societies living in the Black Sea Region. Türkiye started new initiatives to improve relations with newly formed independent states with the disintegration of the USSR after the Cold War. In the region, some activities were carried out, such as the “1,000 Houses” initiative.[lxvi] In order to support these new initiatives, some cooperation-improving institutions, such as the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), Yunus Emre Institute (YEI), Presidency for Turks Abroad and Relatives Communities (YTB), and the Turkish Maarif Foundation (TMF) have appeared in Türkiye’s Black Sea Region-building processes.

TIKA was established in 1992 to improve cooperation with the territories with which Türkiye has cultural and historical ties. TIKA tried to increase cooperation in these regions with educational, cultural, and infrastructure studies. Both economic and technical aids were provided, especially in the Black Sea Region, to improve communication, transportation, and construction infrastructure. In this context, and with the Town-Twinning Project, official buildings were built, and grants and training were given to cultural, social, and media (energy and war correspondent) organisations.[lxvii] Another government-organised NGO which contributes to Türkiye’s cooperation with other countries is the YEI, which was established in 2007. The institute aimed to introduce the language, history, culture, and art of Türkiye to the world, and for this purpose, it focused on various teaching activities.[lxviii] Also, YTB was established in 2010 and enabled the cooperation of Turkish cognates and related societies living abroad. Its first aim was to look out for these societies all over the world.[lxix] For this purpose, the organisation conducted activities to enhance the relations between Türkiye and communities in the Black Sea Region, which Türkiye has historical, cultural, and social ties with.[lxx] Lastly, the TMF was established in order to improve Türkiye’s cultural and civilisation interaction. The foundation carried out activities in international fields such as education, publication, scholarship, and accommodation. It was established in 2016 and shares the unique authority, along with the Ministry of Education, to open an overseas educational institution. In this context, it pursues the goal of carrying out activities at every stage of education, from preschool to higher education, in the region. The TMF carried out activities such as opening culture and study centres, producing publications in the field of education, organising conferences and workshops, and providing books, notebooks, computers, and clothes via scholarships.[lxxi] All of the institutions mentioned above have played a considerable role in region-building processes by creating a civil society in the Black Sea Region. Thanks to these institutions, cooperation has improved, and relations could be established with ethnic Turkish societies in the region.

Thus, through government-organised NGOs, Türkiye is taking initiatives to rebuild the Black Sea region and support communities affected by conflict.[lxxii] In Table 1, in the context of Türkiye’s role in the Black Sea Region-building process, Turkish political elites emphasise the sub-code of “economy” (18.1%) more than “cognate and related societies” (12.1%). This is an indication of the importance Türkiye attaches to economic cooperation in the region-building process. The “economy” sub-code is related to “cognate and related societies” (see, Figure 2). There is a relatively high interaction between these codes because Türkiye is giving economic support to develop infrastructure in cognate and related societies in the Black Sea Region. However, these initiatives are implemented with the intention of protecting the rights of cognate and related societies and preserving the values, traditions, and culture of the Black Sea Region, rather than building a common Black Sea identity. In these endeavours, government-organised NGOs have made a positive contribution. With our content analysis, we can see that “government-organised NGOs” (2.8%) appears as the lowest sub-code (see, Table 1), and it has a high level of interaction with the sub-code “cognate and related societies” (see, Figure 2). This shows that Turkish political elites support cognate and related societies in the process of developing the Black Sea Region.

2.5. Construction of regional security

The interaction of units in the region and the socialisation process would be more functional in a stable environment. Economic relations between the countries in the region would create interdependency, which would, in turn, aid in the creation of a regional security community.[lxxiii] In order to focus on creating a regional security community in the region-building process, it is useful to address the RSCT, which was put forward by Buzan and Wæver. They defined “regional security complex” as the geographical areas which face common security challenges.[lxxiv] Buzan divided the world into regional security complexes, thus emphasising the necessity of cooperation between states in facing international security problems.[lxxv] In a security complex, states are interdependent due to their concerns about certain security issues, and there should be a mechanism to balance the powers in the region.[lxxvi] The formation of a regional security complex signifies an ongoing growth of relationships, both positive and negative, among various groups of individuals, as well as the influence of different cultures. These relationships and influences extend beyond local boundaries and affect the region as a whole.[lxxvii] According to Buzan, ideal types of regional security complexes are dependent on whether security interdependence is defined more by amity or more by enmity. These ideal types are “conflict formations,” “security regimes,” and “security communities.”[lxxviii]

Türkiye’s foreign policy preferences indicate that it aims to achieve the third ideal type of RSC in the Black Sea Region, in which regional states no longer use force against each other, but create security communities through cooperation and convergence. In this context, there are three important factors in Türkiye’s role in constructing regional security in the Black Sea Region.

The first determining factor is the Montreux Convention, which was signed at the beginning of the Republican era. This convention stipulates that Türkiye has the sole authority for the armament of the Turkish Straits (Straits of Çanakkale, the Bosphorus, and Marmara Sea) without the need for any commission. In addition, the treaty distinguishes between Black Sea littoral states and non-Black Sea littoral states and regulates the passage of warships and aircraft from these states. Under the terms of the treaty, Türkiye has the authority to decide on warships in the event of war or the threat of war. In peacetime, the warships of the Black Sea littoral states cannot exceed a certain capacity, and under the condition of prior notification, warships can stay in the Black Sea for an unlimited period of time. Warships of the countries which do not have coasts on the Black Sea are subject to certain restrictions. Aircraft carriers, submarines, and warships of those countries will not be able to pass through the Turkish Straits. During times of war in which Türkiye is not taking any part, the warships of countries at war cannot pass through any of the Turkish Straits. However, there are certain exceptional circumstances. According to the contract, warships have the right to pass through the Turkish Straits if they want to return to the mooring port, or in cases where they will apply compelling rules on behalf of the League of Nations, which only apply on the condition that Türkiye is a party in an aid agreement. Permission for passage of military aircraft is left entirely to Türkiye’s discretion.[lxxix] As can be seen, the treaty gives Türkiye important powers over the security of the Black Sea Region. Meanwhile, the limitation of warships also plays an important role for peace and stability in the region. Following the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Akar stated, “We have implemented Articles 19, 20, and 21 of the Montreux Convention until today and will continue to do so in the future; this is beneficial for all littoral states and regulates the entry and exit of other countries.”[lxxx] The Montreux Convention is binding for ensuring security in the Black Sea Region. Based on official visits by Turkish political elites to the Black Sea countries, the content analysis shows that “Montreux Straits Convention” (1<%) is not mentioned in the discourses, which focus more on the concept of the “status quo” (10.4%) (see, Table 1). This can be interpreted as Turkish political elites preferring not to overemphasise their regulatory powers under the convention.

The second factor that is important for Türkiye’s role in the security of the Black Sea Region is the issue of energy, which is economically dependent on the geo-strategic position of the Black Sea. In the content analysis, the sub-code “energy” (12.6%) has the third highest frequency, which shows that political elites emphasise the importance of energy in the political discourse (see, Table 1). As the Black Sea is an energy corridor, there are important nodes in the construction of regional security, such as the Southern Gas Corridor and Turkish Stream. Energy trade, especially through transmission lines, ensures security of supply and demand between supplier and consumer countries. In 2022, the war between Russia and Ukraine meant an energy crisis for the European region. The European region, which is dependent on energy resources in the Black Sea (especially Russia), began looking for new alternative routes due to the situation in Ukraine. The fact that Russia is taking a similar stance[lxxxi] raises the possibility of Türkiye strengthening its role as a transit country and becoming a natural gas distribution centre. Türkiye is seeking[lxxxii] to take a key position in energy security in Europe and the Black Sea Region. If Türkiye becomes an energy hub for Europe, it will contribute to maintaining its multidimensional foreign policy in the region. Natural gas, which was discovered in the Black Sea in recent years, has given Türkiye a chance to become an energy supplier and has made room for foreign policy development since it is both a consumer and a transit country. By implementing policies in this direction, Türkiye focuses on being a hub for energy.[lxxxiii] These developments show that Türkiye has a key position in terms of ensuring energy security in the Black Sea regional security-building process. The content analysis shows that the interactions between the “economy” and “energy” sub-codes are the highest in the discourse (see, Figure 2). This is because energy is included in the region-building process in addition to the economy. While Türkiye provides economic gain and interdependence with energy, it also considers military cooperation and security. Looking at the relationship between the sub-codes, we also see that there is a close interaction between “military cooperation,” “security,” and “energy” (see, Figure 2). Energy security is crucial, and it is mostly related to stability in the region. Therefore, military cooperation is essential to ensure stability in the region.

Thirdly, it can be suggested that Türkiye’s persistence to implement a policy to maintain the “status quo” (10.4%) in the Black Sea Region-building process has an important influence on regional security-building (see, Table 1). In order to maintain peace and stability in the Black Sea’s security, Türkiye has sought to increase mutual cooperation with NATO and the EU. In 2019, Çavuşoğlu stated, “We are a NATO member, and we support and contribute to the decisions taken by NATO. We do not want the Black Sea to be a sea of tensions. On the contrary, we want it to be a sea of peace, tranquillity, and stability.”[lxxxiv] This declaration presents the Turkish stance in the Black Sea security-building process as a NATO member with a peaceful approach. One of Türkiye’s foreign policy approaches is mediation. The “status quo” sub-code has a weak interaction with the “NATO” and “Black Sea” sub-codes, but on the other hand, it has a higher interaction with the sub-code “economy” (see, Figure 2). We interpret this to mean that Turkish political elites do not relate their discourses about keeping the status quo in the Black Sea Region to NATO directly. According to the data that we provide with our content analysis, it seems that economy is a primary condition for keeping the status quo, so political elites emphasise economy in foreign policy discourse. Similarly, the “security” sub-code has a high interaction with “economy” (see, Figure 2). This also shows that Türkiye has a foreign policy based on economic interests.

Türkiye’s foreign policy preferences suggest a commitment to realising the third ideal type of RSC. In this model, regional states seek to foster cooperation and convergence rather than resorting to force, with the ultimate goal of creating “security communities.” With this model in mind, the Montreux Convention and energy resources are crucial for ensuring security in the Black Sea Region. Türkiye seeks to promote coexistence and cooperation to constrain mutual securitisation processes and maintain the status quo in the Black Sea, as this is the main driver of its foreign policy in the region. Its ultimate goal is to create a “security community” based on cooperation.

Since 2014, the tensions between Russia and Ukraine, two important countries of the Black Sea Region, continue to negatively affect the processes of regional building. In this context, we conducted a content analysis of Türkiye’s priorities and policies in the region using the stages suggested by the theoretical literature on regionalism. We argue that the process of security-building is the backbone of creating a “regional international society.”

Looking at the content analysis stages one by one in terms of Türkiye’s role, firstly, it can be seen that Turkish political elites do not attach too much importance to the identification/naming of the region in their discourses. However, the interaction between sub-codes shows that economic bilateral relations between Black Sea countries and Türkiye are more important. Secondly, in terms of historical relations in the Black Sea Region, Türkiye does not emphasise the Ottoman period because it believes that the presence of conflicting historical relations in the region would have a negative impact on the regional building process, and it can be said that it chooses the path of stability by adopting a conciliatory and peaceful attitude towards the states of the region. Thirdly, Türkiye contributed to the formation of regional cooperation through the BSEC, the BLACKSEAFOR, and the Black Sea Harmony Operation. Türkiye aims to create interdependence by developing economic relations with the states of the region through the BSEC despite wars and conflicts (2014-2023) having a negative impact on the regional building processes. Türkiye is making efforts to ensure that economic relations will continue in this environment. In addition to Türkiye’s maritime security initiative, BLACKSEAFOR, the country also stands as a founding member of the Black Sea Harmony Operation, receiving NATO military support. However, these initiatives have been negatively affected by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It should be noted that besides these initiatives, Türkiye, with its authorisations derived from the Montreux Convention, also holds a significant role in maritime security in the Black Sea Region. Another significant attempt of Türkiye is the Black Sea Grain Initiative, set up under Turkish leadership to find a solution to the grain crisis caused by the Russia-Ukraine war. This initiative has emerged as another institution with the potential to increase regional cooperation after the war. Mine cleaning and mine search activities are also Turkish initiatives meant to improve security and stability in the region. Fourthly, in the context of the geo-psychological aspect of the region, Türkiye, along with government-organised NGOs such as TIKA, YTB, YEI, and the TMF, plays a considerable role in the construction of a regional identity by establishing a civil society in the Black Sea Region. Türkiye is thus giving economic support and aid for infrastructure to cognate and related societies in the Black Sea countries. Through these institutions, Türkiye can cooperate with cognate and related societies in the region, and with government-organised NGOs, Türkiye has made a positive contribution to the Black Sea Region-building process. Fifthly, in the context of building regional security in the Black Sea, Türkiye has implemented policies aimed at maintaining regional peace and stability. At this stage, Türkiye’s role in regional security is discussed in terms of three factors: the Montreux Convention, energy, and maintaining the status quo. On the basis of the Montreux Convention, Türkiye seeks to build coexistence and cooperation in order to limit mutual securitisation processes by maintaining the status quo in the Black Sea and creating an economic security community through energy.

In a stable region, the establishment of a regional security community becomes more feasible, as economic interdependence among countries fosters cooperation. However, it is important to recognize the challenges of creating a regional international society in a conflict zone, where the lack of shared norms and values hinders the development of economic relations. Thus, the construction of security and the resolution of conflicts are essential prerequisites for the region-building process. Furthermore, the formation of an economic community can reinforce political and cultural ties, thereby facilitating the development of a regional international society. In the Black Sea Region, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has created a situation more difficult for the Black Sea regional building process than the illegal annexation of Crimea and has had a direct negative impact on the Black Sea regional building process. Despite this, Türkiye wants to play a mediating role to end the war. In this context, both parties in the war have emphasised Türkiye’s “facilitating role” in negotiations, and Ukraine asked Türkiye to be a “guarantor country” in case of a peace agreement in 2022. Türkiye’s status as a guarantor country implies that it will play an important role in the post-war security-building process in the region. In 2022, Türkiye worked for lasting peace by being open to dialogue with both countries and bringing the parties together through the Antalya Diplomatic Forum. Türkiye played a mediating role by creating a humanitarian aid corridor, balancing relations with both sides and trying to ensure that the civilian population remains as unaffected as possible by political tensions. In July 2023, Russia withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative; however, Türkiye continues to establish alternative mechanisms to restart grain diplomacy involving Russia, Türkiye, Ukraine, and the UN.

Consequently, we believe that the security construction process is the backbone of the creation of a “regional international society.” Yet, given the conflicts in the region since 2014, the lack of stability dims the hope of creating a regional society.

Notes

[i] David Lake and Patrick Morgan, Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 26.

[ii] Björn Hettne and Fredrik Söderbaum, “Theorising the Rise of Regionness,” New Political Economy 5, no. 3 (2000): 457-472.

[iii] Lake and Morgan, Regional Orders, 26.

[iv] Filippo Costa Buranelli and Aliya Tskhay, “Regionalism,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, ed. Renee Marlin Bennett (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 5.

[v] Filippo Costa Buranelli, “The English School and Regional International Societies: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections,” in Regions in International Society, eds. Ales Karmazin et al. (Brno: MUNI Press, 2014), 26-27.

[vi] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 461.

[vii] Amitav Acharya, “Comparative Regionalism: A Field Whose Time has Come?” The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 47, no.1 (2012): 8.

[viii] Andrew Hurrell, “Regionalism in Theoretical Perspective,” in Regionalism in World Politics: Regional Organization and International Ordered, eds. Louise Fawcett and Andrew Hurrell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 39-40.

[ix] Costa Buranelli, “The English School,” 26-30.

[x] Ibid., 31.

[xi] Amitav Acharya, “How Ideas Spread. Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism,” International Organization 58, no. 2 (2004): 207.

[xii] Barry Buzan and Ana Gonzalez Pelaez, International Society and the Middle East: English School Theory at the Regional Level (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 33-34, 241-242.

[xiii] Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[xiv] Barry Buzan, “Regional Security Complex Theory in the Post-Cold War World,” in Theories of New Regionalism, eds. Fredrik Söderbaum and Timothy M. Shaw (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 157-159.

[xv] See, Panagiota Manoli, “Where is Black Sea Regionalism Heading?” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 323-339; Paskal Zhelev, Building a Closer Black Sea: Promoting Trade and Economic Interdependence (Munich: Middle East Institute’s Frontier Europe Initiative, August 2021), 1-11; Mustafa Aydın, “Regional Cooperation in the Black Sea and the Role of Institutions,” PERCEPTIONS: Journal of International Affairs 10, no. 3 (2005): 57-83.

[xvi] See, Felix Ciută, “Region? Why Region? Security, Hermeneutics, and the Making of the Black Sea Region,” Geopolitics 13, no. 1 (2008): 120-147; Panagiota Manoli, The Dynamics of Black Sea Subregionalism (London: Routledge, 2012); Dimitrios Triantaphyllou, “Filter through Region-Building in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea Regions,” Hellenic Studies 14, no. 1 (2006): 31-40; Diana Rusu, “Regionalization in the Black Sea Area: A Comparative Study,” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 11, no. 2 (2011): 47-65; Fabrizio Tassinari, “Region-Building as Trust-Building: the EU’s Faltering Involvement in the Black Sea Region,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 11, no. 3 (2011): 227-239.

[xvii] See, Oleksandr Pavliuk and Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze, The Black Sea Region: Cooperation and Security Building (London and New York: Routledge, 2004); Dimitrios Triantaphyllou, The Security Context in the Black Sea Region (London: Routledge, 2013); Özgür Özdamar, “Security and Military Balance in the Black Sea Region,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 341-359; Oksana Antonenko, “Towards a Comprehensive Regional Security Framework in the Black Sea Region After the Russia-Georgia War,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9, no. 3 (2009) 259-269; Mukhtar Hajizada, “Challenges and Opportunities for Establishing a Security Community in the Wider Black Sea Area,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 18, no. 4 (2018): 529-548; Yannis Tsantoulis, The Geopolitics of Region Building in the Black Sea: A Critical Examination (New York: Routledge, 2021); Hasret Çomak et al, Karadeniz Jeopolitiği (Istanbul: Beta Yayınevi, 2018).

[xviii] See, Sophia Petriashvili, “Where is the Black Sea Region in Turkey’s Foreign Policy?,” Turkish Policy Quarterly 14, no. 3 (2006): 105-112; Gareth M. Winrow, “Turkey and the Greater Black Sea Region,” in Contentious Issues of Security and the Future of Turkey, ed. Nursin Atesoglu Guney (London: Ashgate, 2007), 121-136; Mustafa Aydın, “Geographical Blessing Versus Geopolitical Curse: Great Power Security Agendas for the Black Sea Region and a Turkish Alternative,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9, no. 3 (2009): 271-285; Duygu Bazoğlu Sezer, “Turkey in the New Security Environment in the Balkan and Black Sea Region,” in Turkey Between East and West, ed. Vojtech Mastny (New York: Routledge, 1996), 70-96.

[xix] Tim Dunne, “New Thinking on International Society,” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 3, no. 2 (2001): 235.

[xx] Filippo Costa Buranelli, “Do you Know What I Mean? ‘Not Exactly’: English School, Global International Society, and the Polysemy of Institutions,” Global Discourse 5, no. 3 (2015): 500-501.

[xxi] Barry Buzan, “How Regions were Made, and the Legacies for World Politics: An English School Reconnaissance,” in International Relations Theory and Regional Transformation, ed. T.V. Paul (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 22-46.

[xxii] Costa Buranelli, “The English School,” 26.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] According to their perspective on new regionalism theory, there are five stages or dimensions of regionness. These include the regional space, regional complex, regional society, regional community, and regional state. See, Björn Hettne, “The New Regionalism: Implications for Development and Peace,” in The New Regionalism: Implications for Global Development and International Security, eds. Björn Hettne, Andras Inotai, and Osvaldo Sunkel (Forssan Kirjapaino Oy: UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research, 1994), 7.

[xxv] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 462.

[xxvi] Peter Jay, “Regionalism as Geopolitics,” Foreign Affairs 58, no. 3 (1979): 485-514.

[xxvii] Oral Sander, Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası (Istanbul: İmge Yayınları, 1998), 197.

[xxviii] Naz Göçek, “NATO in the Black Sea,” NATO Association, June 11, 2019, accessed date December 20, 2022. https://natoassociation.ca/nato-in-the-black-sea/

[xxix] Duygu Çağla Bayram and Özgür Tüfekçi, “Turkey’s Black Sea Vision and Its Dynamics,” Karadeniz Araştırmaları Dergisi 15, no. 57 (2018): 5-6.

[xxx] Panagiota Manoli, Reinvigorating Black Sea Cooperation: A Policy Discussion – Policy Report III (Bucharest: The Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation, November 2010), 8.

[xxxi] Mustafa Aydın, Europe’s Next Shore: The Black Sea Region after EU Enlargement (Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies, June 2004), 5.

[xxxii] “Erdoğan: Rusya’nın Sözde Donetsk ve Luhansk’ı Tanıma Kararı Kabul Edilemez,” Euronews, February 22, 2022, accessed date February 2, 2022. https://tr.euronews.com/2022/02/22/erdogan-rusya-n-n-sozde-donetsk-ve-lugansk-tan-ma-karar-kabul-edilemez

[xxxiii] “Bölgeler,” Ministry Foreign Affairs of Turkey, accessed date November 12, 2022. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/sub.tr.mfa?03af1e06-bd93-40cb-ae4f-2c4ac27672e7

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 468-469.

[xxxvi] Hasret Çomak et al., “Karadeniz’de Yeni Gelişmeler, Ukrayna Krizi ve Türkiye,” in Uluslararası Politikada Ukrayna Krizi, eds. Hasret Çomak et al. (Istanbul: Beta Yayınevi, 2014), 139.

[xxxvii] Serhat Kuzucu, Kırım Hanlığı ve Osmanlı Rus Savaşları (Istanbul: Selenge Yayınları, 2017), 34.

[xxxviii] Çomak et al., “Karadeniz’de Yeni Gelişmeler,”139.

[xxxix] Akif Kireççi and Selim Tezcan, Kırım’ın Kısa Tarihi (Ankara: Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015), 34-36.

[xl] Rıfat Uçarol, Siyasi Tarih (Istanbul: Der Yayınları, 2014), 59.

[xli] William Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy since 1774 (London: Routledge, 2012), 1-35.

[xlii] “Karadeniz’in Rekabet Alanına Dönüşmemesi İçin Gayret Gösteriyoruz,” Savunmasanayi.org, March 1, 2022, accessed date March 29, 2022. https://www.savunmasanayi.org/karadenizin-rekabet-alanina-donusmemesi-icin-gayret-gosteriyoruz/

[xliii] Hettne, “The New Regionalism,” 7.

[xliv] Costa Buranelli, “The English School,” 27.

[xlv] Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, “2020 Yılına Girerken Girişimci ve İnsani Dış Politikamız, Dışişleri Bakanlığı’nın 2020 Mali Yılı Bütçe Tasarısının TBMM Plan ve Bütçe Komisyonu’na Sunulması Vesilesiyle Hazırlanan Kitapçık,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 18, 2019, accessed date August 13, 2022, 139-140. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/site_media/html/2020-yilina-girerken-girisimci-ve-insani-dis-politikamiz.pdf

[xlvi] Sergiu Celac and Panagiota Manoli, “Towards a New Model of Comprehensive Regionalism in the Black Sea Area,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 6, no. 2 (2006): 195.

[xlvii] Mehmet Şah Yılmaz et al., “Dışişleri Bakanı Çavuşoğlu: Karadeniz’de Güvenlik Koridoru Açılmasını Görüşmek Üzere Lavrov 8 Haziran’da Gelecek,” Anadolu Agency, May 31, 2022, accessed date October 28, 2022. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/gundem/disisleri-bakani-cavusoglu-karadenizde-guvenlik-koridoru-acilmasini-gorusmek-uzere-lavrov-8-haziranda-gelecek/2601669

[xlviii] Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, “Twitter Post,” September 3, 2021, accessed date August 26, 2022. https://twitter.com/mevlutcavusoglu/status/1433790018011779090; “Karadeniz Ekonomik İşbirliği 25. Yılında Türkiye’nin Ev Sahipliğinde Toplandı,” Dış Ekonomik İlişkiler Kurulu, May 11, 2017, accessed date October 22, 2022. https://www.deik.org.tr/basin-aciklamalari-karadeniz-ekonomik-isbirligi-25-inci-yilinda-turkiye-nin-ev-sahipliginde-toplandi

[xlix] “Karadeniz Deniz İşbirliği Görev Grubu Teşkiline Dair Anlaşma,” Turkish Ministry of National Defense, 2001, accessed date November 12, 2022. https://www.dzkk.tsk.tr/icerik.php?icerik_id=248&dil=tr&blackseafor=1

[l] Faruk Sönmezoğlu, Son Yıllarda Türk Dış Politikası 1991-2015 (Istanbul: Der Yayınları 2016), 736.

[li] “Karadeniz Uyumu Harekâtı,” Ministry Foreign Affairs of Turkey, October 6, 2006, accessed date September 17, 2021. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_150---6-ekim-2006_-karadeniz-uyumu-harekati-hk_.tr.mfa

[lii] “Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre,” United Nations, 2022, accessed date January 18, 2023. https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative

[liii] “Tahıl Koridoru Anlaşması Nedir, Hangi Ülkeler İmzaladı? Tahıl Koridoru Anlaşması Kapsamı!,” CNN Türk, July 23, 2022, accessed date January 20, 2023. https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/tahil-koridoru-anlasmasi-nedir-hangi-ulkeler-imzaladi-tahil-koridoru-anlasmasi-kapsami

[liv] “Bakan Çavuşoğlu’ndan Tahıl Koridoru Açıklaması: Mayınlar Temizlenmeden Güvenli Hat Açılabilir,” TRT Haber, June 15, 2022, accessed date January 22, 2023. https://www.trthaber.com/haber/gundem/bakan-cavusoglundan-tahil-koridoru-aciklamasi-mayinlar-temizlenmeden-guvenli-hat-acilabilir-688057.html; Ihvan Radoykov, “Bulgaristan, Türkiye ve Romanya, Karadeniz’de Mayın Arama Operasyonu Düzenleyecek,” Anadolu Agency, October 20, 2023, accessed date January 15, 2024. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/dunya/bulgaristan-turkiye-ve-romanya-karadeniz-de-mayin-arama-operasyonu-duzenleyecek/3027649

[lv] Hettne, “The New Regionalism,” 8.

[lvi] Shahar Hameiri, “Theorising Regions through Changes in Statehood: Rethinking the Theory and Method of Comparative Regionalism,” Review of International Studies 39, no. 2 (2013): 313-335.

[lvii] Costa Buranelli, “The English School,” 26.

[lviii] Hettne, “The New Regionalism,” 7.

[lix] Ibid.

[lx] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 467-472.

[lxi] Ibid., 463.

[lxii] Ibid., 461-464.

[lxiii] Ibid., 467-468.

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Ibid., 462-466.

[lxvi] The 1,000 Houses project was proposed by Crimean Tatars in 1994, on the 50th anniversary of the 1944 deportations, and then-President Suleyman Demirel agreed to implement the project. The project provides housing for at least some of the homeless Tatar Turks in Crimea.

[lxvii] “Türkiye Development Aid 2017 Report,” Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, 2017, accessed date October 3, 2022. https://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/2019/Turkish%20Development%20Assistance%20Report%202017/Kalkinma2017EngWeb.pdf; “Türkiye Development Aid 2018 Report,” Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, 2018, accessed date October 5, 2022. https://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/2019/Faaliyet%20Raporu%202018/TikaFaaliyetWeb.pdf; “Türkiye Development Aid 2019 Report,” Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, 2019, accessed date October 7, 2022. https://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/sayfa/publication/2019/TurkiyeKalkinma2019Web.pdf

[lxviii] “2019 Annual Report,” Yunus Emre Institute, 2019, accessed date October 9, 2022. https://www.yee.org.tr/sites/default/files/yayin/yee_2019_v2_31122020.pdf

[lxix] “2015 Annual Report,” Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities, 2015, accessed date October 11, 2022. https://ytbweb1.blob.core.windows.net/files/resimler/activity_reports/2015-faaliyet-raporu.pdf

[lxx] See, Gökberk Kuzgunkaya, “Kiev’de Türkçe Kurslara Kayıtlar Devam Ediyor,” Ukr-Ayna, January 21, 2018, accessed date October 17, 2022. https://www.ukr-ayna.com/kievde-turkce-kurslara-kayitlar-devam-ediyor/

[lxxi] “Presentation Catalog,” Turkish Maarif Foundation, accessed date October 13, 2022, 12-17. https://turkiyemaarif.org/uploads/TanitimKataloguTR.pdf

[lxxii] “TİKA ve Kırımoğlu, Kiev’de Kırım Tatar Kültür Merkezi Açtı,” Kırım Foundation, October 28, 2016, accessed date December 28, 2023. https://www.kirimdernegi.org.tr/haberler/342-tika-ve-kirimoglu-kiev-de-kirim-tatar-kultur-merkezi-acti

[lxxiii] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 466-469.

[lxxiv] Buzan and Waever, Regions and Powers, 44.

[lxxv] Buzan, “Regional Security,” 140-144.

[lxxvi] Barry Buzan, Ole Waever, and Jaap De Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publications, 1989), 201.

[lxxvii] Hettne and Söderbaum, “Rise of Regionness,” 466-469.

[lxxviii] Buzan, “How Regions were Made,” 39.

[lxxix] Kudret Özersay, “Montreux Boğazlar Sözleşmesi,” in Türk Dış Politikası: Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar, ed. Baskın Oran, vol.1 (Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2018), 370-384.

[lxxx] “Akar’dan ‘Montrö’ Vurgusu: Aşındırılması, Statükonun Bozulması Kimseye Yarar Sağlamaz,” TRT Haber, March 1, 2022, accessed date November 25, 2022. https://www.trthaber.com/haber/gundem/akardan-montro-vurgusu-asindirilmasi-statukonun-bozulmasi-kimseye-yarar-saglamaz-659493.html

[lxxxi] “Putin’in Formülü ne Anlama Geliyor? Türkiye’ye Yeni Kapı!,” Milliyet, October 23, 2022, accessed date December 29, 2022. https://www.milliyet.com.tr/ekonomi/putinin-formulu-ne-anlama-geliyor-turkiyeye-yeni-kapi-6840243

[lxxxii] “Dışişleri Bakanı Çavuşoğlu: Türkiye Hali Hazırda Bir Enerji Merkezi Olma Kapasitesine Sahip,” NTV Haber, October 14, 2022, accessed date November 23, 2022. https://www.ntv.com.tr/dunya/disisleri-bakani-cavusoglu-turkiye-hali-hazirda-bir-enerji-merkezi-olma-kapasitesine-sahip,swk2OcYHvE26wESlnjk5OQ

[lxxxiii] “2015-2019 Strategic Plan,” Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, 2015, accessed date November 23, 2022, 25. http://www.sp.gov.tr/upload/xSPStratejikPlan/files/nQbTc+etkb_stratejik_plani.pdf

[lxxxiv] “Çavuşoğlu: Karadeniz’in Gerginlikler Denizi Olmasını İstemiyoruz,” NTV Haber, February 2, 2019, accessed date November 21, 2022. https://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/cavusoglu-karadenizin-gerginlikler-denizi-olmasini-istemiyoruz,kQsCCF%20tnkGVFKjCgGTy4w

Bibliography

“2015 Annual Report,” Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities. 2015. Accessed date October 11, 2022. https://ytbweb1.blob.core.windows.net/files/resimler/activity_reports/2015-faaliyet-raporu.pdf

“2015-2019 Strategic Plan.” Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. 2015. Accessed date November 23, 2022. http://www.sp.gov.tr/upload/xSPStratejikPlan/files/nQbTc+etkb_stratejik_plani.pdf

“2019 Annual Report.” Yunus Emre Institute. 2019. Accessed date October 9, 2022. https://www.yee.org.tr/sites/default/files/yayin/yee_2019_v2_31122020.pdf

Acharya, Amitav. “Comparative Regionalism: A Field Whose Time has Come?” The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 47, no.1 (2012): 3-15.

____. “How Ideas Spread. Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organization 58, no. 2 (2004): 239-275.

“Akar’dan ‘Montrö’ Vurgusu: Aşındırılması, Statükonun Bozulması Kimseye Yarar Sağlamaz.” TRT Haber. March 1, 2022. Accessed date November 25, 2022. https://www.trthaber.com/haber/gundem/akardan-montro-vurgusu-asindirilmasi-statukonun-bozulmasi-kimseye-yarar-saglamaz-659493.html

Antonenko, Oksana. “Towards a Comprehensive Regional Security Framework in the Black Sea Region After the Russia-Georgia War.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9, no. 3 (2009) 259-269.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Geographical Blessing Versus Geopolitical Curse: Great Power Security Agendas for the Black Sea Region and a Turkish Alternative.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9, no. 3 (2009): 271-285.

____. “Regional Cooperation in the Black Sea and the Role of Institutions.” PERCEPTIONS: Journal of International Affairs 10, no. 3 (2005): 57-83.

____. Europe’s Next Shore: The Black Sea Region after EU Enlargement. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies, June 2004.

“Bakan Çavuşoğlu’ndan Tahıl Koridoru Açıklaması: Mayınlar Temizlenmeden Güvenli Hat Açılabilir.” TRT Haber. June 15, 2022 Accessed date January 22, 2023. https://www.trthaber.com/haber/gundem/bakan-cavusoglundan-tahil-koridoru-aciklamasi-mayinlar-temizlenmeden-guvenli-hat-acilabilir-688057.html

Bayram, Duygu Çağla, and Özgür Tüfekçi. “Turkey’s Black Sea Vision and Its Dynamics.” Karadeniz Araştırmaları Dergisi 15, no. 57 (2018): 1-16.

Bazoğlu Sezer, Duygu. “Turkey in the New Security Environment in the Balkan and Black Sea Region.” in Turkey Between East and West, edited by Vojtech Mastny, 70-96. New York: Routledge, 1996.

“Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre.” United Nations. 2022. Accessed date January 18, 2023. https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative

“Bölgeler.” Ministry Foreign Affairs of Turkey. Accessed date November 12, 2022. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/sub.tr.mfa?03af1e06-bd93-40cb-ae4f-2c4ac27672e7

Buzan, Barry, and Ana Gonzalez Pelaez. International Society and the Middle East: English School Theory at the Regional Level. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Buzan, Barry, and Ole Waever. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Waever, and Jaap De Wilde. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publications, 1989.

Buzan, Barry. “How Regions were Made, and the Legacies for World Politics: An English School Reconnaissance.” In International Relations Theory and Regional Transformation, edited by T.V. Paul 22-46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

____. “Regional Security Complex Theory in the Post-Cold War World.” In Theories of New Regionalism, edited by Fredrik Söderbaum and Timothy M. Shaw, 140-159. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Çavuşoğlu, Mevlüt. “2020 Yılına Girerken Girişimci ve İnsani Dış Politikamız, Dışişleri Bakanlığı’nın 2020 Mali Yılı Bütçe Tasarısının TBMM Plan ve Bütçe Komisyonu’na Sunulması Vesilesiyle Hazırlanan Kitapçık.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs. November 18, 2019. Accessed date August 13, 2022. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/site_media/html/2020-yilina-girerken-girisimci-ve-insani-dis-politikamiz.pdf

____. “Twitter Post.” September 3, 2021. Accessed date August 26, 2022. https://twitter.com/mevlutcavusoglu/status/1433790018011779090

“Çavuşoğlu: Karadeniz’in Gerginlikler Denizi Olmasını İstemiyoruz.” NTV Haber. February 2, 2019. Accessed date November 21, 2022. https://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/cavusoglu-karadenizin-gerginlikler-denizi-olmasini-istemiyoruz,kQsCCF%20tnkGVFKjCgGTy4w

Celac, Sergiu, and Panagiota Manoli. “Towards a New Model of Comprehensive Regionalism in the Black Sea Area.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 6, no. 2 (2006): 193-205.

Ciută, Felix. “Region? Why Region? Security, Hermeneutics, and the Making of the Black Sea Region.” Geopolitics 13, no. 1 (2008): 120-147.

Çomak, Hasret, et al. “Karadeniz’de Yeni Gelişmeler, Ukrayna Krizi ve Türkiye.” In Uluslararası Politikada Ukrayna Krizi, edited by Hasret Çomak et al., 137-167. Istanbul: Beta Yayınevi, 2014.

____. Karadeniz Jeopolitiği. Istanbul: Beta Yayınevi, 2018.

Costa Buranelli, Filippo, and Aliya Tskhay. “Regionalism.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, edited by Renee Marlin Bennett, 1-21. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Costa Buranelli, Filippo. “Do you Know What I Mean? ‘Not Exactly’: English School, Global International Society, and the Polysemy of Institutions.” Global Discourse 5, no. 3 (2015): 499-514.

____. “The English School and Regional International Societies: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections.” In Regions in International Society, edited by Ales Karmazin et al., 22-44. Brno: MUNI Press, 2014.

“Dışişleri Bakanı Çavuşoğlu: Türkiye Hali Hazırda Bir Enerji Merkezi Olma Kapasitesine Sahip.” NTV Haber. October 14, 2022. Accessed date November 23, 2022. https://www.ntv.com.tr/dunya/disisleri-bakani-cavusoglu-turkiye-hali-hazirda-bir-enerji-merkezi-olma-kapasitesine-sahip,swk2OcYHvE26wESlnjk5OQ

Dunne, Tim. “New Thinking on International Society.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 3, no. 2 (2001): 223-244.

“Erdoğan: Rusya’nın Sözde Donetsk ve Luhansk’ı Tanıma Kararı Kabul Edilemez.” Euronews. February 22, 2022. Accessed date February 2, 2022. https://tr.euronews.com/2022/02/22/erdogan-rusya-n-n-sozde-donetsk-ve-lugansk-tan-ma-karar-kabul-edilemez

Göçek, Naz. “NATO in the Black Sea.” NATO Association. June 11, 2019. Accessed date December 20, 2022. https://natoassociation.ca/nato-in-the-black-sea/

Hajizada, Mukhtar. “Challenges and Opportunities for Establishing a Security Community in the Wider Black Sea Area.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 18, no. 4 (2018): 529-548.

Hale, William. Turkish Foreign Policy since 1774. London: Routledge, 2012.

Hameiri, Shahar. “Theorising Regions through Changes in Statehood: Rethinking the Theory and Method of Comparative Regionalism.” Review of International Studies 39, no. 2 (2013): 313-335.

Hettne, Björn, and Fredrik Söderbaum. “Theorising the Rise of Regionness.” New Political Economy 5, no. 3 (2000): 457-472.

Hettne, Björn. “The New Regionalism: Implications for Development and Peace.” In The New Regionalism: Implications for Global Development and International Security, edited by Björn Hettne, Andras Inotai, and Osvaldo Sunkel, 1-50. Forssan Kirjapaino Oy: UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research, 1994.

Hurrell, Andrew. “Regionalism in Theoretical Perspective.” In Regionalism in World Politics: Regional Organization and International Ordered, edited by Louise Fawcett and Andrew Hurrell, 37-73. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Jay, Peter. “Regionalism as Geopolitics.” Foreign Affairs 58, no. 3 (1979): 485-514.

“Karadeniz Deniz İşbirliği Görev Grubu Teşkiline Dair Anlaşma.” Turkish Ministry of National Defense. 2001. Accessed date November 12, 2022. https://www.dzkk.tsk.tr/icerik.php?icerik_id=248&dil=tr&blackseafor=1

“Karadeniz Ekonomik İşbirliği 25. Yılında Türkiye’nin Ev Sahipliğinde Toplandı.” Dış Ekonomik İlişkiler Kurulu. May 11, 2017. Accessed date October 22, 2022. https://www.deik.org.tr/basin-aciklamalari-karadeniz-ekonomik-isbirligi-25-inci-yilinda-turkiye-nin-ev-sahipliginde-toplandi

“Karadeniz Uyumu Harekâtı.” Ministry Foreign Affairs of Turkey. October 6, 2006. Accessed date September 17, 2021. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_150---6-ekim-2006_-karadeniz-uyumu-harekati-hk_.tr.mfa

“Karadeniz’in Rekabet Alanına Dönüşmemesi İçin Gayret Gösteriyoruz.” Savunmasanayi.org. March 1, 2022. Accessed date March 29, 2022. https://www.savunmasanayi.org/karadenizin-rekabet-alanina-donusmemesi-icin-gayret-gosteriyoruz/

Kireççi, Akif, and Selim Tezcan. Kırım’ın Kısa Tarihi. Ankara: Ahmet Yesevi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2015.

Kuzgunkaya, Gökberk. “Kiev’de Türkçe Kurslara Kayıtlar Devam Ediyor.” Ukr-Ayna. January 21, 2018. Accessed date October 17, 2022. https://www.ukr-ayna.com/kievde-turkce-kurslara-kayitlar-devam-ediyor/

Kuzucu, Serhat. Kırım Hanlığı ve Osmanlı Rus Savaşları. Istanbul: Selenge Yayınları, 2017.

Lake, David, and Patrick Morgan. Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

Manoli, Panagiota. “Where is Black Sea Regionalism Heading?” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 323-339.

____. Reinvigorating Black Sea Cooperation: A Policy Discussion – Policy Report III. Bucharest: The Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation, November 2010.

____. The Dynamics of Black Sea Subregionalism. London: Routledge, 2012.

Özdamar, Özgür. “Security and Military Balance in the Black Sea Region.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 341-359.

Özersay, Kudret. “Montreux Boğazlar Sözleşmesi.” In Türk Dış Politikası: Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar, edited by Baskın Oran, vol.1, 370-384. Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2018.

Pavliuk, Oleksandr, and Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze. The Black Sea Region: Cooperation and Security Building. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Petriashvili, Sophia. “Where is the Black Sea Region in Turkey’s Foreign Policy?” Turkish Policy Quarterly 14, no. 3 (2006): 105-112.

“Presentation Catalog.” Turkish Maarif Foundation. Accessed date October 13, 2022. https://turkiyemaarif.org/uploads/TanitimKataloguTR.pdf

“Putin’in Formülü ne Anlama Geliyor? Türkiye’ye Yeni Kapı!” Milliyet. October 23, 2022. Accessed date December 29, 2022. https://www.milliyet.com.tr/ekonomi/putinin-formulu-ne-anlama-geliyor-turkiyeye-yeni-kapi-6840243

Radoykov, Ihvan. “Bulgaristan, Türkiye ve Romanya, Karadeniz’de Mayın Arama Operasyonu Düzenleyecek.” Anadolu Agency. October 20, 2023. Accessed date January 15, 2024. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/dunya/bulgaristan-turkiye-ve-romanya-karadeniz-de-mayin-arama-operasyonu-duzenleyecek/3027649

Rusu, Diana. “Regionalization in the Black Sea Area: A Comparative Study.” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 11, no. 2 (2011): 47-65.

Sander, Oral. Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası. Istanbul: İmge Yayınları, 1998.

Sönmezoğlu, Faruk. Son Yıllarda Türk Dış Politikası 1991-2015. Istanbul: Der Yayınları 2016.

“Tahıl Koridoru Anlaşması Nedir, Hangi Ülkeler İmzaladı? Tahıl Koridoru Anlaşması Kapsamı!” CNN Türk. July 23, 2022. Accessed date January 20, 2023. https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/tahil-koridoru-anlasmasi-nedir-hangi-ulkeler-imzaladi-tahil-koridoru-anlasmasi-kapsami