Efe Tokdemir, Bilkent University

Melike Metintaş, Bilkent University

Seçkin Köstem, Bilkent University

Abstract

Türkiye - United States relations have a multifaceted character and have spanned a long period, witnessing ups and downs throughout their historical trajectory. Türkiye’s relations with and foreign policy towards the US have been closely monitored by the public, and diverse perspectives towards the US have emerged within Turkish public opinion over time. This paper investigates the various factors that affect Turkish public opinion towards the US. Previous studies have generally examined public opinion through the demand side, exploring what features of the public predict their behavior towards other countries. In this research, we examine what exactly it is about the US that the public likes or dislikes. The research question of this article is: What are the determinants of the variation in individuals’ foreign policy attitudes towards the US in Türkiye? By answering this question through survey data conducted in 2021, we aim to present the economic, security-related, and political reasons behind the Turkish public’s positive and negative attitudes toward the US. The findings demonstrate that individuals are influenced by various dimensions pertaining to the US and its relations with Türkiye. The respondents’ demographic characteristics and political and foreign policy attitudes have resulted in disparate opinions regarding these multiple dimensions.

1.Introduction

The public opinion literature has extensively examined the views of individuals in various parts of the world towards the United States (US) and other major powers. In this paper, we attempt to answer the following research question: What are the determinants of the variation in individuals’ foreign policy attitudes towards the US in Türkiye? We believe this question continues to be an important and unexplored dimension of Türkiye’s relationship with and foreign policy towards the US. Türkiye has had close security ties with the US since the beginning of the Cold War. The relationship has had multiple crises during and after the Cold War period, significantly shaping Turkish public opinion. Despite its commitment to the transatlantic alliance, the Turkish government has pursued strategic autonomy from the Western-led international order in the past decade.[i] At the same time, Turkish public opinion has had persistent anti-American attitudes, as demonstrated by various public opinion surveys.[ii]

This article argues that multiple characteristics of the US and various dimensions of US-Türkiye bilateral relations shape Turkish public opinion towards the US. Therefore, we aim to highlight the complexity behind the formation of individual attitudes towards the US in Turkish society. Instead of making a theoretical argument, the article offers a descriptive study that aims to explore the multiple dimensions of attitudes towards the US in Türkiye in detail. As the article will demonstrate, different dimensions of US-Türkiye relations and US foreign policy practices lead to the formation of public opinion in Türkiye. At the same time, we show that the varying demographic, societal, and ideological characteristics and inclinations of individuals have an influence on the formation of public opinion towards the US.

The article aims to make multiple contributions to the literature. First, we present a theoretically driven account of the sources of foreign policy attitudes towards the US. So far, the literature has mostly explored whether the public has positive or negative attitudes towards the US and other major powers.[iii] Instead, we investigate the economic, security-related, and political reasons behind positive attitudes towards the US. Second, the literature that examines the sources of individual attitudes mostly looks at the demand side – what features of the society and individuals predict their attitudes and behaviors towards other countries.[iv] Instead, our study explores the supply side by studying what exactly it is about the US that the public likes or dislikes. Third, the literature generally tends to explain negative attitudes towards other countries. For example, in the vast literature on attitudes toward the US, the dependent variable is typically anti-Americanism.[v] However, most regional and global powers heavily use soft power-building strategies and public diplomacy promotion efforts to attract positive attention. Bearing in mind the asymmetry of the impacts derived from positive vs. negative attitudes on foreign policy actions, we are interested in explaining the reasons why individuals form positive attitudes towards the US and how security/geopolitics, economy, identity, and domestic factors play out vis-à-vis each other.

The article is structured as follows. The next section presents a literature review on global attitudes towards the US with a specific focus on anti-Americanism, followed by a discussion on the sources of anti-Americanism in Turkish public opinion. The paper then explains the data and research design by presenting the results from an online survey conducted in April 2021 that aims to capture how individuals’ foreign policy dispositions and domestic politics shape attitudes toward the US. The final section concludes the paper with a discussion on its contribution to the literature, limitations and implications for future research.

2.The Sources of Anti-Americanism: A Literature Review

Anti-Americanism is a complex topic encompassing negative public opinion against the US, the US Government, or American society. It can also include a bias towards the policies and developments in world politics associated with the US government. The early roots of anti-Americanism date back to the 19th century when the US emerged as a global actor. Yet the concept took on a new and more complex character at the end of the Cold War with growing criticisms of the American-led globalization and capitalism worldwide.[vi] Anti-Americanism gained a violent character with the 9/11 attacks of the terrorist organization Al Qaeda, which paved the way for “The War on Terror.” Since 9/11, there has been an increase in scholarly research and political debate on the topic.[vii]

The literature highlights several factors that influence negative opinions against the US in a foreign country. There is a consensus in the literature on the complex and polarizing nature of anti-Americanism. As Rubinstein and Smith argue, ‘Anti-Americanism can be likened to an onion; it has many layers, and these need to be peeled and examined separately.’[viii] Scholars have developed different definitions of anti-Americanism over the past decades. The early generation of experts on the issue described anti-Americanism with the actions or statements that targeted the policy, culture, values, or citizens of the US,[ix] while some of the cultural explanations conceptualized the term as prejudice.[x]

On the other hand, a useful and well-known approach arises from the scholars who define anti-Americanism with the dynamic changes of individual attitudes towards the US that depend on time and conditions.[xi] This strand of the literature demonstrates the multifaceted nature of anti-Americanism by rejecting the characterization of this concept as a uniform phenomenon. Katzenstein and Keohane, for example, examine the profile of anti-American attitudes by demonstrating how the interplay of individuals’ opinions, distrust, and bias shapes their attitudes toward the US over time.[xii] Meunier exemplified this multidimensional and dynamic approach to anti-Americanism in France by demonstrating how the French public held a negative opinion of the Americanization of globalization.[xiii] Moreover, Chiozza finds that there is no single overarching demographic or attitudinal factor from which anti-American attitudes stem.[xiv]

The problem with such complex and varying definitions of anti-Americanism is that it is hard to measure what is essential for empirically testing public opinion towards the US. Yet, shifts in the global order, critical junctures such as 9/11 and the Iraq War, combined with the growth in the number of democracies have enhanced the political and scholarly interest in how publics react to these events.[xv] In parallel, many recent international surveys have provided data about how public opinion is shaped by the US and its policies in different parts of the world. The Gallup International Survey, the Pew Research for Global Attitudes, the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA), and the United States Information Agency (USIA) have made concerted efforts to measure attitudes towards the US worldwide. The public opinion literature in the context of anti-Americanism has taken advantage of these easily accessible data sets from large global opinion surveys.

Several studies have focused on empirical sources and consequences of anti-Americanism worldwide by conducting research relying on both quantitative and qualitative methods. Based on the scholarly literature, the sources of anti-Americanism can be examined in two categories: US and non-US factors. The scholars within these categories explain anti-American sentiments in the context of what the US does, what the US is, and a synthesis of these two attributes.[xvi] The first branch of the literature on sources of anti-Americanism has focused on individuals’ dissatisfaction with the US for what it does, namely, its unilateralist behavior in global affairs, hypocritical foreign policies, and political, militaristic, and social oppression towards other countries. Mastanduno explains the countries’ dissatisfaction with American unilateralism through the US’s disrespect for several multilateral institutions like the United Nations by arguing that such behavior causes increasing ire within the international community.[xvii] Also, Huntington argues that while the US labeled several countries as ‘rogue’ states, in the eyes of many others it is itself becoming a ‘rogue superpower’.[xviii] On the other hand, Johnston & Stockmann and Tokdemir examine anti-Americanism in the contexts of China and Lebanon, respectively, and find that the most consistently negative views towards the US concern its overall strategy of being a hegemon in the international order, and being perceived as the ally of out-groups.[xix]

Moreover, the US’s alleged hypocrisy impedes the individual’s trust in the US and its policies. For example, Moghaddam presents a dataset hypothesizing that individuals’ perceived injustice from the US is associated with the violent behavior that constitutes the first step of terrorism.[xx] The US support for authoritarian regimes and these regimes’ crackdowns on any form of opposition reinforces anti-Americanism among these countries’ publics.[xxi] Some scholars who are particularly focusing on anti-Americanism in the Arab world argue that the US’s pro-Israeli position, which comes in the form of economic, political, and military assistance to Israel, and its biased position towards the Arab-Israeli conflict, antagonizes the Arab countries’ public opinion.[xxii]

As a phenomenon of public opinion, anti-Americanism does not emerge only as a response to what the US does, it is also shaped by how local political leaders of foreign countries describe the US for their own political interests.[xxiii] Also, as Furia and Lucas show, the source of anti-Americanism may be based on politics as opposed to cultural or social variables.[xxiv] Empirically, several scholars have shown how policy-makers manipulated the US image for their political gain and interests. For example, Mesitte demonstrates that the political leaders in post-1945 France, Greece, and Italy used anti-American rhetoric to win elections.[xxv] Blaydes and Linzer also argue that both secularist and Islamist political parties in Arab countries seek to lay claim to anti-Americanism because it remains an issue for both sides to possess credible associations.[xxvi] Moreover, by conducting an individual-level regression analysis in several Latin American countries, Azpuru and Boniface find that the level of anti-Americanism increases at the individual level when the domestic leader has a negative stance towards the US.[xxvii]

The literature has also discussed the consequences of anti-Americanism for US foreign policy priorities and interests. Accordingly, the erosion of the US image and US-led values in global terms might impede American strategic interest in the long run. In short, the consolidation of anti-Americanism worldwide hurts US hard and soft power.[xxviii] The consequences of anti-Americanism could have an adverse impact in multiple realms, such as military operations, diplomacy, trade, and foreign aid.

To remedy the negative consequences for US foreign policy, Washington has developed strategies to boost its reputation in the eyes of foreign publics. In the aftermath of 9/11, the US adopted a more proactive approach for public diplomacy, integrating it as a central component of its global strategy. The objective of this strategy was to win hearts and minds of the publics in multiple countries. However, an analysis of the relevant literature reveals that the US efforts in this regard have not yielded the desired outcomes. For example, intervening in elections to support democratization in developing countries[xxix] and support for women’s representation in politics in countries going through a process of democratization, did not result in an increase in favorable opinion towards the US.[xxx] Contrary to the expectations, US-based student exchange programs, which are associated with the diffusion of liberal ideas and democratic practices within authoritarian states[xxxi], have only had a limited effect in cultivating favorable perceptions of the US beyond the elites and among the public.

Moreover, another traditional tool to foster pro-American sentiments and attitudes is foreign aid. As Fleck & Kilby argue, a remarkable increase in American aid after 9/11 and the War on Terror demonstrates that the US benefits from foreign aid as an instrument to renew its image.[xxxii] Through a survey of citizens in 14 countries that receive US military aid, Allen et al. find that the overall positivity rate increases after military-aid contact with the US.[xxxiii] However, similar to other public diplomacy efforts of the US, such a strategy has not always given the desired outcomes and has even sometimes resulted in the feeding of anti-American opinion among individuals. For example, Tokdemir notes that American foreign aid can feed anti-American attitudes because it indirectly creates “winners and losers” in a society; losers within these countries may never benefit from such aid and thus may harbor strong anti-American opinions.[xxxiv]

2.1. Sources of Anti-Americanism in Turkish Public Opinion

While global trends influence Turkish public opinion towards the US, it also has unique characteristics in some cases. The country’s geostrategic location between Europe and Asia; long-standing historical ties with the US; NATO membership; and internal dynamics are all influential for the public’s view. Moreover, anti-American attitudes in Türkiye are embraced by nearly all segments of Turkish society; secular, nationalist, leftist, and Islamist traditions can share anti-American attitudes with different motivations.[xxxv]

The scholarly literature has investigated anti-American sentiments among the Turkish public through what the US is and does as well as based on internal factors. Still, there are important gaps to fill in terms of the sources of attitudes towards the US in Türkiye. First, the literature mostly focuses on the demand side, as characteristics of the society are the main determinants of attitudes and behavior. Second, the literature focuses on negative attitudes toward the US, typically anti-Americanism, and does not delve deeply into individuals’ positive opinions about the US or the factors that might potentially influence individuals’ attitudes positively. The framework this paper presents regarding the dimensions of Turkish public opinion towards the US begins with evaluating the divergent root causes. The three primary dimensions of the Turkish public opinion towards the US can be categorized as political, economic, and security related. These three dimensions in fact take their roots from long-standing historical ties and have been shaped by different issues and events over time.

Firstly, the roots of the Turkish public’s current view on the US date back to the early Cold War period. The US–Türkiye relationship entered a new phase with the Cold War, and since then, the Turkish public’s perception of the US, its foreign policy, and the transatlantic alliance has been affected by the complex dynamics of the relationship over the decades.[xxxvi] The Truman Doctrine highlighted a common strategic interest between Türkiye and the US. Also, Türkiye became one of the beneficiaries of the Marshall Plan, which directed a large amount of economic foreign aid to the country.[xxxvii] Türkiye’s participation in the Korean War in 1950 and the country’s membership of NATO in 1952 marked critical junctures for Türkiye’s relations with the US.[xxxviii]

Despite the intensifying partnership and converging interests between the US and Türkiye during the Cold War, relations suffered from major drawbacks, which shaped the Turkish public’s opinion towards the US. The Jupiter missile crisis (1962-63), Johnson’s letter (1964), and the Opium Ban (1971) constituted major turning points for the relationship as well as the formation of negative attitudes towards the US.[xxxix] Following each of these events, there was a sharp increase in anti-American sentiments and anti-American protests in Türkiye.[xl] It should be noted that most of the protests during this overall period came from left-wing groups. Criss argues that anti-American sentiments were widespread in the worldviews of the Turkish leftist groups, who regularly organized demonstrations against the US in the 1970s.[xli]

Nevertheless, the roots of anti-Americanism during the Cold War years cannot be explained solely by left-wing motivations. The Cyprus dispute and the following arms embargo imposed by the US in response to the Turkish military operation on the island in 1974 also enflamed a nationalist-sovereign type of anti-Americanism in Türkiye. Criss contends that the roots of anti-Americanism stemmed from the Turkish endeavors to preserve national sovereignty.[xlii] In another leading article, Türkmen conceptualizes Turkish-based anti-Americanism within the definition and typology of Katzenstein and Keohane’s work. Türkmen takes the idiosyncrasies of anti-Americanism in Türkiye into the category of sovereign nationalist anti-Americanism, where national identity is the most important political value behind the negative attitude.[xliii] In a similar vein, Grigoriadis and Aras argue that contemporary anti-American sentiments are primarily nationalist-sovereign, and the anti-Americanism in Turkish public opinion is coupled with an anti-US media landscape.[xliv] Such divergent motivations among the Turkish public sets the country apart from anti-American behavior elsewhere in the Middle East.

As seen above, anti-Americanism in Turkish public opinion overwhelmingly reflected the ideological polarization during the Cold War, but also included some geopolitical concerns. Yet, in the post-Cold War period, the geopolitical and security-related dimensions of anti-Americanism in Türkiye increased. The American war on terror, and specifically the invasion of Iraq in 2003 constituted a turning point for Turkish public perceptions of the US and its foreign policy decisions.

In the build-up to the invasion of Iraq, the US desired to gain support from the Turkish government. Such support involved allocating a large number of US troops to be based on Turkish soil. Yet, the decision by the Turkish Grand National Assembly in March 2003 against cooperating with the US or allowing US troops on Turkish soil was a clear sign of a negative change in the Turkish-American relationship. Meanwhile, the Turkish public also showed a strong objection to the upcoming US invasion of Iraq. According to the Pew Research Center Report in 2002, 83% of respondents were opposed to allowing US forces in Türkiye for the invasion of Iraq.[xlv] Turkish public perception of the US took on both a security-related and a political dimension for two reasons. Firstly, the Turkish public was worried that the American deployment of large military bases in Türkiye was against Turkish sovereignty and national security. Secondly, US actions during the Iraq War were considered by the Turkish public as clear signs of support for Kurdish self-determination both in Northern Iraq and even potentially in southeast Türkiye.

The war in Iraq indeed resulted in an increase in the activities of the PKK (Partiya Karkaren Kurdistan or Kurdistan Workers’ Party). Türkiye has been struggling with PKK terrorism since the mid-1980s. US policy towards the PKK and the impact of that policy on US-Turkish relations and public opinion have undergone transformations in different periods. Despite its support for Türkiye’s counterterrorism efforts during the 1990s, the US changed its policy during and in the immediate aftermath of the Iraq War. The US military and intelligence services provided little support to Ankara against the PKK – Iraqi insurgency and Al Qaeda in Iraq were their main focus. PKK-related complications during the Iraq War period led to a new crisis in bilateral relations, one which negatively influenced both elite and public opinion in Türkiye towards the US.[xlvi] The Syrian civil war that started in 2011 marked another turning point in US-Türkiye relations. Since 2015, the US has built a close partnership with the PKK-linked YPG (Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units) against ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria).[xlvii] As Türkiye’s main national security concerns have continued to revolve around PKK terrorism, the US decision has resulted in increasing anti-Americanism among the Turkish public.

Another turning point in the context of security-related dimensions of the anti-American view in Türkiye was the failed coup attempt of July 2016. The Turkish government has accused the US government of hosting the coup plotters such as Fetullah Gülen, the leader of the Gülenist movement, who has resided in the US since 1999. As other papers in this issue explore in detail, Türkiye’s purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense systems in 2017 and the Pastor Brunson crisis between Ankara and Washington have further exacerbated bilateral ties.[xlviii] The growing military cooperation between the US and Greece in the past few years might have contributed to the Turkish public’s perception of being surrounded by American military bases. Most recently, we would expect Washington’s open political support for Israel’s military operation over Gaza to further consolidate the negative attitudes towards the US among Turkish public opinion.

The negative views of the Turkish public towards the US and its policies have also been observed statistically. According to results from the Kadir Has University public opinion surveys between 2018 and 2022, respondents consistently rank the US as the biggest threat to Türkiye’s national security. Similarly, most respondents think terrorism-related issues constitute the main problem in bilateral relations. In terms of the future of US-Türkiye ties, the majority of the respondents expect bilateral relations to either remain unchanged or get even worse.[xlix] Both the political and security-related dimensions of Turkish public opinion towards the US show that contrary to emotional, religious, or ideological reactions, anti-Americanism in Türkiye is directly related to the resentment of American policies that are viewed as a threat to the country’s sovereignty and interests.

The third dimension of Turkish public opinion towards the US is economic. Since the Marshall Plan, the US has had close economic ties and cooperation with Türkiye in the scope of foreign aid, trade, and investment. Since the Cold War period, the US has played an important role in Türkiye’s adaptation to the market economy. Even though the public’s views on national security and political dimensions have typically seen a negative trend and fed anti-Americanism in Türkiye, the US global economic power and its economic ties with Türkiye have produced a rather positive perception. For example, Sadık found that the Turkish public has increasingly recognized the importance of bilateral trade with the US.[l] Despite moments of crises such as the Trump administration’s decision to increase tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminum in August 2018 and implement sanctions against Türkiye’s Defense Industry Agency in December 2020 under CAATSA[li], bilateral economic ties have remained strong and resilient. American firms have been among the top investors to the Turkish economy in the 21st century alongside European firms. In 2022, Türkiye’s exports to the US reached $22 billion, while it imported goods and services worth $19.5 billion from the US.[lii] Unlike its trade with countries like Russia and China, Türkiye enjoys a trade surplus in its bilateral trade with the US.

3.Empirical Research Design

3.1.Data

To examine the determinants of the variation in individuals’ opinions towards the US in Türkiye, we conducted an online survey reaching out to 2,522 adults in 72 of the 81 districts in Türkiye, from April 20 to April 27, 2021. We utilized the Dynata Research Company’s participant panels for the purpose of sampling, where the respondents were randomly selected from within those panels. Participants completed the survey in, on average, 9 minutes, with a standard deviation of 2.5, a minimum of 2, and a maximum of 24 minutes.

To acquire a robust sample, we excluded the participants who completed the survey in fewer than four minutes or more than 15 minutes. Additionally, we dropped the respondents who did not pass the three attention check questions. In each attention check question, we asked participants to select a specific choice, so that we could ensure they read the questions first. Our sample exhibits similarities in demographic features with the broader Turkish population in terms of gender (i.e., sample: 54% female, population: 51% female), age (i.e., sample median age: 34, population median age: 33), and ethnic identity (i.e., sample Kurdish citizen ratio: 9%; pro-Kurdish political party vote ratio in 2023 general elections: 8.8%). There is a lack of available census data to measure the ratio of ethnic Kurds in the population.

Nonetheless, our sample contains significantly more educated participants and a greater proportion of opposition supporters compared to the general population (2019 incumbent vote: 52%; sample incumbent vote: 29%). According to this, one can conclude that our sample is not nationally representative. Given the challenges posed by the lack of nationwide and high-quality internet access, it is not surprising to reach this result. However, given the similarities between sample vs. population means in terms of gender, age, and ethnic distributions, we have developed weights regarding political party preferences to align our predictions closer to the actual population parameters. To this purpose, we have used the results of the Turkish General Elections held in 2018 to generate the weights and conducted all our primary analyses anew, this time using political party weights.

3.2. Independent variables

Three independent variables form the foundation of our argument: demographic factors, political, and foreign policy attitudes. We constitute these variables based on particular dimensions. Firstly, in demographic variables, we examine people’s age (continuous measure), gender (male vs. female), level of income (6-points scale), and education (9-points scale). Secondly, for political attitudes we include individual frequency of following news (factor analysis predicted scores), interest in voting (4-points Likert scale), anti-government sentiments (vote for opposition or not), religious affiliation (11-points thermometer), and ethnicity (Kurdish vs. others). Lastly, foreign policy attitudes of individuals cover divergent preferences toward foreign policy practices such as left-right nexus, national pride, isolationism, cosmopolitanism, and multilateralist tendencies, all measured in standard batteries reported in the Appendix. These three independent variables are the basis for assessing individuals’ negative and positive attitudes towards the US over time and are determinants to understand the main motivations behind these attitudes.

3.3. Dependent variables

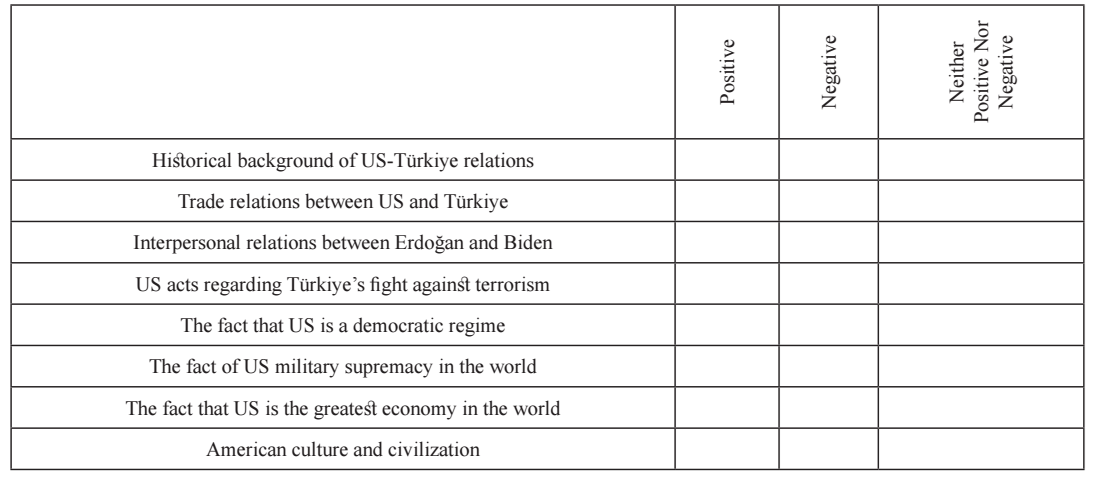

The dependent variables of this research comprise different dimensions that affect individuals’ attitudes towards the US. Survey respondents within Türkiye were questioned about their attitudes towards the US in the context of these divergent dimensions. These dimensions are derived from the main sources of anti-Americanism in Türkiye and the key issues of Türkiye-American relations. Thus, the dependent variables of this research focus on a wide range of aspects of the US, including what it is, what it does, and its long-standing relations with Türkiye. We used a 3-point Likert scale (negative-neutral-positive) to ask respondents which aspects affect their attitudes towards the US and then coded positive as 1, and neutral and negative as 0 in order to determine the factors that contribute to US-Türkiye relations. Each aspect is explained in detail.

Historical Dimension of US-Türkiye Relations: The historical ties between the two countries are the first dimension affecting individual negative and positive attitudes towards the US in Türkiye. We analyze the impact of individuals’ demographic features, foreign policy, and political attitudes on the historical dimension of US-Türkiye relations. The differences in public opinion are embodied within these variables. One can expect that public perception against the US has developed in parallel with the historical political developments in Türkiye; plus, US foreign policy choices have also impacted individuals’ attitudes.

US Economic Power in the World: The influence of US economic power over Turkish public opinion can be characterized in two ways. First is the US role in Türkiye’s marketization and development process. Since the Marshall Plan, Türkiye has received development aid from the US, which has increased economic ties and cooperation between the two countries. Second, is the US’s economic power in the world. Hence, we expect that US economic power and its role in the Turkish economy have also shaped public opinion in Türkiye.

Trade Relations between US-Türkiye: Consistent with the global economic power of the US, we argue that Turkish public opinion recognizes the importance of trade relations between the US and Türkiye.

The Position of the US regarding Türkiye’s Fight against the PKK: US position towards PKK terrorism and Türkiye’s counterterrorism practices have substantial influence over public opinion. In line with the strong objection to US forces in Türkiye during the Iraq War, US support for the YPG forces in Syria has escalated the anti-American attitude in the Turkish public. Thus, we argue that what the US does in the context of the PKK issue is a strong determinant of understanding Turkish public opinion toward the country.

Erdoğan-Biden Relationship: The individual level relations between the leaders of the US and Türkiye, Biden and Erdoğan respectively, might have also influenced Turkish public opinion vis-à-vis the US. Four particular issues came to the agenda for US-Türkiye relations and shaped the Erdoğan-Biden relationship in recent years. These issues are as follows: Türkiye’s purchase of Russian-made S-400 missiles and the following US sanctions; US support for the YPG in Syria; the Eastern Mediterranean dispute over the extraction of natural resources; and Biden’s views on Türkiye’s democratic backsliding during Erdoğan’s rule.[liii] Given these contemporary issues, we argue that leader-to-leader relations have also influenced public opinion toward the US.

American Democracy: Among the main explanations for hostility towards the US has been a rejection of its political system of democracy.[liv] Given that the US has been a democratic success story for more than two centuries and has spread such ideals to the world, it is important to test the effect of regime type on individual attitudes. We argue that both the US democratic political system and its ideal to spread democracy worldwide have influenced the opinions of the different segments of Turkish society.

US Military Supremacy: US military supremacy is expected to shape Turkish public opinion due to both national security concerns and the dynamics of the transatlantic alliance. The fact that the two countries have recently had disagreements over geopolitical issues while maintaining their alliance has generated mixed sentiments among the public. While some individuals support the alliance and view US military supremacy as a guarantee for stability and security, others perceive it as a threat to Türkiye’s security and interests.

American Culture/Civilization: The spread of American values and lifestyle as well as ideas associated with American culture through movies, television shows, news, and other sources have had an impact on individuals from various socio-economic conditions in Türkiye. Here, we argue that the widespread dissemination of such ideas and cultural values may lead to a fragmentation in public attitudes toward the US given the ideological predisposition of Turkish citizens.

Table 1. Questions to Measure Dimensions of pro-American Attitudes

4. Results

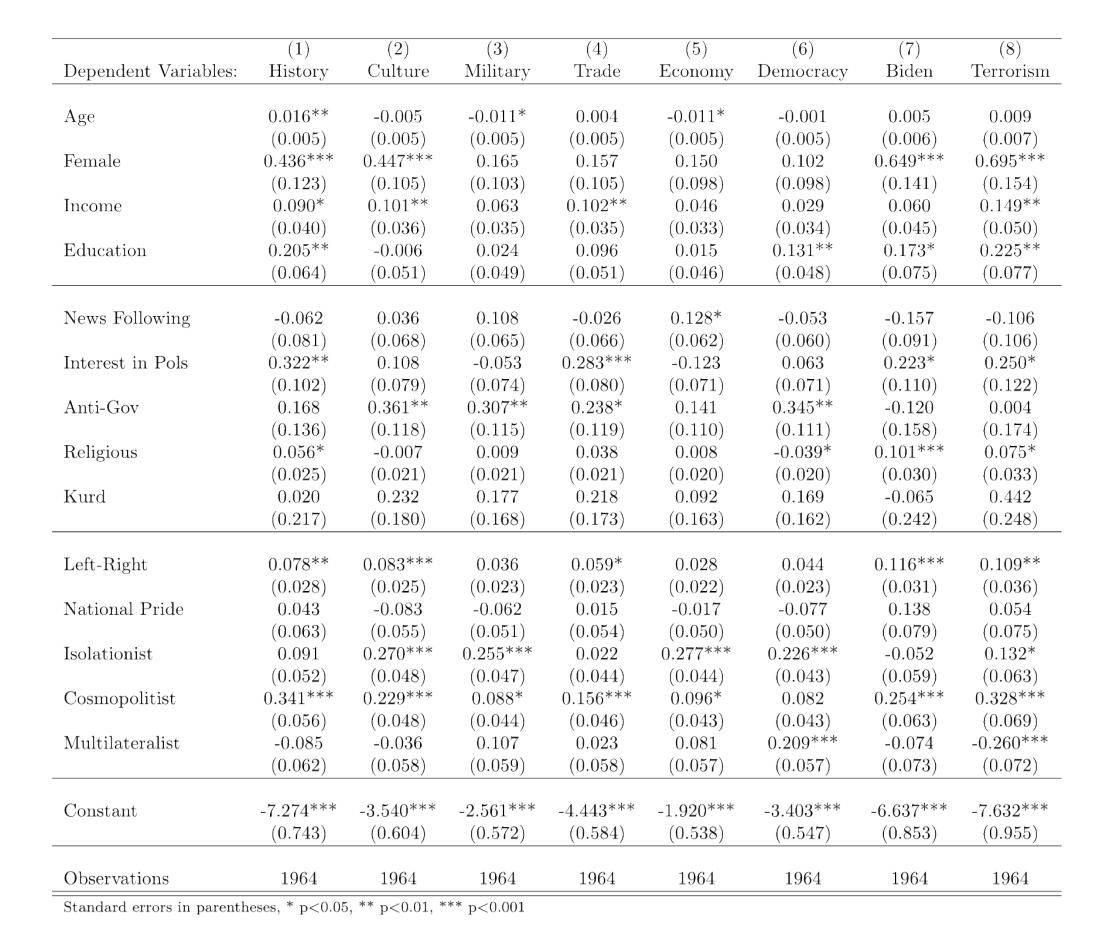

In our research model, we applied a logistic regression given our dependent variable is in binary fashion, to show which dimensions influence the Turkish public opinion towards the US. The findings indicate that Turkish public opinion is influenced by multiple factors related to both countries’ characteristics and foreign policies, as well as bilateral relations between the US and Türkiye. It is also observed that three independent variables related to individuals’ demographic features and political and foreign policy attitudes have shown variety among aspects. In this section, we discuss our findings in detail.

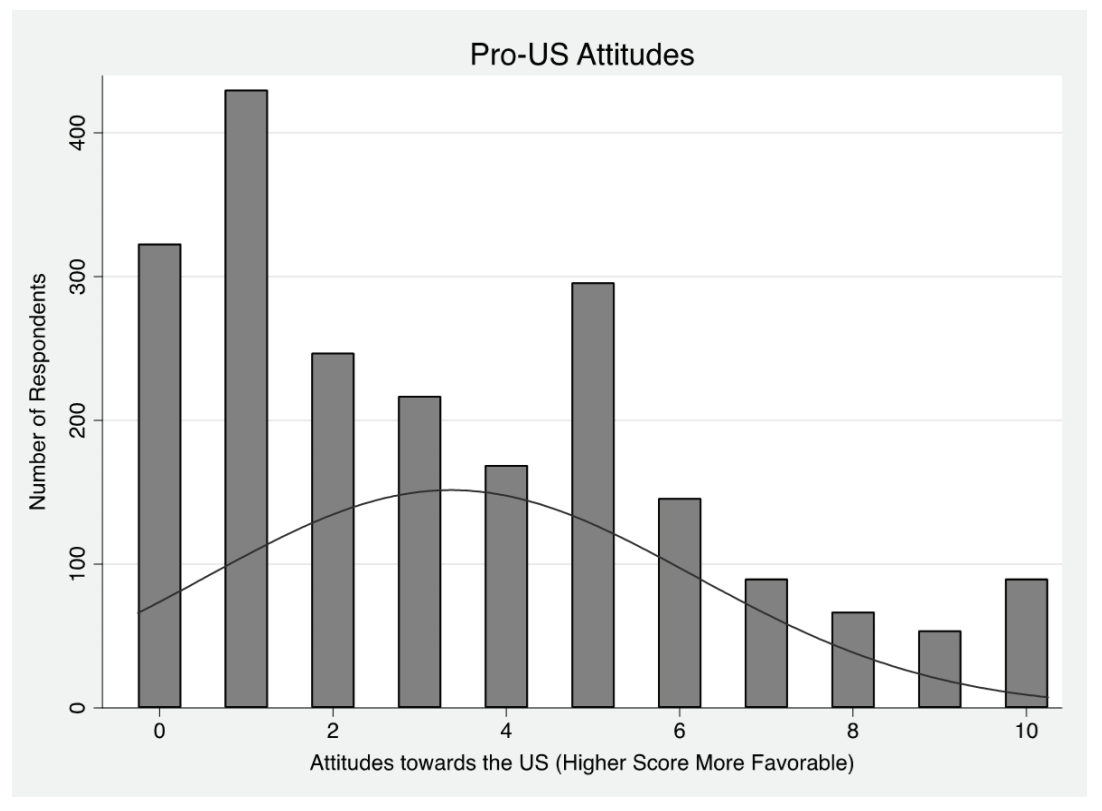

Figure 1. General Attitudes of Participants towards the US

To begin with a macro-analysis, Figure 1 provides a general picture of Turkish public opinion toward the US. The results indicate that the probability of exhibiting anti-American attitudes is high within the general perception of the population. As seen in Figure 1, while around 30% of respondents scored 1, 2 and 3, indicating a very negative attitude towards the US, more positive opinions were less common, with only around 8% of respondents giving scores of 8, 9 and 10. Yet, this picture alone cannot reveal the dimensionality regarding the sources of negative attitudes. Moreover, unlike negative attitudes, one should also explain what makes the US more favorable in the eyes of a relatively negative public opinion. Therefore, we require further analyses to understand why the Turkish public demonstrates positive opinions of the US.

Table 2. Pro-US Components

In Table 2, we present the results of an empirical model explaining the sources of positive attitudes towards the U.S employing a logistic regression model. We report the findings for each dependent variable in separate columns, namely the contribution of various dimensions towards positive attitudes towards the US. We focus on eight dependent variables, with each variable being estimated using a single model. This model incorporates demographic factors, political and foreign policy attitudes as variables. The results of this estimation are presented in Figures 2-8.

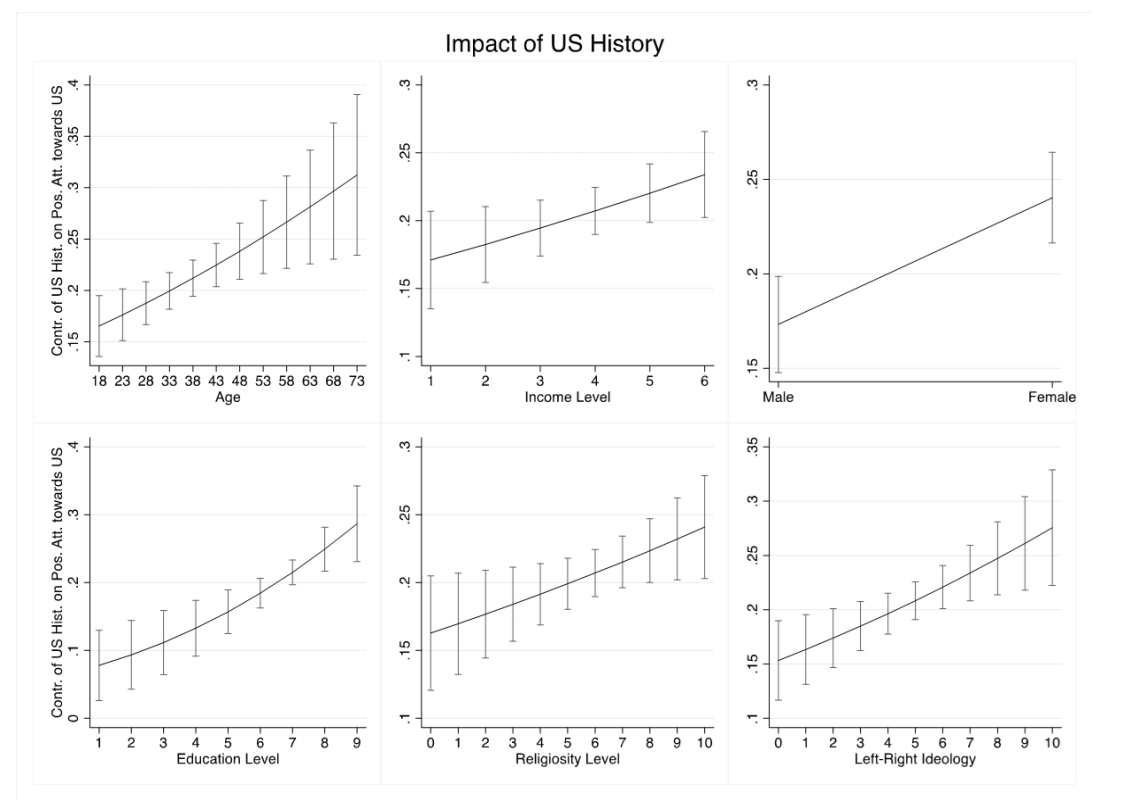

Figure 2. Impact of US History

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of US-Türkiye historical relations on individuals’ positive attitudes toward the US. The study revealed that factors such as individuals’ age, income, gender, education, voting interest, religious tendencies, ideological stance, and cosmopolitan ideas, influenced how they assess the role US-Türkiye historical relations play in their attitudes towards the US. The probability of expressing a positive attitude towards historical ties is notably high when participants’ age, income, education, and religious level increase. For example, the impact of US history on the probability of exhibiting a positive attitude towards the US increases from approximately 15% to 35% as the age of the participants increases. At the same time, as participants’ income and education levels increase, the impact size increases from approximately 15% to 25% for income levels and from around 10% to over 30% for education levels when the influence of historical relations is considered. Female participants are 25% more likely to show positive attitudes than men.

The religiosity variable indicates that individuals with a higher level of religiosity tend to hold more positive attitudes towards the US when the impact of historical ties between the two countries is considered. Specifically, 10% of those with the lowest level of religiosity display positive attitudes, while 30% of those with the highest level of religiosity display positive attitudes. Lastly, the ideological disposition revealed a clear trend. As one moves to the right on the ideological spectrum, the likelihood of individuals displaying positive attitudes increases; particularly, 35% of those on the far-right exhibit more positive attitudes in the influence of historical relations.

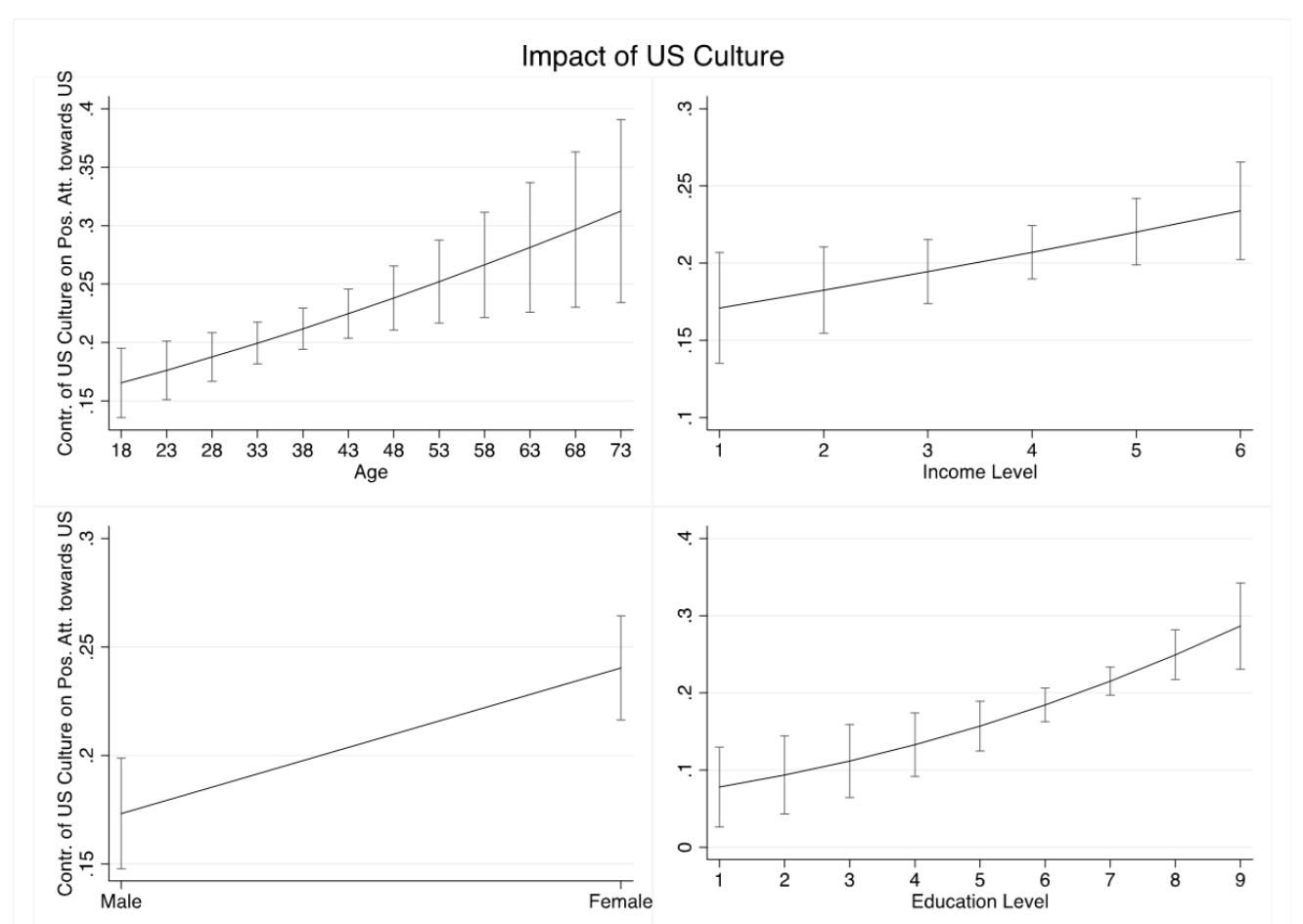

Figure 3. Impact of US Culture and Civilization

In Figure 3, we present the substantive findings regarding how individuals’ positive attitudes towards the US are influenced by American culture and civilization. The results indicate that such impact is conditioned on participants’ gender, income level, anti-government stances, ideological orientation, isolationist and cosmopolitan foreign policy attitudes. The predicted probability of American culture and civilization making a positive contribution towards attitudes about the US increases with the individuals’ income and anti-government stance. Also, female participants hold a more positive attitude towards the US in the context of American culture. Similar to historical relations, the likelihood of positive opinion is higher as one moves right in the ideological spectrum.

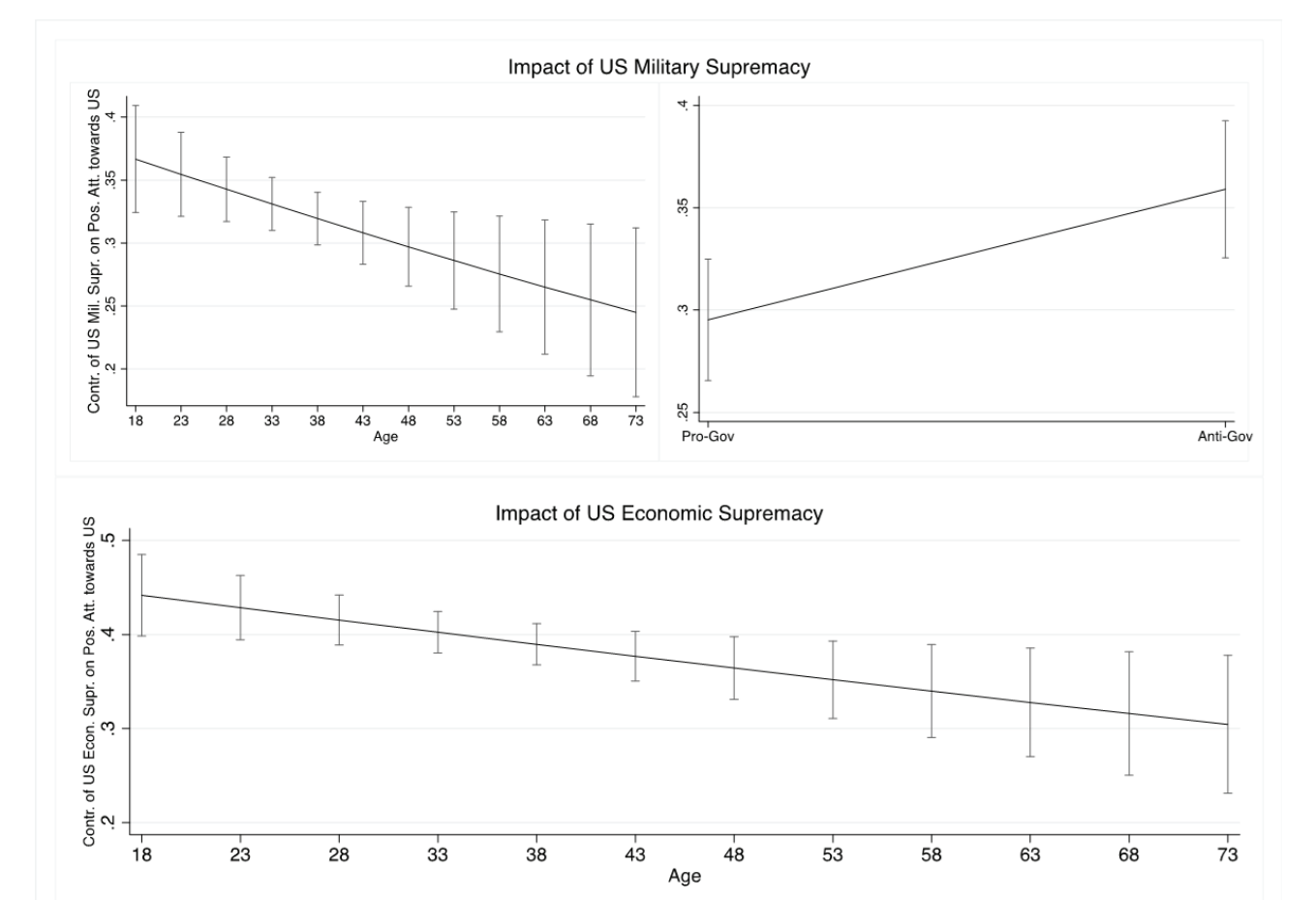

Figure 4a-b. Impact of US Military Supremacy and US Economic Supremacy

The effect of US military supremacy on individuals’ positive attitudes towards the US is conditional on individuals’ age, anti-government stance, isolationist and cosmopolitan tendencies. We report the substantive results in Figure 4a. The results here indicate that as individuals age, they tend to express more anti-American attitudes once US military’s perceived superiority is taken into account. For example, the predicted probability of expressing a positive attitude towards the US in the context of the country’s military supremacy is approximately 35% among the youngest participants, while this attitude decreases to approximately 15% among the oldest individuals. Also, individuals who hold opposing views of their government are more likely to hold a positive attitude towards the US under the influence of US military supremacy. The predicted probability of holding a positive attitude towards the US is around 40% among individuals with an anti-government stance compared to those with a pro-government stance.

Regarding the influence of US economic supremacy, our results indicate that individuals’ age, frequency of following the news, and isolationist behavior have statistically significant effects on their positive attitudes toward the US. Figure 4b shows that younger participants are more likely to hold a pro-American view considering US economic supremacy in the world. While the probability of holding a positive opinion is approximately 25% among the oldest participants, this number increases to around 45% for the younger group.

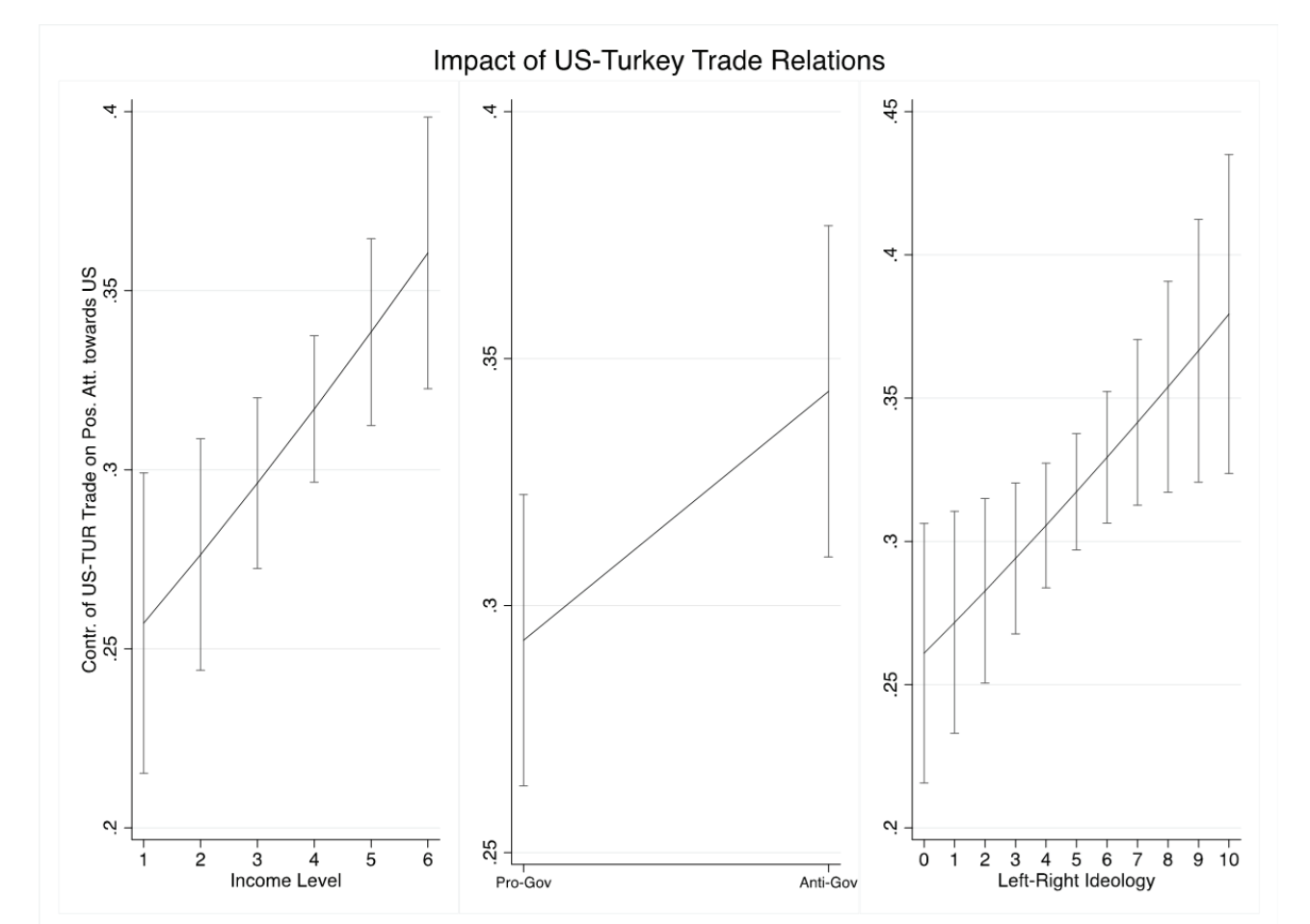

Figure 5. Impact of US-Türkiye Trade Relations

Next, we examine the impact of US -Türkiye trade relations on Turkish public opinion toward the US. Our results report that such impact is conditioned on individuals’ income level, interest in politics, anti-government stance, ideological positions, and cosmopolitan attitudes in foreign policy. In Figure 5, we present that the probability of showing a positive attitude toward the US under the influence of perceived US-Türkiye trade relations increases from approximately 25% to 35% with increasing income. Additionally, individuals with an anti- government stance in Türkiye are likely to exhibit a positive attitude towards the US up to 35%. This number decreases by 25% among those with a pro-government stance. The predicted probabilities of holding a negative attitude towards the US are higher among the left-wing participants. Those on the far left of the ideological spectrum have a probability of a positive attitude of about 25%, while those on the far right have a probability of approximately 45% when it comes to the impact of US-Türkiye trade relations.

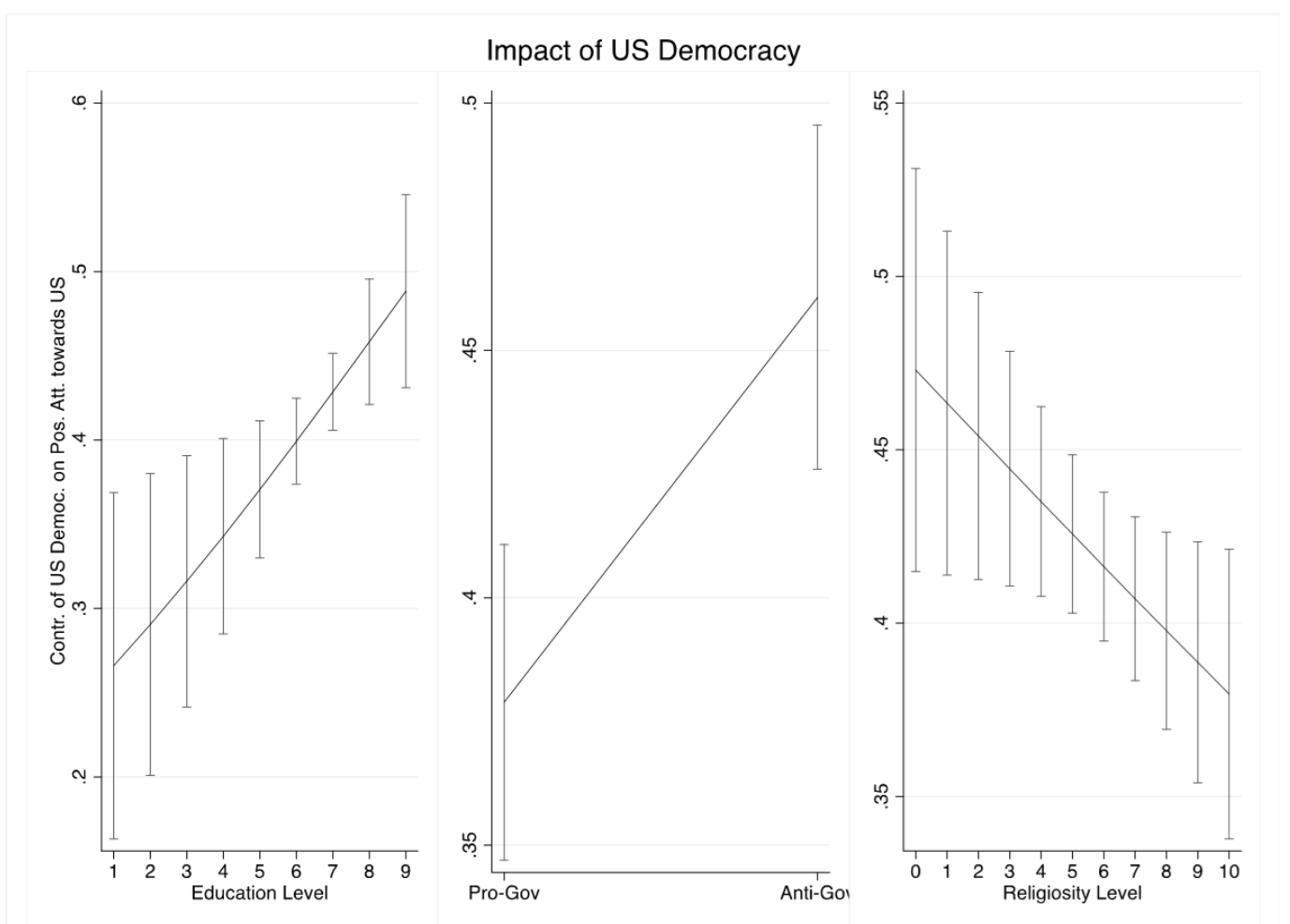

Figure 6. Impact of US Democracy

In Figure 6 we present that the impact of American democracy and the country’s political system on Turkish public perception of the US is conditioned on the level of education, anti-government sentiments, religiosity, and isolationist and cosmopolitan foreign policy attitudes. The predicted probability of a positive attitude is approximately 20% for individuals with the lowest education level, while it rises to around 50% for those with the highest education level. Opposite views of individuals towards their government also increase the likelihood of a positive attitude towards the US regarding perceived US democracy. Participants with anti-government stances are 45% more likely to express a positive attitude towards the US. Also, when individuals’ level of religiosity increases, the probability of holding a negative attitude towards the US increases when the impact of US democracy is considered. Those who identify themselves as least religious have a positive attitude probability of about 50%, while those who identify themselves as the most religious have a probability of approximately 35%.

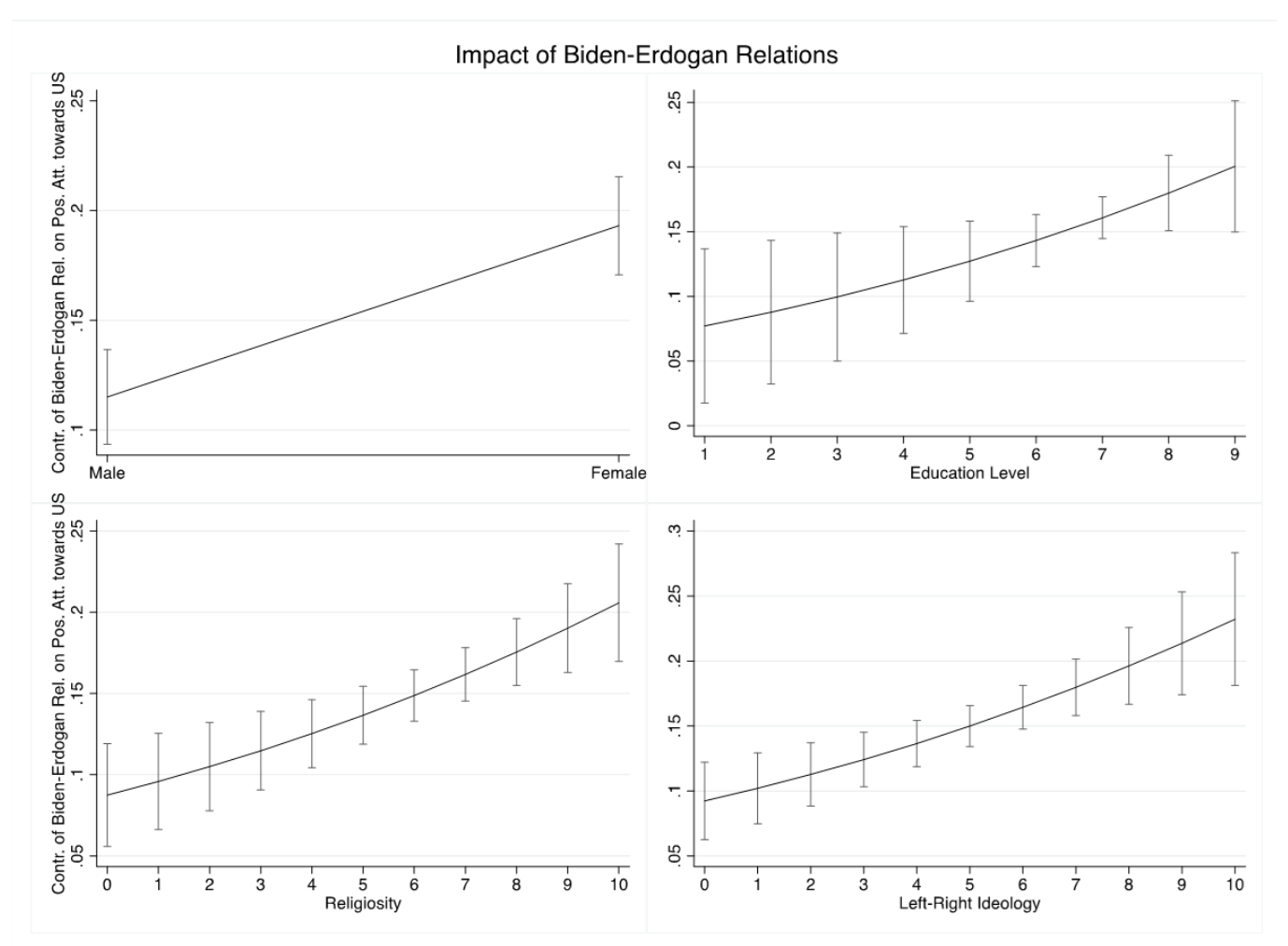

Figure 7. Impact of Biden – Erdoğan Relations

In the context of Biden-Erdoğan relations, we found that the gender, level of education, religiosity, ideological position, and cosmopolitan foreign policy attitudes of the participants were significant predictors of their attitudes towards the US. In Figure 7, we report that the predicted probability of holding a pro-American attitude increased when the level of education and the number of female participants increased. Furthermore, the level of religiosity and a right-wing ideological position also demonstrated a likelihood of a positive attitude under the influence of leader-to-leader relations. When the leader-to-leader relations are asked of the participants, females have around 20% probability of holding a positive attitude towards the US. In comparison, the likelihood of showing a positive attitude towards the US is around 10% among male participants. While the probability of showing a more positive view is about 10% at the lower education level, it increases to around 25% at the highest level. Also, at the level of religiosity, the probability of a positive attitude under the influence of Biden-Erdoğan relations dynamics ranges from approximately 10% for those with the lowest religiosity level to approximately 25% for those with the highest religiosity level. The ideological shift from left to right among participants also increased positive attitudes toward the US from 10% on the far left to about 25% on the far right.

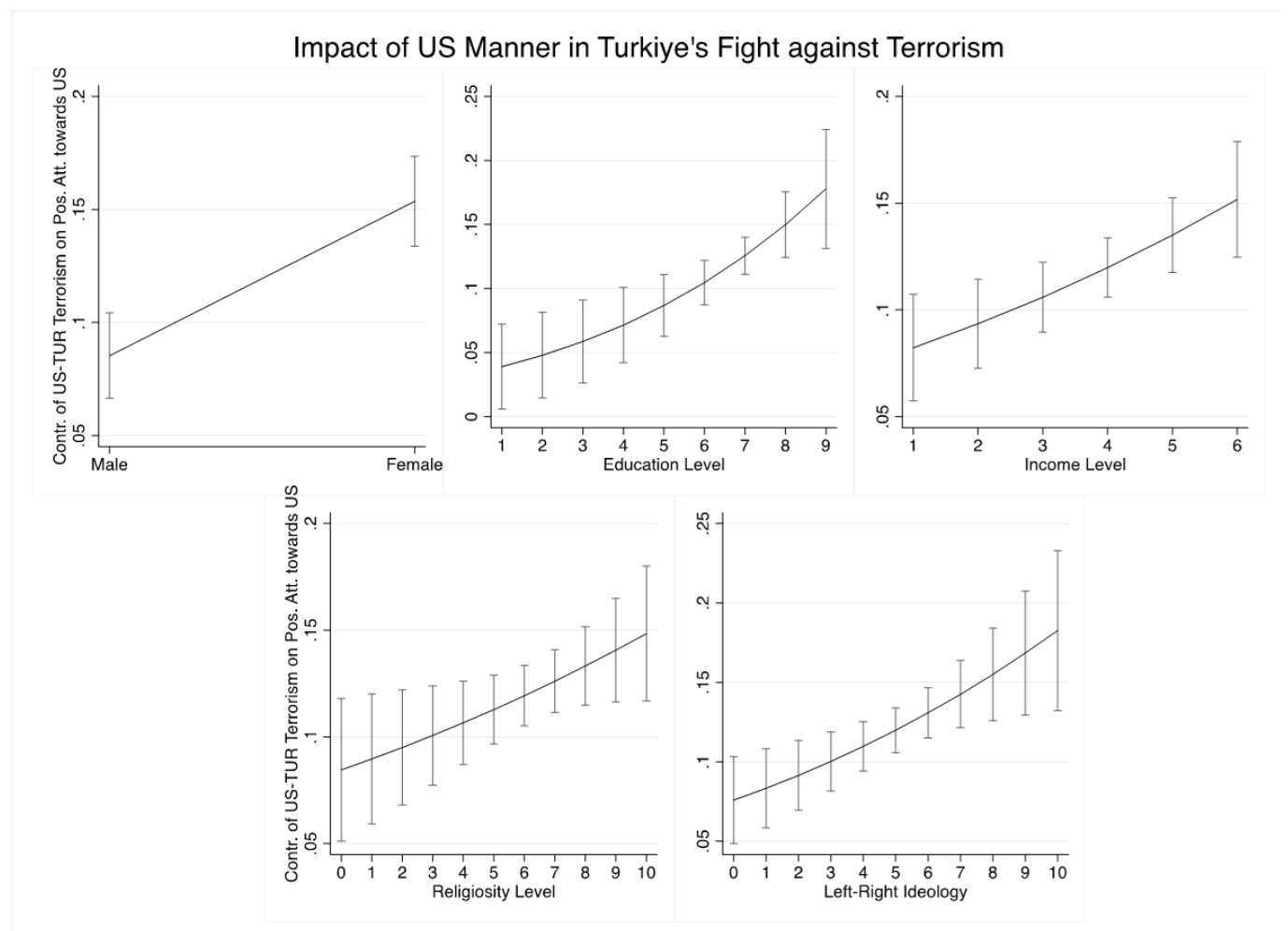

Figure 8. Impact of US Manner in Türkiye’s Fight against Terrorism

Lastly, in the context of the impact of the US position in Türkiye’s counter-terrorism efforts on individuals’ likelihood of positive opinion towards the US, we found that individuals’ gender, level of income and education, interest in polls, level of religiosity, ideological position, and cosmopolitanism, isolationist, and multilateralist attitudes in foreign policy are conditional on such influence.

For example, female respondents are more likely to hold a more positive view of the US than male respondents. Indeed, 20% of female participants expressed a positive opinion about the US when the US policy on Türkiye’s fight against the PKK was asked of them. This probability dropped below 10% for male respondents. When the level of income and education increase, the probability of expressing a positive attitude towards the US regarding the impact of US policy on PKK terrorism increases. Moreover, the predicted probability of individuals with the highest religiosity level expressing a positive attitude towards the US is approximately 20%. In comparison, those with the lowest religiosity level show a likelihood of approximately 5%. In the ideological spectrum, the likelihood of showing a positive view towards the US is around 20% among participants who identify themselves as far right. In contrast, the probability of left-wing participants holding a positive attitude is around 5%.

5. Conclusion

The literature on attitudes towards the US generally examines the demand side of public opinion. Scholars focus on anti-American attitudes to make sense of countries’ foreign policy objectives. However, we contend that individual attitudes towards the US are multifaceted and are affected by the US itself and its foreign policies. Thus, we attempted to answer the following question: What are the determinants of the variation in individuals’ attitudes towards the US in Türkiye? This question is essential to understand how the US produces divergent attitudes among different layers of the Turkish society. Also, it provides insights into Türkiye’s long-standing relationship with the US and its changing foreign policy dynamics by revealing the Turkish public’s dynamics.

Our empirical findings support our argument that focusing on the supply side of anti-Americanism in Türkiye is essential. In this study, our empirical model indicates that the eight dependent variables, which represent the US dimensions of Turkish public opinion, exert a significant influence on individuals, shaping their opinions in accordance with their demographic characteristics and political and foreign policy attitudes. Moreover, the findings also reveal that despite the general anti-American sentiment within the society, there is a great variation of causes, which policy-makers should take into account. Looking into the future, we believe that the next step could be to examine Turkish public opinion towards other major powers and especially the European Union, Russia and China. Investigating Turkish public opinion towards other great major powers could allow us to present a comparative dimension to explain why the same individuals have different or similar attitudes towards these countries. Adopting a comparative perspective can also lead us to test if individuals in Türkiye adopt a more structured and comprehensive perspective towards the US compared to other great powers. Moving beyond the Turkish case, our strategy also has implications for the formation of attitudes towards the US in other countries, especially those that have ongoing foreign policy crises with the US. Therefore, the argument can be tested in other contexts.

Finally, the article has implications for US public diplomacy in Türkiye as well as other countries. Most importantly, Washington should put higher effort into developing policies that aim to attract support from different segments of the society. While the US position on the YPG and the PKK will continue to negatively shape individual attitudes, the historical and economic dimension of the bilateral relationship can especially be highlighted by policymakers to improve the American image in the eyes of the Turkish public. The overall decline of US hegemony can be expected to shape different segments of the Turkish public differently. Still, our results indicate that the growing US military presence in Türkiye’s close neighborhood (i.e. Greece) will trigger concerns about Türkiye’s national security and sovereignty across different layers of the Turkish society. Similarly, the outcome of the upcoming US presidential elections is likely to have a conjunctural effect on the public opinion. Our results have a significant implication for Turkish policy makers as well. Because negative attitudes towards the US are common across different segments of the Turkish society, it is generally risk-free and even beneficial for Turkish politicians to develop an anti-American discourse. Still, it would be wrong to assume that such anti-American rhetoric would always work for domestic political purposes – contrarily, our results demonstrate that the Turkish public may demonstrate positive attitudes towards the US in various dimensions.

All in all, this article introduced a novel approach to understand the complex dynamics of the Turkish public opinion towards the US. While there are undoubtedly more factors at play in shaping public opinion towards the US and other major powers, this study opens a new avenue for future research by focusing on the effect of countries’ particular characteristics and policies on individuals.

Acknowledgements: We thank the participants of the “Continuities and Changes in Türkiye-US Relations” workshop, panels at the 2022 International Studies Association Convention in Nashville, USA and the 2024 International Relations Congress in Ordu, Türkiye as well as the editors and anonymous reviewers of All-Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace for their contributions and helpful comments. Seçkin Köstem and Efe Tokdemir acknowledge the support of TÜBA-GEBİP Award, and Efe Tokdemir acknowledges the support of TÜBİTAK Incentive Award. All errors are our own.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/RKZI7Y

Notes

(The authors are listed in reverse alphabetical order)

[i] Emre Erşen and Seçkin Köstem, “Introduction: Understanding the Dynamics of Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia,” in Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia: Geopolitics and Foreign Policy in a Changing World Order, eds. Emre Erşen and Seçkin Köstem (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), 2; Mustafa Kutlay and Ziya Öniş. “Turkish Foreign Policy in a Post-Western Order: Strategic Autonomy or New Forms of Dependence?” International Affairs 97, no. 4 (2021): 1086.[ii] “Türk Dış Politikası Kamuoyu Algısı Araştırması 2023,” Kadir Has University, 2023, accessed date April 10, 2024. https://www.khas.edu.tr/khas-kurumsal-arastirmalar/

[iii] See, Giulio Gallarotti and Isam Yahia Al-Filali, “Saudi Arabia’s Soft Power,” International Studies 49, no. 3-4 (2012): 233-261; Joseph S. Nye, “On the Rise and Fall of American Soft Power,” New Perspectives Quarterly 22, (2005): 75-79; Nicu Popescu, “Russia’s Soft Power Ambitions,” CEPS Policy Briefs, no. 115 (2006): 1-3; Andrei P. Tsygankov, “If Not by Tanks, Then by Banks? The Role of Soft Power in Putin’s Foreign Policy,” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 7 (2006): 1079-1099.

[iv] See, Giacomo Chiozza, Anti-Americanism and the American World Order (Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009) for an exception.

[v] Sarah S. Bush and Amaney A. Jamal, “Anti-Americanism, Authoritarian Politics, and Attitudes about Women’s Representation: Evidence from a Survey Experiment in Jordan,” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2015): 34-45; Daniel Corstange and Nikolay Marinov, “Taking Sides in Other People’s Elections: The Polarizing Effect of Foreign Intervention,” American Journal of Political Science 56, no. 3 (2012): 655-670; Benjamin E. Goldsmith and Yusaku Horiuchi, “In Search of Soft Power: Does Foreign Public Opinion Matter for US Foreign Policy?” World Politics 64, no. 3 (2012): 555-585.

[vi] Brendon O’Connor, “A Brief History of Anti-Americanism: From Cultural Criticism to Terrorism,” Australasian Journal of American Studies 23, no. 1 (2004): 78.

[vii] Giacomo Chiozza, “Disaggregating Anti-Americanism: An Analysis of Individual Attitudes toward the United States,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds. Robert O. Keohane and Peter J. Katzenstein (New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007), 93.

[viii] Alvin Z. Rubinstein and Donald E. Smith, “Anti-Americanism in the Third World,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 497, no. 1 (1988): 36.

[ix] Ibid., 45.

[x] Kenneth Minogue, “Anti-Americanism: A View from London,” The National Interest, no. 3 (1986): 43-49; Jean François Revel, “Contradictions of the Anti-Americanism Obsession,” New Perspectives Quarterly 20, (2003): 11-27; Russell A. Berman, Anti-Americanism in Europe: A Cultural Problem (California: Hoover Institute Press, 2004).

[xi] Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, “Varieties of Anti-Americanism: A Framework for Analysis,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds. Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007), 9-38; Sophie Meunier, “The Distinctiveness of French Anti-Americanism,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds. Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007), 129-157; Chiozza, Anti-Americanism.

[xii] Keohane and Katzenstein, “Introduction: Politics of Anti-Americanism,” 3.

[xiii] Meunier, “French Anti-Americanism,” 129.

[xiv] Chiozza, Anti-Americanism, 5.

[xv] Ole Rudolf Holsti, To See Ourselves as Others See Us: How Publics Abroad View the United States after 9/11 (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2009), 11.

[xvi] Narayan M. Datta, Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 8.

[xvii] Michael Mastanduno, “Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and US grand strategy after the Cold War,” International Security 21, no. 4 (1997): 58.

[xviii] Samuel P. Huntington, “The Lonely Superpower,” Foreign affairs 78, no. 2 (1999): 42.

[xix] Alastair I. Johnston and Daniela Stockmann, “Chinese Attitudes toward the United States and Americans,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds. Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007), 160; Efe Tokdemir, “‘You are not my type’: The Role of Identity in Evaluating Democracy and Human Rights Promotion,” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 24, no. 1 (2022): 74-94.

[xx] Fathali M. Moghaddam, “The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration,” American Psychologist 60, no. 2 (2005): 162.

[xxi] Abdel M. Abdallah, “Causes of Anti-Americanism in the Arab World: A Socio-Political Perspective,” Middle East 7, no. 4 (2003): 63; Marc Lynch, “Anti-Americanism in the Arab World,” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, eds. Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007), 196-224; Fawaz A. Gerges, The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Lars Berger, “Foreign Policies or Culture: What Shapes Muslim Public Opinion on Political Violence against the United States?” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 6 (2014): 782-796.

[xxii] Abdallah, “Causes of Anti-Americanism,” 196; Andrew L. Hammond, What the Arabs Think of America (Oxford: Greenwood World Publishing, 2007); Kylie Baxter and Shahram Akbarzadeh, US Foreign Policy in the Middle East: The Roots of Anti-Americanism (London: Routledge, 2008).

[xxiii] Lisa Blaydes and Drew A. Linzer, “Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism in the Islamic World,” American Political Science Review 106, no. 2 (2012): 227.

[xxiv] Peter A. Furia and Russell E. Lucas, “Arab Muslim Attitudes toward the West: Cultural, Social, and Political Explanations,” International Interactions 34, no. 2 (2008): 191.

[xxv] Paulo Z. Messitte, “The Politics of Anti-Americanism in France, Greece, and Italy,” PhD diss., (New York University, 2004), 2.

[xxvi] Blaydes and Linzer, “Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism,” 230.

[xxvii] Dinorah Azpuru and Dexter Boniface, “Individual-level Determinants of Anti-Americanism in Contemporary Latin America,” Latin American Research Review 50, no. 3 (2015): 112.

[xxviii] Efe Tokdemir, “Winning Hearts and Minds (!) The Dilemma of Foreign Aid in Anti-Americanism,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 6 (2017): 819-832.

[xxix] Corstange and Marinov, “Taking Sides in Other People’s Elections,” 656.

[xxx] Bush and Jamal, “Anti-Americanism, Authoritarian Politics, and Attitudes about Women’s Representation,” 35.

[xxxi] For a discussion of US-based exchange programs on liberalism and democracy in authoritarian countries, see Carol Atkinson, “Does Soft Power matter? A Comparative Analysis of Student Exchange Programs 1980–2006,” Foreign Policy Analysis 6, no.1 (2010): 2.

[xxxii] Robert K. Fleck and Christopher Kilby, “Changing aid regimes? US Foreign Aid from the Cold War to the War on Terror,” Journal of Development Economics 91, no. 2 (2010): 186.

[xxxiii] Michael A. Allen et al., “Outside the Wire: US Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States,” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 327.

[xxxiv] Tokdemir, “Winning hearts and minds (!),” 819-820.

[xxxv] Aylin Güney, “Anti-Americanism in Turkey: Past and Present,” Middle Eastern Studies 44, no. 3 (2008): 472; Ömer Taşpınar, “The Anatomy of Anti-Americanism in Turkey,” Insight Turkey 7, no. 2 (2005): 83; Efe Tokdemir, “Feels like Home: Effect of Transnational Identities on Attitudes towards Foreign Countries,” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 5 (2021): 1034-1048.

[xxxvi] Özgehan Şenyuva and Mustafa Aydın, “Turkish Public Opinion and Transatlantic Relations,” in Turkey’s Changing Transatlantic Relations, eds. Eda Kuşku Sönmez and Çiğdem Üstün (London: Lexington Books. 2021), 265-282.

[xxxvii] Güney, Anti-Americanism in Turkey, 472.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 475.

[xxxix] Ibid., 477.

[xl] Sellers G. Harris, Troubled Alliance: Turkish-American Problems in Historical Perspective, 1945-1971 - Vol. 2 (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1972), 125.

[xli] Nur Bilge-Criss, “A Short History of Anti-Americanism and Terrorism: The Turkish Case,” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 472-484: Nur Bilge-Criss, “Mercenaries of Ideology: Turkey’s Terrorism War,” in Terrorism and Politics, ed. Barry Rubin (London: Palgrave Macmillan. 1991), 127.

[xlii] Criss, “A Short History of Anti-Americanism,” 472-484.

[xliii] Füsun Türkmen, “Anti‐Americanism as a Default Ideology of Opposition: Turkey as a Case Study,” Turkish Studies 11, no. 3 (2010): 342.

[xliv] Ioannis N. Grigoriadis and Ümit Erol Aras, “Distrusted Partnership: Unpacking Anti‐Americanism in Turkey,” Middle East Policy 30, no. 1 (2023): 122-136.

[xlv] “What the World Thinks in 2002,” PEW Research Center, 2003, accessed date April 12, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2002/12/04/what-the-world-thinks-in-2002/

[xlvi] Richard Outzen, “Costly Incrementalism: US PKK Policy and Relations with Türkiye,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 0, no. 0 (2024): 1-22.

[xlvii] Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas, Türkiye, the PKK, and U.S. Involvement: A Chronology (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2019), accessed date 21 April, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11380

[xlviii] Cem Birol, “Contractual Origins of Anti-Americanism: Pew 2013 Results,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 13, no. 2 (2024): 215-235; Seçkin Köstem, “Russian-Turkish Cooperation in Syria: Geopolitical Alignment with Limits,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 34, no. 6 (2023): 795-817.

[xlix] “Türk Dış Politikası Kamuoyu Algısı Araştırması 2023.”

[l] Giray Sadık, American Image in Turkey: US Foreign Policy Dimensions (Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009), 81.

[li] “Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act of August 2017,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 2, 2017, accessed date 29 August 2024. https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/countering-americas-adversaries-through-sanctions-act-related-sanctions

[lii] “Republic of Türkiye,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2023, accessed date August 29, 2024. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/turkey

[liii] Galip Dalay, “US-Turkey Relations will Remain Crisis-Ridden for a Long Time to Come,” Brookings, January 29, 2021, accessed date April 18, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-turkey-relations-will-remain-crisis-ridden-for-a-long-time-to-come/

[liv] Juan Cole, “Anti-Americanism: It’s the Policies,” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1121.

Bibliography

Abdallah, Abdel M. “Causes of Anti-Americanism in the Arab World: A Socio-Political Perspective.” Middle East 7, no. 4 (2003): 62-73.

Allen, Michael A., et al., “Outside the Wire: US Military Deployments and Public Opinion in Host States.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 326-341.

Atkinson, Carol. “Does Soft Power matter? A Comparative Analysis of Student Exchange Programs 1980–2006.” Foreign Policy Analysis 6, no. 1 (2010): 1-22.

Azpuru, Dinorah, and Dexter Boniface. “Individual-level Determinants of Anti-Americanism in Contemporary Latin America,” Latin American Research Review 50, no. 3 (2015): 111-134.

Baxter, Kylie, and Shahram Akbarzadeh. US Foreign Policy in the Middle East: The Roots of Anti-Americanism. London: Routledge, 2008.

Berger, Lars. “Foreign Policies or Culture: What Shapes Muslim Public Opinion on Political Violence against the United States?” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 6 (2014): 782-796.

Berman, Russell A. Anti-Americanism in Europe: A Cultural Problem. California: Hoover Institute Press, 2004.

Bilge-Criss, Nur. “A Short History of Anti-Americanism and Terrorism: The Turkish Case.” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 472-484.

——. “Mercenaries of Ideology: Turkey’s Terrorism War.” In Terrorism and Politics, edited by Barry Rubin, 123-150. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 1991.

Birol, Cem. “Contractual Origins of Anti-Americanism: Pew 2013 Results.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 13, no. 2 (2024): 215-235.

Blaydes, Lisa, and Drew A. Linzer. “Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism in the Islamic World.” American Political Science Review 106, no. 2 (2012): 225-243.

Bush, Sarah S., and Amaney A. Jamal. “Anti-Americanism, Authoritarian Politics, and Attitudes about Women’s Representation: Evidence from a Survey Experiment in Jordan.” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2015): 34-45.

Chiozza, Giacomo. “Disaggregating Anti-Americanism: An Analysis of Individual Attitudes toward the United States.” In Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Robert O. Keohane and Peter J. Katzenstein, 93-128. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

——. Anti-Americanism and the American World Order. Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Cole, Juan. “Anti-Americanism: It’s the Policies.” The American Historical Review 111, no. 4 (2006): 1120-1129.

Corstange, Daniel, and Nikolay Marinov. “Taking Sides in Other People’s Elections: The Polarizing Effect of Foreign Intervention.” American Journal of Political Science 56, no. 3 (2012): 655-670.

“Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act of August 2017.” U.S. Department of the Treasury. August 2, 2017. Accessed date 29 August 2024. https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/countering-americas-adversaries-through-sanctions-act-related-sanctions

Dalay, Galip. “US-Turkey Relations will Remain Crisis-Ridden for a Long Time to Come.” Brookings. January 29, 2021. Accessed date April 18, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-turkey-relations-will-remain-crisis-ridden-for-a-long-time-to-come/

Datta, Narayan M. Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Erşen, Emre, and Seçkin Köstem. “Introduction: Understanding the Dynamics of Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia.” In Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia: Geopolitics and Foreign Policy in a Changing World Order, edited by Emre Erşen and Seçkin Köstem, 1-14. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

Fleck, Robert K., and Christopher Kilby. “Changing Aid Regimes? US Foreign Aid from the Cold War to the War on Terror.” Journal of Development Economics 91, no. 2 (2010): 186.

Furia, Peter A., and Russell E. Lucas. “Arab Muslim Attitudes toward the West: Cultural, Social, and Political Explanations.” International Interactions 34, no. 2 (2008): 186-207.

Gallarotti, Giulio, and Isam Yahia Al-Filali. “Saudi Arabia’s Soft Power.” International Studies 49, no. 3-4 (2012): 233-261.

Gerges, Fawaz A. The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Goldsmith, Benjamin E., and Yusaku Horiuchi. “In Search of Soft Power: Does Foreign Public Opinion Matter for US Foreign Policy?” World Politics 64, no. 3 (2012): 555-585.

Grigoriadis, Ioannis N., and Ümit Erol Aras. “Distrusted Partnership: Unpacking Anti‐Americanism in Turkey.” Middle East Policy 30, no. 1 (2023): 122-136.

Güney, Aylin. “Anti-Americanism in Turkey: Past and Present.” Middle Eastern Studies 44, no. 3 (2008): 471-487.

Hammond, Andrew L. What the Arabs Think of America. Oxford: Greenwood World Publishing, 2007.

Harris, Sellers G. Troubled Alliance: Turkish-American Problems in Historical Perspective, 1945-1971 - Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1972.

Holsti, Ole Rudolf. To See Ourselves as Others See Us: How Publics Abroad View the United States after 9/11. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Huntington, Samuel P. “The Lonely Superpower.” Foreign affairs 78, no. 2 (1999): 35-49.

Johnston, Alastair I., and Daniela Stockmann. “Chinese Attitudes toward the United States and Americans.” In Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, 157-195. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and Robert O. Keohane. Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

——. “Varieties of Anti-Americanism: A Framework for Analysis.” In Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, 9-38. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Köstem, Seçkin. “Russian-Turkish Cooperation in Syria: Geopolitical Alignment with Limits.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 34, no. 6 (2023): 795-817.

Kutlay, Mustafa, and Ziya Öniş. “Turkish Foreign Policy in a Post-Western Order: Strategic Autonomy or New Forms of Dependence?” International Affairs 97, no. 4 (2021): 1085-1104.

Lynch, Marc. “Anti-Americanism in the Arab World.” in Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, 196-224. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Mastanduno, Michael. “Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and US grand strategy after the Cold War.” International Security 21, no. 4 (1997): 49-88.

Messitte, Paulo Z. “The Politics of Anti-Americanism in France, Greece, and Italy.” PhD dissertation. New York University, 2004.

Meunier, Sophie. “The Distinctiveness of French Anti-Americanism.” In Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane, 129-157. New Jersey: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Minogue, Kenneth. “Anti-Americanism: A View from London.” The National Interest, no. 3 (1986): 43-49.

Moghaddam, Fathali M. “The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration.” American Psychologist 60, no. 2 (2005): 161-169.

Nye, Joseph S. “On the Rise and Fall of American Soft Power.” New Perspectives Quarterly 22, (2005): 75-79.

O’Connor, Brendon. “A Brief History of Anti-Americanism: From Cultural Criticism to Terrorism.” Australasian Journal of American Studies 23, no. 1 (2004): 77-92.

Outzen, Richard. “Costly Incrementalism: US PKK Policy and Relations with Türkiye.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 0, no. 0 (2024): 1-22.

Popescu, Nicu. “Russia’s Soft Power Ambitions.” CEPS Policy Briefs, no. 115 (2006): 1-3.

“Republic of Türkiye.” Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2023. Accessed date August 29, 2024. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/turkey

Revel, Jean François. “Contradictions of the Anti-Americanism Obsession.” New Perspectives Quarterly 20, (2003): 11-27.

Rubinstein, Alvin Z., and Donald E. Smith. “Anti-Americanism in the Third World.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 497, no. 1 (1988): 35-45.

Sadık, Giray. American Image in Turkey: US Foreign Policy Dimensions. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009.

Şenyuva, Özgehan, and Mustafa Aydın. “Turkish Public Opinion and Transatlantic Relations.” In Turkey’s Changing Transatlantic Relations, edited by Eda Kuşku Sönmez and Çiğdem Üstün, 265-282. London: Lexington Books. 2021.

Taşpınar, Ömer. “The Anatomy of Anti-Americanism in Turkey.” Insight Turkey 7, no. 2 (2005): 83-98.

Tokdemir, Efe. “‘You are not my type’: The Role of Identity in Evaluating Democracy and Human Rights Promotion.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 24, no. 1 (2022): 74-94.

——. “Feels like Home: Effect of Transnational Identities on Attitudes towards Foreign Countries.” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 5 (2021): 1034-1048.

——. “Winning Hearts and Minds (!) The Dilemma of Foreign Aid in Anti-Americanism.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 6 (2017): 819-832.

Tsygankov, Andrei P. “If Not by Tanks, Then by Banks? The Role of Soft Power in Putin’s Foreign Policy.” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 7 (2006): 1079-1099.

“Türk Dış Politikası Kamuoyu Algısı Araştırması 2023.” Kadir Has University. 2023. Accessed date April 10, 2024. https://www.khas.edu.tr/khas-kurumsal-arastirmalar/

Türkmen, Füsun. “Anti‐Americanism as a Default Ideology of Opposition: Turkey as a Case Study.” Turkish Studies 11, no. 3 (2010): 329-345.

“What the World Thinks in 2002.” PEW Research Center. 2003. Accessed date April 12, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2002/12/04/what-the-world-thinks-in-2002/

Zanotti, Jim, and Clayton Thomas. Türkiye, the PKK, and U.S. Involvement: A Chronology. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2019. Accessed date 21 April, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11380